Historical Hypermedia: An Alternative History of the Semantic Web and Web 2.0 and Implications for e-Research. .mp3. Berkeley School of Information Regents’ Lecture. UC Berkeley School of Information, 2010. https://archive.org/details/podcast_uc-berkeley-school-informat_historical-hypermedia-an-alte_1000088371512. archive.org.

https://www.ischool.berkeley.edu/events/2010/historical-hypermedia-alternative-history-semantic-web-and-web-20-and-implications-e.

https://www.ischool.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/audio/2010-10-20-vandenheuvel_0.mp3

Interface as Thing - book on Paul Otlet (not released, though he said he was working on it)

- W. Boyd Rayward 1994 expert on Otlet

- Otlet on annotation, visualization, of text

- TBL married internet and hypertext (ideas have sex)

- V. Bush As We May Think - crosslinks between microfilms, not in a computer context

- Ted Nelson 1965, hypermedia

t=540

- Michael Buckland book about machine developed by Emanuel Goldberg antecedent to memex

- Emanuel Goldberg and His Knowledge Machine: Information, Invention, and Political Forces (New Directions in Information Management) by Michael Buckland (Libraries Unlimited, (March 31, 2006)

- Otlet and Goldsmith were precursors as well

four figures in his research:

- Patrick Gattis - biologist, architect, diagrams of knowledge, metaphorical use of architecture; classification

- Paul Otlet, Brussels born

- Wilhelm Ostwalt - nobel prize in chemistry

- Otto Neurath, philosophher, designer of isotype

Paul Otlet

Otlet was interested in both the physical as well as the intangible aspects of the Mundaneum including as an idea, an institution, method, body of work, building, and as a network.<br />

(#t=1020)

Early iPhone diagram?!?

(roughly) armchair to do the things in the web of life

(Nelson quote) (get full quote and source for use)

(circa 19:30)

compares Otlet to TBL

Michael Buckland 1991 <s>internet of things</s> coinage

- did I hear this correctly? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_of_things lists different coinages

Turns out it was "information as thing"<br />

See: https://hypothes.is/a/kXIjaBaOEe2MEi8Fav6QsA

sugane brierre and otlet<br />

"everything can be in a document"<br />

importance of evidence

The idea of evidence implies a passiveness. For evidence to be useful then, one has to actively do something with it, use it for comparison or analysis with other facts, knowledge, or evidence for it to become useful.

transformation of sound into writing<br />

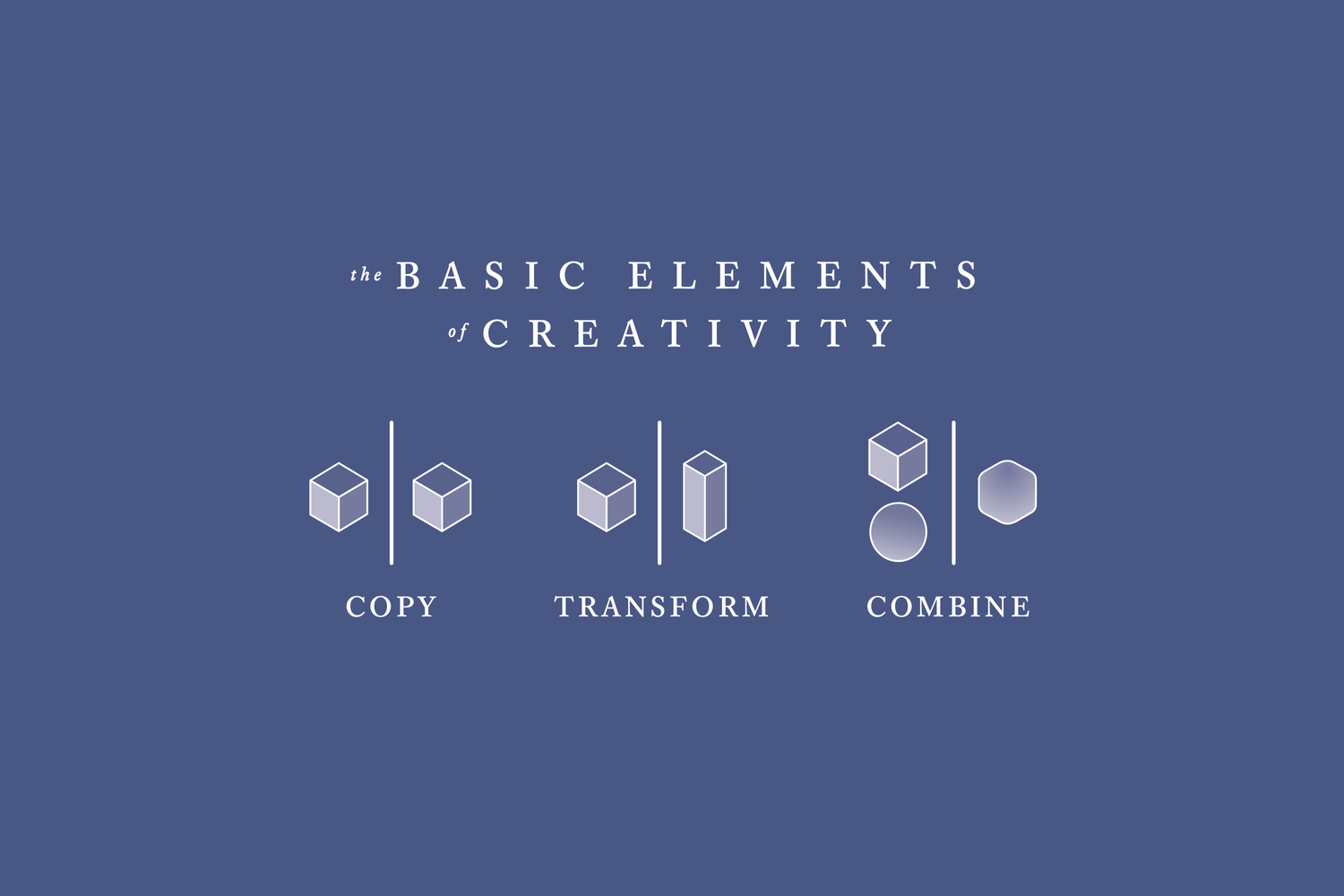

movement of pieces at will to create a new combination of facts - combinatorial creativity idea here. (circa 27:30 and again at 29:00)<br />

not just efficiency but improvement and purification of humanity

put things on system cards and put them into new orders<br />

breaking things down into smaller pieces, whether books or index cards....

Otlet doesn't use the word interfaces, but makes these with language and annotations that existed at the time. (32:00)

Otlet created diagrams and images to expand his ideas

Otlet used octagonal index cards to create extra edges to connect them together by topic. This created more complex trees of knowledge beyond the four sides of standard index cards.

(diagram referenced, but not contained in the lecture)

Otlet is interested in the "materialization of knowledge": how to transfer idea into an object. (How does this related to mnemonic devices for daily use? How does it relate to broader material culture?)

Otlet inspired by work of Herbert Spencer

space an time are forms of thought, I hold myself that they are forms of things.

(get full quote and source) from spencer

influence of Plato's forms here?

Otlet visualization of information (38:20)

S. R. Ranganathan may have had these ideas about visualization too

atomization of knowledge; atomist approach 19th century

examples:S. R. Ranganathan, Wilson, Otlet, Richardson,

(atomic notes are NOT new either...) (39:40)

Otlet creates interfaces to the world

- time with cyclic representation

- space

- moving cube along time and space axes as well as levels of detail

- comparison to Ted Nelson and zoomable screens even though Ted Nelson didn't have screens, but simulated them in paper

- globes

Katie Berner - semantic web; claims that reporting a scholarly result won't be a paper, but a nugget of information that links to other portions of the network of knowledge.<br />

(so not just one's own system, but the global commons system)

Mention of Open Annotation (Consortium) Collaboration:<br />

- Jane Hunter, University of Australia Brisbane & Queensland<br />

- Tim Cole, University of Urbana Champaign<br />

- Herbert Van de Sompel, Los Alamos National Laboratory annotations of various media<br />

see:<br />

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311366469_The_Open_Annotation_Collaboration_A_Data_Model_to_Support_Sharing_and_Interoperability_of_Scholarly_Annotations

- http://www.openannotation.org/spec/core/20130205/index.html

- http://www.openannotation.org/PhaseIII_Team.html

trust must be put into the system for it to work

coloration of the provenance of links goes back to Otlet (~52:00)

Creativity is the friction of the attention space at the moments when the structural blocks are grinding against one another the hardest.

—Randall Collins (1998) The sociology of philosophers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (p.76)