https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/manuskripte/manuskript/MS_2906_0001<br /> https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/manuskripte/manuskript/MS_2906_0004

Luhmann wrote his own zettelkasten method one pager back on Münster, January 13, 1968

https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/manuskripte/manuskript/MS_2906_0001<br /> https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/manuskripte/manuskript/MS_2906_0004

Luhmann wrote his own zettelkasten method one pager back on Münster, January 13, 1968

chatgpt, write me a summary of the zettelkasten method that is documented extensively online so i can post it to a sub full of people who have almost certainly heard of it before, but don't use the actual term

by u/andrewlonghofer at https://www.reddit.com/r/ObsidianMD/comments/1mbs3rd/technique_of_the_card_index_box_by_niklas_luhmann/

This is hilarious given that the article he's commenting on is a document written by Luhmann in 1968!

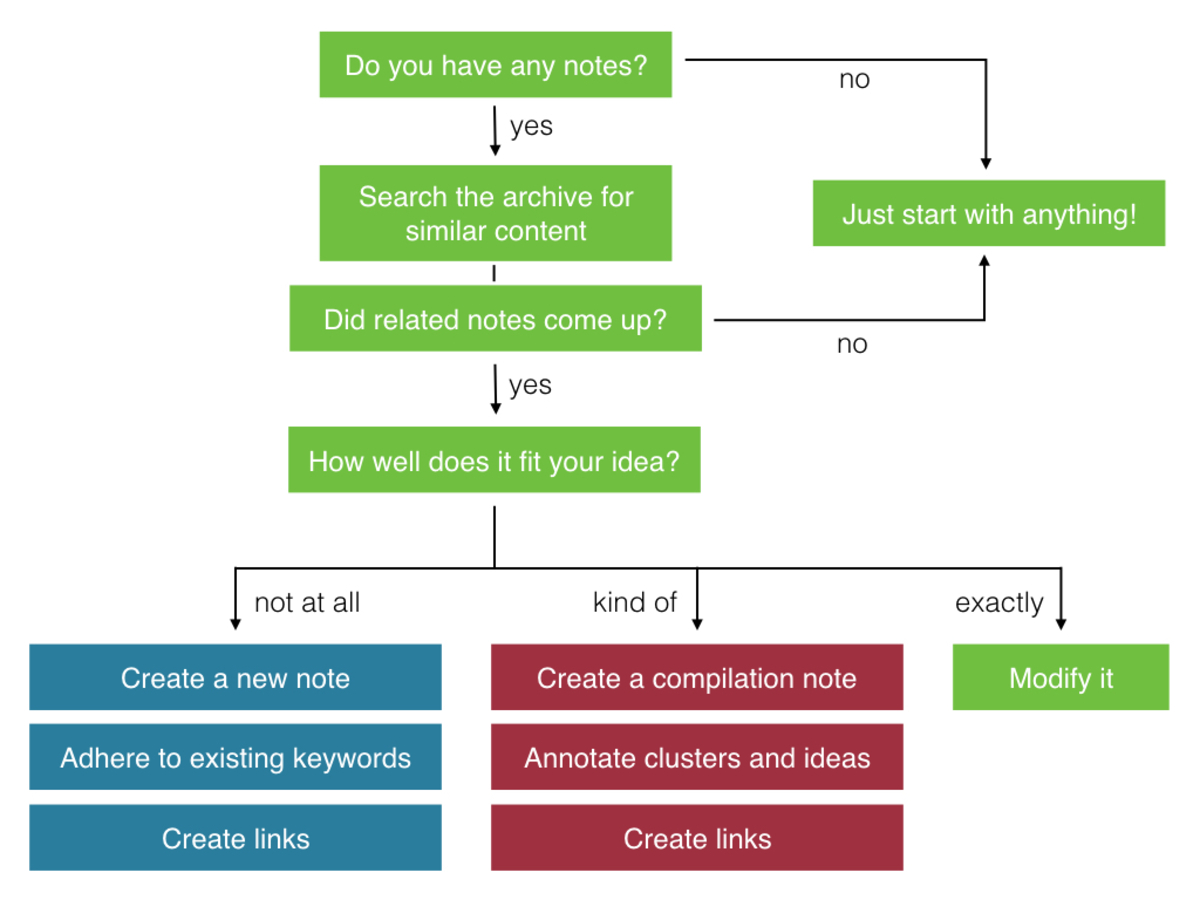

How to Start a Zettelkasten When You Are Stuck in Theory • Zettelkasten Method<br /> by [[sascha]]<br /> accessed on 2025-12-11T14:08:33

Meh...

one of the shortest routes, but it also presumes a knowledge of too much other theory and is geared at getting one moving at creating rather than reading the theory

Niklas Luhmann's Original Zettelkasten: Two Slip Boxes, Fixed Numbering, and Communication Partner<br /> by [[Ernest Chiang]]<br /> accessed on 2025-12-05T20:55:42

Introduction to Luhmann's Zettelkasten by [[Yann Herklotz]]

Value of knowledge in a zettelkasten as a function of reference(use/look up) frequency; links to other ideas; ease of recall without needing to look up (also a measure of usefulness); others?

Define terms and create a mathematical equation of stocks and flows around this system of information. Maybe "knowledge complexity" or "information optimization"? see: https://hypothes.is/a/zejn0oscEe-zsjMPhgjL_Q

takes into account the value of information from the perspective of a particular observer<br /> relative information value

cross-reference: Umberto Eco on no piece of information is superior: https://hypothes.is/a/jqug2tNlEeyg2JfEczmepw

Inspired by idea in https://hypothes.is/a/CdoMUJCYEe-VlxtqIFX4qA

Here's my setup: Literature Notes go in the literature folder. Daily Notes serve as fleeting notes. Project-related Notes are organized in their specific project folders within a larger "Projects" folder.

inspired by, but definitely not take from as not in evidence

Many people have "daily notes" and "project notes" in what they consider to be their zettelkasten workflow. These can be thought of as subcategories of reference notes (aka literature notes, bibliographic notes). The references in these cases are simply different sorts of material than one would traditionally include in this category. Instead of indexing the ideas within a book or journal article, you're indexing what happened to you on a particular day (daily notes) or indexing ideas or progress on a particular project (project notes). Because they're different enough in type and form, you might keep them in their own "departments" (aka folders) within your system just the same way that with enough material one might break out their reference notes to separate books from newspapers, journal articles, or lectures.

In general form and function they're all broadly serving the same functionality and acting as a ratchet and pawl on the information that is being collected. They capture context; they serve as reminder. The fact that some may be used less or referred to less frequently doesn't make them necessarily less important

the ideas we capture, re�ne, connect,and search for in our zettelkasten.

An alternate stating of the process: 1. capture<br /> 2. refine<br /> 3. connect<br /> 4. search

cross-reference earlier process: https://hypothes.is/a/HgcILIvyEe-OfdOArKZxGg

practices related to having and capturing thoughts (chapters 1and 2); re�ning thoughts into clear ideas that can be repurposed (chapter 3);connecting ideas across topics (chapters 4 and 5); developing theseconnections and making them accessible to you (chapter 6); andtransforming all the above into writing for readers—writing that can bereintegrated back into the system (chapters 7, 8 and 9).

Overview of Bob Doto's suggested process:<br /> 1. having and capturing thoughts<br /> 2. refining thoughts into clear ideas that can be repurposed<br /> 3. connecting ideas across topics<br /> 4. developing connections and making them accessible<br /> 5. transforming notes into writing for readers 6. re-integrating writing back into the system (he lumped this in with 5, but I've broken it out)

How do these steps relate to those of others?

Eg: Miles1905: collect, select, arrange, dictate/write (and broadly composition)

"I made a great study of theology at one time," said Mr Brooke, as if to explain the insight just manifested. "I know something of all schools. I knewWilberforce in his best days.6Do you know Wilberforce?"Mr Casaubon said, "No.""Well, Wilberforce was perhaps not enough of a thinker; but if I went intoParliament, as I have been asked to do, I should sit on the independent bench,as Wilberforce did, and work at philanthropy."Mr Casaubon bowed, and observed that it was a wide field."Yes," said Mr Brooke, with an easy smile, "but I have documents. I began along while ago to collect documents. They want arranging, but when a question has struck me, I have written to somebody and got an answer. I have documents at my back. But now, how do you arrange your documents?""In pigeon-holes partly," said Mr Casaubon, with rather a startled air of effort."Ah, pigeon-holes will not do. I have tried pigeon-holes, but everything getsmixed in pigeon-holes: I never know whether a paper is in A or Z.""I wish you would let me sort your papers for you, uncle," said Dorothea. "Iwould letter them all, and then make a list of subjects under each letter."Mr Casaubon gravely smiled approval, and said to Mr Brooke, "You have anexcellent secretary at hand, you perceive.""No, no," said Mr Brooke, shaking his head; "I cannot let young ladies meddle with my documents. Young ladies are too flighty."Dorothea felt hurt. Mr Casaubon would think that her uncle had some special reason for delivering this opinion, whereas the remark lay in his mind aslightly as the broken wing of an insect among all the other fragments there, anda chance current had sent it alighting on her.When the two girls were in the drawing-room alone, Celia said —"How very ugly Mr Casaubon is!""Celia! He is one of the most distinguished-looking men I ever saw. He is remarkably like the portrait of Locke. He has the same deep eye-sockets."

Fascinating that within a section or prose about indexing within MiddleMarch (set in 1829 to 1832 and published in 1871-1872), George Eliot compares a character's distinguished appearance to that of John Locke!

Mr. Brooke asks for advice about arranging notes as he has tried pigeon holes but has the common issue of multiple storage and can't remember under which letter he's filed his particular note. Mr. Casaubon indicates that he uses pigeon-holes.

Dorothea Brooke mentions that she knows how to properly index papers so that they might be searched for and found later. She is likely aware of John Locke's indexing method from 1685 (or in English in 1706) and in the same scene compares Mr. Casaubon's appearance to Locke.

Watched [[The Unenlightened Generalists]] in Linked Notes: An Introduction to the Zettelkasten Method

A 28:30 intro to zettelkasten. I could only make it about 10 minutes in. Fine, but nothing more than yet another "one pager" on method with a modified version of the Luhmann myth as motivation.

turn off the light, and take off his shirt, his shorts, and his underwear.

Mr Collier had a special technique. He cut out the quotations and, dipping a brush in sweet-smelling Perkins Paste glue, he stuck the quotation onto the slip. It was quick, and some nights he could get through 100 slips. Just him and the sound of his scissors, the incessant croak of cicadas, and the greasy smell of the neighbour’s lamb chops hanging in the close air. Around midnight, he would stop work, gather up the scraps of paper, clear the table,

zettelkasten and nudity!!!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CAerQtNkGT0

Short video version

Lovely. I guess what I'm trying to define is some methodology for practicing. Many times I simply resort to my exhaustive method, which has worked for me in the past simply due to brute force.Thank you for taking the time to respond and for what look like some very interesting references.

reply to u/ethanzanemiller at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/185xmuh/comment/kb778dy/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

Some of your methodology will certainly depend on what questions you're asking, how well you know your area already, and where you'd like to go. If you're taking notes as part of learning a new area, they'll be different and you'll treat them differently than notes you're collecting on ideas you're actively building on or intriguing facts you're slowly accumulating. Often you'll have specific questions in mind and you'll do a literature review to see what's happing around that area and then read and take notes as a means of moving yourself closer to answering your particular questions.

Take for example, the frequently asked questions (both here in this forum and by note takers across history): how big is an idea? what is an atomic note? or even something related to the question of how small can a fact be? If this is a topic you're interested in addressing, you'll make note of it as you encounter it in various settings and see that various authors use different words to describe these ideas. Over time, you'll be able to tag them with various phrases and terminologies like "atomic notes", "one idea per card", "note size", or "note lengths". I didn't originally set out to answer these questions specifically, but my interest in the related topics across intellectual history allowed such a question to emerge from my work and my notes.

Once you've got a reasonable collection, you can then begin analyzing what various authors say about the topic. Bring them all to "terms" to ensure that they're talking about the same things and then consider what arguments they're making about the topic and write up your own ideas about what is happening to answer those questions you had. Perhaps a new thesis emerges about the idea? Some have called this process having a conversation with the texts and their authors or as Robert Hutchins called it participating in "The Great Conversation".

Almost anyone in the forum here could expound on what an "atomic note" is for a few minutes, but they're likely to barely scratch the surface beyond their own definition. Based on the notes linked above, I've probably got enough of a collection on the idea of the length of a note that I can explore it better than any other ten people here could. My notes would allow me a lot of leverage and power to create some significant subtlety and nuance on this topic. (And it helps that they're all shared publicly so you can see what I mean a bit more clearly; most peoples' notes are private/hidden, so seeing examples are scant and difficult at best.)

Some of the overall process of having and maintaining a zettelkasten for creating material is hard to physically "see". This is some of the benefit of Victor Margolin's video example of how he wrote his book on the history of design. He includes just enough that one can picture what's happening despite his not showing the deep specifics. I wrote a short piece about how I used my notes about delving into S.D. Goitein's work to write a short article a while back and looking at the article, the footnotes, and links to my original notes may be illustrative for some: https://boffosocko.com/2023/01/14/a-note-about-my-article-on-goitein-with-respect-to-zettelkasten-output-processes/. The exercise is a tedious one (though not as tedious as it was to create and hyperlink everything), but spend some time to click on each link to see the original notes and compare them with the final text. Some of the additional benefit of reading it all is that Goitein also had a zettelkasten which he used in his research and in leaving copies of it behind other researchers still actively use his translations and notes to continue on the conversation he started about the contents of the Cairo Geniza. Seeing some of his example, comparing his own notes/cards and his writings may be additionally illustrative as well, though take care as many of his notes are in multiple languages.

Another potentially useful example is this video interview with Kathleen Coleman from the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae. It's in the realm of historical linguistics and lexicography, but she describes researchers collecting masses of data (from texts, inscriptions, coins, graffiti, etc.) on cards which they can then study and arrange to write their own articles about Latin words and their use across time/history. It's an incredibly simple looking example because they're creating a "dictionary", but the work involved was painstaking historical work to be sure.

Again, when you're done, remember to go back and practice for yourself. Read. Ask questions of the texts and sources you're working with. Write them down. Allow your zettelkasten to become a ratchet for your ideas. New ideas and questions will emerge. Write them down! Follow up on them. Hunt down the answers. Make notes on others' attempts to answer similar questions. Then analyze, compare, and contrast them all to see what you might have to say on the topics. Rinse and repeat.

As a further and final (meta) example, some of my answer to your questions has been based on my own experience, but the majority of it is easy to pull up, because I can pose your questions not to my experience, but to my own zettelkasten and then quickly search and pull up a variety of examples I've collected over time. Of course I have far more experience with my own zettelkasten, so it's easier and quicker for me to query it than for you, but you'll build this facility with your own over time.

Good luck. 🗃️

Taking notes for historical writing .t3_185xmuh._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } questionI'm trying to understand how to adopt parts of the Zettelkasten method for thinking about historical information. I wrote a PhD in history. My note-taking methodology was a complete mess the whole time. I used note-taking to digest a book, but it would take me two or three times longer than just reading. I would go back over each section and write down the pieces that seemed crucial. Sometimes, when I didn't know a subject well, that could take time. In the end, I would sometimes have many pages of notes in sequential order sectioned the way the book was sectioned, essentially an overlay of the book's structure. It was time-consuming, very hard, not useless at all, but inefficient.Now consider the Zettelkasten idea. I haven't read much of Luhmann. I recall he was a sociologist, a theorist in the grand style. So, in other words, they operate at a very abstract level. When I read about the Zettelkasten method, that's the way it reads to me. A system for combining thoughts and ideas. Now, you'll say that's an artificial distinction, perhaps...a fact is still rendered in thought, has atomicity to it etc. And I agree. However, the thing about facts is there are just A LOT of them. Before you write your narrative, you are drowning in facts. The writing of history is the thing that allows you to bring some order and selectivity to them, but you must drown first; otherwise, you have not considered all the possibilities and potentialities in the past that the facts reveal. To bring it back to Zettelkasten, the idea of Zettel is so appealing, but how does it work when dealing with an overwhelming number of facts? It's much easier to imagine creating a Zettelkasten from more rarefied thoughts provoked by reading.So, what can I learn from the Zettelkasten method? How can I apply some or all of its methodologies, practically speaking? What would change about my initial note-taking of a book if I were to apply Zettelkasten ideas and practice? Here is a discussion about using the method for "facts". The most concrete suggestions here suggest building Zettels around facts in some ways -- either a single fact, or groups of facts, etc. But in my experience, engaging with a historical text is a lot messier than that. There are facts, but also the author's rendering of the facts, and there are quotes (all the historical "gossip"), and it's all in there together as the author builds their narrative. You are trying to identify the key facts, the author's particular angle and interpretation, preserve your thoughts and reactions, and save these quotes, the richest part of history, the real evidence. In short, it is hard to imagine being able to isolate clear Zettel topics amid this reading experience.In Soenke Ahrens' book "How to Take Smart Notes," he describes three types of notes: fleeting notes (these are fleeting ideas), literature notes, and permanent notes. In that classification, I'm talking about "literature notes." Ahrens says these should be "extremely selective". But with the material I'm talking about it becomes a question. How can you be selective when you still don't know which facts you care about or want to maintain enough detail in your notes so you don't foreclose the possibilities in the historical narrative too early?Perhaps this is just an unsolvable problem. Perhaps there is no choice but to maintain a discipline of taking "selective" literature notes. But there's something about the Zettelkasten method that gives me the feeling that my literature notes could be more detailed and chaotic and open to refinement later.Does my dilemma explained here resonate with anyone who has tried this method for intense historical writing? If so, I'd like to hear you thoughts, or better yet, see some concrete examples of how you've worked.

reply to u/ethanzanemiller at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/185xmuh/taking_notes_for_historical_writing/

Rather than spending time theorizing on the subject, particularly since you sound like you're neck-deep already, I would heartily recommend spending some time practicing it heavily within the area you're looking at. Through a bit of time and experience, more of your questions will become imminently clear, especially if you're a practicing historian.

A frequently missing piece to some of this puzzle for practicing academics is upping the level of how you read and having the ability to consult short pieces of books and articles rather than reading them "cover-to-cover" which is often unnecessary for one's work. Of particular help here, try Adler and Van Doren, and specifically their sections on analytical and syntopical reading.

In addition to the list of practicing historians I'd provided elsewhere on the topic, you might also appreciate sociologist Beatrice Webb's short appendix C in My Apprenticeship or her longer related text. She spends some time talking about handling dates and the database nature of querying collected facts and ideas to do research and to tell a story.

Also helpful might be Mill's article which became a chapter in one of his later books:

Perhaps u/danallosso may have something illuminating to add, or you can skim through his responses on the subject on Reddit or via his previous related writing: https://danallosso.substack.com/.

Enough historians and various other humanists have been practicing these broad methods for centuries to bear out their usefulness in researching and organizing their work. Read a bit, but truly: practice, practice, and more practice is going to be your best friend here.

Deutsch himself never theorized his index, treating it – like hiswhole focus on ‘facts’ – at face value.

https://zibaldone.substack.com/p/a-guide-to-zettelkasten-part-2-a

I showed up expecting a one pager on zettelkasten method and was surprised to find it was about reading. :)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9fP4zFQMXSw

The fun things usually happen at the messy edges. This description of zettelkasten is a perfect encapsulation of this, though it's not necessarily on the surface.

This is a well done encapsulation of what a zettelkasten. Watch it once, then practice for a bit. Knowing the process is dramatically different from practicing it. Too many people want perfection (perfection for them and from their perspective) and they're unlikely to arrive at it by seeing examples of others. The examples may help a bit, but after you've seen a few, you're not going to find a lot of insight without practicing it to see what works for you.

This could be compared with epigenetic factors with respect to health. The broad Rx may help, but epigenetic factors need to be taken into account.

Want a Simplified Zettelkasten? For Beginners by Dr Maddy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w15joVA4pIc

Very quick and to the point.

In reality, the research experience mattersmore than the topic.”

Extending off of this, is the reality that the research experience is far easier if one has been taught a convenient method, not only for carrying it out, but space to practice the pieces along the way.

These methods can then later be applied to a vast array of topics, thus placing method above topic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OrN0kaE6DkY<br /> Is The Zettelkasten Method Really The Best Personal Knowledge Management System? by Anthony Metivier

meh...

https://joonhyeokahn.substack.com/p/demystify-zettelkasten

If you've not already spent some time with the idea, this short one pager is unlikely to "demystify" anything. Yet another zk one-pager, and not one of the better ones.

Viel gelesen und vor allen Dingen begonnen, mit einem Zettelka-sten zu arbeiten, also Zettel vollgeschrieben. In den Zetteln habeich die Literatur, mit der ich mich vorwiegend beschäftigte, verar-beitet, also Soziologie und Philosophie. Damals habe ich vor allemDescartes und Husserl gelesen. In der soziologischen Theorie hatmich der frühe Funktionalismus beschäftigt, die Theorien von Mali-nowski und Radcliffe-Brown; dies schloß ein, daß ich mich auchsehr stark mit Kulturanthropologie und Ethnologie befaßte

With heavy early interest in anthropology, sociology and philosophy including Malinowski, it's more likely that Luhmann would have been trained in historical methods which included the traditions of note taking using card indices of that time.

https://github.com/flengyel/Zettel

An interesting looking and complete template example.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/16wj9uz/a_luhmannesque_zettelkasten_in_7_easy_steps/

One of the more compact, yet dense overviews of Luhmann's method.

The simple Zettelkasten Method:<br /> 1. Buy index cards 2. Buy a box 3. ??? 4. Profit

Methodenstreit mischten sich zahlreichenamhafte Historiker und andere Geisteswissenschaftlerein. Warburg leistete keinen direkten publizistischen Bei-trag, nahm jedoch, wie der Zettelkasten belegt, als passi-ver Beobachter intensiv an der Debatte teil.359

Karl Lamprecht was one of Warburg's first teachers in Bonn and Warburg had a section in his zettelkasten dedicated to him. While Warburg wasn't part of the broader public debate on Lamprecht's Methodenstreit (methodological dispute), his notes indicate that he took an active stance on thinking about it.

Consult footnote for more:

59 Vgl. Roger Chickering, »The Lamprecht Controversy«, in: Historiker- kontroversen, hrsg. von Hartmut Lehmann, Göttingen 20 0 0, S. 15 – 29

Ernst Bernheim,

Aby Warburg's (1866-1929) zettelkasten had references to Ernst Bernheim (1850-1942). Likelihood of his having read Lehrbuch der historischen Methode (1889) as potential inspiration for his own zettelkasten?

When did Warburg start his zettelkasten?

According to Wikipedia, Warburg began his study of art history, history and archaeology in Bonn in 1886. He finished his thesis in 1892, so he may have had access to Bernheim's work on historical method. I'll note that Bernheim taught history at the University of Göttingen and at the University of Bonn after 1875, so they may have overlapped and even known each other. We'll need more direct evidence to establish this connection and a specific passing of zettelkasten tradition, though it may well have been in the "air" at that time.

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/T382CLwAjsy3fmecf/how-to-take-smart-notes-ahrens-2017

ᔥ[[abramdemski]] in The Zettelkasten Method (accessed:: 2023-08-25 10:12:42)

Early this year, Conor White-Sullivan introduced me to the Zettelkasten method of note-taking.

This article was likely a big boost to the general idea of zettelkasten in the modern zeitgeist.

Note the use of the phrase "Zettelkasten method of note-taking" which would have helped to distinguish it from other methods and thus helping the phrase Zettelkasten method stick where previously it had a more generic non-name.

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/NfdHG6oHBJ8Qxc26s/the-zettelkasten-method-1

A somewhat early, comprehensive one page description of the zettelkasten method from September 2019.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/13nmcym/i_read_the_top_ten_zettelkasten_articles_on/

A list of some popular one-pagers on the Zettelkasten Method.

Read contemporaneously in May 2023

https://reasonabledeviations.com/2022/04/18/molecular-notes-part-1/

Maybe come back to read this???

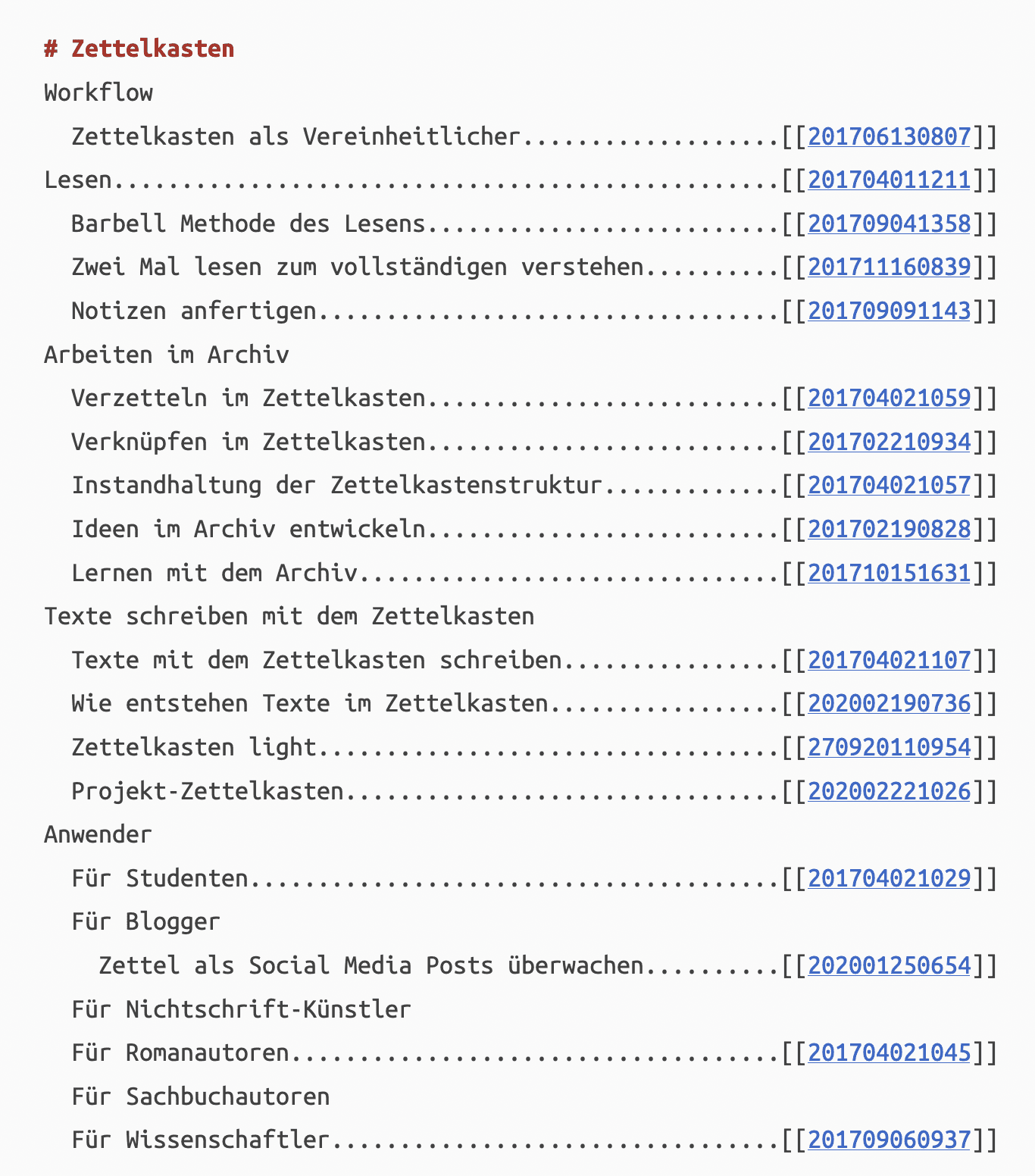

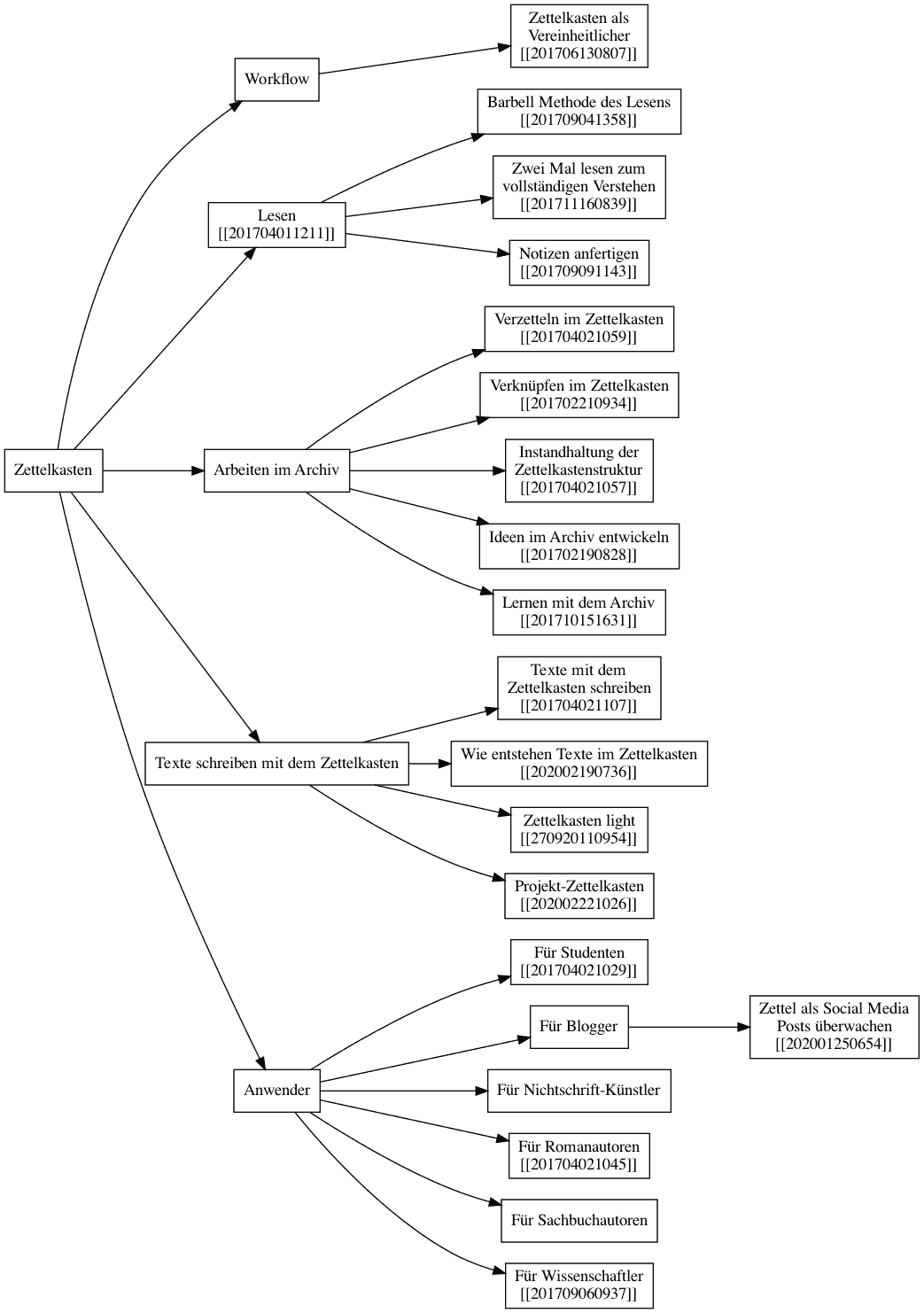

https://zettelkasten.de/posts/overview/

Good overview of the method and details for how to implement.

Possibly the king of the one page zettelkasten descriptions.

https://www.magneticmemorymethod.com/zettelkasten/

I'd found this page through general search and then a few days later someone from Metivier's "team" (an SEO hire likely) emailed me to link to it from a random zk page on my own site (not a great one).

Metivier seems to have come to ZK from the PKM space (via a podcast I listened to perhaps?). This page isn't horrible, but seems to benefit greatly from details I've added to the Wikipedia page over the past few years.

The command to schools—the invective about education—was, perhaps as ever, Janus-like: the injunction was to teach more and getbetter results, but to get kids to be imaginative and creative at the same time.They had to learn the facts of science, but they shouldn’t have original thinkingsqueezed from them in the process. It was the formal versus progressivecontroversy in a nutshell.

Can the zettelkasten method be a means of fixing/helping with this problem of facts versus creativity in a programmatic way?

There are many things that we have to take on trust; everyminute of every day we have to accept the testimony and the guidance of thosewho are in a position to offer an authoritative view.

Perhaps there is a need for balance between the two perspectives of formal and progressive education. While one can teach another the broad strokes of the "rules" of note taking, for example, using the zettelkasten method and even give examples of the good and the bad, the affordances, and tricks, individuals are still going to need to try things out to see what works for them in various situations and for their specific needs. In the end, its nice to have someone hand one the broad "rules" (and importantly the reasons for them), so that one has a set of tools which they can then practice as an art.

https://howaboutthis.substack.com/p/the-knowledge-that-wont-fit-inside-6d3

Reasonable one page overview of zettelkasten, though it undersells some of they "why."

Has a good list of some of the more popular one-two page articles floating around the blogosphere at the bottom.

natural one: we firstmust find something to say, then organize our material, and then put it intowords.

Finding something to say within a zettelkasten-based writing framework is relatively easy. One is regularly writing down their ideas with respect to other authors as part of "the great conversation" and providing at least a preliminary arrangement. As part of their conversation they're putting these ideas into words right from the start.

These all follow the basic pillars of classic rhetoric, though one might profitably take their preliminary written notes and continue refining the arrangement as well as the style of the writing as they proceed to finished product.

Heyde, Johannes Erich. Technik des wissenschaftlichen Arbeitens. (Sektion 1.2 Die Kartei) Junker und Dünnhaupt, 1931.

annotation target: urn:x-pdf:00126394ba28043d68444144cd504562

(Unknown translation from German into English. v1 TK)

The overall title of the work (in English: Technique of Scientific Work) calls immediately to mind the tradition of note taking growing out of the scientific historical methods work of Bernheim and Langlois/Seignobos and even more specifically the description of note taking by Beatrice Webb (1926) who explicitly used the phrase "recipe for scientific note-taking".

see: https://hypothes.is/a/BFWG2Ae1Ee2W1HM7oNTlYg

first reading: 2022-08-23 second reading: 2022-09-22

I suspect that this translation may be from Clemens in German to Scheper and thus potentially from the 1951 edition?

Heyde, Johannes Erich. Technik des wissenschaftlichen Arbeitens; eine Anleitung, besonders für Studierende. 8., Umgearb. Aufl. 1931. Reprint, Berlin: R. Kiepert, 1951.

the very point of a Zettelkasten is to ditch the categories.

If we believe as previously indicated by Luhmann's son that Luhmann learned the basics of his evolved method from Johannes Erich Heyde, then the point of the original was all about categories and subject headings. It ultimately became something which Luhmann minimized, perhaps in part for the relationship of work and the cost of hiring assistants to do this additional manual labor.

Understanding Zettelkasten notes <br /> by Mitch (@sacredkarailee@me.dm) 2022-02-11

Quick one pager overview which actually presumes you've got some experience with the general idea. Interestingly it completely leaves out the idea of having an index!

Otherwise, generally: meh. Takes a very Ahrens-esque viewpoint and phraseology.

Luhmann’s Zettelkasten does not show the Zettelkasten Method

what is the meaning of "the" here (which is italicized for emphasis)?!?

I got rid of most of the features after I realized that they are redundant or a just plain harmful when they slowed me down.

Many long time practitioners of note taking methods, particularly in the present environment enamored with shiny object syndrome, will advise to keep one's system as simple as possible. Sascha Fast has specifically said, "I got rid of most of the features after I realized that they are redundant or a (sic) just plain harmful when they slowed me down."

Living with a Zettelkasten | Blay <br /> by Magnus Eriksson at 2015-06-21 <br /> (accessed:: 2023-02-23 06:40:39)

a zettelkasten method one pager based generally on Luhmann's example and broadly drawn from material only on zettelkasten.de up to the date of writing in 2015.

Interesting to see the result of a single source without any influence from Ahrens, Eco, or any others from what I can tell. Perhaps some influence from Kuehn, but only from the overlap of zettelkasten.de and Kuehn's blog.

Note that it's not as breathless as many one page examples and doesn't focus on Luhmann's massive output, but it's still also broadly devoid of any other history or examples.

I would have hoped for more on the "living with" portion that was promised.

The Zettelkasten Method is not a thing; it is a manual to productivity.

Herbert Baxton Adams’ model of ahistorical seminar room suggested it have a dedicated catalogue;

Deutsch’s index was created out of an almost algorith-mic processing of historical sources in the pursuit of a totalized and perfect history of theJews; it presented, on one hand, the individualized facts, but together also constitutedwhat we might term a ‘history without presentation’, which merely held the ‘facts’themselves without any attempt to synthesize them (cf. Saxer, 2014: 225-32).

Not sure that I agree with the framing of "algorithmic processing" here as it was done manually by a person pulling out facts. But it does bring out the idea of where collecting ends and synthesis of a broader thesis out of one's collection begins. Where does historical method end? What was the purpose of the collection? Teaching, writing, learning, all, none?

one finds in Deutsch’s catalogue one implementation of what LorraineDaston would later term ‘mechanical objectivity’, an ideal of removing the scholar’s selffrom the process of research and especially historical and scientific representation (Das-ton and Galison, 2007: 115-90).

In contrast to the sort of mixing of personal life and professional life suggested by C. Wright Mills' On Intellectual Craftsmanship (1952), a half century earlier Gotthard Deutsch's zettelkasten method showed what Lorraine Datson would term 'mechanical objectivity'. This is an interesting shift in philosophical perspective of note taking practice. It can also be compared and contrasted with a 21st century perspective of "personal" knowledge management.

Around 1956: "My next task was to prepare my course. Since none of the textbooks known to me was satisfactory, I resorted to the maieutic method that Plato had attributed to Socrates. My lectures consisted essentially in questions that I distributed beforehand to the students, and an abstract of the research that they had prompted. I wrote each question on a 6 × 8 card. I had adopted this procedure a few years earlier for my own work, so I did not start from scratch. Eventually I filled several hundreds of such cards, classed them by subject, and placed them in boxes. When a box filled up, it was time to write an article or a book chapter. The boxes complemented my hanging-files cabinet, containing sketches of papers, some of them aborted, as well as some letters." (p. 129)

This sounds somewhat similar to Mark Robertson's method of "live Roaming" (using Roam Research during his history classes) as a teaching tool on top of other prior methods.

link to: Roland Barthes' card collection for teaching: https://hypothes.is/a/wELPGLhaEeywRnsyCfVmXQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpvEY-2dSdU

In this episode, I explain the memory system I created in order to expand my memory to new heights. I call it the Sirianni Method and with it, you can learn how to create an intentional photographic memory.

Who the hell is the Sirianni this is named for, himself? (In the comments he mentions that "it's my italian grandpa's last name, I always liked it and a while back started naming things after it)

tl;dr: He's reinvented the wheel, but certainly not the best version of it.

What he's describing isn't remotely related to the idea of a photographic memory, so he's over-hyping the results, which is dreadful. If it were a photographic memory, he wouldn't need the spaced-repetition portion of his practice. While he mentions how he's regularly reviewing his cards he doesn't mention any of the last century+ of research and work on spaced repetition. https://super-memory.com/articles/20rules.htm is a good place to start for some of this.

A lot of what he's doing is based on associative memory, particularly by drawing connections/links to other things he already knows. He's also taking advantage of visual memory by associating his knowledge with a specific picture.

He highlights emotion and memory, but isn't drawing clear connections between his knowledge and any specific emotions that he's tying or associating them to.

"Intentional" seems to be one of the few honest portions of the piece.

Overview of his Sirianni method: pseudo-zettelkasten notes with written links to things he already knows (but without any Luhmann-esque numbering system or explicit links between cards, unless they're hiding in his connections section, which isn't well supported by the video) as well as a mnemonic image and lots of ad hoc spaced repetition.

One would be better off mixing their note taking practice with associative mnemonic methods (method of loci, songlines, memory palaces, sketchnotes, major system, orality, etc.) all well described by Lynne Kelly (amongst hundreds before her who got smaller portions of these practices) in combination with state of the art spaced repetition.

The description of Luhmann's note taking system here is barely passable at best. He certainly didn't invent the system which was based on several hundred years of commonplace book methodology before him. Luhmann also didn't popularize it in any sense (he actually lamented how people were unimpressed by it when he showed them). Popularization was done post-2013 generally by internet hype based on his prolific academic output.

There is nothing new here other than that he thinks he's discovered something new and is repackaging it for the masses with a new name in a flashy video package. There's a long history of hucksters doing this sort of fabulist tale including Kevin Trudeau with Mega Memory in the 1990s and going back to at least the late 1800s with "Professor" Alphonse Loisette and the system he sold for inordinate amounts to the masses including Mark Twain.

Most of these methods have been around for millennia and are all generally useful and well documented though the cultural West has just chosen to forget most of them. A week's worth of research and reading on these topics would have resulted in a much stronger "system" more quickly.

Beyond this, providing a fuller range of specific options and sub-options in these areas so that individuals could pick and choose the specifics which work best for them might have been a better way to go.

Content research: D- Production value: A+

{syndication link](https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/10ehrbd/comment/j4u495q/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3)

For some scholars, it is critical thatthis new Warburg obsessively kept tabs on antisemitic incidents on the Easternfront, scribbling down aphorisms and thoughts on scraps of paper and storingthem in Zettelkasten that are now searchable.

Apparently Aby Warburg "obsessively kept" notes on antisemitic incidents on the Eastern front in his zettelkasten.

This piece looks at Warburg's Jewish identity as supported or not by the contents of his zettelkasten, thus placing it in the use of zettelkasten or card index as autobiography.

Might one's notes reflect who they were as a means of creating both their identity while alive as well as revealing it once they've passed on? Might the use of historical method provide its own historical method to be taken up on a meta basis after one's death?

Is the ZK method worth it? and how it helped you in your projects? .t3_zwgeas._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } questionI am new to ZK method and I'd like to use it for my literature review paper. Altho the method is described as simple, watching all those YT videos about the ZK and softwares make it very complex to me. I want to know how it changed your writing??

reply to u/Subject_Industry1633 at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/zwgeas/is_the_zk_method_worth_it_and_how_it_helped_you/ (and further down)

ZK is an excellent tool for literature reviews! It is a relative neologism (with a slightly shifted meaning in English over the past decade with respect to its prior historical use in German) for a specific form of note taking or commonplacing that has generally existed in academia for centuries. Excellent descriptions of it can be found littered around, though not under a specific easily searchable key word or phrase, though perhaps phrases like "historical method" or "wissenschaftlichen arbeitens" may come closest.

Some of the more interesting examples of it being spelled out in academe include:

For academic use, anecdotally I've seen very strong recent use of the general methods most compellingly demonstrated in Obsidian (they've also got a Discord server with an academic-focused channel) though many have profitably used DevonThink and Tinderbox (which has a strong, well-established community of academics around it) as much more established products with dovetails into a variety of other academic tools. Obviously there are several dozens of newer tools for doing this since about 2018, though for a lifetime's work, one might worry about their longevity as products.

A beautiful example of a note that imbeds core zettels that simultaneously make connections within a Zettelkasten. Each page for a note displays the network of notes and their connections. The website is based on an open-source template

The source code for the site is here

This is a doctrine so practically important that we could have wismore than two pages of the book had been devoted to note-takiand other aspects of the " Plan and Arrangement of CollectionsContrariw

In the 1923 short notices section of the journal History, one of the editors remarked in a short review of "The Mechanical Processes of the Historian" that they wished that Charles Johnson had spent more than two pages of the book on note taking and "other aspects of the 'Plan and Arrangement of Collections'" as the zettelkasten "is a doctrine so practically important" to historians.

T., T. F., A. F. P., E. R. A., H. E. E., R. C., E. L. W., F. J. C. H., and E. J. C. “Short Notices.” History 8, no. 31 (1923): 231–37.

Pomeroy, Earl. “Frederic L. Paxson and His Approach to History.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 39, no. 4 (1953): 673–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/1895394

read on 2022-10-30 - 10-31

Paxson wrote several unusually sharp reviews of books by Mc-Master, Rhodes, and Ellis P. Oberholtzer, historians whose methodshave been compared with his own

Examples of other historians who likely had a zettelkasten method of work.

Rhodes' method is tangentially mentioned by Earle Wilbur Dow as being "notebooks of the old type". https://hypothes.is/a/PuFGWCRMEe2bnavsYc44cg

the writer of "scissors and paste history" ;

One cannot excerpt their way into knowledge, simply cutting and pasting one's way through life is useless. Your notes may temporarily serve you, but unless you apply judgement and reason to them to create something new, they will remain a scrapheap for future generations who will gain no wisdom or use from your efforts.

relate to: notes about notes being only useful to their creator

It is possible this Miscellany collection was assembled by Schutz as part of his own research as an historian, as well as the letters and documents collected as autographs for his interest as a collector;

https://catalog.huntington.org/record=b1792186

Is it possible that this miscellany collection is of a zettelkasten nature?

Found via a search of the Huntington Library for Frederic L. Paxson's zettelkasten

Preceding anyspecific historiographical method, the Zettelkasten provides the space inwhich potential constellations between these things can appear concretely,a space to play with connections as they have been formed by historic pre-decessors or might be formed in the present.

relationship with zettelkasten in the history of historical methods?

Cattell, J. McKeen. “Methods for a Card Index.” Science 10, no. 247 (1899): 419–20.

Columbia professor of psychology calls for the creation of a card index of references to reviews and abstracts for areas of research. Columbia was apparently doing this in 1899 for the psychology department.

What happened to this effort? How similar was it to the system of advertising cards for books in Germany in the early 1930s described by Heyde?

Goutor doesn't specifically cover the process, but ostensibly after one has categorized content notes, they are filed together in one's box under that heading. (p34) As a result, there is no specific indexing or cross-indexing of cards or ideas which might be filed under multiple headings. In fact, he doesn't approach the idea of filing under multiple headings at all, while authors like Heyde (1931) obsess over it. Goutor's method also presumes that the creation of some of the subject headings is to be done in the planning stages of the project, though in practice some may arise as one works. This process is more similar to that seen in Robert Greene's commonplacing method using index cards.

In "On Intellectual Craftsmanship" (1952), C. Wright Mills talks about his methods for note taking, thinking, and analysis in what he calls "sociological imagination". This is a sociologists' framing of their own research and analysis practice and thus bears a sociological related name. While he talks more about the thinking, outlining, and writing process rather than the mechanical portion of how he takes notes or what he uses, he's extending significantly on the ideas and methods that Sönke Ahrens describes in How to Take Smart Notes (2017), though obviously he's doing it 65 years earlier. It would seem obvious that the specific methods (using either files, note cards, notebooks, etc.) were a bit more commonplace for his time and context, so he spent more of his time on the finer and tougher portions of the note making and thinking processes which are often the more difficult parts once one is past the "easy" mechanics.

While Mills doesn't delineate the steps or materials of his method of note taking the way Beatrice Webb, Langlois & Seignobos, Johannes Erich Heyde, Antonin Sertillanges, or many others have done before or Umberto Eco, Robert Greene/Ryan Holiday, Sönke Ahrens, or Dan Allosso since, he does focus more on the softer portions of his thinking methods and their desired outcomes and provides personal examples of how it works and what his expected outcomes are. Much like Niklas Luhmann describes in Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1981), Mills is focusing on the thinking processes and outcomes, but in a more accessible way and with some additional depth.

Because the paper is rather short, but specific in its ideas and methods, those who finish the broad strokes of Ahrens' book and methods and find themselves somewhat confused will more than profit from the discussion here in Mills. Those looking for a stronger "crash course" might find that the first seven chapters of Allosso along with this discussion in Mills is a straighter and shorter path.

While Mills doesn't delineate his specific method in terms of physical tools, he does broadly refer to "files" which can be thought of as a zettelkasten (slip box) or card index traditions. Scant evidence in the piece indicates that he's talking about physical file folders and sheets of paper rather than slips or index cards, but this is generally irrelevant to the broader process of thinking or writing. Once can easily replace the instances of the English word "file" with the German concept of zettelkasten and not be confused.

One will note that this paper was written as a manuscript in April 1952 and was later distributed for classroom use in 1955, meaning that some of these methods were being distributed from professor to students. The piece was later revised and included as an appendix to Mill's text The Sociological Imagination which was first published in 1959.

Because there aren't specifics about Mills' note structure indicated here, we can't determine if his system was like that of Niklas Luhmann, but given the historical record one could suppose that it was closer to the commonplace tradition using slips or sheets. One thing becomes more clear however that between the popularity of Webb's work and this (which was reprinted in 2000 with a 40th anniversary edition), these methods were widespread in the mid-twentieth century and specifically in the field of sociology.

Above and beyond most of these sorts of treatises on note taking method, Mills does spend more time on the thinking portions of the practice and delineates eleven different practices that one can focus on as they actively read/think and take notes as well as afterwards for creating content or writing.

My full notes on the article can be found at https://jonudell.info/h/facet/?user=chrisaldrich&max=100&exactTagSearch=true&expanded=true&addQuoteContext=true&url=urn%3Ax-pdf%3A0138200b4bfcde2757a137d61cd65cb8

But even if onewere to create one’s own classification system for one’s special purposes, or for a particularfield of sciences (which of course would contradict Dewey’s claim about general applicabilityof his system), the fact remains that it is problematic to press the main areas of knowledgedevelopment into 10 main areas. In any case it seems undesirable having to rely on astranger’s

imposed system or on one’s own non-generalizable system, at least when it comes to the subdivisions.

Heyde makes the suggestion of using one's own classification system yet again and even advises against "having to rely on a stranger's imposed system". Does Luhmann see this advice and follow its general form, but adopting a numbering system ostensibly similar, but potentially more familiar to him from public administration?

It is obvious that due to this strict logic foundation, related thoughts will not be scattered allover the box but grouped together in proximity. As a consequence, completely withoutcarbon-copying all note sheets only need to be created once.

In a break from the more traditional subject heading filing system of many commonplacing and zettelkasten methods, in addition to this sort of scheme Heyde also suggests potentially using the Dewey Decimal System for organizing one's knowledge.

While Luhmann doesn't use Dewey's system, he does follow the broader advice which allows creating a dense numbering system though he does use a different numbering scheme.

The layout and use of the sheet box, as described so far, is eventually founded upon thealphabetical structure of it. It should also be mentioned though

that the sheetification can also be done based on other principles.

Heyde specifically calls the reader to consider other methods in general and points out the Dewey Decimal Classification system as a possibility. This suggestion also may have prompted Luhmann to do some evolutionary work for his own needs.

re all filed at the same locatin (under “Rehmke”) sequentially based onhow the thought process developed in the book. Ideally one uses numbers for that.

While Heyde spends a significant amount of time on encouraging one to index and file their ideas under one or more subject headings, he address the objection:

“Doesn’t this neglect the importance of sequentiality, context and development, i.e. doesn’t this completely make away with the well-thought out unity of thoughts that the original author created, when ideas are put on individual sheets, particularly when creating excerpts of longer scientific works?"

He suggests that one file such ideas under the same heading and then numbers them sequentially to keep the original author's intention. This might be useful advice for a classroom setting, but perhaps isn't as useful in other contexts.

But for Luhmann's use case for writing and academic research, this advice may actually be counter productive. While one might occasionally care about another author's train of thought, one is generally focusing on generating their own train of thought. So why not take this advice to advance their own work instead of simply repeating the ideas of another? Take the ideas of others along with your own and chain them together using sequential numbers for your own purposes (publishing)!!

So while taking Heyde's advice and expand upon it for his own uses and purposes, Luhmann is encouraged to chain ideas together and number them. Again he does this numbering in a way such that new ideas can be interspersed as necessary.

If a more extensive note has been put on several A6 sheets subsequently,

Heyde's method spends almost a full page talking about what to do if one extends a note or writes longer notes. He talks about using larger sheets of paper, carbon copies, folding, dating, clipping, and even stapling.

His method seems to skip the idea of extending a particular card of potentially 2 or more "twins"/"triplets"/"quadruplets" which might then also need to be extended too. Luhmann probably had a logical problem with this as tracking down all the originals and extending them would be incredibly problematic. As a result, he instead opted to put each card behind it's closest similar idea (and number it thus).

If anything, Heyde's described method is one of the most complete of it's day (compare with Bernheim, Langlois/Seignobos, Webb, Sertillanges, et al.) He discusses a variety of pros and cons, hints and tips, but he also goes deeper into some of the potential flaws and pitfalls for the practicing academic. As a result, many of the flaws he discusses and their potential work arounds (making multiple carbon copies, extending notes, etc.) add to the bulk of the description of the system and make it seem almost painful and overbearing for the affordances it allows. As a result, those reading it with a small amount of knowledge of similar traditions may have felt that there might be a better or easier system. I suspect that Niklas Luhmann was probably one of these.

It's also likely that due to these potentially increasing complexities in such note taking systems that they became to large and unwieldly for people to see the benefit in using. Combined with the emergence of the computer from this same time forward, it's likely that this time period was the beginning of the end for such analog systems and experimenting with them.

I have a strong feeling it's just as experimental and playful in design as writing with a Zettelkasten

In February 2018, Christian Tietze noted some similarities to Luhmann's zettelkasten methods and that of Gerald Weinberg's Fieldstone wall method of writing.

Students' annotations canprompt first draft thinking, avoiding a blank page when writing andreassuring students that they have captured the critical informationabout the main argument from the reading.

While annotations may prove "first draft thinking", why couldn't they provide the actual thinking and direct writing which moves toward the final product? This is the sort of approach seen in historical commonplace book methods, zettelkasten methods, and certainly in Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten incarnation as delineated by Johannes Schmidt or variations described by Sönke Ahrens (2017) or Dan Allosso (2022)? Other similar variations can be seen in the work of Umberto Eco (MIT, 2015) and Gerald Weinberg (Dorset House, 2005).

Also potentially useful background here: Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. Yale University Press, 2010. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300165395/too-much-know

Jeff Miller@jmeowmeowReading the lengthy, motivational introduction of Sönke Ahrens' How to Take Smart Notes (a zettelkasten method primer) reminds me directly of Gerald Weinberg's Fieldstone Method of writing.

reply to: https://twitter.com/jmeowmeow/status/1568736485171666946

I've only seen a few people notice the similarities between zettelkasten and fieldstones. Among them I don't think any have noted that Luhmann and Weinberg were both systems theorists.

Sometimes it will be enoughto have analysed the text mentally : it is not alwaysnecessary to put down in black and white the wholecontents of a document ; in such cases we simplyenter the points of which we intend to make use.But against the ever-present danger oi substitutingone's personal impressions for the text there is onlyone real safeguard ; it should be made an invariablerule never on any account to make an extract froma document, or a partial analysis of it, without

having first made a comprehensive analysis of it mentally, if not on paper.

if there is occasion for it, and a heading^ in anycase; to multiply cross-references and indices; tokeep a record, on a separate set of slips, of all thesources utilised, in order to avoid the danger ofhaving to work a second time through materialsaheady dealt with. The regular observance of thesemaxims goes a great way towards making scientifichistorical work easier and more solid.

But it will always be well to cultivate the mechanical habits of which pro- fessional compilers have learnt the value by experi- ence: to write at the head of evey slip its date,

Here again we see some broad common advice for zettels and note taking methods: - every slip or note should have a date - every slip should have a (topical) heading - indices - cross-references - lists of sources (bibliography)

It isrecommended to use slips of uniform size and toughmaterial, and to arrange them at the earliest oppor-tunity in covers or drawers or otherwise.

common zettelkasten keeping advice....

The notes from each document are entered upon aloose leaf furnished with the precisest possible in-dications of origin. The advantages of this artificeare obvious : the detachability of the slips enablesus to group them at will in a host of different com-binations ; if necessary, to change their places : it iseasy to bring texts of the same kind together, andto incorporate additions, as they are acquired, in theinterior of the groups to which they belong. As fordocuments which are interesting from several pointsof view, and which ought to appear in several groups,it is sufficient to enter them several times over ondifferent slips ; or they may be represented, as oftenas may be required, on reference-slips.

Notice that at the bottom of the quote that they indicate that in addition to including multiple copies of a card in various places, a plan which may be inefficient, they indicate that one can add reference-slips in their place.

This is closely similar to, but a small jump away from having explicit written links on the particular cards themselves, but at least mitigates the tedious copying work while actively creating links or cross references within one's note taking system.

But Ms. Rivers did do some arranging. She arranged the 52 drawers alphabetically by subject, from “Annoying habits” to “Zoo.” In the T’s, one drawer starts with “Elizabeth Taylor” and goes as far as “teenagers.” The next drawer picks up with “teeth” and runs to “trains.” A drawer in the G’s begins with “growing older” and ends with “guns.” It takes the next drawer to hold all the cards filed under “guys I dated.” Inevitably — this was Joan Rivers, after all — there are categories with the word “sex,” including “My sex life,” “No sex life,” “No sex appeal.”AdvertisementContinue reading the main storyImage

In discussing the various ways Luhmann referenced his notes, Schmidt discusses specific notes created by Luhmann that appeared to produce "larger structural outline[s]."8 It seems, when beginning a major line of thought, Luhmann created a note that resembled "the outline of an article or table of contents of a book."9 Today, many call these outline notes "structure notes," a term which has come to prominence through its usage on the zettelkasten.de forum.

Definition and inclusion criteria

Further to [[User:Biogeographist|Biogeographist]]'s comments about what defines a zettelkasten, someone has also removed the Eminem example (https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Zettelkasten&type=revision&diff=1105779799&oldid=1105779647) which by the basest of definitions is a zettelkasten being slips of paper literally stored in a box. The continually well-documented path of the intellectual history of the tradition stemming out of the earlier Commonplace book tradition moved from notebooks to slips of paper indicates that many early examples are just this sort of collection. The optional addition of subject headings/topics/tags aided as a finding mechanism for some and was more common historically. Too much of the present definition on the page is dominated by the recently evolved definition of a zettelkasten as specifically practiced by Luhmann, who is the only well known example of a practitioner who heavily interlinked his cards as well as indexed them (though it should be noted that they were only scantly indexed as entry points into the threads of linked cards which followed). The broader historical perspective of the practice is being overly limited by the definition imprinted by a single example, the recent re-discovery of whom, has re-popularized a set of practices dating back to at least the sixteenth century.

It seems obvious that through the examples collected and the scholarship of Blair, Cevollini, Krajewski, and others that collections of notes on slips generally kept in some sort of container, usually a box or filing cabinet of some sort is the minimal definition of the practice. This practice is often supplemented by additional finding and linking methods. Relying on the presence of ''metadata'' is both a limiting (and too modern) perspective and not supported by the ever-growing numbers of historical examples within the space.

Beyond this there's also a modern over-reliance (especially in English speaking countries beginning around 2011 and after) on the use and popularity of the German word Zettelkasten which is not generally seen in the historically English and French speaking regions where "card index" and "fichier boîte" have been used for the same practices. This important fact was removed from the top level definition with revision https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Zettelkasten&type=revision&diff=1105779647&oldid=1105766061 and should also be reverted to better reflect the broader idea and history.

In short, the definition, construction, and evolution of this page/article overall has been terribly harmed by an early definition based only on Niklas Luhmann's practice as broadly defined within the horribly unsourced and underinformed blogosphere from approximately 2013 onward. ~~~~

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o49C8jQIsvs

Video about the Double-Bubble Map: https://youtu.be/Hm4En13TDjs

The double-bubble map is a tool for thought for comparing and contrasting ideas. Albert Rosenberg indicates that construction of opposites is one of the most reliable ways for generating ideas. (35:50)

Bluma Zeigarnik - open tasks tend to occupy short-term memory.

I love his compounding interest graphic with the steps moving up to the right with the quote: "Even groundbreaking paradigm shifts are most often the consequence of many small moves in the right direction instead of one big idea." This could be an awesome t-shirt or motivational poster.

Watched this up to about 36 minutes on 2022-08-10 and finished on 2022-08-22.

Bernheim, Ernst. Lehrbuch der historischen Methode und der Geschichtsphilosophie: mit Nachweis der wichtigsten Quellen und Hilfsmittel zum Studium der Geschichte. Leipzig : Duncker & Humblot, 1908. http://archive.org/details/lehrbuchderhist03berngoog.

Title translation: Textbook of the historical method and the philosophy of history : with reference to the most important sources and aids for the study of history

A copy of the original 1889 copy can be found at https://digital.ub.uni-leipzig.de/mirador/index.php

3. Regesten.Da wir gesehen haben, wieviel auf tibersichtliche Ordnungbei der Zusammenstellung des Materials ankommt, muff manauf die praktische Einrichtung seiner Materialiensammlung vonAnfang an bewufte Sorgfalt verwenden. Selbstverstindlichlassen sich keine, im einzelnen durchweg gtiltigen Regeln auf-stellen; aber wir kinnen uns doch tiber einige allgemeine Ge-sichtspunkte verstindigen. Nicht genug zu warnen ist vor einemregel- und ordnungslosen Anhiufen und Durcheinanderschreibender Materialien; denn die zueinander gehérigen Daten zusammen--gufinden erfordert dann ein stets erneutes Durchsehen des ganzenMaterials; auch ist es dann kaum miglich, neu hinzukommendeDaten an der gehirigen Stelle einzureihen. Bei irgend gréferenArbeiten muff man seine Aufzeichnungen auf einzelne loseBlatter machen, die leicht umzuordnen und denen ohne Unm-stinde Blatter mit neuen Daten einzuftigen sind. Macht mansachliche Kategorieen, so sind die zu einer Kategorie gehérigenBlatter in Umschligen oder besser noch in K&sten getrennt zuhalten; innerhalb derselben kann man chronologisch oder sach-lich alphabetisch nach gewissen Schlagwiértern ordnen.

- Regesten Da wir gesehen haben, wieviel auf tibersichtliche Ordnung bei der Zusammenstellung des Materials ankommt, muß man auf die praktische Einrichtung seiner Materialiensammlung von Anfang an bewußte Sorgfalt verwenden. Selbstverständlich lassen sich keine, im einzelnen durchweg gültigen Regeln aufstellen; aber wir können uns doch über einige allgemeine Gesichtspunkte verständigen. Nicht genug zu warnen ist vor einem regel- und ordnungslosen Anhäufen und Durcheinanderschreiben der Materialien; denn die zueinander gehörigen Daten zusammenzufinden erfordert dann ein stets erneutes Durchsehen des ganzen Materials; auch ist es dann kaum möglich, neu hinzukommende Daten an der gehörigen Stelle einzureihen. Bei irgend größeren Arbeiten muß man seine Aufzeichnungen auf einzelne lose Blätter machen, die leicht umzuordnen und denen ohne Umstände Blätter mit neuen Daten einzufügen sind. Macht man sachliche Kategorieen, so sind die zu einer Kategorie gehörigen Blätter in Umschlägen oder besser noch in Kästen getrennt zu halten; innerhalb derselben kann man chronologisch oder sachlich alphabetisch nach gewissen Schlagwörtern ordnen.

Google translation:

- Regesture Since we have seen how much importance is placed on clear order in the gathering of material, conscious care must be exercised in the practical organization of one's collection of materials from the outset. It goes without saying that no rules that are consistently valid in detail can be set up; but we can still agree on some general points of view. There is not enough warning against a disorderly accumulation and jumble of materials; because to find the data that belong together then requires a constant re-examination of the entire material; it is also then hardly possible to line up newly added data at the appropriate place. In any large work one must make one's notes on separate loose sheets, which can easily be rearranged, and sheets of new data easily inserted. If you make factual categories, the sheets belonging to a category should be kept separate in covers or, better yet, in boxes; Within these, you can sort them chronologically or alphabetically according to certain keywords.

In a pre-digital era, Ernst Bernheim warns against "a disorderly accumulation and jumble of materials" (machine translation from German) as it means that one must read through and re-examine all their collected materials to find or make sense of them again.

In digital contexts, things are vaguely better as the result of better search through a corpus, but it's still better practice to have things with some additional level of order to prevent the creation of a "scrap heap".

link to: - https://hyp.is/i9dwzIXrEeymFhtQxUbEYQ

In 1889, Bernheim suggests making one's notes on separate loose sheets of paper so that they may be easily rearranged and new notes inserted. He suggested assigning notes to categories and keeping them separated, preferably in boxes. Then one might sort them in a variety of different ways, specifically highlighting both chronological and alphabetical order based on keywords.

(This quote is from the 1903 edition, but presumably is similar or the same in 1889, but double check this before publishing.)

Link this to the earlier section in which he suggested a variety of note orders for historical methods as well as for the potential creation of insight into one's work.

Man sieht, die stoffliche Ordnung setzt bereits bestimmteGesichtspunkte voraus und ist daher durch die ,Auffassung“bedingt; allein bei tibersichtlicher Materialordnung werden wirauch umgekehrt oft genug durch sich anhtufende Daten einergewissen von uns anfangs nicht erwarteten Art auf ganz neueGesichtspunkte unseres Themas aufmerksam gemacht.

Google translation:

One sees that the material order already sets certain ones points of view ahead and is therefore conditional; only with a clear arrangement of the material will we also vice versa often enough due to accumulating data in a way that we didn't expect at first, in a completely new way points of view of our topic.

While discussing the various orders of research material, Ernst Bernheim mentions the potential of accumulating data and arranging it in various manners such that we obtain new points of view in unexpected ways. This sounds quite similar to a process of idea generation similar to combinatorial creativity, though not as explicit.

The process creates the creativity, but isn't necessarily used to force the creativity here.

While he doesn't point out a specific generative mechanism for the creation of the surprise, it's obvious that his collection and collation method underpins it.

The box makes me feel connected to a project. It is my soil. I feel this evenwhen I’ve back-burnered a project: I may have put the box away on a shelf, but Iknow it’s there. The project name on the box in bold black lettering is a constantreminder that I had an idea once and may come back to it very soon.

Having a physical note taking system also stands as a physical reminder and representation of one's work and focus. It may be somewhat out of the way on a shelf, but it takes up space in a way that digital files and notes do not. This invites one into using and maintaining it.

Link to - tying a string on one's finger as a reminder - method of loci - orality

*The compass*

I too have seen this before, though the directions may have been different.

When thinking about an idea, map it discretely. North on the compass rose is where the idea comes from, South is where it leads to, West leads to things similar to the idea while East are ideas that are the opposite of it.

This is useful in situating information, particularly with respect to the similarities and opposites. One must generally train themselves to think about the opposites.

Many of the directions are directly related to putting information into a zettelkasten, in particular where X comes from (source), where it leads (commentary or links to other ides), what's similar to x are links to either closely related ideas or to an index. The opposite of X is the one which is left out in this system too.

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>*The compass*: <br>Saw that one before. Ugh, didn't like it.<br><br>Thinking about it though, it's a fitting metaphor to look at a note from different directions. I'm going to add this to my notes template(Just to try). All my notes have North & could use some other perspectives 🎉<br><br>🧶4/4 pic.twitter.com/CJctmC5Y39

— Alex Qwxlea (@QwxleaA) June 14, 2022

Link to - Indigenous map conceptualizations - direction finding - method of loci

9/8g Hinter der Zettelkastentechnik steht dieErfahrung: Ohne zu schreiben kann mannicht denken – jedenfalls nicht in anspruchsvollen,selektiven Zugriff aufs Gedächtnis voraussehendenZusammenhängen. Das heißt auch: ohne Differenzen einzukerben,kann man nicht denken.

Google translation:

9/8g The Zettelkasten technique is based on experience: You can't think without writing—at least not in contexts that require selective access to memory.

That also means: you can't think without notching differences.

There's something interesting about the translation here of "notching" occurring on an index card about ideas which can be linked to the early computer science version of edge-notched cards. Could this have been a subtle and tangential reference to just this sort of computing?

The idea isn't new to me, but in the last phrase Luhmann tangentially highlights the value of the zettelkasten for more easily and directly comparing and contrasting the ideas on two different cards which might be either linked or juxtaposed.

Link to:

Shield of Achilles and ekphrasis thesis

https://hypothes.is/a/I-VY-HyfEeyjIC_pm7NF7Q With the further context of the full quote including "with selective access to memory" Luhmann seemed to at least to make space (if not give a tacit nod?) to oral traditions which had methods for access to memories in ways that modern literates don't typically give any credit at all. Johannes F.K .Schmidt certainly didn't and actively erased it in Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: The Fabrication of Serendipity.

When Should You Start a New Note?

note taking suggestions

Goal, is to figure out if I can do this with Notion.

The zettel is the smallest unit, a note entered into the system. It requires a unique identifier, the body/content for the note, and footer/references.

Actively include citations to other Zettels.

Two types of structures depicted graphically

To make the most of a connection, always state explicitly why you made it. This is the link context. An example link context looks like this:

So ACTIVELY include the equivalent of citations to other ZETTELS.

The most important aspect of the body of the Zettel is that you write it in your own words. There is nothing wrong with capturing a verbatim quote on top. But one of the core rules to make the Zettelkasten work for you is to use your own words, instead of just copying and pasting something you believe is useful or insightful. This forces you to at least create a different version of it, your own version. This is one of the steps that lead to increased understanding of the material, and it improves recall of the information you process. Your Zettelkasten will truly be your own if its content is yours and not just a bunch of thoughts of other people.

If you enter the content in your own words you take active ownership. Also, as a grad student, you don't want the extra work of not only finding the reference you'd like to allude to but additionally having to rephrase it at the time of writing a paper or book.

A Zettelkasten is a personal tool for thinking and writing. It has hypertextual features to make a web of thought possible. The difference to other systems is that you create a web of thoughts instead of notes of arbitrary size and form, and emphasize connection, not a collection

definition

Communicating with Slip Boxes An Empirical Account Niklas Luhmann

Manual for the Zettelkasten method from the man himself.