Private library: Schröder's dream<br /> by [[Benjamin Quaderer]] in DIE ZEIT<br /> accessed on 2026-01-25T15:02:05

- Jan 2026

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

reply to zk developer at https://reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/1qiwfp0/im_researching_why_zettelkasten_fails_for_a_lot/

Before you do this sort of user research, have you done the research on the dozens and dozens of apps that are already out there (prior art)? What do you think is good about them? Bad? Why are some doing well and others not?

You realize that at once a week since 2019, at least one app a week pops up in the zettelkasten, note taking, productivity/GTD space? Very, very few pass the 6 week mark, let alone the 6 month mark. Why do you want to reinvent the wheel? What are you hoping to get out of it?

Are you self-dogfooding/eating your own cooking? If you're not using and enjoying your own app, why would others?

Simply reading through this sub will give you most of the research and friction points you could want to know about without impinging on our time for something that I'd be willing to bet won't even reach alpha.

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

reply to harr at https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/3392/folgezettel-vs-duplex-numeric-arrangement

I'll shortly have a lot more to say on this very subtle historical subject, which I've been work at off and on over the past month or so. My analysis indicates entire lack of innovation on the fronts which you're indicating. Pages 178-180 show the period standard practice of the subject alphabetic filing you say Luhmann was innovating against, but the duplex-numeric is exactly what he was using. The method he chose had been recommended and in use since at least the 1910s—especially for law offices.

Your quotes from his 1981 paper, while interesting, create a false impression stemming from post hoc, ergo propter hoc analysis. You have to remember that by the 1980s, he's been practicing this for nearly 30 years and is providing a reflection on that practice, which is also heavily impacted by his systems theory work through those decades. I strongly suspect that his mid-century perspective didn't stray far from that Remington Rand outline or those of scores of other sources.

It bears noting that of the four potential methods suggested in the chapter, the last one is the Dewey Decimal method, which many who've been in the zettelkasten space have also very naturally tried using as a scaffolding for their filing work. Others have also reasonably suggested variations like the Universal Decimal Classification system or Wikipedia's Academic Outline of Disciplines.

One will also notice that the option of doing a "Variadex Alphabetic" arrangement hasn't ever (to my knowledge) been mentioned in the online zettelkasten space. It was given the pride of place as first in the list of options, but this stems primarily from the fact that it was a variation offered by Remington Rand as a paid product with the related accessories. Every filing cabinet company and major stationery company had variations on this theme with their own custom names and products.

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

Martin → chrisaldrich Yes, Chris, I even came across this site. Porstmanns Karteikunde was actually the publication that inspired my early Zettelkasten activities back when I was still a schoolboy, nearly half a century ago. And of course, Luhmann would have learned this kind of administrative practice in his first job, since it was widely used in offices at the time. I’ve always wondered whether he ever taught anything about it while working in Speyer.

Martin reports having used Porstmanns Karteikunde in his youth circa 1975 when it was widely used in offices.

Open question: Did Luhmann teach zettelkasten practices while at Speyer?

-

-

web.archive.org web.archive.org

-

Kuehn, Manfred. 2014. “Some Idiosyncratic Reflections on Note-Taking in General and ConnectedText in Particular.” ConnectedText - The Personal Wiki System. https://web.archive.org/web/20140215043743/http://www.connectedtext.com/manfred.php (January 3, 2026).

-

The number of scholars who have used the index card method is legion, especially in sociology and anthropology, but also in many other subjects. Claude Lévy-Strauss learned their use from Marcel Mauss and others, Roland Barthes used them, Charles Sanders Peirce relied on them, and William Van Orman Quine wrote his lectures on them, etc.

I'm pretty sure I've come across all these examples before, many from Kuehn in other contexts...

I HAVE read this before, but Hypothes.is isn't showing the matching document. See: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=url%3A%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.connectedtext.com%2Fmanfred.php%22

-

-

niklas-luhmann-archiv.de niklas-luhmann-archiv.de

-

Ms. 2906: Technik des Zettelkastens (1968), 'Vortrag' lecture (added by hand at the top left) #1968/01/13 by Niklas Luhmann in the [[Niklas Luhmann-Archiv]] on the method of ZK

via [[Chris Aldrich p]]

It talks about the methods of adding material and finding it (mentioned at the end) back. Not about using the material.

-

VII. Zum Schluss: aus persönlicher Erfahrung Andere arbeiten anders.

Ha! Personal experience: other people work differently. Never a truer word...

-

Wird bei grösserem Umfang problematisch werden.Mir reichen im grossen und ganzen zwei Hilfsmittel aus:1) alphabetisches Stichwortverzeichnis;2) Notizen auf den Literaturzetteln, falls das Problemüber den Namen hochkommt.

for bigger collections, finding of nots becomes harder. Luhmann thought two tools sufficient generally: 1) alphabetical index of terms, 2) finding note refs on literature notes if you start out from the name of a literature source. Digitally you have full text search ofc too. Not mentioned here, but in all cases I'd assume a 'walk' through the notes, folllowing the connections, will always ensue. The point I think is never finding 'a note' or 'the note' you have in mind, but 'finding notes' that are of use now. The title of the section also says it generally and in plural 'the finding of notes'

-

Daneben: Angaben über noch nicht gelesene Literaturzu bestimmten ThemenX in den Zettelkasten selbst anOrt und Stelle aufnehmen.X aus Anmerkungen in der gelesenen Literatur oder ausRezensionen, Verlagskatalogen usw.

Suggest to add references to unread literature directly in the ZK notes themselves (so not as a separate note in the bibliographic section). (I keep them in my bibliography section if they sound interesting to sometime acquire, clealry marked ofc).

-

Für Bücher, Zeitschriftenaufsätze, die Sie in derHand gehabt und bearbeitet haben, empfiehlt sich einbesonderer Bereich im Zettelkasten, vorne oder hinten,mit Zetteln über bibliographische Angaben. Ein Zettelpro Buch. Wichtig: Beschränkung auf selbst überprüf-te Angaben.Ermöglicht abgekürztes Zitieren auf den Zetteln.

Keep separate section of book index, books you have 'held in your hands and worked on', with bibliographic notes, one note per book. Cautions to only include bibliographic info you have verified yourself (presumably meant here is not to copy bibliographic references of sources, but follow the ref to the source to verify also the basic bibliographic info)

-

Überholtwerden unvermeidlich. Beweis eines Lernerfolgs.

nice. it is unavoidable that some notes will become obsolete / get surpassed. It is proof of a learning success.

This makes the volume of notes less a 'hoard' of knowledge, more a measure of the length of your learning journey?

-

Auch Vorlesungsmitschriften, Notizen über Gespräche,Einfälle bei allen möglichen Gelegenheiten können in denZettelkasten hinübergearbeitet werden

anything can be processed into the notes. reading, lectures, conversations, thoughts you had.

-

Kritisches Referieren ist zugleich eigene Gedankenarbeit,ist zugleich ein Lernprozess, ist zugleich ein Schlei-fen der eigenen Sprache.

critical referencing is 3 things at the same time: own thinking work, a learning process, and a way to hone your own language.

-

Wichtig: eigene Formulierungen versuchen. Das machteine strikte Trennung eigenen und fremden Gedankengutserforderlich.

try your own paraphrases, always needed to demarcate clearly between your own and other people's thinking

-

Trotzdem eine gewisse Groborientschematisierung für den An-fang wichtig. Erleichtert das Finden von "Gegenden".Woher?Literaturliste, Lehrbücher.Nochmals: das ist kein Kernproblem.

at the start of a ZK a first rough scheme of topics might be useful, but not a core problem to solve. It just helps in finding 'neighbourhoods' in your notes. Vgl [[Warning, Tacit Assumptions May Derail PKM Conversations]] wrt upfront cats or not.

-

Man muss unterscheiden zwischen themenspezifischenZettelsammlungen und Dauereinrichtungen für einStudium oder ein wissenschaftliches Lebenswerk.

interesting, as I see his ZKI as a more generic, and his ZKII as theme specific, yet ZKII is his life work and the more permanent set-up.

-

Luhmann, Niklas. 1968. “Ms. 2906: Technik des Zettelkastens.” Münster, Germany. Lecture Notes. https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/manuskripte/manuskript/MS_2906_0001 (January 2, 2026).

-

Finding the notes This will become problematic with larger volumes. For the most part, two tools suffice for me: 1) an alphabetical index; 2) notes on the bibliographical slips, in case the problem arises from the name.

-

In conclusion: from personal experience Others work differently.

-

Important: Try using your own wording. This requires a strict separation of your own and others' ideas Critical reporting is simultaneously one's own thought work, a learning process, and a refinement of one's own language.

-

Excerpts? Only if they are formal definitions or concise formulations. Do not copy pages and pages.

Luhmann encourages excerpts only for formal definitions and concise formulations. He explicitly admonishes against copy many pages outright.

-

Nevertheless, a certain rough orienting scheme is important for the beginning . It makes it easier to find "regions". Where from? Bibliography, textbooks. Again: this is not a core problem

Essentially my idea of creating "neighborhoods of ideas" explained in other terms.

-

Each note must have a fixed location that is never changed, as finding it depends on this. Remove it when needed and replace it exactly where it was placed This requires numbering the slips of paper. There will be long numbers, therefore alternating between numbers and letters for quicker recognition: 533/15 d 17 a 1

-

Paper slips (octavo) are perfectly sufficient, written on one side only

-

https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/manuskripte/manuskript/MS_2906_0001<br /> https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/manuskripte/manuskript/MS_2906_0004

Luhmann wrote his own zettelkasten method one pager back on Münster, January 13, 1968

Tags

- bibliography

- card index for learning

- zettelkasten

- neighborhoods of ideas

- definitions

- write only on one side

- zettelkasten numbering

- pkm

- ars excerpendi

- read

- Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten

- filing methods

- learning

- zettelkasten search

- writing as learning

- search

- coming to terms

- quotes

- subject filing

- ownership of ideas

- writing for understanding

- alphabetic filing systems

- zettelkasten method one pager

- Niklas Luhmann

- separating ideas

- 1968

- References

- zettelkasten are idiosyncratic

- connectivism

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

chatgpt, write me a summary of the zettelkasten method that is documented extensively online so i can post it to a sub full of people who have almost certainly heard of it before, but don't use the actual term

by u/andrewlonghofer at https://www.reddit.com/r/ObsidianMD/comments/1mbs3rd/technique_of_the_card_index_box_by_niklas_luhmann/

This is hilarious given that the article he's commenting on is a document written by Luhmann in 1968!

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

eaving the civil service in 1962, he lectured at the national Deutsche Hochschule für Verwaltungswissenschaften (University for Administrative Sciences) in Speyer, Germany.[6]

-

- Dec 2025

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CJDVBMCB <br /> Lockable Ammo Storage Case for Ammo Cans | Military Waterproof Case & Airtight Ammo Containers Box<br /> Used by Ray (via https://boffosocko.com/2023/11/06/index-card-cases-wallets-covers-pouches-etc/#comment-526182)

He's also using: DEWALT TOUGHSYSTEM 2.0 22 in. W Small Modular Tool Box<br /> https://www.homedepot.com/p/DEWALT-TOUGHSYSTEM-2-0-22-in-W-Small-Modular-Tool-Box-DWST08165/312134726

and DEWALT Toughsystem 2.0, 12.3 in. W Tool Box 3-Drawer<br /> https://www.homedepot.com/p/DEWALT-Toughsystem-2-0-12-3-in-W-Tool-Box-3-Drawer-DWST08330/324196375

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

How to Start a Zettelkasten When You Are Stuck in Theory • Zettelkasten Method<br /> by [[sascha]]<br /> accessed on 2025-12-11T14:08:33

Meh...

one of the shortest routes, but it also presumes a knowledge of too much other theory and is geared at getting one moving at creating rather than reading the theory

-

-

www.ernestchiang.com www.ernestchiang.com

-

Niklas Luhmann's Original Zettelkasten: Two Slip Boxes, Fixed Numbering, and Communication Partner<br /> by [[Ernest Chiang]]<br /> accessed on 2025-12-05T20:55:42

-

-

warburg.sas.ac.uk warburg.sas.ac.uk

-

Photo with at least 93 countable boxes visible...

-

Leszczyk, Marianna. 2025. “How Things Can Be Used: Aby Warburg’s Zettelkästen, Materiality, and Affordances.” The Warburg Institute. https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/news-events/blogs/how-things-can-be-used-aby-warburgs-zettelkasten-materiality-affordances (December 4, 2025).

-

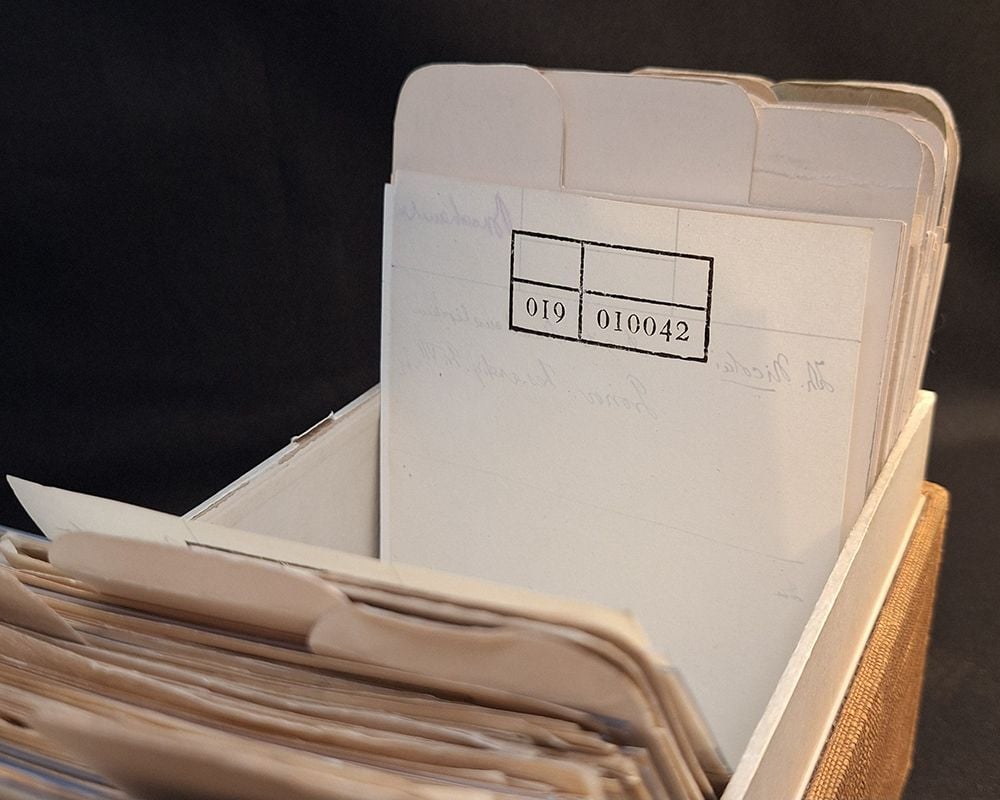

Fig. 3: View of selected dividers in ZK 19: “Religion – Myth”, “Mythology pragmatic”, “Venus and her entourage”, “Ancient Superstition Afterlife”, “Mysteries”. © Warburg Institute

Somewhat curious of the dates/times of the creation of these tabbed cards. Surely made in the 20th century, but since Warburg was likely creating notes in the late 1800s, where does this sit with respect to the invention of the tab card in 1894 claimed by Progressive Indexing and Filing (Remington Rand, 1950, p205)?

-

Fig.1: Selected Zettelkästen as stored at the Warburg Archive: ZK 17 “Politics” and ZK 7 “Iconology, Synthesis". © Warburg Institute

-

Fig. 2: Index card from ZK 19 displaying the numbering. © Warburg Institute

-

I would like to give the Zettelkästen a much larger online presence than they currently have, opening up new resonances between the digital gaze, the materiality of the archive, and the affordances of both.

😃

-

In a much cited anecdote by Fritz Saxl, Warburg’s long-term academic collaborator and first director of the Warburg Institute, we find Aby “standing tired and distressed, bent over his boxes with a packet of index cards, trying to find for each one the best place within the system”.[6]

[6] Fritz Saxl, The History of Warburg’s Library (1886-1944) cited in Gombrich 1970, p. 329; Marchand 2023, p. 186; Steiner 2013, p. 155; Wedepohl 2014, p. 389.

It's only in a physical card system one might worry a bit about "best place" for a card. Some of it is down to one's future self being able to find it, but cross-references could have been placed or an amanuensis might have created an exact copy for multiple copies in many locations.

What does Ernst Bernheim have to say on the topic of filing?

-

As Marchand elucidates, it was most likely before his research trip to Rome in autumn 1928 that Warburg had all the material in the then-existent 72 boxes stamped with a number sequence identifying each individual item by its box and its place within the order of items across all boxes (so, for instance, the index card shown in Fig. 2. would be item number 10042 in the overall sequence). This detailed indexing allowed Warburg and Gertrud Bing to assemble a new set of Zettelkästen specifically for the Rome trip without worrying about irredeemably displacing any items from their original locations. These “travelling boxes” were never dismantled as planned, however, and are still part of the Archive today, recognisable by a separate numbering sequence marked in square brackets (e.g. ZK [1]). Although the square-bracketed Zettelkasten sequence now also includes other boxes that were unnumbered at Warburg’s death, the visible difference between the two sequences remains a testimony to the mobility of the Zettelkasten corpus and its role in Warburg’s work on the famous Bilderatlas, a central part of which occurred during the abovementioned Rome trip with Bing.

"travelling boxes" as analog "back up"

-

The relative ease with which they could be relocated and transported allowed Warburg to use the Zettelkästen as a mobile research tool during periods of absence from his study. Indeed, even the characteristic numbering we now find on many of the paper slips is considered to be related to questions of travel.

direct evidence?

-

Aby Warburg left posterity with 99 index card boxes or, as they are called in German, Zettelkästen.

Tags

- Eckart Marchand

- Zettelkästen: Maschinen der Phantasie

- Aby Warburg's zettelkasten

- affordances

- Verknüpfungszwang

- Ariadne’s thread

- inventions

- zettelkasten

- travel

- Kulturwissenschaft

- zettelkasten numbering

- Gertrud Bing

- The Warburg Institute

- read

- Denkinstrumente (“thinking tools”)

- Library Bureau

- mobility

- Warburg Institute Archive

- personal knowledge management

- indexing systems

- Ernst Bernheim

- tools for thought

- tabbed dividers

- photos

- open questions

- index card dividers

- material culture

- Fritz Saxl

- References

Annotators

URL

-

-

Local file Local file

-

The next Complex method in order, is the Numeric,which may be divided into three classes, straight num-eric, duplex and decimal. It is safe to say that withthe straight Alphabetic or Geographic, ninety-five per-cent of the cases where an Index is used will be moreefficiently handled by the use of either one of theseMethods, than by the Numeric. However, there aresome cases where there is a great deal of cross refer-ence, thus making the use of the Numeric methodmore advantageous.

This is likely the reason why most commonplacers using index card systems use alphabetic set ups by subject rather than Niklas Luhmann's duplex numeric variation.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

The material filedcan be arranged as the cards would be,so as to bring together all the paperson a given subject.

-

is essential in subject work becausesome subjects are closely related andyet not sufficiently so to be filed to-gether.

The use of the cross reference sheet

A portion of the reason why Luhmann chose a duplex numeric filing system for his zettelkasten.

-

secondary number form of notation be considered in perfect order with-e. g.Administration :1-1-a General1-2-a Officers1-2-b Meetings of officers .This allows for more expansion and iscommonly termed "Duplex Numeric."

The numeric arrangement elim-inates the decimal feature and is used when the number of main divisions is likely to exceed nine, a primary and

This is exactly Niklas Luhamann's zettelkasten numbering system.

-

The object of any system is speedin service, and to obtain this, in sub-ject work, all correspondence on agiven subject must be filed together,regardless of who wrote it or at whattime it was written, so that the historyof everything that has taken place onone subject may be found in one place.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

ne of the chief drawbacks in using the Alpha-betic and Numeric systems in conjunction with asubject file is that in handling a large amount ofmaterial a great deal of cross referencing has tobe done, causing much extra labor and filling upthe files.

drawbacks of alphabetic and numeric systems with respect to cross referencing

-

If a letter refers to more than one subject, it isfiled under the name of the subject considered ofthe most importance, and a cross reference card ismade out and placed in the card index. The nameof the subject by which it is to be filed may beunderscored with a colored pencil.

Luhmann actively used red colored pencils in his cross referencing system, a practice that was suggested by many indexing and filing textbooks of his era.

-

utive numbers are assigned to the different sub-jects; if it is necessary to sub-divide these sub-jects, a letter of the alphabet is appended. Thus-Insurance..1 , Auto. Ins... 1-1 , Auto. Fire Ins.-1-1-a.

In the Numeric system of subject filing, consec-

-

-

Local file Local file

-

1002. By using the primary and secondary or duplexnumeric system (see §§ 159-163, 432-433) , the primary num-ber can be used to designate the client, each case or matterhandled for that particular client being indicated by thesecondary number, permitting the grouping of the records per-taining to a given client and his affairs in one place.

Luhmann would likely have been aware of duplex numeric systems of filing from legal and governmental filing work. It's not a difficult jump to go from client to subject matter to keep ideas bundled "in one place."

-

-

Local file Local file

-

division can be limited to 26. Although provision for a third subdi-vision can be made, it is not advisable.

The duplex numeric method of filing is designed for use when the number of primary or main subjects exceeds 10 and the second sub-

Specifically note the "is not advisable" portion, particularly with respect to N. Luhmann's practice.

-

- Nov 2025

-

www.wikiwand.com www.wikiwand.com

-

Das gerichtliche Aktenzeichen dient der Kennzeichnung eines Dokuments und geht auf die Aktenordnung (AktO) vom 28. November 1934 und ihre Vorgänger zurück.[4]

The court file number is used to identify a document and goes back to the file regulations (AktO) of November 28, 1934 and its predecessors.

The German "file number" (aktenzeichen) is a unique identification of a file, commonly used in their court system and predecessors as well as file numbers in public administration since at least 1934.

Niklas Luhmann studied law at the University of Freiburg from 1946 to 1949, when he obtained a law degree, before beginning a career in Lüneburg's public administration where he stayed in civil service until 1962. Given this fact, it's very likely that Luhmann had in-depth experience with these sorts of file numbers as location identifiers for files and documents.

We know these numbering methods in public administration date back to as early as Vienna, Austria in the 1770s.

The missing piece now is who/where did Luhmann learn his note taking and excerpting practice from? Alberto Cevolini argues that Niklas Luhmann was unaware of the prior tradition of excerpting, though note taking on index cards or slips had been commonplace in academic circles for quite some time and would have been reasonably commonplace during his student years.

Are there handbooks, guides, or manuals in the early 1900's that detail these sorts of note taking practices?

Perhaps something along the lines of Antonin Sertillanges’ book The Intellectual Life (1921) or Paul Chavigny's Organisation du travail intellectuel: recettes pratiques à l’usage des étudiants de toutes les facultés et de tous les travailleurs (in French) (Delagrave, 1918)?

Further recall that Bruno Winck has linked some of the note taking using index cards to legal studies to Roland Claude's 1961 text:

I checked Chavigny’s book on the BNF site. He insists on the use of index cards (‘fiches’), how to index them, one idea per card but not how to connect between the cards and allow navigation between them.

Mind that it’s written in 1919, in Strasbourg (my hometown) just one year after it returned to France. So between students who used this book and Luhmann in Freiburg it’s not far away. My mother taught me how to use cards for my studies back in 1977, I still have the book where she learn the method, as Law student in Strasbourg “Comment se documenter”, by Roland Claude, 1961. Page 25 describes a way to build secondary index to receive all cards relatives to a topic by their number. Still Luhmann system seems easier to maintain but very near.

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'> Scott P. Scheper </span> in Scott P. Scheper on Twitter: "The origins of the Zettelkasten's numeric-alpha card addresses seem to derive from Niklas Luhmann's early work as a legal clerk. The filing scheme used is called "Aktenzeichen" - See https://t.co/4mQklgSG5u. cc @ChrisAldrich" / Twitter (<time class='dt-published'>06/28/2022 11:29:18</time>)</cite></small>

Link to: - https://hypothes.is/a/Jlnn3IfSEey_-3uboxHsOA - https://hypothes.is/a/4jtT0FqsEeyXFzP-AuDIAA

-

-

www.ebay.com www.ebay.com

-

https://www.ebay.com/itm/127485195785

in the mid-20th century, Hedges Mfg. Co. made card index boxes

-

-

nagytimi85.github.io nagytimi85.github.io

-

https://nagytimi85.github.io/zettelkasten/zettels/<br /> Publicly browsable zettelkasten via github.io

-

- Oct 2025

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

I use the end-pa-pers at the back of the book to makea personal index of the author's pointsin the order of their appearance

The making of a personal index is a first step in building a mesh of knowledge. In just a few years, Vannevar Bush will speak of "associative trails" a phrase he uses twice in "As We May Think" (The Atlantic, July 1945), but of potentially more import is his phrase "associative indexing" which lays way to either juxtaposing or linking two ideas (either similar or disjoint) together. It bears asking the question of of whether it's more valuable to index and juxtapose similar ideas or disjoint ideas which may more frequently lead to better, more useful, and more relevant and rich future ideas.

It affords an immediate step, however, to associative indexing, the basic idea of which is a provision whereby any item may be caused at will to select immediately and automatically another. This is the essential feature of the memex. The process of tying two items together is the important thing. Bush, Vannevar. 1945. “As We May Think.” The Atlantic 176: 101–8. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/ (October 22, 2022). #

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

✍️ Systems I Use: Commonplace Book Zettelkasten

Someone who indicates that they use both "commonplace book" and "zettelkasten" systems. I'm curious how they differentiate the two, particularly because they seem to both be done on index cards.

Sort of sounds like zettles are her own ideas vs. commonplace for the ideas of others.

At 4:40 she seems to use linear numbering on her zettels and not Luhmann-artig numbering.

-

-

-

No. 113 New Feature! The ZIS: Zettelkasten Information Superhighway • Buttondown<br /> by [[Bob Doto]]<br /> accessed on 2025-10-06T16:40:32

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

https://www.reddit.com/r/PKMS/comments/1nst6fc/found_a_pkms_method_from_1916_that_im_shocked_i/

Office Appliances, August 1916 p115.

-

- Sep 2025

-

launch.getthinkable.com launch.getthinkable.com

-

https://launch.getthinkable.com/

Looks pretty, but in the end it won't be as highly functional as it looks pretty. I'd rather have a mahogany card index. Dollars to donuts this doesn't actually launch.

Reminiscent to Ugmonk's Analog System: https://ugmonk.com/collections/analog

-

- Aug 2025

-

writingslowly.com writingslowly.com

-

Use case for the Zettelkasten | Writing Slowly<br /> by [[Richard Griffiths]] <br /> accessed on 2025-08-30T23:59:42

-

-

smart-today-340107.framer.app smart-today-340107.framer.app

-

https://www.marginnote.com/<br /> Note taking application with audio recording

-

- Jul 2025

-

-

Why I Deleted My Second Brain: A Journey Back to Real Thinking<br /> by [[Westenberg]]

Meh... sounds like someone without any focus for an actual use case.... to each their own.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Melzi’s posthumousedition of the Treatise on Painting, for instance, would require collationfrom no fewer than eighteen notebooks.

-

Why did Leonardo not go to Venice to publish when Pacioli did? Had hetidied up the texts in his notebooks, he would have had no difficulty findinga patron and printer, and could have seen several books into print at thesame time as his friend.

Like many, da Vinci didn't publish much from his copious notebooks. He had huge volumes of material, but really not much to show for it in the end.

-

that of a centenarian who had died of arteriosclerosis

oops, Allen accidentally spills this note twice!

-

-

www.bankersbox.com www.bankersbox.com

-

Bankers Box, Liberty® Check and Form Boxes, String & Button, 4.25in x 6in with closeable lid

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

The four principles Niklas Luhmann used to build his notebox system are: Analog Numeric-alpha Tree Index The first letters of those four principles (A, N, T, I) are what comprise an Antinet. An Antinet Zettelkasten is a network of these four principles.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

I like to think of structure notes as a kind of wormhole from one "side" of the Zettelkasten to the other. If you're using the follower note approach, then your notes are already chained together in some way via the two-way links that are added to each note. So the primary function of a structure note is to let you jump directly from one chain of notes to another one that is very far away – there is little point in adding notes that are already close together in the sequence. Creating structure notes should feel like a creative exercise in compiling seemingly disparate ideas that actually have some hidden connection. Write each structure note like a table of contents for a small book about some very specific topic; if it's a book you actually want to read from one end to the other, then the structure note is successful. If writing the structure note feels feels like chore, then you're doing something wrong.

Nunca lo había pensado de esta manera. Mis notas de estructura suelen ser mini tablas de contenido de cosas relacionadas en lugar de disintas.

Me pregunto si algún enfoque algorítmico podría permitir visualizar esas conexiones extrañas entre nodos. He pensado en algo así para las etiquetas y otros elementos de organización de mi información.

-

The Zettelkasten: When there's something that I want to rediscover later, but forget about in the meantime, I add it to the Zettelkasten. This includes not only research notes and snippets of writing, but also ideas for future projects, interesting bookmarks and articles that I haven't yet read, and anything else that I want to find again but which isn't in itself critically important. To increase the chances of finding something again, try distributing it throughout the Zettelkasten – for example, instead of having a big list of bookmarks about some topic, sprinkle in a link here and there, where you might end up clicking on it again in the future when you stumble upon it.

De esta manera venía usando mi vieja instancia de TiddlyWiki (desde 2010) y también la nueva, (retomada en 2020) incluso antes de descubrir el Zettelkasten entre estas dos décadas.

El autor luego refiere dos herramientas para recordoar, una lista grande, inspirada en GTD y la bitácora diaria inspirada en el bullet journal. En mi caso, yo también usé TW para agendas y proyectos (es decir combinando GTD y actividades diarias), pero con el tiempo me decanté por Taskwarrior, porque estaba siempre convenientemente a la mano en mi ubicua y privada consola de comandos, en lugar de estar perdido en alguna de las desbordadas solapas del navegador, requiriendo autenticación y permisos y con el temor de que el estado de una nueva solapa sobreescribiera cosas importantes que tenía en la solapa ya abierta (en algún momento coloqué en MiniDocs una utilidad de agenda que se conectaba con Taskwarrior, llamada Acrobatask y le proveía una interfaz web, pero no avanzó mucho y quizás se integre mejor con Cardumem).

Ahora Taskwarrior en la consola se ocupa de los proyectos y los listados de tareas personales, mientras que para lo colectivo estoy probando NocoDB

-

Don't use a Zettelkasten to keep track of things Zettelkasten is designed for research and writing, not as an organizational system. In fact, I like to think of Zettelkasten as a kind of "tool for forgetting". You can use the Zettelkasten to think through complex problems in a structured way, completely forget about everything you just wrote down, and then wait for the Zettelkasten to bring those ideas up to you again, as though it were a kind of conversation partner. Later, the individual notes can be stictched together into a larger publishable piece.

-

The result of this is that a note can be renamed without changing its filename and without updating existing links to that file. You can also use special characters in titles without any issues. As for why this actually matters, well, it's mostly a matter of aesthetics. A Zettelkasten is supposed to be a simple system for building knowledge out of small notes in an organic way. The simplest possible Zettelkasten is implemented in terms of slips of paper which are assigned identifiers for linking between them. In a digital system, the most straight-forward emulation of such a system is with files whose filenames are unique IDs, and links that are simply the IDs themselves. Many note-taking applications assume a model that is fundamentally incompatible with such an approach, usually because they conflate titles with filenames (as Denote and zk.el do), or even with IDs, as Obsidian does! zt, in contrast, takes these simple, plain-text foundations as its base, and then adds extra digital-only functionality on top to make it an actually useful system.

Me enfrenté a la duda sobre los identificadores únicos para documentos en Grafoscopio y finalmente opté por NanoID, debido a la baja posibilidad de colisión con tan sólo 11 caracteres, lo que es más corto que una fecha única (pues hay que capturar los milisegundos para hacer un indicador único), funciona incluso cuando se producen muchos trozos de información rápidamente (por ejemplo en una importación de información donde hasta los milisegundos podrían coincidir) y, de todos modos, la fecha es un metadato que se puede capturar en otro lado y por alguna razón para mí no es tan memorable. Si bien el NanoID es un indicador no memorable, los videos en YouTube se hacen virales por otros datos (como su título/autor o los algoritmos de recomendación) y no por la memorabilidad de su enlace (todos acá son no memorables).

Para lidiar con la memorabilidad y organización para humanos, el identificador único es un sufijo en lugar de un prefijo, que va al final del nombre del archivo, separado por doble guiones y antes de la extensión, por ejemplo,

cartofonias--e45j7.md.html). Dado que los navegadores web recuerdan partes del enlace, incluso si el nombre se cambiara, pero recordáramos (en parte) el identificador único (en e ejemploe45j7), nos sugeriría diferentes títulos que incluyen esa secuencia de caracteres.

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

There are emergent structures that underly every self-organizing body of knowledge. Software that helps you deal with these structures needs to fulfill a couple of criteria for its ability to handle complex structures. One criterion is: Does the software provide access to those different structural layers? If it doesn’t offer the means to deal with those structures, it won’t help you in your work once your archive becomes more complex.

-

Take Wikis as an example. Most of them have two different modes: The reading mode. The editing mode. The reading mode is the default. But most of the time you should create, edit and re-edit the content. This default, this separation of reading and editing, is a small but significant barrier on producing content. You will behave differently. This is one reason I don’t like wikis for knowledge work. They are clumsy and work better for different purposes.

Los blikis (blogs + wikis) son formas de pensar en público y tener modos de lectura y escritura está bien, pues no todos los que se aproximan al wiki lo van a editar y la mayoría de internautas sólo lo va leer.

Además sistemas tipo TiddlyWiki (y en el futuro Cardumem) alientan en buena medida la reedición de unidades de contenido (wiki refactoring). Lo clave es que las unidades sean pequeñas y se puedan usar para organizar otras unidades (es decir usarlos como etiquetas).

-

-

brianrytel.com brianrytel.com

-

Card Files and Alternatives for Zettelkasten, Index, etc – Brian Rytel by [[Brian Rytel]]

Mostly a rehash of my list, but one or two alternates.

-

-

www.soenkeahrens.de www.soenkeahrens.de

- Jun 2025

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

- May 2025

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

The Screenless Writer by [[Steven Budden Jr.]] (aka Classic Typewriter)

"My screenless computer, which is a box of these [handmade] cards. The NEXUS which stands for Network of EXperiences Synchronicities and UnderStanding." —Steven Budden, Jr.

-

- Mar 2025

-

writingslowly.com writingslowly.com

-

Aby Warburg's Zettelkasten and the search for interconnection by [[Richard Griffiths]]

-

-

Local file Local file()1

-

[T]he titles noted down were those which had aroused Warburg’s scholarly curios-ity while he was engaged on a piece of research. They were all interconnected in apersonal way as the bibliographical sum total of his own activity. These lists were,therefore, his guide as a librarian ; not that he consulted them every time he readbooksellers’ and publishers’ catalogues ; they had become part of his system and schol-arly existence. [...] Often one saw Warburg standing tired and distressed bent over hisboxes with a packet of index cards, trying to ind for each one the best place withinthe system ; it looked like a waste of energy. [...] It took some time to realise that hisaim was not bibliographical. This was his method of deining the limits and contentsof his scholarly world and the experience gained here became decisive in selectingbooks for the Library. 5

via Fritz Saxl, The History of Warburg’s Library (1943/1944), p. 329.

Where does the work reside? Goes to the idea of zettelkasten coherence.

-

-

www.linkedin.com www.linkedin.com

-

Reply to Gertina Blanket on LinkedIn:

Jij legt in één klap uit datgene wat ik nooit goed heb begrepen uit de literatuur... Het verschil tussen interleaving en varied practice (die vaak als hetzelfde worden gebruikt in de "volksmond").

Het een gaat over verschillende hoeken kijken naar hetzelfde idee (varied practice) terwijl het ander gaat over verschillende maar soortgelijke ideëen (interleaving), bijvoorbeeld meerdere soorten wiskunde (algebra, trigonometrie, etc.).

Hierbij wil ik uiteraard wel zeggen dat blocked practice niet per se direct toegepast moet worden als het over automatisering gaat -- de cognitieve schemata moeten eerst goed gevormd zijn. Zie ook 4C/ID (Ten Steps to Complex Learning). Ofwel, eerst goede encoding + retrieval (Spaced Interleaved Retrieval, mindmapping, etc.) en dan focus op "drilling" / knowledge fluency.

Het sneller maken / automatiseren heeft geen enkel nut als het begrip er nog niet goed in zit. Dit moet geverifiëerd worden.

Kennis is natuurlijk ook erg interdisciplinair. Ik wordt er extreem blij van als ik een link leg tussen een boek over filosofie en efficiënt leren/onderwijs bijvoorbeeld.

Zo las ik ooit een boek over romeinse oratoren met een misleidende titel "How to Win an Argument" van Marcus Tullius Cicero, vertaald door James M. May, en hierin kwam ik tegen dat de oude Romeinen al door hadden dat LOGICA is wat het brein doet onthouden, en dit hoeft dus geen objective logica te zijn maar meer een correcte reflectie van hoe je eigen geest werkt en verbanden legt.

Dit is direct in lijn met wat ik weet van cognitieve leerpsychologie en mijn klein beetje kennis van neurowetenschap (waar ik dit jaar dieper in wil duiken).

Informatie in isolatie is nooit stevig, het moet zich vastklampen aan ankers en andere kennis (voorkennis eventueel), en de lerende (niet de onderwijzende) moet actief bezig zijn om deze verbanden te leggen.

Zoals ik wel vaker quote van Dr. Sönke Ahrens: "The one who does the effort does the learning."

Als ik een boek lees denk ik automatisch aan hoe ik dit kan relateren aan wat al in mijn second mind (Zettelkasten) zit. Ik denk niet meer linear, alleen maar non-linear. Standaard in verbanden.

Hier wat bronnen (impliciet) genoemd: - Cicero, M. T. (2016). How to win an argument: An ancient guide to the art of persuasion (J. M. May, Trans.). Princeton University Press. - Ahrens, S. (2017). How to take smart notes: One simple technique to boost writing, learning and thinking: for students, academics and nonfiction book writers. CreateSpace. - fast, sascha. (100 C.E., 45:02). English Translation of All Notes on Zettelkasten by Luhmann. Zettelkasten Method. https://zettelkasten.de/posts/luhmanns-zettel-translated/ - Luhmann, N. (1981a). Communicating with Slip Boxes (M. Kuehn, Trans.). 11. - Luhmann, N. (1981b). Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen. In H. Baier, H. M. Kepplinger, & K. Reumann (Eds.), Öffentliche Meinung und sozialer Wandel / Public Opinion and Social Change (pp. 222–228). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-87749-9_19 - Moeller, H.-G. (2012). The radical Luhmann. Columbia University Press. - Scheper, S. (2022). Antinet Zettelkasten: A Knowledge System That Will Turn You Into a Prolific Reader, Researcher and Writer. Greenlamp, LLC.

- Schmidt, J. F. K. (2016). Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine. In Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe (pp. 287–311). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004325258_014

- Schmidt, J. F. K. (2018). Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: The Fabrication of Serendipity. Sociologica, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/8350

Tags

- Reply

- Interleaving

- Education

- James M. May

- Zettelkasten

- Intellectualism

- Schema Automation

- Retrieval

- Knowledge Work

- Teaching

- 4C/ID

- Antinet

- Learning

- Schema Formation

- Gertina Blanket

- Encoding

- Niklas Luhmann

- Spaced Interleaved Retrieval

- Varied Practice vs. Interleaving

- Marcus Tullius Cicero

- Interdisciplinary Knowledge

- Ten Steps to Complex Learning

- Varied Practice

Annotators

URL

-

- Feb 2025

-

srsergiorodriguez.github.io srsergiorodriguez.github.io

-

Me aproximo a la escritura como investigación como lo elabora Laurel Richardson, es decir, desarrollando procesos analíticos en la medida en la que se escribe y se encuentran posibles caminos de indagación20Laurel Richardson y Elizabeth Adams St. Pierre, «Writing: A Method of Inquiry», The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, ed. Norman K. Denzin y Yvonna S. Lincoln (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2018).. Estos caminos pueden abrir encuentros fortuitos, coincidencias, ideas inesperadas que, junto a los datos, se integran a la narrativa general y la argumentación. El método cualitativo de la Zettelkasten, comentado antes, es en definitiva el insumo del que finalmente se nutre la escritura. Como afirma Richardson, la escritura como investigación toma de muchos géneros textuales y se nutre de múltiples voces para configurar un proceso de cristalización más que de triangulación.

-

de forma similar al método de teoría fundamentada permite encontrar patrones comunes en las fuentes consultadas

-

Zettelkasten4

-

-

writing.bobdoto.computer writing.bobdoto.computer

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Maybe it's because I have posted here before, reddit keeps recommending this forum to me when I log in, and I'm immensely frustrated by the posts asking questions about "the Zettlekasten method" and the responses. Why? Because folks are talking about different things all the time. It's like chickens taking to ducks. From my observation, people define "the Zettlekasten method" at least in two ways: (1) A paper or digital index card note system organized by folders, tags, links, tables of contents. (I don't think it's fair to give it a German name as its use can at least be dated in various cultures since the middle ages. Maybe the book authors and influencers want to lure people to think, fancy name=magic bullet?) (2) A note system "based on the principles and practices of Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten method," as the sidebar of this forum describes. These are different concepts! (2) is a special case of (1). Anything you agree or disagree is meaningless if one of you is talking about (1) and the other is talking about (2). So what is this forum about, (1) or (2)? When you say you are attracted by "the Zettlekasten method," do you mean (1) or (2)? I don't think many people disagree with you if you mean Definition (1). Why you talk about "my zettelkasten," if you maintain a genetic index card system, you are not doing Zettlekasten in the Luhmann sense. At least, when you post, whether OP or as response, please specify which definition you are using, 1, 2, or 3, 4.

reply to u/Active-Teach6311 at https://old.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/1ilvvnc/you_need_to_first_define_the_zettlekasten_methoda/

#1 == #2 In German contexts, zettelkasten subsumed both ideas which can easily be seen in the 2013 Marbach Exhibition: Zettelkasten: Machines of Fantasy. That exhibition featured six different Zettelkasten of which Luhmann's was but one. It wasn't until after this that sites like zettelkasten.de, this Reddit sub, or the popularity of Ahrens' book shifted the definition to a Luhmann-centric one, particularly in English language contexts which lacked a marketing term on which to latch to sell the idea. The productivity porn portion of the equation assisted in erasing the prior art and popularity of these methods.

One can easily show mathematically that there is a one-to-one and onto mapping of Luhmann's method with all the other variations. This means that they're equivalent in structure and only differ in the names you give them.

Even Ahrens suggests as much in his own book when he mentions that in digital contexts one doesn't need numbered cards in particular orders for the system to work. If Erasmus, Agricola, or Melanchthon were to magically arrive from the 15th century to the present day, they would have no difficulty recognizing their commonplacing work at play in a so-called Luhmann-artig zettelkasten.

I would suggest that Luhmann didn't write more about his method himself because it would have been generally fruitless for him as everyone around him was doing exactly the same thing. The method was both literally and figuratively commonplace! J. E. Heyde's book, from which Luhmann modeled his own system, went through 10 editions from the 1930s through the 1970s in Luhmann's own lifetime.

-

This suffers from a sufficient formalisation of the concept of "similarity". Everything is either so similar that characterisation as "identical", similar or different or very different, depending on the frame of reference. By pointing out some resemblense, you cannot make a justified judgement about the similarity or difference of anything. I would suggest that Luhmann didn't write more about his method himself because it would have been generally fruitless for him as everyone around him was doing exactly the same thing. I asked ca. two dozen professors at the very university about their method (btw. at the very university that Luhmann was a professor at). NONE had anything remotely resembling a Luhmann-Zettelkasten. During his lifetime there was quite some interest in his Zettelkasten, hence the visitors, hence the disappointment of the visitors (people made an effort to review his Zettelkasten): (9/8,3) Geist im Kasten? Zuschauer kommen. Sie bekommen alles zu sehen, und nichts als das – wie beim Pornofilm. Und entsprechend ist die Enttäuschung. - From his own Zettelkasten So: The statement that his practice was basically common place (or even a common place book) is not based on sound reasoning (sufficiently precise in the use of the concept "similarity") There is empirical evidence that it was very uncommon. (Which is obvious if you think about the his theoretical reasoning about his Zettelkasten as heavily informed by the very systems theory that he developed. So, a reasoning unique to him)

Reply to u/FastSascha at https://old.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/1ilvvnc/you_need_to_first_define_the_zettlekasten_methoda/mc01tsr/

The primary and really only "innovation" for Luhmann's system was his numbering and filing scheme (which he most likely borrowed and adapted from prior sources). His particular scheme only serves to provide specific addresses for finding his notes. Regardless of doing this explicitly, everyone's notes have a physical address and can be cross referenced or linked in any variety of ways. In John Locke's commonplacing method of 1685/1706 he provided an alternate (but equivalent method) of addressing and allowing the finding of notes. Whether you address them specifically or not doesn't change their shape, only the speed by which they may be found. This may shift an affordance of using such a system, but it is invariant from the form of the system. What I'm saying is that the form and shape of Luhmann's notes is identical to the huge swath of prior art within intellectual history. He was not doing something astoundingly new or different. By analogy he was making the same Acheulean hand axe everyone else was making; it's not as if he figured out a way to lash his axe to a stick and then subsequently threw it to invent the spear.

When I say the method was commonplace at the time, I mean that a broad variety of people used it for similar reasons, for similar outputs, and in incredibly similar methods. You can find a large number of treatises on how to do these methods over time and space, see a variety of examples I've collected in Zotero which I've mentioned several times in the past. Perhaps other German professors weren't using the method(s) as they were slowly dying out over the latter half of the 20th century with the rise and ultimate ubiquity of computers which replaced many of these methods. I'll bet that if probed more deeply they were all doing something and the something they were doing (likely less efficiently and involving less physically evident means) could be seen to be equivalent to Luhmann's.

This also doesn't mean that these methods weren't actively used in a variety of equivalent forms by people as diverse as Aristotle, Cicero, Quintilian, Seneca, Boethius, Thomas Aquinas, Desiderius Erasmus, Rodolphus Agricola, Philip Melancthon, Konrad Gessner, John Locke, Carl Linnaeus, Thomas Harrison, Vincentius Placcius, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, S. D. Goitein, Gotthard Deutsch, Beatrice Webb, Sir James Murray, Marcel Mauss, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Mortimer J. Adler, Niklas Luhmann, Roland Barthes, Umberto Eco, Jacques Barzun, Vladimir Nabokov, George Carlin, Twyla Tharp, Gertrud Bauer, and even Eminem to name but a few better known examples. If you need additional examples to look at, try searching my Hypothesis account for tag:"zettelkasten examples". Take a look at their examples and come back to me and tell me that beyond the idiosyncrasies of their individual use that they weren't all doing the same thing in roughly the same ways and for roughly the same purposes. While the modalities (digital or analog) and substrates (notebooks, slips, pen, pencil, electrons on silicon, other) may have differed, the thing they were doing and the forms it took are all equivalent.

Beyond this, the only thing really unique about Luhmann's notes were that he made them on subjects that he had an interest, the same way that your notes are different from mine. But broadly speaking, they all have the same sort of form, function, and general topology.

If these general methods were so uncommon, how is it that all the manuals on note taking are all so incredibly similar in their prescriptions? How is it that Marbach can do an exhibition in 2013 featuring 6 different zettelkasten, all ostensibly different, but all very much the same?

Perhaps the easier way to see it all is to call them indexed databases. Yours touches on your fiction, exercise, and nutrition; Luhmann's focuses on sociology and systems theory; mine looks at intellectual history, information theory, evolution, and mathematics; W. K. Kellogg's 640 drawer system in 1906 focused on manufacturing, distributing and selling Corn Flakes; Jonathan Edwards' focused on Christianity. They all have different contents, but at the end of the day, they're just indexed databases with the same forms and functionalities. Their time periods, modalities, substrates, and efficiencies have differed, but at their core they're all far more similar in structure than they are different.

Perhaps one day, I'll write a deeper treatise with specific definitions and clearer arguments laying out the entire thing, but in the erstwhile, anyone saying that Luhmann's instantiation is somehow more unique than all the others beyond the meaning expressed by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in The Little Prince is fooling themselves. Instead, I suspect that by realizing you're part of a longer, tried-and-true tradition, your own practice will be far easier and more useful.

The simplicity of the system (or these multiply-named methods) allows for the rise of a tremendous amount of complexity. This resultant complexity can in turn hide the simplicity of the root system.

“To me, you are still nothing more than a little boy who is just like a hundred thousand other little boys. And I have no need of you. And you, on your part, have no need of me. To you, I am nothing more than a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes. But if you tame me, then we shall need each other. To me, you will be unique in all the world. To you, I shall be unique in all the world..."

I can only hope people choose to tame more than Luhmann.

-

"#1 == #2" If this were true, everyone here, or their predecessors debating and advocating one note system over others (e.g., Sertillanges, Ahrens) have all been wasting their time. LOL. Sharing similar principles doesn't make the systems identical.

reply to u/Active-Teach6311 at https://old.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/1ilvvnc/you_need_to_first_define_the_zettlekasten_methoda/mc14p0r/

Certainly there are idiosyncracies in how each person chooses to to work with them. The primary difference I see is how much work and when each person chooses to put into a system and what outputs, if any, there are. However, at the end of the day, their similarities as systems far, far exceed their differences. Their principles may differ in slight ways, but in the end they are identical in form. If you feel differently, then I suggest you take a deeper and closer look into the variety of traditions beyond your cursory view.

As a small exercise, attempt to explain why S. D. Goitein's system allowed him to write 1/3 the notes of Luhmann and create almost 3 times the written output? Why aren't people emulating his system? Why are there still dozens of researchers actively sharing and using Goitein's notes when almost none are doing the same for Luhmann?

Another solid exercise is to look at Heyde and explain why Luhmann chose to file his cards differently than was prescribed there? Are the end results really different? Would they have been different if kept in commonplace form using John Locke's indexing method?

-

Explain your definition of hierarchical reference system. How is one note in his system higher, better, or more important than another? Where do you see hierarchies? Lets say Luhmann were doing something on bread. First off he has 3 notes and these end up sequenced 1,2,3. Then he does the equivelent of a block link on 1 by creating 1a=banana bread, 1b=flour bread. A good discussion (https://yannherklotz.com/zettelkasten/) If there weren't direct mappings, it should be impossible to copy & paste Luhmann's notes into Obsidian, Logseq, OneNote, Evernote, Excel, or even Wikipedia. That's not true at all. One can dump from one structure into another structure you just potentially lose structure in the mapping. Those systems don't have similar capabilities. Obsidian has folders Logseq does not. Logseq has block level linking Obsidian does not. I can't even reliable map between the first two elements of your list. Now we throw in OneNote that directly takes OLE embeds which means information linked can dynamically change after being embedded. That is say I'm tracking "current BLS inflation data" it will remain permanently current in my note. Neither Obsidian nor Logseq support that. Etc.. Excel, OneNote and Logseq allow for computations in the note (i.e. the note can contain information not directly entered) Obsidian and Wikipedia do not. We might argue about efficiencies, affordances, or speed, but at the end of the day they're all still structurally similar. We are totally disagreeing here. The OLE example being the clearest cut example.

reply to u/JeffB1517 at https://old.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/1ilvvnc/you_need_to_first_define_the_zettlekasten_methoda/mc1y4oj/

I'm not new here: https://boffosocko.com/research/zettelkasten-commonplace-books-and-note-taking-collection/

You example of a hierarchy was not a definition. In practice Luhmann eschewed hierarchies, though one could easily modify his system to create them. This has been covered ad nauseam here in conversations on top-down and bottom-up thinking.

When "dumping" from one program to another, one can almost always easily get around a variety of affordances supplied by one and not another simply by adding additional data, text, references, links, etc. As an example, my paper system can do Logseq's block level linking by simply writing a card address down and specifying word 7, sentence 3, paragraph 4, etc. One can also do this in Obsidian in a variety of other technical means and syntaxes including embedding notes. Block level linking is a nice affordance when available but can be handled in a variety of different (and structurally similar) ways. Books as a technology have been doing block level linking for centuries; in that context it's called footnotes. In more specialized and frequently referenced settings like scholarship on Plato there is Stephanus pagination or chapter and verse numberings in biblical studies. Roam and Logseq aren't really innovating here.

Similarly your OLE example is a clever and useful affordance, but could be gotten around by providing an equation that is carried out by hand and done each time it's needed---sure it may take more time, but it's doable in every system. This may actually be useful in some contexts as then one would have the time sequences captured and logged in their files for later analysis and display. These affordances are things which may make things easier and simpler in some cases, but they generally don't change the root structure of what is happening. Digital search is an example of a great affordance, except in cases when it returns thousands of hits which then need to be subsequentlly searched. Short indexing methods with pen and paper can be done more quickly in some cases to do the same search because one's notes can provide a lot of other contextual clues (colored cards, wear on cards, physical location of cards, etc.) that a pure digital search does not. I often can do manual searches through 30,000 index cards more quickly and accurately than I can through an equivalent number of digital notes.

There is a structural equivalence between folders and tags/links in many programs. This is more easily seen in digital contexts where a folder can be programatically generated by executing a search on a string or tag which then results in a "folder" of results. These searches are a quick affordance versus actively maintaining explicit folders otherwise, but the same result could be had even in pen and paper contexts with careful indexing and manual searches (which may just take longer, but it doesn't mean that they can't be done.) Edge-notched cards were heavily used in the mid-20th century to great effect for doing these sorts of searches.

When people here are asking or talking about a variety of note taking programs, the answer almost always boils down to which one you like best because, in large part, a zettlkasten can be implemented in all of them. Some may just take more work and effort or provide fewer shortcuts or affordances.

-

don't think they map. For example Luhmann is fundamentally maintaining a hierarchical reference system since note length is fixed. With digital infinitely long individual notes that aspect drops out. We use a graph database today, Luhmann was keeping a very limited relational system. Backlink tracking is fundamental to Luhmann, it is automated today so no tracking. Put that together and you get multiple overlapping subject hierarchies, for example MOCs and whiteboard with the same notes organized differently, Luhmann didn't allow for this. A computer can index 100k notes in a few seconds. Luhmann would have lost a month of full-time work redoing an index. Yes I think these systems are similar. Someone who gets Obsidian gets Logseq. But what is actually being done differs.

reply to u/JeffB1517 at https://old.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/1ilvvnc/you_need_to_first_define_the_zettlekasten_methoda/mc0f8ip/

Explain your definition of hierarchical reference system. How is one note in his system higher, better, or more important than another? Where do you see hierarchies?

Infinitely long notes can easily be excerpted down to smaller sizes and filed, so that portion of your argument doesn't track.

Luhmann had what some call "hub notes" and the ability to remove cards and rearrange them to suit his compositional needs and later refile them. This directly emulates the similar ideas of MOCs, whiteboards, and mind maps. Victor Margolin's example quickly shows how this is done in practice.

If there weren't direct mappings, it should be impossible to copy & paste Luhmann's notes into Obsidian, Logseq, OneNote, Evernote, Excel, or even Wikipedia. This is not the case. You might get slightly different personal affordances out of these tools or perhaps better speed and in other cases even less speed or worse review patterns of your notes, but in ultimate form they are identical and will ultimately allow you to accomplish all of the same end results.

We might argue about efficiencies, affordances, or speed, but at the end of the day they're all still structurally similar.

-

-

yannherklotz.com yannherklotz.com

-

Introduction to Luhmann's Zettelkasten by [[Yann Herklotz]]

-

-

harpers.org harpers.org

-

Illustration by Beppe Giacobbe

Illustration by Beppe GiacobbeHarper's Magazine, April 2022, page 26 https://harpers.org/archive/2022/04/

-

- Dec 2024

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

All these "rules" are really just guidance/suggestions... I highly recommend you try out the thing you would imagine to work and see how it goes. If it works for you, then great. If not, try something else. What works for someone else isn't necessarily going to work for you. How do you think these things came about? They really weren't invented, but slight variations on a pre-existing theme that someone customized for their needs.

It's called a "zettelkasten practice" for a reason. After you've been at it for a few months, write up your experience and let us know how it all worked out. What worked well? What didn't? Speculate on the reasons why...

reply to u/King_PenguinOs at https://old.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/1hklaii/getting_started_with_zettelkasten/

-

-

Local file Local file

-

The photo celebratedthe making of the Syntopicon. This massive index of Western thought,which in conception had grown godlike out of the head of MortimerAdler, was intended to help readers navigate their way through theGreat Books.

Interesting that he reduces hundreds of thousands of hours of work to "grown godlike out of the head of Mortimer Adler..."

-

-

www.metalcabinetliquidators.com www.metalcabinetliquidators.com

-

https://www.metalcabinetliquidators.com/ Rancho Cucamonga, CA<br /> James

-

-

www.mycelium-of-knowledge.org www.mycelium-of-knowledge.org

-

https://www.mycelium-of-knowledge.org/<br /> Dr. Rupert Rebentisch, Bad Vilbel Germany,<br /> rupert.rebentisch.at.gmail.com

If you were going to start a blog about zettelkasten as a sales funnel....

Circling back around, I notice he mentions Matt Giaro who teaches marketing and conversion online: https://mattgiaro.com/

-

-

writing.bobdoto.computer writing.bobdoto.computer

-

Reinforces the communal nature of knowledge workAll ideas are in communication with and informed by others, regardless of whether we work in direct collaboration with others. A collaborative zettelkasten not only shows this in real time, but allows participants to actively engage with a collective web of insight.

This is key imo. The link between personal knowledge and communal K. In context of TGL it also means fleshing out the purpose, identity and intent of our work. A step to and in support of [[Networked Agency 20160818213155]] , here the functioning as a company Can I express this to the team?

This is a benefit that Doto does not express (because he stays within the context of ZK, and this one becomes apparent if you look at the ZK in the context of the group of collab. Any non-random and pre-existing group will find theur benefit in that context, rather than in the instrument's built-in affordances. tech+issue=value.

-

Working with the Collaborative Network of Ideas

For me the purpose of a collab zk would need to be aligned to what drives the collaborators. E.g. how I tie pkm to individual professional activism and autonomy, and extended/aggregated to teamkm it drives the core value of constructive activism of my company, and how we use [[Systems convening denken Wenger Trayner 20230914131102]] to translate that into interventions and desirable client projects. Vgl [[PKM systems convening activisme relatie 20241123085857]] expressing that connection.

-

Participants may or may not have a common output, goal, or project in mind when they start. The only requirements are: all participants add to the collection of main notes all participants establish connections between ideas all participants are free to pull from the zettelkasten for their writing projects

This describes a wiki too. What difference? Wiki tends to follow the Wikipedia model perhaps, aiming for completeness / definitive state? Wikipedia is not atomic in the ZK sense. Also public wiki's (the ones one is by def aware of) are an output themselves. My internal wiki 2004-2012 was much more atomic and not an output but an instrument. So if wiki then more of the instrument style, iow ZK by another name. A collective network of meaning and sense making

-

- Nov 2024

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

I'm reminded of poor online friend Jack Baty who can never seem to settle on a PKM approach, oscillating between 5 or so over the years, including publishing platforms/blogs. It's easy to reply "Don't! There's no greener grass on any side." But that also misses the point, I believe, when in the end one just wants to explore and tinker. And not get stuff done all the time. All that being said, I believe there's hope in simplicity of a Zettelkasten, but maybe that's not what is being searched for 😅

via [[Christian Tietze]] at https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/comment/22076/#Comment_22076

There's tremendous value in keeping a single zettelkasten store of knowledge. Spreading it out only dilutes things and can prevent building. Shiny object syndrome can be a problem as it's often splitting the stores of information and silo-ing them from each other. Unless the shiny object can do something radically different or has a dramatic affordance it's really only a distraction.

But still, sometime the search for either simpler or better serves other needs...

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

Cal Newport vs Zettelkasten – SAD! (Clickbait) by [[Sascha Fast]] on 2024-11-28

-

The inner map that you develop through the Zettelkasten, on the other hand, is directly linked to the knowledge structures themselves.

This sounds a lot like Peter Ramus in the late 1500s with respect to educational reform.

He's sidelining the usefulness of mnemonic techniques in lieu of something he values more, potentially without having a full appreciation of the former.

-

The difference between what you work out using the Zettelkasten and the memory palace technique is that the memory palace is a pure memory technique. It uses meaningless connections and the way the brain works to gain access to information. For example, if I mentally write the date Rome was founded with the mnemonic “BC 753 Rome came to be” as a number on an egg in the kitchen fridge, the only reason for this link between the egg in the kitchen fridge of my memory palace and the year Rome was founded is that I can remember this number. You make yourself aware of what the brain otherwise does unconsciously.

The difference between what you work out using the Zettelkasten and the memory palace technique is that the memory palace is a pure memory technique. It uses meaningless connections [emphasis added] and the way the brain works to gain access to information. For example, if I mentally write the date Rome was founded with the mnemonic “BC 753 Rome came to be” as a number on an egg in the kitchen fridge, the only reason for this link between the egg in the kitchen fridge of my memory palace and the year Rome was founded is that I can remember this number.

Certainly not an attack against him, but I feel as if Sascha is making an analogistic reference to areas of mnemonics he's heard about, but hasn't actively practiced. As a result, some may come away with a misunderstanding of these practices. Even worse, they may be dissuaded from combining a more specific set of mnemonic practices with their zettelkasten practice which can provide them with even stronger memories of the ideas hiding within their zettelkasten.

There is a mistaken conflation of two different mnemonic techniques being described here. The memory palace portion associates information with well known locations which leverages our brains' ability to more easily remember places and things in them with relation to each other. There is nothing of meaningless connections here. The method works precisely because meaning is created and attributed to the association. It becomes a thing in a specific well known place to the user which provides the necessary association for our memory.

The second mnemonic technique at play is the separate, unmentioned, and misconstrued Major System (or possibly the related Person-Action-Object method) which associates the number with a visualizable object. While there is a seeming meaningless connection here, the underlying connection is all about meaning by design. The number is "translated" from something harder to remember into an object which is far easier to remember. This initial translation is more direct than one from a word in one language to another because it can be logically generated every time and thus gives a specific meaning to an otherwise more-difficult-to-remember number. As part of the practice this object is then given additional attributes (size, smell, taste, touch, etc., or ridiculous proportion or attributes like extreme violence or relationships to sex) which serve to make it even more memorable. Sascha seems break this more standard mnemonic practice by simply writing his number on the egg in the refrigerator rather than associate 753 with a more memorable object like a "golem" which might be incubating inside of my precious egg. As a result, the egg and 753 association IS meaningless to him, and I would posit will be incredibly more difficult for him to remember tomorrow much less next month. If we make the translation of 753 more visible in Sascha's process, we're more likely to see the meaning and the benefit of the mnemonic. (I can only guess that Sascha doesn't practice these techniques, so won't fault him for missing some steps, particularly given the ways in which the memory palace is viewed in the zeitgeist.)

To say that the number and the golem (here, the object which 753 was translated to—the Major System mnemonic portion) have no association is akin to saying that "zettlekasten" has no associated meaning to the words "slip box." In both translations the words/numbers are exactly the same thing. The second mnemonic is associating the golem to the egg in the refrigerator (the memory palace portion). I suspect that if you've been following along and imagining Andy Serkis gestating inside of an egg to become Golem who will go on to fight in the Roman Coliseum in your refrigerator, you're going to see Golem every time you reach for an egg in your refrigerator. Now if you've spent the ten minutes to learn the Major System to do the reverse translation, you'll think about the founding date of Rome every time you go to make an omelette. And if you haven't, then you'll just imagine the most pitiful gladiator loosing in the arena against a vicious tiger.

Naturally one can associate all their thoughts in their ZK to both the associated numbers and their home, work, or neighborhood environments so that they can mentally take their (analog or digital) zettlekasten with them anywhere they go. This is akin to what Thomas Aquinus and Raymond Llull were doing with their "knowledge management systems", though theirs may have had slightly simpler forms. Llull actually created a system which allowed him to more easily meditate on his stored memories and juxtapose them to create new ideas.

For the beginners in these areas who'd like to know more, I recommend the following as a good starting place: <br /> Kelly, Lynne. Memory Craft: Improve Your Memory Using the Most Powerful Methods from around the World. Pegasus Books, 2019.

-

-

writing.bobdoto.computer writing.bobdoto.computer

-

How a Collaborative Zettelkasten Might Work: A Modest Proposal for a New Kind of Collective Creativity by [[Bob Doto]]

Sounds a lot like the group wiki of the IndieWeb

-

-

Local file Local fileLayout 17

-

Dousa, Thomas M. “Facts and Frameworks in Paul Otlet’s and Julius Otto Kaiser’s Theories of Knowledge Organization.” Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 36, no. 2 (2010): 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/bult.2010.1720360208.

-

n stark opposition to Otlet’s insistence that an ideal KOS be impersonaland universal, Kaiser firmly held to the view that, ideally, KOSs should beconstructed to meet the needs of the particular organizations for which they arebeing created. For example, with regard to the use of card indexes in businessenterprises, he asserted that “[e]ach business, each office has its individualcharacter and individual requirements, and its individual organization. Itssystem must do justice to this individual character [11, § 76].

-

For Otlet, one of the major advantages of the UDC over alphabetical systemswas that “every alphabetical filing scheme has, through the arbitrariness of thechoice of words, a personal character, whereas the [U]DC has an impersonaland universal character” [6, p. 380].

alphabetical order vs. "semantic order" (by which I mean ordering ideas based on their proximity to each other in an area or sub-area of expertise)

-

No less important, the numerical notation served to “translateideas” into “universally understood signs,” namely numbers [13, p. 34].

Unlike Luhmann's numbers which served only as addresses, Paul Otlet's numbers were intimately linked to subject headings and became a means of using them across languages to imply similar meanings.

-

Otlet, by contrast, was strongly opposed to organizing information unitsby the alphabetical order of their index terms. In his view, such a mode oforganization “scatters the [subject] matter under rubrics that have beenclassed arbitrarily in the order of letters and not at all in the order of ideas”and so obscures the conceptual relationships between them [6, p. 380]

In this respect Otlet was closer to the philosophy of organization used by Niklas Luhmann.

-