Here is Paula Freebird's Summary and Response to David Nye's essay, "Can we Define Technology"

. . .

Paula Freebird

“Can We Define Technology?” by David Nye

February 4, 2018

Summary

For this week's summary and response I have chosen to write about three themes in David Nye's essay: 1) tools and stories/language, 2) evolution of the word "technology'', and 3) technology and gender. Ney develops a unique theory about technology when he discusses how stories are almost "built in" tools. What does he mean by that? First, he compares the structure of stories — a situation, an encountered problem, a solution — to the structure in the invention of a tool. Whether by accident, or through planning, a tool comes into being when a problem is recognized within a situation, the solution is visualized, and then the tool is used. For Nye, thought process we go through when we invent, encounter, or use a tool involves the same thought process we go when we create stories. However, even if the structures are that same, Nye does not want us to think that we 'read" stories and tools in the same way. When we 'read' a tool we are in it and with it, using it in a practical way. Textual stories, on the other hand, are abstract, removed, and theoretical.

The evolution of the word "technology'', according to Nye, begins with the Greek word "techne". While the Greeks did not appreciate the manual work implied in the activity of "techne" (in other words, using tools for work) they nevertheless had a word for activity itself. The word seems to have disappeared for many centuries after the Greeks and only appears in the early 1800s (in the very early Industrial period) to refer, much like the Greeks, to specific skills (like "glassmaking" etc.) — or even more specifically to books (—logy) written about specific arts. In other words, the "technology of glassmaking" would refer to a book written about glassmaking.) As the Industrial period develops, Nye goes on to say, the word "only gradually came into circulation to the point where in the nineteenth century, institutions (like the Massachusetts institute of Technology) began to adopt the term. Broader use of the terms technologie and iechnikl in Germany led to their translation into the English technics in the twentieth century. Technology then becomes part of the professional definition of engineers. In a digression of the definition of the term, Lewis Mumford used the terms eotechnic, paleotechnic, and neotechnic to describe a chronology of technological development. While these terms are not used anymore, the word technology goes through several transformations in the twentieth century leading Nye to complain that "the meaning of "technology" remained unstable in the second half of the twentieth century, when it evolved into an annoyingly vague abstraction." Nye finally concludes that the word has finally stabilized to become "a comprehensive term for complex systems of machines and techniques."

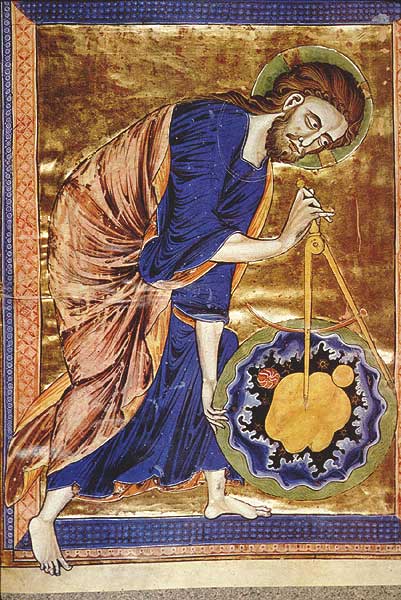

Nye only touches on the relationship between technology and gender towards the end of the essay. He acknowledges that, while Mumford contributed a lot to our thinking about technology, he (and presumably all other thinkers about technology at that time) "missed ... how thoroughly "technology" was shaped by gender." Nye backtracks to the medieval era to point out how deeply women were involved with trade and gives us examples, such as the making of ale, as being thoroughly controlled by women. It is only in the modern period that our perception of technology changes. Nye cites Ruth Oldenziel argument that Western society only relatively recently defined the word "technology" as masculine."

Response

Since the guiding question of this course is: “How does awareness of the history and philosophy of technology frame our relationship to technology?" I will focus my response to answering this question in relation to how I see my own thinking changing. It's only the beginning of the course, and this is only the first essay; still, i think the changing of my thinking might have already begun.

Regarding tools and stories, I am not sure whether I believe it or not. It seems to me to be a hit far¬fetched. I think Nye wants to somehow connect “language" with "tool making" — perhaps because he wants to show both as being deeply human traits. But I can't see any "story" in a tool. Even at the end of his argument, he says we don't read textual stories and tools in the same way. Of course. That's exactly what I mean. Maybe I can say I "use" stories (like to put my kids to sleep) the way I "use' a tool. Still, it is curious to me that this kind of far-fetched thinking can come up in the course of discussing technology. In that sense, my thinking about how technology “frames[s] our}my] relationship to technology" is being affected. While I do not have to accept everything I read, I have to think about it and try to say as clearly as I can "why” I do not accept it.

The historical evolution of the word "technology" brings to my mind a connection between "practice" and "theory". Practice is, well, practical. I don't need to know the name of the tool I am using to be able to use it. So, the fact that people (except for the Greeks who were —there is no other way, to say it — lazy because they had slaves) would not care about coming up with word like techne does not surprise me. They were busy using the tools. This makes me think the modern return to developing the word (technologie, technik, technique, technology, tech, etc.) may be part of a theorizing process we are in (lazy like the Greeks, I don't know...). Anyway, this relationship between practice and theory is probably a very important thing for me to think about in relation to my relationship to technology.

The topic of gender and technology, however, is really changing the way I think about technology. I don't have much to say about it right now (Nye does not give us much). But, hard as it may seem to believe, it seems to me to be critical to our understanding of technology. I’ll say this, until we figure out this relationship, we may never be able to get out of the technological quagmire we find ourselves in. There, I said it. It's a stab in the dark, but I think I will have more to say on this as I continue reading.