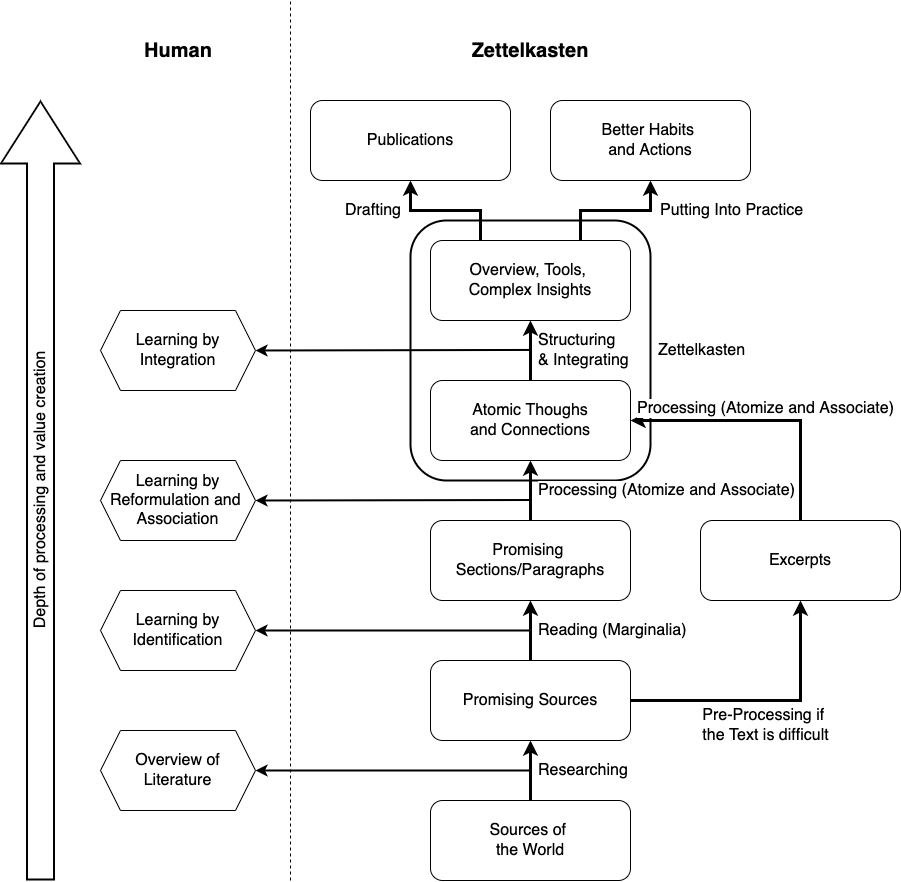

nvolatile solutes do not have an appreciable vapor pressure of their own, and they decrease the vapor pressure of a solvent (over a solution) when added to a solvent. This can be understood by the dynamics depicted in figure 13.5.2. In part (a) you have a pure volatile substance (solvent) and the vapor pressure (Po) is the equilibrium pressure of the solvent when the rate of evaporation equals the rate of condensation (review 11.6, Vapor Pressure as Equilibrium Pressure). Note there are 5 red lines representing the evaporating molecules and 5 black lines representing the condensing molecules (so the rate of condensation equals evaporation and the number of vapor molecules is constant). A non-volatile solute is introduced (b), and when a solute molecule is near the surface it can't escape. This effectively reduces the surface area for evaporation, and so fewer molecules transfer to the vapor phase, but those condensing have no such reduction in surface area (a vaporized solvent molecule can lose energy and condense if it his a surface solute or solvent molecule). So in (b) there are 6 black arrows entering the liquid, but only 4 red arrows leaving. The system is no longer at equilibrium and more solute condense than evaporate, reducing the vapor pressure until the rate of evaporation equals condensation and a new equilibrium has been reached (c). The result is a reduction in t

This makes sense as adding a solute will increase density, making it harder for particles to escape. But this also seems wrong because adding salt to water lowers the boiling point, which in theory should increase vapor pressure and decrease the enthalpy of vaporization.