Author Response

Summary:

The strengths of the study are the findings that a single oxytocin level measured from saliva or plasma is not meaningful in the way that the field might currently be measuring. The reviewers appreciated this finding, and the careful attention to detail, but felt that the results fell short.

Reviewer #1:

This article describes the investigation of a valuable research question, given the interest in using salivary oxytocin measures as a proxy of oxytocin system activity. A strength of the study is the use of two independent datasets and the comparison between intranasal and intravenous administration. The authors report poor reliability for measuring salivary oxytocin across visits, that intravenous delivery does not increase concentrations, and that salivary and blood plasma concentrations are not correlated.

Line 77-78: While it's true that saliva collection provides logistical advantages, there are also measurement advantages (e.g., relatively clean matrix) that are summarised in the MacLean et al (2019) study, which has already been cited.

Thanks for the suggestion. We added this advantage:

Line 101 “Compared to blood sampling, saliva collection presents several logistical and measurement advantages (i.e. relatively clean matrix)(1).”

Line 86: It is important to note that the 1IU intravenous dose in this study led to equivalent concentrations in blood compared to intranasal administration.

The reviewer is right that 10 IU (over 10min) in our case increased the concentrations of plasmatic oxytocin beyond those observed for the spray or nebuliser (we reported the full time-course of variations in plasmatic oxytocin in another manuscript we published earlier this year)(2). This was an intentional aspect of our study design. We decided to use the highest intravenous dose (at the highest rate of 1IU/min) that we could get permission to administer safely in healthy volunteers as a proof of concept, so as to achieve a robust and prolonged increase in plasmatic oxytocin over the course of our full testing session. In this manner, we demonstrate that even when plasmatic levels of OT are maintained substantially increased throughout the observation interval, we cannot detect increases in salivary oxytocin. In this aspect, we believe that our manuscript goes one step beyond the important findings described in of Quintana et al. 2018(3), showing that this phenomenon is not linked to dosage (or to amount of increase in plasmatic levels of exogenous OT), as far as we can determine given the current safety standards for the administration of OT IV.

Please see also response to Reviewer 2, point 1.

Line 158: When using both ELISA and HPLC-MS, extracted and unextracted samples are correlated when measuring oxytocin concentrations in saliva, at least in dogs. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.08.033).

Thanks for pointing out this study. Indeed, in this specific study the authors found correlations between extracted and unextracted saliva samples. Such associations in humans have nevertheless been rare. In humans, the body of evidence suggests that the measurements obtained when comparing extracted samples to unextracted samples, or when comparing samples obtained using different methods of quantification (for instance, ELISA versus radioimmunoassay), do not correlate or show very low correlations (4, 5). Furthermore, most ELISA kits and HPLC-MS protocols to measure oxytocin have so far fallen short on sensitivity to detect the typical concentrations observed in humans at baseline (0-10pg/ml)(6). The current gold-standard method for quantifying oxytocin in biological fluids is the radioimmunoassay we used in this study(4). This method has shown superior sensitivity and specificity when compared to other quantification methods, when combined with extracted samples; therefore, it was our primary choice. We now highlight this advantage in the revised version of the manuscript more explicitly.

Line 129 “For all analyses, we followed current gold-standard practices in the field and assayed oxytocin concentrations using radioimmunoassay in extracted samples, which has shown superior sensitivity and specificity when compared to other quantification methods(7).”

Statistical reporting: I ran the article through statcheck R package (a web version is also available) and found a number of inconsistencies with the reported statistics and their p values. For example, on Line 302 the authors reported: t(123) = 1.54, p = 0.41, but this should yield a p value of 0.13. The authors should do the same and fix these errors.

Thanks very much for taking the time to check our statistical reporting thoroughly. We apologize if we were not sufficiently clear in the previous version of the manuscript, but the p-values we reported are corrected for multiple comparisons using Tukey correction. Currently, statcheck can only evaluate inconsistencies when the results are reported in the standard APA style and does not take into consideration corrections for multiple comparisons of any kind. We did check all of our statistical reporting and the p-values and correspondent statistics are correct (we only corrected an inadvertent error in reporting the degrees of freedom for these tests). In any case, we have now clarified in the manuscript when the reported p-values have been adjusted for multiple comparison to avoid any further confusion.

Line 305: The confidence intervals for these correlations should be reported.

We have now added the confidence intervals, estimated using bootstrapping, in our results section.

Line 348: This is an important point, but it's important to note that the vast majority of these studies use plasma or saliva measures. Perhaps CSF measures are more reliable, but the question wasn't assessed in the present study, and I'm not sure if anyone has looked at this question.

We are not aware of any study evaluating the stability of measurements of oxytocin in the CSF. Indeed, there are only a few studies sampling CSF to measure oxytocin in clinical patients and it is unlikely that CSF will become a widely used fluid to measure oxytocin in humans, given the invasiveness of the procedure to obtain CSF samples. Here, we wanted to refer specifically to saliva and plasma, which remain as the most popular options for measuring oxytocin in humans and which we investigated specifically in the current study. We have changed the text accordingly for clarity.

Line 466 “Our data poses questions about the interpretation of previous evidence seeking to associate single measurements of baseline oxytocin in saliva and plasma with individual differences in a range of neuro-behavioural or clinical traits.”

Line 423: I broadly agree with this conclusion, but it should be added that "single measurements of baseline levels of endogenous oxytocin in saliva and plasma are not stable under typical laboratory conditions" Perhaps these measures can be more stable using other means (i.e., better standardising collection conditions). But the fact remains, under typical conditions these measures do not demonstrate reliability.

Thanks for the suggestion. We have revised the text accordingly throughout the manuscript (examples below). Our study is a pharmacological study, which means that it is conducted in a highly controlled setting and adheres to strict protocols (i.e. we tested participants at the same time of the day, we instructed participants to abstain from alcohol and heavy exercise for 24 h and from any beverage or food for 2 h before scanning). These exclusion criteria were stricter than those applied in a large number of studies sampling saliva and plasma for measuring oxytocin for the purposes estimating possible associations with various traits associating. Most of these studies do not control, for instance, for fluid or food ingestion. Therefore, we expected our reliability calculations to represent an optimistic estimate of the reliabilities of the salivary and plasmatic oxytocin concentration used in most studies.

For now, it remains unclear to us what factors might be driving the within-subject variability in salivary and plasmatic concentrations we report in this study. Thanks to Reviewer 3, we are now confident that this is unlikely to represent measurement error (see response to Reviewer 3, point 3).

Line 117 “Here, we aimed to characterize the reliability of both salivary and plasmatic single measures of basal oxytocin in two independent datasets, to gain insight about their stability in typical laboratory conditions and their validity as trait markers for the physiology of the oxytocin system in humans.”

Line 567 “In summary, single measurements of baseline levels of endogenous oxytocin in saliva and plasma as obtained in typical laboratory conditions are not stable and therefore their validity as trait markers of the physiology of the oxytocin system is questionable.”

Reviewer #2:

Summary:

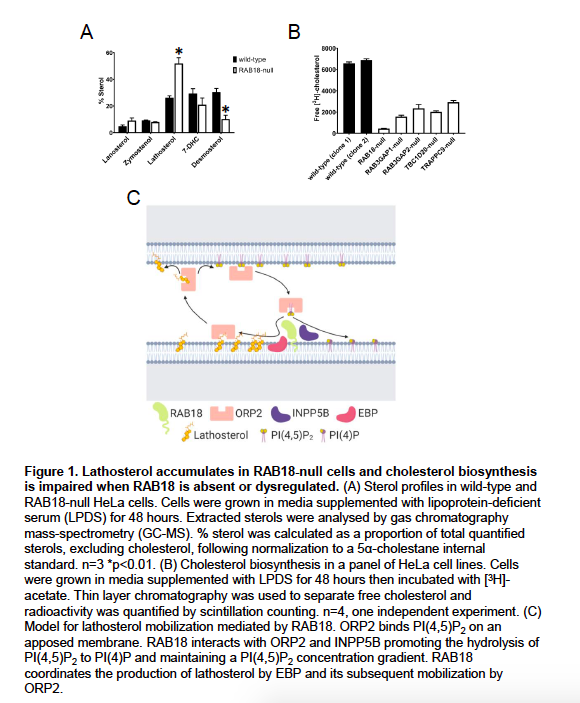

To test questions whether salivary and plasmatic oxytocin at baseline reflect the physiology of the oxytocin system, and whether salivary oxytocin index its plasma levels, the authors quantified baseline plasmatic and/or salivary oxytocin using radioimmunoassay from two independent datasets. Dataset A comprised 17 healthy men sampled on four occasions approximately at weekly intervals. In the dataset A, oxytocin was administered intravenously and intranasally in a triple dummy, within-subject, placebo-controlled design and compared baseline levels and the effects of routes of administration. With dataset A, whether salivary oxytocin can predict plasmatic oxytocin at baseline and after intranasal and intravenous administrations of oxytocin were also tested. Dataset B comprised baseline plasma oxytocin levels collected from 20 healthy men sampled on two separate occasions. In both datasets, single measurements of plasmatic and salivary oxytocin showed insufficient reliability across visits (Intra-class correlation coefficient: 0.23-0.80; mean CV: 31-63%). Salivary oxytocin was increased after intranasal administration of oxytocin (40 IU), but intravenous administration (10 IU) does not significantly change. Saliva and plasma oxytocin did not correlate at baseline or after administration of exogenous oxytocin (p>0.18). The authors suggest that the use of single measurements of baseline oxytocin concentrations in saliva and plasma as valid biomarkers of the physiology of the oxytocin system is questionable in men. Furthermore, they suggest that saliva oxytocin is a weak surrogate for plasma oxytocin and that the increases in saliva oxytocin observed after intranasal oxytocin most likely reflect unabsorbed peptide and should not be used to predict treatment effects.

General comments:

The current study tested research questions relevant for the study field. The analyses in two independent datasets with different routes of oxytocin administrations is the strength of current study. However, the limited novelty of findings and several limitations are noticed in the current report as described below.

Specific and major comments:

1) Previous study with similar results has already revealed that saliva oxytocin is a weak surrogate for plasmatic oxytocin, and increases in salivary oxytocin after the intranasal administration of exogenous oxytocin most likely represent drip-down transport from the nasal to the oral cavity and not systemic absorption (Quintana 2018 in Ref 13). Therefore, the novelty of current findings is limited. The authors should more clearly state the novelty of current results and the replication of previous findings.

We apologize for not describing the novelty and impact of our findings with sufficient clarity, and thanks for the opportunity to do so. Our study had two major goals. The first was to investigate whether single measurements of salivary and plasmatic concentrations of oxytocin can be reliably estimated within the same individual when collected at baseline conditions (i.e. without any experimental manipulation). As the reviewer highlighted, this is an important methodological question given the wide use of these measurements in a large and increasing number of studies to establish associations between the physiology of the oxytocin system and a number of brain and behavioural phenotypes in both clinical and non-clinical samples. However, to our knowledge, no previous study has appropriately conducted a thorough investigation of the reliability of these measurements (see also response to Reviewer 3, point 5). Thanks to our study, we now know that when single measurements are collected at baseline, salivary and plasmatic oxytocin cannot provide a sufficiently stable trait marker of the physiology of the oxytocin system in humans. As we highlight in the manuscript, this finding should deter the field from making strong claims based exclusively on associations of phenotypes with single measurements of peripheral oxytocin concentrations. Furthermore, our study also describes two very concrete implications of our findings which we believe are very important for the field. First, if baseline level of OT is to be used as a trait marker, future studies should, as much as possible, rely on repeated measures within the same participant but collected on different days to maximize reliability. Second, this less than perfect reliability should be taken into consideration when calculating the sizes of the samples needed to detect a certain effect, if it exists, with sufficient statistical power.

The second goal of our study was, as pointed out by the reviewer, to revisit the findings of Quintana et al. 2018(3), but this time with two major design modifications which could strengthen the conclusions from that study.

The first modification was the dose of intravenous oxytocin administered, which was considerably higher (see response to Reviewer 1, point 2). The administration of a higher dose that resulted in substantial and sustained increases in plasmatic oxytocin throughout the two hours observation period can only strengthen the previous conclusion that increases in plasmatic oxytocin cannot be detected in salivary measurements, and that this is not a matter of dose (as far as we can ascertain by administering the maximum intravenous dose we could safely administer in healthy volunteers). We believe that this is an important addition to the literature.

The second modification regarded the choice of the method we used to quantify oxytocin. In this study, we used radioimmunoassay, which is superior to ELISA in sensitivity and hence more appropriate to measure the low concentrations of oxytocin in saliva and plasma typically detected in humans at baseline conditions (1-10 pg/ml; for most individuals 1-5 pg/ml)(6). For instance, in Quintana et al. 2018(3) the limitations in the sensitivity of the ELISA kit used led the authors to discard around 50% of the collected saliva samples. Hence, our study replicates and extends the previous findings from Quintana et al. 2018 in important ways, demonstrating that the lack of an association between increases plasmatic oxytocin and salivary measurements is not limited by the dose of intravenous oxytocin administered or limitations of the sensitivity of the method used to quantify oxytocin.

We have now made the novelty and contribution of our work more explicit:

*Line 77 “Currently, we lack robust evidence that single measures of endogenous oxytocin in saliva and plasma at rest are stable enough to provide a valid trait marker of the activity of the oxytocin system in healthy individuals. Indeed, previous studies have claimed within-individual stability of baseline plasmatic and salivary concentrations of oxytocin in both adults and children based on moderate-to-strong correlations between salivary and plasmatic oxytocin concentrations measured repeatedly within the same individual over time using ELISA in unextracted samples(14-16). However, these studies have a number of methodological limitations that raise questions about the validity of their main conclusion that baseline plasmatic and salivary concentrations are stable within individuals. First, measuring oxytocin in unextracted samples has been postulated as potentially erroneous, given the high risk of contamination with immunoreactive products other than oxytocin(4). It is conceivable that these non-oxytocin immunoreactive products might constitute highly stable plasma housekeeping proteins (17) that masked the true variability in oxytocin concentrations. Second, a simple correlation analysis cannot provide information about the absolute agreement of two sets of measurements – which would be a more appropriate approach to study within-subject reliability/stability. Third, it is not clear whether these findings generalize beyond the early parenting(14) or early romantic(15) periods participants were in when the studies were conducted, since these periods engage the activity of the oxytocin system in particular ways(18). Hence, establishing the validity of salivary and plasmatic oxytocin as trait markers of the activity of the oxytocin system in humans remains as an unmet need. Such evidence is urgently required, given reports that plasma and saliva levels of oxytocin are frequently altered during neuropsychiatric illness and that they co-vary with clinical aspects of disease(13).”

Line 509 “Our findings were not consistent with these expectations. We could replicate previous evidence that intravenous oxytocin does not increase salivary oxytocin(3) and extended it by showing that the lack of increase in salivary oxytocin is not limited to the specific low dose of intravenous OT that was previously used (1IU) and that it is not driven by the insufficient sensitivity of the OT measurement method (which had resulted in more than 50% of the saliva samples being discarded in the previous study(3).”*

2) As authors discussed in the limitation section of discussion, the current study has several limitations such as analyses only in male participants and non-optimized timing of collection of saliva and blood due to the other experiments. These limitations are understandable, because the current study was the second analyses on the data of the other studies with the different aims. However, these limitations significantly limit the interpretations of the findings.

Here, we would like to highlight two aspects. First, most studies in the field are indeed conducted in men to avoid potential confounding from fluctuations in oxytocin concentrations across the menstrual cycle in women. Therefore, our study is representative of the typical samples used in most human studies. Second, we did not optimize our study to collect repeated samples of saliva. Indeed, it would have been interesting to describe the full-time course of variations of oxytocin concentrations in saliva after intranasal and intravenous administration. However, this does not detract the importance of our findings in respect to our first aim (which was our main goal).

We agree with the reviewer though that it is at least theoretically possible that we could have missed the window for increases in salivary oxytocin after intravenous oxytocin if it existed, given that we only sampled one post-administration time-point. However, we believe this was unlikely for one reason. Despite the sustained increase (throughout the two-hour observation interval) in plasmatic oxytocin following the intravenous administration of oxytocin, we observed no increase in salivary oxytocin post-dosing (at ~115 min). Unless the half-life of oxytocin is shorter in saliva than in the blood (which we do not know yet), we expected the levels of salivary oxytocin to mirror the changes in plasma – potentially with a slight delay given the time that it might take for oxytocin concentrations to build up in saliva through ultrafiltration from the blood, but this was not the case. Most likely the half-life of oxytocin in the saliva is not shorter than in the blood, since a previous study found increased concentrations of oxytocin in saliva up to 7h after administration of intranasal oxytocin (as the reviewer pointed out below, in our study we no longer could detect significant increases in plasmatic oxytocin after the intranasal administration of 40 IU with two different methods at around 115 mins post-administration). Therefore, while we acknowledge these limitations we also believe they do not detract from the importance of our main findings and the potential they hold to influence the field towards a more rigorous use of these measurements. Please see below for the implemented changes in the text.

Line 554 “It is possible that we may have missed peak increases in saliva oxytocin after the intravenous administration of exogenous oxytocin if they occurred between treatment administration and post-administration sampling. This is unlikely given that the dose we administered intravenously resulted in sustained increases in plasmatic oxytocin over the course of two hours. Unless the half-life of oxytocin in saliva is much shorter than in the plasma, it would be surprising to not find any increases in salivary oxytocin after intravenous oxytocin given that concentrations of oxytocin in the plasma were still elevated at the specific time-point of our second saliva sample. Currently, we have no estimate for the half-life of oxytocin in saliva; however, given that previous studies have found evidence of increased salivary oxytocin after single intranasal administrations of 16IU and 24IU oxytocin up to seven hours post-administration(19), it is unlikely that the half-life of oxytocin is shorter in the saliva than in the plasma.”

3) As reported in page 6, the dataset A comprises administrations approximately 40 IU of intranasal oxytocin and 10 IU on intravenous. The rationale to set these doses should be described. Since the 40IU is different from 24 IU which is employed in most of the previous publications in the research field, potential influence associated with the doses should be tested and discussed.

Thank you for the opportunity to clarify this aspect of our work. With respect of our primary aims (to investigate whether single measurements of salivary and plasmatic oxytocin at baseline can be reliably measured within individuals across different days), the choice of doses is of course not relevant.

With respect to our secondary aim, namely, to investigate whether salivary oxytocin can be used to index concentrations of oxytocin in the plasma, particularly after the administration of synthetic oxytocin using the intranasal and intravenous routes, the administered doses are relevant.

The data reported here were collected as part of a larger project – which determined the choice of both intranasal and IV doses (2). As explained in our response to Reviewer 1, point 2, the selection 10IU (over 10min) was the highest intravenous dose that we could get permission to administer safely in healthy volunteers as a proof of concept, so as to achieve a robust and prolonged increase in plasmatic oxytocin over the course of our full testing session. In this manner, we demonstrate that even when plasmatic levels of OT are maintained substantially increased throughout the observation interval, we cannot detect increases in salivary oxytocin.

Regarding the intranasal OT dose, it is worth noting that the 24 IU is indeed popular in oxytocin studies, but not exclusive, and generally the selection of dose in oxytocin studies has not been informed by detailed dose-response characterizations. Our choice of 40IU was made for the purposes of matching our previous work on the pharmacodynamics of OT in healthy volunteers(20), and is a dose we (21-29) and others (e.g. (30)) have commonly used with patients.

A potentially important implication if dose variations also imply variation in the total volume of liquid administered (as is usually the case with standard nasal sprays – but not with the nebuliser), then it is likely that the potential for drip-down might increase for higher volumes and decrease for lower volumes. As far as we know, no study has ever investigated the impact of administered volume on salivary oxytocin after the intranasal administration of synthetic oxytocin, but we agree this would be an important point to look at. We have now expanded our discussion to accommodate this point.

Line 519 “We expect this phenomenon to be particularly pronounced for higher administered volumes. Further studies should examine the impact of different administered volumes on increases in salivary oxytocin.”

4) It is difficult to understand that no significant elevations in plasma oxytocin levels were observed after intranasal spray or nebuliser of oxytocin. From figure 4A, the differences between levels at baseline and post administration are similar between nebuliser, spray, and placebo. Please discuss the potential interpretation on this result.

The plasmatic concentrations of oxytocin we report in this study refer solely to the samples acquired at around 2h after the administration of intranasal oxytocin. We reported the full-time course of changes in plasmatic oxytocin in a paper published earlier this year(2) – which we now refer the reader to. We did find increases in plasmatic oxytocin after administration of oxytocin with the spray and nebuliser (around 3x the baseline concentrations) that did not differ between intranasal methods of administration. Plasmatic oxytocin reached a peak within 15 mins from the end of the intranasal administrations. Given the short half-life of oxytocin in the plasma, we believe it is not surprising that at 115 mins after the end of our last treatment administration the concentrations of oxytocin in the plasma are no longer different from the placebo condition.

Line 166 “The full time course of changes in plasmatic oxytocin after the administration of intranasal and intravenous oxytocin in this study has been reported elsewhere(2).”

5) In page 12, the reason why not to employ any correction for multiple comparisons in the statistical analyses should be clarified.

We apologize that this was not sufficiently clear, but we did correct for multiple testing using the Tukey procedure in our analyses investigating the effects of treatment on salivary and plasmatic oxytocin (this was described in page 9 – Treatment effects). If the reviewer meant something else, we would be glad to follow any further advice on multiple testing correction he/she might have.

Line 250 “Treatment effects: The effect of treatment on blood/saliva oxytocin concentration were assessed using a 4 x 2 repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance Treatment (four levels: Spray, Nebuliser, Intravenous and Placebo) x Time (two levels: Baseline and post-administration). Post-hoc comparisons to clarify a significant interaction were corrected for multiple comparisons following the Tukey procedure.”

Reviewer #3:

In the current study, baseline samples of salivary and plasma oxytocin were assessed in 13, respectively, 16 participants, to assess intra-individual reliability across four time points (separated by approximately 8 days). The main results indicate that, while as a group, average salivary and plasma samples were not significantly different across time points, within-subject coefficient of variation (CV) and intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) showed poor absolute and relative reliability of plasma and salivary oxytocin measurements over time. Also no association was established between plasma and salivary levels, either at baseline or after administration of oxytocin (either intranasally, or intravenously). Further, salivary/ plasma oxytocin was only enhanced after intranasal, respectively intravenous administration.

The study addresses an important topic and the paper is clearly written. While the overall multi-session design seems solid, sample collections were performed in the context of larger projects and therefore there appear to be several limitations that reduce the robustness of the presented results and consequently the formulated conclusions.

General comments

1) A main conclusion of the current work is that 'single measures of baseline oxytocin concentrations in saliva and plasma are not stable within the same individual'. It seems however that the study did not adhere to a sufficiently rigorous approach to put forward this conclusion. It lacks a control for several important factors, such as timing of the day at which saliva/ plasma samples were obtained, as well as sample volume.

Particularly while it is indicated that all visits were identical in structure, important information is missing with regard to whether or not sampling took place consistently at a particular point of time each day, to minimize the influence of circadian rhythm. Without this information it is not possible to draw any firm conclusions on the nature of the intra-individual variability as demonstrated in the salivary and plasma sampling.

Thanks for pointing this out. Indeed, we were not sufficiently explicit on how strict we were in controlling for some potential sources of variability that could have contributed to the lack of reliability we report here. Our data was acquired in the context of two human pharmacological studies, which by design were strict on a number of aspects to minimize unwarranted noise. All participants were tested in the same period of the day (morning) to avoid the potential contribution of circadian fluctuations of oxytocin. In dataset A, we tried, as much as possible, to match the exact time participants were tested between visits, using the start time of the first visit as a reference. With the exception of one participant, where one session was conduct 1h and 30 mins later than the other three, all the remaining participants from study A were tested within 1h of the exact start time of session 1. Further, we also instructed participants to abstain from alcohol and heavy exercise for 24 h and from any beverage or food for 2 h before scanning. Hence, we believe our sampling protocol was strict enough to discard any potential contribution of major known sources of variability in oxytocin levels.

The reviewer also inquiries about the volume of the samples. For the plasma samples, we used a standardized protocol and collected the same blood volume in all participants, visits and time-points (1 EDTA tube of approximately 4 ml). The saliva samples were collected using Salivettes. Participants were instructed to place the swab from the Salivette kit in their mouth and chew it gently for 1 min to soak as much saliva as possible. After this, the swab was then returned back to the Salivette and centrifuged. In both cases, to avoid degradation of the peptide in the collected sample, we followed a strict protocol where all samples were put immediately in iced water until centrifugation, which happened within 20 mins of sample collection. Samples were then immediately stored at -80C until analysis. Hence, differences in degradation of the peptide related to the processing of the sample are also unlikely to justify the poor reliabilities we report here.

For completeness, we have now added all of these further details to our Methods section.

Line 169 “**All visits were conducted during the morning to avoid the potential confounding of circadian variations in oxytocin levels(31, 32). In addition, we also made sure that each participant was tested at approximately the same time across all four visits (all participants were tested in sessions with less than one hour difference in their onset time, except for one participant where the difference in the onset of one session compared to the other three sessions was 1.5h). “*

Line 192 “Blood was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid vacutainers (Kabe EDTA tubes 078001), placed in iced water and centrifuged at 1300 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C within 20 minutes of collection and then immediately pipetted into Eppendorf vials. Samples were immediately stored -80C until analysis. Saliva samples were collected using a salivette (Sarstedt 51.1534.500). Participants were instructed to place the swab from the Salivette kit in their mouth and chew it gently for 1 min to soak as much saliva as possible. After this, the swab was then returned back to the Salivette, centrifuged and stored in the same manner as blood samples. For both saliva and plasma, we stored the samples in aliquots of 0.5 ml, following the RIAgnosis standard operating procedures.

We followed this strict protocol, putting all samples in iced water until centrifugation with immediate storage at -80C until analysis to minimize the impact putative differences in degradation of the peptide related to differences in the processing of the samples might have on the reliability of the estimated concentrations of oxytocin.”

*

Correspondingly, a deeper discussion is needed on the reason why ICC's were considerably variable across pairs of assessment sessions, with some pairs yielding good reliability, whereas others yielded (very) poor reliability.

Currently we have no insightful hypothesis on why this could have been the case. Indeed, we found higher ICCs for only 2 out of 6 pairs of visits for the plasma. However, it is plausible that this might have occurred by chance. In any case, we should note that the 95% confidence intervals for the ICCs of our different pairs of samples overlap; this suggests that there is no evidence that the ICCs we estimated for the specific two pairs where we found higher reliabilities are significantly higher than those observed in the remaining pairs.

Line 431 “If there are specific reasons explaining the higher reliability indices observed for the specific pairs of sessions, these reasons remain to be elucidated. However, it is not implausible that we might have found higher reliabilities for these specific two pairs by chance, since the 95% confidence intervals for the ICCs for all pairs of samples overlapped.”

More detailed descriptions regarding sampling procedures (timing and sampling intervals) are necessary. Also, more information is needed on the volume of saliva collected at each session, to control for possible dilution effects.

This information has been added to the revised version of the manuscript (please see response to your point number 1). As a further clarification, oxytocin concentrations were measured in plasma and saliva aliquots of 0.5 ml, following the standard operating procedures of RIAgnosis. This volume was used for all participants, sessions and time-points. Furthermore, for measuring cortisol, the salivettes were shown to allow for an almost 100% recovery, regardless of cortisol concentration, volume of the sample or method of quantification(33), suggesting that the sampling method is robust.

2) It is indicated that the initial sample would allow to detect intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) of at least 0.70 (moderate reliability) with 80% of power. Is this still the case after the drop-outs/ outlier removals? Since the main conclusions of the work rely on negative results (conclusions drawn from failures to reject the null hypothesis) it is important to establish the risk for false negatives within a design that is possibly underpowered.

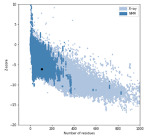

We understand the concern of the reviewer. However, according to the power calculations provided by Bujang and Baharum, 2017(34), the four repeated samples we collected in Dataset A would have allowed us to detect an ICC of 0.5 with 80% of statistical power even with only 13 subjects (which is the lowest sample size we used for the analysis on saliva in dataset A). The two samples we collected in Dataset B would allow us to detect an ICC of 0.6 with 80% of statistical power even with only 19 subjects. Hence, both datasets were powered to detect an ICC of 0.7 with acceptable power, if it existed, even after the exclusion of outliers.

3) Did the authors also assess within-session reliability? For example, by assessing ICC between pre and post-measurements in the placebo session.

Thanks for the suggestion. Indeed, we had not performed this analysis before but we agree it would be informative. We calculated the ICC and CV for the two samples acquired before any treatment administration and the intravenous infusion of saline during the placebo session. These samples where acquired with an approximate 15 min interval in between them. In this analysis, we found that the ICC was excellent 0.92 and the CV 20%. This additional analysis strengthens our findings by supporting the idea that our poor reliabilities across different days reflect true biological variability and cannot be attributed to measurement error. These new findings have now been included in the revised version of the manuscript.

Abstract

Line 44 "Results: Single measurements of plasmatic and salivary oxytocin showed poor reliability across visits in both datasets. The reliability was excellent when samples were collected within 15 minutes from each other in the placebo visit.”

Line 240 “Within-visit reliability analysis: To investigate the reliability of salivary and plasmatic oxytocin concentration within the same visit, we calculated the ICC and CV as described above for two samples acquired before any treatment administration and the intravenous infusion of saline during the placebo session. These samples where acquired with an approximate 15 minutes interval in between them.”

Line 405 “Furthermore, in a further analysis assessing the within-session stability of plasmatic oxytocin using two measurements collected 15 minutes apart from each other in the placebo visit (one sample collected at baseline and the other after the intravenous administration of saline), we found excellent within-session reliability (ICC=0.92, CV=20%). Together, this suggests that the low reliability of endogenous oxytocin measurements across visits in the current study results from true intrinsic individual biological variability and not technical variability/error in the method used for oxytocin quantification.“*

4) It is indicated that the intra-assay variability of the adopted radioimmunoassay constitutes <10%. Were analyses of the current study run on duplicate samples? Was intra-assay variability assessed directly within the current sample?

We reported the intra-assay variability determined by RIAgnosis during the development of this assay(35). This was not specifically assessed for the current study.

Introduction & Discussion

5) The introduction and discussion is missing a thorough overview of previous studies assessing intra-individual variability in oxytocin levels.

Thanks for the suggestion. We have now included in our introduction/discussion an overview of previous studies attempting to tackle this question, which unfortunately do not address this question with sufficient detail or using the appropriate methods and statistical analyses (see response to Reviewer 2, point 1). Hence, from the available evidence, it is not possible to draw robust conclusions about the validity of concentrations of oxytocin in saliva and plasma as valid trait markers of the activity of the oxytocin system. With this manuscript, we hope we can prompt further discussion and guide the field towards a more rigorous use of these measurements. A thorough discussion of this literature has now been added to the Introduction and Discussion.

Line 434 “Our observation of poor reliability questions the use of single measurements of baseline oxytocin concentrations in saliva and plasma as valid trait markers of the physiology of the oxytocin system in humans. Instead, we suggest that, at best, these measurements can provide reliable state markers within short time-intervals (5 mins in our study). Our data does not support previous claims of high stability of plasmatic and salivary oxytocin within individuals over time. For instance, in one study, Feldman et al. (2013) assessed plasmatic oxytocin in recent mothers and fathers at two time-points spaced six months apart during the postpartum period. The authors found strong correlations between the two assessments for both mothers and fathers(14). In another study, Schneiderman et al. (2012) found strong correlations between plasmatic oxytocin concentrations measured at two different instances spaced six months apart in both single and individuals recently involved in a new romantic relationship(15). Two important differences between these studies and ours are i) the method used for oxytocin quantification, and ii) the particular states participants were in when the studies were conducted. Regarding the first difference, these previous studies used ELISA without extraction, reporting concentrations of plasmatic oxytocin well above the typical physiological range of 1-10 pg/ml detected in extracted samples (in their studies, the authors report concentrations above 200 pg/ml). The inclusion of extraction has been postulated as a critical step for obtaining valid measures of oxytocin in biological fluids(4). Unextracted samples were shown to contain immunoreactive products other than oxytocin(4), which contribute largely to the concentrations of oxytocin estimated by this method. It is possible that these non-oxytocin products might represent highly stable plasma housekeeping molecules(17) that masked the true biological variability in oxytocin concentrations between assessments in these previous studies that we could detect in extracted samples in our study. Regarding the second difference, these previous studies on within-individual stability were conducted during the early parenting(14) or early romantic(15) periods, which engage the activity of the oxytocin system in particular ways(18). Instead, we used a normative sample that did not specify these inclusion criteria. Hence, we cannot exclude that during these specific periods the reliability of salivary and plasmatic oxytocin concentrations might be higher. We note though that our sample more closely resembles the samples used the vast majority of studies in the field (which sometimes even exclude participants during early parenthood(36)). Hence, our estimates of reliability are a better starter point for all studies where specific circumstances potentially affecting the activity of the oxytocin system have not been specified a priori.”

6) The paper misses a discussion of previous studies addressing links between salivary/ plasma levels and central oxytocin (e.g. in cerebrospinal fluid). I understand the claim that salivary oxytocin cannot be used to form an estimate of systemic absorption, although technically, a lack of a link between salivary and plasma levels, does not necessarily imply a lack of a relationship to e.g. central levels. The lack of effect is limited to this specific relationship.

In this study, we did not intend to investigate whether salivary and plasmatic oxytocin are valid proxies for the activity of the oxytocin system in the brain. Our data does not address that question and a thorough discussion of these studies falls, in our opinion, out of the scope of the manuscript. Instead, we focused on whether measurements of oxytocin in saliva and plasma (by far the most commonly used biological fluids to measure oxytocin) are sufficiently stable to provide valid indicators of the physiology of the oxytocin system in humans. Additionally, we also investigated whether salivary oxytocin can index plasmatic oxytocin at baseline and after the administration of synthetic oxytocin using different routes of administration.

A previous meta-analysis of studies correlating peripheral and CSF measurements of oxytocin has shown that most likely peripheral and CSF measurements do not correlate at baseline; significant correlations could be found after intranasal administration of oxytocin or specific experimental manipulations, such as stress(37). We believe that currently we still do not have a clear answer about the extent to which these peripheral fluids can actually index oxytocin concentrations in the brain (even if associations with CSF are evident in specific instances). For instance, no study has ever shown that CSF oxytocin actually predicts the concentrations of oxytocin in the extracellular fluid of the brain. Given what we currently know about the synaptic release of oxytocin in the brain(38) (in contrast with former theories of exclusive bulk diffusion in the CSF(39)), we think we have good reasons to suspect this might not be the case.

The only contribution our study can make in that respect is highlighting our current lack of understanding of how oxytocin reaches saliva if not from the blood. Currently there is no evidence of direct secretion of oxytocin to the saliva (not from acinar secretion or nerve terminals release). Hence, as it stands, the most likely mechanism for oxytocin to entry the saliva is from the blood (for instance, by ultrafiltration). If increases in plasmatic oxytocin after intravenous oxytocin cannot produce any significant increases in salivary oxytocin (shown in ours and in a previous study), how does oxytocin reach the saliva and why might it be able to predict concentrations in the CSF, if it does? In this respect, we hope our study highlights the need for further research shedding light on the mechanisms underlying these potential saliva – CSF relationships, if they exist. We would be glad to accommodate any other hypothesis the reviewer might have on this respect.

Line 522 “The lack of increase in salivary oxytocin after the intravenous administration of exogenous oxytocin that was consistently found in our study and in a previous study(3) also raises the question of how oxytocin reaches the saliva if not from the blood. Currently there is no evidence of direct acinar secretion or direct nerve terminals release of oxytocin to the saliva; therefore, transport from the blood remains as the most plausible mechanism of appearance of oxytocin in the saliva. Clarifying these mechanisms of transport is paramount, given the current hypothesis that salivary oxytocin might be superior to plasma in indexing central levels of oxytocin in the CSF(40).”

Methods

7) Related to the general comment, the variability in days between sessions is relatively high (average 8.80 days apart (SD 5.72; range 3-28). However, it appears that no explicit measures were taken to control the conducted analyses for this variability.

Thanks for point this out. Indeed, we were not sufficiently thorough in exploring the impact of this potential variability in the time gap between visits on our estimated ICCs. Thanks to the reviewer we now acknowledged this limitation of our analysis and decided to explore this further. We decided to run the following sensitivity analysis. First, we went back to our dataset A and identified all pairs of consecutive measures that were collected with an exact time interval of 7 days between visits. We could retrieve 15 examples of these pairs from 15 different participants for both saliva and plasma. Then, we recalculated the ICC and CV on this subset of our initial sample. In line with our main analysis, we found poor reliabilities for both salivary and plasmatic oxytocin; in both cases the ICCs were not significantly different from 0 and the CVs were 49% and 40%, respectively. This further analysis has been added to the revised version of the manuscript. We hope the reviewer shares our vision that our main conclusion of poor reliabilities of single measurements of baseline oxytocin in saliva and plasma cannot be simply attributed to the variability in the number of days between visits.

Line 229 “Since there was considerable variability in the time-interval between visits across participants, we conducted a sensitivity analysis where we repeated our reliability analysis focusing on 15 pairs of consecutive measures that were collected with an exact time interval of 7 days between visits in 15 participants. Here, we recalculated the ICC and CV on this subset of our initial sample, using the approach described above.”

Line 399 “These poor reliabilities are unlikely to be explained by variability in the time-interval between visits of the same individual, since we also found poor reliability indexes for both saliva and plasma when we restricted our analysis to a subset of our sample controlling for the exact number of days spacing visits.”*

8) A rationale for the adopted dosing and timing (115 min post administration) of the sample extraction is missing. Additionally, it seems that intravenous administrations were always given second, whereas intranasal administrations were given third, with a small delay of approximately 5 min. Hence, it seems that the timing of 115 min post-administration is only accurate for the intranasal administration.

We collected saliva samples before any treatment administration and after the end of our scanning session (collection of saliva samples in between was just not possible because the participants were inside the MRI machine and could not have moved their heads). For the plasma, we collected samples before any treatment administration, after each treatment administration and at other five time-points during the scanning session. Here, we only report the plasma data that was acquired concomitantly with the saliva samples (the full-time course of plasma changes in plasmatic oxytocin has been reported elsewhere(2)).

In the manuscript, we report post-administration times from the end of the full treatment administration protocol. Hence, as the reviewer highlights our post-administration sample was collected at around 115 mins from the last intranasal administration and 120 mins from the end of the intravenous administration. We have now made this aspect explicit in the revised version of the manuscript.

Line 162 “For the purposes of this report, we use the plasmatic and salivary oxytocin measurements that were obtained at baseline and at 115 minutes after the end of our last treatment administration (this means that our post-administration samples were collected 115 mins after the intranasal administrations and 120 mins after the intravenous administration of oxytocin).”

9) Since the ICC of baseline samples showed poor reliability, it seems suboptimal to pool across sessions for assessing the relationship between salivary and blood measurements. It should be possible to perform e.g. partial correlations on the actual scores, thereby correcting for the repeated measure (subject ID). Further, since the sample size is relatively small (13 subjects), it might be recommended to use non-parametric (e.g. Spearmann correlations) instead of Pearson. The additional reporting of the Bayes factor is appreciated; it is very informative.

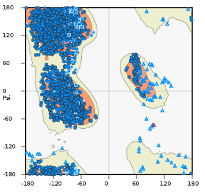

Thanks for the suggestion. In fact, for the correlation the reviewer mentions we indeed used a multilevel approach where we specified subject as a random effect (please see pages 9-10). This allowed us to deal with the dependence of measurements coming from the same subject in different visits. Furthermore, since we also had concerns about the sample size, we calculated Pearson correlations but used bootstrapping (1000 samples) to obtain the 95% confidence intervals and assess significance. Bootstrapping is a robust statistical technique which allows significance testing independently of any assumptions about the distribution of the data and is robust to outliers. Please see page 12 of the manuscript, section “Association between salivary and plasmatic oxytocin levels”.

10) Now, the authors only compared relationships between salivary and plasma levels, either at baseline or post administration. I'm wondering whether it would be interesting to explore relationships between pre-to-post change scores in salivary versus plasma measures.

Thanks for the suggestion. We have now conducted this further analysis and we could not find any significant correlation between changes from baseline to post-administration in any of our treatment conditions. As for our other correlation analyses, here we also conducted Bayesian inference, which supported the idea that the null hypothesis of no significant correlation between changes in saliva and plasma from baseline to post-administration is at least 4x more likely than the alternative hypothesis. This further analysis strengthens our confidence that changes in salivary oxytocin after administration of oxytocin using the intranasal and intravenous routes should not be used to predict systemic absorption to the plasma.

Line 260 “*As a final sanity check, we also investigated correlations between the changes from baseline to post-administration in saliva and plasma in each of our treatment conditions separately.”

Line 485 “Furthermore, we could not find any significant correlation between changes in salivary or plasmatic oxytocin from baseline to 115 mins after the end of our last treatment administration in any of our four treatment conditions. The lack of significant associations between salivary and plasmatic oxytocin (and respective changes from baseline) was further supported through our Bayesian analyses which demonstrated that given our data the null hypotheses were at least three times more likely than the alternative hypothesis.”*

11) Please provide more information on the outlier detection procedure (outlier labelling rule).

This information has now been added to the revised version of the manuscript.

Line 271 “Outliers were identified using the outlier labelling rule(41); this means that a data point was identified as an outlier if it was more than 1.5 x interquartile range above the third quartile or below the first quartile.”*

12) Please indicate how deviations from a Gaussian distribution were assessed.

We used the combined assessment of i) differences between mean and median; ii) skewness and kurtosis; iii) histogram; iv) Q-Q plots; and v) the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk normality tests. Deviations from a normal distribution is common in the concentration of several analytes in the saliva (42), including oxytocin (15); hence, following the current recommendations, we used log transformations of the raw concentrations but plot the raw concentrations to facilitate the interpretation of our plots.

Results

13) Please verify the degrees of freedom for the post-hoc tests performed to assess pre-post changes at each treatment level (e.g. baseline vs Post administration: Spray - t(122) = 7.06, p < 0.001) . Why is this 122? Shouldn't this be a simple paired-sample t-test with 13 subjects?

We apologize for this oversight. Indeed, we did a mistake in copying the values of the degrees of freedom from SPSS. We have now corrected these values. All the other p-values and F or T values were reported correctly and hence are not changed in the revised version of the manuscript (please see also response to Reviewer 1, question 4 regarding inconsistencies in the reported p-values).