- Last 7 days

-

www.google.com www.google.com

-

-

www.technologyreview.com www.technologyreview.com

-

OpenClaw, like many other open-source tools, allows users to connect to different AI models via an application programming interface, or API. Within days of OpenClaw’s release, the team revealed that Kimi’s K2.5 had surpassed Claude Opus and became the most used AI model—by token count, meaning it was handling more total text processed across user prompts and model responses.

Wow, I had no idea that Kimi 2.5 had subbed in for Claude Opus so quickly.

-

-

www-jstor-org.libproxy.washu.edu www-jstor-org.libproxy.washu.edu

-

Sincemost US cities depended on property and income tax revenues to providemunicipal services and maintain infrastructure, this eroded municipalrevenues

And then people went out of work, white flight is a real bitch ya know.

-

The economic shockwaves created by these events helped producetwo recessions and the worst economic downturn since the Great De-pression.

Which the midwest felt disproportionately as their industry was outsourced

-

the demise of the New Deal order and rise of anew conservative/neoliberal order.1

Party realignment in black and black

-

-

-

people11 make things (texts, baskets, performances), people make relationships, people make culture.

very simple way of explaining how culture is constructed

-

constellation

use of word is discussed in class

term

-

It's interesting how you chose De Certeau to talk about rhetoric—not a lot ofpeople really think of him as a "rhetorician.

I didn't know this about De Certeau

-

as always-already rhetorical

term

-

to understand how the making of culture occurs through everyday practice instead of through official,sanctioned dominant acts of cultural installation (xiv).

i like this line

-

is to surface, recognize, extend and intervene in how rhetoric scholars think about culture

Objective/aim/motive

-

scholars in rhet/comp rely on this object-oriented approach to cultures because itallows us to select "exemplars" from specific oppressed cultural traditions as a way of feeling good about howinclusive our discipline has become.

this feels like a call out

-

"object-oriented,"8 we mean scholarship that identifies "culture" as an object of inquiry, one that can be isolated fromother human, economic, political, geographical, historical frameworks that exist around and within it.

Object Oriented Definition

-

anthropology, sociology, cultural studies andfrom the borrowings that folks in rhet/comp studies have initiated from these inter/disciplines.

I like that they highlight the particular areas

-

as a static object. T

I can agree with this. Comes from my past reading on culture

-

a partialconstruction of our definition of the practice of cultural rhetorics.

their aim/objective

-

is an important one for the discipline ofrhet/comp, it is not the model that guides us.

them making clear distinctions

-

r several reasons.

reasoning behind the style of the piece

-

the kind of place where the audience is asked to participate inthe performance

LOVE!

-

as themselves, representing their ownexperiences with cultural rhetorics practice/methodology apart from the collective

Its good to establish this early

-

, the questions that s/he asks have helped us think more deeply, more persistently, and more broadlyabout our collective work and its relationship to the discipline of rhetoric and composition.

I wonder if this is a fictional character. someone they have created.

-

name using one of the original languages of the place6 where much of this article waswritten,

a way of (kinda) honoring the space that they are in

-

—the kindAristotle liked best

nice

-

working through ideas for the article, yes, but also working throughour relationships with one another; renewing familiar patterns, starting new ones.

This paints a nice collaborative picture

-

and sage theentire house before I head into town to bring back local supplies—smoked whitefish and pasties.

cultural practices

-

This is Odawa territory

?

-

a writing retreat to finish this article.

I wonder how much they had written at the point MALEA wrote this prolouge

-

-

openclassrooms.com openclassrooms.com

-

liens

a { color: black; }

-

-

bookshelf.vitalsource.com bookshelf.vitalsource.com

-

Lasting relationships with diverse individuals in a learning community—peers, faculty, and staff

My leadership qualities are more of resilience and team appreciation which relate to Lightning Mcqueen’s leadership qualities because he learns to work in a team and keep pushing through even when he just wants to get the end result and not do the work.

To develop my leadership qualities I should talk to new people, maybe even join a group with the same interests as me, and keep pushing to ask for help with the struggles of college.

The greatest barrier I have in accomplishing this is fear. I get scared to fail, so I hold back and don’t let opportunities succeed as well as I could which is something I am trying to work on.

-

-

-

“Fordism”–that was distinc-tive to the mid-twentieth century upper Midwest, but which was widely mim-icked around the world (Gramsci 1989).

Work, stability.

-

butdue to disconnection between communities and their party representatives

Media mobilizes real grievences

-

More importantly, the inevitable transformation and decline of place will shapethe values of those living there, just as the initial development of industrial soci-ety once did

Getting ignored dismantled the institutions that kept the midwest democratic and now they are revolting

-

kleptocracy

System where powerful steal resources

-

Organizations, institutions, networks and associations, in turn, poten-tially shape these into political subjectivities and moral values which can beinstrumentalized and expressed in politics, development strategies, and culture,which we can summarize as a ‘communal ethos’

Individuals feeling is shaped by the institutions in their community

-

Americans and from mostAmerican communities.

Which are really situated in the homogeneous midwest

-

not the economic protections that would facilitatebroader social inclusion.

Which is in part a coastal elitist thing

-

In Detroit alone the decline in black voter turnout wasseveral times the margin of Clinton’s loss in Michigan.

Not inspired/ felt supported by clinton

-

thefew rural counties that were not already solidly Republican and (2) post-industrial counties (see Figure II)

Post-industrial is the midwest

-

. For the first time in the history of thetwo parties, Republicans did better among poor white voters than among afflu-ent whites

Saying this was a long time coming but I have trouble buying that it was not also connected to trump

-

this is a notable contrast to the ethnona-tionalist and protectionist candidates who preceded him

who lost

-

Today, the Democratic Party is a party of professionals, minoritiesand the New Economy

As opposed to the once blue collar worker

-

The counties Trump won – over 2,000 more in number –accounted for a much smaller share of GDP

Left behind

-

but what is more recent isthe collapse of the institutions that had been built to incorporate industrialworkers and their communities into the mainstream political life of the country,including governance arrangements, work and consumption arrangements, civicassociations, social policies, party organizations, and labour unions

Why now?

-

to explain the largely enthusiastic support for Obama in thesesame counties

How did it shift so quickly in Obamas term though

-

This way of thinkinghas set up an unproductive discussion of the relative explanatory power ofrace and class.

Which matters much more at the individual level

-

But the collapse of the regional economy has alsoresulted in the collapse of the institutions and organizations that provided thoseconnections.

But the dems might have been oblivious

-

with the plight ofthe industrial Midwes

What is that plight I hope we learn

-

Clinton lost the election because of radicaldeclines in support from within the Democratic coalitio

Same with Harris

-

Due to this, the party pursued poli-cies that would magnify the region’s difficulties rather than alleviate its cir-cumstances

Which pushed them towards republicans

-

From thisperspective we can see that the active dismantling of the Fordist social orderset the region on a divergent path from the rest of the country

what is that

-

revanchism

Seeking to retaliate

-

This paper argues that the election of Donald Trump is the product of a con-fluence of historical factors rather than the distinctive appeal of the victorhimself. B

Ready to buy that

-

-

Local file Local file

-

the first six cholera pandemics

cholera HAS been a troubling thing worldwide

-

the conflicts that arise over competing theoretical interpretations.

conflicts between therohetical perspectives arise from the parts of theory that are left out or what is considered irrelevant

-

-

www.purepen.com www.purepen.com

-

赍发

sponsor

-

小二

a common way to call an inn or restaurant servant

-

-

www.tomshardware.com www.tomshardware.com

-

Meanwhile, under China's 'Eastern Data, Western Computing' initiative in the early 2020s, numerous startups constructed large AI and cloud data centers across western regions of China, where electricity costs are lower, with the goal of serving demand from economically stronger eastern provinces. While the strategy reduced power expenses, it turned out that longer distances increased latency and made these facilities less attractive for many latency-sensitive applications, which limited actual usage

Is this what happened with them? They got,built and weren’t used as much in the end?

-

-

www.jstor.org www.jstor.org

-

highly centralized communistor workers' party;

One party system sustained communism

-

-

www.americanyawp.com www.americanyawp.com

-

Abigail and John Adams Converse on Women’s Rights, 1776

- It Is an Early Call for Women’s Rights Abigail’s request to “remember the ladies” is one of the earliest and clearest arguments for women’s legal protections in American history. She challenges male authority in marriage and government.

- It Shows Women’s Political Awareness. Her letter shows that women were thinking critically about government and justice even if they were excluded from formal power.

- It Exposes Gender Roles in the 18th Century John’s joking tone reflects common attitudes of the time, that women’s demands were not to be taken seriously. His response helps historians understand how deeply rooted patriarchal systems were.

-

-

elgatoylacaja.com elgatoylacaja.com

-

Roganovich, R. C. (2025). Prefacio | El archipiélago. https://elgatoylacaja.com/libros/el-archipielago/prefacio

-

-

www.americanyawp.com www.americanyawp.com

-

Fifthly, They are to have a Governor and Council appointed from among themselves, to see the Laws of the Assembly put in due execution; but the Governor is to rule but 3 years, and then learn to obey; also he hath no power to lay any Tax, or make or abrogate any Law, without the Consent of the Colony in their Assembly

Talking about freedom of choosing their government

-

-

www.washingtonpost.com www.washingtonpost.com

-

Without further federal commitments, 70,000 programs might close, wiping out 3.2 million slots and $9 billion in annual parent earnings,

Establishing what's at stake, showing that not passing the funding isn't a neutral act, it's harmful.

-

come up with a lot of money.

The main focus of the article will be about how much money can be put forward towards childcare

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Synthèse du Séminaire sur l'Enseignement Explicite : Des Coulisses à la Classe

Ce document de breffage synthétise les interventions du séminaire organisé par l'Université de Mons (UMons) et l'Institut d'administration scolaire.

Il détaille les fondements théoriques, les modalités pratiques et les outils de recherche liés à l'enseignement explicite, une approche pédagogique éprouvée pour favoriser l'équité et l'efficacité des systèmes éducatifs.

Résumé Exécutif

L'enseignement explicite (EE) est une approche pédagogique issue de l'observation de pratiques de classe efficaces, particulièrement dans les milieux défavorisés.

Son principe central est de « rendre visible » ce qui est invisible : les démarches cognitives de l'enseignant et les processus d'apprentissage des élèves.

Fondée sur le modèle PIC (Préparation, Interaction, Consolidation), cette méthode suit une progression rigoureuse : ouverture, modelage (« Je fais »), pratique guidée (« Nous faisons »), pratique autonome (« Tu fais ») et clôture.

Au-delà de la transmission des savoirs, l'EE s'applique également à la gestion des comportements et s'appuie sur une « vision professionnelle » que les outils technologiques, comme le suivi oculaire (eye-tracking), permettent désormais d'objectiver.

La formation des enseignants repose sur une collaboration étroite au sein d'une triade (stagiaire, maître de stage, superviseur) visant à transformer le novice en un praticien réflexif capable d'ajuster ses gestes professionnels aux besoins de ses élèves.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Cadre de Référence et Principes Fondamentaux

L'intérêt de l'Université de Mons pour l'enseignement explicite s'inscrit dans une réflexion de vingt ans sur l'amélioration des systèmes éducatifs.

Objectifs de l'Éducation

• Équité et Efficacité : L'objectif est de réduire les écarts entre les élèves et d'élever la moyenne des résultats, tant sur le plan cognitif (instruction) que comportemental (éducation).

• Liberté et Responsabilité : Si la liberté d'enseignement est garantie, elle doit s'appuyer sur des choix documentés et éclairés par la recherche pour éviter les modes passagères.

• Libération du Déterminisme : L'école doit permettre à chaque individu de se libérer des déterminismes sociaux dont il n'est pas responsable.

Le Modèle de l'Enseignant Efficace

L'enseignement est comparé à la médecine ou au sport de haut niveau : c'est un métier complexe qui repose sur des savoir-faire qui ne sont pas innés, mais qui s'apprennent et se développent par l'accumulation de connaissances et la pratique.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2. Le Modèle de l'Enseignement Explicite

L'enseignement explicite n'est pas une théorie abstraite mais une approche issue de recherches corrélationnelles débutées dans les années 70.

La Structure PIC (Préparation, Interaction, Consolidation)

• Préparation (Planification) : Travail de l'enseignant en amont de la classe.

• Interaction : Le cœur de la leçon, décomposé en cinq étapes chronologiques.

• Consolidation : Automatisation des acquis et évaluation.

Les 5 Étapes de l'Interaction en Classe

| Étape | Rôle de l'Enseignant | Description Clé | | --- | --- | --- | | Ouverture | Présenter | Annonce des objectifs, du plan de cours et réactivation des connaissances préalables. | | Modelage | « Je fais » | L'enseignant met un « haut-parleur sur sa pensée » pour expliciter ses démarches à voix haute. | | Pratique Guidée | « Nous faisons » | Vérification constante de la compréhension. L'enseignant questionne les élèves jusqu'à obtenir 80 % de réussite. | | Pratique Autonome | « Tu fais » | L'élève travaille seul. L'enseignant circule pour apporter un support individualisé. | | Clôture | Objectiver | Synthèse de la leçon, métacognition et lien avec la leçon suivante. |

Caractère Itératif : Cette démarche n'est pas figée. Si la pratique guidée échoue, l'enseignant doit revenir au modelage. Elle permet ainsi une différenciation pédagogique réelle en fonction des besoins des élèves.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3. Gestion de Classe et des Comportements

L'enseignement explicite considère que la gestion des apprentissages et la gestion de classe sont deux rouages indissociables : l'un ne peut fonctionner sans l'autre.

L'Objectivation de la Compréhension

L'enseignant doit rendre observable le cheminement de pensée des élèves. On distingue plusieurs types d'objectivations :

• Stéréotypée : « Ça va ? Vous avez compris ? » (Peu efficace car l'élève répond souvent par l'affirmative sans preuve).

• Spécifique : « Peux-tu reformuler avec tes propres mots ? » ou « Cite les caractéristiques de... ».

• Métacognitive : Questionner les étapes par lesquelles l'élève est passé pour trouver une réponse.

L'Enseignement Explicite des Comportements

Plutôt que de punir l'élève qui ne sait pas se comporter, on lui enseigne les attentes sociales.

1. Définir les valeurs : (ex: Respect, Responsabilité, Sécurité).

2. Traduire en comportements observables : Utiliser des formulations positives (ex: « Je marche calmement » au lieu de « Ne pas courir »).

3. Appliquer la démarche EE : Modelage du comportement attendu, pratique guidée et renforcement en contexte réel (classe, couloirs, réfectoire).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4. Vision Professionnelle et Observation des Pratiques

L'expertise enseignante réside dans la capacité à balayer l'environnement, repérer les indices pertinents et raisonner avant d'agir.

Différences entre Novices et Experts (Apports de l'Eye-Tracking)

Grâce au suivi oculaire, la recherche à l'UMons a identifié des différences marquées dans l'observation d'une classe :

• Enseignants Experts / Formateurs :

◦ Focus prioritaire sur les élèves, notamment ceux à risque ou discrets.

◦ Balayage visuel dynamique et itératif (stratégies de « coup d'œil »).

◦ Raisonnement basé sur l'anticipation des conséquences et les cadres théoriques.

• Enseignants Novices / Futurs Enseignants :

◦ Focus excessif sur l'enseignant ou les éléments visuels saillants (bruit, mouvement).

◦ Attention portée uniquement aux élèves « hyper-participatifs » ou très perturbateurs.

◦ Difficulté à se détacher de la gestion disciplinaire immédiate.

Outils de Formation

• Micro-enseignement : Entraînement en milieu sécurisé devant ses pairs avant de faire face à de vrais élèves.

• Grille Miroir : Outil de codage des gestes professionnels permettant un feedback objectif basé sur la vidéo.

• Vidéos enrichies : Utilisation de prompts (indices visuels) pour orienter le regard du novice vers les zones importantes.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5. La Triade de l'Accompagnement en Stage

Le développement du futur enseignant repose sur une interaction entre trois acteurs clés : le stagiaire, le maître de stage (terrain) et le superviseur (institution).

Le Dialogue Collaboratif

La recherche souligne l'importance de dépasser le simple échange « question-réponse » pour viser la co-construction.

• Style de Supervision : Les superviseurs doivent être capables de moduler leur style (directif ou non-directif) comme un musicien change de registre.

• Défis de la Collaboration : Le dialogue peut être freiné par la peur de l'évaluation ou par des visions discordantes entre l'université et le terrain.

• Objectif : Transformer le stage en un espace de réflexion où le stagiaire n'est pas un simple exécutant, mais un praticien capable d'analyser ses propres erreurs comme des leviers d'apprentissage.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Conclusion

L'enseignement explicite est une approche pragmatique qui refuse l'opposition entre instruction et éducation.

En outillant les enseignants avec des gestes professionnels documentés et en développant leur vision professionnelle, ce modèle vise à instaurer une culture de la réussite où l'enseignant est pleinement responsable de la progression de chaque élève, tout en conservant sa liberté pédagogique au sein d'un cadre scientifique rigoureux.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

eLife Assessment

Stearns and Poletti present a technically impressive study that aims to uncover a deeper understanding of microsaccade function: their role in perceptual modulation and the associated temporal dynamics. The question is useful, and advances prior work by adding temporal granularity. However, the strength of the evidence is currently incomplete. Additional analysis is needed to control for the effects of endogenous attention and to demonstrate changes in perceptual performance.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Using high-precision eyetracking, the authors measure foveolar sensitivity modulations before, during, and after instructed microsaccades to a centrally cued orientation stimulus.

Strengths:

The article is clearly written, and the stimulus presentation method is sophisticated and well-established. The data provide interesting insights that will be useful for comparisons between trans-saccadic and trans-microsaccadic sensitivity modulations.

Weaknesses:

Nonetheless, I have major concerns regarding the interpretation of the measured time courses (in particular, inconsistencies in distinguishing enhancement from suppression), the attempt to disentangle these effects from endogenous attention shifts, and the overstatement of the findings' novelty.

(1) Overstatement of novelty

The authors motivate their study by stating that "the temporal dynamics of these pre-microsaccadic modulations remain unknown" (l. 55-56). However, Shelchkova & Poletti (2020) already report a microsaccade-aligned sensitivity time course. I understand that the present study uses shorter target durations and thus provides a more resolved estimate. Nonetheless, a fairer characterization of the study's novelty would be that observers' discrimination performance is continuously measured across the pre-, intra-, and post-movement interval, within the same observers and experimental design. Relatedly, the authors state that it is unclear whether pre-microsaccadic sensitivity modulations reflect "suppression at the non-foveated location, enhancement at the microsaccade target, or both" (l. 70). Guzhang et al. (2024) examined the spatial spread of pre-microsaccadic sensitivity modulations by measuring performance at the PRL, the movement target, and several other equidistant locations. They report that "whereas fine spatial vision is enhanced at the microsaccade goal location, it drops at the very center of gaze". The current authors' reasoning seems to be that performances at locations that are neither the target nor the PRL may behave differently. Why would that be the case? If my understanding is correct, I would recommend incorporating these clarifications into the motivation paragraph, so that readers less familiar with the literature do not overestimate the novelty of the findings. Moreover, and related to point 3, I am unsure if the current analyses provide decisive evidence to distinguish enhancement from suppression, as claimed by the authors.

(2) Distinction from endogenous attention

To "rule out the possible influence of covert attention" (l. 232), the authors compute a cue-aligned in addition to the movement-aligned performance time course. A difference in alignment cannot rule out the influence of a certain mechanism; it can only dilute it. Just like endogenous attention may contribute to the movement-aligned time course, movement preparation will necessarily contribute to the cue-aligned time course, since these timelines are intrinsically correlated: as the trial progresses, observers will be in later and later stages of saccade preparation. For this and several additional reasons, an effect in the cue-aligned time course is in fact expected-and, in my view, clearly present (see below). As the authors themselves note, endogenous attention has been shown to operate within the foveola and should therefore be engaged in the present experiment in addition to movement-related attentional shifts (unless the authors believe that specific design features, e.g., stimulus timing, preclude its involvement?). Regardless of the theoretical considerations, the empirical data show a pronounced, near-linear increase in performance at the target location, with d′ doubling from approximately 1 to 2. Although the interaction between condition and time does not reach significance (p = 0.09), this result should not be taken as conclusive evidence against a plausible and perhaps expected contribution of endogenous attention. I suggest an additional analysis that could more directly address these issues. In previous work (Rolfs & Carrasco, 2012; Kroell & Rolfs, 2025; see Figure 3), the relative contributions of cue-alinged influences and pre-saccadic attention were disentangled by reweighting each data point according to its position on both the cue-locked and saccade-locked timelines. Applied to the present study, the authors could compute, for each cue-to-target offset bin, its proportional contribution to each pre-movement time bin. Microsaccade-locked sensitivities could then be reweighted based on these proportions. As a result, each movement-locked time bin would contain equal contributions from all cue-locked time bins, effectively isolating the effect of microsaccade preparation.

(3) Interpretation and analysis of the time course

(3.1) Discrimination before microsaccade onset<br /> In lines 151-153, the author state "While the enhancement at the target location did not reach significance relative to baseline, the impairment at the non-target location did", suggesting that pre-movement sensitivity advantages for information presented at the target location are due to a decrease in performance at the non-target location and not an enhancement at the target location per se. After analyzing the difference between the two locations, the authors state, "These results show that approximately 100 milliseconds before microsaccade onset, discrimination rapidly improved at the intended target location while decreasing at the non-target location." (l. 159-161). How is the statement that discrimination performance rapidly improved (which is repeated throughout the manuscript) justified by the results?

More generally, the authors may benefit from applying bootstrapping or permutation-based analyses to their data. Such approaches would, for example, allow direct comparisons between congruent and incongruent conditions at every individual time point in Figure 3B and may be more sensitive to temporally confined sensitivity variations while requiring fewer assumptions than analyses based on manually segregated temporal bins and aggregate measures. If enhancement at the target location does not reach significance even in these analyses, all corresponding statements should be removed throughout the manuscript. The term "enhancement" should then be rephrased as "detection advantage" or "relative performance benefit" to emphasize the contrast to enhancement effects classically associated with pre-saccadic attention shifts.

Relatedly, the authors state that pre-microsaccadic enhancement peaks around 70 ms before microsaccade onset, which is earlier than sensitivity enhancements preceding large-scale saccades that often increase monotonically up until movement onset. The authors suggest potential reasons for this in the Discussion, yet an additional one seems conceivable based on Figure 3B. Performances at both the cue-congruent and incongruent location decrease leading up to the movement, reaching values even below their early baselines around 100 ms and 25 ms before movement onset for the incongruent and congruent location, respectively. A spatially non-specific decline that drives sensitivities toward a common absolute minimum may thus dictate the time course of detection advantages. In other words, a spatially widespread decrease in foveolar sensitivity likely contributes to both "suppression" at the non-target location and the decrease in "enhancement" at the target location. If this general decrease is due to saccadic suppression, as the authors suggest, it appears to exert a much more pronounced influence on sensitivity modulations than it does before large-scale saccades (which is interesting). Are there other findings suggesting an increased magnitude of micro-saccadic (as compared to saccadic) suppression? Another potentially related phenomenon is the decrease in pre-saccadic foveal detection performances reported twice before (Hanning & Deubel, 2022; Kroell & Rolfs, 2022). It is possible that whatever mechanism triggers this decrease is engaged by the preparation of microsaccadic and saccadic motor programs alike. In any case, I would ask the authors to acknowledge this general decrease early on to clarify that any currently significant advantage for the target location relies on varied degrees of suppression, and not on true enhancement similar to pre-saccadic attention shifts.

Moreover, in Figure 3C, the final 25 ms before microsaccade onset are excluded from the aggregate measure, presumably since including this interval substantially reduces the effect size. Since the last 25 ms before movement onset is the interval most commonly associated with saccadic suppression, I think that this choice can be justified. Nonetheless, it should be mentioned explicitly in the main text. On a minor note, the authors state that "Performance (evaluated as percent of correct responses) was averaged within a 50 millisecond sliding window, advancing in 1 ms steps (with 24 ms overlap)". Why is the overlap not 49 ms?

(3.2) Discrimination during the microsaccade:<br /> The authors state that "in the "during" trials the target must be presented during the peak speed of the microsaccade." Since the target was presented for 50 ms and the average microsaccade duration was around 60 ms, this implies that the intra-microsaccadic condition includes many trials in which the target overlapped with the pre- or post-movement fixation interval. Were there not enough trials to isolate purely intra-microsaccadic presentations? Are the results descriptively comparable?

(4) Additional analyses

Several additional analyses could strengthen the authors' conclusions. If there are enough trials in which observers erroneously saccaded to the uncued (i.e., wrong) location, these trials could experimentally isolate the influence of pre-microsaccadic attention, assuming that endogenous attention went to the cued location. In addition, the authors speculate whether differences in saccadic and microsaccadic movement latencies may underlie the differences in perceptual time courses. The latency distributions provided in the manuscript look sufficiently broad, such that intra-individual variation could be harnessed to explore this question. Do sensitivity time courses differ before microsaccades with shorter vs. longer latencies?

(5) Clarifications regarding the design

At 50 ms, the duration of the to-be discriminated stimulus, although shorter than in previous investigations, is still rather long. What is the reason for this? I would encourage the authors to state in the main text that the duration of the analyzed/plotted time bins is often shorter than the stimulus duration (i.e., there is some overlap between bins that likely introduces smoothing). In Figure 3A, it would be helpful to plot raw data points computed from non-overlapping bins on top of the moving-window estimates, to allow readers to assess the degree of smoothing and potential temporal delays introduced by this analysis. Moreover, I wonder whether the abrupt onset of the target unmasked by flickering noise masks might induce saccadic inhibition, which would manifest as a transient dip in saccade execution probability. The distributions shown in Figure 2B appear too smoothed or fitted to clearly reveal such a dip. How exactly are all distributions in the manuscript computed (e.g., binning, smoothing, fitting procedures)? Finally, on a minor note, explicitly stating on line 105 that two different orientations can be presented at the cued and non-cued location would help avoid potential confusion.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary and overall evaluation:

The authors assessed how visual discrimination of stimuli in the foveola changes before, during, and after small instructed eye movements (in the "micro" range). Consistent with (and advancing) related prior work, their main finding regards a pre-saccadic modulation of visual performance at the saccade target vs. the opposite location. This pre-saccadic modulation in foveal vision peaks ~70 ms prior to the instructed small saccade.

Strengths:

The study uses an impressive, technically advanced set-up and zooms in on peri-saccadic modulations in visual acuity at the micro scale. The findings build on related prior findings from the literature on smaller and larger eye movements and add temporal granularity over prior work from the same lab. The writing is easy to follow, and the figures are clear.

Weaknesses:

At the same time, the findings remain relatively empirical in nature and do not profoundly advance theoretical understanding beyond adding valuable granularity to existing knowledge. Relevant prior literature could be better introduced and acknowledged. In addition, there remain concerns regarding potential cue-driven attentional influences that may confound the reported effects (leaving the possibility that the reported effects may be related to cue-driven attention, rather than saccade planning/execution per se). There are also some issues regarding specific statistical inferences. I detail these points below.

Major Points:

(1) Novelty framing and introduction of relevant prior literature

At times, this study is introduced as if no prior study explored the time course of changes in visual perception surrounding small (micro) saccades. Yet, it appears that a prior study from the same lab, using a very similar task, already showed a time course (Figure 5 in Shelchkova & Poletti, 2020). While this study is discussed in the introduction, it is not mentioned that at least some pre-saccade time course was already reported there, albeit a more crude one than the one in the current article. Moreover, the 2013 study by Hafed also specifically looked at "peri-microsaccade modulation in visual perception" and also already showed a temporal modulation that peaked ~50 ms before microsaccade onset. I appreciate how the current study differs in a number of ways (focusing on visual acuity in the foveola), but I was nevertheless surprised to see the first reference to this relevant prior finding in the discussion (and without any elaboration). Though more recent, the same could be argued for the 2025 study by Bouhnik et al. on pre-microsaccade modulations in visual processing in V1, which, like the Hafed study, is first mentioned only in the discussion. Perhaps these studies could be introduced in the paragraph starting at line 48, or in the next paragraph, to do better justice to the existing literature on this topic when motivating the study. This would likely also help to better point out the major advances provided by the current study.

Relatedly, in Shelchkova & Poletti (PNAS, 2020), an apparently similar congruency effect on performance was reported >200 ms milliseconds before saccade onset, as evident from Fig 5 in that article. How should readers rhyme this with the current findings? Ideally, the authors would not only acknowledge that such a time course was already reported previously, but also discuss the discrepancies between these findings further: why may the performance effects appear much earlier in this prior study compared to in the current study, where the congruency effect emerges only ~100 ms prior to the instructed small saccade?

(2) Saccade- or cue-driven? (assumption that attention is unaltered in failed saccade trials)

Because the authors used a cue to instruct saccade direction, it remains a possibility that the reported modulations in visual performance may be driven directly by the spatial cue (cue-related attentional allocation), rather than the instructed small saccade per se. While the authors are clearly aware of this potential confound, questions remain regarding the convincingness of the presented control analyses. In my view, a more compelling control would require an additional experiment.

The central argument against a cue-locked (purely attentional) modulation is the absence of a performance modulation in so-called "failed" saccade trials. However, a key assumption here is that putative cue-driven attention was unaltered in these trials. This is never verified and, in my opinion, highly unlikely. Rather, trials with failed microsaccades could very well be the result of failing to process the cue in the first place (indeed, if the task is to make a saccade to the cue, failure to make a saccade equates failure to perform the task). In such trials, any putative cue-driven influences over spatial attention would also be expected to be substantially reduced. Accordingly, just because failed saccade trials show little performance modulation does not rule out cue-driven attention effects, because attention may also have "failed" in these failed saccade trials. The control for potential cue-driven attention effects would be more convincing if the authors included a condition with the same cues, where participants are simply not instructed to make any saccades to the cues. Unfortunately, such an experimental condition appears not to have been included here. The author may still consider adding such a control experiment.

Another argument against a cue-driven effect is that the authors found no interaction with time in the cue-locked data, whereas they did find such an interaction in the saccade-locked data. However, the lack of significance in the cue-locked data but significance in the saccade-locked data is not strong evidence against a cue-driven influence. Statistically, there is no direct comparison here, and more importantly, with longer delays, the cue-locked data may also start to show a dip (this could potentially be tested by the authors if they have enough trials available to extend their cue-locked analysis further in time). Indeed, exogenous attention, that may have been automatically evoked by the spatial cue, is known to be transient and to eventually even reverse after a brief initial facilitation (see e.g., Klein TiCS, 2000).

Finally, the authors consistently refer to "endogenous" attention (starting at line 221) when addressing potential cue-driven attention confounds. However, because the cue is not predictive, but is a spatial cue that differs in a bottom-up manner between left and right cues, "exogenous" attention is a more likely confound here in my view. Specifically, the spatial cue may automatically trigger attention in the direction of the target location it points to (and such exogenous effects would be expected even for unpredictive cues).

(3) Benefit and cost, or just cost?

Line 151 states that no statistically significant benefit for the saccade target was found compared to the neutral baseline. Yet, the claim throughout the article is distinct, such as in line 159: "These results show that approximately 100 milliseconds before microsaccade onset, discrimination rapidly improved at the intended target location". I do not question the robustness of the congruency effect, but the authors should be more careful when inferring "improved" perception at the target location because, as far as I could tell (as well as in the authors' own writing in line 151), this is not substantiated statistically when compared to the neutral baseline.

Related to this point, in Figure 3B, it would be informative to also see the average performance in the neutral cue condition (for example, as a straight line as in some other figures). This would help to better appreciate the relative benefits and/or costs compared to the neutral condition, also in the time-resolved data.

(4) Statistical inference for the comparison between failed and non-failed trials

Currently, the lack of modulation in the failed saccade trials hinges on a null effect. It would be stronger to support the claims with a significant difference in the congruency effect between failed and non-failed trials. Indeed, lack of significance in failed saccade trials does by itself not constitute valid evidence that the congruency effect is larger in saccade compared to failed saccade trials. For this, a significant interaction between saccade-trial-type (failed/non-failed) and congruency (congruent/incongruent) should be established (see e.g., Nieuwenhuis et al., Nat Neurosci, 2011).

(5) Time window justification

While the authors nicely depict their data across the full time axis, all statistics are currently performed on data extracted from specific time windows. How exactly were these time windows determined and justified? Likewise, how were the specific times picked for visualizing and statistically quantifying the data in e.g., Figures 3D and E? It would be reassuring to add justification for these specific time windows and/or to verify (using follow-up analyses) that the presented results are robust when different time windows are chosen.

(6) Microsaccade definition

Microsaccades are explicitly defined as being below half a degree. This appears rather arbitrary and rigid. Does the size of saccades not ultimately depend on the task and stimulus (e.g., Otero-Millan et al., PNAS, 2013) rather than being a fixed biological property? Perhaps this could be stated less rigidly, such as by stating how microsaccades are often observed below 0.5 degrees.

(Relatedly, one may wonder whether the type of instructed saccades that the authors studied here involves the same type of eye movements as the type of fixational microsaccades that have been the focus of ample prior studies. However, I recognize that this specific reflection may open a debate that is beyond the scope of this article.

-

-

www.uproot.space www.uproot.space

-

Who owns the order of Black memory? The person who brought it to the White institution

Archives shift power and ownership of Black history to the White institutions and collectors, rather than the Black individuals and communities who originally lived and created those memories.

-

archives are institutions defining documentary history: the things within the archive are the facts and the things without are suspect

This shows how archives have the power to determine what is considered true. If something is included in an archive, it is treated as fact, but if it is not archived, people may questions its legitimacy even if it is real.

-

Here is a photo of a baptism, in a river a few minutes walk from my family homestead, cataloged: date, unknown; individuals, unknown; creator, unknown

Shows that archives lose important contextual knowledge, even when the originating community knows exactly who and what is represented.

-

“The neighborhood is an archive, the woman was an archive, this land is an archive.”

An archive records the context of time and particular experience

-

-

adatosystems.com adatosystems.com

-

BLOG: How NOT to Answer the Salary Question

- The article argues that answering the "What is your current/expected salary?" question with a single number is a strategic mistake that limits your earning potential.

- Giving a specific number early in the process creates an "anchor" that recruiters will use to keep the offer as low as possible.

- Instead of providing a number, the author suggests pivoting the conversation toward the value you bring to the role and the total compensation package.

- A key strategy is to ask for the company's budgeted range for the position first, which puts the onus on the employer to disclose their limits.

- If forced to give a range, ensure the bottom of your range is the minimum you would actually accept, while the top represents your "dream" scenario.

- The goal of salary discussions in early interviews should be to establish "alignment" rather than a final price tag.

- Delaying the specific salary talk until after you have "wowed" the team gives you more leverage, as they are now invested in hiring you specifically.

Hacker News Discussion

- Many commenters emphasize that while "not answering" is a common piece of advice, it can be impractical for those who lack extreme leverage or are in urgent need of work.

- A popular counter-strategy mentioned is to confirm the salary range during the very first recruiter call to avoid wasting hours on interviews for a role that cannot meet your financial requirements.

- Users suggested that if you do provide a number first, you should always include a disclaimer that you "look at the entire package holistically" (benefits, equity, PTO) to maintain flexibility for later negotiation.

- There is a consensus that once a final offer is made, you should almost always ask, "Is there any way you can come up a little bit from that?" as this simple question frequently results in a 5-10% bump with minimal risk.

- Some participants shared "pleasant surprise" stories where refusing to name a price led to offers significantly higher (+50% or more) than what they would have asked for.

- The discussion highlights a shift toward transparency, with many noting that asking for the "salary band" is becoming a standard and respected practice in tech hiring.

-

-

library.oapen.org library.oapen.org

-

What about engaging in a virtual game world where you can have a conversation with a character that knows you and your backstory?

Hmmm intriguing and somewhat creepy at the same time.

-

spending time engaging in popular games such as Minecraft or Fortnitemay foster an appreciation of exciting experiences in high-fidelity immersive

Note to self.

-

Online reading needs to be supported by other cognitive skills such as cyber-safe skills and relatedly, internet cognition: that is, accurate conceptions of the internet (Edwards et al., 2018).

When collecting COTR data students didn't have an accurate conception of the internet.

-

-

www.americanyawp.com www.americanyawp.com

-

Are burst, and Freedom rules the rescued land, —

used in a weird way

-

the fear of man which bringeth a snare,

unfamiliar

-

-

socialsci.libretexts.org socialsci.libretexts.org

-

Anthropologists are quick to put dates on our existence in North America because of their colonized mindset to attempt to "prove" we have no history or "not enough" history in our homelands to lay claim to it. By trying to date our existence closer to the invasion of the Americas, they are attempting to dismiss our connection to our place of origin and our creation.

after reading this paragraph it remain me of the history they told us in elementary about Europeans being tht goos guys in the stories.

-

-

-

tags: [] source: https://www.nytimes.com/2026/02/16/movies/robert-duvall-dead.html author: Clyde Haberman

Robert Duvall, ‘Godfather’ and ‘Apocalypse Now’ Actor, Dies at 95<br /> by [[Clyde Haberman]] in The New York Times<br /> accessed on 2026-02-17T08:25:34

-

From early on, Mr. Duvall enjoyed the life of a supporting actor. “Somebody once said that the best life in the world is the life of a second leading man,” Mr. Duvall told The Times. “You travel, you get a per diem, and you’ve probably got a better part anyway. And you don’t have the weight of the entire movie on your shoulders.”

-

Even as a boy, in a Navy family that moved around the country, he had an ear for people’s speech patterns and an eye for their mannerisms. “I hang around a guy’s memories,” he once said. Insights that he gleaned were routinely tucked away in his head for potential future use.

-

-

human.libretexts.org human.libretexts.org

-

Based on the reading above, what does “tener” mean?

to have

-

ellos/ellas/ustedes:

tienen

-

nosotros:

tenemos

-

él/ella/usted:

tiene

-

Tú:

tienes

-

Yo

tengo

-

-

human.libretexts.org human.libretexts.org

-

Compro (I buy) un libro en ____________.

Compro un libro en la librería.

-

El fútbol de mesa está en ____________.

El fútbol de mesa está en la sala de juegos.

-

El escenario está en ____________.

El escenario está en el teatro.

-

La comida está en ____________.

Una cama está en el dormitorio.

-

Una cama está en ____________.

Una cama está en el dormitorio.

-

Los libros antiguos están en ____________.

Los libros antiguos están en la biblioteca.

-

Las pesas están en ____________.

Las pesas están en el gimnasio.

-

El vaso de precipitado está en ____________.

El vaso de precipitado está en el laboratorio.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

eLife Assessment

This important study identifies a novel role for Hes5+ astrocytes in modulating the activity of descending pain-inhibitory noradrenergic neurons from the locus coeruleus during stress-induced pain facilitation. The role of glia in modulating neurological circuits including pain is poorly understood, and in that light, the role of Hes5+ astrocytes in this circuit is a key finding with broader potential impacts. This work is supported by convincing evidence, albeit somewhat limited by the indirect nature of the evidence linking adenosine to nearby neuronal modulation, and possible questions on the population specificity of the transgenic approach.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Review of the revised submission:

I thank the authors for their detailed consideration of my comments and for the additional data, analyses, and clarifications they have incorporated. The new behavioral experiments, quantification of targeted manipulations, and expanded methodological details strengthen the manuscript and address many of my initial concerns. While some questions remain for future work, the authors' careful responses and the additional evidence provided help resolve the main issues I raised, and I am generally satisfied with the revisions.

Review of original submission:

Summary

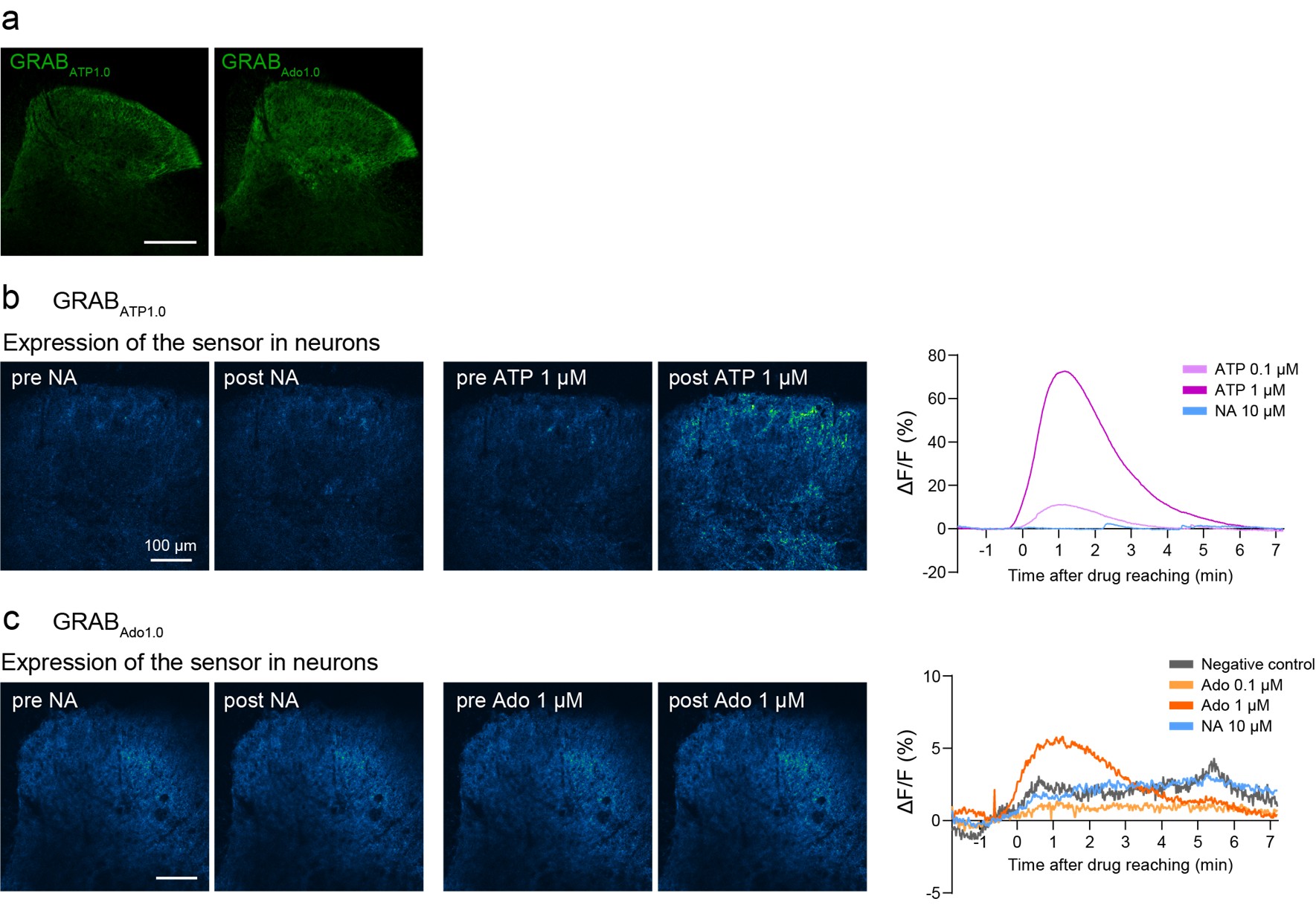

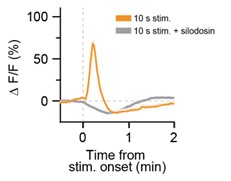

In this article, Kawanabe-Kobayashi et al., aim to examine the mechanisms by which stress can modulate pain in mice. They focus on the contribution of noradrenergic neurons (NA) of the locus coeruleus (LC). The authors use acute restraint stress as a stress paradigm and found that following one hour of restraint stress mice display mechanical hypersensitivity. They show that restraint stress causes the activation of LC NA neurons and the release of NA in the spinal cord dorsal horn (SDH). They then examine the spinal mechanisms by which LC→SDH NA produces mechanical hypersensitivity. The authors provide evidence that NA can act on alphaA1Rs expressed by a class of astrocytes defined by the expression of Hes (Hes+). Furthermore, they found that NA, presumably through astrocytic release of ATP following NA action on alphaA1Rs Hes+ astrocytes, can cause an adenosine-mediated inhibition of SDH inhibitory interneurons. They propose that this disinhibition mechanism could explain how restraint stress can cause the mechanical hypersensitivity they measured in their behavioral experiments.

Strengths:

(1) Significance. Stress profoundly influences pain perception; resolving the mechanisms by which stress alters nociception in rodents may explain the well-known phenomenon of stress-induced analgesia and/or facilitate the development of therapies to mitigate the negative consequences of chronic stress on chronic pain.

(2) Novelty. The authors' findings reveal a crucial contribution of Hes+ spinal astrocytes in the modulation of pain thresholds during stress.

(3) Techniques. This study combines multiple approaches to dissect circuit, cellular, and molecular mechanisms including optical recordings of neural and astrocytic Ca2+ activity in behaving mice, intersectional genetic strategies, cell ablation, optogenetics, chemogenetics, CRISPR-based gene knockdown, slice electrophysiology, and behavior.

Weaknesses:

(1) Mouse model of stress. Although chronic stress can increase sensitivity to somatosensory stimuli and contribute to hyperalgesia and anhedonia, particularly in the context of chronic pain states, acute stress is well known to produce analgesia in humans and rodents. The experimental design used by the authors consists of a single one-hour session of restraint stress followed by 30 min to one hour of habituation and measurement of cutaneous mechanical sensitivity with von Frey filaments. This acute stress behavioral paradigm corresponds to the conditions in which the clinical phenomenon of stress-induced analgesia is observed in humans, as well as in animal models. Surprisingly, however, the authors measured that this acute stressor produced hypersensitivity rather than antinociception. This discrepancy is significant and requires further investigation.

(2) Specifically, is the hypersensitivity to mechanical stimulation also observed in response to heat or cold on a hotplate or coldplate?

(3) Using other stress models, such as a forced swim, do the authors also observe acute stress-induced hypersensitivity instead of stress-induced antinociception?

(4) Measurement of stress hormones in blood would provide an objective measure of the stress of the animals.

(5) Results:

(a) Optical recordings of Ca2+ activity in behaving rodents are particularly useful to investigate the relationship between Ca2+ dynamics and the behaviors displayed by rodents.

(b) The authors report an increase in Ca2+ events in LC NA neurons during restraint stress: Did mice display specific behaviors at the time these Ca2+ events were observed such as movements to escape or orofacial behaviors including head movements or whisking?

(c) Additionally, are similar increases in Ca2+ events in LC NA neurons observed during other stressful behavioral paradigms versus non-stressful paradigms?

(d) Neuronal ablation to reveal the function of a cell population.

(e) The proportion of LC NA neurons and LC→SDH NA neurons expressing DTR-GFP and ablated should be quantified (Figures 1G and J) to validate the methods and permit interpretation of the behavioral data (Figures 1H and K). Importantly, the nocifensive responses and behavior of these mice in other pain assays in the absence of stress (e.g., hotplate) and a few standard assays (open field, rotarod, elevated plus maze) would help determine the consequences of cell ablation on processing of nociceptive information and general behavior.

(f) Confirmation of LC NA neuron function with other methods that alter neuronal excitability or neurotransmission instead of destroying the circuit investigated, such as chemogenetics or chemogenetics, would greatly strengthen the findings. Optogenetics is used in Figure 1M, N but excitation of LC→SDH NA neuron terminals is tested instead of inhibition (to mimic ablation), and in naïve mice instead of stressed mice.

(g) Alpha1Ars. The authors noted that "Adra1a mRNA is also expressed in INs in the SDH".

(h) The authors should comprehensively indicate what other cell types present in the spinal cord and neurons projecting to the spinal cord express alpha1Ars and what is the relative expression level of alpha1Ars in these different cell types.

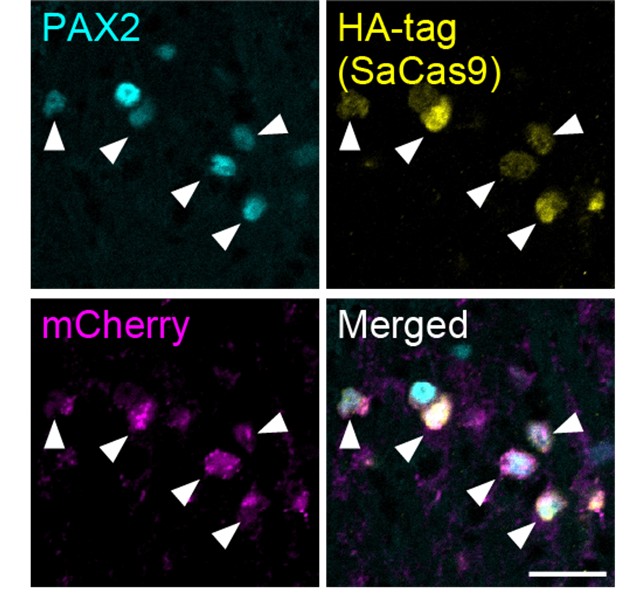

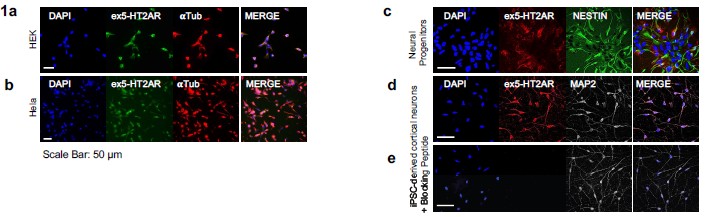

(i) The conditional KO of alpha1Ars specifically in Hes5+ astrocytes and not in other cell types expressing alpha1Ars should be quantified and validated (Figure 2H).

(j) Depolarization of SDH inhibitory interneurons by NA (Figure 3). The authors' bath applied NA, which presumably activates all NA receptors present in the preparation.

k) The authors' model (Figure 4H) implies that NA released by LC→SDH NA neurons leads to the inhibition of SDH inhibitory interneurons by NA. In other experiments (Figure 1L, Figure 2A), the authors used optogenetics to promote the release of endogenous NA in SDH by LC→SDH NA neurons. This approach would investigate the function of NA endogenously released by LC NA neurons at presynaptic terminals in the SDH and at physiological concentrations and would test the model more convincingly compared to the bath application of NA.

(l) As for other experiments, the proportion of Hes+ astrocytes that express hM3Dq, and the absence of expression in other cells, should be quantified and validated to interpret behavioral data.

(m) Showing that the effect of CNO is dose-dependent would strengthen the authors' findings.

(n) The proportion of SG neurons for which CNO bath application resulted in a reduction in recorded sIPSCs is not clear.

(o) A1Rs. The specific expression of Cas9 and guide RNAs, and the specific KD of A1Rs, in inhibitory interneurons but not in other cell types expressing A1Rs should be quantified and validated.

(6) Methods:

It is unclear how fiber photometry is performed using "optic cannula" during restraint stress while mice are in a 50ml falcon tube (as shown in Figure 1A).

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This study investigates the role of spinal astrocytes in mediating stress-induced pain hypersensitivity, focusing on the LC (locus coeruleus)-to-SDH (spinal dorsal horn) circuit and its mechanisms. The authors aimed to delineate how LC activity contributes to spinal astrocytic activation under stress conditions, explore the role of noradrenaline (NA) signaling in this process, and identify the downstream astrocytic mechanisms that influence pain hypersensitivity.

The authors provide strong evidence that 1-hour restraint stress-induced pain hypersensitivity involves the LC-to-SDH circuit, where NA triggers astrocytic calcium activity via alpha1a adrenoceptors (alpha1aRs). Blockade of alpha1aRs on astrocytes-but not on Vgat-positive SDH neurons-reduced stress-induced pain hypersensitivity. These findings are rigorously supported by well-established behavioral models and advanced genetic techniques, uncovering the critical role of spinal astrocytes in modulating stress-induced pain.

However, the study's third aim-to establish a pathway from astrocyte alpha1aRs to adenosine-mediated inhibition of SDH-Vgat neurons-is less compelling. While pharmacological and behavioral evidence is intriguing, the ex vivo findings are indirect and lack a clear connection to the stress-induced pain model. Despite these limitations, the study advances our understanding of astrocyte-neuron interactions in stress-pain contexts and provides a strong foundation for future research into glial mechanisms in pain hypersensitivity.

Strengths:

The study is built on a robust experimental design using a validated 1-hour restraint stress model, providing a reliable framework to investigate stress-induced pain hypersensitivity. The authors utilized advanced genetic tools, including retrograde AAVs, optogenetics, chemogenetics, and subpopulation-specific knockouts, allowing precise manipulation and interrogation of the LC-SDH circuit and astrocytic roles in pain modulation. Clear evidence demonstrates that NA triggers astrocytic calcium activity via alpha1aRs, and blocking these receptors effectively reduces stress-induced pain hypersensitivity.

Weaknesses:

The study offers mainly indirect evidence for astrocyte-released adenosine acting on SDH-VGAT neurons. The potential contributions of astrocyte-derived D-serine and adenosine to different spinal neuron subtypes, as well as the transient "dip" in astrocytic calcium following LC optostimulation, merit further clarification in future work once appropriate tools become available.

Comments on revisions:

The authors have thoroughly addressed my previous comments, resolving most of the points I raised except those noted in the "Weaknesses" section above. I understand that some of these aspects will require future tool development.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary

This is an exciting and timely study addressing the role of descending noradrenergic systems in nocifensive responses. While it is well-established that spinally released noradrenaline (aka norepinephrine) generally acts as an inhibitory factor in spinal sensory processing, this system is highly complex. Descending projections from the A6 (locus coeruleus, LC) and the A5 regions typically modulate spinal sensory processing and reduce pain behaviours, but certain subpopulations of LC neurons have been shown to mediate pronociceptive effects, such as those projecting to the prefrontal cortex (Hirshberg et al., PMID: 29027903).

The study proposes that descending cerulean noradrenergic neurons potentiate touch sensation via alpha-1 adrenoceptors on Hes5+ spinal astrocytes, contributing to mechanical hyperalgesia. This finding is consistent with prior work from the same group (dd et al., PMID:). However, caution is needed when generalising about LC projections, as the locus coeruleus is functionally diverse, with differences in targets, neurotransmitter co-release, and behavioural effects. Specifying the subpopulations of LC neurons involved would significantly enhance the impact and interpretability of the findings.

Strengths

The study employs state-of-the-art molecular, genetic, and neurophysiological methods, including precise CRISPR and optogenetic targeting, to investigate the role of Hes5+ astrocytes. This approach is elegant and highlights the often-overlooked contribution of astrocytes in spinal sensory gating. The data convincingly support the role of Hes5+ astrocytes as regulators of touch sensation, coordinated by brain-derived noradrenaline in the spinal dorsal horn, opening new avenues for research into pain and touch modulation.

Furthermore, the data support a model in which superficial dorsal horn (SDH) Hes5+ astrocytes act as non-neuronal gating cells for brain-derived noradrenergic (NA) signalling through their interaction with substantia gelatinosa inhibitory interneurons. Locally released adenosine from NA-stimulated Hes5+ astrocytes, following acute restraint stress, may suppress the function of SDH-Vgat+ inhibitory interneurons, resulting in mechanical pain hypersensitivity. However, the spatially restricted neuron-astrocyte communication underlying this mechanism requires further investigation in future studies.

Comments on revisions:

One important point remains insufficiently resolved. In Figure S4C, two of the three visible neurons in the A5 example appear to show a white "halo" at the cell border, suggesting a merge of eGFP (green) and TH (magenta) and therefore possible transgene positivity. To draw a confident conclusion about the specificity of the approach for the A6 (LC) population, the authors are kindly asked to provide high-resolution images of several representative A5 sections, presented both as merged and as separate colour channels. Ideally, quantification across multiple rostrocaudal sections of A5, A6 and A7 should be provided. This is essential for determining whether any transgene expression occurs within the A5 nucleus, particularly given its several-millimetre rostrocaudal extent. As the behavioural phenotype arises from manipulation of only a small subset of A6 neurons, ruling out any contribution from A5 (or A7) is critical for validating pathway specificity, especially in light of prior reports showing that similar approaches can label A5 fibres.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this article, Kawanabe-Kobayashi et al., aim to examine the mechanisms by which stress can modulate pain in mice. They focus on the contribution of noradrenergic neurons (NA) of the locus coeruleus (LC). The authors use acute restraint stress as a stress paradigm and found that following one hour of restraint stress mice display mechanical hypersensitivity. They show that restraint stress causes the activation of LC NA neurons and the release of NA in the spinal cord dorsal horn (SDH). They then examine the spinal mechanisms by which LC→SDH NA produces mechanical hypersensitivity. The authors provide evidence that NA can act on alphaA1Rs expressed by a class of astrocytes defined by the expression of Hes (Hes+). Furthermore, they found that NA, presumably through astrocytic release of ATP following NA action on alphaA1Rs Hes+ astrocytes, can cause an adenosine-mediated inhibition of SDH inhibitory interneurons. They propose that this disinhibition mechanism could explain how restraint stress can cause the mechanical hypersensitivity they measured in their behavioral experiments.

Strengths:

(1) Significance. Stress profoundly influences pain perception; resolving the mechanisms by which stress alters nociception in rodents may explain the well-known phenomenon of stress-induced analgesia and/or facilitate the development of therapies to mitigate the negative consequences of chronic stress on chronic pain.

(2) Novelty. The authors' findings reveal a crucial contribution of Hes+ spinal astrocytes in the modulation of pain thresholds during stress.

(3) Techniques. This study combines multiple approaches to dissect circuit, cellular, and molecular mechanisms including optical recordings of neural and astrocytic Ca2+ activity in behaving mice, intersectional genetic strategies, cell ablation, optogenetics, chemogenetics, CRISPR-based gene knockdown, slice electrophysiology, and behavior.

Weaknesses:

(1) Mouse model of stress. Although chronic stress can increase sensitivity to somatosensory stimuli and contribute to hyperalgesia and anhedonia, particularly in the context of chronic pain states, acute stress is well known to produce analgesia in humans and rodents. The experimental design used by the authors consists of a single one-hour session of restraint stress followed by 30 min to one hour of habituation and measurement of cutaneous mechanical sensitivity with von Frey filaments. This acute stress behavioral paradigm corresponds to the conditions in which the clinical phenomenon of stress-induced analgesia is observed in humans, as well as in animal models. Surprisingly, however, the authors measured that this acute stressor produced hypersensitivity rather than antinociception. This discrepancy is significant and requires further investigation.

We thank the reviewer for evaluating our work and for highlighting both its strengths and weaknesses. As stated by the reviewer, numerous studies have reported acute stress-induced antinociception. However, as shown in a new additional table (Table S1) in which we have summarized previously published data using the acute restraint stress model employed in our present study, most studies reporting antinociceptive effects of acute restraint stress assessed behavioral responses to heat stimuli or formalin. This observation is consistent with the findings from our previous study (Uchiyama et al., Mol Brain, 2022 (PMID: 34980215)). The present study also confirms that acute restraint stress reduces behavioral responses to noxious heat (see also our response to Comment #2 below). In contrast to the robust and consistent antinociceptive effects observed with thermal stimuli, some studies evaluating behavioral responses to mechanical stimuli have reported stress-induced hypersensitivity (see Table S1), which aligns with our current findings. Taken together, these data support our original notion that the effects of acute stress on pain-related behaviors depend on several factors, including the nature, duration, and intensity of the stressor, as well as the sensory modality assessed in behavioral tests. We have incorporated this discussion and Table S1 into the revised manuscript (lines 344-353). Furthermore, we have slightly modified the text including the title, replacing "pain facilitation" with "mechanical pain hypersensitivity" to more accurately reflect our research focus and the conclusion of this study that LC<sup>→SDH</sup> NAergic signaling to spinal astrocytes is required for stress-induced mechanical pain hypersensitivity. Finally, while mouse models of stress could provide valuable insights, the clinical relevance of stress-induced mechanical pain hypersensitivity remains to be elucidated and requires further investigation. We hope these clarifications address your concerns.

(2) Specifically, is the hypersensitivity to mechanical stimulation also observed in response to heat or cold on a hotplate or coldplate?

Thank you for your important comment. We have now conducted additional behavioral experiments to assess responses to heat using the hot-plate test. We found that mice subjected to restraint stress did not exhibit behavioral hypersensitivity to heat stimuli; instead, they displayed antinociceptive responses (Figure S2; lines 95-98). These results are consistent with our previous findings (Uchiyama et al., Mol Brain, 2022 (PMID: 34980215)) as well as numerous other reports (Table S1).

(3) Using other stress models, such as a forced swim, do the authors also observe acute stress-induced hypersensitivity instead of stress-induced antinociception?

As suggested by the reviewer, we conducted a forced swim test. We found that mice subjected to forced swimming, which has been reported to produce analgesic effects on thermal stimuli (Contet et al., Neuropsychopharmacology, 2006 (PMID: 16237385)), did not exhibit any changes in mechanical pain hypersensitivity (Figure S2; lines 98-99). Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that mechanical pain sensitivity is enhanced by other stress models, such as exposure to an elevated open platform for 30 min (Kawabata et al., Neuroscience, 2023 (PMID: 37211084)). However, considering our data showing that changes in mechanosensory behavior induced by restraint stress depend on the duration of exposure (Figure S1), and that restraint stress also produced an antinociceptive effect on heat stimuli (Figure S2), stress-induced modulation of pain is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple factors, including the stress model, intensity, and duration, as well as the sensory modality used for behavioral testing (lines 100-103).

(4) Measurement of stress hormones in blood would provide an objective measure of the stress of the animals.

A previous study has demonstrated that plasma corticosterone levels—a stress hormone—are elevated following a 1-hour exposure to restraint stress in mice (Kim et al., Sci Rep, 2018 (PMID: 30104581)), using a stress protocol similar to that employed in our current study. We have included this information with citing this paper (lines 104-105).

(5) Results:

(a) Optical recordings of Ca2+ activity in behaving rodents are particularly useful to investigate the relationship between Ca2+ dynamics and the behaviors displayed by rodents.

In the optical recordings of Ca<sup>2+</sup> activity in LC neurons, we monitored mouse behavior during stress exposure. We have now included a video of this in the revised manuscript (video; lines 111-114).

(b) The authors report an increase in Ca2+ events in LC NA neurons during restraint stress: Did mice display specific behaviors at the time these Ca2+ events were observed such as movements to escape or orofacial behaviors including head movements or whisking?

By reanalyzing the temporal relationship between Ca<sup>2+</sup> events and mouse behavior during stress exposure, we found that the Ca<sup>2+</sup> transients and escape behaviors (struggling) occurred almost simultaneously (video). A similar temporal correlation is also observed in Ca<sup>2+</sup> responses in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Luchsinger et al., Nat Commun, 2021 (PMID: 34117229)). The video file has been included in the revised manuscript (video; lines 111-113, 552-553, 573-575).

Additionally, as described in the Methods section and shown in Figure S2 of the initial version (now Figure S3), non-specific signals or artifacts—such as those caused by head movements—were corrected (although such responses were minimal in our recordings).

(c) Additionally, are similar increases in Ca2+ events in LC NA neurons observed during other stressful behavioral paradigms versus non-stressful paradigms?

We appreciate the reviewer's valuable suggestion. Since the present, initial version of our manuscript focused on acute restraint stress, we did not measure Ca<sup>2+</sup> events in LC-NA neurons in other stress models, but a recent study has shown an increase in Ca<sup>2+</sup> responses in LC-NA neurons by social defeat stress (Seiriki et al., BioRxiv, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.03.07.641347v1).

(d) Neuronal ablation to reveal the function of a cell population.

This method has been widely used in numerous previous studies as an effective experimental approach to investigate the role of specific neuronal populations—including SDH-projecting LC-NA neurons (Ma et al., Brain Res, 2022 (PMID: 34929182); Kawanabe et al., Mol Brain, 2021 (PMID: 33971918))—in CNS function.

(e) The proportion of LC NA neurons and LC→SDH NA neurons expressing DTR-GFP and ablated should be quantified (Figures 1G and J) to validate the methods and permit interpretation of the behavioral data (Figures 1H and K). Importantly, the nocifensive responses and behavior of these mice in other pain assays in the absence of stress (e.g., hotplate) and a few standard assays (open field, rotarod, elevated plus maze) would help determine the consequences of cell ablation on processing of nociceptive information and general behavior.

As suggested, we conducted additional experiments to quantitatively analyze the number of LC<sup>→SDH</sup>-NA neurons. We used WT mice injected with AAVretro-Cre into the SDH (L4 segment) and AAV-FLEx[DTR-EGFP] into the LC. In these mice, 4.4% of total LC-NA neurons [positive for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)] expressed DTR-GFP, representing the LC<sup>→SDH</sup>-NA neuronal population (Figure S4; lines 126-127). Furthermore, treatment with DTX successfully ablated the DTR-expressing LC<sup>→SDH</sup>-NA neurons. Importantly, the neurons quantified in this analysis were specifically those projecting to the L4 segment of the SDH; therefore, the total number of SDH-projecting LC-NA neurons across all spinal segments is expected to be much higher.

We also performed the rotarod and paw-flick tests to assess motor function and thermal sensitivity following ablation of LC<sup>→SDH</sup>-NA neurons. No significant differences were observed between the ablated and control groups (Figure S5; lines 131-134), indicating that ablation of these neurons does not produce non-specific behavioral deficits in motor function or other sensory modalities.

(f) Confirmation of LC NA neuron function with other methods that alter neuronal excitability or neurotransmission instead of destroying the circuit investigated, such as chemogenetics or chemogenetics, would greatly strengthen the findings. Optogenetics is used in Figure 1M, N but excitation of LCLC<sup>→SDH</sup> NA neuron terminals is tested instead of inhibition (to mimic ablation), and in naïve mice instead of stressed mice.

We appreciate the reviewer’s comment. The optogenetic approach is useful for manipulating neuronal excitability; however, prolonged light illumination (> tens of seconds) can lead to undesirable tissue heating, ionic imbalance, and rebound spikes (Wiegert et al., Neuron, 2017 (PMID: 28772120)), making it difficult to apply in our experiments, in which mice are exposed to stress for 60 min. For this reason, we decided to employ the cell-ablation approach in stress experiments, as it is more suitable than optogenetic inhibition. In addition, as described in our response to weakness (1)-a) by Reviewer 3 (Public review), we have now demonstrated the specific expression of DTRs in NA neurons in the LC, but not in A5 or A7 (Figure S4; lines 127-128), confirming the specificity of LCLC<sup>→SDH</sup>-NAergic pathway targeting in our study. Chemogenetics represent another promising approach to further strengthen our findings on the role of LCLC<sup>→SDH</sup>-NA neurons, but this will be an important subject for future studies, as it will require extensive experiments to assess, for example, the effectiveness of chemogenetic inhibition of these neurons during 60 min of restraint stress, as well as optimization of key parameters (e.g., systemic DCZ doses).

(g) Alpha1Ars. The authors noted that "Adra1a mRNA is also expressed in INs in the SDH".

The expression of α<sub>1A</sub>Rs in inhibitory interneurons in the SDH is consistent with our previous findings (Uchiyama et al., Mol Brain, 2022 (PMID: 34980215)) as well as with scRNA-seq data (http://linnarssonlab.org/dorsalhorn/, Häring et al., Nat Neurosci, 2018 (PMID: 29686262)).

(h) The authors should comprehensively indicate what other cell types present in the spinal cord and neurons projecting to the spinal cord express alpha1Ars and what is the relative expression level of alpha1Ars in these different cell types.