shocks

Ginsberg is, again, referring to Carl Soloman and electric shock therapy that mental hospitals, like Rockland, performed.

shocks

Ginsberg is, again, referring to Carl Soloman and electric shock therapy that mental hospitals, like Rockland, performed.

shocks of hospitals

Ginsberg is referring to Carl Soloman and electric shock therapy.

Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus

This is latin for, "Omnipotent, Eternal Father God."

Carl Solomon! I’m with you in Rockland

The solidarity here, that Ginsberg shares with Carl Solomon, the writer, in his stay at a mental institution is repeated throughout the third and final section. The impact of this refrain seems to speed up the already short lines and inject a hurried and excited tone in the finale.

Bellevue

Bellevue Hospital

Bellevue Hospital

yacketayakking

This is associated with lyrics from the song Yackety Yak by The Coasters. Famously and oft repeated are the lines, "Yackety Yak, don't talk back." The writer said of the song: it is "a white kid’s view of a black person’s conception of white society." This could just be the use of a colloquial phrase, or could be a comment on the meaning of the song as the writer describes it in relation to the framing Ginsberg is trying to convey.

III

The style of the poem changes drastically here. The lines are shorter, spaces are added, and there are noticeably fewer exclamation marks. In fact, in using ctrl+f, you can see almost exclusively that exclamation marks are used in the "moloch" section, specifically excluding the first line of Section III, "Carl Solomon!"

Moloch!

Moloch was a Semitic god, from an area that is now within Jordan, that is most known for requiring child sacrifice to worship. It seems Ginsberg is using Moloch as a metaphor for corruption in contemporary American societies, particularly in the case of consumerism and capitalism.

the madman bum and angel beat in Time

The character of bum is usually a pariah in society, a madman, as stereotyped by normal people. Yet here, the madman is beating a rhythm with an angel, a symbol of life and afterlife, and above all, sanctity.

maternal lamentation

Maternal lamentation could mean several different things depending on what reader is receiving it. It could be earthly, national, biblical even.

Firstly, as case of it being earthly, the world herself could be murmuring a sorrow for her children. Yet, the children of Earth are plenty more vocal than her. Why does she only murmur her lamentations, while they lie in agony, crying their pains? Why is she not in equal pain to the voices of the grass or of the nightingale? And, why is she so wracked with guilt, or sorrow, that she can only lament? Is it her own inaction at the force of a drought?

Firstly, as case of it being earthly, the world herself could be murmuring a sorrow for her children. Yet, the children of Earth are plenty more vocal than her. Why does she only murmur her lamentations, while they lie in agony, crying their pains? Why is she not in equal pain to the voices of the grass or of the nightingale? And, why is she so wracked with guilt, or sorrow, that she can only lament? Is it her own inaction at the force of a drought?

Secondly, in the context of the time this poem was written, maternal lamentation could also be speaking of Mother Country and the effects World War I had on both the land and the people. The personification of all earthly living things (grass, bats, birds) could be giving voice to all that perished. In the face of such loss, could it be that every little thing reminds survivors of the horrors of war? Then, in surviving, they can only lament and murmur against this. As is in the line 101, where the desert is filled and surrounded by " inviolable" voices of tragedy.

Secondly, in the context of the time this poem was written, maternal lamentation could also be speaking of Mother Country and the effects World War I had on both the land and the people. The personification of all earthly living things (grass, bats, birds) could be giving voice to all that perished. In the face of such loss, could it be that every little thing reminds survivors of the horrors of war? Then, in surviving, they can only lament and murmur against this. As is in the line 101, where the desert is filled and surrounded by " inviolable" voices of tragedy.

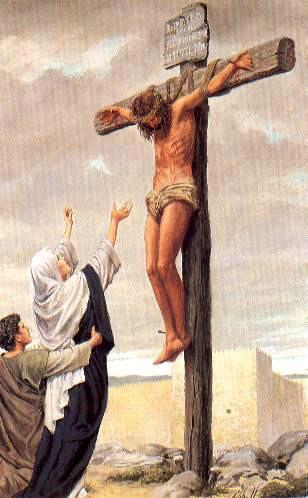

Lastly, maternal lamentation could refer to Virgin Mary's upset at her son's death. This seems most plausible, especially considering the general plot of rebirth and renew in spring and rains. In line 360, the stanza before this quote, the narrator ruminates, "Who is the third who walks always beside you? When I count, there are only you and I together." With religion in mind, it seems the other walking beside them would be Jesus. If this is the case, the ending of the poem could be about human kind's capability to be redeemed.

Lastly, maternal lamentation could refer to Virgin Mary's upset at her son's death. This seems most plausible, especially considering the general plot of rebirth and renew in spring and rains. In line 360, the stanza before this quote, the narrator ruminates, "Who is the third who walks always beside you? When I count, there are only you and I together." With religion in mind, it seems the other walking beside them would be Jesus. If this is the case, the ending of the poem could be about human kind's capability to be redeemed.

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata

Song: Maithreem Bhajat (Song meaning: Wiki)

The three D's (Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata), in Sanskrit, mean giving, compassion, and self-control. The title of this section is "What the Thunder Said." The thunder is telling the reader something, perhaps it is this: follow the guidelines of the three D's and redemption will come. These commanded virtues, juxtaposed with the rain that will surely come once the thunder has said what it came to say, seem to offer reprieve from the harshness of the previous sections of the poem. Either it's the calm before the storm or Eliot is giving the reader a chance at peace. In fact, shanti, in Indian, means bliss or peace, so perhaps it is bliss that will come. Either way, ending the poem in this way, using non-English, non-European language is very interesting. Eliot is giving voice to the other, yet it is still un-translated. Is there a reason why Eliot chose to not translate or elaborate these phrases from Hinduism? Indra is the Hindu thunder deity, he is an amalgam of Eastern and Western traditions, as he is modeled from Western gods, like Thor. In the same breath, Eliot is giving us what the thunder is saying, but deeper context still. After all, the sound of thunder only precedes the wash of rains.

So, to end the poem, Eliot gives three more Hindi prayers: Peace, Peace, Peace. And like that, whether soldiers from The Great War or survivors in its wake, beauty may come and bliss may be found. I think at this point, perhaps Eliot has renounced Christian faith or is open to others. This is shown throughout the poem, but in particular, lines 386-7, "Over the tumbled graves, about the chapel/There is the empty chapel, only the wind’s home." There is nothing in it for him, only graves to remind him of tragedy. Eliot may not only be giving voice to the other, but also becoming the other. We see right from the beginning, with the Greek, Latin, other languages throughout the poem, that Eliot is not translating these words, but he is heralding his own otherness by bringing these words to light. He's made them important. By ending the poem this way, I think Eliot is asserting these prayers seriously, with strictness and belief.

Bliss transcends awareness.

Bliss transcends awareness.

White devils with pitchforks Threw black devils on,

Whole poem is almost like a dark tale of warning. Interestingly, devils are portrayed as both white and black. If this is a poem about race, why did Brown choose to not make them distinctly different, despite having the white devils punish the black devils? It's kind of like Hughes' line, "human blood in human veins." It's like say, we're all the same, just on different ends of the pitchfork.

maternal lamentation

Mother Earth's lamentation, it seems, is that there is no water to save the hordes of voices crying out. She's murmuring though, while they scream in agony. This seems quite cold of her. Why is she not in equal pain to the song of the grass or the whistles of the bats? Why is she only murmuring, because she is weak (physically or otherwise)? Why is she so wracked with guilt, or is it sorrow? On the other hand and in the context of the time this poem was written, maternal lamentation could also be speaking of Mother Country and the effects World War I had on both the land and the people. The personification of all earthly living things (grass, bats, birds) could be giving voice to all that perished. In the face of such loss, could it be that every little thing reminds survivors of the horrors of war? Then, in surviving, they can only lament and murmur against the" inviolable" voices of tragedy surrounding them.

Hieronymo

Hieronimo/Hieronymo is the main character of Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy, a parody of Elizabethan plays of the time.

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. Shantih shantih shantih

The three D's, in Hindi, mean Giving, Compassion, and self-control. The title of this section is "What the Thunder Said." The thunder is telling the readers something, perhaps it is this: follow the guidelines of the three D's and redemption will come. Shanti, in Indian, means bliss, so perhaps it is bliss that will come. Either way, ending the poem in this way, using non-English, non-European language is very interesting. Eliot is giving voice to the other, yet it is still un-translated. Is there a reason why Eliot chose to not translate or elaborate these phrases from Hinduism? Indra is the Hindu thunder deity, he is an amalgam of Eastern and Western traditions, as he is modeled off of gods, like Thor. In the same breath, Eliot is giving us what the thunder is saying, but deeper context still. After all, the sound of thunder only precedes the wash of rains.

Bliss transcends awareness.

And dry grass singing

The motif of voice is exemplified here by the singing of the earth for water. This signifies a land in which nothing can grow. The grass is calling for its own redemption through its certain savior: water.

Dead

This poem, based on the title alone, is probably an elegy. This comes with it's own pre-set ideas of what's going to be discussed, like the "Rose" in Stein's piece. What is Eliot trying to give the reader with this title?

Mylae

I did a quick google search on this and it most likely refers to the Battle of Mylae. It was the first naval battle between two states and the First Punic War. What is the significance of Eliot using an ancient war in his poem?

I Tiresias have foresuffered

Foresuffered for being a woman for seven years?

glass

Is there a reason this stanza is rhymed so perfectly? Is she just going through the motions of life and so the poem is going through the motions of a, b, a, b.

music

The music mentioned here seems to follow in the following indentations. Particularly the "weialala leia"s and the "la la." The spell-like quality of these lines remind me of songs children sings that sometimes seem creepier on older ears. Yet this music (like the rats mentioned above) is creeping. Why is the music trying to sneak by the narrator, avoiding being heard?

Thank you.

Who is the narrator talking to? This line is followed by directions for the "thanked" to do. Yet this instructional-ism isn't continued. Why here?

place.

Place plays a huge role in this piece. Bringing it back to the theme of marriage, place means both the marriage home and the role of women in marriage (her place is in the home, kitchen, etc.) Because place is so confining and concrete, does the obscure form free the narrator of all constraints or highlight her wish to do so?

cheap jewelry and rich young men with fine eyes

They go around in their "gauds" (which is a homophone for Gods, interestingly enough) and are easily spotted as fake by young rich men. These women, young and hoping to find work for a family, have little hope to marry it seems.

Ring. Weigh pieces of pound.

Could this be weight of a lb./pound or of a £/pound? Either way, the weight of the ring, if it is an engagement or wedding band we're being given here, is either heavy in value or in weight (metaphorical weight?).

Push sea

Is this a homophone for pussy? Pussy usually refers to a cat, being weak, or a vagina. It is used most often in a derogatory fashion. Similarly, the previous line uses the word, "pet" which is often used (condescendingly) for women as a nickname. What sort of meaning do these lines, so close together, bring out?

Pussy

I don't think this particularly supports the "push sea" homophone, but it's interesting that it's here at the end. Just a small observation, but instead of next to pet, it's next to dog.

Nezars

A nezar is a Turkish amulet to protect you from the evil eye (a curse that will cause you harm or misfortune). Interestingly, they are shaped like the evil eye and sort of creepy in their own right. It's use in the poem, next to the oft repeated "neat," could mean several different things, or really nothing at all. I'm not knowledgeable in Turkish culture, so I'm not sure if there are similar words or phrases that are slipped into the poem. Maybe Stein is just conveying that protection is sometimes needed, or that ornamental things can be heavy too, etc. There really are so many different interpretations for this one word. Maybe the point is that there is no point of reference here.

I do

"I do" is repeated a few times in the poem, as is marriage. Is Stein talking about marriage in the poem? Is she talking about the roles men and women play in marriage?

death

moaning for release

alone

difficult hour

enduring to the end

He is drinking with himself, rather than by himself. There is mention of ghost, phantom, death in the poem, could it be that Flood has died, (maybe before Prohibition?) and is "pacing" outside of town, drinking as he ever would, lamenting about how few more moons he will see, how everyone he knows is gone and only strangers persist in their homes, and how he drinks in regret? Or is he perhaps the last one alive among his peers and loved ones?

gone so far to fill

1920 is when Prohibition began, as established by the 18th Amendment. Assuming the jug he is filling is full of alcohol (which though he does take a drink, has he filled it before the poem began or is it empty as he toasts with himself?) this would have to be an illegal act that he would do in the dead of night when the town was asleep. And in that case, if he were perhaps prone to drinking often before Prohibition, would he have then, once the ban on alcohol began, become a pariah on society, a stranger and hermit to all he called friends?

apparently thouht

Just to pose the question because it is repeated, and words are not often repeated without purpose in poetry:

The reader is guided alongside Eben's feelings and thoughts, especially those of fatigue and loneliness, in the piece, but why is it that things are "apparently" happening now, whereas things actively did in the beginning of the story? (i.e. "sat the jug down slowly at his feet with trembling care, knowing that most things break")

Also, *thought.

Eben Flood

Is the name Eben Flood an oronym, or homophone, for the words "ebb and flow?"

pretended

She doesn't seem to trust John at all. This marriage doesn't seem healthy. She seems to be feeling judged and treated like a burden.

I wonder if they all come out of that wall-paper as I did?

She identifies with the women in her fantasies. She has been jailed and now she's escaped, yet in the following line she says she is still tied by a rope. Her duality here, being free and imprisoned, even in her fantasy, is mirrored by her marriage.

He laughs at me

This doesn't seem like a happy marriage to me. John seems condescending, unwilling to hear her complaints or take into account any independent thoughts she might have. In the previous line she says that John must have never felt nervous in his life. I can almost hear a sarcastic tone here, like maybe this is a jab at John and his criticisms and lording over her.

occult

Why does Adams say all "mathematical problems of influence on human progress" are occult?

I think he is so overwhelmed by the newness of these scientific innovations and discoveries that he likens them to phenomena, or even magic. Like radium, which is a dangerous and very newly found metal, these particularly contemporary matters of math and science seem hard to grasp, concepts that might feel almost fabricated before his eyes. Perhaps he has such a respect for science, he feels the need to worship instead of understand?

b

In the opening line, Levine uses alliteration of the letter b. This gives the line a pattern, which is then carried over to the following line. These words (burlap, bearing butter, black bean, bread) call more attention to themselves. b is a voiced consonant, meaning your voicebox vibrates to pronounce it correctly, meaning they are already a letter we call attention to by voicing. I think this, right away, shows that Levine meant for the poem to be read aloud. This is only an opinion/observation.

From

And now, in the fifth and final stanza, the Levine brings the poem full circle. The reader gets a new anaphora, much like the first stanzas "out of" which is repeated at the beginning of each line. The "from" from the fourth stanza carries over, bleeds into, this stanza. The push and pull is over, the lion has come.

From

We get a new structure in the fourth stanza. Instead of "out of" or "come home," we get "from (something), come (something." The juxtaposition and repetition of from and come gives the reader a forceful push and pull, ebb and flow while reading.

calling in

Here, in the third stanza, we see the break of the repetition of "out of" and begin the "come" phase. There is a drawing in being repeated. Rather than the birth of the lion, we are hearing it being called, seeing it approach something.

Out of

"Out of" anaphora continues in the second stanza. The lion is still being created "out of" its industrialized surroundings.

Out of

Anaphora (best definition I can come up with: the repetition of a word/phrase at the beginning of line or phrase that creates a rhythm or emphasizes the words used) for "out of" begins wit the first line.