Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study on potassium ion transport by the protein complex KdpFABC from E. coli reveals a 2.1 Å cryo-EM structure of the nanodisc-embedded transporter under turnover conditions. The results confirm that K+ ions pass through a previously identified tunnel that connects the channel-like subunit with the P-type ATPase-type subunit.

Strengths:

The excellent resolution of the structure and the thorough analysis of mutants using ATPase and ion transport measurements help to strengthen new and previous interpretations. The evidence supporting the conclusions is solid, including biochemical assays and analysis of mutants. The work will be of interest to the membrane transporter and channel communities and to microbiologists interested in osmoregulation and potassium homeostasis.

Weaknesses:

There is insufficient credit and citation of previous work.

The manuscript has been thoroughly revised with special attention to acknowledging all past work relevant to the study.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The paper describes the high-resolution structure of KdpFABC, a bacterial pump regulating intracellular potassium concentrations. The pump consists of a subunit with an overall structure similar to that of a canonical potassium channel and a subunit with a structure similar to a canonical ATP-driven ion pump. The ions enter through the channel subunit and then traverse the subunit interface via a long channel that lies parallel to the membrane to enter the pump, followed by their release into the cytoplasm.

Strengths:

The work builds on the previous structural and mechanistic studies from the authors' and other labs. While the overall architecture and mechanism have already been established, a detailed understanding was lacking. The study provides a 2.1 Å resolution structure of the E1-P state of the transport cycle, which precedes the transition to the E2 state, assumed to be the ratelimiting step. It clearly shows a single K+ ion in the selectivity filter of the channel and in the canonical ion binding site in the pump, resolving how ions bind to these key regions of the transporter. It also resolves the details of water molecules filling the tunnel that connects the subunits, suggesting that K+ ions move through the tunnel transiently without occupying welldefined binding sites. The authors further propose how the ions are released into the cytoplasm in the E2 state. The authors support the structural findings through mutagenesis and measurements of ATPase activity and ion transport by surface-supported membrane (SSM) electrophysiology.

Weaknesses:

While the results are overall compelling, several aspects of the work raised questions. First, the authors determined the structure of the pump in nanodiscs under turnover conditions and observed several structural classes, including E1-P, which is detailed in the paper. Two other structural classes were identified, including one corresponding to E2. It is unclear why they are not described in the paper. Notably, the paper considers in some detail what might occur during the E1-P to E2 state transition, but does not describe the 3.1 Å resolution map for the E2 state that has already been obtained. Does the map support the proposed structural changes?

As was seen in previous work by Silberberg et at. (2022), imaging KdpFABC under turnover conditions can produce multiple enzymatic states. We focus on the E1~P state and associated biophysical analyses to provide a clear and concise story that is focused on the conduction pathway for K<sup>+</sup> ions. We continue to work with the cryo-EM data as well as other supporting methodologies and datasets with the goal of producing an additional manuscript that will describe other conformations. The class of particles producing the 3.1 Å structure shown in Fig. 1 – figure suppl. 2 is heterogeneous and thus requires further classification to elucidate conformational changes, as is apparent from the downstream processing of the E1 classes also shown in that figure. We cannot therefore derive any conclusions about the configuration of side chains at the CBS based on this structure. Nevertheless, two previous structures of the E2.Pi state - 7BGY and 7BH2 which were stabilized MgF<sub>4</sub> and BeF<sub>x</sub>, respectively – show the structural change that is described in the paragraph discussing D583A. Given the consistency and relatively high resolution (2.9 and 3.0 Å, respectively) of these two independent structures, we believe that they provide strong support for our proposal for Lys586 acting as a built-in counter ion.

The paper relies on the quantitative activity comparisons between mutants measured using SSM electrophysiology. Such comparisons are notoriously tricky due to variability between SSM chips and reconstitution efficiencies. The authors should include raw traces for all experiments in the supplementary materials, explain how the replicates were performed, and describe the reproducibility of the results. Related to this point above, size exclusion chromatography profiles and reconstitution efficiencies for mutants should be shown to facilitate comparison between measured activities. For example, could it be that the inactive V496R mutant is misfolded and unstable?

Similarly, are the reduced activities of V496W and V496H (and many other mutants) due to changes in the tunnel or poor biochemical properties of these variants? Without these data, the validity of the ion transport measurements is difficult to assess.

To address this concern, we have generated a series of supplementary figures for Figs. 2, 4, 5, and 6, which show all of the raw traces underlying our SSME data (Figure 2 - figure supplements 2-4, Figure 4 - figure supplement 1,Figure 5 - figure supplement 3, Figure 6 - figure supplement 2). We have also included further detail about the experimental protocols, including number and type of replicates, in an expanded "Activity Assays" section of Methods.

In addition, we have included SEC profiles for each of the V496 mutants, which show that they are all well behaved in detergent solution prior to reconstitution (Fig. 4 - figure supplement 1). We are not able to directly document reconstitution efficiencies as it is not practical to separate proteoliposomes from unincorporated protein prior to preparing the sensors used for SSME. Binding currents are seen for several of the inactive mutants (e.g., Q116R in Rb and NH<sub>4</sub> in Fig. 2 - figure supplement 3 and V496R in Fig. 4 - figure supplement 1), which demonstrate that protein is indeed present in the corresponding proteoliposomes even though no sustained transport current is observed.

The authors propose that the tunnel connecting the subunits is filled with water and lacks potassium ions. This is an important mechanistic point that has been debated in the field. It would be interesting to calculate the volume of the tunnel and estimate the number of ions that might be expected in it, given their concentration in bulk. It may also be helpful to provide additional discussion on whether some of the observed densities correspond to bound ions with low occupancy.

As suggested, we calculated the internal volume of the tunnel within KdpA (from the S4 K<sup>+</sup> site to the KdpA/KdpB subunit interface) based on the profile derived from Caver. Based on this volume (4.9 x 10<sup>-25</sup> L), a single K<sup>+</sup> ion within this cavity would correspond to 3.4 M, which is near saturation for a solution of KCl. We added this information together with an acknowledgment of low-occupancy K<sup>+</sup> to the fourth paragraph of the Discussion:

" Fourth, based on the volume of the cavity in KdpA, a single K<sup>+</sup> ion would correspond to a concentration of 3.4 M, suggesting that multiple ions would exceed the solubility limit especially in the absence of counterions. Finally, map densities within the tunnel were either of comparable strength or weaker than surrounding side chain atoms, unlike at S3 and canonical binding sites. Although it is possible that weaker density could represent low occupancy K<sup>+</sup> ions, we favor a mechanism whereby individual K<sup>+</sup> ions occupy the tunnel transiently as they transit between the selectivity filter and the canonical binding site."

In order to make this analysis, we developed a python script to calculate the volume of the tunnel as defined by the Caver software (this software is available via github.com/dls4n/tunnel). In turn, this enabled us to distinguish water molecules that were actually in the tunnel rather than bound more deeply within the structure of KdpA. As a result, we updated the water distribution plot in Fig. 4b. Notably, the 17 water molecules within this cavity would correspond to 57.8 M, which is reasonably near the expected 55 M for an aqueous solution.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

By expressing protein in a strain that is unable to phosphorylate KdpFABC, the authors achieve structures of the active wild-type protein, capturing a new intermediate state, in which the terminal phosphoryl group of ATP has been transferred to a nearby Asp, and ADP remains covalently bound. The manuscript examines the coupling of potassium transport and ATP hydrolysis by a comprehensive set of mutants. The most interesting proposal revolves around the proposed binding site for K+ as it exits the channel near T75. Nearby mutations to charged residues cause interesting phenotypes, such as constitutive uncoupled ATPase activity, leading to a model in which lysine residues can occupy/compete with K+ for binding sites along the transport pathway.

Strengths:

Although this structure is not so different from previous structures, its high resolution (2.1 Å) is impressive and allows the resolution of many new densities in the potassium transport pathway. The authors are judicious about assigning these as potassium ions or water molecules, and explain their structural interpretations clearly. In addition to the nice structural work, the mechanistic work is thorough. A series of thoughtful experiments involving ATP hydrolysis/transport coupling under various pH and potassium concentrations bolsters the structural interpretations and lends convincing support to the mechanistic proposal.

Weaknesses:

The structures are supported by solid membrane electrophysiology. These data exhibit some weaknesses, including a lack of information to assess the rigor and reproducibility (i.e., the number of replicates, the number of sensors used, controls to assess proteoliposome reconstitution efficiency, and the stability of proteoliposome absorption to the sensor).

To address this concern, we have generated a series of supplementary figures for Figs. 2, 4, 5, and 6, which show all of the raw traces underlying our SSME data (Figure 2 - figure supplements 2-4, Figure 4 - figure supplement 1,Figure 5 - figure supplement 3, Figure 6 - figure supplement 2). We have also included further detail about the experimental protocols, including number and type of replicates, in the "Activity Assays" section of Methods.

Reviewing Editor Comments

After discussing the evaluations, the Reviewers and Reviewing Editor have identified the following essential revisions that would need to be addressed to improve the eLife assessment:

(1) Work from others in the field should be adequately described and acknowledged:

(a) Page 2: " A series of X-ray and cryo-EM structures of KdpFABC from E. coli have led to proposals of a novel transport mechanism befitting the unprecedented partnership of these two superfamilies within a single protein complex."

The authors must give credit where credit is due (namely, the Haenelt/Paulino groups having discovered the transport pathway). Why don't they cite Stock et al., where this pathway was described first? The Stokes group proposed an entirely different pathway initially.

Explicit reference to this work has been added to as follows:

“A series of X-ray and cryo-EM structures of KdpFABC from E. coli (Huang et al., 2017; Silberberg et al., 2022, 2021; Stock et al., 2018; Sweet et al., 2021) indicate a novel transport mechanism befitting the unprecedented partnership of these two superfamilies within a single protein complex. As first proposed by Stock et al. (Stock et al., 2018), there is now a consensus that K<sup>+</sup> enters the complex from the extracellular side of the membrane through the selectivity filter of KdpA, but is blocked from crossing the membrane.”

(b) Page 4 " As a result, many previous structures (Huang et al., 2017; Silberberg et al., 2021; Stock et al., 2018; Sweet et al., 2021) feature the S162A mutation to avoid inhibition rather than the fully WT protein used for the current work."

This is not correct. At least the work by Huang et al 2017 and Stock et al 2021 was done without the mutation. This is why the structures also captured the off-cycle state when no E2 inhibitor was used. But in Silberberg et al 2022 the mutant was used, but this is not mentioned

The Q116R mutant was used by Huang et al., but indeed not used for the Stock et al paper. We have replaced the sentence in the manuscript with the following:

“Use of the KdpD knockout strain allowed us to produce WT and mutant protein free from Ser162 phosphorylation.”

(c) Page 4: " In the paper, we report on the most highly populated state (44% of particles)". Exactly the same was also seen in detergent solution, which should be mentioned.

Reference to the Silberberg 2022 paper, where E1~P was the most highly populated state, has been added. The percentage of particles was removed as we are still processing data from the other states, which will we hope will be described in a future manuscript.

(d) Page 7 "Asp583 and Lys586 are two conserved residues on M5 that have previously been shown......indicating that this particular mutation interfered with energy coupling." The lack of discussion of the Haenelt/Paulino 2021 paper, where they have analyzed the coupling in detail and described a proximal binding site where K+ is coordinated by D583 and the neighbouring Phe is very concerning.

To correct this oversight, we made the following changes to the text:

On pg. 7 in the Results section, we refer to the 2005 paper from Bramkamp & Altendorf:

“Consistent with earlier work on this mutant (Bramkamp and Altendorf, 2005), the D583A mutant displayed substantial ATPase activity (30% of WT) but no transport, indicating that this particular mutation interfered with energy coupling.”

At the end of pg. 10 in the Discussion, we revised the paragraph discussing D583 and Lys586 to explicitly refer to the mechanism of transport described in the 2021 paper from Silberberg et al, including proximal and distal binding sites as well as uncoupling due to the D583A mutation.

“Similar to the Glu370/Arg493 charge pair in KdpA, Asp583 and Lys586 are the only charged residues in the membrane core of KdpB. Although they are not seen to interact directly in our structure, they coordinate accessory waters associated with the canonical binding site. Previous molecular dynamics simulations (Silberberg et al., 2021) indicate that Asp583 couples with Phe232 to form a “proximal binding site” for K<sup>+</sup> ions. Based on these simulations, these authors proposed a mechanism whereby neutralization of this site either by ion binding or by D583A substitution served to stimulate ATPase activity. Indeed, earlier work on D583A (Bramkamp and Altendorf, 2005) as well as current data demonstrate uncoupling, in which K<sup>+</sup> independent ATPase activity was observed even though transport was abolished. A plausible explanation for this stimulation is seen in the behavior of Lys586 in previous structures of the E2·Pi state (7BGY and 7BH2) (Sweet et al., 2021). In these structures, M5 undergoes a conformational change that pushes the side chain of Lys586 into the CBS. As a consequence of the D583A mutation, this Lys could be freed to act as a built-in counter ion as in related P-type ATPases ZntA (Wang et al., 2014) and AHA2 (Pedersen et al., 2007). In regard to the proximal binding site and the partnering “distal binding site” on the KdpA-side of the subunit interface, our structure does not show densities at either site and thus does not provide any support for the related mechanism. In any case, in the WT complex it seems likely that Asp583 exerts allosteric control over Lys586 and ensures that its movement into the binding site is coordinated with the transition from E1~P to E2·Pi, thus leading to displacement of K<sup>+</sup> from the CBS and release to the cytoplasm. “

(e) Page 8 " The intersubunit tunnel is arguably one of the most intriguing elements of the KdpFABC complex. Although it has been postulated to conduct K+, experimental evidence has been lacking. "

Incorrect, see Silberberg 2021.

On this point, we beg to differ. Although this 2021 paper shows densities in experimental cryo-EM maps and effects of mutations to residues at the KdpA and KdpB interface, the intra-tunnel transport mechanism is based on computational analysis (MD simulations) and not experimental evidence. We softened the statement to read as follows:

“Although it has been postulated to conduct K<sup>+</sup>, direct experimental evidence has been hard to come by.”

(f) In this context, also f232 is not mentioned anywhere in the text, although depicted in almost all figures.

Phe232 is shown as a point of reference for the KdpA/KdpB subunit interface. We added a reference to Phe232 in the Results section labeled “Intersubunit tunnel” as well as the paragraph in the Discussion addressed in point d) above.

" These densities, which we have modeled as water, are most prevalent near the vestibule, which is the wider part of the tunnel, but then disappear completely at the subunit interface near Phe232, which is the narrowest part of the tunnel and also distinctly hydrophobic (Fig. 4)."

" Previous molecular dynamics simulations (Silberberg et al., 2021) indicate that Asp583 couples with Phe232 to form a “proximal binding site” for K<sup>+</sup> ions."

(g) Page 2 "Later, it was recognized that KdpA belongs to the Superfamily of K+ Transporters (SKT superfamily), which also includes bona fide K+ channels such as KcsA, TrkH and KtrB (Durell et al., 2000). "

KcsA is not a member of the SKT superfamily.

Thanks. This is correct, although the SKT superfamily is believed to have evolved from KcsA. KcsA has been removed from the sentence and a reference added to a review of the SKT superfamily:

“which also includes bona fide K<sup>+</sup> channels such as TrkH and KtrB (Diskowski et al., 2015; Durell et al., 2000).”

(2) Two other structural classes were identified, including one corresponding to E2. It is unclear why they are not described in the paper. Notably, the paper considers in some detail what might occur during the E1-P to E2 state transition, but does not describe the 3.1 Å resolution map for the E2 state that has already been obtained. Does the map support the proposed structural changes?

As was seen in previous work by Silberberg et at. (2022), imaging KdpFABC under turnover conditions can produce multiple enzymatic states. We focus on the E1~P state and associated biophysical analyses to provide a clear and concise story. We continue to work with the cryo-EM data as well as other supporting methodologies and datasets with the goal of producing an additional manuscript that will describe other conformations. The class of particles producing the 3.1 Å structure shown in Fig. 1 – figure suppl. 2 is heterogeneous and thus requires further classification to elucidate conformational changes, as is apparent from the downstream processing of the E1 classes also shown in that figure. We cannot therefore derive any conclusions about the configuration of side chains at the CBS based on this structure. Nevertheless, two previous structures of the E2.Pi state - 7BGY and 7BH2 which were stabilized MgF<sub>4</sub> and BeF<sub>x</sub>, respectively – show the structural change that is described in the paragraph discussing D583A. Given the consistency and relatively high resolution (2.9 and 3.0 Å, respectively) of these two independent structures, we believe that they provide strong support for our proposal for Lys586 acting as a built-in counter ion.

(3) The paper relies on the quantitative activity comparisons between mutants measured using SSM electrophysiology. Such comparisons are notoriously tricky due to variability between SSM chips and reconstitution efficiencies. The authors should include raw traces for all experiments in the supplementary materials, explain how the replicates were performed, and describe the reproducibility of the results.

To address this concern, we have generated supplementary figures for Figs. 2, 4, 5, and 6, which show all of the raw traces underlying our SSME data (Figure 2 - figure supplements 2-4, Figure 4 - figure supplement 1,Figure 5 - figure supplement 3, Figure 6 - figure supplement 2). We have also added a detailed description of replicates, sensor stability and the experimental protocols in the "Activity Assays" section of Methods. In addition, we have highlighted observations of pre-steady state binding currents that were seen for some mutants (e.g., Q116R assayed with Rb<sup>+</sup>, NH<sub>4</sub><sup>+</sup> and Na<sup>+</sup>), in which an initial, transient current response was observed without an ensuing transport current. The depiction of this raw data has allowed us to explain our use of the current response at 1.25 s, after decay of this binding current, as a measure of transport rate. This approach is consistent with recommendations by the manufacturer, as documented in their 2023 publication (Bazzone et al. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1058583).

(4) Related to this point above, size exclusion chromatography profiles and reconstitution efficiencies for mutants should be shown to facilitate comparison between measured activities. For example, could it be that the inactive V496R mutant is misfolded and unstable? Similarly, are the reduced activities of V496W and V496H (and many other mutants) due to changes in the tunnel or poor biochemical properties of these variants? Without these data, the validity of the ion transport measurements is difficult to assess.

We have included SEC profiles for each of the V496 mutants, which show that they are all well behaved in detergent solution prior to reconstitution (Fig. 4 - figure supplement 1). We are not able to directly document reconstitution efficiencies as it is not practical to separate proteoliposomes from unincorporated protein prior to preparing the sensors used for SSME. Binding currents are seen for several of the inactive mutants (e.g., Q116R in Rb and NH<sub>4</sub> in Fig. 2 - figure supplement 3 and V496R in Fig. 4 - figure supplement 1), which demonstrate that protein is indeed present in the corresponding proteoliposomes even though no sustained transport current is observed.

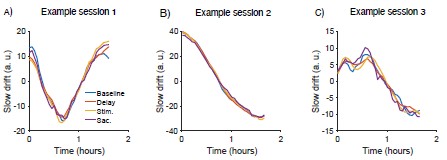

(5) What are the different lines in Figure 1 - Supplement 1, panel G?

This panel depicted a series of SSME traces as an example of the raw data, but has been removed from the revised version given the inclusion of all the raw traces. These new figures include a legend explaining the conditions for each trace.

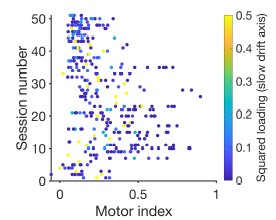

(6) How was the 44 % population of the single-occupancy E1 state estimated (it does not correspond to the number of particles in Figure 1 - Supplement 2.

The calculation of 44% for the E1~P state was premature, given that we are still analyzing the data from the turnover conditions. The revised manuscript simply states that E1~P represented the largest population of particles, which is consistent with this state preceding the rate limiting step of the PostAlbers cycle. Reference is made to the Silberberg 2022 paper, which made a similar observation in a detergent-solubilized sample.

(7) The text states that Km for Q116E is "<10 uM". However, the fitted value is 90 µM in Figure 2e.

This was a typographical error. The text now states that Km for Q116E is <100 M.

(8) The Km values for Rb, NH4, and Na in Figures 2g and h, and Na in Figure 2i do not make sense. They should be removed.

The values for Km were determined by fitting the Michaelis-Menton equation to the data as detailed in the Methods section. Although the curves visually appear rather flat relative to other ions, the fitting generated respectable confidence limits and are therefore defensible in a statistical context. Furthermore, the curves that are shown are based on those values of Km and it would be inappropriate not to cite them.

(9) Figure 3 would benefit from a slice through the protein to orient the viewer.

Thanks for the suggestion. We have added panels to Figs. 3, 5 and 6 in an effort to orient the reader to the site that is depicted.

(10) The differences between R493E, Q, and M do not appear to be significant.

The y-axis is logarithmic which makes a visual comparison difficult. To alleviate this, P values were calculated based on one-way ANOVA analysis are results are indicated in Fig. 3c and 3d. They show that all of the Arg493 mutations have Km significantly higher than WT. Differences between R493E orR493Q and R493Q orR493M are not significant at the p<0.01 level, while the difference between R493E and R493M is highly significant (p<0.001). The associated text on pg. 6 has been slightly modified as follows:

“Changes to Arg493 generally increase Km (lower apparent affinity) without affecting Vmax, with Met substitution having greater effect than charge reversal (R493E).”

(11) Page 5, paragraph 2. Q116R and G232D don't seem like the world's most intuitive mutations. It appears there is a historical reason for looking at these. Could the rationale be explained in the text? (Why R and D specifically?)

These mutations have historical significance, having been generated by random mutagenesis during early characterization of the Kdp system by Epstein and colleagues. A sentence containing relevant references has been added to this paragraph to provide this context:

“Specifically, Q116R and G232D substitutions were initially discovered by random mutagenesis during early characterization of the Kdp system (Buurman et al., 1995; Epstein et al., 1978) and have featured in many follow-up studies (Dorus et al., 2001; Schrader et al., 2000; Silberberg et al., 2021; Sweet et al., 2020; van der Laan et al., 2002).”

Below are the recommendations from each of the reviewers, some of which were not included as essential revisions, but that can also be helpful to further strengthen the manuscript.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

It is essential that the authors correct their selective, incomplete, and in places inappropriate references to work from others in the field.

Specific points:

(1) Page 2: " A series of X-ray and cryo-EM structures of KdpFABC from E. coli have led to proposals of a novel transport mechanism befitting the unprecedented partnership of these two superfamilies within a single protein complex."

The authors must give credit where credit is due (namely, the Haenelt/Paulino groups having discovered the transport pathway). Why don't they cite Stock et al., where this pathway was described first? The Stokes group proposed an entirely different pathway initially.

(2) Page 4 " As a result, many previous structures (Huang et al., 2017; Silberberg et al., 2021; Stock et al., 2018; Sweet et al., 2021) feature the S162A mutation to avoid inhibition rather than the fully WT protein used for the current work."

This is not correct. At least the work by Huang et al 2017 and Stock et al 2021 was done without the mutation. This is why the structures also captured the off-cycle state when no E2 inhibitor was used. But in Silberberg et al 2022 the mutant was used, but this is not mentioned

(3) Page 4: " In the paper, we report on the most highly populated state (44% of particles)". Exactly the same was also seen in detergent solution, which should be mentioned.

(4) Page 7 "Asp583 and Lys586 are two conserved residues on M5 that have previously been shown......indicating that this particular mutation interfered with energy coupling." The lack of discussion of the Haenelt/Paulino 2021 paper, where they have analyzed the coupling in detail and described a proximal binding site where K+ is coordinated by D583 and the neighbouring Phe is very concerning.

(5) Page 8 " The intersubunit tunnel is arguably one of the most intriguing elements of the KdpFABC complex. Although it has been postulated to conduct K+, experimental evidence has been lacking. "

Incorrect, see Silberberg 2021.

(6) In this context, also f232 is not mentioned anywhere in the text, although depicted in almost all figures.

References have been added to address all of these points. See item 1) under Reviewing Editor’s Comments above.

Other points:

(7) Page 2 "Later, it was recognized that KdpA belongs to the Superfamily of K+ Transporters (SKT superfamily), which also includes bona fide K+ channels such as KcsA, TrkH and KtrB (Durell et al., 2000). "

KcsA is not a member of the SKT superfamily.

KcsA has been removed from the sentence and a reference added to a review of the SKT family:

“which also includes bona fide K<sup>+</sup> channels such as TrkH and KtrB (Diskowski et al., 2015; Durell et al., 2000).”

(8) Page 9 " Our demonstration of coupled transport of NH4+ and Rb+ G232D not only confirms that the selectivity filter governs ion selection, but that the pump subunit, KdpB, is relatively promiscuous." Check grammar.

This sentence has been updated as follows:

“Our observation that G232D is capable of coupled transport for NH<sub>4</sub><sup>+</sup and Rb<sup>+</sup> confirms not only that the selectivity filter governs ion selection, but that the pump subunit, KdpB, is relatively promiscuous.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) From an editorial point of view, I suggest a few changes to enhance readability and clarity for non-specialists. A description of the overall transport cycle at the start of the paper (perhaps as a supplementary figure) could help put the work into perspective for general readers who may not be familiar with P-type ATPase mechanisms. It is unclear what "single" and "double" occupancy refer to in the structural classes description. Why is only one structural class described in detail? I would suggest moving the discussion of what is going on with the Nterminus of KdpB to the Results section, where it is described, and shortening the corresponding paragraph in the Discussion. I would furthermore suggest adding a figure that illustrates the proposed regulatory role of the terminus and how phosphorylation might affect it. Otherwise, this section of the results reads very hollow.

A diagram showing the Post-Albers cycle is shown as part of Fig. 1 and is described at the end of the second paragraph. This sentence only mentioned KdpB, which may have caused confusion. We therefore changed the sentence to read as follows:

“Like other P-type ATPases, KdpFABC employs the Post-Albers reaction cycle (Fig. 1) involving two main conformations (E1 and E2) and their phosphorylated states (E1~P and E2-P) to drive transport (Albers, 1967; Post et al., 1969).”

Single and double occupancy was meant to refer to the number of KdpFABC complexes residing in a nanodisc. This can be seen in the class averages in Fig. 1 - figure supplement 2. The legends to Fig. 1 figure supplements 1 and 2 have been revised to explain this observation more explicitly:

"Slight asymmetry of the main peak is consistent with a subpopulation of nanodiscs containing two KdpFABC complexes (Fig. 1 - figure supplement 2)."

and

"A subset of these particles were further classified to generate four main classes representing nanodiscs with a single copy of KdpFABC in either E1 or E2 conformations, nanodiscs with two copies of KdpFABC which were mainly E1 conformation, and junk."

As stated above, the class of particles producing the 3.1 Å structure shown in Fig. 1 – figure suppl. 2 is heterogeneous and requires further classification to elucidate conformational changes, as is apparent from the downstream processing of the E1 classes also shown in that figure. We continue to analyze the cryo-EM data and aim to produce a second manuscript that will include descriptions of other conformations together with the additional biophysical analysis related to their function.

With regard to the N-terminus, we have gone on to generate a truncation of residues 2-9 in KdpB. After expression and purification, this construct remained coupled with ATPase and transport activities similar to WT, which makes proposals of a regulatory effect less compelling. Because of the novelty of observing the N-terminus and the possibility that it plays a subtle role in the kinetics of the cycle not revealed under the current assay conditions, we have retained a brief discussion of this structural observation, but moved it into the Results section as suggested.

"Given the regulatory roles played by N- and C-termini of a variety of other P-type ATPases (Bitter et al., 2022; Cali et al., 2017; Lev et al., 2023; Timcenko et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021), we generated a construct in which residues 2-9 of the N-terminus of KdpB were truncated. However, ATPase and transport activities remained coupled at levels similar to WT, indicating that any functional role of the N-terminus is relatively subtle and not manifested under current assay conditions."

(2) The wording "exceedingly strong densities" seems ambiguous.

We have changed this to “strong” in the Abstract and "exceptionally strong" in the Discussion. The precise values for these densities are shown in density histograms in Fig. 2 – figure supplement 1 and Fig. 5 – figure supplement 2. In the text, the densities are described as follows:

Results sections describing the selectivity filter:

"In fact, this S3 site contains the strongest densities in the entire map, measuring 7.9x higher than the threshold used for Fig. 2a (Fig. 2 – figure suppl. 1a)."

Results section describing the CBS:

"Given that this is the strongest density in KdpB, measuring 5.6x higher than the map densities shown in Fig. 5 (Fig. 5 – figure suppl 2b), we have modeled it as K<sup>+</sup>."

(3) What are the different lines in Figure 1 - Supplement 1, panel G?

This panel depicted a series of SSME traces as an example of the raw data, but has been removed from the revised version given the inclusion of all the raw traces. These new figures include a legend explaining the conditions for each trace.

(4) How was the 44 % population of the single-occupancy E1 state estimated (it does not correspond to the number of particles in Figure 1 - Supplement 2.

The calculation of 44% for the E1~P state was premature, given that we are still analyzing the data from the turnover conditions. We will consider citing an updated value in a future publication once this analysis is complete. The revised manuscript simply states that E1~P represented the largest population of particles, which is consistent with this state preceding the rate limiting step of the Post-Albers cycle. Reference was made to the Silberberg 2022 paper, where a similar observation was made.

(5) Panel 1d is called out of order after panel 1e. Please label Ser 162 in the panel.

The order of these panels have been switched and Ser162 has been labelled as suggested.

(6) Several panels in Figure 1- Supplement 1 are neither referenced nor described.

This figure supplement is referred to multiple times in the Results and the Methods sections of the text as well as in the figure legends. Although each panel is not individually referenced, all of this information is relevant at different points in the manuscript and is explained in the legend.

(7) Is the coordinating geometry for the S3 site consistent with what was previously observed for KcsA and relatives?

The general arrangement of carbonyl atoms in the S3 site is the same in KcsA and KdpA, described by the MacKinnon group as a square antiprism. However, KcsA has strict four-fold symmetry and KdpA does not. As a result, there are small discrepancies between the coordinating geometries in the two structures. This point was made graphically in our original report on the X-ray structure of KdpFABC (Huang et al. 2007, Extended Data Fig. 3), though the positions of the carbonyls are more accurately determined in the current structure due to increased resolution. We added a sentence to the Selectivity Filter section of the Results stating the following:

"This coordination geometry is also consistent with that seen in the K<sup>+</sup> channel KcsA, though the strict four-fold symmetry of that homo-tetramer produces a more regular structure, as indicated by the smaller variance in liganding distance (2.77 Å with s.d. 0.075 Å in 1K4C) and as depicted by Huang et al. in Extended Data Fig. 3 (Huang et al., 2017)."

(8) Label G232D in Figure 2a.

G232 is out of the plane shown in Fig. 2a. However, we have added a label for Cys344 to help identify the selectivity filter strands that are shown. Note, however, that G232 is visible and labeled in Fig. 2 - figure suppl. 1. This has now been noted in the legend for Fig. 2.

(9) The text states that Km for Q116E is "<10 uM". However, the fitted value is 90 uµ in Figure 2e.

This was a typographical error. The text now states that Km for Q116E is <100 M.

(10) The Km values for Rb, NH4, and Na in Figures 2g and h, and Na in Figure 2i do not make sense. They should be removed.

The values for Km were determined by fitting the Michaelis-Menton equation to the data as detailed in the Methods section. Although the curves visually appear rather flat relative to other ions, the fitting generated respectable confidence limits and are therefore defensible in a statistical context. Furthermore, the curves that are shown are based on those values of Km and it would be inappropriate not to cite them.

(11) Figure 3 would benefit from a slice through the protein to orient the viewer.

Thank you for the suggestion. We have added panels to Figs. 3, 5 and 6 in an effort to orient the reader to the site that is depicted.

(12) The differences between R493E, Q, and M do not appear to be significant.

The y-axis is logarithmic which makes a visual comparison difficult. To alleviate this, P values were calculated based on one-way ANOVA analysis are results are indicated in Fig. 3c and 3d. They show that all of the Arg493 mutations have Km significantly higher than WT. Differences between R493E orR493Q and R493Q orR493M are not significant at the p<0.01 level, while the difference between R493E and R493M is highly significant (p<0.001). The associated text on pg. 6 has been slightly modified as follows:

“Changes to Arg493 generally increase Km (lower apparent affinity) without affecting Vmax, with Met substitution having greater effect than charge reversal (R493E).”

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

Overall, the text was very clear, experiments were rationalized well, and conclusions were justified. A few small comments:

(1) Page 5, paragraph 2. Q116R and G232D don't seem like the world's most intuitive mutations. It appears there is a historical reason for looking at these. Could the rationale be explained in the text? (Why R and D specifically?)

These mutations are of historical importance, having been generated by random mutagenesis during early characterization of the Kdp system. A sentence containing relevant references has been added to this paragraph to provide this information as context:

“Specifically, Q116R and G232D substitutions were initially discovered by random mutagenesis during early characterization of the Kdp system (Buurman et al., 1995; Epstein et al., 1978) and have featured in many follow-up studies (Dorus et al., 2001; Schrader et al., 2000; Silberberg et al., 2021; Sweet et al., 2020; van der Laan et al., 2002).”

(2) Typo: page 14, "diluted"

This typo has been corrected.

(3) The Methods section for SSM electrophysiology could use some additional description of how the data/statistics were collected. How many replicates? Were all replicates from a single sensor/ were multiple sensors examined? Were controls done to test whether the same number of liposomes remain absorbed by the sensor over the length of the experiment?

We have extended our description of experimental protocols in the "Activity Assays" section of Methods. This includes the number and type of replicates as well as a discussion of binding currents that were seen for some mutants. Furthermore, a new series of supplementary figures for Figs. 2, 4, 5, and 6 show all of the raw traces for the SSME measurements (Figure 2 - figure supplements 2-4, Figure 4 - figure supplement 1, Figure 5 - figure supplement 3, Figure 6 - figure supplement 2).

We have included SEC profiles for each of the V496 mutants, which show that they are all well behaved in detergent solution prior to reconstitution (Fig. 4 - figure supplement 1). We are not able to directly document reconstitution efficiencies as it is not practical to separate proteoliposomes from unincorporated protein prior to preparing the sensors used for SSME. Binding currents are seen for several of the inactive mutants (e.g., Q116R in Rb and NH<sub>4</sub> in Fig. 2 - figure supplement 3 and V496R in Fig. 4 - figure supplement 1), which demonstrate that protein is indeed present in the corresponding proteoliposomes even though no sustained transport current is observed.