Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The main goals of this study by Guan, Aflalo and colleagues were to examine the encoding scheme of populations of neurons in the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) of a person with paralysis while she attempted individual finger movements as part of a brain-computer interface task (BCI). They used these data to answer several questions:

1) Could they decode attempted finger movements from these data (building on this group's prior work decoding a variety of movements, including arm movements, from PPC)?

2) Is there evidence that the encoding scheme for these movements is similar to that of able-bodied individuals, which would argue that even after paralysis, this area is not reorganized and that the motor representations remain more or less stable after the injury?

3) Related to #2: is there beneficial remapping, such that neural correlates of attempted movements change to improve BCI performance over time?

4) Can looking at the interrelationship between different fingers' population firing rate patterns (one aspect of the encoding scheme) indicate whether the representation structure is similar to the statistics of natural finger use, a somatotopic organization (how close the fingers are to each other), or be uniformly different from one another (which would be advantageous for the BCI and connects to question #3)? Furthermore, does the best fit amongst these choices to the data change over the course of a movement, indicating a time-varying neural encoding structure or multiple overlapping processes?

The study is well-conducted and uses sound analysis methods, and is able to contribute some new knowledge related to all of the above questions. These are rare and precious data, given the relatively few people implanted with multielectrode arrays like the Utah arrays used in this study. Even more so when considering that to this reviewer's knowledge, no other group is recording from PPC, and this manuscript thus is the first look at the attempted finger moving encoding scheme in this part of human cortex .

An important caveat is that the representational similarity analysis (RDA) method and resulting representational dissimilarity matrix (RDM) that is the workhorse analysis/metric throughout the study is capturing a fairly specific question: which pairs of finger movements' neural correlates are more/less similar, and how does that pattern across the pairings compare to other datasets. There are other questions that one could ask with these data (and perhaps this group will in subsequent studies), which will provide additional information about the encoding; for example, how well does the population activity correlate with the kinematics, kinetics, and predicted sensory feedback that would accompany such movements in an able-bodied person?

What this study shows is that the RDMs from these PPC Utah array data are most similar to motor cortical RDMs based on a prior fMRI study. It's innovative to compare effectors' representational similarity across different recording modalities, but this apparent similarity should be interpreted in light of several limitations: 1) the vastly different spatial scales (voxels spanning cm that average activity of millions of neurons each versus a few mm of cortex with sparse sampling of individual neurons, 2) the vastly different temporal scales (firing rates versus blood flow), 3) that dramatically different encoding schemes and dynamics could still result in the same RDMs. As currently written, the study does not adequately caveat the relatively superficial and narrow similarity being made between these data and the prior Ejaz et al (2015) sensorimotor cortex fMRI results before except for (some) exposition in the Discussion.

Relatedly, the study would benefit from additional explanation for why the comparison is being made to able-bodied fMRI data, rather than similar intracortical neural recordings made in homologous areas of non-human primates (NHPs), which have been traditionally used as an animal model for vision-guided forelimb reaching. This group has an illustrious history of such macaque studies, which makes this omission more surprising.

A second area in which the manuscript in its current form could better set the context for its reader is in how it introduces their motivating question of "do paralyzed BCI users need to learn a fundamentally new skillset, or can they leverage their pre-injury motor repertoire". Until the Discussion, there is almost no mention of the many previous human BCI studies where high performance movement decoding was possible based on asking participants to attempt to make arm or hand movements (to just list a small number of the many such studies: Hochberg et al 2006 and 2012, Collinger et al 2013, Gilja et al 2015, Bouton et al 2016, Ajiboye*, Willett* et al 2017; Brandman et al 2018; Willett et al 2020; Flesher et al 2021). This is important; while most of these past studies examined motor (and somatosensory) cortex and not PPC (though this group's prior Aflalo*, Kellis* et al 2015 study did!), they all did show that motor representations remain at least distinct enough between movements to allow for decoding; were qualitatively similar to the able-bodied animal studies upon which that body of work was build; and could be readily engaged by the user just by attempting/imagining a movement. Thus, there was a very strong expectation going into this present study that the result would be that there would be a resemblance to able-bodied motor representational similarity. While explicitly making this connection is a meaningful contribution to the literature by the present study (and so is comparing it to different areas' representational similarity), care should be taken not to overstate the novelty of retained motor encoding schemes in people with paralysis, given the extensive prior work.

The final analyses in the manuscript are particularly interesting: they examine the representational structure as a function of a short sliding analysis window, which indicates that there is a more motoric representational structure at the start of the movement, followed by a more somatotopic structure. These analyses are a welcome expansion of the study scope to include the population dynamics, and provides clues as to the role of this activity / the computations this area is involved in throughout movement (e.g., the authors speculate the initial activity is an efference copy from motor cortex, and the later activity is a sensory-consequence model).

An interesting result in this study is that the participant did not improve performance at the task (and that the neural representations of each finger did not change to become more separable by the decoder). This was despite ample room for improvement (the performance was below 90% accuracy across 5 possible choices), at least not over 4,016 trials. The authors provide several possible explanations for this in the Discussion. Another possibility is that the nature of the task impeded learning because feedback was delayed until the end of the 1.5 second attempted movement period (at which time the participant was presented with text reporting which finger's movement was decoded). This is a very different discrete-and-delayed paradigm from the continuous control used in prior NHP BCI studies that showed motor learning (e.g., Sadtler et al 2014 and follow-ups; Vyas et al 2018 and follow-up; Ganguly & Carmena 2009 and follow-ups). It is possible that having continuous visual feedback about the BCI effector is more similar to the natural motor system (where there is consistent visual, as well as proprioceptive and somatosensory feedback about movements), and thus better engages motor adaptation/learning mechanisms.

Overall the study contributes to the state of knowledge about human PPC cortex and its neurophysiology even years after injury when a person attempts movements. The methods are sound, but are unlikely (in this reviewer's view) to be widely adopted by the community. Two specific contributions of this study are 1) that it provides an additional data point that motor representations are stable after injury, lowering the risk of BCI strategies based on PPC recording; and 2) that it starts the conversation about how to make deeper comparisons between able-bodied neural dynamics and those of people unable to make overt movements.

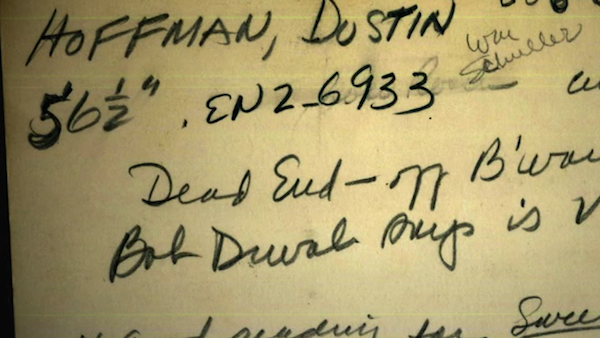

Screen capture from the movie

Screen capture from the movie