Reviewer #1 (Public review):

I enjoyed reading this long but compelling account of the new (generalised) version of the Hierarchical Gaussian filter (HGF). Effectively, it describes an extension of the HGF to accommodate the influence of latent states on volatility - and vice versa. This paper describes a generalisation that has been made available to the community via the TAPAS software. This contribution will be of special interest to people in computational psychiatry, where the application of the HGF has been the most prevalent.

I thought the background, motivation, description and illustration of the scheme were excellent. The paper is rather long; however, it serves as a useful technical reference.

There are two issues that I think the authors need to address.

(1) The first is the failure to properly relate the current scheme to standard implementations of Bayesian filtering under hierarchical state-space models.

(2) The second is that whilst the paper is well-written, some of the mathematical notation is cluttered. Furthermore, I think that the authors need to motivate the otherwise overengineered description of the requisite variational message passing and decomposition into update steps.

I think that the authors can address both of these issues by including a technical section in the introduction, relating the HGF to state-of-the-art in the broader field of Bayesian filtering and predictive coding. They can then explain the benefits of the particular generative model - to which the HGF is committed - by drilling down on the update scheme and its implementation in the remainder of the paper.

I was underwhelmed by the account of predictive coding and its relationship to Bayesian filtering. I think that the authors should suppress the references to predictive coding in the recent machine learning literature. Rather, the presented narrative should emphasise the fact that predictive coding and Bayesian filtering are the same thing. The authors could then explain where the hierarchical Gaussian filter fits within Bayesian filtering and why its particular form lends itself to the variational updates they subsequently derive.

The authors could add something like the following to the introduction (accompanying PDF has the equations). There is a summary of what follows in the Wikipedia entry on generalised filtering, in particular, its relationship to predictive coding (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generalized_filtering).

Relationship to Existing Work

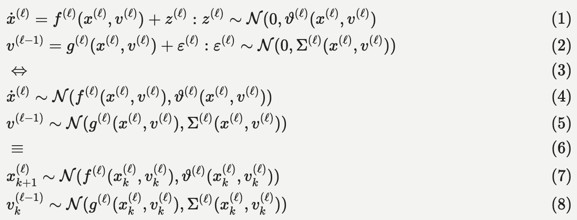

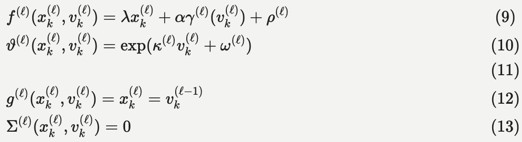

Technically, the hierarchical Gaussian filter is a Bayesian filter under a hierarchical state-space model. The most general form of these models can be expressed as stochastic differential or difference equations as follows, c.f., Equation 9 in (Feldman and Friston, 2010):

This functional form implies a hierarchical decomposition into hierarchical levels (l) that are linked through latent causes (v), with dynamics among latent states (x) at each level. From the perspective of the HGF, the state-dependency of state (z) and observation (e) noise at each level is a key feature. The variance (i.e., inverse precision) of the random fluctuations z is known as volatility, which - in a hierarchical setting - can depend upon latent causes and states at higher levels. The variational inversion of these models - sometimes called variational or generalised filtering - finds a number of important applications: a key example here is dynamic causal modelling, typically in the analysis of imaging timeseries. In this setting, unknown or latent states, parameters and precisions are updated in variational steps by minimising variational free energy (a variational bound on negative log marginal likelihood).

In engineering, the simplest form of generalised filtering is known as a Kalman filter, in which all the equations are linear, and volatility is assumed to be constant. In neurobiology, there is an intimate relationship between generalised filtering and predictive coding: predictive coding was originally introduced for timeseries analysis and compression of sound files (Elias, 1955). Subsequently, the implicit filtering or compression scheme was considered as a description of neuronal processing in the retina (Srinivasan et al., 1982) and then cortical hierarchies (Mumford, 1992; Rao, 1999; Rao and Ballard, 1999). The formal equivalence between predictive coding and Kalman filtering was noted in (Rao, 1999). Kalman filtering itself was then recognised as a special case of generalised filtering that could be read as predictive coding in the brain (Friston and Kiebel, 2009). The estimation of precision in these predictive coding schemes has been associated with endogenous (Feldman and Friston, 2010) and exogenous (Kanai et al., 2015) attention; i.e., with and without state dependency, respectively. Subsequently, precision estimation or uncertainty quantification has become a key focus in computational psychiatry.

In machine learning, there have been recent attempts to implement predictive coding via the minimisation of variational free energy under generative models with the functional form of conventional neural networks: e.g., (Millidge et al., 2022; Salvatori et al., 2022). However, much of this work is nascent and does not deal with dynamics or volatility. There is an interesting exception in machine learning, namely, transformer architectures, where the attention heads can be read as implementing a form of Kalman gain, namely, estimating state-dependent precision, e.g., (Buckley and Singh, 2024).

Within this general setting, the HGF emphasises the importance of precision estimation or uncertainty quantification by committing to a particular functional form for the generative model that can be summarised as follows:

"We will unpack this form below and show how it leads to a remarkably compact and efficient Bayesian belief updating scheme. We will appeal implicitly to variational message passing on factor graphs (Dauwels, 2007; Friston et al., 2017; Winn and Bishop, 2005) to decompose message passing between nodes and, crucially, within-node computations. These computations furnish a scalable and flexible form of generalised Bayesian filtering. In principle, this scheme inherits all the biological plausibility of belief propagation and variational message passing in cortical hierarchies (Friston et al., 2017)."

It might be worth the authors [re-]reading the abstracts of the above papers, for a clearer sense of how those in computational neuroscience and state-space modelling (but not machine learning) think about predictive coding and its relationship to Bayesian filtering. They could then go through the manuscript, nuancing your discussion of the intimate relationship between variational Bayes, generalised filtering, predictive coding and hierarchical Gaussian filtering.