Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

We thank all the reviewers for their constructive comments. We have carefully considered your feedback and revised the manuscript accordingly. The major concern raised was the applicability of SegPore to the RNA004 dataset. To address this, we compared SegPore with f5c and Uncalled4 on RNA004, and found that SegPore demonstrated improved performance, as shown in Table 2 of the revised manuscript.

Following the reviewers’ recommendations, we updated Figures 3 and 4. Additionally, we added one table and three supplementary figures to the revised manuscript:

· Table 2: Segmentation benchmark on RNA004 data

· Supplementary Figure S4: RNA translocation hypothesis illustrated on RNA004 data

· Supplementary Figure S5: Illustration of Nanopolish raw signal segmentation with eventalign results

· Supplementary Figure S6: Running time of SegPore on datasets of varying sizes

Below, we provide a point-by-point response to your comments.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, the authors describe a new computational method (SegPore), which segments the raw signal from nanopore-direct RNA-Seq data to improve the identification of RNA modifications. In addition to signal segmentation, SegPore includes a Gaussian Mixture Model approach to differentiate modified and unmodified bases. SegPore uses Nanopolish to define a first segmentation, which is then refined into base and transition blocks. SegPore also includes a modification prediction model that is included in the output. The authors evaluate the segmentation in comparison to Nanopolish and Tombo, and they evaluate the impact on m6A RNA modification detection using data with known m6A sites. In comparison to existing methods, SegPore appears to improve the ability to detect m6A, suggesting that this approach could be used to improve the analysis of direct RNA-Seq data.

Strengths:

SegPore addresses an important problem (signal data segmentation). By refining the signal into transition and base blocks, noise appears to be reduced, leading to improved m6A identification at the site level as well as for single-read predictions. The authors provide a fully documented implementation, including a GPU version that reduces run time. The authors provide a detailed methods description, and the approach to refine segments appears to be new.

Weaknesses:

In addition to Nanopolish and Tombo, f5c and Uncalled4 can also be used for segmentation, however, the comparison to these methods is not shown.

The method was only applied to data from the RNA002 direct RNA-Sequencing version, which is not available anymore, currently, it remains unclear if the methods still work on RNA004.

Thank you for your comments.

To clarify the background, there are two kits for Nanopore direct RNA sequencing: RNA002 (the older version) and RNA004 (the newer version). Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) introduced the RNA004 kit in early 2024 and has since discontinued RNA002. Consequently, most public datasets are based on RNA002, with relatively few available for RNA004 (as of 30 June 2025).

Nanopolish and Tombo were developed for raw signal segmentation and alignment using RNA002 data, whereas f5c and Uncalled4are the only two software supporting RNA004 data. Since the development of SegPore began in January 2022, we initially focused on RNA002 due to its data availability. Accordingly, our original comparisons were made against Nanopolish and Tombo using RNA002 data.

We have now updated SegPore to support RNA004 and compared its performance against f5c and Uncalled4 on three public RNA004 datasets.

As shown in Table 2 of the revised manuscript, SegPore outperforms both f5c and Uncalled4 in raw signal segmentation. Moreover, the jiggling translocation hypothesis underlying SegPore is further supported, as shown in Supplementary Figure S4.

The overall improvement in accuracy appears to be relatively small.

Thank you for the comment.

We understand that the improvements shown in Tables 1 and 2 may appear modest at first glance due to the small differences in the reported standard deviation (std) values. However, even small absolute changes in std can correspond to substantial relative reductions in noise, especially when the total variance is low.

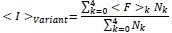

To better quantify the improvement, we assume that approximately 20% of the std for Nanopolish, Tombo, f5c, and Uncalled4 arises from noise. Using this assumption, we calculate the relative noise reduction rate of SegPore as follows:

Noise reduction rate = (baseline std − SegPore std) / (0.2 × baseline std)

Based on this formula, the average noise reduction rates across all datasets are:

- SegPore vs Nanopolish: 49.52%

- SegPore vs Tombo: 167.80%

- SegPore vs f5c: 9.44%

- SegPore vs Uncalled4: 136.70%

These results demonstrate that SegPore can reduce the noise level by at least 9% given a noise level of 20%, which we consider a meaningful improvement for downstream tasks, such as base modification detection and signal interpretation. The high noise reduction rates observed in Tombo and Uncalled4 (over 100%) suggest that their actual noise proportion may be higher than our 20% assumption.

We acknowledge that this 20% noise level assumption is an approximation. Our intention is to illustrate that SegPore provides measurable improvements in relative terms, even when absolute differences appear small.

The run time and resources that are required to run SegPore are not shown, however, it appears that the GPU version is essential, which could limit the application of this method in practice.

Thank you for your comment.

Detailed instructions for running SegPore are provided in github (https://github.com/guangzhaocs/SegPore). Regarding computational resources, SegPore currently requires one CPU core and one Nvidia GPU to perform the segmentation task efficiently.

We present SegPore’s runtime for typical datasets in Supplementary Figure S6 in the revised manuscript. For a typical 1 GB fast5 file, the segmentation takes approximately 9.4 hours using a single NVIDIA DGX‑1 V100 GPU and one CPU core.

Currently, GPU acceleration is essential to achieve practical runtimes with SegPore. We acknowledge that this requirement may limit accessibility in some environments. To address this, we are actively working on a full C++ implementation of SegPore that will support CPU-only execution. While development is ongoing, we aim to release this version in a future update.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The work seeks to improve the detection of RNA m6A modifications using Nanopore sequencing through improvements in raw data analysis. These improvements are said to be in the segmentation of the raw data, although the work appears to position the alignment of raw data to the reference sequence and some further processing as part of the segmentation, and result statistics are mostly shown on the 'data-assigned-to-kmer' level.

As such, the title, abstract, and introduction stating the improvement of just the 'segmentation' does not seem to match the work the manuscript actually presents, as the wording seems a bit too limited for the work involved.

The work itself shows minor improvements in m6Anet when replacing Nanopolish eventalign with this new approach, but clear improvements in the distributions of data assigned per kmer. However, these assignments were improved well enough to enable m6A calling from them directly, both at site-level and at read-level.

Strengths:

A large part of the improvements shown appear to stem from the addition of extra, non-base/kmer specific, states in the segmentation/assignment of the raw data, removing a significant portion of what can be considered technical noise for further analysis. Previous methods enforced the assignment of all raw data, forcing a technically optimal alignment that may lead to suboptimal results in downstream processing as data points could be assigned to neighbouring kmers instead, while random noise that is assigned to the correct kmer may also lead to errors in modification detection.

For an optimal alignment between the raw signal and the reference sequence, this approach may yield improvements for downstream processing using other tools.<br />

Additionally, the GMM used for calling the m6A modifications provides a useful, simple, and understandable logic to explain the reason a modification was called, as opposed to the black models that are nowadays often employed for these types of tasks.

Weaknesses:

The work seems limited in applicability largely due to the focus on the R9's 5mer models. The R9 flow cells are phased out and not available to buy anymore. Instead, the R10 flow cells with larger kmer models are the new standard, and the applicability of this tool on such data is not shown. We may expect similar behaviour from the raw sequencing data where the noise and transition states are still helpful, but the increased kmer size introduces a large amount of extra computing required to process data and without knowledge of how SegPore scales, it is difficult to tell how useful it will really be. The discussion suggests possible accuracy improvements moving to 7mers or 9mers, but no reason why this was not attempted.

Thank you for pointing out this important limitation. Please refer to our response to Point 1 of Reviewer 1 for SegPore’s performance on RNA004 data. Notably, the jiggling behavior is also observed in RNA004 data, and SegPore achieves better performance than both f5c and Uncalled4.

The increased k-mer size in RNA004 affects only the training phase of SegPore (refer to Supplementary Note 1, Figure 5 for details on the training and testing phases). Once the baseline means and standard deviations for each k-mer are established, applying SegPore to RNA004 data proceeds similarly to RNA002. This is because each k-mer in the reference sequence has, at most, two states (modified and unmodified). While the larger k-mer size increases the size of the parameter table, it does not increase the computational complexity during segmentation. Although estimating the initial k-mer parameter table requires significant time and effort on our part, it does not affect the runtime for end users applying SegPore to RNA004 data.

Extending SegPore from 5-mers to 7-mers or 9-mers for RNA002 data would require substantial effort to retrain the model and generate sufficient training data. Additionally, such an extension would make SegPore’s output incompatible with widely used upstream and downstream tools such as Nanopolish and m6Anet, complicating integration and comparison. For these reasons, we leave this extension for future work.

The manuscript suggests the eventalign results are improved compared to Nanopolish. While this is believably shown to be true (Table 1), the effect on the use case presented, downstream differentiation between modified and unmodified status on a base/kmer, is likely limited as during actual modification calling the noisy distributions are usually 'good enough', and not skewed significantly in one direction to really affect the results too terribly.

Thank you for your comment. While current state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods perform well on benchmark datasets, there remains significant room for improvement. Most SOTA evaluations are based on limited datasets, primarily covering DRACH motifs in human and mouse transcriptomes. However, m6A modifications can also occur in non-DRACH motifs, where current models may underperform. Additionally, other RNA modifications—such as pseudouridine, inosine, and m5C—are less studied, and their detection may benefit from improved signal modeling.

We would also like to emphasize that raw signal segmentation and RNA modification detection are distinct tasks. SegPore focuses on the former, providing a cleaner, more interpretable signal that can serve as a foundation for downstream tasks. Improved segmentation may facilitate the development of more accurate RNA modification detection algorithms by the community.

Scientific progress often builds incrementally through targeted improvements to foundational components. We believe that enhancing signal segmentation, as SegPore does, contributes meaningfully to the broader field—the full impact will become clearer as the tool is adopted into more complex workflows.

Furthermore, looking at alternative approaches where this kind of segmentation could be applied, Nanopolish uses the main segmentation+alignment for a first alignment and follows up with a form of targeted local realignment/HMM test for modification calling (and for training too), decreasing the need for the near-perfect segmentation+alignment this work attempts to provide. Any tool applying a similar strategy probably largely negates the problems this manuscript aims to improve upon.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment.

To clarify, Nanopolish provides three independent commands: polya, eventalign, and call-methylation.

- The polya command identifies the adapter, poly(A) tail, and transcript region in the raw signal.

- The eventalign command aligns the raw signal to a reference sequence, assigning a signal segment to individual k-mers in the reference.

- The call-methylation command detects methylated bases from DNA sequencing data.

The eventalign command corresponds to “the main segmentation+alignment for a first alignment,” while call-methylation corresponds to “a form of targeted local realignment/HMM test for modification calling,” as mentioned in the reviewer’s comment. SegPore’s segmentation is similar in purpose to Nanopolish’s eventalign, while its RNA modification estimation component is similar in concept to Nanopolish’s call-methylation.

We agree the general idea may appear similar, but the implementations are entirely different. Importantly, Nanopolish’s call-methylation is designed for DNA sequencing data, and its models are not trained to recognize RNA modifications. This means they address distinct research questions and cannot be directly compared on the same RNA modification estimation task. However, it is valid to compare them on the segmentation task, where SegPore exhibits better performance (Table 1).

We infer the reviewer may suggest that because m6Anet is a deep neural network capable of learning from noisy input, the benefit of more accurate segmentation (such as that provided by SegPore) might be limited. This concern may arise from the limited improvement of SegPore+m6Anet over Nanopolish+m6Anet in bulk analysis (Figure 3). Several factors may contribute to this observation:

(i) For reads aligned to the same gene in the in vivo data, alignment may be inaccurate due to pseudogenes or transcript isoforms.

(ii) The in vivo benchmark data are inherently more complex than in vitro datasets and may contain additional modifications (e.g., m5C, m7G), which can confound m6A calling by altering the signal baselines of k-mers.

(iii) m6Anet is trained on events produced by Nanopolish and may not be optimal for SegPore-derived events.

(iv) The benchmark dataset lacks a modification-free (IVT) control sample, making it difficult to establish a true baseline for each k-mer.

In the IVT data (Figure 4), SegPore shows a clear improvement in single-molecule m6A identification, with a 3~4% gain in both ROC-AUC and PR-AUC. This demonstrates SegPore’s practical benefit for applications requiring higher sensitivity at the molecule level.

As noted earlier, SegPore’s contribution lies in denoising and improving the accuracy of raw signal segmentation, which is a foundational step in many downstream analyses. While it may not yet lead to a dramatic improvement in all applications, it already provides valuable insights into the sequencing process (e.g., cleaner signal profiles in Figure 4) and enables measurable gains in modification detection at the single-read level. We believe SegPore lays the groundwork for developing more accurate and generalizable RNA modification detection tools beyond m6A.

We have also added the following sentence in the discussion to highlight SegPore’s limited performance in bulk analysis:

“The limited improvement of SegPore combined with m6Anet over Nanopolish+m6Anet in bulk in vivo analysis (Figure 3) may be explained by several factors: potential alignment inaccuracies due to pseudogenes or transcript isoforms, the complexity of in vivo datasets containing additional RNA modifications (e.g., m5C, m7G) affecting signal baselines, and the fact that m6Anet is specifically trained on events produced by Nanopolish rather than SegPore. Additionally, the lack of a modification-free control (in vitro transcribed) sample in the benchmark dataset makes it difficult to establish true baselines for each k-mer. Despite these limitations, SegPore demonstrates clear improvement in single-molecule m6A identification in IVT data (Figure 4), suggesting it is particularly well suited for in vitro transcription data analysis.”

Finally, in the segmentation/alignment comparison to Nanopolish, the latter was not fitted(/trained) on the same data but appears to use the pre-trained model it comes with. For the sake of comparing segmentation/alignment quality directly, fitting Nanopolish on the same data used for SegPore could remove the influences of using different training datasets and focus on differences stemming from the algorithm itself.

In the segmentation benchmark (Table 1), SegPore uses the fixed 5-mer parameter table provided by ONT. The hyperparameters of the HHMM are also fixed and not estimated from the raw signal data being segmented. Only in the m6A modification task, SegPore does perform re-estimation of the baselines for the modified and unmodified states of k-mers. Therefore, the comparison with Nanopolish is fair, as both tools rely on pre-defined models during segmentation.

Appraisal:

The authors have shown their method's ability to identify noise in the raw signal and remove their values from the segmentation and alignment, reducing its influences for further analyses. Figures directly comparing the values per kmer do show a visibly improved assignment of raw data per kmer. As a replacement for Nanopolish eventalign it seems to have a rather limited, but improved effect, on m6Anet results. At the single read level modification modification calling this work does appear to improve upon CHEUI.

Impact:

With the current developments for Nanopore-based modification largely focusing on Artificial Intelligence, Neural Networks, and the like, improvements made in interpretable approaches provide an important alternative that enables a deeper understanding of the data rather than providing a tool that plainly answers the question of whether a base is modified or not, without further explanation. The work presented is best viewed in the context of a workflow where one aims to get an optimal alignment between raw signal data and the reference base sequence for further processing. For example, as presented, as a possible replacement for Nanopolish eventalign. Here it might enable data exploration and downstream modification calling without the need for local realignments or other approaches that re-consider the distribution of raw data around the target motif, such as a 'local' Hidden Markov Model or Neural Networks. These possibilities are useful for a deeper understanding of the data and further tool development for modification detection works beyond m6A calling.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

Nucleotide modifications are important regulators of biological function, however, until recently, their study has been limited by the availability of appropriate analytical methods. Oxford Nanopore direct RNA sequencing preserves nucleotide modifications, permitting their study, however, many different nucleotide modifications lack an available base-caller to accurately identify them. Furthermore, existing tools are computationally intensive, and their results can be difficult to interpret.

Cheng et al. present SegPore, a method designed to improve the segmentation of direct RNA sequencing data and boost the accuracy of modified base detection.

Strengths:

This method is well-described and has been benchmarked against a range of publicly available base callers that have been designed to detect modified nucleotides.

Weaknesses:

However, the manuscript has a significant drawback in its current version. The most recent nanopore RNA base callers can distinguish between different ribonucleotide modifications, however, SegPore has not been benchmarked against these models.

I recommend that re-submission of the manuscript that includes benchmarking against the rna004_130bps_hac@v5.1.0 and rna004_130bps_sup@v5.1.0 dorado models, which are reported to detect m5C, m6A_DRACH, inosine_m6A and PseU.<br />

A clear demonstration that SegPore also outperforms the newer RNA base caller models will confirm the utility of this method.

Thank you for highlighting this important limitation. While Dorado, the new ONT basecaller, is publicly available and supports modification-aware basecalling, suitable public datasets for benchmarking m5C, inosine, m6A, and PseU detection on RNA004 are currently lacking. Dorado’s modification-aware models are trained on ONT’s internal data, which is not publicly released. Therefore, it is not currently feasible to evaluate or directly compare SegPore’s performance against Dorado for m5C, inosine, m6A, and PseU detection.

We would also like to emphasize that SegPore’s main contribution lies in raw signal segmentation, which is an upstream task in the RNA modification detection pipeline. To assess its performance in this context, we benchmarked SegPore against f5c and Uncalled4 on public RNA004 datasets for segmentation quality. Please refer to our response to Point 1 of Reviewer 1 for details.

Our results show that the characteristic “jiggling” behavior is also observed in RNA004 data (Supplementary Figure S4), and SegPore achieves better segmentation performance than both f5c and Uncalled4 (Table 2).

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewing Editor:

Please note that we also received the following comments on the submission, which we encourage you to take into account:

took a look at the work and for what I saw it only mentions/uses RNA002 chemistry, which is deprecated, effectively making this software unusable by anyone any more, as RNA002 is not commercially available. While the results seem promising, the authors need to show that it would work for RNA004. Notably, there is an alternative software for resquiggling for RNA004 (not Tombo or Nanopolish, but the GPU-accelerated version of Nanopolish (f5C), which does support RNA004. Therefore, they need to show that SegPore works for RNA004, because otherwise it is pointless to see that this method works better than others if it does not support current sequencing chemistries and only works for deprecated chemistries, and people will keep using f5C because its the only one that currently works for RNA004. Alternatively, if there would be biological insights won from the method, one could justify not implementing it in RNA004, but in this case, RNA002 is deprecated since March 2024, and the paper is purely methodological.

Thank you for the comment. We agree that support for current sequencing chemistries is essential for practical utility. While SegPore was initially developed and benchmarked on RNA002 due to the availability of public data, we have now extended SegPore to support RNA004 chemistry.

To address this concern, we performed a benchmark comparison using public RNA004 datasets against tools specifically designed for RNA004, including f5c and Uncalled4. Please refer to our response to Point 1 of Reviewer 1 for details. The results show that SegPore consistently outperforms f5c and Uncalled4 in segmentation accuracy on RNA004 data.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

Various statements are made throughout the text that require further explanation, which might actually be defined in more detail elsewhere sometimes but are simply hard to find in the current form.

(1) Page 2, “In this technique, five nucleotides (5mers) reside in the nanopore at a time, and each 5mer generates a characteristic current signal based on its unique sequence and chemical properties (16).”

5mer? Still on R9 or just ignoring longer range influences, relevant? It is indeed a R9.4 model from ONT.

Thank you for the observation. We apologize for the confusion and have clarified the relevant paragraph to indicate that the method is developed for RNA002 data by default. Specifically, we have added the following sentence:

“Two versions of the direct RNA sequencing (DRS) kits are available: RNA002 and RNA004. Unless otherwise specified, this study focuses on RNA002 data.”

(2) Page 3, “Employ models like Hidden Markov Models (HMM) to segment the signal, but they are prone to noise and inaccuracies.”

That's the alignment/calling part, not the segmentation?

Thank you for the comment. We apologize for the confusion. To clarify the distinction between segmentation and alignment, we added a new paragraph before the one in question to explain the general workflow of Nanopore DRS data analysis and to clearly define the task of segmentation. The added text reads:

“The general workflow of Nanopore direct RNA sequencing (DRS) data analysis is as follows. First, the raw electrical signal from a read is basecalled using tools such as Guppy or Dorado, which produce the nucleotide sequence of the RNA molecule. However, these basecalled sequences do not include the precise start and end positions of each ribonucleotide (or k-mer) in the signal. Because basecalling errors are common, the sequences are typically mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome using minimap2 to recover the correct reference sequence. Next, tools such as Nanopolish and Tombo align the raw signal to the reference sequence to determine which portion of the signal corresponds to each k-mer. We define this process as the segmentation task, referred to as "eventalign" in Nanopolish. Based on this alignment, Nanopolish extracts various features—such as the start and end positions, mean, and standard deviation of the signal segment corresponding to a k-mer. This signal segment or its derived features is referred to as an "event" in Nanopolish.”

We also revised the following paragraph describing SegPore to more clearly contrast its approach:

“In SegPore, we first segment the raw signal into small fragments using a Hierarchical Hidden Markov Model (HHMM), where each fragment corresponds to a sub-state of a k-mer. Unlike Nanopolish and Tombo, which directly align the raw signal to the reference sequence, SegPore aligns the mean values of these small fragments to the reference. After alignment, we concatenate all fragments that map to the same k-mer into a larger segment, analogous to the "eventalign" output in Nanopolish. For RNA modification estimation, we use only the mean signal value of each reconstructed event.”

We hope this revision clarifies the difference between segmentation and alignment in the context of our method and resolves the reviewer’s concern.

(3) Page 4, Figure 1, “These segments are then aligned with the 5mer list of the reference sequence fragment using a full/partial alignment algorithm, based on a 5mer parameter table. For example, 𝐴𝑗 denotes the base "A" at the j-th position on the reference.”

I think I do understand the meaning, but I do not understand the relevance of the Aj bit in the last sentence. What is it used for?

When aligning the segments (output from Step 2) to the reference sequence in Step 3, it is possible for multiple segments to align to the same k-mer. This can occur particularly when the reference contains consecutive identical bases, such as multiple adenines (A). For example, as shown in Fig. 1A, Step 3, the first two segments (μ₁ and μ₂) are aligned to the first 'A' in the reference sequence, while the third segment is aligned to the second 'A'. In this case, the reference sequence AACTGGTTTC...GTC, which contains exactly two consecutive 'A's at the start. This notation helps to disambiguate segment alignment in regions with repeated bases.

Additionally, this figure and its subscript include mapping with Guppy and Minimap2 but do not mention Nanopolish at all, while that seems an equally important step in the preprocessing (pg5). As such it is difficult to understand the role Nanopolish exactly plays. It's also not mentioned explicitly in the SegPore Workflow on pg15, perhaps it's part of step 1 there?

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. We apologize for the confusion. As mentioned in the public response to point 3 of Reviewer 2, SegPore uses Nanopolish to identify the poly(A) tail and transcript regions from the raw signal. SegPore then performs segmentation and alignment on the transcript portion only. This step is indeed part of Step 1 in the preprocessing workflow, as described in Supplementary Note 1, Section 3.

To clarify this in the main text, we have updated the preprocessing paragraph on page 6 to explicitly describe the role of Nanopolish:

“We begin by performing basecalling on the input fast5 file using Guppy, which converts the raw signal data into ribonucleotide sequences. Next, we align the basecalled sequences to the reference genome using Minimap2, generating a mapping between the reads and the reference sequences. Nanopolish provides two independent commands: "polya" and "eventalign".

The "polya" command identifies the adapter, poly(A) tail, and transcript region in the raw signal, which we refer to as the poly(A) detection results. The raw signal segment corresponding to the poly(A) tail is used to standardize the raw signal for each read. The "eventalign" command aligns the raw signal to a reference sequence, assigning a signal segment to individual k-mers in the reference. It also computes summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) from the signal segment for each k-mer. Each k-mer together with its corresponding signal features is termed an event. These event features are then passed into downstream tools such as m6Anet and CHEUI for RNA modification detection. For full transcriptome analysis (Figure 3), we extract the aligned raw signal segment and reference sequence segment from Nanopolish's events for each read by using the first and last events as start and end points. For in vitro transcription (IVT) data with a known reference sequence (Figure 4), we extract the raw signal segment corresponding to the transcript region for each input read based on Nanopolish’s poly(A) detection results.”

Additionally, we revised the legend of Figure 1A to explicitly include Nanopolish in step 1 as follows:

“The raw current signal fragments are paired with the corresponding reference RNA sequence fragments using Nanopolish.”

(4) Page 5, “The output of Step 3 is the "eventalign," which is analogous to the output generated by the Nanopolish "eventalign" command.”

Naming the function of Nanopolish, the output file, and later on (pg9) the alignment of the newly introduced methods the exact same "eventalign" is very confusing.

Thank you for the helpful comment. We acknowledge the potential confusion caused by using the term “eventalign” in multiple contexts. To improve clarity, we now consistently use the term “events” to refer to the output of both Nanopolish and SegPore, rather than using "eventalign" as a noun. We also added the following sentence to Step 3 (page 6) to clearly define what an “event” refers to in our manuscript:

“An "event" refers to a segment of the raw signal that is aligned to a specific k-mer on a read, along with its associated features such as start and end positions, mean current, standard deviation, and other relevant statistics.”

We have revised the text throughout the manuscript accordingly to reduce ambiguity and ensure consistent terminology.

(5) Page 5, “Once aligned, we use Nanopolish's eventalign to obtain paired raw current signal segments and the corresponding fragments of the reference sequence, providing a precise association between the raw signals and the nucleotide sequence.”

I thought the new method's HHMM was supposed to output an 'eventalign' formatted file. As this is not clearly mentioned elsewhere, is this a mistake in writing? Is this workflow dependent on Nanopolish 'eventalign' function and output or not?

We apologize for the confusion. To clarify, SegPore is not dependent on Nanopolish’s eventalign function for generating the final segmentation results. As described in our response to your comment point 2 and elaborated in the revised text on page 4, SegPore uses its own HHMM-based segmentation model to divide the raw signal into small fragments, each corresponding to a sub-state of a k-mer. These fragments are then aligned to the reference sequence based on their mean current values.

As explained in the revised manuscript:

“In SegPore, we first segment the raw signal into small fragments using a Hierarchical Hidden Markov Model (HHMM), where each fragment corresponds to a sub-state of a k-mer. Unlike Nanopolish and Tombo, which directly align the raw signal to the reference sequence, SegPore aligns the mean values of these small fragments to the reference. After alignment, we concatenate all fragments that map to the same k-mer into a larger segment, analogous to the "eventalign" output in Nanopolish. For RNA modification estimation, we use only the mean signal value of each reconstructed event.”

To avoid ambiguity, we have also revised the sentence on page 5 to more clearly distinguish the roles of Nanopolish and SegPore in the workflow. The updated sentence now reads:

“Nanopolish provides two independent commands: "polya" and "eventalign".

The "polya" command identifies the adapter, poly(A) tail, and transcript region in the raw signal, which we refer to as the poly(A) detection results. The raw signal segment corresponding to the poly(A) tail is used to standardize the raw signal for each read. The "eventalign" command aligns the raw signal to a reference sequence, assigning a signal segment to individual k-mers in the reference. It also computes summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) from the signal segment for each k-mer. Each k-mer together with its corresponding signal features is termed an event. These event features are then passed into downstream tools such as m6Anet and CHEUI for RNA modification detection. For full transcriptome analysis (Figure 3), we extract the aligned raw signal segment and reference sequence segment from Nanopolish's events for each read by using the first and last events as start and end points. For in vitro transcription (IVT) data with a known reference sequence (Figure 4), we extract the raw signal segment corresponding to the transcript region for each input read based on Nanopolish’s poly(A) detection results.”

(6) Page 5, “Since the polyA tail provides a stable reference, we normalize the raw current signals across reads, ensuring that the mean and standard deviation of the polyA tail are consistent across all reads.”

Perhaps I misread this statement: I interpret it as using the PolyA tail to do the normalization, rather than using the rest of the signal to do the normalization, and that results in consistent PolyA tails across all reads.

If it's the latter, this should be clarified, and a little detail on how the normalization is done should be added, but if my first interpretation is correct:

I'm not sure if its standard deviation is consistent across reads. The (true) value spread in this section of a read should be fairly limited compared to the rest of the signal in the read, so the noise would influence the scale quite quickly, and such noise might be introduced to pores wearing down and other technical influences. Is this really better than using the non-PolyA tail part of the reads signal, using Median Absolute Deviation to scale for a first alignment round, then re-fitting the signal scaling using Theil Sen on the resulting alignments (assigned read signal vs reference expected signal), as Tombo/Nanopolish (can) do?

Additionally, this kind of normalization should have been part of the Nanopolish eventalign already, can this not be re-used? If it's done differently it may result in different distributions than the ONT kmer table obtained for the next step.

Thank you for this detailed and thoughtful comment. We apologize for the confusion. The poly(A) tail–based normalization is indeed explained in Supplementary Note 1, Section 3, but we agree that the motivation needed to be clarified in the main text.

We have now added the following sentence in the revised manuscript (before the original statement on page 5 to provide clearer context:

“Due to inherent variability between nanopores in the sequencing device, the baseline levels and standard deviations of k-mer signals can differ across reads, even for the same transcript. To standardize the signal for downstream analyses, we extract the raw current signal segments corresponding to the poly(A) tail of each read. Since the poly(A) tail provides a stable reference, we normalize the raw current signals across reads, ensuring that the mean and standard deviation of the poly(A) tail are consistent across all reads. This step is crucial for reducing…..”

We chose to use the poly(A) tail for normalization because it is sequence-invariant—i.e., all poly(A) tails consist of identical k-mers, unlike transcript sequences which vary in composition. In contrast, using the transcript region for normalization can introduce biases: for instance, reads with more diverse k-mers (having inherently broader signal distributions) would be forced to match the variance of reads with more uniform k-mers, potentially distorting the baseline across k-mers.

In our newly added RNA004 benchmark experiment, we used the default normalization provided by f5c, which does not include poly(A) tail normalization. Despite this, SegPore was still able to mask out noise and outperform both f5c and Uncalled4, demonstrating that our segmentation method is robust to different normalization strategies.

(7) Page 7, “The initialization of the 5mer parameter table is a critical step in SegPore's workflow. By leveraging ONT's established kmer models, we ensure that the initial estimates for unmodified 5mers are grounded in empirical data.”

It looks like the method uses Nanopolish for a first alignment, then improves the segmentation matching the reference sequence/expected 5mer values. I thought the Nanopolish model/tables are based on the same data, or similarly obtained. If they are different, then why the switch of kmer model? Now the original alignment may have been based on other values, and thus the alignment may seem off with the expected kmer values of this table.

Thank you for this insightful question. To clarify, SegPore uses Nanopolish only to identify the poly(A) tail and transcript regions from the raw signal. In the bulk in vivo data analysis, we use Nanopolish’s first event as the start and the last event as the end to extract the aligned raw signal chunk and its corresponding reference sequence. Since SegPore relies on Nanopolish solely to delineate the transcript region for each read, it independently aligns the raw signals to the reference sequence without refining or adjusting Nanopolish’s segmentation results.

While SegPore's 5-mer parameter table is initially seeded using ONT’s published unmodified k-mer models, we acknowledge that empirical signal values may deviate from these reference models due to run-specific technical variation and the presence of RNA modifications. For this reason, SegPore includes a parameter re-estimation step to refine the mean and standard deviation values of each k-mer based on the current dataset.

The re-estimation process consists of two layers. In the outer layer, we select a set of 5mers that exhibit both modified and unmodified states based on the GMM results (Section 6 of Supplementary Note 1), while the remaining 5mers are assumed to have only unmodified states. In the inner layer, we align the raw signals to the reference sequences using the 5mer parameter table estimated in the outer layer (Section 5 of Supplementary Note 1). Based on the alignment results, we update the 5mer parameter table in the outer layer. This two-layer process is generally repeated for 3~5 iterations until the 5mer parameter table converges.This re-estimation ensures that:

(1) The adjusted 5mer signal baselines remain close to the ONT reference (for consistency);

(2) The alignment score between the observed signal and the reference sequence is optimized (as detailed in Equation 11, Section 5 of Supplementary Note 1);

(3) Only 5mers that show a clear difference between the modified and unmodified components in the GMM are considered subject to modification.

By doing so, SegPore achieves more accurate signal alignment independent of Nanopolish’s models, and the alignment is directly tuned to the data under analysis.

(8) Page 9, “The output of the alignment algorithm is an eventalign, which pairs the base blocks with the 5mers from the reference sequence for each read (Fig. 1C).”

“Modification prediction

After obtaining the eventalign results, we estimate the modification state of each motif using the 5mer parameter table.”

This wording seems to have been introduced on page 5 but (also there) reads a bit confusingly as the name of the output format, file, and function are now named the exact same "eventalign". I assume the obtained eventalign results now refer to the output of your HHMM, and not the original Nanopolish eventalign results, based on context only, but I'd rather have a clear naming that enables more differentiation.

We apologize for the confusion. We have revised the sentence as follows for clarity:

“A detailed description of both alignment algorithms is provided in Supplementary Note 1. The output of the alignment algorithm is an alignment that pairs the base blocks with the 5mers from the reference sequence for each read (Fig. 1C). Base blocks aligned to the same 5-mer are concatenated into a single raw signal segment (referred to as an “event”), from which various features—such as start and end positions, mean current, and standard deviation—are extracted. Detailed derivation of the mean and standard deviation is provided in Section 5.3 in Supplementary Note 1. In the remainder of this paper, we refer to these resulting events as the output of eventalign analysis or the segmentation task. ”

(9) Page 9, “Since a single 5mer can be aligned with multiple base blocks, we merge all aligned base blocks by calculating a weighted mean. This weighted mean represents the single base block mean aligned with the given 5mer, allowing us to estimate the modification state for each site of a read.”

I assume the weights depend on the length of the segment but I don't think it is explicitly stated while it should be.

Thank you for the helpful observation. To improve clarity, we have moved this explanation to the last paragraph of the previous section (see response to point 8), where we describe the segmentation process in more detail.

Additionally, a complete explanation of how the weighted mean is computed is provided in Section 5.3 of Supplementary Note 1. It is derived from signal points that are assigned to a given 5mer.

(10) Page 10, “Afterward, we manually adjust the 5mer parameter table using heuristics to ensure that the modified 5mer distribution is significantly distinct from the unmodified distribution.”

Using what heuristics? If this is explained in the supplementary notes then please refer to the exact section.

Thank you for pointing this out. The heuristics used to manually adjust the 5mer parameter table are indeed explained in detail in Section 7 of Supplementary Note 1.

To clarify this in the manuscript, we have revised the sentence as follows:

“Afterward, we manually adjust the 5mer parameter table using heuristics to ensure that the modified 5mer distribution is significantly distinct from the unmodified distribution (see details in Section 7 of Supplementary Note 1).”

(11) Page 10, “Once the table is fixed, it is used for RNA modification estimation in the test data without further updates.”

By what tool/algorithm? Perhaps it is your own implementation, but with the next section going into segmentation benchmarking and using Nanopolish before this seems undefined.

Thank you for pointing this out. We use our own implementation. See Algorithm 3 in Section 6 of Supplementary Note 1.

We have revised the sentence for clarity:

“Once a stabilized 5mer parameter table is estimated from the training data, it is used for RNA modification estimation in the test data without further updates. A more detailed description of the GMM re-estimation process is provided in Section 6 of Supplementary Note 1.”

(12) Page 11, “A 5mer was considered significantly modified if its read coverage exceeded 1,500 and the distance between the means of the two Gaussian components in the GMM was greater than 5.”

Considering the scaling done before also not being very detailed in what range to expect, this cutoff doesn't provide any useful information. Is this a pA value?

Thank you for the observation. Yes, the value refers to the current difference measured in picoamperes (pA). To clarify this, we have revised the sentence in the manuscript to include the unit explicitly:

“A 5mer was considered significantly modified if its read coverage exceeded 1,500 and the distance between the means of the two Gaussian components in the GMM was greater than 5 picoamperes (pA).”

(13) Page 13, “The raw current signals, as shown in Figure 1B.”

Wrong figure? Figure 2B seems logical.

Thank you for catching this. You are correct—the reference should be to Figure 2B, not Figure 1B. We have corrected this in the revised manuscript.

(14) Page 14, Figure 2A, these figures supposedly support the jiggle hypothesis but the examples seem to match only half the explanation. Any of these jiggles seem to be followed shortly by another in the opposite direction, and the amplitude seems to match better within each such pair than the next or previous segments. Perhaps there is a better explanation still, and this behaviour can be modelled as such instead.

Thank you for your comment. We acknowledge that the observed signal patterns may appear ambiguous and could potentially suggest alternative explanations. However, as shown in Figure 2A, the red dots tend to align closely with the baseline of the previous state, while the blue dots align more closely with the baseline of the next state. We interpret this as evidence for the "jiggling" hypothesis, where k-mer temporarily oscillates between adjacent states during translocation.

That said, we agree that more sophisticated models could be explored to better capture this behavior, and we welcome suggestions or references to alternative models. We will consider this direction in future work.

(15) Page 15, “This occurs because subtle transitions within a base block may be mistaken for transitions between blocks, leading to inflated transition counts.”

Is it really a "subtle transition" if it happens within a base block? It seems this is not a transition and thus shouldn't be named as such.

Thank you for pointing this out. We agree that the term “subtle transition” may be misleading in this context. We revised the sentence to clarify the potential underlying cause of the inflated transition counts:

“This may be due to a base block actually corresponding to a sub-state of a single 5mer, rather than each base block corresponding to a full 5mer, leading to inflated transition counts. To address this issue, SegPore’s alignment algorithm was refined to merge multiple base blocks (which may represent sub-states of the same 5mer) into a single 5mer, thereby facilitating further analysis.”

(16) Page 15, “The SegPore "eventalign" output is similar to Nanopolish's "eventalign" command.”

To the output of that command, I presume, not to the command itself.

Thank you for pointing out the ambiguity. We have revised the sentence for clarity:

“The final outputs of SegPore are the events and modification state predictions. SegPore’s events are similar to the outputs of Nanopolish’s "eventalign" command, in that they pair raw current signal segments with the corresponding RNA reference 5-mers. Each 5-mer is associated with various features — such as start and end positions, mean current, and standard deviation — derived from the paired signal segment.”

(17) Page 15, “For selected 5mers, SegPore also provides the modification rate for each site and the modification state of that site on individual reads.”

What selection? Just all kmers with a possible modified base or a more specific subset?

We revised the sentence to clarify the selection criteria:

“For selected 5mers that exhibit both a clearly unmodified and a clearly modified signal component, SegPore reports the modification rate at each site, as well as the modification state of that site on individual reads.”

(18) Page 16, “A key component of SegPore is the 5mer parameter table, which specifies the mean and standard deviation for each 5mer in both modified and unmodified states (Figure 2A).”

Wrong figure?

Thank you for pointing this out. You are correct—it should be Figure 1A, not Figure 2A. We intended to visually illustrate the structure of the 5mer parameter table in Figure 1A, and we have corrected this reference in the revised manuscript.

(19) Page 16, Table 1, I can't quite tell but I assume this is based on all kmers in the table, not just a m6A modified subset. A short added statement to make this clearer would help.

Yes, you are right—it is averaged over all 5mers. We have revised the sentence for clarity as follows:

" As shown in Table 1, SegPore consistently achieved the best performance averaged on all 5mers across all datasets..…."

(20) Page 16, “Since the peaks (representing modified and unmodified states) are separable for only a subset of 5mers, SegPore can provide modification parameters for these specific 5mers. For other 5mers, modification state predictions are unavailable.”

Can this be improved using some heuristics rather than the 'distance of 5' cutoff as described before? How small or big is this subset, compared to how many there should be to cover all cases?

We agree that more sophisticated strategies could potentially improve performance. In this study, we adopted a relatively conservative approach to minimize false positives by using a heuristic cutoff of 5 picoamperes. This value was selected empirically and we did not explore alternative cutoffs. Future work could investigate more refined or data-driven thresholding strategies.

(21) Page 16, “Tombo used the "resquiggle" method to segment the raw signals, and we standardized the segments using the polyA tail to ensure a fair comparison.”

I don't know what or how something is "standardized" here.

Standardized’ refers to the poly(A) tail–based signal normalization described in our response to point 6. We applied this normalization to Tombo’s output to ensure a fair comparison across methods. Without this standardization, Tombo’s performance was notably worse. We revised the sentence as follows:

“Tombo used the "resquiggle" method to segment the raw signals, and we standardized the segments using the poly(A) tail to ensure a fair comparison (See preprocessing section in Materials and Methods).”

(22) Page 16, “To benchmark segmentation performance, we used two key metrics: (1) the log-likelihood of the segment mean, which measures how closely the segment matches ONT's 5mer parameter table (used as ground truth), and (2) the standard deviation (std) of the segment, where a lower std indicates reduced noise and better segmentation quality. If the raw signal segment aligns correctly with the corresponding 5mer, its mean should closely match ONT's reference, yielding a high log-likelihood. A lower std of the segment reflects less noise and better performance overall.”

Here the segmentation part becomes a bit odd:

A: Low std can be/is achieved by dropping any noisy bits, making segments really small (partly what happens here with the transition segments). This may be 'true' here, in the sense that the transition is not really part of the segment, but the comparison table is a bit meaningless as the other tools forcibly assign all data to kmers, instead of ignoring parts as transition states. In other words, it is a benchmark that is easy to cheat by assigning more data to noise/transition states.

B: The values shown are influenced by the alignment made between the read and expected reference signal. Especially Tombo tends to forcibly assign data to whatever looks the most similar nearby rather than providing the correct alignment. So the "benchmark of the segmentation performance" is more of an "overall benchmark of the raw signal alignment". Which is still a good, useful thing, but the text seems to suggest something else.

Thank you for raising these important concerns regarding the segmentation benchmarking.

Regarding point A, the base blocks aligned to the same 5mer are concatenated into a single segment, including the short transition blocks between them. These transition blocks are typically very short (4~10 signal points, average 6 points), while a typical 5mer segment contains around 20~60 signal points. To assess whether SegPore’s performance is inflated by excluding transition segments, we conducted an additional comparison: we removed 6 boundary signal points (3 from the start and 3 from the end) from each 5mer segment in Nanopolish and Tombo’s results to reduce potential noise. The new comparison table is shown in the following:

SegPore consistently demonstrates superior performance. Its key contribution lies in its ability to recognize structured noise in the raw signal and to derive more accurate mean and standard deviation values that more faithfully represent the true state of the k-mer in the pore. The improved mean estimates are evidenced by the clearly separated peaks of modified and unmodified 5mers in Figures 3A and 4B, while the improved standard deviation is reflected in the segmentation benchmark experiments.

Regarding point B, we apologize for the confusion. We have added a new paragraph to the introduction to clarify that the segmentation task indeed includes the alignment step.

“The general workflow of Nanopore direct RNA sequencing (DRS) data analysis is as follows. First, the raw electrical signal from a read is basecalled using tools such as Guppy or Dorado, which produce the nucleotide sequence of the RNA molecule. However, these basecalled sequences do not include the precise start and end positions of each ribonucleotide (or k-mer) in the signal. Because basecalling errors are common, the sequences are typically mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome using minimap2 to recover the correct reference sequence. Next, tools such as Nanopolish and Tombo align the raw signal to the reference sequence to determine which portion of the signal corresponds to each k-mer. We define this process as the segmentation task, referred to as "eventalign" in Nanopolish. Based on this alignment, Nanopolish extracts various features—such as the start and end positions, mean, and standard deviation of the signal segment corresponding to a k-mer. This signal segment or its derived features is referred to as an "event" in Nanopolish. The resulting events serve as input for downstream RNA modification detection tools such as m6Anet and CHEUI.”

(23) Page 17 “Given the comparable methods and input data requirements, we benchmarked SegPore against several baseline tools, including Tombo, MINES (26), Nanom6A (27), m6Anet, Epinano (28), and CHEUI (29).”

It seems m6Anet is actually Nanopolish+m6Anet in Figure 3C, this needs a minor clarification here.

m6Anet uses Nanopolish’s estimated events as input by default.

(24) Page 18, Figure 3, A and B are figures without any indication of what is on the axis and from the text I believe the position next to each other on the x-axis rather than overlapping is meaningless, while their spread is relevant, as we're looking at the distribution of raw values for this 5mer. The figure as is is rather confusing.

Thanks for pointing out the confusion. We have added concrete values to the axes in Figures 3A and 3B and revised the figure legend as follows in the manuscript:

“(A) Histogram of the estimated mean from current signals mapped to an example m6A-modified genomic location (chr10:128548315, GGACT) across all reads in the training data, comparing Nanopolish (left) and SegPore (right). The x-axis represents current in picoamperes (pA).

(B) Histogram of the estimated mean from current signals mapped to the GGACT motif at all annotated m6A-modified genomic locations in the training data, again comparing Nanopolish (left) and SegPore (right). The x-axis represents current in picoamperes (pA).”

(25) Page 18 “SegPore's results show a more pronounced bimodal distribution in the raw signal segment mean, indicating clearer separation of modified and unmodified signals.”

Without knowing the correct values around the target kmer (like Figure 4B), just the more defined bimodal distribution could also indicate the (wrongful) assignment of neighbouring kmer values to this kmer instead, hence this statement lacks some needed support, this is just one interpretation of the possible reasons.

Thank you for the comment. We have added concrete values to Figures 3A and 3B to support this point. Both peaks fall within a reasonable range: the unmodified peak (125 pA) is approximately 1.17 pA away from its reference value of 123.83 pA, and the modified peak (118 pA) is around 7 pA away from the unmodified peak. This shift is consistent with expected signal changes due to RNA modifications (usually less than 10 pA), and the magnitude of the difference suggests that the observed bimodality is more likely caused by true modification events rather than misalignment.

(26) Page 18 “Furthermore, when pooling all reads mapped to m6A-modified locations at the GGACT motif, SegPore showed prominent peaks (Fig. 3B), suggesting reduced noise and improved modification detection.”

I don't think the prominent peaks directly suggest improved detection, this statement is a tad overreaching.

We revised the sentense to the following:

“SegPore exhibited more distinct peaks (Fig. 3B), indicating reduced noise and potentially enabling more reliable modification detection”.

(27) Page18 “(2) direct m6A predictions from SegPore's Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM), which is limited to the six selected 5mers.”

The 'six selected' refers to what exactly? Also, 'why' this is limited to them is also unclear as it is, and it probably would become clearer if it is clearly defined what this refers to.

It is explained the page 16 in the SegPore’s workflow in the original manuscript as follows:

“A key component of SegPore is the 5mer parameter table, which specifies the mean and standard deviation for each 5mer in both modified and unmodified states (Fig. 2A1A). Since the peaks (representing modified and unmodified states) are separable for only a subset of 5mers, SegPore can provide modification parameters for these specific 5mers. For other 5mers, modification state predictions are unavailable.”

e select a small set of 5mers that show clear peaks (modified and unmodified 5mers) in GMM in the m6A site-level data analysis. These 5mers are provided in Supplementary Fig. S2C, as explained in the section “m6A site level benchmark” in the Material and Methods (page 12 in the original manuscript).

“…transcript locations into genomic coordinates. It is important to note that the 5mer parameter table was not re-estimated for the test data. Instead, modification states for each read were directly estimated using the fixed 5mer parameter table. Due to the differences between human (Supplementary Fig. S2A) and mouse (Supplementary Fig. S2B), only six 5mers were found to have m6A annotations in the test data’s ground truth (Supplementary Fig. S2C). For a genomic location to be identified as a true m6A modification site, it had to correspond to one of these six common 5mers and have a read coverage of greater than 20. SegPore derived the ROC and PR curves for benchmarking based on the modification rate at each genomic location….”

We have updated the sentence as follows to increase clarity:

“which is limited to the six selected 5mers that exhibit clearly separable modified and unmodified components in the GMM (see Materials and Methods for details).”

(28) Page 19, Figure 4C, the blue 'Unmapped' needs further explanation. If this means the segmentation+alignment resulted in simply not assigning any segment to a kmer, this would indicate issues in the resulting mapping between raw data and kmers as the data that probably belonged to this kmer is likely mapped to a neighbouring kmer, possibly introducing a bimodal distribution there.

This is due to deletion event in the full alignment algorithm. See Page 8 of SupplementaryNote1:

During the traceback step of the dynamic programming matrix, not every 5mer in the reference sequence is assigned a corresponding raw signal fragment—particularly when the signal’s mean deviates substantially from the expected mean of that 5mer. In such cases, the algorithm considers the segment to be generated by an unknown 5mer, and the corresponding reference 5mer is marked as unmapped.

(29) Page 19, “For six selected m6A motifs, SegPore achieved an ROC AUC of 82.7% and a PR AUC of 38.7%, earning the third-best performance compared with deep leaning methods m6Anet and CHEUI (Fig. 3D).”

How was this selection of motifs made, are these related to the six 5mers in the middle of Supplementary Figure S2? Are these the same six as on page 18? This is not clear to me.

It is the same, see the response to point 27.

(30) Page 21 “Biclustering reveals that modifications at the 6th, 7th, and 8th genomic locations are specific to certain clusters of reads (clusters 4, 5, and 6), while the first five genomic locations show similar modification patterns across all reads.”

This reads rather confusingly. Both the '6th, 7th, and 8th genomic locations' and 'clusters 4,5,6' should be referred to in clearer terms. Either mark them in the figure as such or name them in the text by something that directly matches the text in the figure.

We have added labels to the clusters and genomic locations Figure 4C, and revised the sentence as follows:

“Biclustering reveals that modifications at g6 are specific to cluster C4, g7 to cluster C5, and g8 to cluster C6, while the first five genomic locations (g1 to g5) show similar modification patterns across all reads.”

(31) Page 21, “We developed a segmentation algorithm that leverages the jiggling property in the physical process of DRS, resulting in cleaner current signals for m6A identification at both the site and single-molecule levels.”

Leverages, or just 'takes into account'?

We designed our HHMM specifically based on the jiggling hypothesis, so we believe that using the term “leverage” is appropriate.

(32) Page 21, “Our results show that m6Anet achieves superior performance, driven by SegPore's enhanced segmentation.”

Superior in what way? It barely improves over Nanopolish in Figure 3C and is outperformed by other methods in Figure 3D. The segmentation may have improved but this statement says something is 'superior' driven by that 'enhanced segmentation', so that cannot refer to the segmentation itself.

We revise it as follows in the revised manuscript:

”Our results demonstrate that SegPore’s segmentation enables clear differentiation between m6A-modified and unmodified adenosines.”

(33) Page 21, “In SegPore, we assume a drastic change between two consecutive 5mers, which may hold for 5mers with large difference in their current baselines but may not hold for those with small difference.”

The implications of this assumption don't seem highlighted enough in the work itself and may be cause for falsely discovering bi-modal distributions. What happens if such a 5mer isn't properly split, is there no recovery algorithm later on to resolve these cases?

We agree that there is a risk of misalignment, which can result in a falsely observed bimodal distribution. This is a known and largely unavoidable issue across all methods, including deep neural network–based methods. For example, many of these models rely on a CTC (Connectionist Temporal Classification) layer, which implicitly performs alignment and may also suffer from similar issues.

Misalignment is more likely when the current baselines of neighboring k-mers are close. In such cases, the model may struggle to confidently distinguish between adjacent k-mers, increasing the chance that signals from neighboring k-mers are incorrectly assigned. Accurate baseline estimation for each k-mer is therefore critical—when baselines are accurate, the correct alignment typically corresponds to the maximum likelihood.

We have added the following sentence to the discussion to acknowledge this limitation:

“As with other RNA modification estimation methods, SegPore can be affected by misalignment errors, particularly when the baseline signals of adjacent k-mers are similar. These cases may lead to spurious bimodal signal distributions and require careful interpretation.”

(34) Page 21, “Currently, SegPore models only the modification state of the central nucleotide within the 5mer. However, modifications at other positions may also affect the signal, as shown in Figure 4B. Therefore, introducing multiple states to the 5mer could help to improve the performance of the model.”

The meaning of this statement is unclear to me. Is SegPore unable to combine the information of overlapping kmers around a possibly modified base (central nucleotide), or is this referring to having multiple possible modifications in a single kmer (multiple states)?

We mean there can be modifications at multiple positions of a single 5mer, e.g. C m5C m6A m7G T. We have revised the sentence to:

“Therefore, introducing multiple states for a 5mer to accout for modifications at mutliple positions within the same 5mer could help to improve the performance of the model.”

(35) Page 22, “This causes a problem when apply DNN-based methods to new dataset without short read sequencing-based ground truth. Human could not confidently judge if a predicted m6A modification is a real m6A modification.”

Grammatical errors in both these sentences. For the 'Human could not' part, is this referring to a single person's attempt or more extensively tested?

Thanks for the comment. We have revised the sentence as follows:

“This poses a challenge when applying DNN-based methods to new datasets without short-read sequencing-based ground truth. In such cases, it is difficult for researchers to confidently determine whether a predicted m6A modification is genuine (see Supplmentary Figure S5).”

(36) Page 22, “…which is easier for human to interpret if a predicted m6A site is real.”

"a" human, but also this probably meant to say 'whether' instead of 'if', or 'makes it easier'.

Thanks for the advice. We have revise the sentence as follows:

“One can generally observe a clear difference in the intensity levels between 5mers with an m6A and those with a normal adenosine, which makes it easier for a researcher to interpret whether a predicted m6A site is genuine.”

(37) Page 22, “…and noise reduction through its GMM-based approach…”

Is the GMM providing noise reduction or segmentation?

Yes, we agree that it is not relevant. We have removed the sentence in the revised manuscript as follows:

“Although SegPore provides clear interpretability and noise reduction through its GMM-based approach, there is potential to explore DNN-based models that can directly leverage SegPore's segmentation results.”

(38) Page 23, “SegPore effectively reduces noise in the raw signal, leading to improved m6A identification at both site and single-molecule levels…”

Without further explanation in what sense this is meant, 'reduces noise' seems to overreach the abilities, and looks more like 'masking out'.

Following the reviewer’s suggestion, we change it to ‘mask out'’ in the revised manuscript.

“SegPore effectively masks out noise in the raw signal, leading to improved m6A identification at both site and single-molecule levels.”

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

I recommend the publication of this manuscript, provided that the following comments (and the comments above) are addressed.

In general, the authors state that SegPore represents an improvement on existing software. These statements are largely unquantified, which erodes their credibility. I have specified several of these in the Minor comments section.

Page 5, Preprocessing: The authors comment that the poly(A) tail provides a stable reference that is crucial for the normalisation of all reads. How would this step handle reads that have variable poly(A) tail lengths? Or have interrupted poly(A) tails (e.g. in the case of mRNA vaccines that employ a linker sequence)?

We apologize for the confusion. The poly(A) tail–based normalization is explained in Supplementary Note 1, Section 3.

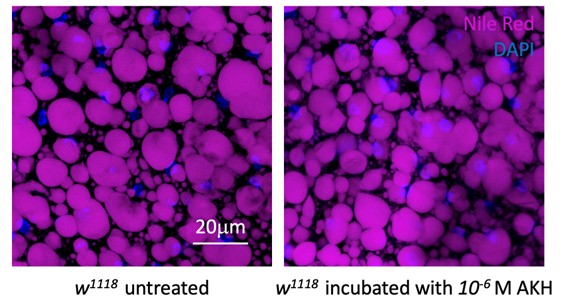

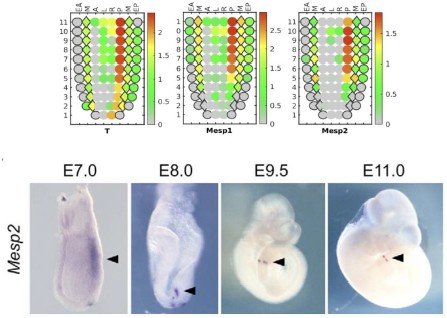

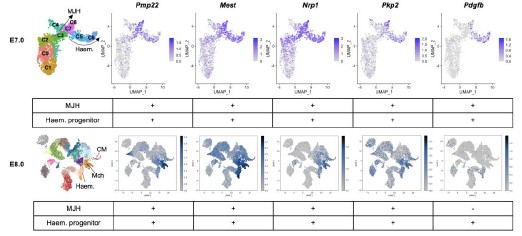

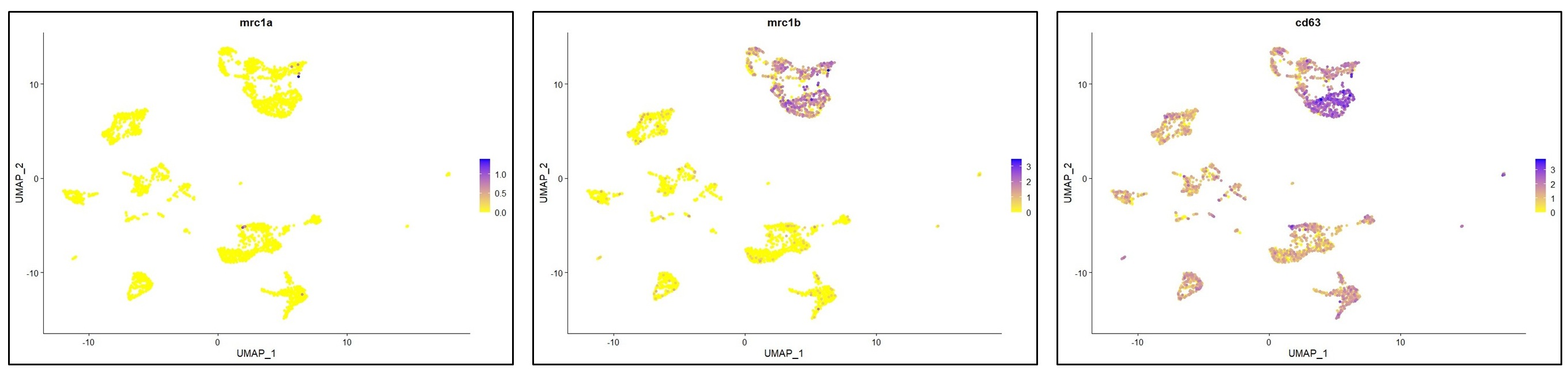

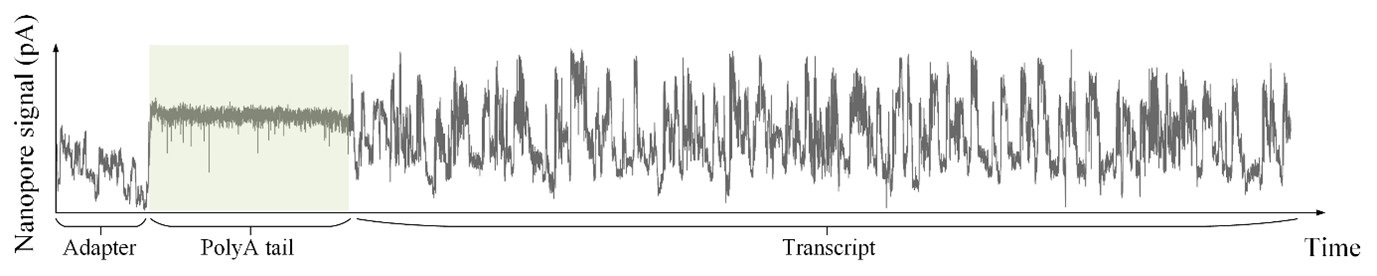

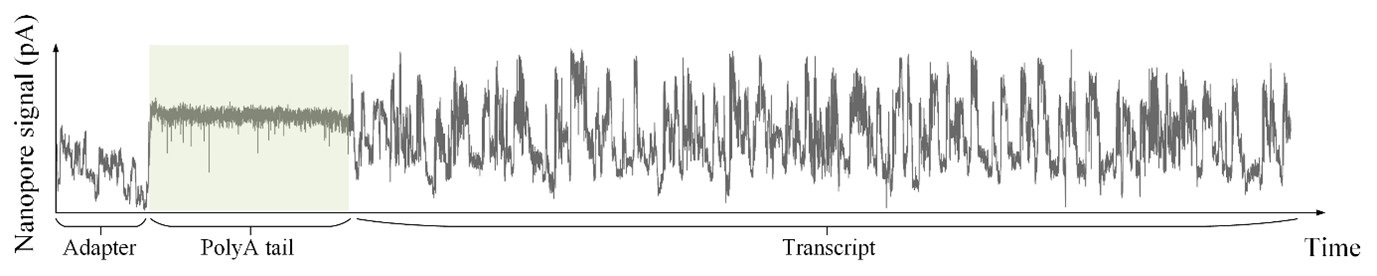

As shown in Author response image 1 below, the poly(A) tail produces a characteristic signal pattern—a relatively flat, squiggly horizontal line. Due to variability between nanopores, raw current signals often exhibit baseline shifts and scaling of standard deviations. This means that the signal may be shifted up or down along the y-axis and stretched or compressed in scale.

Author response image 1.

The normalization remains robust with variable poly(A) tail lengths, as long as the poly(A) region is sufficiently long. The linker sequence will be assigned to the adapter part rather than the poly(A) part.

To improve clarity in the revised manuscript, we have added the following explanation:

“Due to inherent variability between nanopores in the sequencing device, the baseline levels and standard deviations of k-mer signals can differ across reads, even for the same transcript. To standardize the signal for downstream analyses, we extract the raw current signal segments corresponding to the poly(A) tail of each read. Since the poly(A) tail provides a stable reference, we normalize the raw current signals across reads, ensuring that the mean and standard deviation of the poly(A) tail are consistent across all reads. This step is crucial for reducing…..”

We chose to use the poly(A) tail for normalization because it is sequence-invariant—i.e., all poly(A) tails consist of identical k-mers, unlike transcript sequences which vary in composition. In contrast, using the transcript region for normalization can introduce biases: for instance, reads with more diverse k-mers (having inherently broader signal distributions) would be forced to match the variance of reads with more uniform k-mers, potentially distorting the baseline across k-mers.

Page 7, 5mer parameter table: r9.4_180mv_70bps_5mer_RNA is an older kmer model (>2 years). How does your method perform with the newer RNA kmer models that do permit the detection of multiple ribonucleotide modifications? Addressing this comment is crucial because it is feasible that SegPore will underperform in comparison to the newer RNA base caller models (requiring the use of RNA004 datasets).

Thank you for highlighting this important point. For RNA004, we have updated SegPore to ensure compatibility with the latest kit. In our revised manuscript, we demonstrate that the translocation-based segmentation hypothesis remains valid for RNA004, as supported by new analyses presented in the supplementary Figure S4.

Additionally, we performed a new benchmark with f5c and Uncalled4 in RNA004 data in the revised manuscript (Table 2), where SegPore exhibit a better performance than f5c and Uncalled4.

We agree that benchmarking against the latest Dorado models—specifically rna004_130bps_hac@v5.1.0 and rna004_130bps_sup@v5.1.0, which include built-in modification detection capabilities—would provide valuable context for evaluating the utility of SegPore. However, generating a comprehensive k-mer parameter table for RNA004 requires a large, well-characterized dataset. At present, such data are limited in the public domain. Additionally, Dorado is developed by ONT and its internal training data have not been released, making direct comparisons difficult.

Our current focus is on improving raw signal segmentation quality, which are upstream tasks critical to many downstream analyses, including RNA modification detection. Future work may include benchmarking SegPore against models like Dorado once appropriate data become available.

The Methods and Results sections contain redundant information - please streamline the information in these sections and reduce the redundancy. For example, the benchmarking section may be better situated in the Results section.

Following your advice, we have removed redundant texts about the Segmentation benchmark from Materials and Methods in the revised manuscript.

Minor comments

(1) Introduction

Page 3: "By incorporating these dynamics into its segmentation algorithm...". Please provide an example of how motor protein dynamics can impact RNA translocation. In particular, please elaborate on why motor protein dynamics would impact the translocation of modified ribonucleotides differently to canonical ribonucleotides. This is provided in the results, but please also include details in the Introduction.

Following your advice, we added one sentence to explain how the motor protein affect the translocation of the DNA/RNA molecule in the revised manuscript.

“This observation is also supported by previous reports, in which the helicase (the motor protein) translocates the DNA strand through the nanopore in a back-and-forth manner. Depending on ATP or ADP binding, the motor protein may translocate the DNA/RNA forward or backward by 0.5-1 nucleotides.”

As far as we understand, this translocation mechanism is not specific to modified or unmodified nucleotides. For further details, we refer the reviewer to the original studies cited.

Page 3: "This lack of interpretability can be problematic when applying these methods to new datasets, as researchers may struggle to trust the predictions without a clear understanding of how the results were generated." Please provide details and citations as to why researchers would struggle to trust the predictions of m6Anet. Is it due to a lack of understanding of how the method works, or an empirically demonstrated lack of reliability?

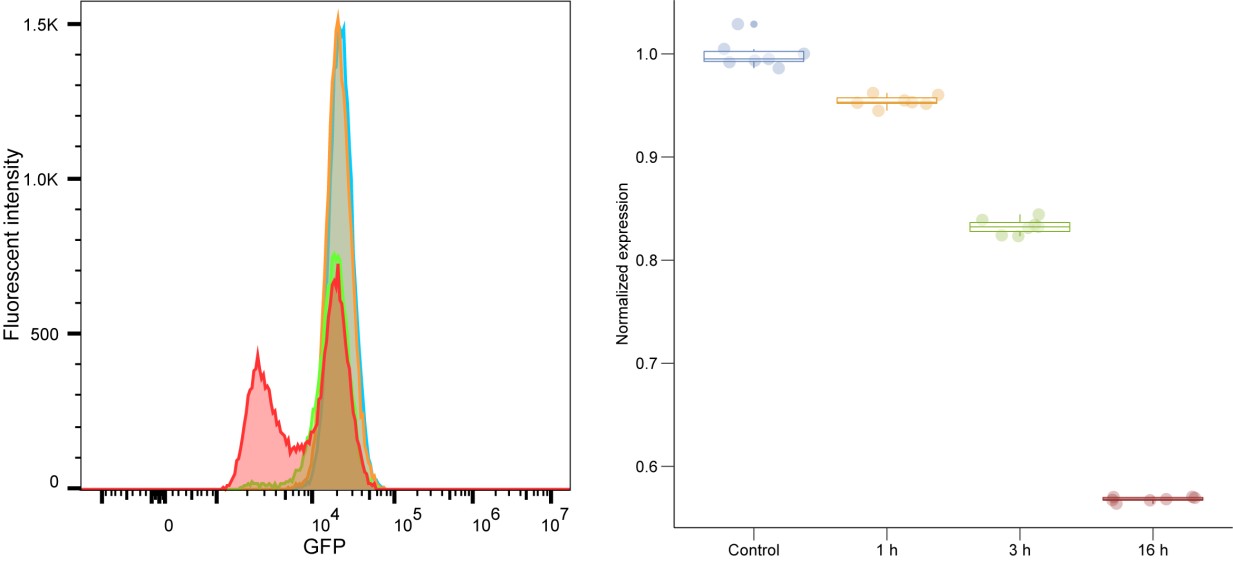

Thank you for pointing this out. The lack of interpretability in deep learning models such as m6Anet stems primarily from their “black-box” nature—they provide binary predictions (modified or unmodified) without offering clear reasoning or evidence for each call.

When we examined the corresponding raw signals, we found it difficult to visually distinguish whether a signal segment originated from a modified or unmodified ribonucleotide. The difference is often too subtle to be judged reliably by a human observer. This is illustrated in the newly added Supplementary Figure S5, which shows Nanopolish-aligned raw signals for the central 5mer GGACT in Figure 4B, displayed both uncolored and colored by modification state (according to the ground truth).

Although deep neural networks can learn subtle, high-dimensional patterns in the signal that may not be readily interpretable, this opacity makes it difficult for researchers to trust the predictions—especially in new datasets where no ground truth is available. The issue is not necessarily an empirically demonstrated lack of reliability, but rather a lack of transparency and interpretability.

We have updated the manuscript accordingly and included Supplementary Figure S5 to illustrate the difficulty in interpreting signal differences between modified and unmodified states.

Page 3: "Instead of relying on complex, opaque features...". Please provide evidence that the research community finds the figures generated by m6Anet to be difficult to interpret, or delete the sections relating to its perceived lack of usability.

See the figure provided in the response to the previous point. We added a reference to this figure in the revised manuscript.

“Instead of relying on complex, opaque features (see Supplementary Figure S5), SegPore leverages baseline current levels to distinguish between…..”

(2) Materials and Methods

Page 5, Preprocessing: "We begin by performing basecalling on the input fast5 file using Guppy, which converts the raw signal data into base sequences.". Please change "base" to ribonucleotide.

Revised as requested.

Page 5 and throughout, please refer to poly(A) tail, rather than polyA tail throughout.

Revised as requested.

Page 5, Signal segmentation via hierarchical Hidden Markov model: "...providing more precise estimates of the mean and variance for each base block, which are crucial for downstream analyses such as RNA modification prediction." Please specify which method your HHMM method improves upon.

Thank you for the suggestion. Since this section does not include a direct comparison, we revised the sentence to avoid unsupported claims. The updated sentence now reads:

"...providing more precise estimates of the mean and variance for each base block, which are crucial for downstream analyses such as RNA modification prediction."

Page 10, GMM for 5mer parameter table re-estimation: "Typically, the process is repeated three to five times until the 5mer parameter table stabilizes." How is the stabilisation of the 5mer parameter table quantified? What is a reasonable cut-off that would demonstrate adequate stabilisation of the 5mer parameter table?