Author Response:

Reviewer #1:

This is a very interesting study that examines the neural processes underlying age-related changes in the ability to prioritize memory for value information. The behavioral results show that older subjects are better able to learn which information is valuable (i.e., more frequently presented) and are better at using value to prioritize memory. Importantly, prioritizing memory for high-value items is accompanied by stronger neural responses in the lateral PFC, and these responses mediate the effects of age on memory.

Strengths of this paper are the large sample size and the clever learning tasks. The results provide interesting insights into potential neurodevelopmental changes underlying the prioritization of memory.

There are also a few weaknesses:

First, the effects of age on repetition suppression in the parahippocampal cortex are relatively modest. It is not clear why repetition suppression effects should only be estimated using the first and last but not all presentations. The consideration of linear and quadratic effects of repetition number could provide a more reliable estimate and provide insights into age-related differences in the dynamics of frequency learning across multiple repetitions.

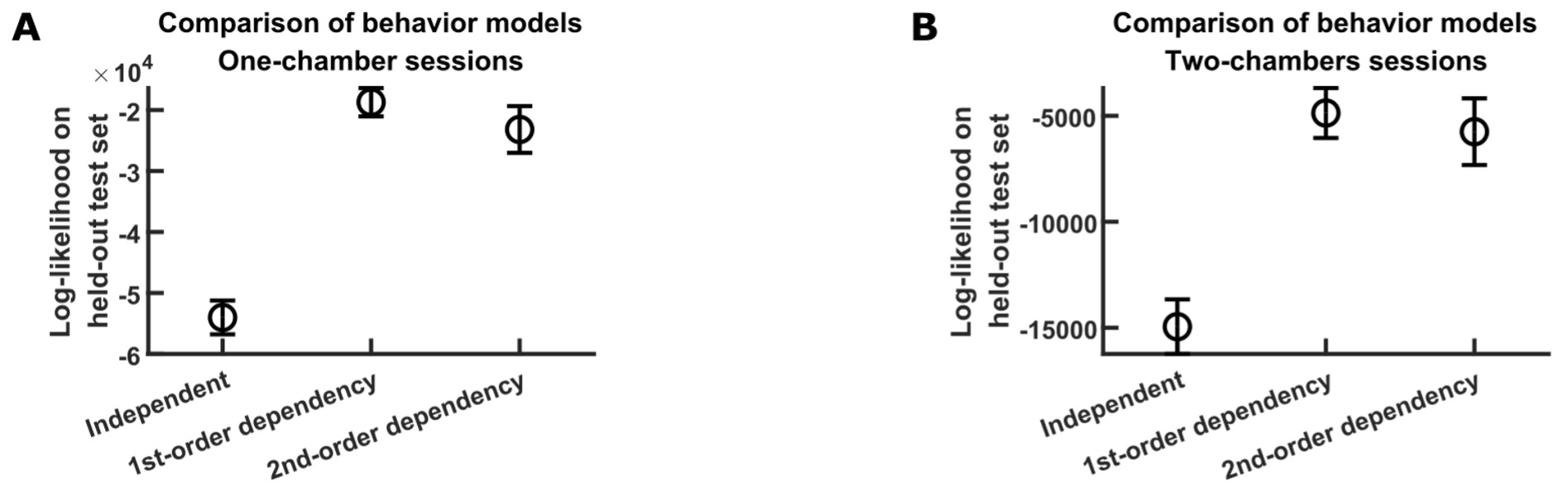

Thank you for this helpful suggestion. As recommended, we have now computed neural activation within our parahippocampal region of interest not just for the first and last appearance of each item during frequency learning, but for all appearances. Specifically we extended our repetition suppression analysis described in the manuscript to include all image repetitions (p. 36 - 37). Our new methods description reads:

“For each stimulus in the high-frequency condition, we examined repetition suppression by measuring activation within a parahippocampal ROI during the presentation of each item during frequency-learning. We defined our ROI by taking the peak voxel (x = 30, y = -39, z = -15) from the group-level first > last item appearance contrast for high-frequency items during frequency-learning and drawing a 5 mm sphere around it. This voxel was located in the right parahippocampal cortex, though we observed widespread and largely symmetric activation in bilateral parahippocampal cortex. To encompass both left and right parahippocampal cortex within our ROI, we mirrored the peak voxel sphere. For each participant, we modeled the neural response to each appearance of each item using the Least Squares-Separate approach (Mumford et al., 2014). Each first-level model included a regressor for the trial of interest, as well as separate regressors for the onsets of all other items, grouped by repetition number (e.g., a regressor for item onsets on their first appearance, a regressor for item onsets on their second appearance, etc.). Values that fell outside five standard deviations from the mean level of neural activation across all subjects and repetitions were excluded from subsequent analyses (18 out of 10,320 values; .01% of observations). In addition to examining neural activation as a function of stimulus repetition, we also computed an index of repetition suppression for each high-frequency item by computing the difference in mean beta values within our ROI on its first and last appearance.”

As suggested, we ran a mixed effects model examining the influence of linear and quadratic age and linear and quadratic repetition number on neural activation. In line with our whole-brain analysis, we observed a robust effect of linear and quadratic repetition number, suggesting that neural activation decreased non-linearly across stimulus repetitions. In addition, we observed significant interactions between our age and repetition number terms, suggesting that repetition suppression increased into early adulthood. Thus, although the relation we observed between age and repetition suppression is modest, the results from our new analyses suggest it is robust. Because these results largely aligned with the pattern of age-related change we observed in our analysis of repetition suppression indices, we continued to use that compressed metric in subsequent analyses looking at relations with behavior. However, we have updated our results section to include the full analysis taking into account all item repetitions, as suggested. Our updated manuscript now reads (p. 9):

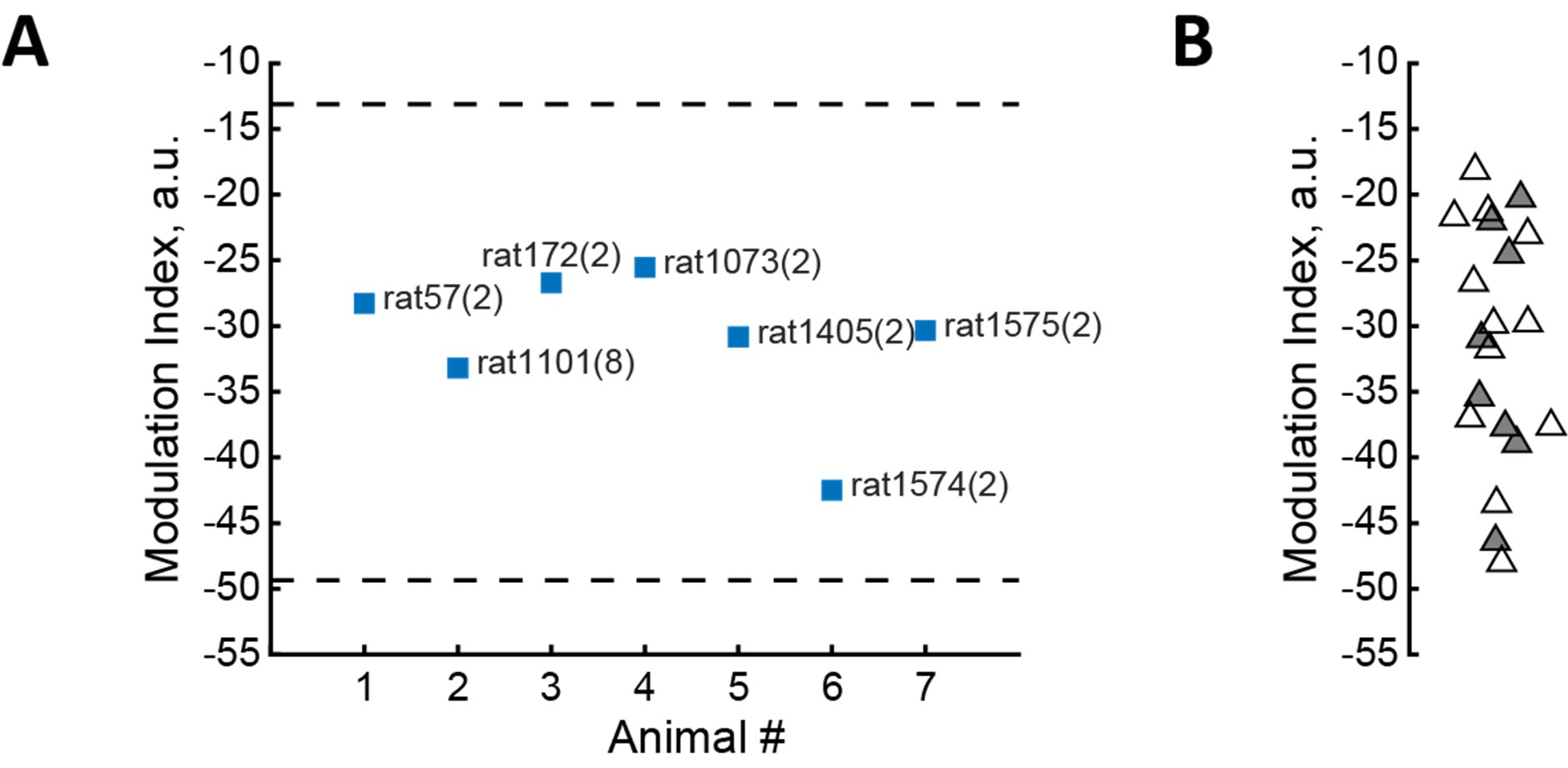

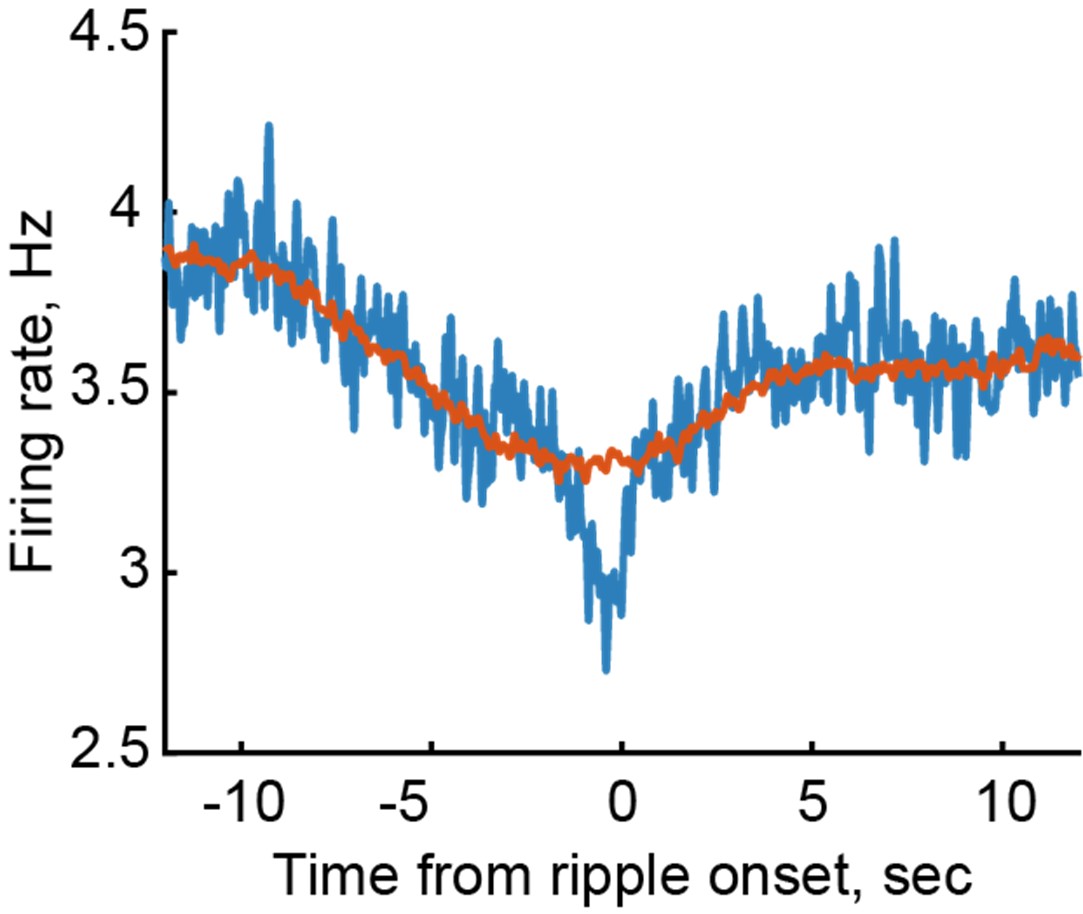

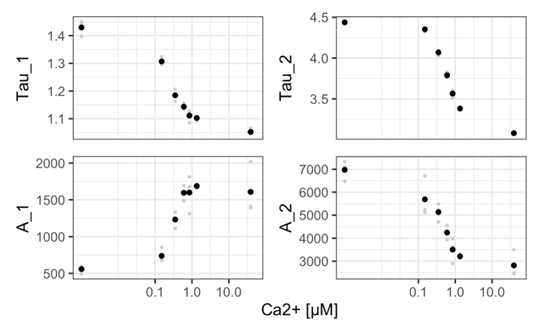

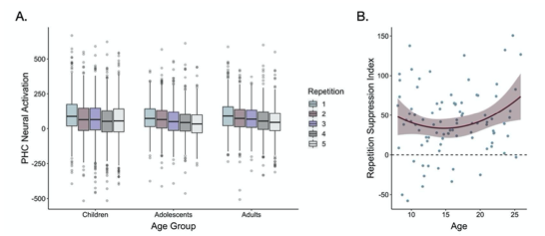

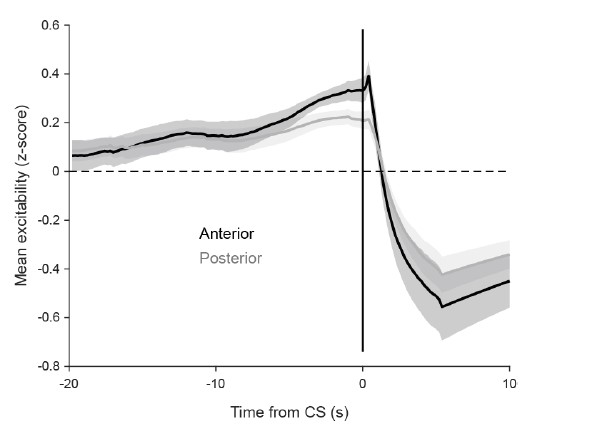

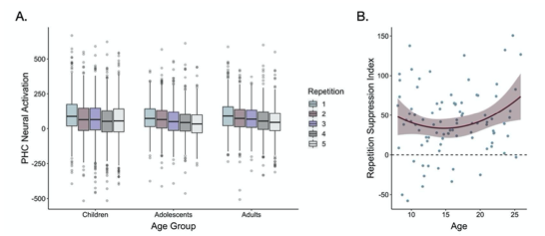

“We next examined whether repetition suppression in the parahippocampal cortex changed with age. We defined a parahippocampal region of interest (ROI) by drawing a 5mm sphere around the peak voxel from the group-level first > last appearance contrast (x = 30, y = -39, z = -15), and mirrored it to encompass both right and left parahippocampal cortex (Figure 2C). For each participant, we modeled the neural response to each appearance of each high-frequency item. We then examined how neural activation changed as a function of repetition number and age. To account for non-linear effects of repetition number, we included linear and quadratic repetition number terms. In line with our whole-brain analysis, we observed a main effect of repetition number, F(1, 5016.0) = 30.64, p < .001, indicating that neural activation within the parahippocampal ROI decreased across repetitions. Further, we observed a main effect of quadratic repetition number, F(1, 9881.0) = 7.47, p = .006, indicating that the reduction in neural activity was greatest across earlier repetitions (Fig 3A). Importantly, the influence of repetition number on neural activation varied with both linear age, F(1, 7267.5) = 7.2, p = .007 and quadratic age , F(1, 7260.8) = 6.9, p = .009. Finally, we also observed interactions between quadratic repetition number and both linear and quadratic age (ps < .026). These age-related differences suggest that repetition suppression was greatest in adulthood, with the steepest increases occurring from late adolescence to early adulthood (Figure 3).”

"For each participant for each item, we also computed a “repetition suppression index” by taking the difference in mean beta values within our ROI on each item’s first and last appearance (Ward et al., 2013). These indices demonstrated a similar pattern of age- related variance — we found that the reduction of neural activity from the first to last appearance of the items varied positively with linear age, F(1, 78.32) = 3.97, p = .05, and negatively with quadratic age, F(1, 77.55) = 4.8, p = .031 (Figure 3B). Taken together, our behavioral and neural results suggest that sensitivity to the repetition of items in the environment was prevalent from childhood to adulthood but increased with age.”

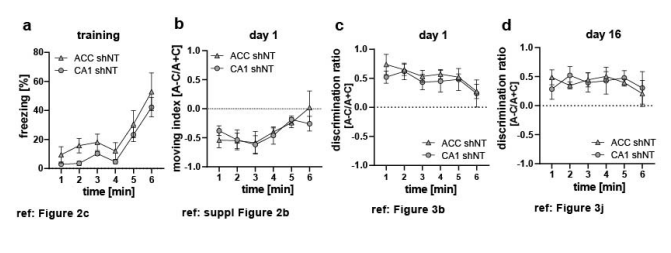

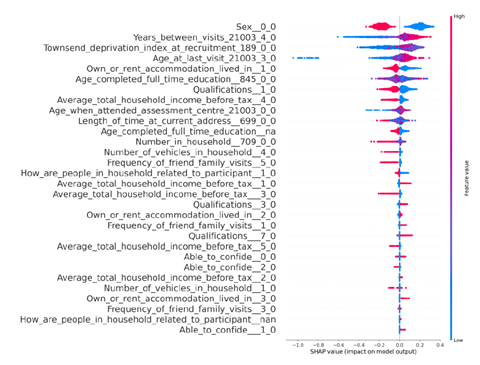

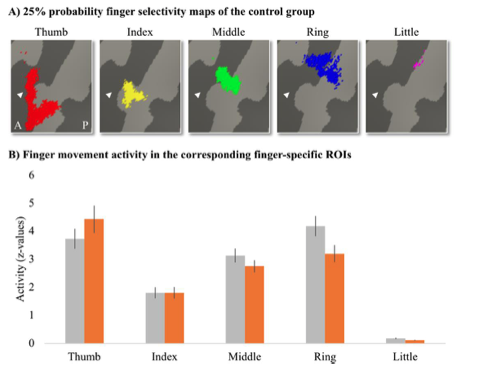

In addition, in the main text on p. 10, we have now included the suggested scatter plot (see new Fig. 3B, below) as well as a modified version of our previous figure S2 to show neural activation across all repetitions in the parahippocampal cortex (see new Fig 3A). We thank the reviewer for this helpful suggestion, as we believe these new figures much more clearly illustrate the repetition suppression effects we observed during frequency learning.

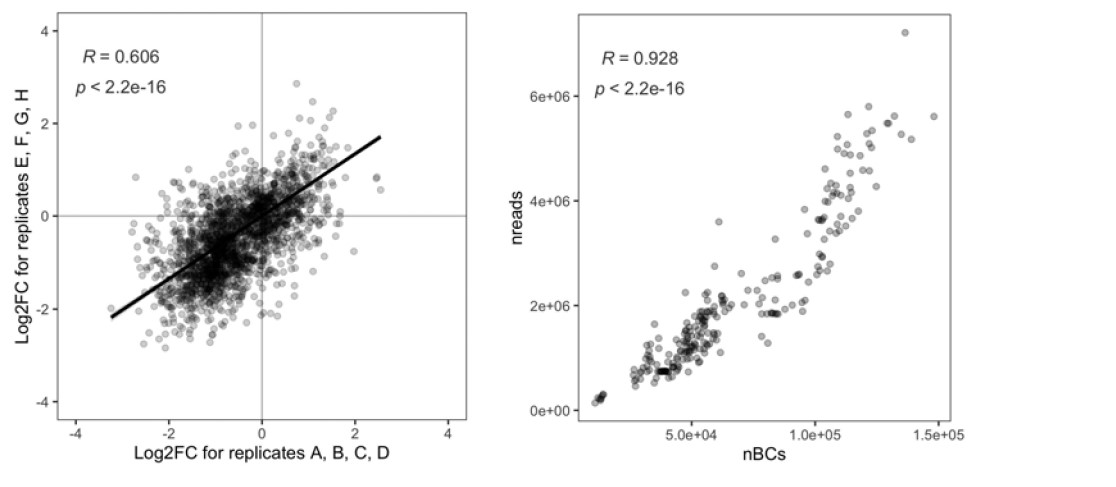

Fig 3. (A) Neural activation within a bilateral parahippocampal cortex ROI decreased across stimulus repetitions both linearly, F(1, 5015.9) = 30.64, p < .001, and quadratically, F(1, 9881.0) = 7.47, p = .006. Repetition suppression increased with linear age, F(1, 7267.5) = 7.2, p = .007, and quadratic age F(1, 7260.8) = 6.9, p = .009. The horizontal black lines indicate median neural activation values. The lower and upper edges of the boxes indicate the first and third quartiles of the grouped data, and the vertical lines extend to the smallest value no further than 1.5 times the interquartile range. Grey dots indicate data points outside those values. (B) The decrease in neural activation in the bilateral PHC ROI from the first to fifth repetition of each item also increased with both linear age, F(1, 78.32) = 3.97, p = .05, and quadratic age, F(1, 77.55) = 4.8, p = .031.

Second, the behavioral data show effects of age on both initial frequency learning and the effects of item frequency on memory. It is not clear whether the behavioral findings reflect the effects of age on the ability to use value information to prioritize memory or simply better initial learning of value-related information on older subjects.

Thank you for raising this important point. Indeed, one of our main findings is that older participants are better both at learning the structure of their environments and also at using structured knowledge to strategically prioritize memory. In our original manuscript, we described results of a model that included participants’ explicit frequency reports as a predictor of memory. Model comparison revealed that participants’ frequency reports — which we interpret as reflecting their beliefs about the structure of the environment — predicted memory more strongly than the item’s true frequency. In other words, participants’ beliefs about the structure of the environment (even if incorrect) more strongly influenced their memory encoding than the true structure of the environment. Critically, however, frequency reports interacted with age to predict memory (Fig 8). Even when we accounted for age-related differences in knowledge of the structure of the environment, older participants demonstrated a stronger influence of frequency on memory, suggesting they were better able to use their beliefs to control subsequent associative encoding. We have now clarified our interpretation of this model in our discussion on p. 23:

“Importantly, though we observed age-related differences in participants’ learning of the structure of their environment, the strengthening of the relation between frequency reports and associative memory with increasing age suggests that age differences in learning cannot fully account for age differences in value-guided memory. Even when accounting for individual differences in participants’ explicit knowledge of the structure of the environment, older participants demonstrated a stronger relation between their beliefs about item frequency and associative memory, suggesting that they used their beliefs to guide memory to a greater degree than younger participants.”

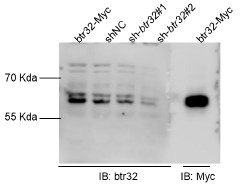

As noted by the reviewer, however, our initial memory analysis did not account for age-related differences in participants’ initial, online learning of item frequency, and our neural analyses further did not account for age differences in explicit frequency reports. We have now run additional control analyses to account for the potential influence of individual differences in frequency learning on associative memory. Specifically, for each participant, we computed three metrics: 1.) their overall accuracy during frequency-learning, 2.) their overall accuracy for the last presentation of each item during frequency-learning (as suggested by Reviewer 2), and 3.) the mean magnitude of the error in their frequency reports. We then included these metrics as covariates in our memory analyses.

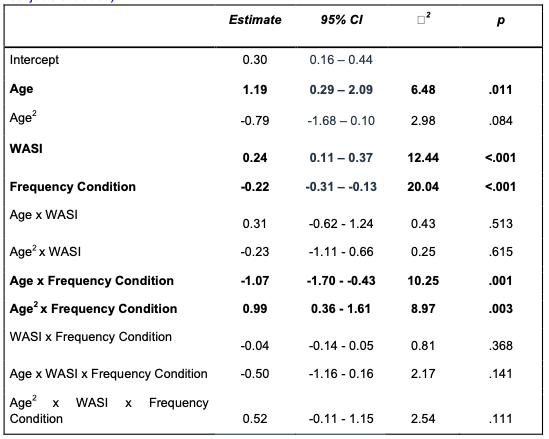

When we include these control variables in our model, we continue to observe a robust effect of frequency condition (p < .001) as well as robust interactions between frequency condition and linear and quadratic age (ps < .003) on associative memory accuracy. We also observed a main effect of frequency error magnitude on memory accuracy (p < .001). Here, however, we no longer observe main effects of age or quadratic age on overall memory accuracy. Given the relation we observed between frequency error magnitudes and age, the results from this model suggests that there may be age-related improvements in overall memory that influence both memory for associations as well as learning of and memory for item frequencies. The fact that age no longer relates to overall memory when controlling for frequency error magnitudes suggest that age-related variance in memory for item frequencies and memory for associations are strongly related within individuals. Importantly, however, age-related variance in memory for item frequencies did not explain age-related variance in the influence of frequency condition on associative memory, suggesting that there are developmental differences in the use of knowledge of environmental structure to prioritize valuable information in memory that persist even when controlling for age-related differences in initial learning of environmental regularities. Given the importance of this analysis in elucidating the relation between the learning of environmental structure and value-guided memory, we have now updated the results in the main text of our manuscript to include them. Specifically, on p. 13, we now write:

“Because we observed age-related differences in participants’ online learning of item frequencies and in their explicit frequency reports, we further examined whether these age differences in initial learning could account for the age differences we observed in associative memory. To do so, we ran an additional model in which we included each participant’s mean frequency learning accuracy, mean frequency learning accuracy on the last repetition of each item, and explicit report error magnitude as covariates. Here, explicit report error magnitude predicted overall memory performance, χ2(1) =13.05, p < .001, and we did not observe main effects of age or quadratic age on memory performance (ps > .20). However, we continued to observe a main effect of frequency condition, χ2(1) = 19.65 p < .001, as well as significant interactions between frequency condition and both linear age χ2(1) = 10.59, p = .001, and quadratic age χ2(1) = 9.15, p = .002. Thus, while age differences in initial learning related to overall memory performance, they did not account for age differences in the use of environmental regularities to strategically prioritize memory for valuable information.”

In addition, as suggested by the reviewer, we also included the three covariates as control variables in our mediation analysis. When controlling for online frequency learning and explicit frequency report errors, PFC activity continued to mediate the relation between age and memory difference scores. We have now included these results on p. 16 - 17 of the main text:

“Further, when we included quadratic age, WASI scores, online frequency learning accuracy, online frequency learning accuracy on the final repetition of each item, and mean explicit frequency report error magnitudes as control variables in the mediation analysis, PFC activation continued to mediate the relation between linear age and memory difference scores (standardized indirect effect: .56, 95% confidence interval: [.06, 1.35], p = .023; standardized direct effect; 1.75, 95% confidence interval: [.12, .3.38], p = .034).”

We also refer to these analyses when we interpret our findings in our discussion. On p. 23, we write:

“In addition, we continued to observe a robust interaction between age and frequency condition on associative memory, even when controlling for age-related change in the accuracy of both online frequency learning and explicit frequency reports. Thus, though we observed age differences in the learning of environmental regularities and in their influence on subsequent associative memory encoding, our developmental memory effects cannot be fully explained by differences in initial learning.”

We thank the reviewer for this constructive suggestion, as we believe these control analyses strengthen our interpretation of age differences in both the learning and use of environmental regularities to prioritize memory.

Reviewer #2:

Nussenbaum and Hartley provide novel neurobehavioral evidence of how individuals differentially use incrementally acquired information to guide goal-relevant memory encoding, highlighting roles for the medial temporal lobe during frequency learning, and the lateral prefrontal cortex for value-guided encoding/retrieval. This provides a novel behavioral phenomenology that gives great insight into the processes guiding adaptive memory formation based on prior experience. However, there were a few weaknesses throughout the paper that undermined an overall mechanistic understanding of the processes.

First, there was a lack of anatomical specificity in the discussion and interpretation of both prefrontal and striatal targets, as there is great heterogeneity across these regions that would infer very different behavioral processes.

We agree with the reviewer that our introduction and discussion would benefit from more anatomical granularity, and we did indeed have a priori predictions about more specific neural regions that might be involved in our task.

First, we expected that both the ventral and dorsal striatum might be responsive to stimulus value across our age range. Prior work has suggested that activity in the ventral striatum often correlates with the intrinsic value of a stimulus, whereas activity in the dorsal striatum may reflect goal-directed action values (Liljeholm & O’Doherty, 2012). In our task, we expected that high-frequency items may acquire intrinsic value during frequency-learning that is then reflected in the striatal response to these items during encoding. However, because participants were not rewarded when they encountered these images, but rather incentivized to encode associations involving them, we hypothesized that the dorsal striatum may represent the value of the ‘action’ of remembering each pair. In line with this prediction, the dorsal striatum, and the caudate in particular, have also been shown to be engaged during value-guided cognitive control (Hikosaka et al., 2014; Insel et al., 2017).

We have now revised our introduction to include greater specificity in our anatomical predictions on p. 3:

“When individuals need to remember information associated with previously encountered stimuli (e.g., the grocery store aisle where an ingredient is located), frequency knowledge may be instantiated as value signals, engaging regions along the mesolimbic dopamine pathway that have been implicated in reward anticipation and the encoding of stimulus and action values. These areas include the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the ventral and dorsal striatum (Adcock et al., 2006; Liljeholm & O’Doherty, 2012; Shigemune et al., 2014).”

Though we initially predicted that encoding of high-value information would be associated with increased activation in both the ventral and dorsal striatum, the activation we observed was largely within the dorsal striatum, and specifically, the caudate. We have now revised our discussion accordingly on p. 26:

“Though we initially hypothesized that both the ventral and dorsal striatum may be involved in encoding of high-value information, the activation we observed was largely within the dorsal striatum, a region that may reflect the value of goal-directed actions (Liljeholm & O’Doherty, 2012). In our task, rather than each stimulus acquiring intrinsic value during frequency-learning, participants may have represented the value of the ‘action’ of remembering each pair during encoding.”

Second, while the ventromedial PFC often reflects value, given the control demands of our task, we expected to see greater activity in the dorsolateral PFC, which is often engaged in tasks that require the implementation of cognitive control (Botvinick & Braver, 2015). Thus, we hypothesized that individuals would show increased activation in the dlPFC during encoding of high- vs. low-value information, and that this activation would vary as a function of age. We have now clarified this hypothesis on p. 3:

“Value responses in the striatum may signal the need for increased engagement of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) (Botvinick & Braver, 2015), which supports the implementation of strategic control.”

In our discussion, we review disparate findings in the developmental literature and discuss factors that may contribute to these differences across studies. For example, in our discussion of Davidow et al. (2016), we highlight differences between their task design and the present study, focusing on how their task involved immediate receipt of reward at the time of encoding, while our task incentivized memory accuracy. We further note that studies that involve reward delivery at the time of encoding may engage different neural pathways than those that promote goal-directed encoding. Beyond Davidow et al. (2016), there are no other neuroimaging studies that examine the influence of reward on memory across development. Thus, we cannot relate our present neural findings to prior work on the development of value-guided memory. As we note in our discussion (p. 28), “Further work is needed to characterize both the influence of different types of reward signals on memory across development, as well as the development of the neural pathways that underlie age-related change in behavior.”

Second, age-related differences in neural activation emerged both during the initial frequency learning as well as during memory-guided adaptive encoding. While data from this initial phase was used to unpack the behavioral relationships on adaptive memory, a major weakness of the paper was not connecting these measures to neural activity during memory encoding/retrieval. This would be especially relevant given that both implicit and explicit measures of frequency predicted subsequent performance, but it is unclear which of these measures was guiding lateral PFC and caudate responses.

Thank you for this valuable suggestion. We agree that it would be interesting to link frequency- learning behavior to neural activity at encoding. As such, we have now conducted additional analyses to explore these relations.

In the original version of our manuscript, we examined behavior at the item level through mixed- effects models, and neural activation during encoding at the participant level. Thus, to examine the relation between frequency-learning metrics and neural activation at encoding, we created two additional participant-level metrics. For each participant we computed their average repetition suppression index, and a measure of frequency distance. The average repetition suppression index reflects the overall extent to which the participant demonstrated repetition suppression in response to the fifth presentation of the high-frequency items, and is computed by averaging each participant’s repetition suppression indices across items. We hypothesized that participants who demonstrated the greatest degree of repetition suppression might be the most sensitive to the difference between the 1- and 5-frequency items, and therefore, show the greatest differences in striatal and PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value information. The frequency distance metric reflects the average distance between participants’ explicit frequency reports for items that appeared once and items that appeared five times, and is computed by averaging their explicit frequency reports for items in each frequency condition, and then subtracting the average reports in the low-frequency condition from those in the high- frequency condition. We hypothesized that participants with the largest frequency distances might similarly be the most sensitive to the difference between the 1- and 5-frequency items, and therefore, show the greatest differences in striatal and PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value information.

We first wanted to confirm that the relations we observed between repetition suppression, frequency reports, and age, could also be observed at the participant level. In line with our prior, behavioral analyses, we found that age related to both mean repetition suppression indices (marginally; linear age: p = .067; quadratic age: p = .042); and frequency distances (linear and quadratic age: ps < .001).

In addition, we further tested whether these two metrics related to memory performance. In contrast to our item-level findings, we did not observe a significant relation between repetition suppression indices and memory (p = .83). We did observe an effect of frequency distance on memory performance. Specifically, we observed significant interactions between frequency distance and age (p = .014) and frequency distance and quadratic age (p = .021) on memory difference scores, such that the influence of frequency distance on memory difference scores increased with increasing age from childhood to adolescence.

We next examined how mean repetition suppression indices and frequency distances related to differential neural activation during encoding of high- and low-value pairs. In line with our memory findings, we did not observe any significant relations between mean repetition suppression indices and neural activation in the caudate or prefrontal cortex during encoding (ps > .15).

Frequency distance did not relate to caudate activation during encoding nor did we observe a frequency distance x age interaction effect (ps > .16). Frequency distance did, however, relate to differential PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value pairs. Specifically, we observed a main effect of frequency distance on PFC activation (p = .0012), such that participants whose explicit reports of item frequency, were on average, more distinct across frequency conditions, demonstrated increased PFC activation during encoding of pairs involving high- vs. low-frequency items. Interestingly, when we included frequency distance in our model, we no longer observed a significant effect of age on differential PFC activation, nor did we observe a significant frequency distance x age interaction (ps > .13). These findings suggest that PFC activation during encoding may have, in part, reflected participants’ beliefs about the structure of the environment, with participants demonstrating stronger differential engagement of control processes across conditions when their representations of the conditions themselves were more distinct.

Finally, we examined how age, frequency distance, and PFC activation related to memory difference scores. Here, even when controlling for both frequency distance and PFC activation, we continued to observe main effects of age and quadratic age on memory difference scores (linear age: p = .006; quadratic age: p = .001). In line with our analysis of the relation between frequency reports and memory, these results suggest that age-related variance in value-guided memory may depend on both knowledge of the structure of the environment and use of that knowledge to effectively control encoding.

We have now added these results to our manuscript on p. 13 - 14. We write:

“Given the relations we observed between memory and both repetition suppression and frequency reports, we examined whether they related to neural activation in both our caudate and PFC ROI during encoding. To do so, we computed each participant’s average repetition suppression index, and their “frequency distance” — or the average difference in their explicit reports for items in the high- and low-frequency conditions. We expected that participants with greater average repetition suppression indices and greater frequency distances represented the high- and low-frequency items as more distinct from one another and therefore would show greater differences in neural activation at encoding across frequency conditions. In line with our prior analyses, both metrics varied with age (though repetition suppression only marginally (linear age: p = .067; quadratic age: p = .042); Appendix 3 y Tables 22 and 25), suggesting that older participants demonstrated better learning of the structure of the environment. We ran linear regressions examining the relations between each metric, age, and their interaction on neural activation in both the caudate and PFC. We observed no significant effects or interactions of average repetition suppression indices on neural activation (ps > .15; Appendix 3 Tables 23 and 24). We did, however, observe a significant effect of frequency distance on PFC activation (β = .42, SE = .12, p = .0012), such that participants who believed that average frequencies of the high- and low-frequency items were further apart also demonstrated greater PFC activation during encoding of pairs with high- vs. low-frequency items. Here, we did not observe a significant effect of age on PFC activation (β = -.03, SE = .13, p = .82), suggesting that age-related variance in PFC activation may be related to age differences in explicit frequency beliefs. Importantly, however, even when we accounted for both PFC activation and frequency distances, we continued to observe an effect of age on memory difference scores (β = .56, SE = .20, p = .006), which, together with our prior analyses, suggest that developmental differences in value-guided memory are not driven solely by age differences in beliefs about the structure of the environment but also depend on the use of those beliefs to guide encoding.”

We have added the full model results to Appendix 3: Full Model Specification and Results.

Given these results, we have now revised our interpretation of our neural data. Our memory analyses demonstrate that across our age range, we observed age-related differences in both the acquisition of knowledge of the structure of the environment and in its use. Originally, we interpreted the PFC activation as reflecting the use of learned value to guide memory. However, the strong relation we found between frequency distance and PFC activation suggests that the age differences in PFC activation that we observed may also be related to age differences in knowledge of the structure of the environment that governs when control processes should be engaged most strongly. However, these results must be interpreted cautiously. Participants provided explicit frequency reports after they completed the encoding and retrieval tasks, and so explicit frequency reports may have been influenced not only by participants’ memories of online frequency learning, but also by the strength with which they encoded the item and its paired associate, and the experience of successfully retrieving it.

We have now revised our discussion to consider these results. On p. 23, we now write,

“Our neural results further suggest that developmental differences in memory were driven by both knowledge of the structure of the environment and use of that knowledge to guide encoding.”

On p. 24, we write,

“The development of adaptive memory requires not only the implementation of encoding and retrieval strategies, but also the flexibility to up- or down-regulate the engagement of control in response to momentary fluctuations in information value (Castel et al., 2007, 2013; Hennessee et al., 2017). Importantly, value-based modulation of lateral PFC engagement during encoding mediated the relation between age and memory selectivity, suggesting that developmental change in both the representation of learned value and value-guided cognitive control may underpin the emergence of adaptive memory prioritization. Prior work examining other neurocognitive processes, including response inhibition (Insel et al., 2017) and selective attention (Störmer et al., 2014), has similarly found that increases in the flexible upregulation of control in response to value cues enhance goal-directed behavior across development (Davidow et al., 2018), and may depend on the engagement of both striatal and prefrontal circuitry (Hallquist et al., 2018; Insel et al., 2017). Here, we extend these past findings to the domain of memory, demonstrating that value signals derived from the structure of the environment increasingly elicit prefrontal cortex engagement and strengthen goal-directed encoding across childhood and into adolescence.”

And on p. 25, we have added an additional paragraph:

“Further, we also demonstrate that in the absence of explicit value cues, the engagement of prefrontal control processes may reflect beliefs about information value that are learned through experience. Here, we found that differential PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value information reflected individual and age-related differences in beliefs about the structure of the environment; participants who represented the average frequencies of the low- and high-frequency items as further apart also demonstrated greater value-based modulation of lateral PFC activation. It is important to note, however, that we collected explicit frequency reports after associative encoding and retrieval. Thus the relation between PFC activation and explicit frequency reports may be bidirectional — while participants may have increased the recruitment of cognitive control processes to better encode information they believed was more valuable, the engagement of more elaborative or deeper encoding strategies that led to stronger memory traces may have also increased participants’ subjective sense of an item’s frequency (Jonides & Naveh-Benjamin, 1987).”

Third, more discussion is warranted on the nature of age-related changes given that some findings followed quadratic functions and others showed linear. Further interpretation of the quadratic versus linear fits would provide greater insight into the relative rates of maturation across discrete neurobehavioral processes.

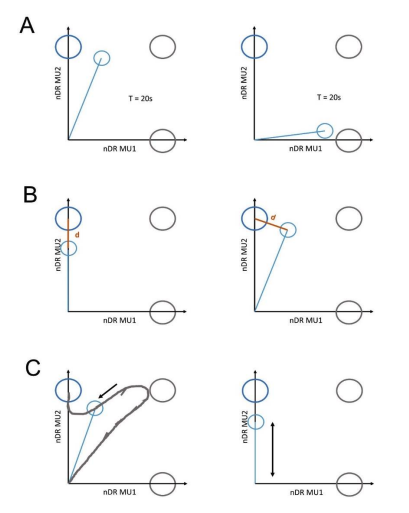

We agree with the reviewer that more discussion is warranted here. While many cognitive processes tend to improve with increasing age, the significant interaction between quadratic age and frequency condition on memory accuracy could reflect a number of different patterns of developmental variance. Because quadratic curves are U-shaped, the significant interaction between quadratic age and frequency condition could reflect a peak in value-guided memory in adolescence. However, the combination of linear and quadratic effects can also capture “plateauing” effects, where the influence of age on a particular cognitive process decreases at a particular developmental timepoint. To determine how to interpret the quadratic effect of age on value-guided memory — and specifically, to test for the presence of an adolescent peak — we ran an additional analysis.

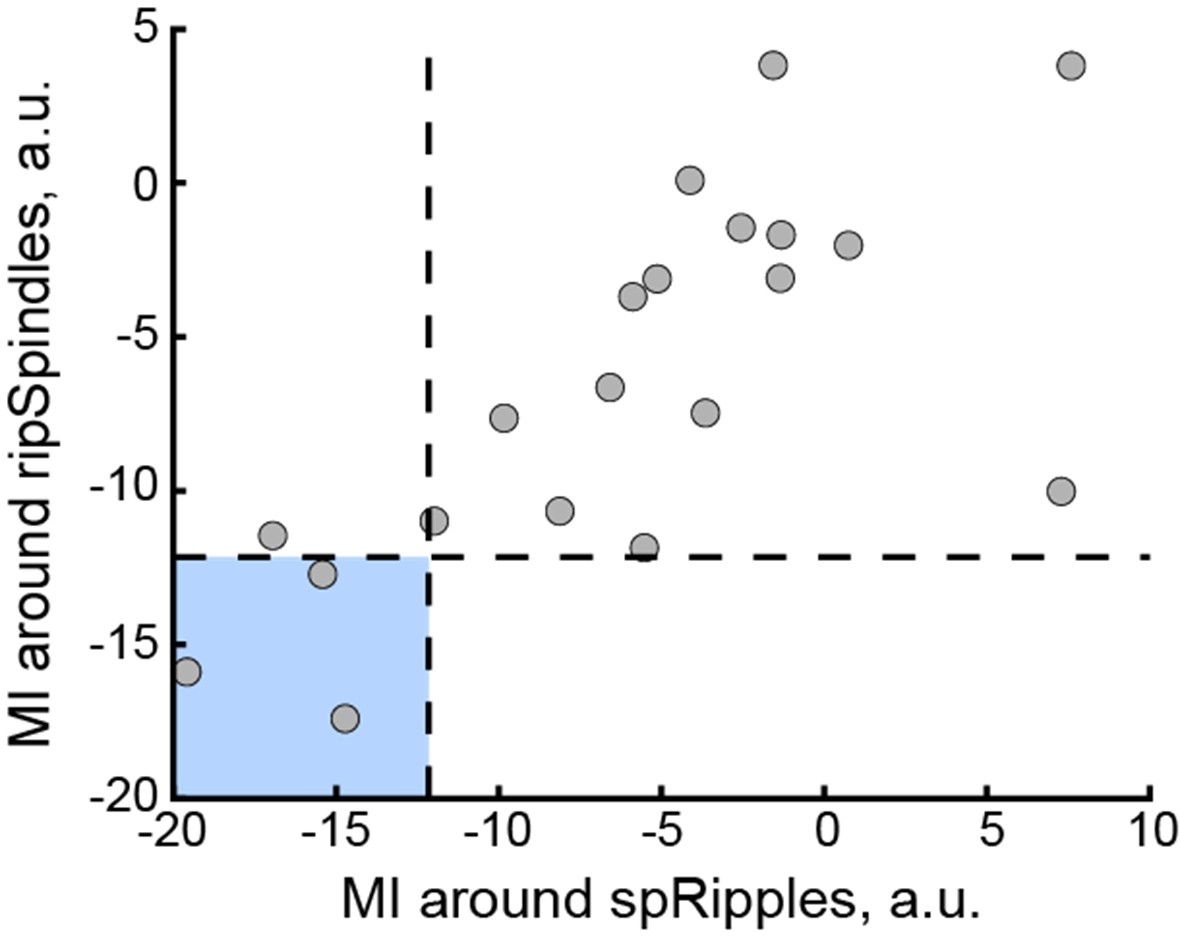

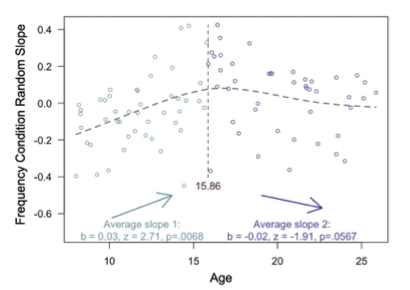

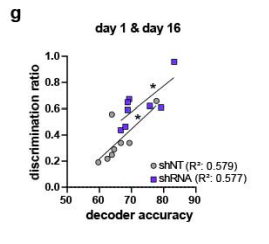

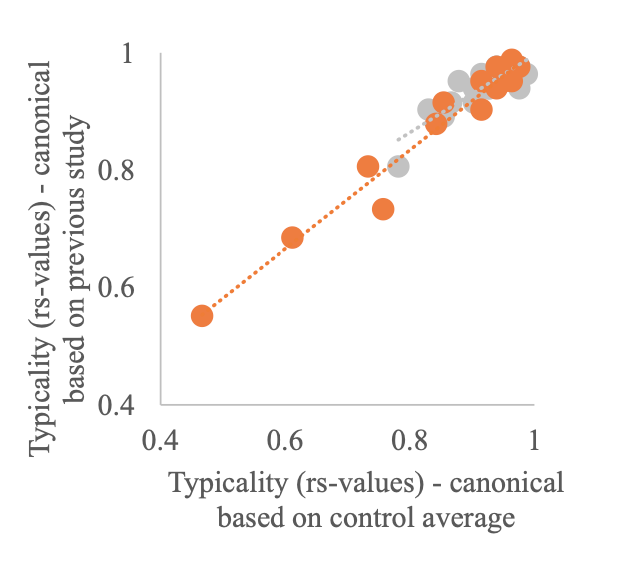

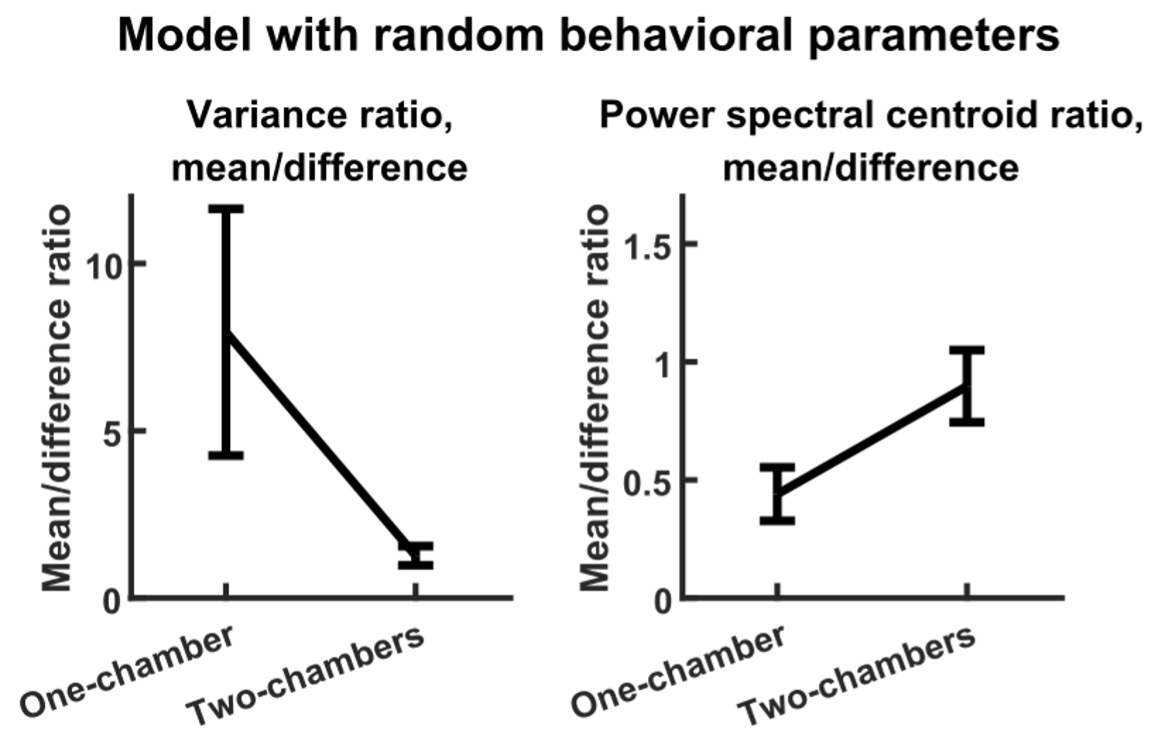

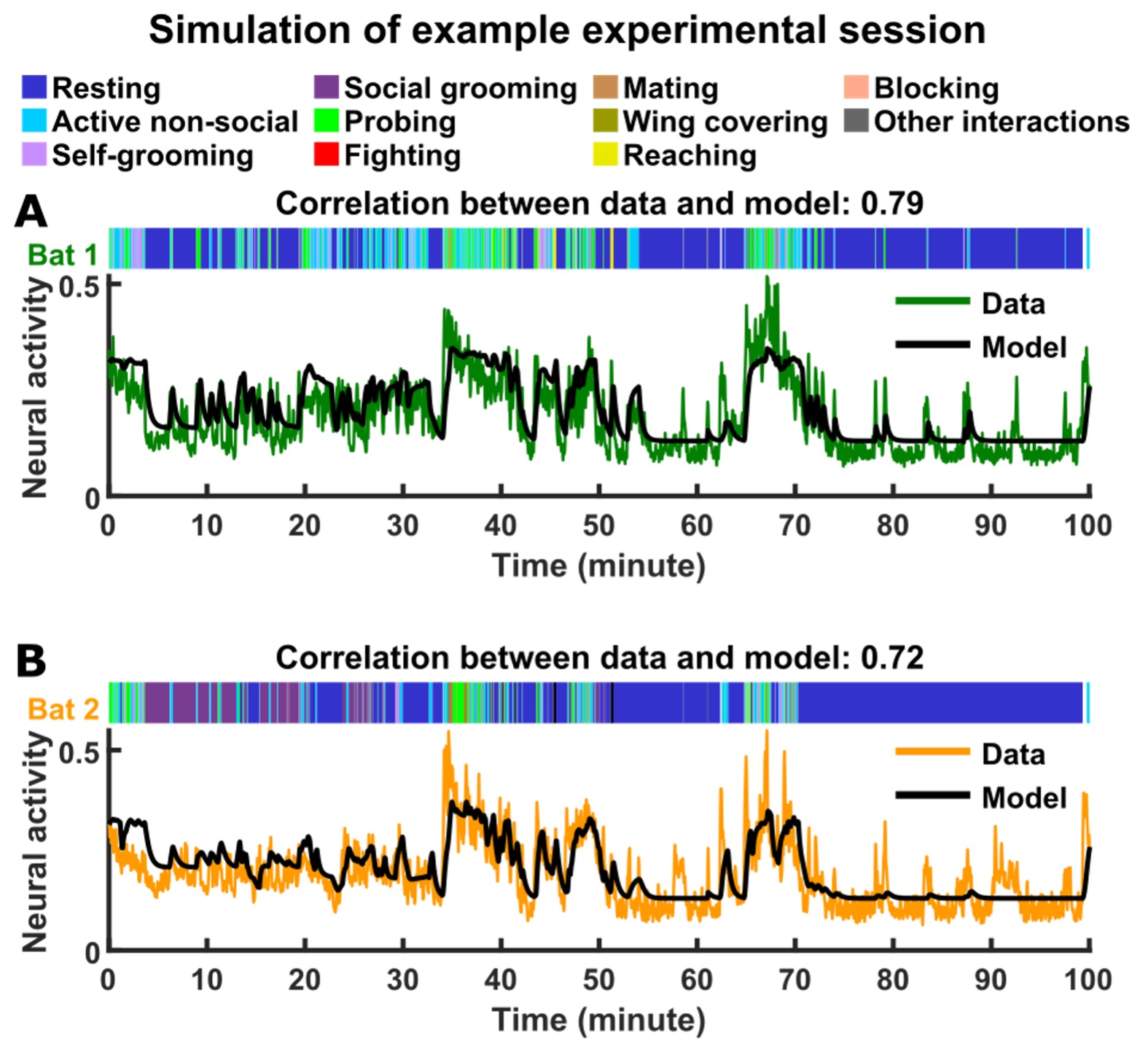

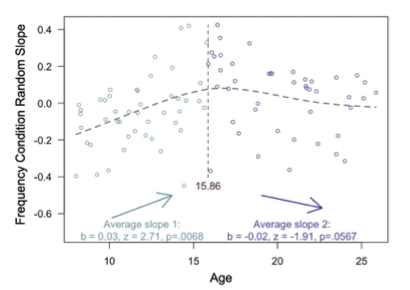

To test for an adolescent peak in value-guided memory, we first fit our memory accuracy model without any age terms, and then extracted the random slope across frequency conditions for each subject. We then conducted a ‘two lines test’ (Simonsohn, 2018) to examine the relation between age and these random slopes. In brief, the two-lines test fits the data with two linear models — one with a positive slope and one with a negative slope, algorithmically determining the breakpoint in the estimates where the signs of the slopes change. When we analyzed our memory data in this way, we found a robust, positive relation between age and value-guided memory (see newly added Appendix 2 Figure 3, also below) from childhood to mid- adolescence, that peaked around age 16 (age 15.86). From age ~16 to early adulthood, however, we observed only a marginal negative relation between age and value-guided memory (p = .0567). Thus, our findings do not offer strong evidence in support of an adolescent peak in value-guided memory — instead, they suggest that improvements in value-guided memory are strongest from childhood to adolescence.

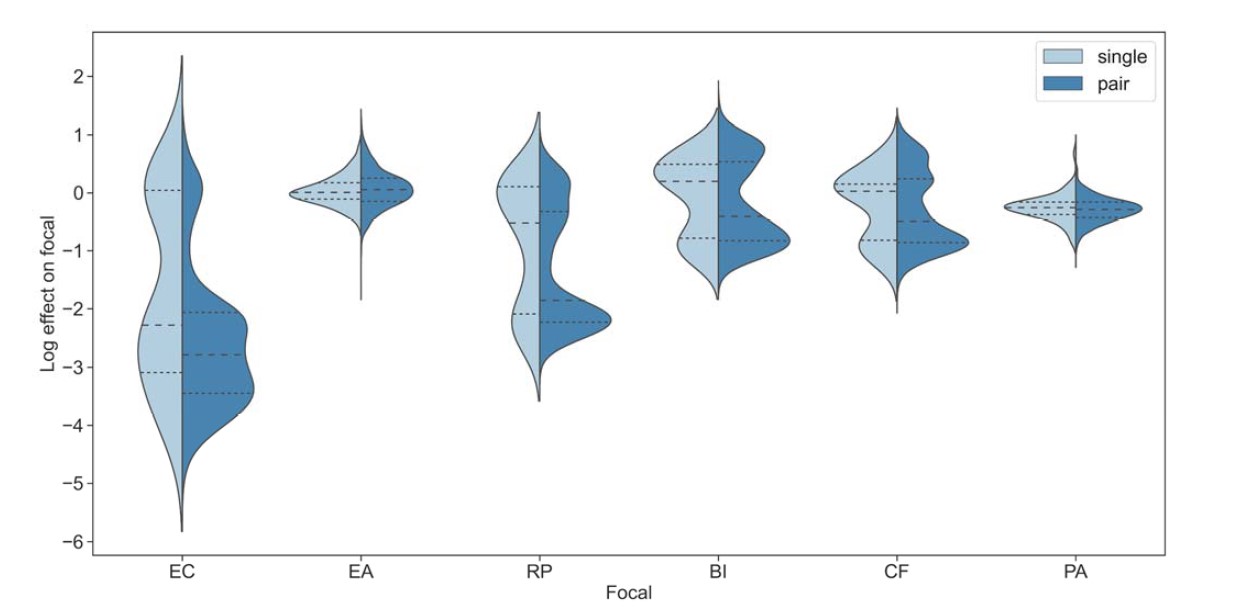

Appendix 2 - Figure 3. Results from the two-lines test (Simonsohn, 2018) revealed that the influence of frequency condition on memory accuracy increased throughout childhood and early adolescence, and did not significantly decrease from adolescence into early adulthood.

To more clearly demonstrate the relation between age and value-guided memory, we have now included the results of the two-lines test in the results section of our main text. On p. 12 - 13, we write:

“In line with our hypothesis, we observed a main effect of frequency condition on memory, χ2(1) = 21.51, p <.001, indicating that individuals used naturalistic value signals to prioritize memory for high-value information. Critically, this effect interacted with both linear age (χ2(1) = 11.03, p < .001) and quadratic age (χ2(1) = 9.51, p = .002), such that the influence of frequency condition on memory increased to the greatest extent throughout childhood and early adolescence.

To determine whether the interaction between quadratic age and frequency condition on memory accuracy reflected an adolescent peak in value-guided memory prioritization, we re-ran our memory accuracy model without including any age terms, and extracted each participant’s random slope across frequency conditions. We then submitted these random slopes to the “two-lines” test (Simonsohn, 2018), which fits two regression lines with oppositely signed slopes to the data, algorithmically determining where the sign flip should occur. The results of this analysis revealed that the influence of frequency condition on memory significantly increased from age 8 to age 15.86 (b = .03, z = 2.71, p = .0068; Appendix 2 – Figure 3), but only marginally decreased from age 15.86 to age 25 (b = -.02, z = 1.91, p = .0576). Thus, the interaction between frequency condition and quadratic age on memory performance suggests that the biggest age differences in value-guided memory occurred through childhood and early adolescence, with older adolescents and adults performing similarly.”

That said, this developmental trajectory is likely specific to the particular demands of our task. In our previous behavioral study that used a very similar paradigm (Nussenbaum, Prentis, & Hartley, 2018), we observed only a linear relation between age and value-guided memory.

Although the task used in our behavioral study was largely similar to the task we employed here, there were subtle differences in the design that may have extended the age range through which we observed improvements in memory prioritization. In particular, in our previous behavioral study, the memory test required participants to select the correct associate from a grid of 20 options (i.e., 1 correct and 19 incorrect options), whereas here, participants had to select the correct associate from a grid of 4 options (1 correct and 3 incorrect options). In our prior work, the need to differentiate the ‘correct’ option from many more foils may have increased the demands on either (or both) memory encoding or memory retrieval, requiring participants to encode and retrieve more specific representations that would be less confusable with other memory representations. By decreasing the task demands in the present study, we may have shifted the developmental curve we observed toward earlier developmental timepoints.

We originally did not emphasize our quadratic findings in the discussion of our manuscript because, given the marginal decrease in memory selectivity we observed from age 16 to age 25 and the different age-related findings across our two studies, we did not want to make strong claims about the specific shape of developmental change. However, we agree with the reviewer that these points are worthy of discussion within the manuscript. We have now amended our discussion on p. 25 accordingly:

“We found that memory prioritization varied with quadratic age, and our follow-up tests probing the quadratic age effect did not reveal evidence for significant age-related change in memory prioritization between late adolescence and early adulthood. However, in our prior behavioral work using a very similar paradigm (Nussenbaum et al., 2020), we found that memory prioritization varied with linear age only. In line with theoretical proposals (Davidow et al., 2018), subtle differences in the control demands between the two tasks (e.g., reducing the number of ‘foils’ presented on each trial of the memory test here relative to our prior study), may have shifted the age range across which we observed differences in behavior, with the more demanding variant of our task showing more linear age-related improvements into early adulthood. In addition, the specific control demands of our task may have also influenced the age at which value- guided memory emerged. Future studies should test whether younger children can modulate encoding based on the value of information if the mnemonic demands of the task are simpler.”

We thank the reviewer for this helpful suggestion, and believe our additions that expand on the quadratic age effects help clarify our developmental findings.

Although hippocamapal and PHC results did not show a main effect of value, it seems by the introduction that this region would be critical for the processes under study. I would suggest including these regions as ROIs of interest guiding age-related differences during the memory encoding and retrieval phases. Even reporting negative findings for these regions would be helpful to readers, especially given the speculation of the negative findings in the discussion.

Thank you for this suggestion. We have now examined how differential neural activation within the hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex during encoding of high- vs. low-value information varies with age. To do so, we followed the same approach as with our PFC and caudate ROI analyses. Specifically, we first identified the voxel within both the hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex with the highest z-statistic from our group-level 5 > 1 encoding contrast. We then drew a 5-mm sphere around these voxels and examined how mean beta weights within these spheres varied with age.

We did not observe any relation between differential hippocampal or parahippocampal cortex activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value information and age (ps > .50). We agree with the reviewer that these results are informative, and have now added them to Appendix 2: Supplementary Analyses, which we refer to in the main text (p. 15). In Appendix 2, we write:

“Hippocampal and parahippocampal cortex activation during encoding A priori, we expected that regions in the medial temporal lobe that have been linked to successful memory formation, including the hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex (Davachi, 2006), may be differentially engaged during encoding of high- vs. low- value information. Further, we hypothesized that the differential engagement of these regions across age may contribute to age differences in value-guided memory. Though we did not see any significant clusters of activation in the hippocampus or parahippocampal cortex in our group level high value vs. low value encoding contrast, we conducted additional ROI analyses to test these hypotheses. As with our other ROI analyses, we first identified the peak voxel (based on its z-statistic; hippocampus: x = 24, y = 34, z = 23; parahippocampal cortex: x = 22, y = 41, z = 16) in each region from our group-level contrast, and then drew 5-mm spheres around them. We then examined how average parameter estimates within these spheres related to both age and memory difference scores.

First, we ran a linear regression modeling the effects of age, WASI scores, and their interaction on hippocampal activation. We did not observe a main effect of age on hippocampal activation, (β = .00, SE = .10, p > .99). We did, however, observe a significant age x WASI score interaction effect (β = .30, SE = .10, p = .003). Next, we conducted another linear regression to examine the effects of hippocampal activation, age, WASI scores, and their interaction on memory difference scores. In contrast to our prefrontal cortex activation results, activation in the hippocampus did not relate to memory difference scores, (β = -.02, SE = .03, p = .50).

We repeated these analyses with our parahippocampal cortex sphere. Here, we did not observe any significant effects of age on parahippocampal activation (β = -.07, SE = .11, p = .50), nor did we observe any effects of parahippocampal activation on memory difference scores (β = .01, SE = .03, p = .25).”

Reviewer #3:

This paper investigated age differences in the neurocognitive mechanisms of value-based memory encoding and retrieval across children, adolescents and young adults. It used a novel experimental paradigm in combination with fMRI to disentangle age differences in determining the value of information based on its frequency from the usage of these learned value signals to guide memory encoding. During value learning, younger participants demonstrated a stronger effect of item repetition on response accuracy, whereas repetition suppression effects in a parahippocampal ROI were strongest in adults. Item frequency modulated memory accuracy such that associative memory was better for previously high-frequency value items. Notably, this effect increased with age. Differences in memory accuracy between low- and high-frequency items were associated with left lateral PFC activation which also increased with age. Accordingly, a mediation analyses revealed that PFC activation mediated the relation between age and memory benefit for high- vs. low-frequency items. Finally, both participants' representations of item frequency (which were more likely to deviate in younger children) and repetition suppression in the parahippocampal ROI were associated with higher memory accuracy. Together, these results data add to the still scarce literature examining how information value influences memory processes across development.

Overall, the conclusions of the paper are well supported by the data, but some aspects of the data analysis need to be clarified and extended.

Empirical findings directly comparing cross-sectional and longitudinal effects have demonstrated that cross-sectional analyses of age differences do not readily generalize to longitudinal research (e.g., Raz et al., 2005; Raz & Lindenberger, 2012). Formal analyses have demonstrated that proportion of explained age-related variance in cross-sectional mediation models may stem from various factors, including similar mean age trends, within-time correlations between a mediator and an outcome, or both (Lindenberger et al., 2011; see also Hofer, Flaherty, & Hoffman, 2006; Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Thus, the results of the mediation analysis showing that PFC activation explains age-related variance in memory difference scores, cannot be taken to imply that changes in PFC activation are correlated with changes in value-guided memory. While the general limitations of a cross-sectional study are noted in the Discussion of the manuscript, it would be important to discuss the critical limitations of the mediation analysis. While the main conclusions of the paper do not critically depend on this analysis, it would be important to alert the reader to the limited information value in performing cross-sectional mediation analyses of age variance.

Thank you for raising this critical point. We have expanded our discussion to specifically note the limitations of our mediation analysis and to more strongly emphasize the need for future longitudinal studies to reveal how changes in neural circuitry may support the emergence of motivated memory across development. Specifically, on p. 26, we now write:

“One important caveat is that our study was cross-sectional — it will be important to replicate our findings in a longitudinal sample to more directly measure how developmental changes in cognitive control within an individual contribute to changes in their ability to selectively encode useful information. Our mediation results, in particular, must be interpreted with caution as simulations have demonstrated that in cross-sectional samples, variables can emerge as significant mediators of age-related change due largely to statistical artifact (Hofer, Flaherty, & Hoffman, 2006; Lindenberger et al., 2011). Indeed, our finding that PFC activation mediates the relation between age and value-guided memory does not necessarily imply that within an individual, PFC development leads to improvements in memory selectivity. Longitudinal work in which individuals’ neural activity and memory performance is sampled densely within developmental windows of interest is needed to elucidate the complex relations between age, brain development, and behavior (Hofer, Flaherty, & Hoffman, 2006; Lindenberger et al., 2011).”

It would be helpful to provide more information on how chance memory performance was handled during data analysis, especially as it is more likely to occur in younger participants. Related to this, please connect the points that belong to the same individual in Figure 3 to facilitate evaluation of individual differences in the memory difference scores.

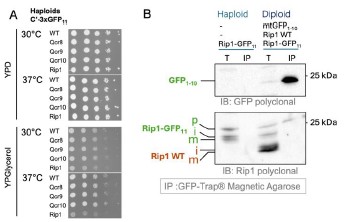

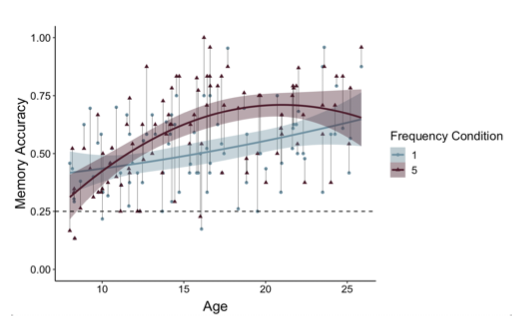

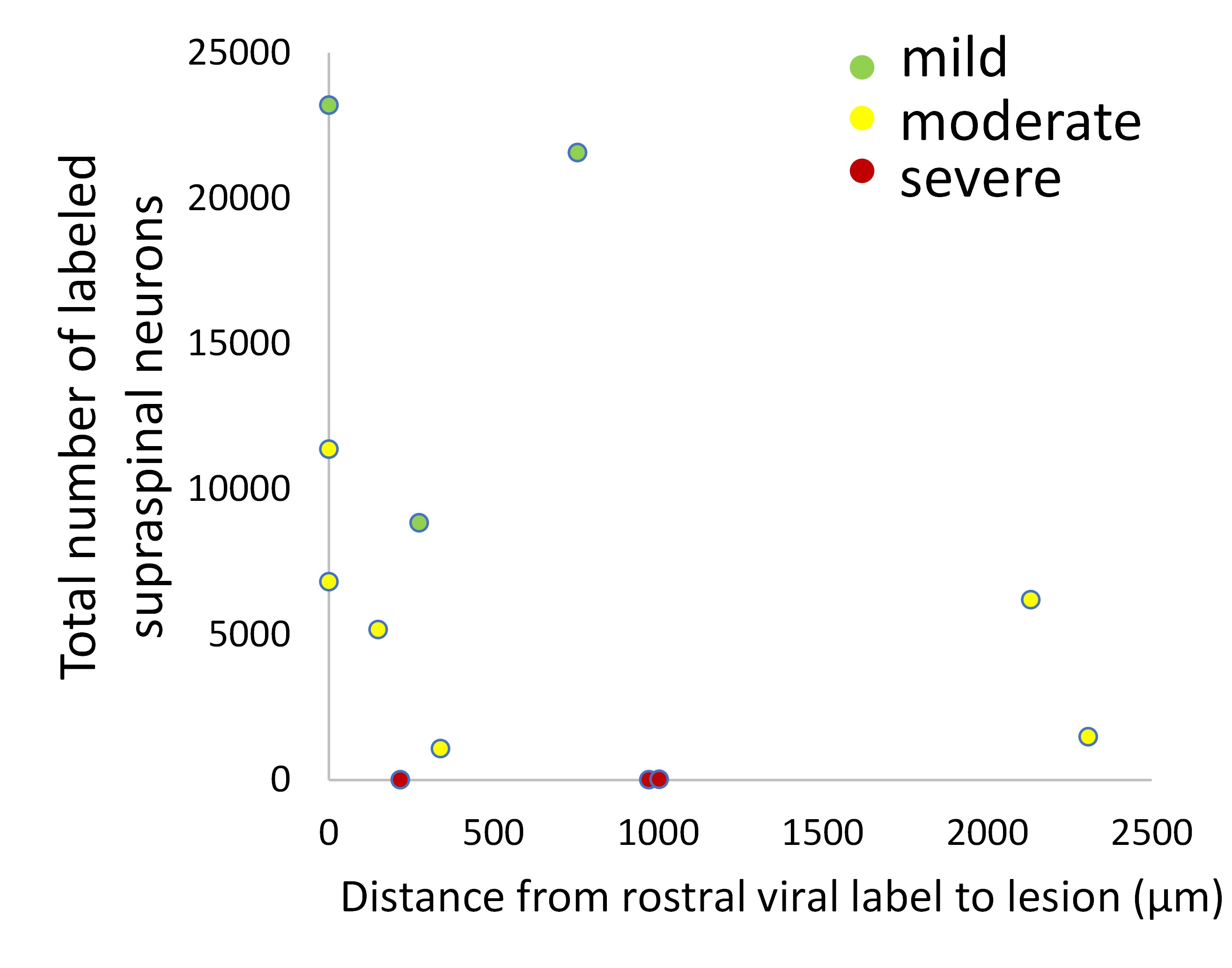

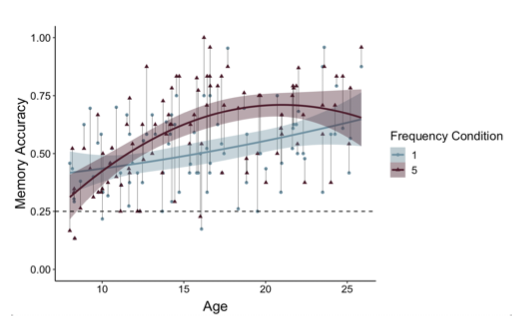

Thank you for raising this important point. On each memory test trial, participants viewed the item (either a postcard or picture) above images of four possible paired associates (see Figure 1 on p. 6). On each memory test trial, participants had 6 seconds to select one of these items. If participants did not make a response within 6 seconds, that trial was considered ‘missed.’ Missed trials were excluded from behavioral analyses and regressed out in neural analyses. If participants selected the correct associate, memory accuracy was coded as ‘1;’ if they selected an incorrect associate, accuracy was coded as ‘0.’ On each trial, there was 1 correct option and 3 incorrect options. As such, chance-level memory performance was 25%. We have now clarified this on p. 34 and included a dashed line indicating chance-level performance within Fig. 4 (formerly Figure 3) on p. 12. In addition, we have also updated Figure 4 (see below) to connect the points belonging to the same participants, as suggested by the reviewer.

Figure 4. Participants demonstrated prioritization of memory for high-value information, as indicated by higher memory accuracy for associations involving items in the five- relative to the one-frequency condition (χ2(1) = 19.73, p <.001). The effects of item frequency on associative memory increased throughout childhood and into adolescence (linear age x frequency condition: χ2(1) = 10.74, p = .001; quadratic age x frequency condition: χ2(1) = 9.27, p = .002).

Out of 90 participants, 2 children performed at or below chance (<= 25% memory accuracy). Interpreting the behavior of the participants who responded to fewer than 12 out of 48 trials correctly is challenging. On the one hand, they might not have remembered anything and responded correctly on these trials due to randomly guessing. On the other hand, they may have implemented an encoding strategy of focusing only on a small number of pairs. Thus, a priori, based on the analysis approach we implemented in our prior, behavioral study (Nussenbaum et al., 2019), we decided to include all participants in our memory analyses, regardless of their overall accuracy. However, when we exclude these two participants from our memory analyses, our main findings still hold. Specifically, we continue to observe main effects of frequency condition and age, and interactions between frequency condition and both linear and quadratic age on associative memory accuracy (ps < .012).

We have now clarified these details about chance-level performance in the methods section of our manuscript on p. 34.

“For our memory analyses, trials were scored as ‘correct’ if the participant selected the correct association from the set of four possible options presented during the memory test, ‘incorrect’ if the participant selected an incorrect association, and ‘missed’ if the participant failed to respond within the 6-second response window. Missed trials were excluded from all analyses. Because participants had to select the correct association from four possible options, chance-level performance was 25%. Two child participants performed at or below chance-level on the memory test. They were included in all analyses reported in the manuscript; however, we report full details of the results of our memory analyses when we exclude these two participants in Appendix 3 (Table 15). Importantly, our main findings remain unchanged.”

In Appendix 3, we include a table with the full results from our memory model without these two participants:

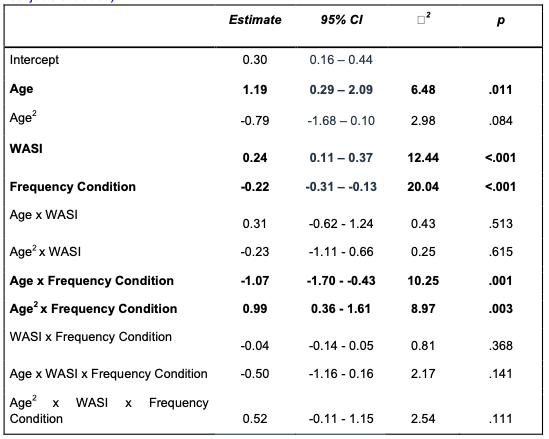

Appendix Table 15: Associative memory accuracy by frequency condition (below chance subjects excluded)

I would like to see some consideration of how the different signatures of value learning, repetition suppression and reported item frequency, are related to the observed PFC and caudate effects during memory encoding. Such a discussion would help the reader connect the findings on learning and using information value across development.

Thank you for this valuable suggestion. We agree that it would be interesting to link frequency- learning behavior to neural activity at encoding. As such, we have now conducted additional analyses to explore these relations.

In the original version of our manuscript, we examined behavior at the item level through mixed- effects models, and neural activation during encoding at the participant level. Thus, to examine the relation between frequency-learning metrics and neural activation at encoding, we created two additional participant-level metrics. For each participant we computed their average repetition suppression index, and a measure of frequency distance. The average repetition suppression index reflects the overall extent to which the participant demonstrated repetition suppression in response to the fifth presentation of the high-frequency items, and is computed by averaging each participant’s repetition suppression indices across items. We hypothesized that participants who demonstrated the greatest degree of repetition suppression might be the most sensitive to the difference between the 1- and 5-frequency items, and therefore, show the greatest differences in striatal and PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value information. The frequency distance metric reflects the average distance between participants’ explicit frequency reports for items that appeared once and items that appeared five times, and is computed by averaging their explicit frequency reports for items in each frequency condition, and then subtracting the average reports in the low-frequency condition from those in the high- frequency condition. We hypothesized that participants with the largest frequency distances might similarly be the most sensitive to the difference between the 1- and 5-frequency items, and therefore, show the greatest differences in striatal and PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value information.

We first wanted to confirm that the relations we observed between repetition suppression, frequency reports, and age, could also be observed at the participant level. In line with our prior, behavioral analyses, we found that age related to both mean repetition suppression indices (marginally; linear age: p = .067; quadratic age: p = .042); and frequency distances (linear and quadratic age: ps < .001).

In addition, we further tested whether these two metrics related to memory performance. In contrast to our item-level findings, we did not observe a significant relation between repetition suppression indices and memory (p = .83). We did observe an effect of frequency distance on memory performance. Specifically, we observed significant interactions between frequency distance and age (p = .014) and frequency distance and quadratic age (p = .021) on memory difference scores, such that the influence of frequency distance on memory difference scores increased with increasing age from childhood to adolescence.

We next examined how mean repetition suppression indices and frequency distances related to differential neural activation during encoding of high- and low-value pairs. In line with our memory findings, we did not observe any significant relations between mean repetition suppression indices and neural activation in the caudate or prefrontal cortex during encoding (ps > .15).

Frequency distance did not relate to caudate activation during encoding nor did we observe a frequency distance x age interaction effect (ps > .16). Frequency distance did, however, relate to differential PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value pairs. Specifically, we observed a main effect of frequency distance on PFC activation (p = .0012), such that participants whose explicit reports of item frequency, were on average, more distinct across frequency conditions, demonstrated increased PFC activation during encoding of pairs involving high- vs. low-frequency items. Interestingly, when we included frequency distance in our model, we no longer observed a significant effect of age on differential PFC activation, nor did we observe a significant frequency distance x age interaction (ps > .13). These findings suggest that PFC activation during encoding may have, in part, reflected participants’ beliefs about the structure of the environment, with participants demonstrating stronger differential engagement of control processes across conditions when their representations of the conditions themselves were more distinct.

Finally, we examined how age, frequency distance, and PFC activation related to memory difference scores. Here, even when controlling for both frequency distance and PFC activation, we continued to observe main effects of age and quadratic age on memory difference scores (linear age: p = .006; quadratic age: p = .001). In line with our analysis of the relation between frequency reports and memory, these results suggest that age-related variance in value-guided memory may depend on both knowledge of the structure of the environment and use of that knowledge to effectively control encoding.

We have now added these results to our manuscript on p. 13 - 14. We write:

“Given the relations we observed between memory and both repetition suppression and frequency reports, we examined whether they related to neural activation in both our caudate and PFC ROI during encoding. To do so, we computed each participant’s average repetition suppression index, and their “frequency distance” — or the average difference in their explicit reports for items in the high- and low-frequency conditions. We expected that participants with greater average repetition suppression indices and greater frequency distances represented the high- and low-frequency items as more distinct from one another and therefore would show greater differences in neural activation at encoding across frequency conditions. In line with our prior analyses, both metrics varied with age (though repetition suppression only marginally (linear age: p = .067; quadratic age: p = .042); Appendix 3 Tables 22 and 25), suggesting that older participants demonstrated better learning of the structure of the environment. We ran linear regressions examining the relations between each metric, age, and their interaction on neural activation in both the caudate and PFC. We observed no significant effects or interactions of average repetition suppression indices on neural activation (ps > .15; Appendix 3 Tables 23 and 24). We did, however, observe a significant effect of frequency distance on PFC activation (β = .42, SE = .12, p = .0012), such that participants who believed that average frequencies of the high- and low-frequency items were further apart also demonstrated greater PFC activation during encoding of pairs with high- vs. low-frequency items. Here, we did not observe a significant effect of age on PFC activation (β = -.03, SE = .13, p = .82), suggesting that age-related variance in PFC activation may be related to age differences in explicit frequency beliefs. Importantly, however, even when we accounted for both PFC activation and frequency distances, we continued to observe an effect of age on memory difference scores (β = .56, SE = .20, p = .006), which, together with our prior analyses, suggest that developmental differences in value-guided memory are not driven solely by age differences in beliefs about the structure of the environment but also depend on the use of those beliefs to guide encoding.”

We have added the full model results to Appendix 3.

Given these results, we have now revised our interpretation of our neural data. Our memory analyses demonstrate that across our age range, we observed age-related differences in both the acquisition of knowledge of the structure of the environment and in its use. Originally, we interpreted the PFC activation as reflecting the use of learned value to guide memory. However, the strong relation we found between frequency distance and PFC activation suggests that the age differences in PFC activation that we observed may also be related to age differences in knowledge of the structure of the environment that governs when control processes should be engaged most strongly. However, these results must be interpreted cautiously. Participants provided explicit frequency reports after they completed the encoding and retrieval tasks, and so explicit frequency reports may have been influenced not only by participants’ memories of online frequency learning, but also by the strength with which they encoded the item and its paired associate, and the experience of successfully retrieving it.

We have now revised our discussion to consider these results. On p. 23, we now write,

“Our neural results further suggest that developmental differences in memory were driven by both knowledge of the structure of the environment and use of that knowledge to guide encoding.”

n p. 24, we write,

“The development of adaptive memory requires not only the implementation of encoding and retrieval strategies, but also the flexibility to up- or down-regulate the engagement of control in response to momentary fluctuations in information value (Castel et al., 2007, 2013; Hennessee et al., 2017). Importantly, value-based modulation of lateral PFC engagement during encoding mediated the relation between age and memory selectivity, suggesting that developmental change in both the representation of learned value and value-guided cognitive control may underpin the emergence of adaptive memory prioritization. Prior work examining other neurocognitive processes, including response inhibition (Insel et al., 2017) and selective attention (Störmer et al., 2014), has similarly found that increases in the flexible upregulation of control in response to value cues enhance goal-directed behavior across development (Davidow et al., 2018), and may depend on the engagement of both striatal and prefrontal circuitry (Hallquist et al., 2018; Insel et al., 2017). Here, we extend these past findings to the domain of memory, demonstrating that value signals derived from the structure of the environment increasingly elicit prefrontal cortex engagement and strengthen goal-directed encoding across childhood and into adolescence.”

And on p. 25, we have added an additional paragraph:

“Further, we also demonstrate that in the absence of explicit value cues, the engagement of prefrontal control processes may reflect beliefs about information value that are learned through experience. Here, we found that differential PFC activation during encoding of high- vs. low-value information reflected individual and age-related differences in beliefs about the structure of the environment; participants who represented the average frequencies of the low- and high-frequency items as further apart also demonstrated greater value-based modulation of lateral PFC activation. It is important to note, however, that we collected explicit frequency reports after associative encoding and retrieval. Thus the relation between PFC activation and explicit frequency reports may be bidirectional — while participants may have increased the recruitment of cognitive control processes to better encode information they believed was more valuable, the engagement of more elaborative or deeper encoding strategies that led to stronger memory traces may have also increased participants’ subjective sense of an item’s frequency (Jonides & Naveh-Benjamin, 1987).”

A point worthy of discussion are the implications of the finding that younger participants demonstrated greater deviations in their frequency reports for the development of value learning, given that frequency reports were found to predict associative memory accuracy.

Thank you for raising this important point. Indeed, one of our main findings is that older participants are better both at learning the structure of their environments and also at using structured knowledge to strategically prioritize memory. In our original manuscript, we described results of a model that included participants’ explicit frequency reports as a predictor of memory. Model comparison revealed that participants’ frequency reports — which we interpret as reflecting their beliefs about the structure of the environment — predicted memory more strongly than the item’s true frequency. In other words, participants’ beliefs about the structure of the environment (even if incorrect) more strongly influenced their memory encoding than the true structure of the environment. Critically, however, frequency reports interacted with age to predict memory (Fig 8). Even when we accounted for age-related differences in knowledge of the structure of the environment, older participants demonstrated a stronger influence of frequency on memory, suggesting they were better able to use their beliefs to control subsequent associative encoding. We have now clarified our interpretation of this model in our discussion on p. 23:

“Importantly, though we observed age-related differences in participants’ learning of the structure of their environment, the strengthening of the relation between frequency reports and associative memory with increasing age suggests that age differences in learning cannot fully account for age differences in value-guided memory. Even when accounting for individual differences in participants’ explicit knowledge of the structure of the environment, older participants demonstrated a stronger relation between their beliefs about item frequency and associative memory, suggesting that they used their beliefs to guide memory to a greater degree than younger participants.”

As noted by the reviewer, however, our initial memory analysis did not account for age-related differences in participants’ initial, online learning of item frequency, and our neural analyses further did not account for age differences in explicit frequency reports. We have now run additional control analyses to account for the potential influence of individual differences in frequency learning on associative memory. Specifically, for each participant, we computed three metrics: 1.) their overall accuracy during frequency-learning, 2.) their overall accuracy for the last presentation of each item during frequency-learning (as suggested by Reviewer 2), and 3.) the mean magnitude of the error in their frequency reports. We then included these metrics as covariates in our memory analyses.

When we include these control variables in our model, we continue to observe a robust effect of frequency condition (p < .001) as well as robust interactions between frequency condition and linear and quadratic age (ps < .003) on associative memory accuracy. We also observed a main effect of frequency error magnitude on memory accuracy (p < .001). Here, however, we no longer observe main effects of age or quadratic age on overall memory accuracy. Given the relation we observed between frequency error magnitudes and age, the results from this model suggests that there may be age-related improvements in overall memory that influence both memory for associations as well as learning of and memory for item frequencies. The fact that age no longer relates to overall memory when controlling for frequency error magnitudes suggest that age-related variance in memory for item frequencies and memory for associations are strongly related within individuals. Importantly, however, age-related variance in memory for item frequencies did not explain age-related variance in the influence of frequency condition on associative memory, suggesting that there are developmental differences in the use of knowledge of environmental structure to prioritize valuable information in memory that persist even when controlling for age-related differences in initial learning of environmental regularities. Given the importance of this analysis in elucidating the relation between the learning of environmental structure and value-guided memory, we have now updated the results in the main text of our manuscript to include them. Specifically, on p. 13, we now write:

“Because we observed age-related differences in participants’ online learning of item frequencies and in their explicit frequency reports, we further examined whether these age differences in initial learning could account for the age differences we observed in associative memory. To do so, we ran an additional model in which we included each participant’s mean frequency learning accuracy, mean frequency learning accuracy on the last repetition of each item, and explicit report error magnitude as covariates. Here, explicit report error magnitude predicted overall memory performance, χ2(1) =13.05, p < .001, and we did not observe main effects of age or quadratic age on memory performance (ps > .20). However, we continued to observe a main effect of frequency condition, χ2(1) = 19.65 p < .001, as well as significant interactions between frequency condition and both linear age χ2(1) = 10.59, p = .001, and quadratic age χ2(1) = 9.15, p = .002. Thus, while age differences in initial learning related to overall memory performance, they did not account for age differences in the use of environmental regularities to strategically prioritize memory for valuable information.”

In addition, as suggested by the reviewer, we also included the three covariates as control variables in our mediation analysis. When controlling for online frequency learning and explicit frequency report errors, PFC activity continued to mediate the relation between age and memory difference scores. We have now included these results on p. 16 - 17 of the main text:

“Further, when we included quadratic age, WASI scores, online frequency learning accuracy, online frequency learning accuracy on the final repetition of each item, and mean explicit frequency report error magnitudes as control variables in the mediation analysis, PFC activation continued to mediate the relation between linear age and memory difference scores (standardized indirect effect: .56, 95% confidence interval: [.06, 1.35], p = .023; standardized direct effect; 1.75, 95% confidence interval: [.12, .3.38], p = .034).”

We also refer to these analyses when we interpret our findings in our discussion. On p. 23, we write:

“In addition, we continued to observe a robust interaction between age and frequency condition on associative memory, even when controlling for age-related change in the accuracy of both online frequency learning and explicit frequency reports. Thus, though we observed age differences in the learning of environmental regularities and in their influence on subsequent associative memory encoding, our developmental memory effects cannot be fully explained by differences in initial learning.”

We thank the reviewer for this constructive suggestion, as we believe these control analyses strengthen our interpretation of age differences in both the learning and use of environmental regularities to prioritize memory.