https://collections.library.cornell.edu/moa_new/browse.html Cornell University's Making of America Collection<br /> List of Late 1800s-early 1900s magazines and journals in America with links to resources on Hathi Trust repositories

- Jan 2026

-

collections.library.cornell.edu collections.library.cornell.edu

- Jul 2025

-

zenodo.org zenodo.org

-

Philip, Rey (Editor)1 Show affiliations 1. Theory of Ontological Consciousness Project Description This interdisciplinary essay explores a forgotten hypothesis at the intersection of physics, philosophy, and fiction: that consciousness is not a byproduct of matter, but its ontological foundation. Tracing this idea from Heraclitus and Plato to Schrödinger and Penrose, the article integrates metaphysical traditions with quantum models and critiques of materialist reductionism. It introduces the Theory of Ontological Consciousness (TOC) — a literary-philosophical framework proposing ψ̂–Φ interactions as the generative basis of spacetime and form. The essay also reinterprets empirical anomalies, such as those documented by the Global Consciousness Project, as potential signatures of an underlying field of universal consciousness. For more on the Theory of Ontological Consciousness, visit www.toc-reality.org and follow new updates via Medium - https://medium.com/@philiprey.org

Philip, Rey (Editor)1 Description This interdisciplinary essay explores a forgotten hypothesis at the intersection of physics, philosophy, and fiction: that consciousness is not a byproduct of matter, but its ontological foundation. Tracing this idea from Heraclitus and Plato to Schrödinger and Penrose, the article integrates metaphysical traditions with quantum models and critiques of materialist reductionism. It introduces the Theory of Ontological Consciousness (TOC) — a literary-philosophical framework proposing ψ̂–Φ interactions as the generative basis of spacetime and form. The essay also reinterprets empirical anomalies, such as those documented by the Global Consciousness Project, as potential signatures of an underlying field of universal consciousness. For more on the Theory of Ontological Consciousness, visit www.toc-reality.org and follow new updates via Medium - https://medium.com/@philiprey.org

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Apr 2025

-

Local file Local file

-

Such a fine edition and translation deserves (perhaps in a secondedition) a better packaging.

The majority of Scheil's critiques of desired material seems to have been filled in broadly by:

Henley, Georgia, and Joshua Byron Smith, eds. A Companion to Geoffrey of Monmouth. Brill’s Companions to European History 22. Brill, 2020. http://archive.org/details/oapen-20.500.12657-42537.

Obviously this isn't an inconsequential amount of scholarship (575+ pp) to have included in Reeve's volume.

While it's nice to identify what is not in the reviewed volume, it's probably better to frame it that way rather than to seemingly blame the authors/editors for not having included such a massive amount of work. This sort of poor framing is too often seen in the academic literature. Reporting on results and work and putting it out is much more valuable in the short and long term than worrying so much about what is not there. Authors should certainly self-identify open questions for their readers and create avenues to follow them up, but they don't need to be all things to all people.

-

- Mar 2025

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

we would sit in a 1:14 seminar room and take this thing that 1:15 was embodied unique and implicit and 1:18 turn it into something disembodied 1:20 generalized and explicit and therefore 1:23 destroy it

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iEfKPYTOAaY

Discussing and overanalyzing literature can destroy it's beauty and purpose.

-

- Oct 2023

-

Local file Local file

-

Work in a range of fields seems tobe converging in its investigation of the ways in which subjects areproduced by unwarranted if inevitable positings of unity' andidentity,

Literary fields of study converge on subject study

-

we findsomething like a common mechanism.

In every literary theorist structure there is a common conflict in the identification of a subject

"common mechanism"

-

- Sep 2023

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

writing.bobdoto.computer writing.bobdoto.computer

-

Doto, Bob. “Inspired Destruction: How a Zettelkasten Explodes Thoughts (So You Can Have New Ones).” Personal blog. Writing by Bob Doto (blog), September 13, 2023. https://writing.bobdoto.computer/inspired-destruction-how-a-zettelkasten-explodes-thoughts-so-you-can-have-newish-ones/.

-

- Jul 2023

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

Dostoyevsky’s detractors have faulted him for erratic, even sloppy, prose and what Nabokov, the most famous of the un-fans, calls his “gothic rodomontade.”

-

- Jun 2023

-

deadline.com deadline.com

- May 2023

-

www.ala.org www.ala.org

-

Coleridge, Melville, Twain, David Foster Wallace, and a host of others made marginalia into a form of literary expression.

Marginalia is a form of literary expression.

-

- Feb 2023

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

Wolff, Tobias. “Bullet in the Brain.” The New Yorker, September 17, 1995. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1995/09/25/bullet-in-the-brain.

-

- Nov 2022

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.netview1

-

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who’scredited with the first use of the term marginalia, in 1819, coined the term as literarycriticism and to spark public dialogue.6

6 Coleridge, S. T. (1819). Character of Sir Thomas Brown as a writer.Blackwood’s Magazine 6(32), 197.

-

- Jul 2022

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

AuthorW.H. Auden demystified both literature and criticismwhen he said, “Here is a verbal contraption. How doesit work?”

Auden himself kept a commomplace book of his own notes which was published as A Certain World: A Commonplace Book #, so we can read some of his notes! :)

-

- May 2022

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gift_book

Found looking for information about the tradition of birthday books.

-

- Apr 2022

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Every work of art can be read, according to Eco, in three distinct ways: the moral, the allegorical and the anagogical.

Umberto Eco indicates that every work of art can be read in one of three ways: - moral, - allegorical - anagogical

Compare this to early Christianities which had various different readings of the scriptures.

Relate this also to the idea of Heraclitus and the not stepping into the same river twice as a viewer can view a work multiple times in different physical and personal contexts which will change their mood and interpretation of the work.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Writing onstructuralism, Barthes (1972b) states that ‘the goal of all structuralistactivity, whether reflexive or poetic, is to reconstruct an “object” insuch a way as to manifest thereby the rules of functioning (the“functions”) of this object’

-

-

-

Genetic criti-cism seeks to reconstruct the creative process of great authors by examining thesuccession of working papers from reading notes to drafts and editorial changes.

-

The study of personal papers was pioneered by a school of literary criticism (“ge-netic criticism”) that focused on famous authors of the nineteenth and twentiethcenturies who often deposited their papers in national libraries.

-

- Feb 2022

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

The hermeneutic circle (German: hermeneutischer Zirkel) describes the process of understanding a text hermeneutically. It refers to the idea that one's understanding of the text as a whole is established by reference to the individual parts and one's understanding of each individual part by reference to the whole. Neither the whole text nor any individual part can be understood without reference to one another, and hence, it is a circle. However, this circular character of interpretation does not make it impossible to interpret a text; rather, it stresses that the meaning of a text must be found within its cultural, historical, and literary context.

The hermeneutic circle is the idea that understanding a text in whole is underpinned by understanding its constituent parts and understanding the individual parts is underpinned by understanding the whole thereby making a circle of understanding. This understanding of a text is going to be heavily influenced by a text's cultural, historical, literary, and other contexts.

-

- Dec 2021

-

themapisnot.com themapisnot.com

-

Not pain, exactly. Recognition; awakening, even. There were places in me no one had touched.

This rides the line between beauty and suffering, combining medical vivisection with spiritual discovery. Love this so much. There's an eerie intimacy to procedures like this.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

blogs.dickinson.edu blogs.dickinson.edu

-

If ever any beauty I did see, Which I desired, and got, ’twas but a dream of thee.

It's a clever reworking of Plato's cave allegory.

It's a clever reworking of Plato's cave allegory.The lover is presented as the Ideal of Beauty, which all earthly beauty is but an imperfect reflection of it. The previous mistresses that the speaker had a relationship with were mere fantasy(dream) of the lady that he is now in love with. It's a quite common conceit in Renaissance lyrics. However, the expression 'desired and got' is an original line of John Donne to refresh this overused cliché.

Source:

- Nassaar S., Plato in John Donne's 'The Good Morrow' (2003)

- Book: John Donne, The Complete English Poet (1971)

- https://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/cave.htm

-

little room

Donne is envisioning a small area as equivalent to a more enormous space. It's an example of microcosm that views human nature or a well balanced natural phenomena as an perfect example for understanding a bigger world and the order of the universe.

-

THE GOOD-MORROW

The Good-Morrow is an aubade, a love poem sung at dawn that greets the morning by recalling the pleasant night spent with the lover and the togetherness they shared while also lamenting as they realize that they should soon be parted.

In The Good-Morrow the greeting aspect of aubade is particularly emphasized, celebrating the astonishing power of love that transcended them from individuals who dwelled on the unsophisticated pleasure to wholesome, perfectly balanced souls that are awakened in a new world.

To read other examples of John Donne's aubade, see The Sunrising.

-

- Aug 2021

-

web.archive.org web.archive.org

-

Reading should never be merely passive and consist in the mere absorption or copying of information. It should be critical and engage the material reflectively, being guided by questions such as "Why is this important?" "How does this fit in?" "Is it true?" "Why is the author saying what she is saying?" etc.

-

- Feb 2021

-

granta.com granta.com

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Jan 2021

-

open.lib.umn.edu open.lib.umn.edu

-

What is the situation?

The authors use of rhetorical questioning allows the audience to actively engage in the material presented and dive deeper into further analyzing how this could relate to a personal experience.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

supports ideas that promote quality journalism, advance media innovation, engage communities and foster the arts

-

- Sep 2020

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Literary allusion is closely related to parody and pastiche, which are also "text-linking" literary devices.[7]

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Dec 2019

-

enlightenmens.lmc.gatech.edu enlightenmens.lmc.gatech.edu

-

Annotation and passage

Fascinating example of x. Wonder what you mean by y.

-

- Aug 2019

-

www.poetryfoundation.org www.poetryfoundation.org

-

chronicle

The first definition of "chronicle" in the Oxford English Dictionary is "A detailed and continuous register of events in order of time; a historical record, esp. one in which the facts are narrated without philosophic treatment, or any attempt at literary style." Though a chronicle is usually without literary style, the sonnet's chronicle is full of beauty, rhyme, and praise. The OED further notes the figurative use of chronicle, which may apply here, too. Shakespeare's Henry IV describes elders as "time's doting chronicles."

-

- Jun 2019

-

gclinton.com gclinton.com

-

David Jauss. Alone With All That Could Happen: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom about the Craft of Fiction. Writer's Digest Books, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1st edition edition, July 2008.

The chapter "Stacking Stones" describes the various techniques and effects that can be created by authors of short story collections. Put simply, Jauss argues that we ought to read story collections as collections, in the order in which they appear. The argument is based on a series of "unifying principles" and "structural techniques" that stitch collections together. The most important two, in my view, are the "liaison" — or, a motif that speaks across stories — and "mimesis" — the interaction in a collection between form and meaning. Jauss holds The Things They Carried as an exemplar of mimesis.

This text is useful in thinking about collections, but it is also useful for teaching new literary readers about how to approach collections. The instinct is to fragment the collection into digestible chunks — i.e. the stories as individual texts — rather than reckon with them en masse.

-

- May 2019

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

— — shire

"This is standard eighteenth- and nineteenth-century practice to create a sense of realism: the author leaves out the name of the country or person, thus pretending it is a real one and that he or she does not wish to intrude upon the privacy of real people" (The Victorian Web).

-

- Sep 2018

-

www.dartmouth.edu www.dartmouth.edu

-

BOOK 12 THE ARGUMENT The Angel Michael continues from the Flood to relate what shall succeed; then, in the mention of Abraham, comes by degrees to explain, who that Seed of the Woman shall be, which was promised Adam and Eve in the Fall; his Incarnation, Death, Resurrection, and Ascention; the state of the Church till his second Coming. Adam greatly satisfied and recomforted by these Relations and Promises descends the Hill with Michael; wakens Eve, who all this while had slept, but with gentle dreams compos'd to quietness of mind and submission. Michael in either hand leads them out of Paradise, the fiery Sword waving behind them, and the Cherubim taking thir Stations to guard the Place. AS one who in his journey bates at Noone, Though bent on speed, so heer the Archangel paus'd Betwixt the world destroy'd and world restor'd, If Adam aught perhaps might interpose; Then with transition sweet new Speech resumes. [ 5 ] Thus thou hast seen one World begin and end; And Man as from a second stock proceed. Much thou hast yet to see, but I perceave Thy mortal sight to faile; objects divine Must needs impaire and wearie human sense: [ 10 ] Henceforth what is to com I will relate, Thou therefore give due audience, and attend. This second sours of Men, while yet but few; And while the dread of judgement past remains Fresh in thir mindes, fearing the Deitie, [ 15 ] With some regard to what is just and right Shall lead thir lives and multiplie apace, Labouring the soile, and reaping plenteous crop, Corn wine and oyle; and from the herd or flock, Oft sacrificing Bullock, Lamb, or Kid, [ 20 ] With large Wine-offerings pour'd, and sacred Feast, Shal spend thir dayes in joy unblam'd, and dwell Long time in peace by Families and Tribes Under paternal rule; till one shall rise Of proud ambitious heart, who not content [ 25 ] With fair equalitie, fraternal state, Will arrogate Dominion undeserv'd Over his brethren, and quite dispossess Concord and law of Nature from the Earth, Hunting (and Men not Beasts shall be his game) [ 30 ] With Warr and hostile snare such as refuse Subjection to his Empire tyrannous: A mightie Hunter thence he shall be styl'd Before the Lord, as in despite of Heav'n, Or from Heav'n claming second Sovrantie; [ 35 ] And from Rebellion shall derive his name, Though of Rebellion others he accuse. Hee with a crew, whom like Ambition joyns With him or under him to tyrannize, Marching from Eden towards the West, shall finde [ 40 ] The Plain, wherein a black bituminous gurge Boiles out from under ground, the mouth of Hell; Of Brick, and of that stuff they cast to build A Citie and Towre, whose top may reach to Heav'n; And get themselves a name, least far disperst [ 45 ] In foraign Lands thir memorie be lost, Regardless whether good or evil fame. But God who oft descends to visit men Unseen, and through thir habitations walks To mark thir doings, them beholding soon, [ 50 ] Comes down to see thir Citie, ere the Tower Obstruct Heav'n Towrs, and in derision sets Upon thir Tongues a various Spirit to rase Quite out thir Native Language, and instead To sow a jangling noise of words unknown: [ 55 ] Forthwith a hideous gabble rises loud Among the Builders; each to other calls Not understood, till hoarse, and all in rage, As mockt they storm; great laughter was in Heav'n And looking down, to see the hubbub strange [ 60 ] And hear the din; thus was the building left Ridiculous, and the work Confusion nam'd. Whereto thus Adam fatherly displeas'd. O execrable Son so to aspire Above his Brethren, to himself assuming [ 65 ] Authoritie usurpt, from God not giv'n: He gave us onely over Beast, Fish, Fowl Dominion absolute; that right we hold By his donation; but Man over men He made not Lord; such title to himself [ 70 ] Reserving, human left from human free. But this Usurper his encroachment proud Stayes not on Man; to God his Tower intends Siege and defiance: Wretched man! what food Will he convey up thither to sustain [ 75 ] Himself and his rash Armie, where thin Aire Above the Clouds will pine his entrails gross, And famish him of Breath, if not of Bread? To whom thus Michael. Justly thou abhorr'st That Son, who on the quiet state of men [ 80 ] Such trouble brought, affecting to subdue Rational Libertie; yet know withall, Since thy original lapse, true Libertie Is lost, which alwayes with right Reason dwells Twinn'd, and from her hath no dividual being: [ 85 ] Reason in man obscur'd, or not obeyd, Immediately inordinate desires And upstart Passions catch the Government From Reason, and to servitude reduce Man till then free. Therefore since hee permits [ 90 ] Within himself unworthie Powers to reign Over free Reason, God in Judgement just Subjects him from without to violent Lords; Who oft as undeservedly enthrall

Book XII: continues Michael's vision. Adam and Eve are comforted by hearing of the future redemption of their race. The poem ends as they wander forth out of Paradise and the door closes behind them.

-

- Jul 2018

-

course-computational-literary-analysis.netlify.com course-computational-literary-analysis.netlify.com

-

Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger.

Precisely allocated alliteration! The rhythm of this sentence is so beautiful! The act of 'driven' by vanity corresponds to 'anguish', and derision by the same thing corresponds accordingly to 'anger'. I wonder if there are more of this kind of usage in Joyce's novels.

-

- Apr 2018

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

“that it is usual with young ladies to reject the addresses of the man whom they secretly mean to accept, when he first applies for their favour; and that sometimes the refusal is repeated a second or even a third time.

May be referring to the novel Pamela by Samuel Richardson, which was popular at the time and featured a woman who refuses her suitor multiple times before realizing she is in love and marrying him.

-

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

Fordyce’s Sermons

Sermons to Young Women by James Fordyce. Popular female conduct book published in 1766.

-

- Feb 2018

-

www.english.ufl.edu www.english.ufl.edu

-

Barthesian

References Roland Barthes, a French literary theorist, philosopher, linguist, critic, and semiotician. He often interrogated the structure of great writers with distinctive style, such as Voltaire.

-

- Oct 2017

-

lti.hypothesislabs.com lti.hypothesislabs.com

-

The Romantic concept of literary influence, articulated in its present-dayincarnation by Harold Bloom, must expand to encompass not only the work ofwomen, but also the work of both canonical and extra-canonical writers, if itis to be of any help in assessing Jane Austen’s work as a critical reader, anda critical rewriter. ‘‘

I believe that DH work could be instrumental in accomplishing this vision. Since the literature of this time is in the public domain, it is indeed possible to run tests of influence and similarity on all existing manuscripts.

-

artistic influence

After learning about the concept of measuring literary influence with DH tools, it is difficult for me to read any scholarship on influence without automatically thinking what the "data" would say.

-

- Jul 2017

-

www.swamirara.com www.swamirara.com

- May 2017

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

Scott

Sir Walter Scott [1771-1832], “Scottish novelist, poet, historian, and biographer who is often considered both the inventor and the greatest practitioner of the historical novel.”

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sir-Walter-Scott-1st-Baronet

-

Cowper

William Cowper [1731-1800], “one of the most widely read English poets of his day, whose most characteristic work, as in The Task or the melodious short lyric “The Poplar Trees,” brought a new directness to 18th-century nature poetry.”

-

Thomson

James Thomson [1700-1748], “Scottish poet whose best verse foreshadowed some of the attitudes of the Romantic movement. His poetry also gave expression to the achievements of Newtonian science and to an England reaching toward great political power based on commercial and maritime expansion”

https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Thomson-Scottish-poet-1700-1748

-

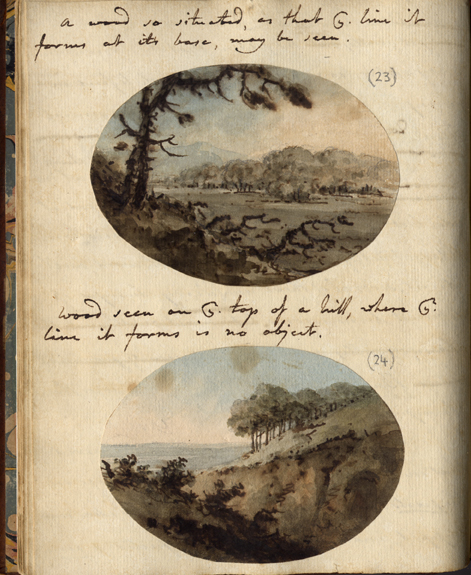

picturesque

"A term expressive of that peculiar kind of beauty, which is agreeable in a picture" (William Gilpin, Essay on Prints, xii). It is a term of the Romantic movement, believed to have been coined by Rev. William Gilpin, which seeks to brings together two paradigms, that of beauty and the sublime, in order to create one aesthetic ideal. The picturesque can be utilized to describe both architecture, such as Sotherton in Mansfield Park, or landscape in the way that Gilpin does in his travel books.

(William Gilpin, From Observations Chiefly Made to Picturesque Beauty)

(William Gilpin, From Observations Chiefly Made to Picturesque Beauty) -

Shakespeare

“William Shakespeare (1564-1616) wrote Hamlet c. 1599-1601. In Austen’s time, Hamlet was a well-known play.”

-

-

blogs.baruch.cuny.edu blogs.baruch.cuny.edu

-

Now one feels blithe as a swimmer calmly borne by celestial waters, and then, as a diver into a secret world, lost in subterranean currents. Arduously sought expressions, hitherto evasive, hidden, will be like stray fishes out of the ocean bottom to emerge on the angler’s hook;

This section of the text has a similarity to Horace Ars Poetica, AP:408- 437, Nature plus training: but see through flattery, Horace says, “Whether a praiseworthy poem is due to nature or art is the question: I’ve never seen the benefit of study lacking a wealth of talent, or of untrained ability: each needs the other’s friendly assistance.” Horace mentions that nature and the hard work of study talent go hand in hand as reflected in his words of “nature,” “study,” “talent” and “untrained.” The same way as Lu chi suggests that inspiration (nature) only comes after the hard work of taming the mind (talent), with his use of words of “celestial” to mean “nature,” “arduously” to mean “study, “anger’s hook” reflects “talent,” and “stray fish” to mean “untrained.” The both realized that you need both nature and talent to be able to release the inner creativity of the writer.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Apr 2017

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

Cowper

William Cowper, (born November 26, 1731, Great Berkhamstead, Hertfordshire, England—died April 25, 1800, East Dereham, Norfolk), one of the most widely read English poets of his day."(https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Cowper). "Marianne, in Sense and Sensibility, complains about the way Edward Ferrars reads Cowper aloud...Cowper's mediative poetry celebrated the beauty of nature. He is often considered an early Romantic poet, and as such would particularly appeal to Marianne"(Patrice Hannon, 101 Things You Didn't Know About Jane Austen: The Truth About the World's Most Intriguing Romantic Literary Heroine, p. 96).

-

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

Columella’s.”

A reference to a 1779 novel, Columella, or The Distressed Anchoret, a colloquial tale by Richard Graves. Susan Allen Ford points out how this rather esoteric reference to literature makes Elinor more alike her mother than previously indicated.

-

-

web.hypothes.is web.hypothes.is

-

University of Oklahoma

Sarah and David Wrobel's project here is so cool: they leveraged the Hypothes.is tag feature to have students explore the "layers" of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath. While the idea of such layers could perhaps be said about any literary text, for Steinbeck there was something explicit about the layers of that particular novel. As he wrote to his editor at the time:

"The Grapes of Wrath" was published, Steinbeck wrote: "There are five layers in this book, a reader will find as many as he can and he won't find more than he has in himself."

-

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

mama

The narrator often switches between the minds of Elinor, and that of Marianne's. The usage of "mama" gives readers a clear knowledge of whose mind we are in - in this case, we are in the younger character (Marianne's) mind. Elinor, the older character, typically refers to her mother as Mrs. Dashwood; much more maturely. This shows the way that ladies carried themselves in this time.

-

- Mar 2017

-

ac.els-cdn.com ac.els-cdn.com

-

the multilayered nature of interaction and language use, in all their complexity and as a network of interdependencies among all the elements in the setting, not only at the social level, but also at the physical and symbolic level

Does this map to literary theory in any way?...

-

- Jan 2017

-

aeon.co aeon.co

-

The so-called ‘cultural’ turn in literary studies since the 1970s, with its debt to postmodern understandings of the relationship between power and narrative, has pushed the field away from such systematic, semi-mechanistic ways of analysing texts. AI remains concerned with formal patterns, but can nonetheless illuminate key aspects of narrative, including time, space, characters and plot.

-

- Oct 2016

-

ebooks.adelaide.edu.au ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

-

A stout wave-walker he bade make ready.

kenning

-

- Sep 2016

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

pulp fiction

I understand that literary fiction is more writerly while pulp fiction is more readerly... But is it really that clean cut between the two? Is it possible for a work considered pulp fiction to have at least some qualities of a writerly work, or is the classification of fiction works a binary system?

-

-

ebooks.adelaide.edu.au ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

-

war-attire

Kenning for armor

-

-

ebooks.adelaide.edu.au ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

-

hall-thane’s

Kenning

-

Wielder-of-Wonder. — Woe for that man

assonance

-

-

ebooks.adelaide.edu.au ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

-

mailed coat

kenning

-

ever he envied that other men

assonance

-

-

ebooks.adelaide.edu.au ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

-

Famed was this Beowulf: 1 far flew the boast of him

Alliteration

-

-

ebooks.adelaide.edu.au ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

-

boards of the benches blood-besprinkled

Alliteration

-

- Jun 2016

-

Local file Local file

-

Whilecriticaltheoristsmayquestionthe“prestigeofauthorship”and“allmanifes-tationsofauthor-ity”(Birkerts,1994,pp.158–159)—whichhelpsexplainthepredilectionforpostmodernistandeschatologicaltitlessuchasTheDeathoftheAuthor(Bar-thes,1977),WhatisanAuthor?(Foucault,1977),andTheDeathofLiterature(Kernan,1990)—thereislittledoubtthatboththesymbolicandmaterialconsequencesofauthor

Critical theorists may question the "prestige of authorship," but there is little doubt that the material consequences are more far reaching than they were in ancient times.

Actually, this is a misreading of Foucault, who discusses the economic implications of authorship.

-

-

-

No Bias, No Merit: The Case against Blind Submission

Fish, Stanley. 1988. “Guest Column: No Bias, No Merit: The Case against Blind Submission.” PMLA 103 (5): 739–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/462513.

An interesting essay in the context I'm reading it (alongside Foucault's What is an author in preparation for a discussion of scientific authorship.

Among the interesting things about it are the way it encapsulates a distinction between the humanities and sciences in method (though Fish doesn't see it and it comes back to bite him in the Sokol affair). What Frye thinks is important because he is an author-function in Foucault's terms, I.e. a discourse initiator to whom we return for new insight.

Fish cites Peters and Ceci 1982 on peer review, and sides with those who argue that ethos should count in review of science as well.

Also interesting for an illustration of how much the field changed, from new criticism in the 1970s (when the first draft was written) until "now" i.e. 1989 when political criticism is the norm.

-

But perhaps the greatest change is the one that renders the key opposition of the essay-between the timeless realm of literature and the pressures and exigencies of politics-inaccurate as a description of the assumptions prevailing in the profession. There are of course those who still believe that literature is defined by its independence of social and political contexts (a "concrete universal" in Wimsatt's terms), but today the most influential and up-to-date voices are those that proclaim exactly the reverse and ar- gue that the thesis of literary autonomy is itself a political one, part and parcel of an effort by the con- servative forces in society to protect traditional values from oppositional discourse. Rather than reflecting, as Ransom would have it, an "order of existence" purer than that which one finds in "actual life," lit- erature in this new (historicist) vision directly and vigorously "participates in historical processes and in the political management of reality" (Howard 25). Moreover, as Louis Montrose observes, if litera- ture is reconceived as a social rather than a merely aesthetic practice, literary criticism, in order to be true to its object, must be rearticulated as a social practice too and no longer be regarded as a merely academic or professional exercise (11-12

How much literary criticism changed between 1979, 1982, and 1988! From ontological wholes to politicised

-

Everyone is aware of that risk, although it is usually not acknowledged with the explicitness that one finds in the opening sentence of Raymond Waddington's essay on books 11 and 12 of Paradise Lost. "Few of us today," Waddington writes, "could risk echoing C. S. Lewis's condemnation of the concluding books of Paradise Lost as an 'untransmuted lump of futurity"' (9). The nature of the risk that Wad- dington is about not to take is made clear in the very next sentence, where we learn that a generation of critics has been busily demonstrating the subtlety and complexity of these books and establishing the fact that they are the product of a controlled poetic design. What this means is that the kind of thing that one can now say about them is constrained in advance, for, given the present state of the art, the critic who is concerned with maintaining his or her professional credentials is obliged to say something that makes them better. Indeed, the safest thing the critic can say (and Waddington proceeds in this es- say to say it) is that, while there is now a general recognition of the excellence of these books, it is still the case that they are faulted for some deficiency that is in fact, if properly understood, a virtue. Of course, this rule (actually a rule of thumb) does not hold across the board. When Waddington observes that "few of us today could risk," he is acknowledging, ever so obliquely, that there are some of us who could. Who are they, and how did they achieve their special status? Well, obviously C. S. Lewis was once one (although it may not have been a risk for him, and if it wasn't why wasn't it?), and if he had not already died in 1972, when Waddington was writing, presumably he could have been one again. That is, Lewis's status as an authority on Renaissance literature was such that he could offer readings with- out courting the risk facing others who might go against the professional grain, the risk of not being listened to, of remaining unpublished, of being unattended to, the risk of producing something that was by definition-a definition derived from prevailing institutional conditions-without me

on the necessity of discovering virtue in literary work as a professional convention of our discipline.

This is a really interesting and useful passage for my first year lectures

-

-

screen.oxfordjournals.org screen.oxfordjournals.org

-

verningthis function is the belief that there must be - at a particular levelof an author's thought, of his conscious or unconscious desire — apoint where contradictions are resolved, where the incompatibleelements can be shown to relate to one another or to cohere arounda fundamental and originating contradiction. Fin

This is not true (in theory) of scientific authorship. We don't judge the coherence of the oeuvre.

Again it conflict with Fish's view of literary criticism

-

In literary criticism, for example, the traditional methods fordefining an author - or, rather, for determining the configurationof the author from existing texts - derive in large part from thoseused in the Christian tradition to authenticate (or to reject) theparticular texts in its possession. Modern criticism, in its desireto 'recover' the author from a work, employs devices stronglyreminiscent of Christian exegesis w

Relationship of literary criticism to exegesis

-

At the same time, however, 'literary' discourse was acceptableonly if it carried an author's name; every text of poetry or fictionwas obliged to state its author and the date, place and circumstanceof its writing. The meaning and value attributed to the text de-pended on this information. If by accident or design a text waspresented anonymously, every effort was made to locate its author.Literary anonymity was of interest only as a puzzle to be solved as,in our day, literary works are totally dominated by the sovereigntyof the author. (

At the same time scientific authorship was becoming anonymous, literary authorship was no longer accepted as anonymous (this is something Chartier disagrees with emphatically)

-

nsequently, we cansay that in our culture, the name of an author is a variable thataccompanies only certain texts to the exclusion of others: a privateletter may have a signatory, but it does not have an author; acontract can have an underwriter, but not an author; and, similarlyan anonymous poster attached to a wall may have a writer, buthe cannot be an author. In this sense, the function of an author isto characterize the existence, circulation, and operation of certaindiscourses within a society

Very useful statement of where foucault applies in this case: to literary discussion, not advertising, not letters, and so on.

Science would fall into the "not this" category, I suspect.

-

We can conclude that, unlike a proper name, which moves fromthe interior of a discourse to the real person outside who producedit, the name of the author remains at the contours of texts -separating one from the other, defining their form, and character-izing their mode of existence. It points to the existence of certaingroups of discourse and refers to the status of this discourse withina society and culture. The author's name is not a function of aman's civil status, nor is it fictional; it is situated in the breach,among the discontinuities, which gives rise to new groups of dis-course and their singular mode of existence. C

Again, an "Implied Author" type idea that is completely not relevant to science--although ironically, the H-index tries to make it relevant. In science, the author name is not the function that defines the text; it is the person to whom the credit it to be given rather than a definition of Oeuvre. This is really useful distinction for discussing what is different between the two discourses.

-

-

www.ubu.com www.ubu.com

-

Who is speaking in this way? Is it the story's hero, concerned to ignore the castrato concealed beneath the woman? Is it the man Balzac, endowed by his personal experience with a philosophy of Woman? Is it the author Balzac, professing certain "literary" ideas of femininity? Is it universal wisdom? or romantic psychology? It will always be impossible to know, for the good reason that all writing is itself this special voice, consisting of several indiscernible voices, and that literature is precisely the invention of this voice, to which we cannot assign a specific origin: literature is that neuter, that composite, that oblique into which every subject escapes, the trap where all identity is lost, beginning with the very identity of the body that writes.

Why science authorship is not the same as poetic authorship: the lack of identity of the author. cf. Booth 1961, Rhetoric of Fiction

-

- May 2016

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

midnight assassins

A reference to The Italian, or the Confessional of the Black Penitents, by Anne Radcliffe, published 1797. In particular, this is the title chosen for a popular pirated chapbook version of the novel, popular because of its cheap production and therefore low price (British Library).

-

poison nor sleeping potions

Allusion to The Castle of Otranto by Sir Henry Walpole (1764). Complicated by the fact that the "poison" and the sleeping potion were one and the same, and the sleeping potion was only used to give the the appearance of death (Montague Summers, The Gothic Quest- A History of the Gothic Novel).

-

Montoni

Here, Catherine brings up Montoni, a character from from Ann Radcliffe's gothic novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho (Rachel Knowles, "The Mysteries of Udolpho" by Ann Radcliffe).

-

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

Udolpho

"The Mysteries of Udolpho is a Gothic novel by Ann Radcliffe, published in 1794. It was one of the most popular novels of the late 18th and early 19th centuries... The Mysteries of Udolpho is set in France and Italy in the late 16th century. The main character is Emily St. Aubert, a beautiful and virtuous young woman. When her father dies, the orphaned Emily goes to live with her aunt. Her aunt’s husband, an Italian nobleman called Montoni, tries to force Emily to marry his friend. Montoni is a typical Gothic villain. He is violent and cruel to his wife and Emily, and locks them in his castle. Eventually Emily escapes, and the novel ends happily with Emily’s marriage to the man she loves" (British Library).

-

Horrid Mysteries

Isabella is referencing The Horrid Mysteries, A Story from the German of the Marquis of Grosse, a translation by Peter Will of Der Genius. The original is a German Gothic novel by Carl Grosse published in 1796 by Minerva Press (wiki, Horrid Mysteries).

The story's plot synopsis is as follows: "The hero of the tale, the Marquis of Grosse, finds himself embroiled in a secret revolutionary society which advocates murder and mayhem in pursuit of an early form of communism. He creates a rival society to combat them and finds himself hopelessly trapped between the two antagonistic forces. The book has been both praised and lambasted for its lurid portrayal of sex, violence and barbarism" (wiki, Horrid Mysteries).

-

The dreadful black veil!

“Emily [the main character of Radcliffe’s Udolpho] has heard rumors of ghosts and mysterious tales about the Castle. She goes into a room and finds something hidden beneath a black veil. What she sees is so frightful that she will not go near the room again. There is a rumour that the Count was married to the former owner of the Castle, Signora Laurentini di Udolpho, and Emily believes that he has killed her and it is her body that lies under the black veil… Clearly not the body of Signora Laurentini di Udolpho as Emily thought, as she turned out to be Sister Agnes. What Emily saw behind the veil was a human figure, partly decayed, but the figure was not real but made of wax. It had been made as a rather gruesome penance for the Marquis of Udolpho, that he should look upon it for a certain time each day in order to receive pardon for his sins” (Knowles).

“Emily [the main character of Radcliffe’s Udolpho] has heard rumors of ghosts and mysterious tales about the Castle. She goes into a room and finds something hidden beneath a black veil. What she sees is so frightful that she will not go near the room again. There is a rumour that the Count was married to the former owner of the Castle, Signora Laurentini di Udolpho, and Emily believes that he has killed her and it is her body that lies under the black veil… Clearly not the body of Signora Laurentini di Udolpho as Emily thought, as she turned out to be Sister Agnes. What Emily saw behind the veil was a human figure, partly decayed, but the figure was not real but made of wax. It had been made as a rather gruesome penance for the Marquis of Udolpho, that he should look upon it for a certain time each day in order to receive pardon for his sins” (Knowles). -

Camilla

This is the third novel by Frances "Fanny" Burney, originally published in 1796 (LibriVox).

"This is the story of Camilla, her beloved but selfish brother Lionel, her sisters Eugenia and Lavinia, and their extremely beautiful but thoughtless cousin Indiana on the months proceeding their marriages. Camilla is deeply in love with Edgar and he loves her back. However, on the advice of a friend, decides to make sure that she is free of fault. She has the luck to find herself in lot of uncomplimentary and comic situations which doesn't make Edgar's wish easy. Meanwhile, Camilla, on the advice of her father, is trying to make sure that Edgar really loves her before marrying him" (LibriVox).

-

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

The Mirror

The Mirror was a periodical started by Scottish novelist Henry Mackenzie’s essay-reading society in Edinburgh, Scotland. Mackenzie, the editor and primary contributor, began publication of The Mirror in January 1779, and continued to edit the paper until May 1780 (Henry Morley, ed., “Editor’s Introduction” in Henry Mackenzie, The Man of Feeling, 1886).

-

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

I shall soon leave you as far behind me as — what shall I say? — I want an appropriate simile. — as far as your friend Emily herself left poor Valancourt when she went with her aunt into Italy.

The names Emily and Valancourt are reference to characters from the gothic romance novel Mysteries of Udolpho by Mrs. Ann Radcliffe, which was published in 1794. Emily is the heroine of the novel who goes through misfortunes after the death of her father. Valancourt is a traveller who Emily falls in love with while traveling with her father. After her father's death, Emily is under the guardianship of her aunt Madame Cheron who tries to keep Valancourt and Emily from being together and eventually marrying each other. Madame Cheron goes as far as to take Emily away with her to Italy to be rid of Valancourt. Valancourt asks Emily to marry him in secret, but Emily refuses and leaves him to go with her aunt to Italy. (Regency History)

Here is a novel cover of Anne Radcliffe's Mysteries of Udolpho:

-

- Apr 2016

-

annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net annotatingausten.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

Yet he had not mentioned that his stay would be so short!

This is an example of a style of writing that Jane Austen was known to perfect through her writing and which she is quite famous for called free indirect discourse. This is when the narrator slips into the mind of the character momentarily and reveals thoughts that a third person narrator would have never been privileged to, but without using third person pronouns like "he" or "she."

-

- Jan 2016

-

dlsanthology.commons.mla.org dlsanthology.commons.mla.org

-

Meanwhile, in almost exactly the same decades that the Internet arose and eventually evolved social computing, literary scholarship followed similar principles of decentralization to evolve cultural criticism.7

Wow. This is the most interesting statement that I've read in a while. Wish I could pin an annotation...

Really helps me justify my career arc, turning from literary criticism as a career to software "development."

-

- Dec 2015

-

cityheiress.sfsuenglishdh.net cityheiress.sfsuenglishdh.netACT III2

-

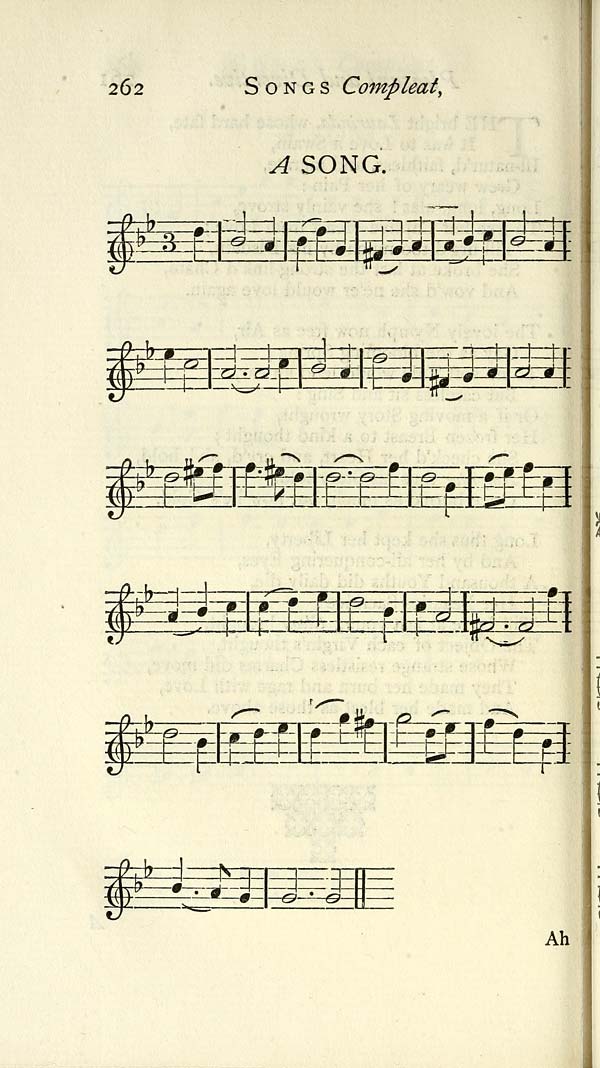

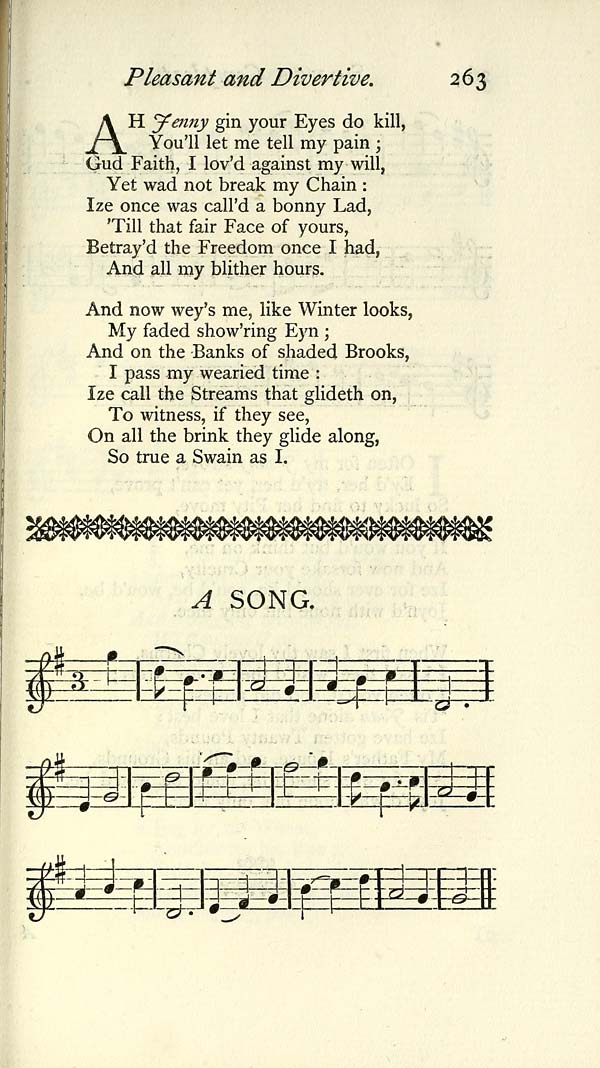

SONG Ah, Jenny, gen your Eyes do kill, You’ll let me tell my Pain; Gued Faith, I lov’d against my Will, But wad not break my Chain. I ence was call’d a bonny Lad, Till that fair Face of yours Betray’d the Freedom ence I had, And ad my bleether howers. But noo ways me like Winter looks, My gloomy showering Eyne, And on the Banks of shaded Brooks I pass my wearied time. I call the Stream that gleedeth on, To witness if it see, On all the flowry Brink along, A Swain so true as Iee.

This two verse song by Aphra Behn would have been considered a "Scotch Jig". It was set to the tune of "Ah, Jenny Gin" (Ebsworth).

Sheet music published between 1719-20.

-

Absalom and Achitophel

“Absalom and Achitophel” was a highly anti-Catholic satirical poem written by John Dryder in 1681. The allusion is brought up as Wilding sets to find out what Sir Timothy thinks about him. References this poem, he jabs at Wilding’s character as if he’d have nothing to do with the writing of such a work he’d regard as great.<br> ( Encyclopædia Britannica) http://www.britannica.com/topic/Absalom-and-Achitophel

-

-

cityheiress.sfsuenglishdh.net cityheiress.sfsuenglishdh.net

-

Then let the strucken Deer go weep

The slightly misquoted first line of Hamlet's speech at Act 3, scene ii, ll. 256-59:

Why, let the stricken deer go weep, The hart ungallèd play. For some must watch while some must sleep. So runs the world away.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Oct 2015

-

www.newrepublic.com www.newrepublic.com

-

No joke is funny unless you see the point of it, and sometimes a point has to be explained.

Sounds logical, in the abstract. But the explanation is often known to “kill the joke”, to decrease the humour potential. In some cases, it transforms the explainee into the butt of a new joke. Something similar has been said about hermeneutics and æsthetics. The explanation itself may be a new form of art, but it runs the risk of first destroying the original creation.

-

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

She was one of the few remaining legends of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, when a new crop of writers from Latin America announced themselves to the world, with her help, and changed Spanish-language publishing forever.

Carmen Balcells was at the center of the Latin American literary boom, which popularized the works of Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, Julio Cortázar, and many other writers who had been censored or neglected by publishing houses in their own countries.

-

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

heavenly Helen

alliteration

-

blest

irony again

-

heavenly

The word "heavenly" is ironic, given the origin of Faustus's powers.

-

- Feb 2014

-

blogs.law.harvard.edu blogs.law.harvard.edu

-

Alexander v. Haley, 460 F.Supp. 40 (S.D.N.Y. 1978)

-