Supplementary Data 3

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-50027-3

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00028994

Supplementary Data 3

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-50027-3

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00028994

Supplementary Data 3

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-50027-3

Resource: (WB Cat# WBStrain00028974,RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00028974)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00028974

CGC

DOI: 10.1007/s13205-024-04017-3

Resource: Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (RRID:SCR_007341)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:SCR_007341

RRID:SCR_014708

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65016-3

Resource: UK Data Archive (RRID:SCR_014708)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:SCR_014708

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors present a variant of a previously described fluorescence lifetime sensor for calcium. Much of the manuscript describes the process of developing appropriate assays for screening sensor variants, and thorough characterization of those variants (inherent fluorescence characteristics, response to calcium and pH, comparisons to other calcium sensors). The final two figures show how the sensor performs in cultured cells and in vivo drosophila brains.

Strengths:

The work is presented clearly and the conclusion (this is a new calcium sensor that could be useful in some circumstances) is supported by the data.

Weaknesses:

There are probably few circumstances where this sensor would facilitate experiments (calcium measurements) that other sensors would prove insufficient.

Comment on revised version:

I think the manuscript has been significantly improved and I concur with the eLife Assessment statement.

[Editors' note: There are no further requests by the reviewers. All of them expressed their approval of the new version of the manuscript.]

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

van der Linden et al. report on the development of a new green-fluorescent sensor for calcium, following a novel rational design strategy based on the modification of the cyan-emissive sensor mTq2-CaFLITS. Through a mutational strategy similar to the one used to convert EGFP into EYFP, coupled with optimization of strategic amino acids located in proximity of the chromophore, they identify a novel sensor, GCaFLITS. Through a careful characterization of the photophysical properties in vitro and the expression level in cell cultures, the authors demonstrate that G-CaFLITS combines a large lifetime response with a good brightness in both the bound and unbound states. This relative independence of the brightness on calcium binding, compared with existing sensors that often feature at least one very dim form, is an interesting feature of this new type of sensors, which allows for a more robust usage in fluorescence lifetime imaging. Furthermore, the authors evaluate the performance of G-CaFLITS in different subcellular compartments and under two-photon excitation in Drosophila. While the data appears robust and the characterization thorough, the interpretation of the results in some cases appears less solid, and alternative explanations cannot be excluded.

Strengths:

The approach is innovative and extends the excellent photophysical properties of the mTq2-based to more red-shifted variants. While the spectral shift might appear relatively minor, as the authors correctly point out, it has interesting practical implications, such as the possibility to perform FLIM imaging of calcium using widely available laser wavelengths, or to reduce background autofluorescence, which can be a significant problem in FLIM.

The screening was simple and rationally guided, demonstrating that, at least for this class of sensors, a careful choice of screening positions is an excellent strategy to obtain variants with large FLIM responses without the need of high-throughput screening.

The description of the methodologies is very complete and accurate, greatly facilitating the reproduction of the results by others, or the adoption of similar methods. This is particularly true for the description of the experimental conditions for optimal screening of sensor variants in lysed bacterial cultures.

The photophysical characterization is very thorough and complete, and the vast amount of data reported in the supporting information is a valuable reference for other researchers willing to attempt a similar sensor development strategy. Particularly well done is the characterization of the brightness in cells, and the comparison on multiple parameters with existing sensors.

Overall, G-CaFLITS displays excellent properties for a FLIM sensor: very large lifetime change, bright emission in both forms and independence from pH in the physiological range.

Weaknesses:

The paper demonstrates the application of G-CaFLITS in various cellular subcompartments without providing direct evidence that the sensor's response is not affected by the targeting. Showing at least that the lifetime values in the saturated state are similar in all compartments would improve the robustness of the claims.

In some cases, the interpretation of the results is not fully convincing, leaving alternative hypotheses as a possibility. This is particularly the case for the claim of the origin of the strongly reduced brightness of G-CaFLITS in Drosophila. The explanation of the intensity changes of G-CaFLITS also shows some inconsistency with the basic photophysical characterization.

While the claims generally appear robust, in some cases they are conveyed with a lack of precision. Several sentences in the introduction and discussion could be improved in this regard. Furthermore, the use of the signal-to-noise ratio as a means of comparison between sensors appears to be imprecise, since it is dependent on experimental conditions.

We thank the reviewer for a thorough evaluation and for suggestions to improve our manuscript. We are happy with the recognition of the strengths of this work. The list with weaknesses has several valid points which will be addressed in a point-by-point reply and a revision.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

Van der Linden et al. describe the addition of the T203Y mutation to their previously described fluorescence lifetime calcium sensor Tq-Ca-FLITS to shift the fluorescence to green emission. This mutation was previously described to similarly red-shift the emission of green and cyan FPs. Tq-Ca-FLITS_T203Y behaves as a green calcium sensor with opposite polarity compared with the original (lifetime goes down upon calcium binding instead of up). They then screen a library of variants at

two linker positions and identify a variant with slightly improved lifetime contrast (TqCa-FLITS_T203Y_V27A_N271D, named G-Ca-FLITS). The authors then characterize the performance of G-Ca-FLITS relative to Tq-Ca-FLITS in purified protein samples, in cultured cells, and in the brains of fruit flies.

Strengths:

This work is interesting as it extends their prior work generating a calcium indicator scaffold for fluorescent protein-based lifetime sensors with large contrast at a single wavelength, which is already being adopted by the community for production of other FLIM biosensors. This work effectively extends that from cyan to green fluorescence. While the cyan and green sensors are not spectrally distinct enough (~20-30nm shift) to easily multiplex together, it at least shifts the spectra to wavelengths that are more commonly available on commercial microscopes.

The observations of organellar calcium concentrations were interesting and could potentially lead to new biological insight if followed up.

Weaknesses:

(1) The new G-Ca-FLITS sensor doesn't appear to be significantly improved in performance over the original Tq-Ca-FLITS, no specific benefits are demonstrated.

(2) Although it was admirable to attempt in vivo demonstration in Drosophila with these sensors, depolarizing the whole brain with high potassium is not a terribly interesting or physiological stimulus and doesn't really highlight any advantages of their sensors; G-Ca-FLITS appears to be quite dim in the flies.

We thank the reviewer for a thorough evaluation and for suggestions to improve our manuscript. Although the spectral shift of the green variant is modest, we have added new data (figure 7) to the manuscript that demonstrates multiplex imaging of G-Ca-FLITS and Tq-Ca-FLITS.

As for the listed weaknesses we respond here:

(1) Although we agree that the performance in terms of dynamic range is not improved, the advantage of the green sensor over the cyan version is that the brightness is high in both states.

(2) We agree that the performance of G-Ca-FLITS is disappointing in Drosophila. We feel that this is important data to report, and it makes it clear that Tq-Ca-FLITS is a better choice for this system. Depolarization of the entire brain was done to measure the maximal lifetime contrast.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

The authours present a variant of a previously described fluorescence lifetime sensor for calcium. Much of the manuscript describes the process of developing appropriate assays for screening sensor variants, and thorough characterization of those variants (inherent fluorescence characteristics, response to calcium and pH, comparisons to other calcium sensors). The final two figures show how the sensor performs in cultured cells and in vivo drosophila brains.

Strengths:

The work is presented clearly and the conclusion (this is a new calcium sensor that could be useful in some circumstances) is supported by the data.

Weaknesses:

There are probably few circumstances where this sensor would facilitate experiments (calcium measurements) that other sensors would prove insufficient.

We thank the reviewer for the evaluation of our manuscript. As for the indicated weakness, we agree that the main application of genetically encoded calcium biosensors is to measure qualitative changes in calcium. However, it can be argued that due to a lack of tools the absolute quantification has been very challenging. Now, thanks to large contrast lifetime biosensors the quantitative measurements are simplified, there are new opportunities, and the probe reported here is an improvement over existing probes as it remains bright in both states, further improving quantitative calcium measurements.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

While the science in the paper appears solid, the methods well grounded and excellently documented, the manuscript would benefit from a revision to improve the clarity of the exposition. In particular:

Part of the introduction appears like a patchwork of information with poor logical consequentiality. The authors rapidly pass from the impact of brightness on FLIM accuracy, to mitochondrial calcium in pathology, to the importance of the sensor's affinity, to a sentence on sensor's kinetics, to fluorescent dyes and bioluminescence, to conclude that sensors should be stable at mitochondrial pH. I highly recommend rewriting this part.

We thank the referee for the comment and we have adjusted to introduction to better connect the parts and increase the logic. The updated introduction addresses all the feedback by the reviewers on different aspects of the introductory text, and we have removed the section on dyes and bioluminescence. We feel that the introduction is better structured now.

The reference to particular amino acid positions would greatly benefit from including images of the protein structure in which the positions are highlighted, similar to what the same authors do in their fluorescent protein development papers. While in the case of sensors a crystal structure might be lacking, highlighting the positions with respect to an AlphaFold-generated structure or the structure of mTq2 might still be helpful.

We appreciate this remark and we have added a sequence alignment of the FLITS probes to supplemental Figure S4. This shows the residues with number, and we have also highlighted the different domains, linkers and mutations. We think that this linear representation works better than a 3D structure (one issue is that alphafold fails to display the chromophore and it has usually poor confidence for linker residues).

The use of SNR, as defined by the authors (mean of the lifetime divided by standard deviation) appears a poorly suited parameter to compare sensors, as it depends on the total number of collected photons and on the strength of the algorithms used to retrieve the lifetime value. In an extreme example, if one would collect uniform images with millions of photons per pixel, most likely SNR would be extremely good for all sensors in all states, irrespective of the fact that some states are dimmer (within reasonable limits). On the other hand, if the same comparison would be performed at a level of thousands or hundreds of photons per pixel, the effect of different brightness on the SNR would be much more dramatic. While in general I fully agree with the core concept of the paper, i.e. that avoiding low-brightness forms leads more easily to experiments with higher SNR, I would suggest to stick to comparing the sensors in terms of brightness and refer to SNR (if needed) only when describing the consequences on measurements.

The reviewer is right that in absolute terms the SNR is not meaningful. In addition to acquisition time, it depends on expression levels. Yet, it is possible to compare the change in SNR between the apo- and saturated states, and that is what is shown in figure 5. We have added text to better explain that the change in SNR is relevant here:

“The absolute SNR is not relevant here, as it will depend on the expression level and acquisition time. But since we have measured the two extremes in the same cells, we can evaluate how the SNR changes between these states for each separate probe”

Some statements from the authors or aspects of the paper appear problematic:

(1) "Additionally, the fluorescence of most sensors is a non-linear function of calcium concentration, usually with Hill coefficients between 2 and 3. This is ideal when the probe is used as a binary detector for increases in Ca2+ concentrations, but it makes robust quantification of low, or even intermediate, calcium concentrations extremely challenging."

To the best of my knowledge, for all sensors the fluorescence response is a nonlinear function of calcium concentrations. If the authors have specific examples in mind in which this is not true, they should cite them specifically. Furthermore, the Hill coefficient defines the range of concentrations in which the sensor operates, while the fact that "low concentrations" might be hard to detect depends only on the dim fluorescence of some sensors in the unbound form.

We agree with the reviewer that this part is not clearly written and confusing, as the sentence “Additionally, the fluorescence of most sensors is a non-linear function of calcium concentration, usually with Hill coefficients between 2 and 3” was not relevant in this section and so we removed it. Now it reads:

“Many GECIs harboring a single fluorescent protein (FP), like GCaMPs, are optimized for a large intensity change, and have a (very) dim state when calcium levels are below the KD of the probe (Akerboom et al., 2013; Dana et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2011). This is ideal when the probe is used as a binary detector for increases in Ca2+ concentrations, but it makes robust quantification of low, or even intermediate, calcium concentrations extremely challenging”

(2) "The affinity of a sensor is of major importance: a low KD can underestimate high concentrations and vice versa."

It is not clear to me why the concentrations would be underestimated, rather than just being less precise. Also, if a calibration curve is plotted in linear scale rather than logarithmic scale, it appears that the precision problem is much more severe near saturation (where low lifetime changes result in large concentration changes) than near zero (where low concentration changes produce large lifetime changes).

We agree that this could be better explained, what we meant to say that concentrations that are ~10x lower or higher than the KD cannot be precisely measured. See also our reply to the next comment.

(3) "Differences can also arise due to the method of calibration, i.e. when the absolute minimum and maximum signal are not reached in the calibration procedure (Fernandez-Sanz et al., 2019)."

Unless better explained, this appears obvious and not worth mentioning.

What may be obvious to the reviewer (and to us) may not be obvious to the reader, and that’s why this is included. To make it clearer we rephrased this part as a list of four items:

“Accurate determination of the affinity of a sensor is important and there are several issues that need to be considered during the calibration and the measurements: (i) the concentrations can only be measured with sufficient precision when it is in the range between 10x K<sub>D</sub> and 1/10x K<sub>D</sub>, (ii) the calibration is only valid when the two extremes are reached during the calibration procedure (Fernandez-Sanz et al., 2019), (iii) the sensor’s kinetics should be sufficiently fast enough to be able to track the calcium changes, and (iv) the biosensor should be compatible with the high mitochondrial pH of 8 (Cano Abad et al., 2004; Llopis et al., 1998).”

(4) In the experiments depicted in Figure 6C the underlying assumption is that the sensor behaves in the same way independently of the compartment to which it is targeted. This is not necessarily the case. It would be valuable to see the plots of Figure 6C and D discussed in terms of lifetime. Is the saturating lifetime value the same in all compartments?

This is a valid point and we have now included a plot with the actual lifetime data for each of the organelles (figure S15).

We have also added text to discuss this point: “We note that the underlying assumption of the quantification of organellar calcium concentrations is that the lifetime contrast is the same. This is broadly true for most of the measurements (Figure S15). Yet, there are also differences. It is currently unclear whether the discrepancies are due to differences in the physicochemical properties of the compartments, or whether there is a technical reason (the efficiency of ionomycin for saturating the biosensor in the different compartments is unknown, as far as we know). This is something that is worth revisiting. A related issue that deserves attention is the level of agreement between in vitro and in vivo calibrations.”

(5) A similar problem arises for the observation of different calcium levels in peripheral mitochondria. In figure S11b, the values of the two lifetime components of a biexponential fit are displayed. Both the long and short components seem to be different. This is an interesting observation, as in an ideal sensor (in which the "long lifetime conformation" is the same whether the sensor is bound to the analyte or not, and similarly for the short lifetime one) those values should be identical. While it is entirely possible that this is not the case for G-CaFLITS, since the authors have conducted a calibration experiment using time-domain FLIM, could they show the behavior of the lifetimes and preamplitudes? Are the trends consistent with their interpretation of a different calcium level in the two mitochondrial populations?

We have analyzed the calibration data from TCSPC experiments done with the Leica Stellaris. From these data (acquired at high photon counts as it is purified protein in solution), we infer that both the short and long lifetime do change as a function of calcium concentration. In particular the long lifetime shows a substantial change, which we cannot explain at this moment. We agree that this is interesting and may potentially give insight in the conformation changes that give rise to the lifetime change.

The lifetime data of the mitochondria has been acquired with a different FLIM setup, but the trend is consistent, both the long and short lifetime decrease in the peripheral mitochondria that have a higher calcium concentration.

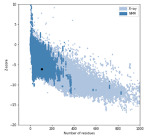

Author response image 1

(6) "The lifetime response of Tq-Ca-FLITS and the ΔF/F response of jGCaMP7f resembled each other, with both signals gradually increasing over the span of 3-4 minutes after we increased external [K+]; the two signals then hit a plateau for ~1 min, followed by a return to baseline and often additional plateaus (Figure 8B-C). By comparison, G-Ca-FLITS responses were more variable, typically exhibiting a smaller ramping phase and seconds-long spikes of activity rather than minutes-long plateaus (Figure 8C)."

This statement does not appear fully consistent with the data in Figure 8. While in figure 8B it looks like GCaMP and mTq-CaFLITS have very similar profiles, these curves come from one single experiment out of a very variable dataset (see Figure 8C). If one would for example choose the second curve of GCaMP in Figure 8C, it would look very similar to the response of G-CaFLITS in figure 8B, and the argument would be reversed. How do the averages look like?

Indeed, the dynamics of the responses are very variable and we do not want to draw attention to these differences in the dynamics, so we have removed the comparison. Instead, the difference in intensity change and lifetime contrast are of importance here. To answer the question of the reviewer, we have added a new panel (D) which shows the average responses for each of the GECIs.

(7) "Although the calibration is equipment independent under ideal conditions, and only needs to be performed once, we prefer to repeat the calibration for different setups to account for differences in temperature or pulse frequency."

While I generally agree with the statement, it is imprecise. A change in temperature is generally expected to affect the Kd, so rather than "preferring to repeat", it is a requirement for accurate quantification at different concentrations. I am not sure I understand what the pulse frequency is in this context, and how it affects the Kd.

We thank the referee for pointing out that our text is imprecise and confusing. What we meant to say is that we see differences between different set-ups and we have clarified this by changing the text. We have also added that it is “necessary” to repeat the calibration:

“Although the calibration is equipment independent under ideal conditions, and only needs to be performed once, we do see differences between different set-ups. Therefore, it is necessary to repeat the calibration for different set-ups.”

(8) "A recent effort to generate a green emitting lifetime biosensor used a GFP variant as a template (Koveal et al., 2022), and the resulting biosensor was pH sensitive in the physiological range. On the other hand, biosensors with a CFP-like chromophore are largely pH insensitive (van der Linden et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2024)."

The dismissal of the use of T-Sapphire as a pH independent template is inaccurate. The same group has previously reported other sensors (SweetieTS for glucose and Peredox for redox ratio) that are not pH sensitive. Furthermore, in Koveal et al. also many of the mTq2-based variants showed a pH response, suggesting that the pHdependence for the Lilac sensor might be more complex. Still, G-CaFLITS present advantages in terms of the possibility to excite at longer wavelengths, which could be mentioned instead.

We only want to make the point that adding the T203Y mutation to Turquoise-based lifetime biosensors may be a good approach for generating pH insensitive green biosensors. There is no point in dismissing other green biosensors and we have changed the text to: “Since biosensors with a CFP-like chromophore are largely pH insensitive (van der Linden et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2024), and we show here that the pH independence is retained for the Green Ca-FLITS, we expect that adding the T203Y mutation to a cyan sensor is a good approach for generating pH-insensitive green lifetime-based sensors.”

(9) "Usually, a higher QY results in a higher intensity; however, in G-Ca-FLITS the open state has a differential shaped excitation spectrum which leads to a decreased intensity. These effects combined have resulted in a sensor where the two different states have a similar intensity despite displaying a large QY and lifetime contrast."

This statement does not seem to reflect the excitation spectra of Figure 1. If this explanation would be true, wouldn't there be an isoemissive point in the excitation spectrum (i.e. an excitation wavelength at which emission intensity would not change)?

The excitation spectra in figure 1 are not ideal for the interpretation as these are not normalized. The normalized spectra are shown in figure S10, but for clarity we show the normalized spectra here below as well. For the FD-FLIM experiments we used a 446 nm LED that excites the calcium bound state more efficiently. Therefore, the lower brightness due to a lower QY of the calcium bound state is compensated by increased excitation. So the limited change in intensity is excitation wavelength dependent. We have added a sentence to the discussion to stress this:

“The smallest intensity change is obtained when the calcium-bound state is preferably excited (i.e. near 450 nm) and the effect is less pronounced when the probe is excited near its peak at 474 nm”

(10) "We evaluated the use of Tq-Ca-FLITS and G-Ca-FLITS for 2P-FLIM and observed a surprisingly low brightness of the green variant in an intact fly brain. This result is consistent with a study finding that red-shifted fluorescent-protein variants that are much brighter under one-photon excitation are, surprisingly, dimmer than their blue cousins in multi-photon microscopy (Molina et al., 2017). The responses of both probes were in line with their properties in single photon FLIM, but given the low brightness of G-Ca-FLITS under 2-photon excitation, the Tq-Ca-FLITS may be a better choice for 2P-FLIM experiments."

The differences appear strikingly high, and it seems improbable that a reduction in two-photon absorption coefficient might be the sole cause. How can the authors rule out a problem in expression (possibly organism-specific)?

The reviewers are correct that the changes in brightness between G-Ca-FLITS and Tq-Ca-FLITS may arise from changes in expression levels. It is difficult to calibrate for these changes explicitly without a stable reference fluorophore. However, both the G-Ca-FLITS and Tq-Ca-FLITS transgenic flies produced used the same plasmid backbone (the Janelia 20x-UAS-IVS plasmid), landed in the same insertion site (VK00005) of the same genetic background and were crossed to the same Janelia driver line (R60D05-Gal4), so at the level of the transcriptional machinery or genetic regulatory landscape the two lines are probably identical except for the few base pair differences between the G-Ca-FLITS and Tq-Ca-FLITS sequence. But the same level of transcription may not correspond to the same amount of stable protein in the ellipsoid body. So, we cannot rule out any organism-specific problems in expression. To examine the 2P excitation efficiency relative to 1P excitation efficiency, we have measured the fluorescence intensity of purified G-Ca-FLITS and Tq-Ca-FLITS on beads. See also response to reviewer 3 and supplemental figure S14

Suggestions

(1) The underlying assumption of any experiment using a biosensor is that the concentration of the biosensor should be roughly 2 orders of magnitude lower than the concentration of the analyte, otherwise the calibration equations do not hold. When measuring nM concentrations of calcium, this problem can be in principle very significant, as the concentration of the sensor in cells is likely in the low micromolar range. Calcium regulation by the cell should compensate for the problem, and the equations should hold. However, this might not hold true during experimental conditions that would disrupt this tight regulation. It might be a good thing to add a sentence to inform users about the limitations in interpreting calcium concentration data under such conditions.

Good point. We have added this to the discussion: “All calcium indicators also act as buffers, and this limits the accuracy of the absolute measurements, especially for the lower calcium concentrations (Rose et al., 2014), as the expression of the biosensor is usually in the low micromolar range.”

(2) Different methods of lifetime "averaging", such as intensity or amplitude-weighted lifetime in time domain FLIM or phase and modulation in frequency domain might lead to different Kd in the same calibration experiment. This is an underappreciated factor that might lead to errors by users. Since the authors conducted calibrations using both frequency and time-domain, it would be useful to mention this fact and maybe add a table in the Supporting Information with the minima, maxima and Kds calculated using different lifetime averaging methods.

To avoid biases due to fitting we prefer to use the phasor plot, this can be used for both frequency and time-domain methods and we added a sentence to the discussion to highlight this: “We prefer to use the phasor analysis (which can be used for both frequency- and time-domain FLIM), as it makes no assumptions about the underlying decay kinetics.”

(3) The origin of the redshift observed in G-CaFLITS is likely pi-stacking, similar to the EGFP-to-EYFP case. While previous studies suggest that for mTq2 based sensors a change in rigidity would lead to a change in the non-radiative rate, which would result in similar changes in quantum yield and (amplitude-weighted average) lifetime. If pi-stacking plays a role, there could be an additional change in the radiative rate (as suggested also by the change in absorption spectra). Could this play a role in the relation between brightness and lifetime in G-CaFLITS? Given the extensive data collected by the authors, it should be possible to comment on these mechanistical aspects, which would be useful to guide future design.

We do appreciate this suggestion, but we currently do not have the data to answer this question. The inverted response that we observe, solely due to the introduction of the tyrosine is puzzling. Perhaps introduction of the mutation that causes the redshift in other cyan probes will provide more insight.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

Specific points:

The first section of Results is basically a description of how they chose the lysis conditions for screening in bacteria. I didn't see anything particularly novel or interesting about this, anyone working with protein expression in bacteria likely needs to optimize growth, lysis, purification, etc. This section should be moved to the Methods.

As reviewer 1 lists the thorough documentation of this approach as one of the strengths, we prefer to keep it like this. We see this section as method development, rather than purely a method. When this section would be moved to methods, it remains largely invisible and we think that’s a shame. Readers that are not interested can easily skip this section.

In the Results section Characterization of G-Ca-FLITS, the authors state "Here, the calcium affinity was KD = 339 nM, higher compared to the calibration at 37{degree sign}C. This is in line with the notion that binding strength generally increases with decreasing temperature." However, the opposite appears to be true - at 37C they measured a KD of 209 nM which would represent higher binding strength at higher temperature.

Thanks for catching this, we’ve made a mistake. We rephrase this to “higher compared to the calibration at 37 ˚C. This is unexpected as it not in line with the notion that binding strength generally increases with decreasing temperature.”

In Figure 8c, there should be a visual indicator showing the onset of application of high potassium, as there is in 8b.

This is a good suggestion; a grey box is added to indicates time when high K+ saline was perfused.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

I think the science of the manuscript is sound and the presentation is logical and clear. I have some stylistic recommendations.

Supp Fig 1: The figure requires a bit of "eyeballing" to decide which conditions are best, and figuring out which spectra matched the final conditions took a little effort. Is there a way to quantify the fluorescence yield to better show why the one set of conditions was chosen? If it was subjective, then at least highlight the final conditions with a box around the spectra, making it a different colour, or something to make it stand out.

Thanks for the comment; we added a green box.

Supp Fig 3: Similar suggestion. Highlight the final variant that was carried forward (T203Y). The subtle differences in spectra are hard to discern when they are presented separately. How would it look if they were plotted all on one graph? Or if each mutant were presented as a point on a graph of Peak Em vs Peak Ex? Would T203Y be in the top right?

We have added a light blue box for reference to make the differences clearer.

Supp Fig 4 & Fig 1: Too much of the graph show the uninteresting tails of the spectra and condenses the interesting part. Plotting from 400 nm to 600 nm would be more informative.

We appreciate the suggestion but disagree. We prefer to show the spectra in its entirety, including the tails. The data will be available so other plots can be made by anyone.

Fig 3a: People who are not experts in lifetime analysis are probably not very familiar with the phase/modulation polar plot. There should be an additional sentence or two in the main text that _briefly_ describes the basis for making the polar plot and the transformation to the fractional saturation plot in 3B. I can't think of a good way to transform Eq 3 from Supp Info into a sentence, but that's what I think is needed to make this transformation clearer.

We appreciate the suggestion and feel that it is well explained here:

"The two extreme values (zero calcium and 39 μM free calcium) are located on different coordinates in the polar plot and all intermediate concentrations are located on a straight line between these two extremes. Based on the position in the polar plot, we determined the fraction of sensor in the calcium-bound state, while considering the intensity contribution of both states"

Fig 4: The figure is great, and I love the comparison of different calcium sensors. But where is Tq-Ca-FLITS? I get that this is a figure of green calcium sensors, but it would be nice to see Tq-Ca-FLITS in there as well. The G-Ca-FLITS is compared to Tq-Ca-FLITS in Fig 5. Maybe I'm just missing why the bottom panel of Fig 5 cannot be replotted and included in Fig 4.

The point is that we compare all the data with identical filter sets, i.e. for green FPs.using these ex/em settings, the Tq probe would seriously underperform. Note that the data in fig. 5 is not normalized to a reference RFP and can therefore not be compared with data presented in figure 4.

Fig 6: The BOEC data could easily be moved to Supp Figs. It doesn't contribute much relevant info.

We are not keen of moving data to supplemental, as too often the supplemental data is ignored. Moreover, we think that the BOEC data is valuable (as BOEC are primary cells and therefore a good model of a healthy human cell) and deserves a place in the main manuscript.

2P FLIM / Fig 8 / Fig S4: The lack of brightness of G-Ca-FLITS in the 2P FLIM of fruit fly brain could have been predicted with a 2P cross section of the purified protein. If the equipment to perform such measurements is available, it could be incorporated into Fig S4.

Unfortunately, we do not have access to equipment that measures the 2P cross section. As an alternative, we compared the 2P excitation efficiency with 1P excitation efficiency. To this end, we have used beads that were loaded with purified G-Ca-FLITS or Tq-Ca-FLITS. We have evaluated the fluorescence intensity of the beads using 1P (460 nm) and 2P (920 nm) excitation. Although the absolute intensity cannot be compared (the G-Ca-FLITS beads have a lower protein concentration), we can compare the relative intensities when changing from 1P to 2P. The 2P excitation efficiency of G-Ca-FLITS is comparable (if not better) to that of Tq-Ca-FLITS. This excludes the option that the G-Ca-FLITS has poor 2P excitability. We will include this data as figure S12.

We also have added text to the results: “We evaluated the relative brightness of purified Tq-Ca-FLITS and G-Ca-FLITS on beads by either 1-Photon Excitation (1PE) (at 460 nm) or 2-Photon Excitation (2PE) (at 920 nm) and observed a similar brightness between the two modes of excitations (figure S14). This shows that the two probes have similar efficiencies in 2PE and suggest that the low brightness of GCa-FLITS in Drosophila is due to lower expression or poor folding.” and discussion: “The responses of both probes were in line with their properties in single photon FLIM, but given the low brightness of G-Ca-FLITS under 2-photon excitation in Drosphila, the Tq-Ca-FLITS is a better choice in this system. Yet, the brightness of G-Ca-FLITS with 2PE at 920 nm is comparable to Tq-Ca-FLITS, so we expect that 2P-FLIM with G-Ca-FLITS is possible in tissues that express it well.”

Await

imagine a waiter (The Event Loop) and a table of customers (The Tasks).

Synchronous (Blocking): The waiter takes an order from Table 1. He walks to the kitchen and stands there waiting for the chef to cook the food. He ignores Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4. Nothing else happens in the restaurant until Table 1 eats.

Asynchronous (await): The waiter takes an order from Table 1 (await food). He gives the ticket to the kitchen. instead of waiting, he immediately turns around and goes to serve Table 2. When the kitchen rings the bell (Task done), he goes back to Table 1.

a. The complementary strand of DNA is: 3'--AATTACCCTGTTCGAACACATCTC--5'

b. The mRNA sequence transcribed from the complementary DNA strand is: 5'--AAU UAC CCU GUC GAA CAC AUC UC--3'

c. Using the genetic code table, the amino acid sequence is: I. Start codon: Met II. Stop codon: Stop

The given DNA sequence is 3' CGTCCACGT 5'.

The complementary strand will be built by pairing the bases: C with G, G with C, T with A, and A with T.

So, the complementary strand is 5' GCAGGTGC 3 I'd use the DNA template strand (3' CGTCCACGT 5'). In RNA, uracil (U) replaces thymine (T).

So, the mRNA sequence will be 5' GCAGGUGCA 3'.

Answer: 5' GCAGGUGCA 3'

. Assembling the Original DNA: You start with a double-stranded DNA molecule. One strand has the sequence 5'-GCAT-3', and it's paired with its complementary strand, which is 3'-CGTA-5'. Remember, A always pairs with T, and G always pairs with C.

Separating the Strands (Helicase): This is like the job of the enzyme DNA helicase. It unwinds and separates the double-stranded DNA into two single strands.

Building Daughter Strands : Each of the original strands now serves as a template for building a new, complementary strand. This is what DNA polymerase does. It adds nucleotides to the 3' end of the new strand, following the base-pairing rules. So, for the template 5'-GCAT-3', the new strand will be 3'-CGTA-5'. And for the template 3'-CGTA-5', the new strand will be 5'-GCAT-3'. Disassembling the Model: This just refers to taking apart the physical model you built to represent the DNA. It's not a step that happens in actual DNA replication in a cell.

Final Answer: DNA replication steps: assembling original DNA, separating strands (helicase), building daughter strands (DNA polymerase), and disassembling the model.

DNA replication is how a DNA molecule makes an exact copy of itself. This is crucial for cell division, ensuring each new cell gets a complete set of genetic instructions.

The process is semi-conservative, meaning each new DNA molecule has one original strand and one newly synthesized strand. This helps reduce errors during copying.

Key steps include: 1. The DNA double helix unwinds. 2. New DNA bases (A, T, G, C) are added to each original strand. 3. Two new DNA molecules are created, each with one old and one new strand.

Several enzymes are involved, including RNA primase, DNA helicase, DNA polymerase, and DNA ligase, each playing a specific role in the process.

It is not within the remit of this paper to examine some of the assumptionsimplicit in the preceding quotation – does the use of standard English really helpdevelop thinking skills, can one only participate in the wider world beyondschool if one speaks in irreproachable standard English, and so on – but we areconcerned to question the validity of the programmes of study developed fromthe above statement of principle. At Key Stages 3 and 4, which cover the period ofschooling with which this paper is concerned, the Programmes of Study for ‘En1Speaking and Listening’ enjoin that in work on Speaking, pupils ‘should betaught to . . . use spoken standard English fluently in different contexts’ (DfEE,1999: 31); there is additionally a separate heading ‘Standard English’ which rules

the paper aims to studly how stander English effects schooling

Author Response:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The work by Wang et al. examined how task-irrelevant, high-order rhythmic context could rescue the attentional blink effect via reorganizing items into different temporal chunks, as well as the neural correlates. In a series of behavioral experiments with several controls, they demonstrated that the detection performance of T2 was higher when occurring in different chunks from T1, compared to when T1 and T2 were in the same chunk. In EEG recordings, they further revealed that the chunk-related entrainment was significantly correlated with the behavioral effect, and the alpha-band power for T2 and its coupling to the low-frequency oscillation were also related to behavioral effect. They propose that the rhythmic context implements a second-order temporal structure to the first-order regularities posited in dynamic attention theory.

Overall, I find the results interesting and convincing, particularly the behavioral part. The manuscript is clearly written and the methods are sound. My major concerns are about the neural part, i.e., whether the work provides new scientific insights to our understanding of dynamic attention and its neural underpinnings.

1) A general concern is whether the observed behavioral related neural index, e.g., alpha-band power, cross-frequency coupling, could be simply explained in terms of ERP response for T2. For example, when the ERP response for T2 is larger for between-chunk condition compared to within-chunk condition, the alpha-power for T2 would be also larger for between-chunk condition. Likewise, this might also explain the cross-frequency coupling results. The authors should do more control analyses to address the possibility, e.g., plotting the ERP response for the two conditions and regressing them out from the oscillatory index.

Many thanks for the comment. In short, the enhancement in alpha power and cross-frequency coupling results in the between-cycle condition compared with those in the within-cycle condition cannot be accounted for by the ERP responses for T2.

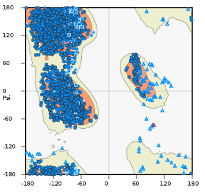

In general, the rhythmic stimulation in the AB paradigm prevents EEG signals from returning to the baseline. Therefore, we cannot observe typical ERP components purely related to individual items, except for the P1 and N1 components related to the stream onset, which reveals no difference between the two conditions and are trailed by steady-state responses (SSRs) resonating at the stimulus rate (Fig. R1).

Fig. R1. ERPs aligned to stream onset. EEG signals were filtered between 1–30 Hz, baseline-corrected (-200 to 0 ms before stream onset) and averaged across the electrodes in left parieto-occipital area where 10-Hz alpha power showed attentional modulation effect.

To further inspect the potential differences in the target-related ERP signals between the within- and between-cycle conditions, we plotted the target-aligned waveforms for these experimental conditions. As shown in Fig. R2, a drop of ERP amplitude occurred for both conditions around T2 onset, and the difference between these two conditions was not significant (paired t-test estimated on mean amplitude every 20 ms from 0 to 700 ms relative to T1 onset, p > .05, FDR-corrected).

Fig. R2. ERPs aligned to T1 onset. EEG signals were filtered between 1–30 Hz, and baseline-corrected using signals -100 to 0 ms before T1 onset. The two dash lines indicate the onset of T1 and T2, respectively.

Since there is a trend of enhanced ERP response for the between-cycle relative to the within-cycle condition during the period of 0 to 100 ms after T2 onset (paired t-test on mean amplitude, p =.065, uncorrected), we then directly examined whether such post-T2 responses contribute to the behavioral attentional modulation effect and behavior-related neural indices. Crucially, we did not find any significant correlation of such T2-related ERP enhancement with the behavioral modulation index (BMI), or with the reported effects of alpha power and cross-frequency coupling (PAC). Furthermore, after controlling for the T2-related ERP responses, there still remains a significant correlation between the delta-alpha PAC and the BMI (rpartial = .596, p = .019), which is not surprising given that the PAC is calculated based on an 800-ms time window covering more pre-T2 than post-T2 periods (see the response to point #4 for details) rather than around the T2 onset. Taken together, these results clearly suggest that the T2-related ERP responses cannot explain the attentional modulation effect and the observed behavior-related neural indices.

2) The alpha-band increase for T2 is indeed contradictory to the well known inhibitory function of alpha-band in attention. How could a target that is better discriminated elicit stronger inhibitory response? Related to the above point, the observed enhancement in alpha-band power and its coupling to low-frequency oscillation might derive from an enhanced ERP response for T2 target.

Many thanks for the comment. We have briefly discussed this point in the revised manuscript (page 18, line 477).

A widely accepted function of alpha activity in attention is that alpha oscillations suppress irrelevant visual information during spatial selection (Kelly et al., 2006; Thut et al., 2006; Worden et al., 2000). However, it becomes a controversial issue when there exists rhythmic sensory stimulation at alpha-band, just like the situation in the current study where both the visual stream and the contextual auditory rhythm were emitted at 10 Hz. In such a case, alpha-band neural responses at the stimulation frequency can be interpreted as either passively evoked steady-state responses (SSR) or actively synchronized intrinsic brain rhythms. From the former perspective (i.e., the SSR view), an increase in the amplitude or power at the stimulus frequency may indicate an enhanced attentional allocation to the stimulus stream that may result in better target detection (Janson et al., 2014; Keil et al., 2006; Müller & Hübner, 2002). Conversely, the latter view of the inhibitory function of intrinsic alpha oscillations would produce the opposite prediction. In a previous AB study, Janson and colleagues (2014) investigated this issue by separating the stimulus-evoked activity at 12 Hz (using the same power analysis method as ours) from the endogenous alpha oscillations ranging from 10.35 to 11.25 Hz (as indexed by individual alpha frequency, IAF). Interestingly, they found a dissociation between these two alpha-band neural responses, showing that the RSVP frequency power was higher in non-AB trials (T2 detected) than in AB trials (T2 undetected) while the IAF power exhibited the opposite pattern. According to these findings, the currently observed increase in alpha power for the between-cycle condition may reflect more of the stimulus-driven processes related to attentional enhancement. However, we don’t negate the effect of intrinsic alpha oscillations in our study, as the current design is not sufficient to distinguish between these two processes. We have discussed this point in the revised manuscript (page 18, line 477). Also, we have to admit that “alpha power” may not be the most precise term to describe our findings of the stimulus-related results. Thus, we have specified it as “neural responses to first-order rhythms at 10 Hz” and “10-Hz alpha power” in the revised manuscript (see page 12 in the Results section and page 18 in the Discussion section).

As for the contribution of T2-related ERP response to the observed effect of 10 Hz power and cross-frequency coupling, please refer to our response to point #1.

References:

Janson, J., De Vos, M., Thorne, J. D., & Kranczioch, C. (2014). Endogenous and Rapid Serial Visual Presentation-induced Alpha Band Oscillations in the Attentional Blink. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26(7), 1454–1468. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00551

Keil, A., Ihssen, N., & Heim, S. (2006). Early cortical facilitation for emotionally arousing targets during the attentional blink. BMC Biology, 4(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-4-23

Kelly, S. P., Lalor, E. C., Reilly, R. B., & Foxe, J. J. (2006). Increases in Alpha Oscillatory Power Reflect an Active Retinotopic Mechanism for Distracter Suppression During Sustained Visuospatial Attention. Journal of Neurophysiology, 95(6), 3844–3851. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01234.2005

Müller, M. M., & Hübner, R. (2002). Can the Spotlight of Attention Be Shaped Like a Doughnut? Evidence From Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials. Psychological Science, 13(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00422

Thut, G., Nietzel, A., Brandt, S., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2006). Alpha-band electroencephalographic activity over occipital cortex indexes visuospatial attention bias and predicts visual target detection. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 26(37), 9494–9502. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0875-06.2006

Worden, M. S., Foxe, J. J., Wang, N., & Simpson, G. V. (2000). Anticipatory Biasing of Visuospatial Attention Indexed by Retinotopically Specific α-Bank Electroencephalography Increases over Occipital Cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 20(6), RC63–RC63. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-j0002.2000

3) To support that it is the context-induced entrainment that leads to the modulation in AB effect, the authors could examine pre-T2 response, e.g., alpha-power, and cross-frequency coupling, as well as its relationship to behavioral performance. I think the pre-stimulus response might be more convincing to support the authors' claim.

Many thanks for the insightful suggestion. We have conducted additional analyses.

Following this suggestion, we have examined the 10-Hz alpha power within the time window of -100–0 ms before T2 onset and found stronger activity for the between-cycle condition than for the within-cycle condition. This pre-T2 response is similar to the post-T2 response except that it is more restricted to the left parieto-occipital cluster (CP3, CP5, P3, P5, PO3, PO5, POZ, O1, OZ, t(15) = 2.774, p = .007), which partially overlaps with the cluster that exhibits a delta-alpha coupling effect significantly correlated with the BMI. We have incorporated these findings into the main text (page 12, line 315) and the Fig. 5A of the revised manuscript.

As for the coupling results reported in our manuscript, the coupling index (PAC) was calculated based on the activity during the second and third cycles (i.e., 400 to 1200 ms from stream onset) of the contextual rhythm, most of which covers the pre-T2 period as T2 always appeared in the third cycle for both conditions. Together, these results on pre-T2 10-Hz alpha power and cross-frequency coupling, as well as its relationship to behavioral performance, jointly suggest that the observed modulation effect is caused by the context-induced entrainment rather than being a by-product of post-T2 processing.

4) About the entrainment to rhythmic context and its relation to behavioral modulation index. Previous studies (e.g., Ding et al) have demonstrated the hierarchical temporal structure in speech signals, e.g., emergence of word-level entrainment introduced by language experience. Therefore, it is well expected that imposing a second-order structure on a visual stream would elicit the corresponding steady-state response. I understand that the new part and main focus here are the AB effects. The authors should add more texts explaining how their findings contribute new understandings to the neural mechanism for the intriguing phenomena.

Many thanks for the suggestion. We have provided more discussion in the revised manuscript (page 17, line 447).

We have provided more discussion on this important issue in the revised manuscript (page 17, line 447). In brief, our study demonstrates how cortical tracking of feature-based hierarchical structure reframes the deployment of attentional resources over visual streams. This effect, distinct from the hierarchical entrainment to speech signals (Ding et al., 2016; Gross et al., 2013), does not rely on previously acquired knowledge about the structured information and can be established automatically even when the higher-order structure comes from a task-irrelevant and cross-modal contextual rhythm. On the other hand, our finding sheds fresh light on the adaptive value of the structure-based entrainment effect by expanding its role from rhythmic information (e.g., speech) perception to temporal attention deployment. To our knowledge, few studies have tackled this issue in visual or speech processing.

References:

Ding, N., Melloni, L., Zhang, H., Tian, X., & Poeppel, D. (2016). Cortical tracking of hierarchical linguistic structures in connected speech. Nature Neuroscience, 19(1), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4186

Gross, J., Hoogenboom, N., Thut, G., Schyns, P., Panzeri, S., Belin, P., & Garrod, S. (2013). Speech Rhythms and Multiplexed Oscillatory Sensory Coding in the Human Brain. PLoS Biol, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001752

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In cognitive neuroscience, a large number of studies proposed that neural entrainment, i.e., synchronization of neural activity and low-frequency external rhythms, is a key mechanism for temporal attention. In psychology and especially in vision, attentional blink is the most established paradigm to study temporal attention. Nevertheless, as far as I know, few studies try to link neural entrainment in the cognitive neuroscience literature with attentional blink in the psychology literature. The current study, however, bridges this gap.

The study provides new evidence for the dynamic attending theory using the attentional blink paradigm. Furthermore, it is shown that neural entrainment to the sensory rhythm, measured by EEG, is related to the attentional blink effect. The authors also show that event/chunk boundaries are not enough to modulate the attentional blink effect, and suggest that strict rhythmicity is required to modulate attention in time.

In general, I enjoyed reading the manuscript and only have a few relatively minor concerns.

1) Details about EEG analysis.

. First, each epoch is from -600 ms before the stimulus onset to 1600 ms after the stimulus onset. Therefore, the epoch is 2200 s in duration. However, zero-padding is needed to make the epoch duration 2000 s (for 0.5-Hz resolution). This is confusing. Furthermore, for a more conservative analysis, I recommend to also analyze the response between 400 ms and 1600 ms, to avoid the onset response, and show the results in a supplementary figure. The short duration reduces the frequency resolution but still allows seeing a 2.5-Hz response.

Thanks for the comments. Each epoch was indeed segmented from -600 to 1600 ms relative to the stimulus onset, but in the spectrum analysis, we only used EEG signals from stream onset (i.e., time point 0) to 1600 ms (see the Materials and Methods section) to investigate the oscillatory characteristics of the neural responses purely elicited by rhythmic stimuli. The 1.6-s signals were zero-padded into a 2-s duration to achieve a frequency resolution of 0.5 Hz.

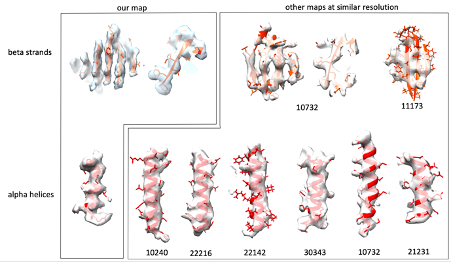

According to the reviewer’s suggestion, we analyzed the EEG signals from 400 ms to 1600 ms relative to stream onset to avoid potential influence of the onset response, and showed the results in Figure 4. Basically, we can still observe spectral peaks at the stimulus frequencies of 2.5, 5 (the harmonic of 2.5 Hz), and 10 Hz for both power and ITPC spectrum. However, the peak magnitudes were much weaker than those of 1.6-s signals especially for 2.5 Hz, and the 2.5-Hz power did not survive the multiple comparisons correction across frequencies (FDR threshold of p < .05), which might be due to the relatively low signal-to-noise ratio for the analysis based on the 1.2-s epochs (only three cycles to estimate the activity at 2.5 Hz). Importantly, we did identify a significant cluster for 2.5 Hz ITPC in the left parieto-occipital region showing a positive correlation with the individuals’ BMI (Fig. R3; CP5, TP7, P5, P7, PO5, PO7, O1; r = .538, p = .016), which is consistent with the findings based on the longer epochs.

Fig. R3. Neural entrainment to contextual rhythms during the period of 400–1600 ms from stream onset. (A) The spectrum for inter-trial phase coherence (ITPC) of EEG signals from 400 to 1600 ms after the stimulus onset. Shaded areas indicate standard errors of the mean. (B) The 2.5-Hz ITPC was significantly correlated with the behavioral modulation index (BMI) in a parieto-occipital cluster, as indicated by orange stars in the scalp topographic map.

Second, "The preprocessed EEG signals were first corrected by subtracting the average activity of the entire stream for each epoch, and then averaged across trials for each condition, each participant, and each electrode." I have several concerns about this procedure.

(A) What is the entire stream? It's the average over time?

Yes, as for the power spectrum analysis, EEG signals were first demeaned by subtracting the average signals of the entire stream over time from onset to offset (i.e., from 0 to 1600 ms) before further analysis. We performed this procedure following previous studies on the entrainment to visual rhythms (Spaak et al., 2014). We have clarified this point in the “Power analysis” part of the Materials and Methods section (page 25, line 677).

References:

Spaak, E., Lange, F. P. de, & Jensen, O. (2014). Local Entrainment of Alpha Oscillations by Visual Stimuli Causes Cyclic Modulation of Perception. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(10), 3536–3544. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4385-13.2014

(B) I suggest to do the Fourier transform first and average the spectrum over participants and electrodes. Averaging the EEG waveforms require the assumption that all electrodes/participants have the same response phase, which is not necessarily true.

Thanks for the suggestion. In an AB paradigm, the evoked neural responses are sufficiently time-locked to the periodic stimulation, so it is reasonable to quantify power estimate with spectral decomposition performed on trial-averaged EEG signals (i.e., evoked power). Moreover, our results of inter-trial phase coherence (ITPC), which estimated the phase-locking value across trials based on single-trial decomposed phase values, also provided supporting evidence that the EEG waveforms were temporally locked across trials to the 2.5-Hz temporal structure in the context session.

Nevertheless, we also took the reviewer’s suggestion seriously and analyzed the power spectrum on the average of single-trial spectral transforms, i.e., the induced power, which puts emphasis on the intrinsic non-phase-locked activities. In line with the results of evoked power and ITPC, the induced power spectrum in context session also peaked at 2.5 Hz and was significantly stronger than that in baseline session at 2.5 Hz (t(15) = 4.186, p < .001, FDR-corrected with a p value threshold < .001). Importantly, Person correlation analysis also revealed a positive cluster in the left parieto-occipital region, indicating the induced power at 2.5 Hz also had strong relevance with the attentional modulation effect (P7, PO7, PO5, PO3; r = .606, p = .006). We have added these additional findings to the revised manuscript (page 11, line 288; see also Figure 4—figure supplement 1).

2) The sequences are short, only containing 16 items and 4 cycles. Furthermore, the targets are presented in the 2nd or 3rd cycle. I suspect that a stronger effect may be observed if the sequence are longer, since attention may not well entrain to the external stimulus until a few cycles. In the first trial of the experiment, they participant may not have a chance to realize that the task-irrelevant auditory/visual stimulus has a cyclic nature and it is not likely that their attention will entrain to such cycles. As the experiment precedes, they learns that the stimulus is cyclic and may allocate their attention rhythmically. Therefore, I feel that the participants do not just rely on the rhythmic information within a trial but also rely on the stimulus history. Please discuss why short sequences are used and whether it is possible to see buildup of the effect over trials or over cycles within a trial.

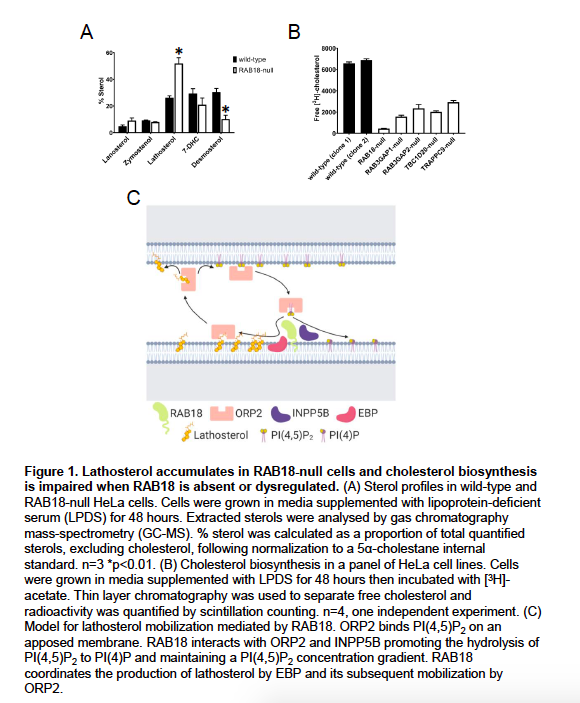

Thanks for the comments. Typically, to induce a classic pattern of AB effect, the RSVP stream should contain 3–7 distractors before the first target (T1), with varying lengths of distractors (0–7) between two targets and at least 2 items after the second target (T2). In our study, we created the RSVP streams following these rules, which allowed us to observe the typical AB effect that T2 performance was deteriorated at Lag 2 relative to that at Lag 8. Nevertheless, we agree with the reviewer that longer streams would be better for building up the attentional entrainment effect, as we did observe the attentional modulation effect ramped up as the stream proceeded over cycles, consistent with the reviewer’s speculation. In Experiments 1a (using auditory context) and 2a (using color-defined visual context), we adopted two sets of target positions—an early one where T2 appeared at the 6th or 8th position (in the 2nd cycle) of the visual stream, and a late one where T2 appeared at the 10th or 12th position (in the 3rd cycle) of the visual stream. In the manuscript, we reported T2 performance with all the target positions combined, as no significant interaction was found between the target positions and the experimental conditions (ps. > .1). However, additional analysis demonstrated a trend toward an increase of the attentional modulation effect over cycles, from the early to the late positions. As shown in Fig. R4, the modulation effect went stronger and reached significance for the late positions (for Experiment 1a, t(15) = 2.83, p = .013, Cohen’s d = 0.707; for Experiment 2a, t(15) = 3.656, p = .002, Cohen’s d = 0.914) but showed a weaker trend for the early positions (for Experiment 1a, t(15) = 1.049, p = .311, Cohen’s d = 0.262; for Experiment 2a, t(15) = .606, p = .553, Cohen’s d = 0.152).

Fig. R4. Attentional modulation effect built up over cycles in Experiments 1a & 2a. Error bars represent 1 SEM; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

However, we did not observe an obvious buildup effect across trials in our study. The modulation effect of contextual rhythms seems to be a quick process that the effect is evident in the first quarter of trials in Experiment 1a (for, t(15) = 2.703, p = .016, Cohen’s d = 0.676) and in the second quarter of trials in Experiment 2a (for, t(15) = 2.478, p = .026, Cohen’s d = 0.620.

3) The term "cycle" is used without definition in Results. Please define and mention that it's an abstract term and does not require the stimulus to have "cycles".

Thanks for the suggestion. By its definition, the term “cycle” refers to “an interval of time during which a sequence of a recurring succession of events or phenomena is completed” or “a course or series of events or operations that recur regularly and usually lead back to the starting point” (Merriam-Webster dictionary). In the current study, we stuck to the recurrent and regular nature of “cycle” in general while defined the specific meaning of “cycle” by feature-based periodic changes of the contextual stimuli in each experiment (page 5, line 101; also refer to Procedures in the Materials and Methods section for details). For example, in Experiment 1a, the background tone sequence changed its pitch value from high to low or vice versa isochronously at a rate of 2.5 Hz, thus forming a rhythmic context with structure-based cycles of 400 ms. Note that we did not use the more general term “chunk”, because arbitrary chunks without the regularity of cycles are insufficient to trigger the attentional modulation effect in the current study. Indeed, the effect was eliminated when we replaced the rhythmic cycles with irregular chunks (Experiments 1d & 1e).

4) Entrainment of attention is not necessarily related to neural entrainment to sensory stimulus, and there is considerable debate about whether neural entrainment to sensory stimulus should be called entrainment. Too much emphasis on terminology is of course counterproductive but a short discussion on these issues is probably necessary.

Thanks for the comments. As commonly accepted, entrainment is defined as the alignment of intrinsic neuronal activity to the temporal structure of external rhythmic inputs (Lakatos et al., 2019; Obleser & Kayser, 2019). Here, we are interested in the functional roles of cortical entrainment to the higher-order temporal structure imposed on first-order sensory stimulation, and used the term entrainment to describe the phase-locking neural responses to such hierarchical structure following literature on auditory and visual perception (Brookshire et al., 2017; Doelling & Poeppel, 2015). In our study, the consistent results of power and ITPC have provided strong evidence that neural entrainment at the structure level (2.5 Hz) is significantly correlated with the observed attentional modulation effect. However, this does not mean that the entrainment of attention is necessarily associated with neural entrainment to sensory stimulus in a broader context, as attention may also be guided by predictions based on non-isochronous temporal regularity without requiring stimulus-based oscillatory entrainment (Breska & Deouell, 2017; Morillon et al._2016).

On the other hand, there has been a debate about whether the neural alignment to rhythmic stimulation reflects active entrainment of endogenous oscillatory processes (i.e., induced activity) or a series of passively evoked steady-state responses (Keitel et al., 2019; Notbohm et al., 2016; Zoefel et al., 2018). The latter process is also referred to as “entrainment in a broad sense” by Obleser & Kayser (2019). Given that a presented rhythm always evokes event-related potentials, a better question might be whether the observed alignment reflects the entrainment of endogenous oscillations in addition to evoked steady-state responses. Here we attempted to tackle this issue by measuring the induced power, which emphasizes the intrinsic non-phase-locked activity, in addition to the phase-locked evoked power. Specifically, we quantified these two kinds of activities with the average of single-trial EEG power spectra and the power spectra of trial-averaged EEG signals, respectively, according to Keitel et al. (2019). In addition to the observation of evoked responses to the contextual structure, we also demonstrated an attention-related neural tracking of the higher-order temporal structure based on the induced power at 2.5 Hz (see Figure 4—figure supplement 1), suggesting that the observed attentional modulation effect is at least partially derived from the entrainment of intrinsic oscillatory brain activity. We have briefly discussed this point in the revised manuscript (page 17, line 460).

References:

Breska, A., & Deouell, L. Y. (2017). Neural mechanisms of rhythm-based temporal prediction: Delta phase-locking reflects temporal predictability but not rhythmic entrainment. PLOS Biology, 15(2), e2001665. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2001665

Brookshire, G., Lu, J., Nusbaum, H. C., Goldin-Meadow, S., & Casasanto, D. (2017). Visual cortex entrains to sign language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(24), 6352–6357. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620350114

Doelling, K. B., & Poeppel, D. (2015). Cortical entrainment to music and its modulation by expertise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(45), E6233–E6242. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1508431112

Henry, M. J., Herrmann, B., & Obleser, J. (2014). Entrained neural oscillations in multiple frequency bands comodulate behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(41), 14935–14940. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1408741111

Keitel, C., Keitel, A., Benwell, C. S. Y., Daube, C., Thut, G., & Gross, J. (2019). Stimulus-Driven Brain Rhythms within the Alpha Band: The Attentional-Modulation Conundrum. The Journal of Neuroscience, 39(16), 3119–3129. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-18.2019

Lakatos, P., Gross, J., & Thut, G. (2019). A New Unifying Account of the Roles of Neuronal Entrainment. Current Biology, 29(18), R890–R905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.075

Morillon, B., Schroeder, C. E., Wyart, V., & Arnal, L. H. (2016). Temporal Prediction in lieu of Periodic Stimulation. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(8), 2342–2347. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0836-15.2016

Notbohm, A., Kurths, J., & Herrmann, C. S. (2016). Modification of Brain Oscillations via Rhythmic Light Stimulation Provides Evidence for Entrainment but Not for Superposition of Event-Related Responses. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00010

Obleser, J., & Kayser, C. (2019). Neural Entrainment and Attentional Selection in the Listening Brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(11), 913–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.08.004

Zoefel, B., ten Oever, S., & Sack, A. T. (2018). The Involvement of Endogenous Neural Oscillations in the Processing of Rhythmic Input: More Than a Regular Repetition of Evoked Neural Responses. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00095

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The current experiment tests whether the attentional blink is affected by higher-order regularity based on rhythmic organization of contextual features (pitch, color, or motion). The results show that this is indeed the case: the AB effect is smaller when two targets appeared in two adjacent cycles (between-cycle condition) than within the same cycle defined by the background sounds. Experiment 2 shows that this also holds for temporal regularities in the visual domain and Experiment 3 for motion. Additional EEG analysis indicated that the findings obtained can be explained by cortical entrainment to the higher-order contextual structure. Critically feature-based structure of contextual rhythms at 2.5 Hz was correlated with the strength of the attentional modulation effect.

This is an intriguing and exciting finding. It is a clever and innovative approach to reduce the attention blink by presenting a rhythmic higher-order regularity. It is convincing that this pulling out of the AB is driven by cortical entrainment. Overall, the paper is clear, well written and provides adequate control conditions. There is a lot to like about this paper. Yet, there are particular concerns that need to be addressed. Below I outline these concerns:

1) The most pressing concern is the behavioral data. We have to ensure that we are dealing here with a attentional blink. The way the data is presented is not the typical way this is done. Typically in AB designs one see the T2 performance when T1 is ignored relative to when T1 has to be detected. This data is not provided. I am not sure whether this data is collected but if so the reader should see this.

Many thanks for the suggestion. We appreciate the reviewer for his/her thoughtful comments. To demonstrate the AB effect, we did include two T2 lag conditions in our study (Experiments 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b)—a short-SOA condition where T2 was located at the second lag of T1 (i.e., SOA = 200 ms), and a long-SOA condition where T2 appeared at the 8th lag of T1 (i.e., SOA = 800 ms). In a typical AB effect, T2 performance at short lags is remarkably impaired compared with that at long lags. In our study, we consistently replicated this effect across the experiments, as reported in the Results section of Experiment 1 (page 5, line 106). Overall, the T2 detection accuracy conditioned on correct T1 response was significantly impaired in the short-SOA condition relative to that in the long-SOA condition (mean accuracy > 0.9 for all experiments), during both the context session and the baseline session. More crucially, when looking into the magnitude of the AB effect as measured by (ACClong-SOA - ACCshort-SOA)/ACClong-SOA, we still obtained a significant attentional modulation effect (for Experiment 1a, t(15) = -2.729, p = .016, Cohen’s d = 0.682; for Experiment 2a, t(15) = -4.143, p <.001, Cohen’s d = 1.036) similar to that reflected by the short-SOA condition alone, further confirming that cortical entrainment effectively influences the AB effect.

Although we included both the long- and short-SOA conditions in the current study, we focused on T2 performance in the short-SOA condition rather than along the whole AB curve for the following reasons. Firstly, for the long-SOA conditions, the T2 performance is at ceiling level, making it an inappropriate baseline to probe the attentional modulation effect. We focused on Lag 2 because previous research has identified a robust AB effect around the second lag (Raymond et al., 1992), which provides a reasonable and sensitive baseline to probe the potential modulation effect of the contextual auditory and visual rhythms. Note that instead of using multiple lags, we varied the length of the rhythmic cycles (i.e., a cycle of 300 ms, 400 ms, and 500 ms corresponding to a rhythm frequency of 3.3 Hz, 2.5 Hz, and 2 Hz, respectively, all within the delta band), and showed that the attentional modulation effect could be generalized to these different delta-band rhythmic contexts, regardless of the absolute positions of the targets within the rhythmic cycles.

As to the T1 performance, the overall accuracy was very high, ranging from 0.907 to 0.972, in all of our experiments. The corresponding results have been added to the Results section of the revised manuscript (page 5, line 103). Notably, we did not find T1-T2 trade-offs in most of our experiments, except in Experiment 2a where T1 performance showed a moderate decrease in the between-cycle condition relative to that in the within-cycle condition (mean ± SE: 0.888 ± 0.026 vs. 0.933 ± 0.016, respectively; t(15) = -2.217, p = .043). However, by examining the relationship between the modulation effects (i.e., the difference between the two experimental conditions) on T1 and T2, we did not find any significant correlation (p = .403), suggesting that the better performance for T2 was not simply due to the worse performance in detecting T1.

Finally, previous studies have shown that ignoring T1 would lead to ceiling-level T2 performance (Raymond et al., 1992). Therefore, we did not include such manipulation in the current study, as in that case, it would be almost impossible for us to detect any contextual modulation effect.

References:

Raymond, J. E., Shapiro, K. L., & Arnell, K. M. (1992). Temporary suppression of visual processing in an RSVP task: An attentional blink? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(3), 849–860. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.18.3.849

2) Also, there is only one lag tested. The ensure that we are dealing here with a true AB I would like to see that more than one lag is tested. In the ideal situation a full AB curve should be presented that includes several lags. This should be done for at least for one of the experiments. It would be informative as we can see how cortical entrainment affects the whole AB curve.

Many thanks for the suggestion. Please refer to our response to the point #1 for “Reviewer #3 (Public Review)”. In short, we did include two T2 lag conditions in our study (Experiments 1a, 1b, 2a and 2b), and the results replicated the typical AB effect. We have clarified this point in the revised manuscript (page 5, line 106).

3) Also, there is no data regarding T1 performance. It is important to show that this the better performance for T2 is not due to worse performance in detecting T1. So also please provide this data.

Many thanks for the suggestion. Please refer to our response to the point #1 or “Reviewer #3 (Public Review)”. We have reported the T1 performance in the revised manuscript (page 5, line 103), and the results didn’t show obvious T1-T2 trade-offs.

4) The authors identify the oscillatory characteristics of EEG signals in response to stimulus rhythms, by examined the FFT spectral peaks by subtracting the mean power of two nearest neighboring frequencies from the power at the stimulus frequency. I am not familiar with this procedure and would like to see some justification for using this technique.

According to previous studies (Nozaradan, 2011; Lenc e al., 2018), the procedure to subtract the average amplitude of neighboring frequency bins can remove unrelated background noise, like muscle activity or eye movement. If there were no EEG oscillatory responses characteristic of stimulus rhythms, the amplitude at a given frequency bin should be similar to the average of its neighbors, and thus no significant peaks could be observed in the subtracted spectrum.

References: