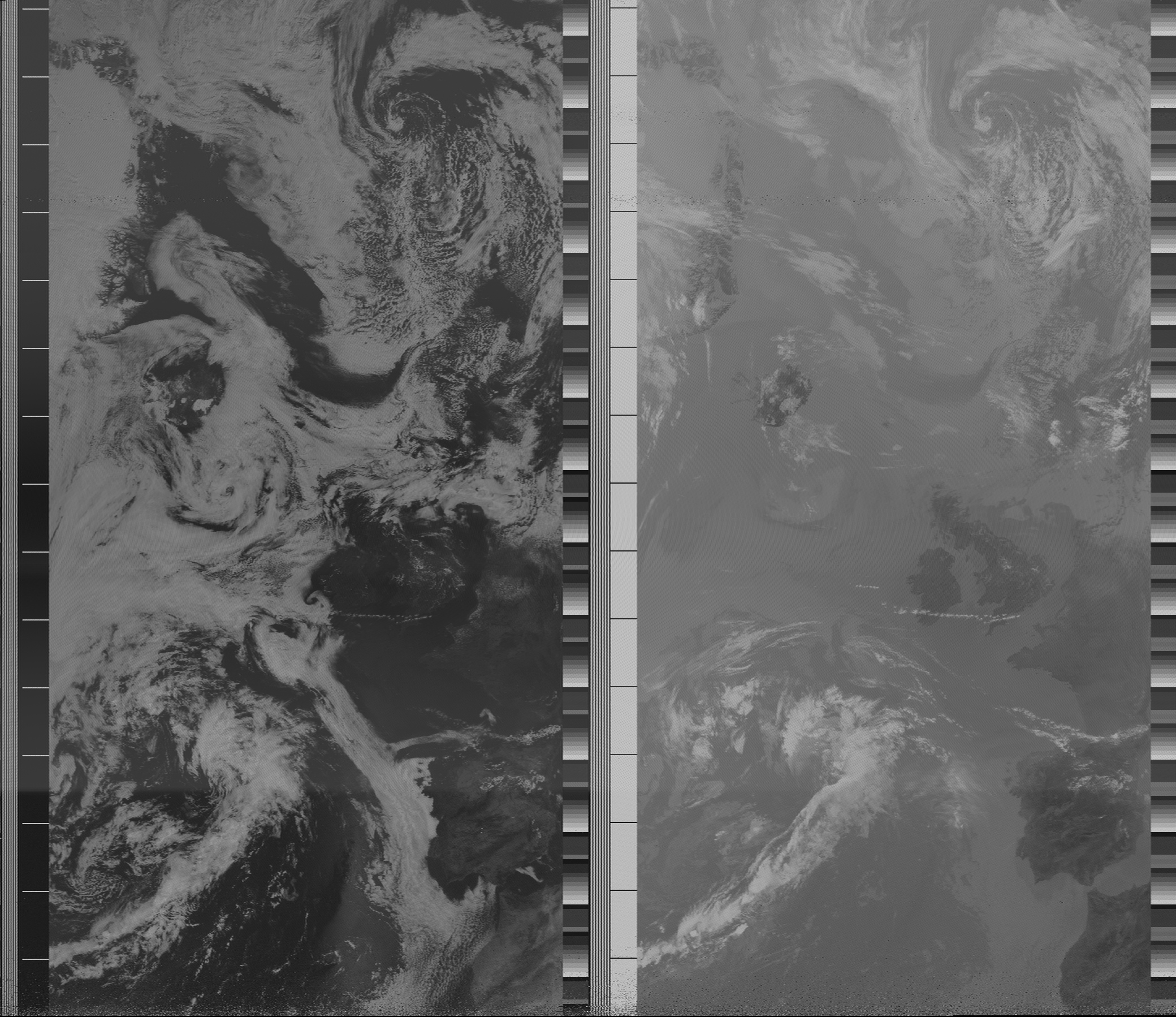

cosmogenesis

The most fundamental basis of the world was what Deleuze and Guattari strangely called “the Earth.” As a matter of fact, the latter was described as composed of “unformed, unstable matters, by flows in all directions, by free intensities or nomadic singularities, by mad or transitory particles.” It was “a body without organ,” which contained an infinite number of molecular and mobile quanta of matter and energy.

He [Professor Challenger] explained that the Earth—the Deterritorialized, the Glacial, the giant Molecule—[was] a body without organs. This body without organs [was] permeated by unformed, unstable matters, by flows in all directions, by free intensities or nomadic singularities, by mad or transitory particles. (A Thousand Plateaus, 1980, trans. B. Massumi, 1987, p. 40, my mod.)

At first, “the Earth” resembled the first steps of cosmogenesis in Morin’s narrative: the big bang projecting the first cloud of photons, the materializing of the first particles, their aggregation in simple nuclei then in atomic compounds. But it soon became clear to the reader that the “Earth” was considered the underlying reality even today. More than a first phase in the history of the world as reconstituted by modern cosmo-physics, it was a basic metaphysical datum concerning the part “before” the being becomes “actual” or “starts” to really exist under the various forms it actually takes, that is, what philosophers called its “virtual” part. This was Deleuze and Guattari’s manner to address the question of the “foundational crisis” that stroke philosophy with Nietzsche in the second half of the 19th century and mathematics in the early 20th century (Lapoujade, 2014, p. 31). The Earth was the virtual and self-disappearing foundation of all that existed.

Pascal Michon, "Double Articulation as Primary Form of Cosmological Stratification"