the head of OpenAI, debuted his Sora app, which creates alarmingly realistic videos of fake scenes.

This leads to political division, mistrust, confusion, and harm to the individuals who have fake content being made about them.

the head of OpenAI, debuted his Sora app, which creates alarmingly realistic videos of fake scenes.

This leads to political division, mistrust, confusion, and harm to the individuals who have fake content being made about them.

‘the future is real in so far as social actors produce representations of the future which have an effect on others’ actions in the present’ (Tutton, 2017, p. 483)

for - quote - the future - the future is real in so far as social actors produce representations of the future which have an effect on others’ actions in the present - Tutton, 2017, p. 483

If you’re just sitting in a cave for nine years, desire intelligently doesn’t seem to come into play very much. But if you’re in the world with other people and you’re living a life, how do you desire, how do you connect, how do you attach without greed, without trying to control other people in order to not lose them or lose their love? We have to learn to attach, to desire intelligently, to hold lightly.

for - desire intelligently - without greed - without trying to control - in the real world - not in a cave - Zen - Barry Magid

Across all global land area, models underestimate positive trends exceeding 0.5 °C per decade in widening of the upper tail of extreme surface temperature distributions by a factor of four compared to reanalysis data and exhibit a lower fraction of significantly increasing trends overall.

for - question - climate crisis - climate models underestimate warming in some areas up to 4x - what is the REAL carbon budget if adjusted to the real situation?

question - climate crisis - climate models underestimate warming in some areas up to 4x<br /> - What is the REAL carbon budget if adjusted to the real situation? - If we have even less than 5 years remaining in our carbon budget, then how many years do we actually have to stay within 1.5 Deg C?

China Sea as the edge of the world and is used to imagine the margins of the world as a realm of marvels and unknown dangers.

Benjamin's travelogue is a product of his imagination, influenced by biblical authority and rumors, rather than actual geographical knowledge.

Jewish utopia in the Arabian Peninsula, where 300,000 Jews live in 40 cities and 200 villages, free from the rule of gentiles.

universal Jewish community that despite its dispersion among various Muslim and Christian regimes still managed to preserve a strong sense of unity and cohesion

big Jewish community is the focus of his travel, he doesnt notice other things, rest is fictious

"a day's journey" to indicate close social interactions among Jewish communities,

rather a way to link places along a real but somewhat abstracted route.

medieval understanding of travel writing.

mprecise unit of "a day's journey" and the parasang, an ancient Persian unit of measurement

geography is experienced through human movement on specific routes.

literary grid that allows the author to reflect on the medieval world from a Jewish perspective.

1:03:51 By getting people used to DEBT being SAVINGS, they can focus on the REAL things that matter

here it comes, in plain view, the onslaught sent by Zeus for my own terror. Oh holy Mother Earth, oh sky whose light revolves for all, you see me. You see the wrongs I suffer. here it comes, in plain view, the onslaught sent by Zeus for my own terror. Oh holy Mother Earth, oh sky whose light revolves fo

having a high blood glucose is a manifestation of the problem not the problem itself because if you 00:02:34 didn't have the mitochondrial dysfunction you wouldn't have the high blood glucose so the high blood glucose is Downstream of the actual problem 00:02:45 and insulin is a way to shall we say cover up the problem

for - key insight - insulin covers up the real problem of mitochondria dysfunction

Essentially it analyzes the process of an illusion crystallizing out of emptiness and being taken for reality.

for - key insight - the real is the illusory - interdependent origination - emptiness

key insight - the real is the illusory - There is profundity in this single statement that takes huge effort to truly understand - because we've been heaped with so much social conditioning - For example, a lot of psychological science research distinguishes between - what is real and - what is an illusion - However, the investigations that these teachings are referring to reveal that what both - conventional science and - the ordinary, mundane view of reality - take for real are both illusory when we deeply understand interdependent origination - The illusion is extraordinarily real and - it is a huge leap to know, feel and experience that ALL of reality, including both your - inner private world and the - outer shared world are illusory - That is, that while appearing, everything that appears is only due to other causes and conditions - Another way to say this is that nouns (things/objects) are temporary designations - underneath them is always verbs (processes)

this is whitehead's fallacy of misplaced concreteness

for - key insight - Whitehead's fallacy of misplaced concreteness - adjacency - fallacy of misplaced concreteness - climate denialism - mistrust in science - polycrisis - Deep Humanity

key insight - Whitehead's fallacy of misplaced concreteness - This helps explain the rising rejection of science from the masses. I didn't realize there was already a name for the phenomena responsible for the emergence of collective denialist behavior

adjacency - between - fallacy of misplaced concreteness - increasing collective rejection of science in the polycrisis - adjacency statement - Whitehead's fallacy of misplaced concreteness exactly names and describes - the growing trend of a populus rejection of climate science (climate denialism), COVID vaccine denialism, exponential growth of conspiracy theory and misinformation - because of the inability for non-elites and elites alike to concretize abstractions the same way that elite scientists and policy-makers do - Research papers have shown that the knowledge deficit model which was relied upon for decades was not accurate representation of climate denialism - Yet, I would hold that Whitehead's fallacy of misplaced concretism plays a role here - This mistrust in science is rooted in this fallacy as well as progress traps - Deep Humanity is quite steeped in Whitehead's process relational ontology and the fallacy of misplaced concreteness requires mass education for a sustainable transition - This abstract concreteness is everywhere: - Shift from Ptolemy's geocentric worldview to the Copernican heliocentric worldview - Now we are told that the sun is not fixed, but is itself rotating around the Milky Way with billions of other galaxies - scientific techniques like radiocarbon dating for dating objects in deep time - climate science - atomic physics - quantum physics - distrust of vaccines, which we cannot see - Timothy Morton's hyperobjects is related to this fallacy of misplaced concreteness. - "Seeing is believing" but we cannot directly experience the ultra large or ultra small. So we have scientific language that draws parallels to that, but it is not a direct experience. - - Those not steeped in years or decades of science have the very real option of feeling that the concepts are fallacies and don't hold as much weight as that which they can experience directly, even though those concepts have obviously produced artefacts that they use, like cellphones, the internet and airplanes.

for - Alfred North Whitehead - philosophy - process

Summary - This is a very insightful presentation of Whitehead's process philosophy. It's the first time I was introduced to it via Gyuri but I can see why he wanted to. I could identify many parallels with SRG and Deep Humanity ideas.

our slave owners want to stay in control, because they are control freaks, real fascists.<br /> i guess "the event" will be a blackout, plus civil war vs migrants, so they can declare martial law

why is, are so many working class whites driving toward the hard right and wanting to support, you know, what seemed to us kind of insane policies? Well, people are desperate. They're looking for the answer. They're looking for the problem, and they're being told the problem is immigrants. And we don't look at wealth as the problem.

// Not recommended: log into the application like a user

// by typing into the form and clicking Submit

// While this works, it is slow and exercises the login form

// and NOT the feature you are trying to test.

6:30

This book was not easy to write. [...] This book tried my patriotism, and it stretched it to thin, to a string. Because as I went through these documents, and looked at the behavior of my country, it was appalling. It was shocking, that we were involved in things that we've been involved in over the last 50 years. In fact, I got chastised for bringing up a word that I find ironic, I guess you're not supposed to use. When you read this, what bothered me, but I'll use it. I tell it like it is. I believe, in many instances in this book, you can substitute the word Nazi and it works. There's behavior in this book that is as you'd expect it from the Nazi's. But it isn't the Nazi's, it's us. It’s our country.

yes, operation paperclip.

the US government recruited literal Nazi scientists for the US military and secret services.

also here in germany, the "denazification" was only for show, to deceive a naive public. obviously, the puppet masters have never changed, and also many of their puppets have continued their work in government and industry.

fun fact: Theodor Pfizer was a nazi collaborateur. yes, the same Pfizer family as the pharma corporation Pfizer.

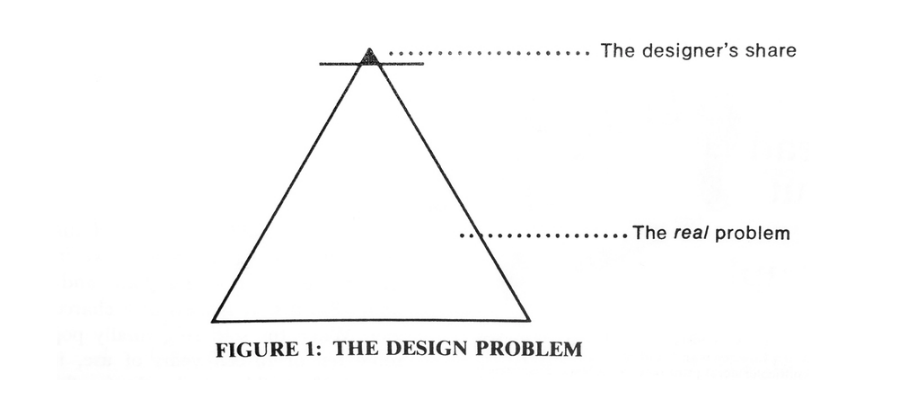

Victor Papanek’s Design Problem, 1975.

Three diagrams will explain the lack of social engagement in design. If (in Figure 1) we equate the triangle with a design problem, we readily see that industry and its designers are concerned only with the tiny top portion, without addressing themselves to real needs.

(Design for the Real World, 2019. Page 57.)

The other two figures merely change the caption for the figure.

In ecology, edge effects are changes in population or community structures that occur at the boundary of two or more habitats.[1] Areas with small habitat fragments exhibit especially pronounced edge effects that may extend throughout the range. As the edge effects increase, the boundary habitat allows for greater biodiversity.

It was in the Design Science Studio that I learned about edge effects.

Yesterday, I was thinking about how my life embodies the concept of edge effects. That same day, a book was delivered to our door, Design for the Real World by Victor Papanek.

Today, I was reading these words:

Integrated, comprehensive, anticipatory design is the act of planning and shaping carried on across the various disciplines, an act continuously carried on at interfaces between them.

Victor Papanek goes on to say:

It is at the border of different techniques or disciplines that most new discoveries are made and most action is inaugurated. It is when two differing areas of knowledge are brought into contact with one another that… a new science may come into being.

(Page 323)

The Bauhaus spread its ideas because it existed at the boundaries, the avant-garde, the edges of what was thought to be possible, especially as a socialist utopian idea found its way to a capitalist industrial-military complex, where the concept of modernism was co-opted and colonized by globalizing economic forces beyond the control of the individual. Design was the virus that propagated around the world through the vehicle of corporate globalization.

That same design ethic is infecting corporations with a conscience, with empathy, with a process that begins with listening to people. Design is the virus that can spread the values of unconditional love throughout the body of neoliberal capitalism.

You have to make up your mind either to make sense or to make money, if you want to be a designer.

— R. Buckminster Fuller

(Page 86)

by Victor Papanek

Many of the “sane design” or “design reform” movements of the time, such as those engendered by the writings and teachings of William Morris in England and Elbert Hubbard in the United States, were rooted in a sort of Luddite antimachine philosophy. By contrast Frank Llloyd Wright said as early as 1894 that “the machine is here to stay” and that the designer should “use this normal tool of civilization to best advantage instead of prostituting it as he has hitherto done in reproducing with murderous ubiquity forms born of other times and other conditions which it can only serve to destroy.” Yet designers of the last century were either perpetrators of voluptuous Victorian-Baroque or members of an artsy-craftsy clique who were dismayed by machine technology. The work of the Kunstgewerbeschule in Austria and the German Werkbund anticipated things to come, but it was not until Walter Gropius founded the German Bauhaus in 1919 that an uneasy marriage between art and machine was achieved.

No design school in history had greater influence in shaping taste and design than the Bauhaus. It was the first school to consider design a vital part of the production process rather than “applied art” or “industrial arts.” It became the first international forum on design because it drew its faculty and students from all over the world, and its influence traveled as these people later founded design offices and schools in many countries. Almost every major design school in the United States today still uses the basic foundation course developed by the Bauhaus. It made good sense in 1919 to let a German 19-year-old experiment with drill press and circular saw, welding torch and lathe, so that he might “experience the interaction between tool and material.” Today the same method is an anachronism, for an American teenager has spent much of his life in a machine-dominated society (and cumulatively probably a great deal of time lying under various automobiles, souping them up). For a student whose American design school slavishly imitates teaching patterns developed by the Bauhaus, computer sciences and electronics and plastics technology and cybernetics and bionics simply do not exist. The courses the Bauhaus developed were excellent for their time and place (telesis), but American schools following this pattern in the eighties are perpetuating design infantilism.

The Bauhaus was in a sense a nonadaptive mutation in design, for the genes contributing to its convergence characteristics were badly chosen. In boldface type, it announced its manifesto: “Architects, sculptors, painters, we must all turn to the crafts.… Let us create a new guild of craftsmen!” The heavy emphasis on interaction between crafts, art, and design turned out to be a blind alley. The inherent nihilism of the pictorial arts of the post-World War I period had little to contribute that would be useful to the average, or even to the discriminating, consumer. The paintings of Kandinsky, Klee, Feininger, et al., on the other hand, had no connection whatsoever with the anemic elegance some designers imposed on products.

(Pages 30-31)

Victor Papanek’s book includes an introduction written by R. Buckminster Fuller, Carbondale, Illinois. (Sadly, the Thames & Hudson 2019 Third Edition does not include this introduction. Monoskop has preserved this text as a PDF file of images. I have transcribed a portion here.)

Victor Papanek

MRIIDS. (n.d.). Retrieved September 6, 2021, from https://mriids.org/about

entropic

This is what Edgar Orrin Klapp meant when he wrote in his 1986 Overload and Boredom: Essays on the Quality of Life in the Information Society that “meaning and interest are found mostly in the mid-range between extremes of redundancy and variety-these extremes being called, respectively, banality and noise” (). Redundancy is repetition of the same, which creates a condition of insufficient difference, while noise is the chaos of non-referentiality, or entropy. In a way, these extremes collapse into each other, in that both can be viewed “as a loss of potential … for a certain line of action at least” ().

There is perhaps something of "the real" here, as well. Volker Woltersdorff (2012, 134) writes that: The law of increasing entropy is a concept of energy in the natural sciences that assumes the tendency of all systems to eventually reach their lowest level of energy. Organic systems therefore tend toward inertia … Freud identifies the death drive with entropy … within his theory, the economy of the death drive is to release tension."

Adam Phillips clarifies the death drive: “People are not, Freud seems to be saying, the saboteurs of their own lives, acting against their own best interests; they are simply dying in their own fashion (to describe someone as self-destructive is to assume a knowledge of what is good for them, an omniscient knowledge of the ‘real’ logic of their lives)” (2000, 81, cf. 77).

The real

In Return of the Real the critic Hal Foster considers "the real" to be art and theory grounded in the materiality of actual bodies and social sites. (As opposed to the "art-as-text" model of the 70s and the "art-as-simulacrum" model of the 80s).

In Rewiring the Real, Mark Taylor describes the thought of "god" and "the real" as synonymous. One vision of theism he is concerned with is that of Schleirmacher, Schiller, Schlegel, Hölderlin, and Novalis, through to Coleridge, Wordsworth, Emerson, Thoreau, and Stevens, where god becomes identified as the creative impulse immanent in the world. He is also concerned with the ontological thought of Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Freud, Poe, Melville, Blanchot, Jabès, and Derrida for whom the real is "wholly other, or, in Kierkegaard's words that continue to echo, 'infinitely and qualitatively different'" (4). In the latter tradition, Lacan, following most closely on Freud, is especially associated with the concept of the real. For him, the real is the state of nature from which we have been severed by our entrance into language. It erupts, however, whenever we are forced to confront the materiality of our existence, as with needs and drives, such as for hunger, sex, and sleep.

The real

In Return of the Real the critic Hal Foster considers "the real" to be art and theory grounded in the materiality of actual bodies and social sites. (As opposed to the "art-as-text" model of the 70s and the "art-as-simulacrum" model of the 80s).

In Rewiring the Real, Mark Taylor describes the thought of "god" and "the real" as synonymous. One vision of theism he is concerned with is that of Schleirmacher, Schiller, Schlegel, Hölderlin, and Novalis, through to Coleridge, Wordsworth, Emerson, Thoreau, and Stevens, where god becomes identified as the creative impulse immanent in the world. He is also concerned with the ontological thought of Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Freud, Poe, Melville, Blanchot, Jabès, and Derrida for whom the real is "wholly other, or, in Kierkegaard's words that continue to echo, 'infinitely and qualitatively different'" (4). In the latter tradition, Lacan, following most closely on Freud, is especially associated with the concept of the real. For him, the real is the state of nature from which we have been severed by our entrance into language. It erupts, however, whenever we are forced to confront the materiality of our existence, as with needs and drives, such as for hunger, sex, and sleep.

entropic

This is what Edgar Orrin Klapp meant when he wrote in his 1986 Overload and Boredom: Essays on the Quality of Life in the Information Society that “meaning and interest are found mostly in the mid-range between extremes of redundancy and variety-these extremes being called, respectively, banality and noise” (). Redundancy is repetition of the same, which creates a condition of insufficient difference, while noise is the chaos of non-referentiality, or entropy. In a way, these extremes collapse into each other, in that both can be viewed “as a loss of potential … for a certain line of action at least” ().

There is perhaps something of "the real" here, as well. Volker Woltersdorff (2012, 134) writes that: The law of increasing entropy is a concept of energy in the natural sciences that assumes the tendency of all systems to eventually reach their lowest level of energy. Organic systems therefore tend toward inertia … Freud identifies the death drive with entropy ... within his theory, the economy of the death drive is to release tension."

Adam Phillips clarifies the death drive: “People are not, Freud seems to be saying, the saboteurs of their own lives, acting against their own best interests; they are simply dying in their own fashion (to describe someone as self-destructive is to assume a knowledge of what is good for them, an omniscient knowledge of the ‘real’ logic of their lives)” (2000, 81, cf. 77).

and developing solutions to real challenges

Lots of mention of engaging in real world issues/solutions/etc. Is this at odds with the mandates of FERPA and privacy/security in general that govern ed-tech integration in education?