Reply to Hajo Bakker on LinkedIn

Hajo Bakker Exam vs. Test -- Een examinering moet veel vanafwegen en niet regulier gebeuren.

Een test (toets) mag vaker gebeuren, en moet weinig vanaf hangen... Geen ouders die straffen voor een laag cijfer (of cijfers afschaffen), geen adviezen die daarvanafhangen, etc.

Het doel van een toets is om je aan te geven wat je krachten en minder sterke punten zijn, dus waar je je op moet focussen met toekomst leren. Dit kan alleen op het moment dat je een toets nabespreekt en op individueel niveau. Klassikaal bespreken heeft vaak weinig nut.

Daarbij komt ook dat een student moet snappen WAAROM het helpt om na te bespreken, de wetenschap erachter. Op het moment dat je de waarom achter het hoe niet goed snapt heeft het hoe minder effect. (dit is waarom in het 4C/ID model ze in een scaffold beginnen met de laatste stap, waarin de informatie van voorgaande stappen is gegeven. Dit zodat als je de vorige stap gaat leren, je een beter idee hebt waar het uiteindelijk voor gebruikt gaat worden en je er dus een betere invulling aan kan geven.)

Semantische verschillen zijn vaak uiterst nuttig om complexe stof te begrijpen. Op het moment dat ze exact hetzelfde waren heeft het weinig nut om meerdere termen te hebben en zouden ze synoniem zijn.

"Exam" is geen synoniem van "test".

Genuanceerde verschillen zijn vaak nuttiger dan "umbrella terms" om goed te communiceren, als uiterst subliem wordt beargumenteerd in "Science of Memory: Concepts" van Roediger III et al.

Daarnaast komt uiteraard bij kijken dat neurocognitieve wetenschap een blauwdruk geeft voor hoe onze brein architectuur in elkaar zit (zie bijvoorbeeld John Sweller, Cognitive Load Theory 2011, en The Forgetting Machine, Rodrigo Quian Quiroga, 2017, Science of Memory: Concepts, Roediger et al., 2007, Ten Steps to Complex Learning, van Merriënboer, 2017).

Dit is universeel toepasbaar, afgezien van mensen met een cognitieve aandoening bijvoorbeeld, dit gaat dus over neurotypische breinen.

Leerstijlen zijn een mythe, wel hebben wij leervoorkeuren, maar door alleen in onze leervoorkeur te leren missen wij bepaalde informatie die cruciaal kan zijn voor beter begrip en meesterschap (mastery).

Beter is het om studietechnieken te gebruiken die overeenkomen met brein-architectuur en die onder te knie te krijgen.

Meer cognitieve belasting te gebruiken (zonder cognitieve overbelasting te veroorzaken). Als leren "makkelijk" voelt is het over het algemeen niet uitdagend genoeg en/of de techniek niet nuttig. Herlezen / samenvatten is simpel maar vrij inefficiënt. Het maken van een GRINDEmap voelt moeilijk maar is vele malen effectiever (zie ook the misinterpreted effort hypothesis).

Zoals Dr. Ahrens al zei: "The one who does the effort, does the learning."

Verder heb ik een heleboel ideëen voor een optimaal onderwijs dat zich aanpast aan het individu in plaats van aan het systeem, maar dit is een te complex en groot onderwerp om zo even hier neer te zetten.

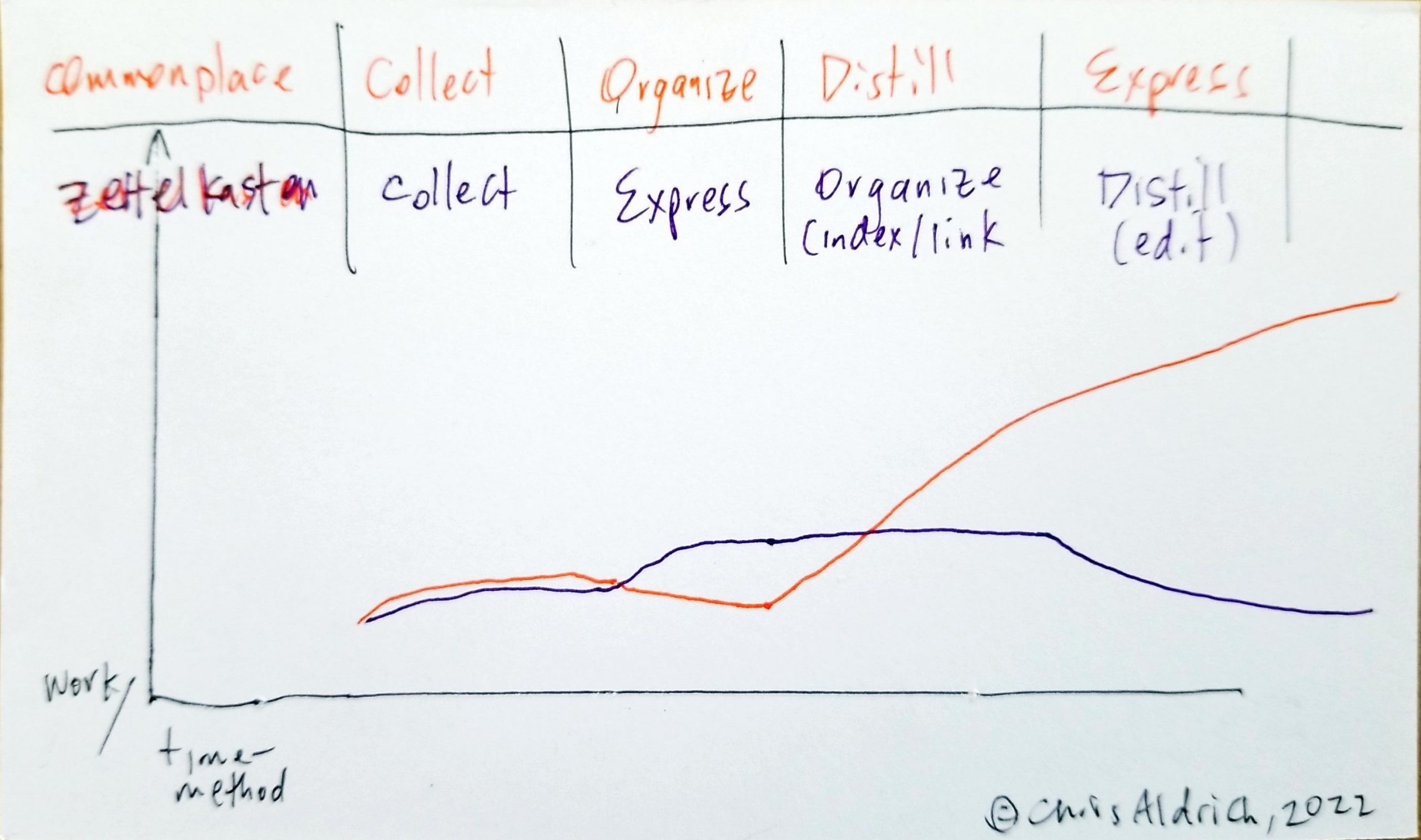

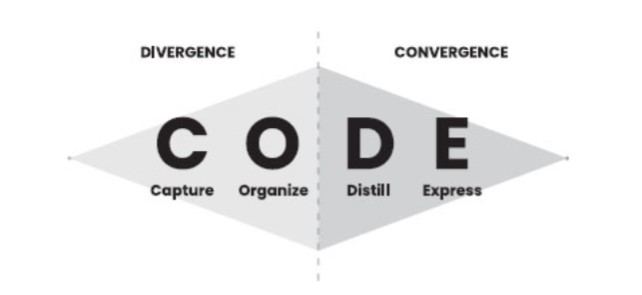

<small>Overlapping ideas of C.O.D.E. and divergence/convergence from Tiago Forte's book

<small>Overlapping ideas of C.O.D.E. and divergence/convergence from Tiago Forte's book