Fluidity recognizes the highly flexible or permeableboundaries of OCs, where it is hard to figure out whois in the community and who is outside (Preece et al.2004) at any point in time, let alone over time. Theyare adaptive in that they change as the attention, actions,and interests of the collective of participants change overtime. Many individuals in an OC are at various stagesof exit and entry that change fluidly over time.

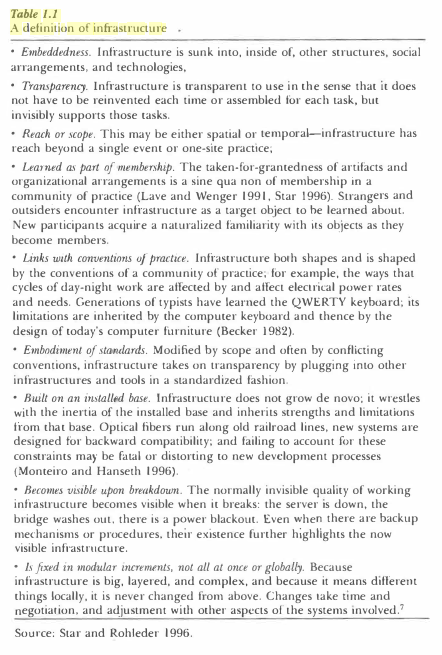

Evokes boundary objects and boundary infrastructures.