Stanmore

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "a small town in Middlesex, about nine miles northwest of the city center. It is now part of greater London but was a rural area in the 1890s."

GANGNES: about 3 miles west of Edgware

Stanmore

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "a small town in Middlesex, about nine miles northwest of the city center. It is now part of greater London but was a rural area in the 1890s."

GANGNES: about 3 miles west of Edgware

Pinner

GANGNES: village about 3.5 miles west of Stanmore

New Barnet

GANGNES: village about 5 miles northeast of Edgware

“What is that murmur?” asked the stouter woman suddenly. They all listened and heard a sound like the droning of wheels in a distant factory, a murmurous sound, rising and falling. “If one did not know this was Middlesex,” said my brother, “we might take that for the sound of the sea.” “Do you think George can possibly find us here?” asked the slender woman abruptly. The man’s wife was for returning to their house, but my brother urged a hundred

GANGNES: This text was cut, with the rest of the last sentence, from the 1898 volume, and replaced with a few new sentences that streamline the scene. See text comparison page.

“That sound,”

GANGNES: The next two paragraphs are cut from the 1898 volume, with smaller sentences and fragments added and cut through the end of page 355. Again Wells takes great care over the flow of this scene. See text comparison page.

North Road

GANGNES: a road that runs directly north from Barnet Road, leading out of Barnet and far to the north

There were sad, haggard women rushing by, well dressed, with children that cried and stumbled, their dainty clothes smothered in dust, their weary faces smeared with tears. With many of those came men, sometimes helpful, sometimes lowering and savage. Fighting side by side with them pushed some weary street outcast in faded black rags, wide-eyed, loud-voiced, and foul-mouthed. There were sturdy workmen thrusting their way along, wretched unkempt men clothed like clerks or shopmen, struggling spasmodically, a wounded soldier my brother noticed, men dressed in the clothes of railway porters, one wretched creature in a nightshirt with a coat thrown over it.

GANGNES: In the 1898 volume, this section is moved down and inserted before "But varied as its composition was..." See text comparison page.

“What does it all mean?” whispered Miss Elphinstone. “I don’t know,” said my brother. “But this poor child is dropping with fear and fatigue.”

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

Chief Justice

GANGNES: Note that MCCONNELL disagrees with HUGHES AND GEDULD and STOVER here about the importance of this title.

From MCCONNELL 220: "In England, the presiding judge of any court with several members."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 215: "The nearest American equivalent [of "Chief Justice" here] (although there are many differences in the two offices) would be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court."

From STOVER: "The Lord Chief Justice of England is equivalent to the Chief Justice of the United States."

sovereigns

From MCCONNELL 220: gold coins worth two pounds, eighteen shillings (each)

From DANAHAY 124: gold coins worth two pounds each ("the man has a lot of heavy money in his bag")

GANGNES: Note that MCCONNELL's and DANAHAY's respective accounts of a sovereign's worth are not the same as one another or as HUGHES AND GEDULD's (and STOVER's) below.

his limbs lay limp and dead

GANGNES: The 1898 volume changes this to "his lower limbs lay limp and dead"; this clarifies why the man is able to grasp for his money even though his back is broken. See text comparison page.

gold

From HUGHES AND GEDULD: "refers to sovereigns: gold coins worth one English pound each."

GANGNES: Note that HUGHES AND GEDULD's account of a sovereign's worth is not the same as MCCONNELL's or DANAHAY's above. STOVER (157) agrees with HUGHES AND GEDULD.

As they passed the bend in the lane

GANGNES: From this point through the end of the installment, very significant changes were made between the serialized version and the 1898 volume. Apart from a large cut (see below), the final four large paragraphs were moved to the beginning of the next chapter (XVII). This difference changes the narrative's pacing and moments of suspense. See text comparison page.

So my brother describes one striking phase of the great flight out of London on the morning of Monday. So vividly did that scene at the corner of the lane impress him, so vividly did he describe it, that I can now see the details of it almost as distinctly as if I had been present at the time. I wish I had the skill to give the reader the effect of his description. And that was just one drop of the flow of the panic taken and magnified.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume; perhaps it was thought to be redundant, especially with the change in chapter division. See note above and text comparison page.

Waltham Abbey

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 234: "a small town on the river Lea, in southwest Essex, bordering Epping Forest. In the 1890s there was an old gunpowder factory in the area."

GANGNES: about 15 miles to the east and slightly north of Edgware

Southend and Shoeburyness

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "Fully named Southend-on-Sea. A resort town in southeast Essex at the mouth of the Thames, thirty-three miles east of central London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "Shoebury or Shoeburyness [is] a coastal town at the mouth of the Thames, just east of Southend and thirty-eight miles east of London."

GANGNES: Southend is about 45 miles directly east of Edgware; Shoeburyness is just slightly east of that along the coast.

Deal and Broadstairs

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: Deal is "a resort town in Eastern Kent, about seven miles from Dover and sixty-eight miles east-southeast of central London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: Broadstairs is "a coastal town in northeast Kent, on the English Channel, about seventy miles east-southeast of central London."

GANGNES: Deal is slightly south of Broadstairs.

powder

GANGNES: gunpowder for cannons and other artillery

cut every telegraph

GANGNES: which is to say, cut the telegraph wires to make distance communication impossible

Installment 5 of 9 (August 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book I ("The Coming of the Martians"), Chapter XIV and part of XV of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions.

This is the cover of the August 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine:

That was how the Sunday Sun put it, and a clever, and remarkably prompt “hand-book” article in the Referee

From MCCONNELL 193: "Two evening papers. The Sun was published 1893-1906, the Referee 1877-1928.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 212: "The Sun, London's first popular halfpenny evening newspaper, was established in 1893 by T. P. O'Connor. A former London weekly, the Referee (founded 1877), was popular for its focus on humor, satire, sports, and theater."

GANGNES: The Referee was a "Sunday sporting newspaper"; the Sun was a Tory newspaper.

Source:

Putney

GANGNES: village/area on the south bank of the Thames on the way from Woking toward central London; about three-quarters of the way there

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 232: "a district of London located immediately south of the Thames, about seven miles west of the city center"

Molesey

GANGNES: village on the south bank of the Thames on the way from Woking to central London, beyond Weybridge and Walton but not quite as far as Kingston

Clock Tower and the Houses of Parliament

GANGNES: The Houses of Parliament are on the north bank of the Thames in Westminster, between Westminster Abbey and Westminster Bridge. The "Clock Tower" here is commonly referred to today as "Big Ben."

Fleet Street

GANGNES: Fleet Street is a central London road on the north side of the Thames; it becomes (the) Strand (see below) to the west. During the Victorian period it was the home of most major London periodical publishers. It is associated with the story of Sweeney Todd: the "Demon Barber of Fleet Street," who appeared in the Victorian "penny dreadful" The String of Pearls: A Romance (1846-7).

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: Fleet Street is "a famous central London thoroughfare linking Ludgate Circus and The Strand. Until 1988 it was the home of many of London's most important newspapers. During Wells's lifetime 'Fleet Street' was a term synonymous with the British press."

More information:

still wet newspapers

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 213: "This is a slip. Until about 1870, paper was dampened to ensure a good printing impression and was then dried, but by the 1890s dry paper was used.... The anachronism disappears in the Heinemann edition (p. 127), which reads: 'type, so fresh that the paper was still wet.'"

GANGNES: It is unclear what HUGHES AND GEDULD mean when they write that the "anachronism disappears in the Heinemann edition"; the Heinemann edition also includes this line on page 124.

no time to add a word of comment

GANGNES: The newspaper editors were so eager to get the newspapers printed and sell them that they did not include any journalistic commentary or other textual commentary on the proclamation; they simply reprinted it.

how ruthlessly the other contents of the paper had been hacked and taken out, to give this place

GANGNES: The other content they would have expected this newspaper to usually contain was left out so that it could accommodate the entire proclamation in large letters.

hastily fastening maps of Surrey to the glass

GANGNES: The shopkeeper is displaying maps of Surrey in his store window because that is the region in which the Martian invasion is taking place (Woking and its surrounding villages are in Surrey). He likely hopes that advertising the map in his window will prompt customers to buy maps of Surrey from him so they can follow the action.

Trafalgar Square

GANGNES: A famous square/plaza in central London, situated just to the south of the National Gallery. It features an iconic tower surrounded by four large lions. See the City of London's official page on the Square.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 234: "Central London's most famous concourse, dedicated to England's naval hero, Lord Nelson (and his victory at Trafalgar in 1805). In the center of the square there is a granite column, 145 feet tall, crowned with a statue of Nelson."

Sutton High Street on a Derby Day

GANGNES: The 1898 edition changes "Sutton" to "Epsom."

From MCCONNELL 198: "The town of Epsom, south of London, is the annual site of the Derby."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 213: "teeming with people"; see Frith's painting "Derby Day" (1856-58) (below)

Westminster to his apartments near Regent’s Park

GANGNES: Regent's Park is a large public park in the northern part of central London. It lies north of the Thames, and it would likely take the narrator's brother a little under an hour to walk there from the south, depending on where in Westminster he is and where his apartment is situated. Wells's final home was near Regent's Park.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 232: Regent's Park is "central London's largest park, containing the London Zoo and the Botanical Gardens. It extends north from Marylebone Road to Primrose Hill; and west from Albany to Grand Union Canal."

small hours

GANGNES: early hours after midnight ("wee hours")

stupid

GANGNES: In this case, not unintelligent, but rather, unaware or unknowing.

poisonous vapour

From DANAHAY 107: "Wells's vision of the use of poison gas, which was used as a weapon for the first time in World War I."

GANGNES: Some illustrations of The War of the Worlds created during and soon after the First World War distinguish themselves by focusing on the black smoke instead of the heat ray. One such illustration is the book cover for a Danish edition published in 1941. Considered in the light of weapons used during the First and Second World Wars, images such as this one become particularly haunting.

at Staines, Hounslow, Ditton, Esher, Ockham

GANGNES: These villages are all to the north or east of Woking and would be suitably arranged to face the crescent of Martian fighting machines.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: Hounslow is "a suburban area of Middlesex, about ten miles west of central London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 231: Ockham is "a village in Surrey, about two and a half miles southeast of Woking and five miles northwest of Guildford."

make a greater Moscow

GANGNES: MCCONNELL and HUGHES AND GEDULD seem to be at odds here about the historical significance of this reference. STOVER (147) agrees with HUGHES AND GEDULD.

From MCCONNELL 206: "From September 2 to October 7, 1812, the French Army of Napoleon occupied Moscow, burning and destroying more than three-fourths of the city. They were finally compelled to retreat, however, due to Russian guerrilla resistance and the impossibility of acquiring adequate provisions."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 213: "To frustrate the Martians by destroying their major objective, London, as the Russians did to Napoleon in 1812 by setting fire to Moscow."

Ditton and Esher

GANGNES: villages to the northeast of Woking on the south bank of the Thames, roughly between Walton and Kingston

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: Ditton is "a small town in central Kent, about four miles northwest of Maidstone."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: Esher is "a small town in northeast Surrey, fifteen miles southwest of London."

earthly artillery

GANGNES: HUGHES AND GEDULD (213) observe that this is likely a reference to Satan's "infernal artillery" in Milton's Paradise Lost, rather than a "celestial artillery" (STOVER 148 uses this term as well) as an inverse of "earthly artillery." In the context of a Martian invasion, however, "celestial" in opposition to "infernal" becomes complicated; in a narrative like Milton's, it would refer to Heaven, whereas in the context of Wells, it would be "the heavens," i.e., space. The Martians are far from benevolent angels; they are, perhaps, "avenging angels," or akin to infernal beings, despite being from a neighboring planet. In the context of this novel, might we imagine a new kind of artillery: an "alien artillery"?

(To be continued next month.)

GANGNES: In the serialized version of the novel, Chapter V was divided in half between installments 5 and 6. This imposed a kind of "false cliffhanger" that was often seen in Victorian serialized fiction because periodicals had a set number of pages per issue (sometimes with a little wiggle room) to devote to an installment of a serialized work.

This "false cliffhanger" would have affected a Victorian reader's sense of pacing and the feeling of suspense caused by the abrupt end of the installment in the middle of an intense battle. This a "to be continued" moment that was created by serialization rather than an author's intended pacing.

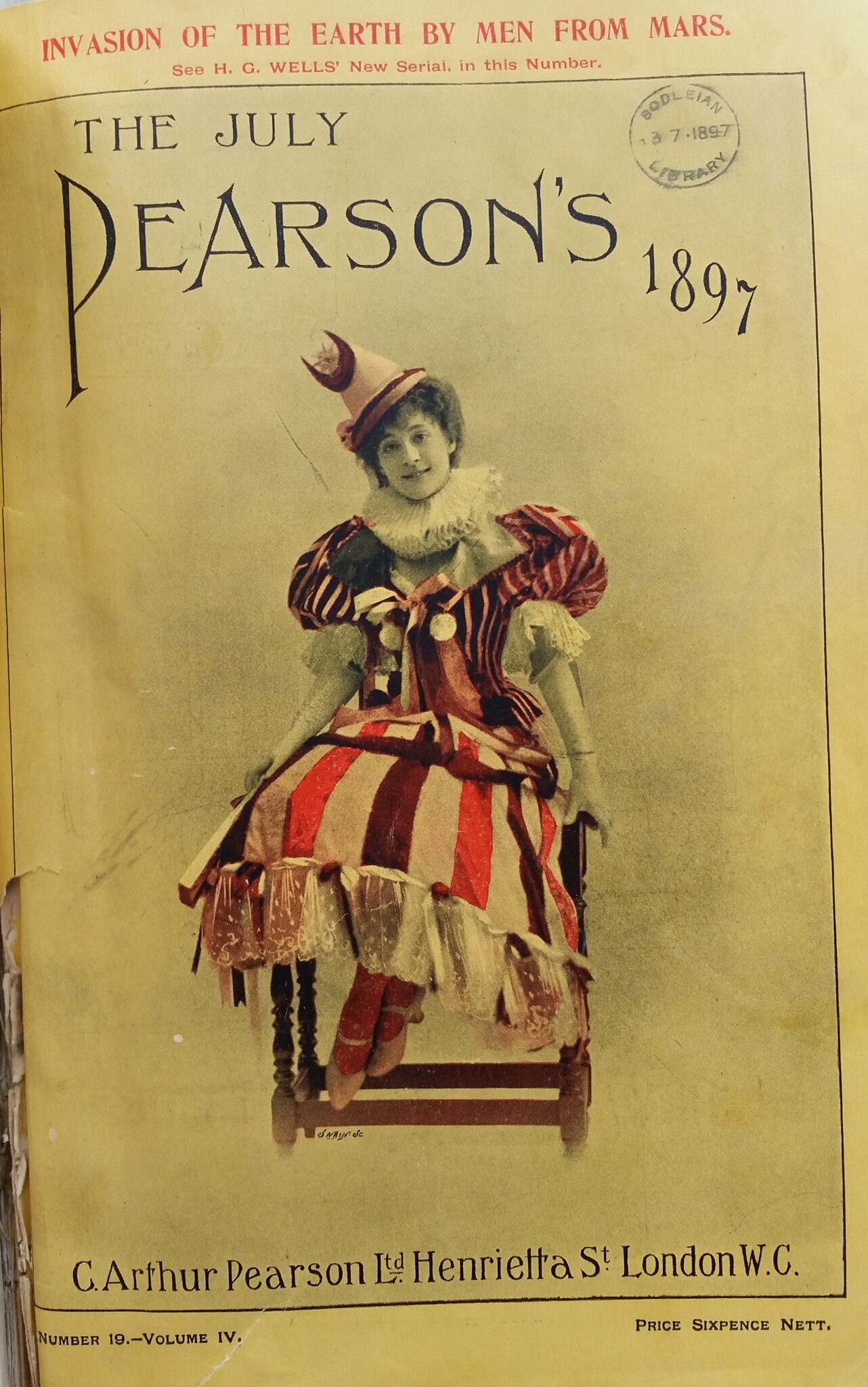

Installment 4 of 9 (July 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book I ("The Coming of the Martians"), Chapters XII-XIII of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions.

This is the cover of the July 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine:

, and so I resolved to go with the artilleryman

GANGNES: In the 1898 edition of the novel, this phrasing is changed and expanded in a way that begins to flesh out the artilleryman as a character. In the serialized version, we never see the artilleryman again after this installment, but he returns and serves a large role in the 1898 edition. See text comparison page and another note on the artilleryman farther down this page.

’luminium

GANGNES: short for "aluminium" (British; American aluminum)

From MCCONNELL 176: "First isolated in 1825, aluminum ... began to be produced in massive quantities only after the discovery, in 1866, of a cheap method of production by electrolysis."

“It’s bows and arrows against the lightning, anyhow,”

STOVER: "It is the inequality of combat, magnified, between French and German forces in the Franco-Prussian War."

GANGNES: In addition to STOVER's note, consider the larger scope of nineteenth-century European imperialism; the 1890s were a time when the British empire was nearing its decline, and The War of the Worlds was one of many well-known novels written at the end of the century that addressed imperialism. Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (serialized in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in 1899 before being collected) tells of a real-life imperial experience, but Bram Stoker's Dracula, which was, like The War of the Worlds, published in 1897, is a very different kind of novel that nonetheless explores the idea of Britain being invaded by a superior entity in the way the British invaded colonial lands.

Numerous Wells scholars have written on the "reverse colonization" and "Empire comes home" nature of The War of the Worlds. As Robert Silverberg writes, "[Humans] simply don’t matter at all [to the Martians], any more than the natives of the Congo or Mexico or the Spice Islands mattered to the European invaders who descended upon them to take their lands and their treasures from them during the great age of colonialism.” Likewise, Robert Crossley observes, "The Martians do to England what the Victorians had done to Africa, Asia, and the South Pacific--and Wells intended that his fellow English imperialists taste a dose of their own medicine.”

Sources:

More information:

The decapitated colossus

GANGNES: The scene beginning at this point and running through the end of the chapter was significantly revised with dozens of small rewordings. In addition to deemphasizing some of the narrator's personal emotions, as Wells does in other parts of the novel, these changes show Wells grappling with exactly how to describe the appearance and movement of the Martian fighting machines and the nigh-cinematic scene of destruction that makes this novel highly suited to visual adaptation. See text comparison page.

When I realised that the Martians had passed I struggled to my feet, giddy and smarting from the scalding I received, and for a space I stood sick and helpless between the drifting steam and the suffocating, burning, and smouldering behind. Presently, through a gap in the thinning steam,

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 version. This is another instance of removing the narrator's commentary on his own feelings and reactions, especially those that seem weak or cowardly. See text comparison page.

I do not clearly remember the arrival of the curate

GANGNES: From this point through the end of the installment is one of the most heavily reworked scenes in the novel. There are significant cuts, additions, rearrangings, and rephrasings. The revisions alter the curate's mood and the narrator's emotional and intellectual responses to the curate's outburst. Through these edits, Wells seems to be grappling with how to most effectively present a critique of religion. See text comparison page.

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom

GANGNES: Reference to Proverbs 9:10: "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom: and the knowledge of the holy is understanding." This line is part of the cuts made to this installment between the serialized version and the volume. See text comparison page.

The smoke of her burning goeth up for ever and ever

GANGNES: With his mind still on the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, MCCONNELL identifies this quote as referencing Genesis as well. STOVER and DANAHAY both identify the reference as coming from Revelation, but disagree on which passage. An examination of each passage would suggest that Stover is correct, though DANAHAY's passage also describes destruction.

From MCCONNELL 188: "A slightly inaccurate quotation from Genesis 18:28."

From STOVER 130: reference to Revelation 19:3: "Hallelujah! The smoke from her goes up for ever and ever." ("her" = the harlot of Babylon, Rome)

From DANAHAY 96: "Revelations[sic] 6:16-17 describes the end of the world in these terms."

hide them from the face of Him that sitteth upon the throne?

From STOVER 131: reference to Revelation 6:16

GANGNES: Note that this is the passage DANAHAY cited earlier in the curate's speech.

Installment 3 of 9 (June 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book I ("The Coming of the Martians"), Chapters IX-XI of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions.

This is the cover of the June 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine:

that a dispute had arisen at the Horse Guards

GANGNES: STOVER corrects HUGHES AND GEDULD's annotation, though does not mention them specifically in the note, despite referencing them in other notes.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 206: "Their notion is that there was an operational or tactical dispute--about how to deal with the situation--among the officers of the elite Horse Guards at the Horse Guard barracks (a building in central London opposite Whitehall). The Horse Guards are the cavalry brigade of the English Household troops (the third regiment of Horse Guards is known as the Royal Horse Guards)."

From STOVER 94: Horse Guards here "is a shorthand reference to the British War Office, located on Horse Guards Parade near Downing Street in London. As Americans refer to the Department of Defense as 'The Pentagon' after its office building, so the British called its War Office 'the Horse Guards.' Not to be confused with the Household Calvary regiment The Royal Horse Guards, even then a tourist attraction when on parade."

They

GANGNES: In the 1898 edition, this sentence (slightly edited) is preceded by, "It hardly seemed a fair fight to me at the time." In the revised version we are offered this bit of foreshadowing and characterization without a strong emotional component. See text comparison page.

Addlestone

GANGNES: village to the north and slightly east of Woking

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: "a village in Surrey, about four miles north of Woking"

As soon as my astonishment would let me

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. Another removal of the narrator's emotions. See text comparison page.

But that strange sight of the swift confusion and destruction of war, the first real glimpse of warfare that had ever come into my life, was photographed in an instant upon my memory.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. Another removal of the narrator's emotional responses to the invasion. The "loss" here is part of the novel's discussion of photography and photographic war journalism specifically. The chapter ends (after "that quivering tumult") with an additional sentence: "I overtook and passed the doctor between Woking and Send." See text comparison page.

I wanted to be in at the death.

GANGNES: The 1898 volume adds "I can best express my state of mind by saying that" to the beginning of this sentence. The change softens the impact of the narrator's emotions by adding an analytical "stepping back" from his feelings at the time. See text comparison page.

I gripped the reins, and we went whirling along between hedges, and emerged in a minute or so upon the open common.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

And this Thing! How can I describe it?

GANGNES: This passage through the next page is the most striking and detailed description of the Martian fighting machines in the novel. Despite the degree of detail offered by the narrator, the machines' physical appearance has been depicted quite differently across various illustrations. Wells made his dislike of Goble's illustrations clear in a passage he added to what would become Book II, Chapter II of the 1898 volume. See Installment 8. He also cut and changed some phrasing to deemphasize comparisons to human technologies. See text comparison page.

in its wallowing career

From DANAHAY 76: in its path

GANGNES: In the 1898 edition, "wallowing" is removed.

But

GANGNES: The 1898 edition adds "That was the impression those instant flashes gave" before this sentence. See text comparison page.

imagine it a great thing of metal, like the body of a colossal steam engine on a tripod stand

GANGNES: The 1898 volume changes this to simply "imagine it a great body of machinery on a tripod stand." This seems likely to be part of Wells's negative response to Warwick Goble's depictions of the Martian fighting machines, which resembled known human technology more than Wells would have liked. See text comparison page, note on "The Terrible Trades of Sheffield" below, and the additional passage in what would eventually become Book II, Chapter 2 in the 1898 volume.

In this was the Martian.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. Perhaps the sentence was thought to be redundant or that it revealed a piece of information the narrator could not have known at the time. See text comparison page.

So

GANGNES: The 1898 volume inserts "And in an instant it was gone." and a paragraph break before this sentence. See text comparison page.

simply stupefied

GANGNES: The 1898 volume replaces this phrase with "in the rain and darkness"; another instance of deemphasizing the narrator's emotions in favor of a more "objective" perspective. See text comparison page.

The steaming air was full of a hot resinous smell.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

two or three distant

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

, but I did not care to examine it

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

I saw nothing unusual in my garden that night, though the gate was off its hinges, and the shrubs seemed trampled.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

My strength and courage seemed absolutely exhausted. A great horror of this darkness and desolation about me came upon me.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. Another clear instance of removing references to the narrator's emotional and physical responses to his predicament. See text comparison page.

I felt like a rat in a corner.

GANGNES: This is cut from the 1898 volume and a paragraph break is added to separate out the final sentence. See text comparison page.

Street Chobham

GANGNES: This should be Cobham, which was confused with Chobham--a village to the northwest of Woking mentioned several times in the novel. Cobham is five miles to the east and slightly north of Woking on the way from Woking (via Byfleet) to Leatherhead. It seems that either Wells or the editors of Pearson's mistakenly wrote "Street Chobham" instead of "Street Cobham"; the error is corrected in the 1898 version.

The light itself came from Chobham.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

I was so delighted

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

Hist!

GANGNES: an exclamation to quietly get someone's attention; similar to "Psst!"

I asked him a hundred questions.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

thing like a huge photographic camera

GANGNES: The 1898 volume replaces this with "complicated metallic case, about which green flashes scintillated" and changes "funnel" to "eye." Again we "lose" language about photography, despite the fact that the novel as a whole retains such references in other areas. See text comparison page.

saw a star fall from Heaven

GANGNES: A possible reference to, or evocation of, Lucifer as the "Morning Star" falling from Heaven. See Isaiah 14:12 and Luke 10:18. More information at the Wikipedia entry for Lucifer.

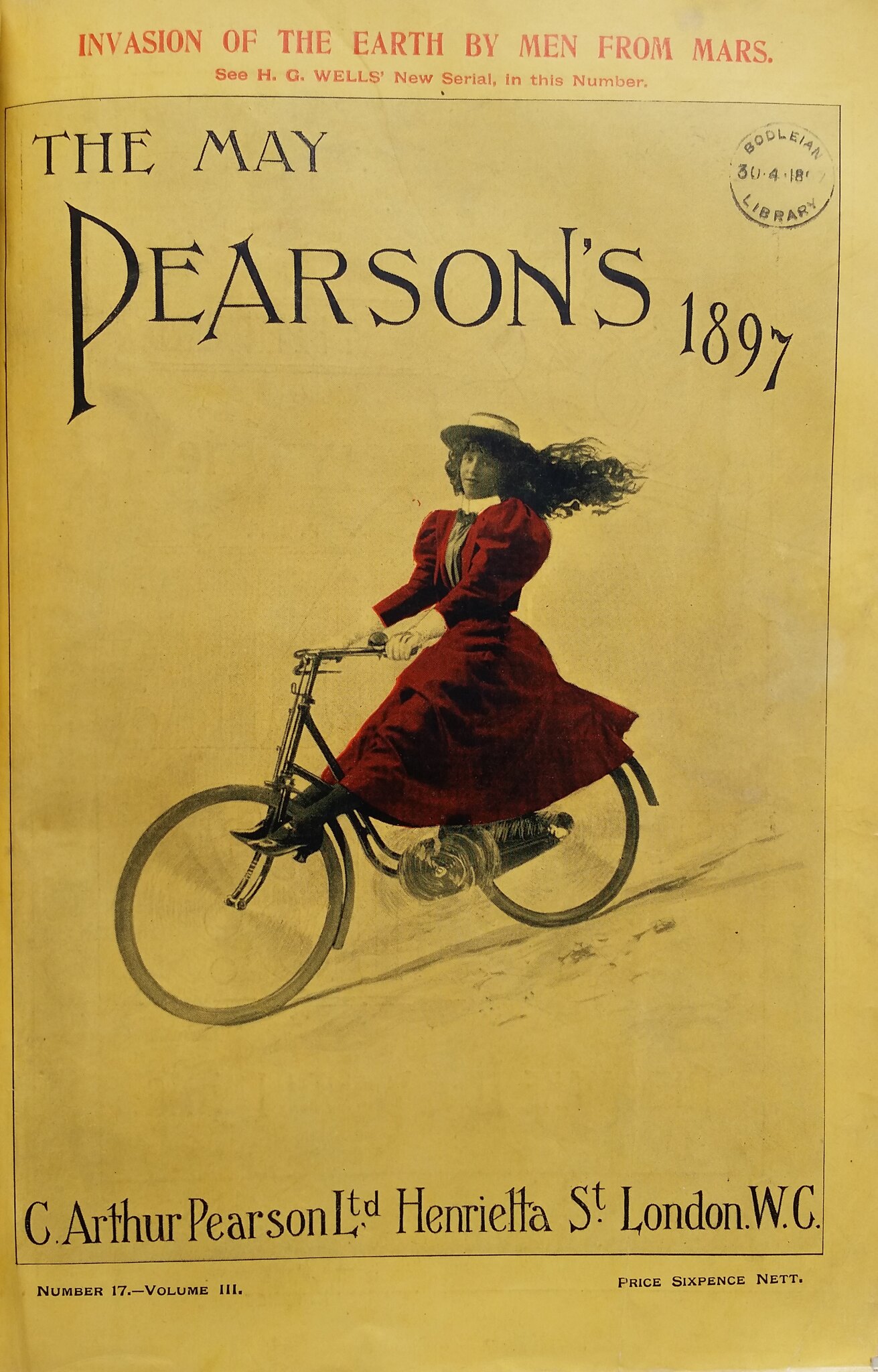

Installment 2 of 9 (May 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book I ("The Coming of the Martians"), Chapters V-VIII of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions.

This is the cover of the May 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine:

waving a white flag

GANGNES: which is to say, signalling peace or surrender

Deputation

GANGNES: In this case, as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary: "a body of persons appointed to go on a mission on behalf of another or others"

And then something happened, so swift, so incredible, that for a time it left me dumbfounded, not understanding at all the thing that I had seen.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. This is another instance (see Installment 1) where a comment about the narrator's feelings has been removed. See text comparison page.

the ghost of a beam of light

GANGNES: The differences between Cosmo Rowe's illustrations and Warwick Goble's exemplify the difficulties presented for illustrators by invisibility or near-invisibility. Different illustrators have chosen to depict the heat ray in different ways that make clear the cause-and-effect relationship of the ray being pointed and its targets being lit on fire. Usually this requires a visual representation, even though the ray is described as invisible.

by the light of their destruction

GANGNES: The narrator is only able to see the people who are burning because the fire burning on their bodies creates light.

It was the occurrence of a second, this swift, unanticipated, inexplicable death.

GANGNES: This sentence was cut from the 1898 volume. It begins a section of the text--from here through the end of Chapter V, that was heavily revised in the transition from serialized version to volume. Again, most of these revisions deemphasize the emotional (and sometimes physical) responses of the narrator to the Martians. This takes the focus of Wells's depictions of the Martians off of the narrator and perhaps allows the reader to form their own emotional response with minimal mediation from the narrator. See text comparison page.

the peace of the evening

GANGNES: like the peace that the white flag was supposed to signal

mounted

GANGNES: riding a horse

collision

GANGNES: In this case, an attack or conflict. Stent and Ogilvy sent their telegraph before there was any sign of overt hostility from the Martians; they contacted the barracks so that the soldiers might come to the pit and protect the Martians from being attacked by humans, not the other way around.

To think of it brings back very vividly the whooping of my panting breath as I ran. All about me gathered the invisible terrors of the Martians, that pitiless sword of heat seemed whirling to and fro, flourishing overhead before it descended and smote me out of life.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. This is another instance of deemphasizing the narrator's emotional and physical responses to the Martians; the replacement sentence from the volume reads: "All about me gathered the invisible terrors of the Martians; that pitiless sword of heat seemed whirling to and fro, flourishing overhead before it descended and smote me out of life." See text comparison page.

ran a little boy

GANGNES: A macabre parallel to the "little boy" who was crushed in the previous scene.

Perhaps I am a man of exceptional moods. I do not know how far my experience is common. At times I suffer from the strangest sense of utter detachment from myself and the world about me; I seem to watch it all from the outside, from somewhere inconceivably remote, out of time, out of space, out of the stress and tragedy of it all. This feeling was very strong upon me that night. Here was another side to my dream.

GANGNES: This is one of a handful of sections that was not cut from the 1898 volume where the narrator explicitly evaluates his own mental and emotional state. The rumination here evokes associations with depression and the feelings of isolation it can cause. It is not clear whether Wells is speaking from experience in this instance. From a narrative perspective, asides like this may call the narrator's reliability into question; he cannot function as an objective journalist figure (indeed, no journalist is "objective") if he is emotionally compromised.

It seemed impossible to make these people grasp a terror upon which my mind even could not retain its grip of realisation.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. This is yet another instance where a comment about the narrator's feelings has been removed. There are a few smaller edits in the next few paragraphs that have a similar effect. Some refer to the narrator's wife's emotional responses as well. See text comparison page.

incredible

GANGNES: In this instance, unbelievable; the narrator is relieved that his wife believes his story about what happened to him because his neighbors did not.

Times

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 205: Britain's most prestigious daily newspaper, est. 1788. By the time Wells was writing this novel its politics were mostly Liberal Unionist.

GANGNES: The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism lists the Times' date of establishment as 1785 rather than 1788; this discrepancy is due to the fact that it was originally titled the Daily Universal Register before its name change in 1788. In its early days it contained parliamentary reports, foreign news, and advertisements, but soon expanded its contents. Under the editorship of Thomas Barnes in the early 1800s it became a "radical force in the context of the liberalizing reforms of the early part of the [nineteenth] century. It continued to exert a radical influence under subsequent editors (including John Thaddeus Delane). The paper included reports from influential foreign correspondents who covered major European conflicts that were of interest to Britain. When Thomas Cherney became its editor in 1878 and was succeeded in 1884, the paper began to become more conservative and pro-Empire. It has changed ownership but is still published today.

Source:

Daily Telegraph

GANGNES: See annotation on Installment 1 regarding the Telegraph.

argon

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 205: "a chemically inactive, odorless, colorless, gaseous element, no. 18 on the Periodic Table of the Elements. It had just been discovered and was in the news. Wells had written it up in 'The Newly Discovered Element' and 'The Protean Gas,' Saturday Review 79 (February 9 and May 4, 1895): 183-184, 576-577."

GANGNES: The above articles from the Saturday Review are available in scanned facsimile here ("The Newly Discovered Element") and here ("The Protean Gas").

shell

GANGNES: An artillery projectile. See Wikipedia entry) on different kinds of shells.

receiving no reply—the man was killed—decided not to print a special edition

GANGNES: Because the newspapers didn't hear from Henderson after he sent a telegram with the news about the capsule's landing, the newspaper decided that it must have been a hoax, so it did not report a story on it. People have been murdered by the Martian heat-ray by this point, and hardly anyone who wasn't at the pit knows about the incident.

love-making

GANGNES: In this case, courting.

A boy from the town, trenching on Smith’s monopoly, was selling papers with the afternoon’s news.

GANGNES: MCCONNELL is somewhat at odds with HUGHES AND GEDULD and STOVER here; H&G's identification of "Smith" as referring to the newsagent W. H. Smith is important to the print culture of Victorian Britain. I include MCCONNELL to show that critical/annotated editions are not infallible.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 205: "Cutting into or 'poaching on' W. H. Smith's monopoly of selling newspapers inside the station. The chain of W. H. Smith to this day has the exclusive rights to selling newspapers, magazines, and books in m any British railroad stations."

From MCCONNELL 153: "'Trenching' means encroaching. The newsboy is selling his papers at a station where Mr. Smith has a permanent newsstand."

From STOVER 91: "Reference to W.H. Smith, whose chain of stationery stores to this day has the exclusive rights to sell newspapers, books, and magazines in British railway stations."

Aldershot

GANGNES: town to the southwest of Woking

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: "Since 1855 an important garrison town in Hampshire, thirty miles southwest of London and about ten miles west of Woking, Surrey.

north-west

GANGNES: As HUGHES AND GEDULD point out (see below), this is a mistake that was not corrected in any of the novel's revisions. The error is somewhat jarring considering that Wells painstakingly situates the Martian invasion at extremely specific real locations. For more information on where this project situates the landing site, see the map page on The (De)collected War of the Worlds.

HUGHES AND GEDULD 206: "This is a slip. The second cylinder falls to the northeast ... in or near the 'Byfleet' or 'Addlestone' Golf Links (really the New Zealand Golf Course, then the only course thereabouts and the one Wells must mean)."

Soon after these pine woods and others about the Byfleet Golf Links were seen to be on fire.

GANGNES: In the 1898 volume, this sentence is replaced with simply, "This was the second cylinder." The change of a chapter's end in this way produces quite a different effect. The serialized sentence heightens the drama and serves as a very effective cliffhanger by evoking an image of destruction. The shorter, more straightforward chapter end sentence from the 1898 volume is freed from the pressure of contributing to a cliffhanger. It has a more objective, informative, journalistic tone while still promising action in the next chapter. See text comparison page.

Daily News

GANGNES: Daily News here is changed to Daily Chronicle in the 1898 volume and subsequent editions. The discrepancy between Daily News in the serialized version and Daily Chronicle in the volume could be due to an error on Wells's part that was corrected for the 1898 edition.

The Daily News (1846-1912) was first advertised as a "Morning Newspaper of Liberal Politics and thorough Independence," set up as a rival to the Morning Chronicle. It was edited by Charles Dickens at its launch. The paper "advocated reform in social, political, and economic legislation, fought for a Free Press in supporting the repeal of the Stamp Act, campaigned for impartial dealings with the natives of India and supported Irish Home Rule." It was known for its detailed war reporting, which boosted its circulation.

The Daily Chronicle was a later name (beginning in 1877) of the Clerkenwell News (1855-1930). The paper was "liberal and radical," with a daily column entitled "The Labour Movement" featured in the 1890s. Interestingly, the paper eventually merged with the Daily News (becoming the News Chronicle), but not until 1930--after even the 1925 edition of The War of the Worlds, let alone the 1898 edition.

Source:

Chertsey

GANGNES: town to the north of Woking, farther than Ottershaw

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: "A small town about three miles north of Woking, Surrey."

Installment 1 of 9 (April 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book I ("The Coming of the Martians"), Chapters I-IV of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions.

This is the cover of the April 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine:

Cosmo Rowe (1877-1952)

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 217: In 1896 H. G. Wells and his agent attempted to get illustrations for The War of the Worlds from Cosmo Rowe, but only succeeded in securing two, both of which appeared in Pearson's and one in Cosmopolitan.

GANGNES: Cosmo Rowe (William John Monkhouse Rowe, 1877-1952) was a British illustrator active during the late Victorian period and thereafter. He was a friend of Wells's and of designer William Morris (1834-1896).

Rowe's illustrations for The War of the Worlds appear in the April 1897 (installment 1, first page) and May 1897 (frontispiece) issues of Pearson's Magazine; they are the only illustrations for the Pearson's War of the Worlds that were not done by Warwick Goble.

Biographical source:

More information:

dreaming themselves the highest creatures in the whole vast universe

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

carry warfare sunward

GANGNES: Which is to say, invade Earth and destroy human beings; Earth is closer to the Sun than Mars is.

Daily Telegraph

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 200: The Daily Telegraph was established in 1855 and to this day is still one of Britain's foremost national newspapers.

From MCCONNELL 127: The Daily Telegraph (founded 1855) catered to the middle class; it featured "flamboyant, often sensational journalism."

GANGNES: Contrary to MCCONNELL, the Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism writes that the Daily Telegraph (1855-present; founded as the Daily Telegraph and Courier) originally catered to a "wealthy, educated readership" rather than the middle class. Though it became associated with Toryism in the twentieth century, its politics in the nineteenth century were first aligned with the Whigs, especially in its liberal attitude toward foreign policy. This changed somewhat in the 1870s when it supported Benjamin Disraeli, and the paper became more Orientalist under the editorship of Edwin Arnold. The Telegraph also promoted the arts.

Source:

just a second or so under twenty-four hours after the first one

GANGNES: Presumably this timing is necessary because the capsules are all being "aimed" at roughly the same area geographically; the cylinders need a "straight shot" from their giant gun (cannon), and the Earth takes 24 hours to rotate back to roughly the same position in reference to the Sun. It may also take a significant amount of time to reload a new capsule into the gun.

For in those days there was no terror for men among the stars.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

Isleworth

GANGNES: to the northeast of Woking, a little over halfway between Woking and central London

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: "Residential district of greater London, just east of Kew Gardens, about eight miles west-southwest of the center of the city."

Winchester

GANGNES: city near the south coast of England; Woking lies to the northeast midway between Winchester and London

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 235: "A city in southern England, in Hampshire, about sixty miles southwest of London. Famous for its Cathedral (founded 1079) and its public school (Britain's oldest)."

French windows

GANGNES: tall windows that open out as glass double-doors

Woking

GANGNES: the town in which the first Martian cylinder lands and the first part of the narrative action takes place; the narrator lives in the area

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 235: "A town in Surrey, about four miles north of Guildford and twenty-three miles southwest of central London."

Berkshire, Surrey, and Middlesex

From DANAHAY 47: contiguous English counties

GANGNES: Most of the novel takes place in Surrey and central London.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: Berkshire is "a county of southern England bordered by Oxford and Buckingham (on the north), Gloucester (on the northwest), Hampshire (on the south), Surrey (on the southeast), and Wiltshire (on the west)."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 234: Surrey is "a county of southern England bordered by Buckingham, Middlesex, and London (on the north), Berkshire (on the northwest), Kent (on the east), Hampshire (on the west), and Sussex (on the southwest). It is drained by the rivers Thames, Wey, and Mole."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 231: Middlesex is "a major residential district that forms a sizeable part of London's metropolitan area. It borders Essex and London (on the east), Surrey (on the south), Hertford (on the north), and Buckingham (on the west)."

Weybridge

GANGNES: a town to the northeast of Woking, between Woking and London

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 235: "a north Surrey town about four miles northeast of Woking and seventeen miles southwest of central London"

dull radiation

GANGNES: the heat radiating from the cylinder (not harmful/nuclear radiation)

public house

GANGNES: British "pubs"/bars

Henderson, the London journalist

GANGNES: There are quite a few real "Henderson"s associated with the nineteenth-century press. However, given the role of "Henderson" in this novel, it seems unlikely that the name was meant to refer to any particular journalist.

Source:

Few of the common people in England had anything but the vaguest astronomical ideas in those days.

GANGNES: This statement implies that most English people became far more familiar with astronomy after their country was invaded by aliens from another planet.

A MESSAGE RECEIVED FROM MARS

GANGNES: This is one of the many instances in which newspapers release information that is incorrect, vague, or unhelpful. Throughout the novel, the narrator criticizes the inaccuracy and mercenary nature of the press.

three kingdoms

GANGNES: You will see below that three different annotated editions of the novel give three different definitions of this reference, and they do not agree as to whether it is Wales or Ireland that is meant to be the "third kingdom."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 203: England, Ireland, and Scotland

From STOVER 70: Of Great Britain

From DANAHAY 52: England, Scotland, and Wales

Chobham Road

GANGNES: road leading to Chobham from Woking

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: "a thoroughfare bordering the north side of Horsell Common, located about a mile and a half north of Woking, Surrey"

A big greyish rounded bulk, the size perhaps of a bear, was rising slowly and painfully out of the cylinder.

GANGNES: Visual depictions of Wells's Martians, like those of their fighting-machines, have varied widely. Part of this is due to the fact that, even though they are described at length, the narrator still has difficulty wrapping his head around how to relate their appearance to terrestrial creatures. Most depictions resemble something squidlike, but Spielberg's 2005 film) extrapolates from the tripod machines and gives the Martians three appendages.

More information:

You who have only seen the dead monsters in spirit in the National History museum, shriveled brown bulks, can scarcely imagine the strange horror of their appearance.

GANGNES: The 1898 volume removes this address to the reader and its reference to the Natural History museum. See text comparison page. Here is the revised sentence: "Those who have never seen a living Martian can scarcely imagine the strange horror of its appearance." In general, appeals to the reader (i.e., usage of "you" or similar) are minimized in the volume. Such revisions may aid in making the novel's tone more journalistic.

At that my rigour of terror passed away.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page. This is one of many instances in which the volume omits the narrator's references to his own feelings, especially somewhat cowardly/frightened reactions. Like appeals to the reader, personal responses could undermine the journalistic tone that characterizes most of the novel.

I could not avert my face from these things

GANGNES: A reference to the irresistible quality of Gorgons; see note on "Gorgon" above.

road from Chobham or Woking

GANGNES: southeast of Chobham or north from Woking