Meet the Man Keeping Antique Clocks Ticking | Before it’s Gone Episode 6

Generally two types of clocks:<br /> - spring wound<br /> - weight based

Meet the Man Keeping Antique Clocks Ticking | Before it’s Gone Episode 6

Generally two types of clocks:<br /> - spring wound<br /> - weight based

Westclox Style 5 Big Ben Electric Chime Alarm Introductory Ad by [[Bill Stoddard]]

Clock, Watch and Document Database by [[Bill Stoddard]]

In his 1937 bestseller, The Importance of Living, Lin cautioned: ‘The tempo of modern industrial life … imposes upon us a different conception of time as measured by the clock, and eventually turns the human being into a clock himself’ (pp. 168–69).

for - climate crisis - Youtube - climate Doomsday 6 years from now - Jerry Kroth - to - climate clock - adjacency - Tipping Point Festival - Indyweb / SRG complexity mapping tool - Integration of many fragmented bottom-up initiatives - The Great Weaving - Cosmolocal organization - Michel Bauwens - Peer-to-Peer Foundation - A third option - Islands of Coherency - Otto Scharmer Presencing Institute - U-labs - Love-based (sacred-based) mini-assemblies interventions to address growing fascism, populism and polarization - Roger Hallam - Ending the US / China Cold War - Yanis Varoufakis

YouTube details - title: climate Doomsday 6 years from now - author: Jerry Kroth, pyschologist

summary - Psychologist Jerry Kroth makes a claim that the 1.5 Deg C and 2.0 Deg C thresholds will be reached sooner than expected - due to acceleration of climate change impacts. - He backs up his argument with papers and recent talks of climate thought leaders using their youtube presentations. - This presentation succinctly summarized a lot of the climate news I've been following recently. - It reminded me of the urgency of climate change, my work trying to find a way to integrate the work of the Climate Clock project into other projects. - This work was still incomplete but now I have incentive to complete it.

adjacency - between - Tipping Point Festival - Indyweb / SRG complexity mapping tool - Integration of many fragmented bottom-up initiatives - The Great Weaving - Cosmolocal organization - Michel Bauwens - Peer-to-Peer Foundation - Islands of Coherency - Otto Scharmer - Presencing Institute - U-labs - Love-based (sacred-based) mini-assemblies interventions to address growing fascism, populism and polarization - Roger Hallam - Ending the US / China Cold War - Yanis Varoufakis - and many others - adjacency relationship - I have been holding many fragmented projects in my mind and they are all orbiting around the Tipping Point Festival for the past decade. - When Indyweb Alpha is done, - especially with the new Wikinizer update - We can collectively weave all these ideas together into one coherent whole using Stop Reset Go complexity mapping as a plexmarked Mark-In notation - Then apply cascading social tipping point theory to invite each project to a form a global coherent, bottom-up commons-based movement for rapid whole system change - Currently, there are a lot of jigsaw puzzle pieces to put together! - I think this video served as a reminder of the urgency emerged of our situation and it emerged adjacencies and associations between recent ideas I've been annotating, specifically: - Yanis Varoufakis - Need to end the US-led cold war with China due to US felt threat of losing their US dollar reserve currency status - that Trump wants to escalate to the next stage with major tariffs - MIchel Bauwens - Cosmolocal organization as an alternative to current governance systems - Roger Hallam - love-based strategy intervention for mitigating fascism, polarization and the climate crisis - Otto Scharmer - Emerging a third option to democracy - small islands of coherency can unite nonlinearly to have a significant impact - Climate Clock - a visual means to show how much time we have left - It is noteworthy that: - Yanis Varoufakis and Roger Hallam are both articulating a higher Common Human Denominator - creating a drive to come together rather than separate - which requires looking past the differences and into the fundamental similarities that make us human - the Common Human Denominators (CHD) - In both of their respective articles, Yanis Varoufakis and Otto Scharmer both recognize the facade of the two party system - in the backend, it's only ruled by one party - the oligarchs, the party of the elites (see references below) - Once Indyweb is ready, and SRG complexity mapping and sense-making tool applied within Indyweb, we will already be curating all the most current information from all the fragmented projects together in one place regardless of whether any projects wants to use the Indyweb or not - The most current information from each project is already converged, associated and updated here - This makes it a valuable resource for them because it expands the reach of each and every project

to - climate clock - https://hyp.is/R_kJHKGQEe28r-doGn-djg/climateclock.world/ - love-based intervention to address fascism, populism and polarization - Roger Hallam - https://hyp.is/wUDpaKsAEe-DM9fteMUtzw/www.youtube.com/watch?v=AiKWCHAcS7E - ending the US / China cold war - Yanis Varoufakis - https://hyp.is/Yy0juqmrEe-ERhtaafWWHw/www.youtube.com/watch?v=8BsAa_94dao - Cosmolocal coordination of the commons as an alternative to current governance and a leverage point to unite fragmented communities - Michel Bauwens - https://hyp.is/AvtJYqitEe-f_EtI6TJRVg/4thgenerationcivilization.substack.com/p/a-global-history-of-societal-regulation - A third option for democracy - Uniting small islands of coherency in a time of chaos - Otto Scharmer - https://hyp.is/JlLzuKusEe-xkG-YfcRoyg/medium.com/presencing-institute-blog/an-emerging-third-option-reclaiming-democracy-from-dark-money-dark-tech-3886bcd0469b - One party system - oligarchs - Yanis Varoufakis - https://hyp.is/CVXzAKnWEe-PBBcP5GE8TA/www.youtube.com/watch?v=8BsAa_94dao - What's missing is a third option (in the two party system) - Otto Scharmer - https://hyp.is/M3S6VKuxEe-pG-Myu6VW1A/medium.com/presencing-institute-blog/an-emerging-third-option-reclaiming-democracy-from-dark-money-dark-tech-3886bcd0469b

Derailed climate action: Mr. Trump will almost certainly withdraw again from the 2015Paris Climate Agreement, dismantle domestic climate and environmental regulations(particularly those seen to hamper the fossil fuel industry), and actively oppose atransition to green energy.

for - question - Study on 2024 Trump win on polycrisis - Cascade Institute - why is there such a small analysis on the environment and especially planetary tipping points whilst climate clock is ticking?

1:02:29 The national debt is a historical record of the cumulative money that a government spent dollars than it took out which were transformed into US Treasuries

5:35 Rename Debt clock as savings clock Use of COHERENT Words instead of INCOHERENT Words

clocks enabled the division of time

MERKLE-CLOCKS

we now have a decade—if that—to achieve a dramatic redirection of thehuman course as a now globally interdependentspecies.

for: ecological civilization, climate emergency, climate EMERGEncy inner/outer transformation, eco civilization, rapid whole system change

Title

you may have seen last week that the global carbon budget to 00:11:43 have a chance of holding 1.5 was cut by half so no longer 500 billion tons of carbon dioxide but rather 250 billion tons of carbon dioxide remaining to have a chance of holding 1.5 that's only like 00:11:56 six seven years under current burning of fossil fuels so an orderly phase out means that we really need to start bending the curve immediately and reduce emissions by in the order of six to seven percent per year to have a net 00:12:09 Seer World economy between 2014 and 2050

Using Time.now (which returns the wall-clock time) as base-lines has a couple of issues which can result in unexpected behavior. This is caused by the fact that the wallclock time is subject to changes like inserted leap-seconds or time slewing to adjust the local time to a reference time. If there is e.g. a leap second inserted during measurement, it will be off by a second. Similarly, depending on local system conditions, you might have to deal with daylight-saving-times, quicker or slower running clocks, or the clock even jumping back in time, resulting in a negative duration, and many other issues. A solution to this issue is to use a different time of clock: a monotonic clock.

Antique Calculagraph Machine Time Clock Card Recorder Old Factory Punch Vintage

https://www.ebay.com/itm/293124175605

For advertisement from 1906, see: https://hypothes.is/a/OGREvL98Ee2mYVO2Fqim6Q

Korman, Maria, Vadim Tkachev, Cátia Reis, Yoko Komada, Shingo Kitamura, Denis Gubin, Vinod Kumar, and Till Roenneberg. ‘COVID-19-Mandated Social Restrictions Unveil the Impact of Social Time Pressure on Sleep and Body Clock’. Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (17 December 2020): 22225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79299-7.

The Phases Should Reflect Social Rather Than Objective Time Giddens (I 987), although not the first, makes an important theoretical distinction between social and objective time. Giddens defines clock time as the use of quantified units. Clock time represents "day-to-day" structured activities. Typically, studies refer to disaster phases with hours, days, weeks, or years. Social time, however, is contingent upon the needs or opportunities of a society.

Cites Giddens here to describe differences between social time (sturcturation) and clock time.

These same requirements exist in distributed computing, in which tasks need to be scheduled so that they can be completed in the correct sequence and in a timely manner, with data being transferred between computing elements appropriately.

time factors in crowd work include speed, scheduling, and sequencing

Major societal transformations are linked to information and communication technologies, giving rise to processes of growing global interdependence. They in turn generate the approxi-mation of coevalness, the illusion of simultaneity by being able to link instantly people and places around the globe. Many other processes are also accelerated. Speed and mobility are thus gaining in momentum, leading in turn to further speeding up processes that interlink the move-ment of people, information, ideas and goods.

Evokes Virilio theories and social/political critiques on speed/compression, as cited by Adam (2004).

Also Hassan's work, also cited by Adam (2004).

Despite the apparent diversity of themes, certain common patterns can be discerned in empirical studies dealing with time. They bear the imprint of the ups and downs of research fashions as well as the waxing and waning of influences from neighbouring disciplines. But they all acknowledge 'time as a problem' in 'time-compact' societies (Lenntorp, 1978), imbued with the pressures of time that come from time being a scarce resource.

Overview of interdisciplinary, empirical time/temporality studies from late 70s to 80s. (contemporary to this book)

Cites Carey "The Case of the Telegraph" -- "impact of the telegraph on the standardization of time"

Cites Bluedorn -- "it is omnipresent indecision-making, deadlines andother aspects of organizational behaviour like various forms of group processes"

Another strategy in dealing with sui generis time consists in juxtaposing clock time to the various forms of 'social time' and considers the latter as the more 'natural' ones, i.e. closer to subjective perceptions of time, or to the temporality that results from adaptations to seasons or other kinds of natural (biological, environmental) rhythm. This strategy, often couched also in terms of an opposition between 'linear' clock time and 'cyclical' time of natural and social rhythms devalues, or at least ques-tions, the temporality of formal organizations which rely heavily on clock time in fulfilling their coordinative and integrative and controlling functions (Young, 1988; Elchardus, 1988).

by contrasting social time (as a natural phenomenon) against clock time, allows for a more explicit perspective on linear time (clock) and social rhythms when examining social coordination.

In other words, the idea of time as socially constituted depends fundamentally on the meaning we impose on 'the social', whether we understand it as a prerogative of human social organisation or, following Mead, as a principle of nature.

In a long prior passage about how time is conceptualized in nature and in social coordination, Adam argues that "time" as a social construct should be thought of holistically and not broken into dichotomies to be compared/contrasted.

A brief expansion of these general social science assumptions about nature will clarify this point. Nature as distinct from social life is understood to be quantifiable, simple, and subject to invariant relations and laws that hold beyond time and space (Giddens 1976; Lessnoff 1979· ~yan 1979). This view is accompanied by an understanding of natural time as coming in fixed, divisible units that can be measured whilst quality, complexit~, ~nd mediating knowledge are preserved exclusively for the conceptuahsat10n of human social time. On the basis of a further closely related idea it is proposed that nature may be understood objectively. Natural scientists, explain Elias (1982a, b) and Giddens ( 1976), stand in a subject-object relationship to their subject matter. Natural scientists, they suggest, are able to study objects directly and apply a causal framework of analysis whilst such direct causal links no longer suffice for the study of human society where that which is investigated has to be appreciated as unintended outcomes of intended actions and where the investigators interpret a pre-interpreted world. Unlike their colleagues in the natural sciences, social scientists, it is argued, stand in a subject-subject relation to their subject matter. In a?ditio? to the differences along the quantity-quality and object-subject d1mens10ns nature is thought to be predictable because its regularities -be they causal, statistical, or probabilistic -are timeless. The laws of nature. are c?nsi~ered to be true in an absolute and timeless way, the laws of society h1stoncally developed. In contrast to nature, human societies are argued to be fundamentally historical. They are organised around :alues, goals, morals, ethics, and hopes, whilst simultaneously being mfl~enc~d by tradition, habits, and legitimised meanings.

Critique of flawed social science perception of natural science as driven by laws, order, and quantitative attributes (subject-object) that are observable. This is contrasted with perception about social science as driven by history, culture, habit, and meanings which are socially constructed qualitative attributes (subject-subject).

Since our traditional understanding of natural time e~erged as inadequate and faulty we have to recognise that the analysis of social time is flawed by implication.

Adam states that "social time" theories should be contested since social science disciplinary understanding of "natural time" is incorrect.

Past, present, and future, historical time, the qualitative experience of time, the structuring of 'undifferentiated change' i?to episodes, all are established as integral time aspects of the subJect matter of the natural sciences and clock time, the invariant measure, the closed circle, the perfect symmetry, and reversible time as our creations.

Adam's broader definition of "natural time" which is socially constructed and not just a physical phenomena.

Sorokin and Merton (1937) may be said to have provided the 'definitive' classic statement on the distinction between social and natural time. They associate the physical time of diurnal and seasonal cycles with clock time and define this time as 'purely quantitative, shorn of qualitative variation' (p. 621). 'All time systems', Sorokin and Merton suggest further, 'may be reduced to the need of providing means for synchronising and co-ordinating the activities and observations of the constituents of groups' (p. 627).

classic definition of "social time" vs "natural time". This thinking is now contested.

Whilst social theorists are no longer united in the belief that all time systems are reducible to the functional need of human synchro~is_ation and co-ordination they seem to have little doubt about the validity of Sorokin and Merton's other key point that, unlike social time, the time of nature is that of the clock, a time characterised by invariance and quantity. Despite significant shifts in the understanding of social time, the assumptions about nature, natural time, and the subject matter of the natural sciences have remained largely unchanged.

Adam argues here that while the concept of "social time" has evolved, social scientists' ideas around "natural time" have not kept pace with new scientific research, and incorrectly continue to be described as constant and quantitative (aka clock time).

Further, "natural time" incorrectly incorporates other temporal experiences and seems to be used as a convenient counter foil to "social time"

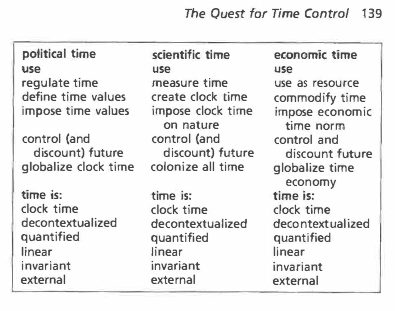

It shows thar irrespective of the diverse temporal uses of time in the political, scientific and economic spheres, a unified clock time underpins the differences in expressions. All other forms of temporal relations are refracted through chis created temporal form, or at least touched by its pervasive dominance

Clock-time dominates political, scientific and economic practices despite the very different ways temporality is represented in these fields.

This industrial norm, as I suggested above, is fundamentally rooted in clock time and underpinned by naturalized assumptions about not just the capacity but also the need to commodify, compress and control time.

'Interconnectivity', Hassan suggests, 'is what gives the network time its power within culture and society.'32 It is worth quoting him at length here. Network time does not 'kill' or render 'timeless' other temporalities, clock-time or otherwise. The embedded nature of the 'multiplicity' of temporalities rbat pervade culture and society, and tbe deeply intractable relationship we have with rhe clock make this unlikely. Rather, the process is one of 'displacement'. Network time constitutes a new and powerful temporality that is beginning to displace, neutralise, sublimate and otherwise upset other temporal relationships in our work, home and leisure environments

Hassan advances Castells' work on network time and focuses on how the cultural impact/power comes from interconnectivity of the network, not Virilio's emphasis on communication speed.

In this view, culture and society have multiple temporalities that layer/modify/supercede as globalization, political/work trends, and new technologies take hold.

Network time is displacing other types of temporal representations, like clock-time.

In a systematic analysis Castells contrasts the clock time of modernity with the network time of the network society.

clock time vs network time

Definition of network time, per Hassan (2003): "Through the convergence of neoliberal globalization and ICT revolution a new powerful temporality has emerged through which knowledge production is refracted: network time."

While interest and credit had been known and documented since 3000 BC in Babylonia, it was not until the late Middle Ages that the Christian Church slowly and almost surreptitiously changed its position on usury,6 which set time free for trade to be allocated, sold and controlled. It is against this back�round that we have to read the extr�cts from Benjar1_1in Franklin's text of 1736, quoted at length m chapter 2, which contains the famous phrases 'Remember, that time is money ... Remember that money begets money.'7 Clock time, the created time to human design, was a precondition for this change in value and practice and formed the perfect partner to abstract, decontextualized money. From the Middle Ages, trade fairs existed where the trade in time became commonplace and calculations about future prices an integral part of commerce. In addition, internatio�al trade by sea required complex calculations about pote�ual profit and loss over long periods, given that trade ships might be away for as long as three years at a time. The time economy of interest and credit, moreover, fed directly into the monetary value of labour time, that is, paid employme�t as an integral part of the production of goo?s and serv_1ce�. However it was not until the French Revolunon that the md1-vidual (�eaning male) ownership of time became enshrined as a legal right

Historical, religious, economic, and political aspects of how time became a commodity that could be allocated, sold, traded, borrowed against or controlled.

Benjamin Franklin metaphor: "time is money ... money begets money"

The task for social theory, therefore, is to render the invisible visible, show relations and interconnections, begin tbe process of questioning the unquestioned. Before we can identify some of these economic relations of temporal inequity, however, we first need to understand in what way the sin of usury was a barrier to the development of economic life as we know it today in industrial societies.

Citing Weber (integrated with Marx), Adam describes how time is used to promote social inequity.

Taken for granted in a socio-economic system, time renders power relationships as invisible

Marx's principal point regarding the commodification of time was that an empty, abstract, quantifiable time that was applicable anywhere, any time was a precondition for its use as an abstract exchange value on the one hand and for the commodification of labour and nature on the other. Only on the basis of this neutral measure could time take such a pivotal position in all economic exchange.

Citing Marx' critique on how time is commodified for value, labor and natural resources.

Clock time, the human creation, as I have shown, operates according to fundamentally different principles from rhe ones ��derpinning the times of tbe cosmos, �ature and the spmt�al realm of eternity. It is a decontextuahzed empty ume that nes the measurement of motion to expression by number. Not change, creativity and process, but static states are given a number value in the temporal frames of calendars and clocks. The artifice rather than the processes of cosmos, nature and spirit, we need to appreciate, came to be the object of trade, control and colonization.

Primer on how clock-time differs from natural world and spiritual expressions of time.

Clock-time as a socio-economic numerical representation is a guiding force for how power is wielded through colonialization/conquered lands and people, labor becomes a value-laden commodity, and

This is so because all cultures, ancient and modern, have established collective ways of relating to the past and future, of synchronizing their activities, of coming to terms with finitude. How we extend ourselves into the past and future, how we pursue immortality and how we temporally manage, organize and regulate our social affairs, however, has been culturally, historically and contextually distinct. Each htstorical epoch with its new forms of socioeconomic expression is simultaneously restructuring its social relations of time.

Sociotemporal reactions/responses/concepts have deep historical roots and intercultural relationships.

Current ways of thinking about time continue to be significantly influenced by post-industrial socio-economic constructs, like clock-time, labor efficiencies (speed), and value metaphors (money, attention, thrift).

the Reformation had a major role to play in the metamorphosis of time from God's gift to commodified, comp�essed, colonized and controlled resource. These four Cs of mdustrial time -comrnodification, compression, colonization and control -will be the focus in these pages, the fifth C of the creation of clock time having been discussed already in the previous chapter. I show their interdependence and id�ntify some of the socio-environmental impacts of those parttcular temporal relations.

Five C's of industrial time: Commodification, compression, colonialization, control, and clock time.

Furthermore, and differentiating digital time from clock time, he suggests that a lack of adherence to chronological time is compounded by the fact that digital technologies connect with a flow of information that is al-ways and instantly available. He argues that continual change, which is bound up with web services such as social network sites, blogs and the news, is central to the experi-enced need for constant connectivity.

Q: How does this idea of time vs information flow affect the data harvested during a digital crowdwork process in humanitarian emergencies?

Q: How does this idea of time vs information flow manifest when the information flow is not chronological due to content throttling or algorithmic decisions on what content to deliver to a user?

For example, in his classic analysis of the his-tory of the machine, Lewis Mumford [30] notes that, “Abstract time became the new medium of existence. Or-ganic functions themselves were regulated by it: one ate, not upon feeling hungry, but when prompted by the clock: one slept, not when one was tired, but when the clock sanc-tioned it.” [p. 17]

Examples of sociotemporality vs clock time by Mumford.

Eat when hungry not at Noon Sleep when tired not at prescribed time

For them, clock time is best understood as sets of practices, which are bound up with time-reckoning and time-keeping technologies, butwhich vary and are shaped by different times, places and communities. This view of clock time is quite different to that often de-picted in the literature, where it is positioned as abstract and mechanistic.

Alternative clock time definition by Glennie and Thrift.

We then detail a position outlined by Glennie and Thrift [12], in which clock time is described as a series of practices rather than a concept created by new timekeep-ing technologies.

Loop up Glennie and Thrift paper.

Need as many examples as I can get that offer concrete ways to describe sociotemporality beyond clock time. This lack of explicit examples seems to trip people up the most. Sociotemporality is still too intangible.

In 2008, Stephen Hawking, the renowned physicist who wrote A Brief History of Time, presided over the unveiling of a clockmaker’s monument to time. The Corpus Clock, created by the inventor and horologist John C. Taylor, does not look like a clock. Its shiny gold disk features 60 notches that radiate from its center. Lights race around the edges of the disc, and a spherical pendulum swings slowly beneath it.

This clock is so strange--you won't be able to stop staring at it...

[Clock strikes.] BRUTUS. Peace! count the clock. CASSIUS. The clock hath stricken three.

Whether intentional or not, the clock is an example of an anachronism. This technique is the inclusion of something that appears to be in the wrong time, used as a device or simply a literary mistake.

Cassius claims that "the clock hath stricken three", signifying the end of the conspirators' meeting about the upcoming assassination. In the Roman era, mechanical clocks were not invented, and the time was told by much more primitive methods.

This anachronism may have been included as subtle humour, or is more symbolic; it may possibly reference the impending 'strike' on Caesar's reign. Furthermore, the motion of the clock is more dramatic than telling time with a sundial etc.

Shakespeare's use of anachronisms throughout Julius Caesar is most likely intentional, but nevertheless it enhances the drama of the conspirator's conversation.

A bar, cafe, museum, and the home of The Long Now Foundation

This is where we had drinks the other night!