The epigraph to Eliot’s “The Wasteland,” written in Greek and Latin, is a quote from Petronius’ Satyricon, and reads (approximately) in English,

“I have seen with my own eyes the Sibyl hanging in a jar, and when the boys asked her ‘What do you want?’ She answered, ‘I want to die.’ ”

The tragic story of Cumaean Sibyl, a Greek prophetess, recounts the negotiation between Apollo and Sibyl, who bargained for immortality but made the mistake of neglecting to wish for eternal youth, and thus withered away for near eternity until she was small enough to live in a jar.

In this myth, Sibyl suffers a slow and painful exile that culminates in her caged isolation, her jar a constant reminder of her tragic mistake. In the case of Sibyl, eternal life is a kind of exile, for she has been banished to a thousand years of feeling herself deteriorate--by the time she is small enough to live hanging in a jar, she only wishes for death. In this instance, before the poem has even begun, Eliot presents exile as punishment, something so painfully isolating that it would drive a powerful, near-immortal prophetess like Sibyl to suicidal pleas. In the instance of Sibyl, exile is torment not just because she has become isolated from humanity, but because there is no foreseeable end. Figures like Sybil, Philomel, and Phlebas are not able to roam or wander the scorched earth; instead, they are tethered (temporally, spatially, existentially) to their exile, suspended within a nightmarish iteration of solitary confinement that demands for a reconsideration of values such as immortality and transformation.

Eliot has not yet begun to complicate his exploration of exile and its effects; here, he offers the image of a prophetess, a clairvoyant with access to the divine, begging for death after undergoing the torment of eternity. Later, with his other allusions to exile with figures like Philomel and Tiresias, Eliot indicates that there exists the possibility of redemption, even exaltation, coloring the experience of exile as something at once traumatizing and transformative.

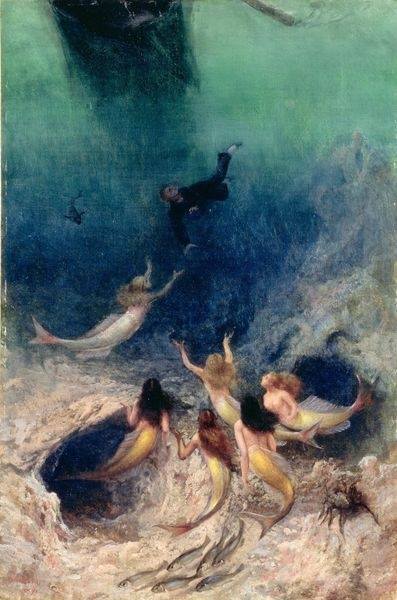

Within the context of "The Wasteland," Philomel exemplifies the exiled figure that recurs throughout the poem. Other notable figures of exile in “The Wasteland” include Tiresias (from “The Fire Sermon”), a blind prophet was was transformed into a woman for seven years; and Phlebas the Phoenician (from “Death by Water”), who dies and is exiled to the River Styx, where he “enters the whirlpool” of other mortals. What these particular figures of exile have in common is an experience of empowerment and transformation in their exile. Philomela, no longer a human, has the power of transfiguration; Tiresias, no longer a man, gains a particular understanding of both masculinity and femininity, a second sight no one else possesses; Phlebas, no longer alive, reflects on life from Styx and understands mortality, a knowledge one can only gain after experiencing death.

Within the context of "The Wasteland," Philomel exemplifies the exiled figure that recurs throughout the poem. Other notable figures of exile in “The Wasteland” include Tiresias (from “The Fire Sermon”), a blind prophet was was transformed into a woman for seven years; and Phlebas the Phoenician (from “Death by Water”), who dies and is exiled to the River Styx, where he “enters the whirlpool” of other mortals. What these particular figures of exile have in common is an experience of empowerment and transformation in their exile. Philomela, no longer a human, has the power of transfiguration; Tiresias, no longer a man, gains a particular understanding of both masculinity and femininity, a second sight no one else possesses; Phlebas, no longer alive, reflects on life from Styx and understands mortality, a knowledge one can only gain after experiencing death.