Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This manuscript presents and analyzes a novel calcium-dependent model of synaptic plasticity combining both presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms, with the goal of reproducing a very broad set of available experimental studies of the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) vs. long-term depression (LTD) in a single excitatory mammalian synapse in the hippocampus. The stated objective is to develop a model that is more comprehensive than the often-used simplified phenomenological models, but at the same time to avoid biochemical modeling of the complex molecular pathways involved in LTP and LTD, retaining only its most critical elements. The key part of this approach is the proposed "geometric readout" principle, which allows to predict the induction of LTP vs. LTD by examining the concentration time course of the two enzymes known to be critical for this process, namely (1) the Ca2+/calmodulin-bound calcineurin phosphatase (CaN), and (2) the Ca2+/calmodulin-bound protein kinase (CaMKII). This "geometric readout" approach bypasses the modeling of downstream pathways, implicitly assuming that no further biochemical information is required to determine whether LTP or LTD (or no synaptic change) will arise from a given stimulation protocol. Therefore, it is assumed that the modeling of downstream biochemical targets of CaN and CaMKII can be avoided without sacrificing the predictive power of the model. Finally, the authors propose a simplified phenomenological Markov chain model to show that such "geometric readout" can be implemented mechanistically and dynamically, at least in principle.

Importantly, the presented model has fully stochastic elements, including stochastic gating of all channels, stochastic neurotransmitter release and stochastic implementation of all biochemical reactions, which allows to address the important question of the effect of intrinsic and external noise on the induction of LTP and LTD, which is studied in detail in this manuscript.

Mathematically, this modeling approach resembles a continuous stochastic version of the "liquid computing" / "reservoir computing" approach: in this case the "hidden layer", or the reservoir, consists of the CaMKII and CaM concentration variables. In this approach, the parameters determining the dynamics of these intermediate ("hidden") variables are kept fixed (here, they are constrained by known biophysical studies), while the "readout" parameters are being trained to predict a target set of experimental observations.

Strengths:

1) This modeling effort is very ambitious in trying to match an extremely broad array of experimental studies of LTP/LTD induction, including the effect of several different pre- and post-synaptic spike sequence protocols, the effect of stimulation frequency, the sensitivity to extracellular Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations and temperature, the dependence of LTP/LTD induction on developmental state and age, and its noise dependence. The model is shown to match this large set of data quite well, in most cases.

2) The choice for stochastic implementation of all parts of the model allows to fully explore the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic noise on the induction of LTP/LTD. This is very important and commendable, since regular noise-less spike firing induction protocols are not very realistic, and not every relevant physiologically.

3) The modeling of the main players in the biochemical pathways involved in LTP/LTD, namely CaMKII and CaN, aims at sufficient biological realism, and as noted above, is fully stochastic, while other elements in the process are modeled phenomenologically to simplify the model and reveal more clearly the main mechanism underlying the LTP/LTD decision switch.

4) There are several experimentally verifiable predictions that are proposed based on an in-depth analysis of the model behavior.

Weaknesses:

1) The stated explicit goal of this work is the construction of a model with an intermediate level of detail, as compared to simplified "one-dimensional" calcium-based phenomenological models on the one hand, and comprehensive biochemical pathway models on the other hand. However, the presented model comes across as extremely detailed nonetheless. Moreover, some of these details appear to be avoidable and not critical to this work. For instance, the treatment of presynaptic neurotransmitter release is both overly detailed and not sufficiently realistic: namely, the extracellular Ca2+ concentration directly affects vesicle release probability but has no effect on the presynaptic calcium concentration. I believe that the number of parameters and the complexity in the presynaptic model could be reduced without affecting the key features and findings of this work.

2) The main hypotheses and assumptions underlying this work need to be stated more explicitly, to clarify the main conclusions and goals of this modeling work. For instance, following much prior work, the presented model assumes that a compartment-based (not spatially-resolved) model of calcium-triggered processes is sufficient to reproduce all known properties of LTP and LTD induction and that neither spatially-resolved elements nor calcium-independent processes are required to predict the observed synaptic change. This could be stated more explicitly. It could also be clarified that the principal assumption underlying the proposed "geometric readout" mechanisms is that all information determining the induction of LTP vs. LTP is contained in the time-dependent spine-averaged Ca2+/calmodulin-bound CaN and CaMKII concentrations, and that no extra elements are required. Further, since both CaN and CaMKII concentrations are uniquely determined by the time course of postsynaptic Ca2+ concentration, the model implicitly assumes that the LTP/LTD induction depends solely on spine-averaged Ca2+ concentration time course, as in many prior simplified models. This should be stated explicitly to clarify the nature of the presented model.

3) In the Discussion, the authors appear to be very careful in framing their work as a conceptual new approach in modeling STD/STP, rather than a final definitive model: for instance, they explicitly discuss the possibility of extending the "geometric readout" approach to more than two time-dependent variables, and comment on the potential non-uniqueness of key model parameters. However, this makes it hard to judge whether the presented concrete predictions on LTP/LTD induction are simply intended as illustrations of the presented approach, or whether the authors strongly expect these predictions to hold. The level of confidence in the concrete model predictions should be clarified in the Discussion. If this confidence level is low, that would call into question the very goal of such a modeling approach.

4) The authors presented a simplified mechanistic dynamical Markov chain process to prove that the "geometric readout" step is implementable as a dynamical process, at least in principle. However, a more realistic biochemical implementation of the proposed "region indicator" variables may be complex and not guaranteed to be robust to noise. While the authors acknowledge and touch upon some of these issues in their discussion, it is important that the authors will prove in future work that the "geometric readout" is implementable as a biochemical reaction network. Barring such implementation, one must be extra careful when claiming advantages of this approach as compared to modeling work that attempts to reconstruct the entire biochemical pathways of LTP/LTD induction.

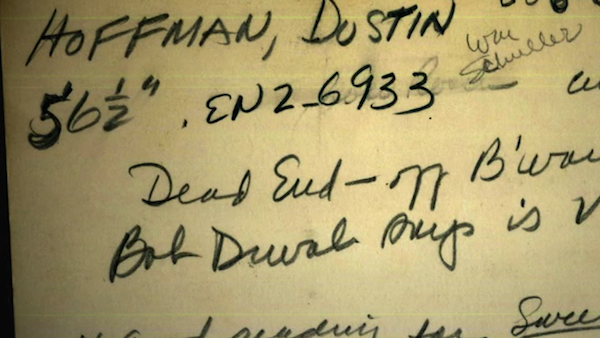

Screen capture from the movie

Screen capture from the movie