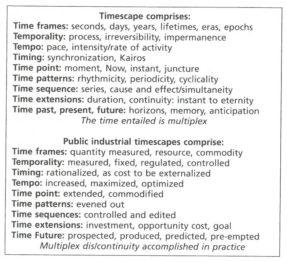

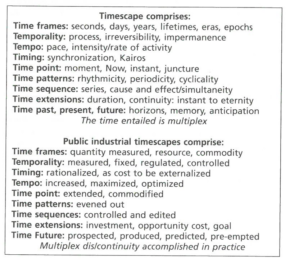

I propose that we think a bout temporal relations with reference to a cluster of temporal features, each implicated in all the others but not necessarily of equal importance in each instance. We might call this cluster a timescape. The notion of 'scape' is important here as it indicates, first, that time is inseparable from space and matter, and second, that context matters.

Definition of timescape -- "a cluster of temporal features, each implicated in all the others but not necessarily of equal importance in each instance."