However,evenwhenconsensuallyinstalled,usersrarelyunderstandhowspywareworksandoftenforgetaboutitspresence.[50]Cookiesarethemostpervasiveform.Theyarebitsofdatastoredondevicesandsenttobrowsersbywebsitesthatarevisitedorthroughtechniqueslike‘devicefingerprinting’,whichenableswatchingsubjectswhodeleteordonotstorecookies.[51]Theyareusednotonlyformonitoringdigitalactionsbutalsofortrackingpreferredlanguage,login,andotherpersonalsettingssuchassearchpreferencesandfortargetingadvertisingandtrackingnumbersofvisitstosites.[52]Digitaltracespickedupbycookieshavealsobeenrepurposedbysecurityagencies,suchastheNSA’sutilizationofGoogle’sadvertisingcookiestotracktargets.

- Oct 2017

-

Local file Local file

-

-

afocusontheanticipatoryandthefuturesuchthatmoreemphasisisgiventopredicting,intervening,andmanagingconsequencesratherthanunderstandingcauses;andthemoreeasyandsuccessfuladoptionandadaptionofdatatodifferentfieldswithlittlerisk

-

Thatis,ratherthanasimplequestionofchoiceorexchangeeconomy,citizensubjectsarecaughtbetweenthedemandstoparticipateandconnect—andallthereasonsandvaluestheyattachtothis—andtheinterests,imperatives,andtrade-offsconfiguredbyplatformowners.Butitwouldbewrongtoreducethistomerelytheinterestofplatformowners,whichareonlyoneelementinthemake-upofconventionssuchasbrowsing.Theconventionsofsocialnetworkinginevitablyembodythesocialandculturalnorms,rules,andcustomsofwhichcitizensubjectsareapartandtakepart

En mi caso, mi renuencia a participar de Mastodon tiene que ver con que no conozco mucha gente que esté allí y que no está conectada con la red de microblogging de la que ya participo (Twitter). Otra gente ve la misma dificultad en otras redes y tecnologías, como Telegram o el mismo Grafoscopio. En la medida en que una tecnología no le aporta valor al cotidiano, es difícil probarla, apropiarla y reapropiarla. Esto quiere decir que para aquellos a quienes nos aporta valor, es necesario construir y explicitar esos valores diferenciales para otros y alentar una comunidad dinámica (así sea pequeña) alrededor de dichas tecnologías emergentes.

-

Thesedigitaltracesareoftenreferredtoasbigdataandarepopularlydiscussedasaresource,arawmaterialwithqualitiestobeminedandcapitalized,thenewoiltobetappedtospureconomies.Throughavarietyofpracticesofvaluation,corporationsnotonlyexploitthedigitaltracesoftheircustomerstomaximizetheiroperationsbutalsosellthosetracestoothers.Forthatreason,citizensubjectswhouseplatformssuchasGooglearesometimesreferredtonotasitscustomersbutasitsproduct.

-

atrendthatshecallsa‘modernexampleofatragedyofthecommons.’[33]Justasintheclassicversion,subjectswhoprotecttheirdatacontinuetoreapthecollectivebenefits(suchasinmedicine)ofdataleftinthecommons,yetthosebenefitsarethreatenedandwilldegenerateasdatasubjectsoptout.Othersstrikeadifferentwarning,arguingthattheanonymizationofidentityleadstocrowdbehaviourandsubjectstakinglessresponsibilityforwhattheysayanddoandincreasesthelikelihoodoftheirmisbehaving.[34]Boththeargumentsforandagainstanonymizationasasolutionpresumethatwhatisatissueisprotectingthe‘datadoubles’ofcitizensubjects.

-

Numerousformsofanonymizationalsoexist,suchasthosethatinvolveexpostfactoremovalofmetadata,whichgovernmentsorbusinessesdowhensharingdatawiththirdparties.Thisisdistinctfromanonymity,whichinvolvesactionsthatavoididentificationbyusingpseudonymsorencryptionsuchasPGP(PrettyGoodPrivacy).Theseactionsperformtherighttoactwithoutbeingidentified.

-

Onlywhentrackinginvolvesdatafying(theprocessofrenderinganaction,attribute,orathingintoaquantifiedanddigitalform)canitbedigitallyanalysed.

En qué se diferencia la cuantificación de la "datificación"? Los datos pueden no ser cuantitativos. Por ejemplo "estado: triste" es una forma de dato no cuantitativo, que se podría convertir luego en cantidad a través de asociar una métrica.

-

digitaltracesalsogetcirculatedandrepurposedandinthisregardhavesociallivesbeyondthefeedbackloopsoftheirplatforms.[28]Thus,notonlyistrackingincipienttothefunctioningofspecificconventions,butthedatageneratedhasextensitysuchthatitcantravelbeyondandbetweenconventions.

-

Bynotonlyciting,repeating,anditeratingbutalsoresignifying,citizensubjectscan,andasweshallseeinchapter6indeeddo,breakconventionsandtakeresponsibility.Criticssuchasthosecitedaboveoftenslipintodeterministandstructuralistaccountsoftheworkingsofplatformsbyinferringthatusersaredeceivedandunwittinglysubmittotheresultsofsearchqueries,newsfeeds,ortrendsandthattheseareforces‘shaping’themandsocieties.

Es decir que la pregunta de investigación de la tesis está en diálogo con la formas de ser ciudadano en la medida en que no se asume un determinismo tecnológico, sino se presume, de entrada, que podemos cambiar las tecnologías que nos cambian y por tanto somos agentes de dicho cambio.

-

TarletonGillespiearguesthattensionsbetweenusersandthedesignersoftheTwitteralgorithmarepartoflargerstakesinthe‘politicsofrepresentation.’Itisatensionunderscoredbyaconflictbetweenpeople’swilltoknowandbevisibletoothersandTwitter’simperativetodrawnewusersintonewconversations.Butsignificantly,Gillespienotesthatsuchalgorithmsnotonlyarebasedonassumptionsabouttheimageofapublictheyseektorepresentbutalsohelpconstructpublicsinthatimage.Thesamecouldbesaidofotherplatforms

En el caso de los Data Selfies, lo que queremos hacer es presentar otra idea sobre nosotros mismos, nuestros gobernantes e instituciones públicas (principalmente). Particularmente por la sensación de no ser representados apropiadamente por la línea de tiempo de Twitter.

-

Inthisinstance,criticsprotestedthatTwitterwasinvolvedincensoringpoliticalcontent,butothershaveshownthatthecomplexalgorithmsoftheplatformorganizeandfiltercontentinwaysoftenbeyondtheintentionsoftheirdesigners.Ratherthanasimplemeasureofpopularity,thealgorithmisbasedonacombinationoffactors,andthosethatTwitterhasrevealedincludeidentifyingtopicsthatareenjoyingasurgeinaparticularway,suchaswhethertheuseofatermisspiking(acceleratingrapidlyratherthangradually),whetherusersofatermformatightsingleclusterorcutacrossmultipleclusters,whethertweetsareuniqueormostlyretweetsofthesamepost,andwhetherthetermhaspreviouslytrended

Se podría invitar a una figura (política por ej) de relativo renombre a que maneje su presencia en línea desde un lugar como los de Indie Web (Mastodon, Known, etc) y mirar qué ocurre con sus redes de seguidores. ¿Alguno migra a una nueva red para tener interacciones ampliadas con dichas figuras?

-

filterbubblessortandnarrowtheknowledgecitizensubjectsaccessandseparatethemintoindividualizeduniverseswheretherulesoftheirformationareinvisible.

Deconstruir la burbuja: Scrappear los resultados mostrados por el navegador y mirar dónde ellos nos conectan o aislan de otras personas que han buscado lo mismo. Para ello se podría usar el plugin que conecta a Pharo con Chrome.

-

SomescholarshavechallengedthesortingeffectsoftheGooglesearchenginetohighlightthatitsoperation(1)isbasedondecisionsinscribedintoalgorithmsthatfavouranddiscriminatecontent,(2)issubjecttopersonalization,localization,andselection,and(3)threatensprivacy

-

platformssuchasGoogleandFacebookthatoperatelike‘predictionengines’by‘constantlycreatingandrefiningatheoryofwhoyouareandwhatyou’lldoandwantnext’basedonwhatyouhavedoneandwantedbefore

-

Whileblockingisoftengivenmoreattention,ofgreaterconcernishowsortingorganizesaccesstoknowledgeinmoreperniciousways.‘Googling’hasbecomearegularizedactionforfindingknowledgeinwaysthatareoftentakenforgrantedornotproblematizedbutsopervasiveanddominantthatthesearchenginehasgivenrisetotheterm‘googlization.’ThetermiscoinedtosuggestthatGoogleaffectseverything

-

Cohenreferstoblockingas‘architecturesofcontrol’and‘regimesofauthorization’thatareauthoritarianinthegenericsensethattheyfavourcompliantobediencetoauthority.[11]Ratherthanexperiencingrules—whichneednotbeexplainedordisclosed—shearguesthatusersexperiencetheireffects,whichconsistofpossibilitiesforactionthatnetworkscreate.Sowhileconcernsaboutthesurveillanceandcollectionofdigitaltracesaremostcontroversial(discussedbelow),thetransparencyofnetworkprocessesandhowaccesstoknowledgeisbeingfilteredarelessvisibleandcontrollable.Filteringalsooccursthroughtheauthorizationsattachedtocontentanddevices

[...] So while sharing is a calling, it is increasingly only within certain regimes of authorization that sharing operates, and in this regard it can be understood as a form of submission.

-

Tanto Leo como Grafoscopio tienen limitaciones (y propósitos distintos). Sin embargo, en el caso de Grafoscopio, siento que puedo englobar y superar dichas limitaciones más fácilmente, no tanto porque lo hice desde el comienzo, sino por el entorno de live coding que me permite explorar y modificar el entorno en caliente.

-

Questionsremain.Whywasthereafilterinthefirstplace?Whowasbeingprotected?Byhavingunblockedtheresultofourquery,shouldwehavefeltreliefthatouractivitywasnotcriminal?HowwouldwehavereactedhadtheBritishLibrarycontinuedtoblockaccesstoBanksy’swebsite?

¿Cuáles son las fronteras del ciberespacio invisibles para nosotros? Hay burbujas que se aplican sin que lo sepamos, independientemente de si usamos o no un motor de búsqueda que construya dichas limitaciones, como Google, que lo hace ampliamente o DuckDuckGo, que lo restringe a la ubicación geográfica?. ¿Puede ese filtro se deconstruido desde lo que nos muestra el cliente web?

-

decisionsonretaining,filtering,monitoring,andsharinginformationaredispersedandhavepoliticaleffectsforcitizensacrossjurisdictions.Ratherthanbeinghierarchicallyorganized,discretesystems,technologiesandpracticesaredecentredanddispersedacrossnumerouscentresofcalculation.

-

AseriesofglobalstudiesbytheOpenNetInitiative(ONI)hasdocumentedhowstates—especiallyintheGlobalNorth—arecreatingbordersincyberspacebybuildingfirewallsatkey‘Internetchokepoints,

-

Threeactsexpressmoststronglytheplayofobedience,submission,andsubversionthatcitizensubjectsengageintheconstitutionofclosings:filtering,wherecitizensubjectssubmittoregulateandprotectthemselvesoragreetobeprotectedbyauthorities,trackingwherecitizensubjectsenterintogamesofevasion,andnormalizingwherethewaysofbeingcitizensubjectsincyberspaceareiterativelymodulatedtowardsdesiredendsbyprivateandpublicauthorities.

-

EvgenyMorozov,forexample,arguesthatopennessisconfiguredbypoliticalchoicesandinrelationtospecific‘digitaltechnologies’andthatthosechoicesshouldbebothresistedandpoliticallydebated.Butlikethemisfiresofcriticswenotedattheendofchapter4,controlisgivenovertohowdigitaltechnologiesareconfiguredwithoutaccountingforhowpeopleactthroughtheInternet,theconventionstheyrepeat,iterate,cite,orresignify,andtheperformativeforceoftheirengagements

-

Soifopennessisanimaginarythatcallsuponcitizensubjectstoparticipate,thenclosingsseektofurtherconfiguretheactionsthroughwhichparticipationisdone.Butthisisneversettled.Thetworemainintension.

En la medida en que leo y tengo que combinar distintas tecnologías para hacerlo (Docear, Linux, Hypothesis), principalmente porque ellas no se integran bien entre sí, pienso en cómo Grafoscopio soportaría estas formas de lectura integrada. Quizás asumiendo el papel de Docear, implementando funcionalidades de mapas mentales, extendíendose hacia los mapas argumentativos y comunicándose con Hypothesis para leer la tabla de contenido, hacer lecturas anotadas y visualizaciones de datos de lo leído.

Avanzar en esta línea me distraería de la escritura de la tesis misma, por lo que estas características serían implementadas y exploradas de manera orgánica, desde las que más fácilmente se integran al cotidiano (ejp: visualizar datos de lecturas), hacia las más demandantes/esotéricas (reemplazar Docear).

La pregunta por cómo cambiamos los artefactos digitales que nos cambian ha permeado el cotidiano no sólo desde sus posibilidades teóricas, sino desde sus implementaciones prácticas, ahora que cuento con un artefacto prototipo para dichos cambios.

-

Thatthesedemandshaveemergedinthespanofonlyafewyearsatteststowhatwecallthe‘closings’ofcyberspace.ThesedemandsandtheirclosingsareeffectsofthewayinwhichactingthroughtheInternethasresignifiedquestionsofvelocity,extensity,anonymity,andtraceability.Velocitycallsforregularandongoingvigilanceaboutrapidlychangingtechnologies,protocols,practices,platforms,andrulesaboutbeingdigital;extensitycallsforawarenessofwhereandtowhomdigitalactionsreach;anonymitycallsforlimitingandprotectingexposureandbeingcautiousaboutthepresumedidentitiesofothers;andtraceabilitycallsformanaginghowactionsaretracked,analysed,manipulated,andsortedbyunknownothersandforunknowablepurposes.Allofthesedemandsspringnotfromparticipating,connecting,andsharingalonebuttherelationsbetweenandamongbodiesactingthroughtheInternet,whichismadeupofconventionsconfiguredbytheactionsofdispersedanddistributedauthorities.Itistotheseconfiguringactions,whichwecalltheclosingsofcyberspace,thatweturntointhenextchapter,withafocusonfiltering,tracking,andnormalizing.

-

subjectsofpowerincyberspacehavecomeintobeingthroughtheaccumulationofrepetitiveactions,throughtheirtakingupandembeddingofconventionsintheireverydaylivesinhomes,workplaces,andpublicspaces.Itisthroughtheactsofparticipating,connecting,andsharingthatthesehavebecomedemandsandlearnedrepertoiresthatarenotseparatefrombutindeliblyshapedbyandshapingofsubjects.

Hackers are ordinary

-

JonathanFranzenaccusesAmazonofturningliterarycultureintoshallowformsofsocialengagementconsistingof‘yakkersandtweetersandbraggers’andTwitterasthe‘ultimateirresponsiblemedium.’[89]Thesemisfiresproduceatleasttwoinfelicities.First,inadvertentlytheyendupascribingmorepowertosuchcorporationsasAmazonorGooglethantheyactuallyhave.WhilemuchattentionisgiventotheautomatedandcomputationalaspectsofGoogle,theworkingsofthesearchengineareunstableandrelyonthedistributed,heterogeneous,anddynamicactionsofnotonlyalgorithmsbutalsoengineers,operators,webmasters,andusers.[90]Second,theyascribelesspowertopeoplethantheyactuallyhave.WhiletherulesofGoogle’salgorithmandfunctionssuchasautocompleteareatightlyheldsecret,Google’soperationisshapedandmediatedbythesearch-and-findbehavioursofcitizensubjects

-

Cyberspaceisthuslikeotherspacesthatdemandsecuringoneselfthroughmaterialsandtechnologiesbutalsothroughhabits,norms,andprotocols

All of these make further demands on subjects to acquire considerable forms of capital, from technical expertise to financial resources and time. Even though citizen subjects are interpellated to respond to these calls, the solutions are increasingly individualized, personalized, and privatized.

-

Opennessinrelationtosharingthushasmultiplemeaningsandisamatterofpoliticalcontestationthatbeliesthepositiveformulationsofitasafoundingimaginaryofcyberspace.Ontheonehand,itmeansmakinggovernmentstransparent,democratizingknowledge,collaboratingandco-producing,andimprovingwell-beingbutontheother,exposing,makingvisible,andopeningupsubjectstovariousknownandunknownpracticesandinterventions.[76]Alongwithparticipatingandconnecting,sharinggeneratesthesetensions,especiallyinrelationtowhatisoftenreducedtoasquestionsofprivacy.Thistensionthatopennessgeneratesincreasinglycreatesadditionaldemandsthatcitizenssecurethemselvesfromandberesponsibleforthepotentialandevenunknowableconsequencesoftheirdigitalconduct.

-

Popularlyknownasthe‘quantifiedself’,datatracesproduceacompulsiontonotonlyself-trackbutsharethisdatasothatsubjectscanmonitorthemselvesinrelationtoothersbutalsocontributetoresearchon,forexample,healthconditions.Ironically,whilegovernmentprogrammesforsharinghealthdatahavebeenscuppered,thesharingofhealthinformationthroughprivateorganizationssuchas23andMe(DNAprofilingofmorethan700,000members)andPatientsLikeMe(healthconditionsofmorethan250,000members)areproliferatingandpromotingdatasharingforthepublicgoodofadvancingmedicine.[62]Governmentsandcorporationsalikecalluponcitizensubjectstosharedataaboutthemselvesasanactofcommongood.Throughdisciplinarymethodstheycompelcitizensubjectstoconstitutethemselvesasdatasubjectsratherthanmakingrightsclaimsabouttheownershipofdatathattheyproduce.

Hay simplemente datos que no registramos y tenemos la tendencia dejar una sobra digital pequeña en lugar de una grande. Los data selfies son maneras de reapropiar las narrativas sobre los datos y pensarnos de otras maneras desde ellos, en lugar de dejar esas lecturas sólo a quienes nos mercantilizan.

-

Butherethesharingofgovernmentdataisalsodirectedatcommercialbodiestowardsstimulatingamarketofapplications,platforms,andanalyticsaswellastoinnovateservices,contributetoaworldwidegovernmentdatamarket,andstimulategreaterprivate-sectorprovisionofpublicservices

-

Sharingexpertiseisalsotheethosofhackingevents,whicharenotonlyforumsorganizedbyandforactivistsbutnowcommonlybygovernmentsandcorporations.Thesamecanbesaidofactionsthatinvolvecollectiveproblemsolvingasmodesofsharingone’slabour,skills,anddatathroughinitiativessuchasthecitizenscienceprojectsofZooniverseor,incontrast,Amazon’sMechanicalTurk.[55]However,likeotherone-to-manysharingplatforms,thesearealsoorganizedondifferentprinciples.GalaxyZooandsimilarformsofcitizenscienceinvolvedonationsofvoluntarylabourforusuallybroaderpublicgoodsandobjectives.

La pregunta es también ¿quién coloca la pregunta/problema? tanto en las hackatones, como el las actividades de ciencia abierta.

-

Actsofconnectingrespondtoacallingthatpersistseveninlightofthetraceabilityofdigitalactionsandconcernsaboutprivacy.Thosewhoaremakingrightsclaimstoprivacyanddataownershiparebyfaroutnumberedbythosewhocontinuetosharedatawithoutconcern.Thatadatatraceisamaterialthatcanbemined,shared,analysed,andacteduponbynumerouspeoplemakestheimaginaryofopennessvulnerabletooftenunknownorunforeseeableacts.Butdigitaltracesalsointroduceanothertension.Anothercalling,thatofsharingdigitalcontentandtraces,isademandthatevokestheimaginaryofopennessfundamentaltotheveryarchitectureofsharedresourcesandgifteconomythatformedtheonce-dominantlogicofcyberspace

-

VanDijckconcludesthatdespitetheseandotherconstraintsonagencyandparticipating,optingoutofsocialmediaisdifficult,especiallyifbeingdigitallyliterateandmaintainingacriticalstanceinrelationtocontemporarycultureareofvalue.[51]Franklinechoesthisinherstancethatsuchpropositionssee‘unplugging’as‘simplyatechnical

matter when evidence shows that there is a little understood psychoemotional component to being and staying in touch via the internet.’

-

Toputitbluntly,fromourperspective,popularcriticshavebecometooconcernedaboutcyberspacecreatingobedientsubjectstopowerratherthanunderstandingthatcyberspaceiscreatingsubmissivesubjectsofpowerwhoarepotentiallycapableofsubversion.

-

Or,aswewouldputit,actingthroughtheInternetandmakingconnectionswithothersdoesnotreplace,displace,orsupplantotherwaysofactinginsocialorculturalspacesinwhichweareembedded.

-

thechangethatsocialmediahasintroducedfromcommunity-oriented‘connectedness’toplatform-andowner-configured‘connectivity.’[41]WiththeintroductionofWeb2.0,shearguesthatconnectivitycaptureshowsocialityhasbecometechnologicallymediatedthroughcommercialplatformsthatorganizeandmanageinteraction.

En el Data Week experimentamos un regreso hacia las plataformas comunitarias, pues si bien la convocatoria se realiza por Twitter o Meetup, los asistentes terminan teniendo presencia en dichas plataformas alternativas.

-

Inrelationtoteens,danahboydarguesthatsocialmediaenablesthemnotonlytoparticipatebuttohelpcreate‘networkedpublics’,whichare‘constructs’throughwhichteensconnectandimaginethemselvesaspartofacommunitythatisnotindependentfrombutverymuchconnectedtotheirrelationsin‘real’space.

-

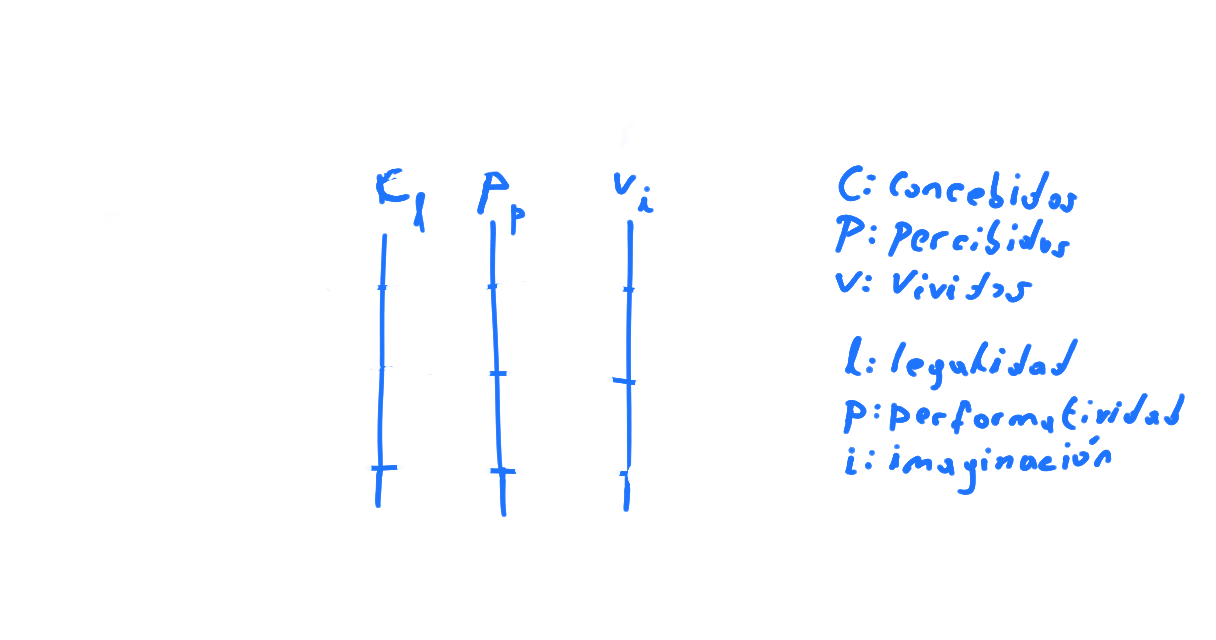

Howcanthecallingtoparticipatethatwehaveidentifiedproducedigitalcitizenswhoseactsexceedtheirintentions?Toputitdifferently,atensionexistsbetweenthewaysinwhichthefigureofthedigitalcitizenisconceivedinhegemonicimaginariesandlegaldiscoursesandhowsheisperformativelycomingintobeingthroughactionsthatequiphertobeacitizeninwaysthatarenotacknowledgedoralwaysintended.

-

Forexample,whatresourcesofcyberspacedodigitallyequippedsubjectshavetheauthorizationtoaccessasaresultoftheworkingsofsearchalgorithmsandfiltersortheprotocolsthatgovernandnormalizetheretention,storage,sharing,anddiscoverabilityofinformation?[36]Iflegalityandimaginaryconfigurethecitizenasasubjectofpowerandplacedemandsonhertoparticipatedigitally(submission),whatwefindinterestinghereandinrelationtohowwehaveunderstoodbeingdigitalcitizensistheperformativityofparticipatingthatprovidesaglimpseofthecitizenasalsoapotentialsubjectofsubversion.How,forexample,doesparticipatinggiverisetosubversiveactions,suchasthoseofcriticalcitizenscience?[37]Or,asMatthewFullerandAndrewGoffeyputit,howdoinjunctionssuchasGoogle’s‘Don’tbeevil’maximbeliethepropensitiesthatareactivatedbyrelativelyunstablesociotechnicalarrangementsthataregenerativeof‘unintendedorsecondaryeffects’?

¿Cómo las infraestructuras legales y tecnológicas soportan la bifurcación y recombinación? ¿Cómo esto empodera otras prácticas ciudadanas?

-

the‘actofhangingoutonline[wasfoundtohave]enormouspotentialforcreatingthecivicnetworksthatsupportreal-worldpoliticalengagement.’

Esto lo experimente por mi cuenta con la Ley Lleras y otras formas de activismo.

-

Nevertheless,manystudieshavefoundlittleevidencethatsociallyandeconomicallydisadvantagedgroupparticipationincreaseswhenpoliticsisconductedthroughtheInternet,whetherinwaysthatmimicofflineforms,suchaspetitions,ornewones,suchassocialmedia

Hay un "remedo" de participación, que presupone que porque tenemos acceso a Internet estamos participando. La participación real debe estar asociada a modelos socioeconómicos que la hagan posible y la valoren más allá del extractivismo y la exclusión actual.

-

Despitetheirdifferences,theydogenerallyshareanimaginaryofcitizensubjectsasalreadyformedassubjectsofsubmission,wheretheirparticipationisamatterofaccess,skills,andusage.Itisanimaginaryofacitizenasasubjectwhoisoftensubmissive(ifnotobedient)andisactiveonlyinwaysrecognizedbygovernmentpoliciesandprogrammes.Alleffortsareaimedatdiscipliningsubjectsalongdigitalinclusionscalesthroughactionsthatinvolveaccess,skills,motivation,andtrust.Itisthroughrepetitionthattheseactionsbecomeembodiedandthroughwhichcitizensubjectsbecomegovernable.Digitalinclusionthusplacesdemandsonthecitizensubjecttouptaketheseactions,tobeskilledandtooled,andtolearnandbecomeknowledgeableandcompetentinlookingafterherselfandgoverninghersocialneeds

[...] But to do so also demands vigilance in maintaining and re-equipping oneself in terms of both skills and infrastructures in the face of constant change: ‘System outages, constant software updates, platform redesigns, network upgrades, hardware modifications, and connectivity changes make netizenship in the bitstream a rather challenging way of life.

Muchos de los llamados que hace el Gobierno presuponen un tipo de ciudadano que participa de manera predefinidas por el mismo Gobierno, usualmente complacientes e inactivas o asociadas exclusivamente a modos neoliberales/capitalistas de participación vía el "emprendimiento".

-

‘equipthewholecountrywiththeskills,motivation,andtrusttogoonline,bedigitallycapableandtomakethemostoftheinternet....Ifwesucceed,by2020everyonewhocanbedigitallycapable,willbe.’

Grafoscopio 2020 puede ser un llamado a pensar ese futuro optimista y empoderante y los compromisos con el mismo desde el mediano plazo.

-

Mossbergeretal.,forexample,understanddigitalcitizenshipastheabilitytofullyparticipateinsocietyonline,whichrequiresregularaccesstotheInternet,withadequatedevicesandspeeds,technologicalskillsandcompetence,andinformationliteracy.[21]Equippingthusincludesnotonlyhardware,suchasinstallingcomputersinclassroomsandlibrariesandexpandinghigh-speedbroadbandservices,butalsodevelopingskillsandcapabilitiesthroughtrainingcoursesincomputing,coding,andprogramming

Una de las cosas que hemos hecho es apropiarnos de los ciclos de actualización tecnológica para ponerlos en nuestras manos sin andar corriendo detrás de la última actualización.

-

Theempoweringpossibilitiesofaccessingandworkingwithdataalsounderpin‘opengovernmentdata’programmes.Opennessisextendedtomakinggovernmenttransparentthroughapublicrighttodataandfreedomtoinformation,aversionthatisalsoadvancedbycivicorganizationssuchasmySociety.[19]Thesecallforthanimaginaryofcitizensasdataanalystsequippedwiththeskillsnecessarytoanalysetheircommercialtransactionsandthusmakebetterdecisionsortoanalysethetransactionsofgovernmentsandthusholdthemtoaccount.

Agregar la gráfica de la manera en la cual se puede hacer al gobierno:

-

Becomingadigitalcitizeninvolvesrespondingtocallingswhereparticipatingisoneofthem.Participatingdemandsspecificactionsofskillingandtoolingthatcitizensneedtoundertaketoequipthemselves.

Escoger un conjunto de competencias sobre las cuáles ejercer la ciudadanía.

-

ForHalfordandSavage,whetherliberatingordividing,cyberspace(orwhattheyrefertoasthe‘Web’)isalwaysconsideredasanalreadygivenspace,anditssubjectsareseparate,independent,andpreformedratherthanperformed.Ratherthanassumingthat‘pre-formedsocialgroups“use”(ordon’tuse)technologies’,theyidentifya‘morecomplexprocessofmutualinteractionandstabilisation’wheredigitaltechnologiesarenotseparatedfromsocialprocessesbutinsteadinvolvedinconstitutingsubjectsindiverseandpervasiveways.[16]Inotherwords,theyadvancethattheWebisnotindependentfromtheactionsofsubjects.

[...] What they identify as complex social processes between digital technologies and the formation of subjects, we specify as the digital acts through which citizen subjects are called upon by legality, performativity, and imaginary.

-

‘A“digitaldivide”isneveronlydigital;itsconsequencesplayoutwhereverpoliticalandeconomicdecisionsaremadeandwherevertheirresultsarefelt.’

-

Inequalityisexpressedasleadingtotwodivisions:betweenthosewhodoanddonothaveaccessandbetweenthosewhodoordonotcontributetocontentorleavedigitaltraces.

Aumentar la capacidad en la comunidad de base para enunciar sus propias voces.

-

Wefocusonthreeactsthatsymbolizeparticularlywellthedemandsforopenness—participating,connecting,andsharing.Theseactsarenotallinclusive;therearecertainlyotheracts,buttheycoverwhatwesuggestarekeydigitalactsandtheirenablingdigitalactions

-

Ifwefocusoncallingsandtheactionstheymobilizeandhowtheymakeactspossible,wealsoshiftourfocusfromafreedomversuscontroldichotomytotheplayofobedience,submission,andsubversion.Thisisaplayconfiguredbytheforcesoflegality,performativity,andimaginarywhichcalluponsubjectstobeopenandresponsibleandthroughwhichmostlygovernmentalbutalsocommercialandnongovernmentalauthoritiestrytomaintaintheirgripontheconductofthosewhoaretheirsubjects.

-

Itisoftenforgottenthatthecitizensubjectisnotmerelyanintentionalagentofconductbutalsoaproductofcallingsthatmobilizethatconduct

-

WeagreewithCohenontheseeminglyparadoxicalrelationbetweenimaginariesofopenness(copyleft,commons)andclosedness(copyright,privacy)andtheirconnectiontoinformationfreedomandcontrol.Sheisrighttoarguethatthisparadoxcannotberesolvedinlegaltheoryfortwomainreasons.First,freedomandcontrolarenotseparatebutrequireeachother,andhowthisplaysoutinvolvescalibrationwithinspecificsituatedpractices.[6]Second,andrelatedly,legaltheorydependsonaconceptionofabstractliberalautonomousselvesratherthansubjectsthatemergefromthecreative,embodied,andmaterialpracticesofsituatedandnetworkedindividuals

-

Today,beingopenhasbecomeademandonorganizationsandindividualstoshareeverythingfromsoftwareandpublicationstodataaboutthemselves.Fromopendata,opengovernment,opensociety

-

Wecannotsimplyassumethatbeingadigitalcitizenalreadymeanssomething,suchastheabilitytoparticipate,andthenlookforwhoseconductconformstothismeaning.Rather,digitalactsarerefashioning,inventing,andmakingupcitizensubjectsthroughtheplayofobedience,submission,andsubversion

Nosotros hablábamos de deliberación, implementación y seguimiendo sobre las decisiones, como forma de participación. Desde el Data Week estamos yendo del seguimiento a las primeras.

-

Beingdigitalcitizensisnotsimplytheabilitytoparticipate.[2]Wediscussedinchapter1howJonKatzdescribedanethosofsharing,exchange,knowledge,andopennessinthe1990s.Today,thesehavebecomecallingstoperformourselvesincyberspacethroughactionssuchaspetitioning,posting,andblogging.Theseactionsrepeatedlycalluponcitizensubjectsofcyberspace,andherewewanttoaddresstheirlegal,performative,andimaginaryforce.

-

Tounderstanddigitalactswehavetounderstandspeechactsorspeechthatacts.Thespeechthatactsmeansnotonlythatinorbysayingsomethingwearedoingsomethingbutalsothatinorbydoingsomethingwearesayingsomething.ItisinthissensethatwehaveargueddigitalactsaredifferentfromspeechactsonlyinsofarastheconventionstheyrepeatanditerateandconventionsthattheyresignifyareconventionsthataremadepossiblethroughtheInternet.Ultimately,digitalactsresignifyquestionsofanonymity,extensity,traceability,andvelocityinpoliticalways.

-

Toputitsimply,whiledigitalactstraverseborders,digitalrightsdonot.Thisiswherewebelievethinkingaboutdigitalactsintermsoftheirlegality,performativity,andimaginaryiscrucialsincethereareinternationalandtransnationalspacesinwhichdigitalrightsarebeingclaimedthatifnotyetlegallyinforceareneverthelessemergingperformativelyandimaginatively.Yet,arguably,someemergingtransnationalandinternationallawsgoverningcyberspaceinturnarehavinganeffectonnationallegislations.Toputitdifferently,theclassicalargumentabouttherelationshipbetweenhumanrightsandcitizenshiprights,thattheformerarenormsandonlythelattercarrytheforceoflaw,isnotahelpfulstartingpoint.

-

Theimportantthingistoseparateacts(locutionary,illocutionary

The important thing is to separate acts (locutionary, illocutionary, perlocutionary), forces (legal, performative, imaginary), conventions, actions, bodies, and spaces that their relations produce.

-

Itiswellnighimpossibletomakedigitalutteranceswithoutatrace;onthecontrary,oftentheforceofadigitalspeechactdrawsitsstrengthfromthetracesthatitleaves.Aswesaidinchapter2,eachofthesequestionsraisedbydigitalactscanarguablybefoundinothertechnologiesofspeechacts—thetelegraph,megaphone,radio,andtelephonecometomindimmediately.Butitiswhentakentogetherthatwethinkdigitalactsresignifythesequestionsandcombinetomakethemdistinctfromspeechacts,intermsofboththeconventionsbywhichtheybecomepossibleandtheeffectsthattheyproduce.

-

Digitalactswillnoteliminatedistance(weunderstanddistancehereasnotmerelyquantitativebutalsoaqualitativemetric),butthespeedwithwhichdigitalactscanreverberateisphenomenal.

Estos efectos de reverberación fueron sentidos en la Gobernatón y, en la medida en que se crea capacidad en la base y no sólo se reacciona, también se sienten en los Data Weeks, con menos potencia.

-

‘codeistheonlylanguagethatisexecutable.’[49]‘So[forGalloway]codeisthefirstlanguagethatactuallydoeswhatitsays—itisamachineforconvertingmeaningintoaction.’[50]WithAustin(andWittgenstein),thisconclusioncomesasamajorsurprisetous.Aswehavearguedinthischapter,forAustin(andWittgenstein)languageisanactivity,andinorbysayingsomethinginlanguagewedosomethingwithit—weact.Toputitdifferently,languageisexecutable.[51]Thereisnouniquenesstocodeinthatregard,althoughwhilecodeislikelanguage,itisdifferent.WethinkthatdifferenceistobesoughtinitseffectsandtheconventionsitcreatesthroughtheInternetratherthaninitsostensibleuniquenature

El lenguaje es ejecutable!

-

ForGalloway,‘now,protocolsreferspecificallytostandardsgoverningtheimplementationofspecifictechnologies.Liketheirdiplomaticpredecessors,computerprotocolsestablishtheessentialpointsnecessarytoenactanagreed-uponstandardofaction.’

-

ThepremiseofthisbookisthatthecitizensubjectactingthroughtheInternetisthedigitalcitizenandthatthisisanewsubjectofpoliticswhoalsoactsthroughnewconventionsthatnotonlyinvolvedoingthingswithwordsbutdoingwordswiththings.

-

Ifcallingssummoncitizensubjects,theyalsoprovokeopeningsandclosingsformakingrightsclaims.Weconsideropeningsasthosepossibilitiesthatcreatenewwaysofsayinganddoingrights.Openingsarethosepossibilitiesthatenabletheperformanceofpreviouslyunimaginedorunarticulatedexperiencesofwaysofbeingcitizensubjects,aresignificationofbeingspeakingandactingbeings.Openingsarepossibilitiesthroughwhichcitizensubjectscomeintobeing.Closings,bycontrast,contractandreducepossibilitiesofbecomingcitizensubjects

-

Whatwemeanbythisisthatasaclaim,theutterance‘havearightto’placesdemandsontheothertoactinaparticularway.

[...] This is the sense in which the rights of a subject are obligations on others and the rights of others function as obligations on us.

-

Thisindividualisautonomousnotbecauseitisseparateorindependentfromsocietybutasitsproductretainsthecapabilitytoquestionitsowninstitution.Castoriadissaysthatthisnewtypeofbeingiscapableofcallingintoquestiontheverylawsofitsexistenceandhascreatedthepossibilityofbothdeliberationandpoliticalaction.

Esta parte se conecta con Fuchs y la dualidad agencia estructura

-

Theseareimaginariesnotbecausetheyfailtocorrespondtoconcreteandspecificexperiencesorthingsbutbecausetheyrequireactsofimagination.Theyaresocialbecausetheyareinstitutedandmaintainedbyimpersonalandanonymouscollectives.Beingbothsocialandimaginary,theseinstitutesocietyascoherentandunifiedyetalwaysincoherentandfragmented.Howeachsocietydealswiththistensionconstitutesitspolitics

Grafoscopio y el Data Week se ubican en imaginarios sociales sobre lo que es la participación política.

-

Tounderstandcitizensubjectswhomakerightsclaimsbysayinganddoing‘I,we,theyhavearightto’,wearemovingfromthefirstpersontothesecondandthethird,fromtheindividualtothecollective.Weneedtoconsidertwoadditionalforcesthatmakeactspossible.Thetwoforcesaretheforceofthelawandtheforceoftheimaginary.

Grafoscopio también permite esos pasos de lo individual a lo colectivo, desde la imaginación y lo legal.

-

Onthecontrary,citizensubjectsperformativelycomeintobeinginorbytheactofsayinganddoingsomething—whetherthroughwords,images,orotherthings—andthroughperformingthecontradictionsinherentinbecomingcitizens.

-

ThisistheprincipalreasonwhyweneedtoinvestigatenotonlythingsdoneinorbyspeakingthroughtheInternetbutalsothingssaidinorbydoingthingsthroughtheInternet.

-

‘Theforceoftheperformativeisthusnotinheritedfrompriorusage,butissuesforthpreciselyfromitsbreakwithanyandallpriorusage.Thatbreak,thatforceofrupture,istheforceoftheperformative,beyondallquestionoftruthormeaning.’[22]Forpoliticalsubjectivity,‘performativitycanworkinpreciselysuchcounter-hegemonicways.Thatmomentinwhichaspeechactwithoutpriorauthorizationneverthelessassumesauthorizationinthecourseofitsperformancemayanticipateandinstatealteredcontextsforitsfuturereception.’[23]Toconceiveruptureasasystemicortotalupheavalwouldbefutile.Rather,ruptureisamomentwherethefuturebreaksthroughintothepresent.[24]Itisthatmomentwhereitbecomespossibletodosomethingdifferentinorbysayingsomethingdifferent.

Acá los actos futuros guían la acción presente y le dan permiso de ocurrir. Del mismo modo como el derecho a ser olvidado es un derecho futuro imaginado que irrumpe en la legislación presente, pensar un retrato de datos o campañas políticas donde éstos sean importantes, le da forma al activismo presente.

La idea clave acá es hacer algo diferente, que ha sido el principio tras Grafoscopio y el Data Week, desde sus apuestas particulares de futuro, que en buena medida es discontinuo con las prácticas del presente, tanto ciudadanas, cono de alfabetismos y usos populares de la tecnología.

-

Thekeyissueinspeechactsbecomeswhether,andifsotowhatextent,whatissayableanddoablefollowsorexceedssocialconventionsthatgovernasituation.

-

Byadvancingtheideathatspeechisnotonlyadescription(constative)butalsoanact(performative),Austinushersinaradicallydifferentwayofthinkingaboutnotonlyspeakingandwritingbutalsodoingthingsinorbyspeakingandwriting.

-

butbodiesandtheirmovementsareimplicitinspeechthatacts.

-

Toputitdifferently,Austin’sconcernwithinfelicitousisnotaregretonhispartbutarecognitionthatspeechdoesnotonlyact,italsocanfailtoactorfailtoactinwaysanticipated.

-

Bysayingsomething,Ihaveaccomplishedsomething.Thus,‘of’sayingsomethinghasmeaning(locutionaryacts),whereas‘in’or‘by’sayingsomethinghasforce(illocutionaryandperlocutionaryacts).

-

Moreover,ourconcernwiththeInternetisnotthespeakingsubjectassuchbuthowmakingrightsclaimsbringscitizensubjectsintobeing.Howdodigitalactsbringcitizensubjectsintobeing?DoestheInternetintroducearadicaldifferenceforunderstandingcitizensubjects?DoesthelanguageoftheInternet—code—worklikenaturallanguage?

-

Thistraversingofactsproducesconsiderablecomplexitiesinbecomingdigitalcitizens.Second,weneedtospecifytowhatextentcertainrightsclaimedbydigitalactsareclassicalrights(e.g.,freedomofspeech),towhatextenttheyareanalogoustoclassicalrights(e.g.,anonymity),andtowhatextenttheyarenew(e.g.,therighttobeforgotten).

Tags

- trabajo

- privacy

- anonimato

- ciberespacio

- enactive citizenship

- normalización

- sorting

- infraestructuras de bolsillo

- apertura vs clausura

- dataveillance

- filter bubbles

- cosificación

- compromiso

- apertura

- open government

- corporeidad

- emprendimiento

- diario de campo

- tesis

- infraestructuras comunitarias

- capacidad

- sumisión

- modificación recíproca

- gentrificación

- brecha digital

- protocolos

- redes sociales

- comunidades virtuales

- grafoscopio

- blocking

- callings

- rastreo

- reapropiación

- recursive publics

- bifurcación

- prototipo

- fronteras

- diálogo de materialidades

- digital acts

- subversión

- filtrado

- control vs libertad

- predicción

- autonomía

- estructura

- cuantificar

- extensibilidad

- hackathon

- desigualdad

- networked publics

- data doubles

- spyware

- extractivismo

- convención

- ensamblajes

- political participation

- autoexpresión

- velocidad

- cookies

- Ley Lleras

- data profiling

- speech acts

- bienes comunes

- gobernatón

- activism

- datafying

- matoneo

- big data

- data selfies

- resistencia

- live coding

- data week

- participación

- politics

- digital rights

- infraestructura

- espacios

- marginalidad

- distancia

- Grafoscopio 2020

- data activism

- kanban: por hacer

- forces of subjectivation

- agencia

- representation

- dicotomías

- tesis: resultados

- artesanía

- self empowerment

- imaginarios sociales

- digital shadow

- transparencia

- tesis: marco teórico

- tesis: gráficas

- performance

- soberanía de datos

- digital citizenship

- idea clave

- trazabilidad

- control

- critical analysis

Annotators

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

"If you go to Europe, politicians don't matter. The people making the decisions in Europe are bankers," he said. "The technicians of finance are making the decisions there. It has very little to do with democracy or the will of the people. And we are hostage to that because we like our iPhones."

-

The acclaimed and bestselling novelist, who denies himself access to the internet when writing, was talking at the Hay festival in Cartagena, Colombia. "Maybe nobody will care about printed books 50 years from now, but I do. When I read a book, I'm handling a specific object in a specific time and place. The fact that when I take the book off the shelf it still says the same thing – that's reassuring," said Franzen

-

- Sep 2017

-

Local file Local file

-

wewillspecifydigitalacts—callings(demands,pressures,provocations),closings(tensions,conflicts,disputes),andopenings(opportunities,possibilities,beginnings)—aswaysofconductingourselvesthroughtheInternetanddiscusshowthesebringcyberspaceintobeing

-

weconsiderthesubjectcalledthecitizenasasubjectofpower.Whilesubjecttopowerisproducedbysovereignsocieties,thesubjectofpowerisproducedbydisciplinaryandcontrolsocieties.Itisabsolutelyimportanttomakeitclearthatthecontemporarysubjectembodiesallthesethreeformsofpower.Thisisthesenseinwhichweconsiderthecitizensubjectasasubjectofpowerandasasubjectweinherit.

Qué otras formas de estar en el mundo no fueron heredadas por la tradición colonialista? ¿Podrían rastrearse etnográficamente, diálogicamente y convivialmente en otros lugares?

-

Ifwedistinguishprivacyfromanonymity,werealizethatanonymityontheInternethasspawnedanewpoliticaldevelopment.Ifprivacyistherighttodeterminewhatonedecidestokeeptoherselfandwhattosharepublicly,anonymityconcernstherighttoactwithoutbeingidentified.ThesecondconcernsthevelocityofactingthroughtheInternet.Forbetterorforworse,itisalmostpossibletoperformanactontheInternetfasterthanonecanthink.ThethirdconcernstheextensityofactingthroughtheInternet.ThenumberofaddresseesanddestinationsthatarepossibleforactingthroughtheInternetisstaggering.So,too,aretheboundaries,borders,andjurisdictionsthatanactcantraverse.Thefourthconcernstraceability.IfitisperformedontheInternet,anactcanbetracedinwaysthatarepracticallyimpossibleoutsidetheInternet.Takentogether,anonymity,velocity,extensity,andtraceabilityarequestionsthatareresignifiedbybodiesactingthroughtheInternet

-

Itistritetosay,butbeinganAmericancitizeninNewYorkisdifferentfrombeinganIraniancitizeninTehranandnotequivalentregardlessofhumanrightsconventions.Second,theboundariesofwhatissayableanddoableandthustheperformativityofbeingcitizensareradicallydifferentin,say,TunisandMadrid.Finally,theimaginaryforceofactingasacitizeninAthenshasaradicallydifferenthistorythanithas,say,inIstanbul.ThesecomplexitiesanddifferentiationscometomakeahugedifferenceinhowcitizensubjectsuptakecertainpossibilitiesandactandorganizethemselvesthroughtheInternet.

Hay ejercicios conviviales, vinculados al territorio, pero no confinados por las leyes particulares del país, en lo referido a la creación de software libre y contenidos abiertos. Sin embargo, la fuerza del estado se hace presente en casos como los de Basil, donde su activismo lo llevo a la muerte.

-

Afourthgroup,inwhichFuchsseeshimself,arguesthattheobjectiveconditionsthatledpeopletoprotestfoundmechanismsforexpressingsubjectivepositions,therebyhelpingorganizetheseprotests.[83]ByemphasizingadifferencebetweentheInternetingeneralandsocialmedia,FuchsidentifiesthreedimensionsofInternetusage,especiallybytheOccupymovement:buildingasharedimaginaryofthemovement,communicatingitsideastotheworldoutside,andengaginginintensecollaboration.[84]Fuchsalsohelpfullydevelopsamuchwiderlistofplatformsusedbythemovementratherthandumpingthemallintoanall-encompassingcategoryof‘socialmedia’.

Ver https://hyp.is/R5PndKU_EeeMGeOQsHFMbw. Es el mismo Fuchs de mi marco teórico?

-

Althoughalloftheseprotestswerestagedwithinrelativelythesameperiod,thereweresignificantdifferences,asonewouldexpect,forthereasons,methods,reactions,andeffectsoftheseacts.Yetitisfairtosaythattheyallsharedtwoqualities:alltheseactswerestagedinsquaresandstreetsandwerevaryinglyenactedthroughtheInternet.[81]Thishasresultedinnumerousinterpretationsoftherelationbetweenthetwo:squaresandsocialmedia.ItisquiteunfortunateattheoutsetthattheinterpretivedebatesabouttheimportanceoftheInternetinthestagingoftheseactshavebeenframedintermsof‘socialmedia’.

El vínculo entre la plaza pública y las redes sociales populares, es efectivamente desafortunado, pues estas últimas se parecen más a centros comerciales, que a plazas públicas. Puede ĺa plaza pública reconfigurar las redes sociales en espacios como Ocuppy y 15M, donde hay largas acampadas que reconfigurarías las prácticas respecto a los artefactos virtuales que ayudaron a articular los encuentros presenciales?

-

Butbeforeweproceed,letusnotethatwewillnotcontinuetousethelanguageofconceived,perceived,andlivedspace.Instead,wewillusethesamecategorieswehaveintroducedtodiscussthreeforcesofsubjectivationthatbringcitizensubjectsintobeing:legality,performativity,andimaginary.

The parallel is not perfect, but it will serve our purposes of maintaining a grip on the complexities of cyberspace as distinct from other spaces while approaching it from the perspective of acts that constitute it.

-

Havingrecognizedthatspaceexistsinvariousregisters,scholarsalsostudysuchspacesascultural,social,legal,economic,orpoliticalspaces.Theirassumptionisnotthatsuchspacesexistasseparateandindependentfromspacespeopleinhabit,buttheseareanalyticalmeanstoconcentrateonasubsetofrelationsthatconstitutesuchspacesfordeeperunderstandingofhowpeopleinhabit,say,aculturalspace,whichissimultaneouslyyetasynchronouslyaconceived,perceived,andlivedspace.

La descripción de los espacios hacker y maker podría conectarse con esta descripción.

-

FollowingHenriLefebvre,atleastthreeregistersofspaceshavebeenelaborated:conceivedspace,perceivedspace,andlivedspace.[76]Theessentialpointisthatinhabitingspacesinthreeregisters,weexperienceourbeing-in-the-worldthroughsimultaneousbutasynchronousregisters.Subjectsinhabitconceivedspacessuchasobjectifyingpracticesthatcode,recode,present,andrepresentspacetorenderitasalegibleandintelligiblespaceofhabitation.Peopleinhabitperceivedspacessuchassymbolicrepresentationsofspacethatguideourimaginativerelationshiptoit.Subjectsalsoinhabitlivedspacesthroughthingstheydoinorbyliving.Livedspacesarethespacesthroughwhichsubjectsact.Thesethreeregistersofspacearedistinctyetoverlappingbutalsointeracting:byinhabitingthem,wemakethem.

-

Deleuzethinksthat,bycontrast,incontrolsocieties‘thekeythingisnolongerasignatureornumberbutacode:codesarepasswords,whereasdisciplinarysocietiesareruled...byprecepts.’[67]Heobservesthat‘thedigitallanguageofcontrolismadeupofcodesindicatingwhetheraccesstosomeinformationshouldbeallowedordenied.’[68]ForDeleuze,controlsocietiesfunctionwithanewgenerationofmachinesandwithinformationtechnologyandcomputers.Forcontrolsocieties,‘thepassivedangerisnoiseandtheactive[dangersare]piracyandviralcontamination.

[...] For Deleuze, ‘[i]t’s true that, even before control societies are fully in place, forms of delinquency or resistance (two different things) are also appearing. Computer piracy and viruses, for example, will replace strikes and what the nineteenth century called “sabotage” (“clogging” the machinery).’

Otras formas de contestación pueden referirse a la creación de narrativas alternativas usando las mismas herramientas que crean las estructuras de control.

-

Deleuzewasnowconvincedthat‘[w]e’removingtowardcontrolsocietiesthatnolongeroperatebyconfiningpeoplebutthroughcontinuouscontrolandinstantcommunication.’[65]Thespaceofcontrolsocietieswasdiffuseanddispersedanddecisivelycyberneticinitsmodesofgovernment.

-

Thespacesthatsovereignpowerproducescorrespondtosuchstrategiesandtechnologiesofexclusion:expulsion,prohibition,banishment,eviction,exile,anddeportationaresuchexamples.Bycontrast,beingasubjectofpowermobilizesstrategiesandtechnologiesofdiscipline,whichrequiresubmissionbutopenuppossibilitiesofsubversion.Thespacesthatdisciplinarypowerproducesareappropriatetosuchstrategiesandtechnologiesofdiscipline:asylums,camps,andbarracksbutalsohospitals,prisons,schools,andmuseumsasspacesofconfinement.Eachofthesespacesisaspaceofcontestation,competitiveandsocialstrugglesinandthroughwhichcertainformsofknowledgeareproducedinenunciationsthatperformsubjects.Neitherspacesofexclusionnorspacesofdisciplinearestaticorcontainerspaces.Theyaredynamicandrelationalspaces.Thereareno‘physical’spacesseparatefrompowerrelationsandnopowerrelationsthatarenotembeddedinspatializingstrategiesandtechnologiesofpower.

La idea de un hackerspace como un tercer espacio, donde se juegan dinámicas de poder, como en todos, pero éste es transitorio, meritocrático, contestable, incluso a pesar de la falta de estructura evidente del mismo espacio. Como otros espacios, dicha contestación requiere saber los rituales del espacio y sus lenguajes. Tal contestación no tiene por qué tomar una forma confrontacional y puede ocurrir simplemente a través de la creación de alianzas transitorias y comunidades de práctica que eligen unas tecnologías y no otras. Incluso, prácticas como el Data Week dan la posibilidad de contestar esta práctica particular, al explicitar los saberes y materialidades que la constituyen.

-

Deibertrightlyarguesthat‘althoughcyberspacemayseemlikevirtualreality,it’snot.EverydeviceweusetoconnecttotheInternet,everycable,machine,application,andpointalongthefibre-opticandwirelessspectrumthroughwhichdatapassesisapossiblefilteror“chokepoint,”agreyareathatcanbemonitoredandthatcanconstrainwhatwecancommunicate,thatcansurveilandchokeoffthefreeflowofcommunicationandinformation.’[59]NotonlydoesthismeanthattheInternethasmaterialeffectssuchasdatacentres,serverclusters,andcode,thoughthisiscertainlytrueandtherearestudiesaboutthesematerialforms.

-

Ratherthanunderstandingcyberspaceasaseparateandindependentspace,weinterpretitasaspaceofrelations.Putdifferently,DonnaHaraway’sCyborgManifesto(1984),whichisnotaboutthethenincipientInternetbutabouttheinterconnectednessofhumansandmachines,isjustasrelevanttoourageoftheInternetthroughwhichwebothsayanddothings.

-

Ifthecomputerizationofsocietyraisessuchquestions,theanalysisoftheproduction,dissemination,andlegitimationofknowledge,onwhichithasaprofoundeffect,cannotberestrictedtounderstandingcomputerizationascommunicationorcomputer-mediatedcommunication.Rather,theobjectofinvestigationoughttobelanguagegamesthatbecamepossiblethroughwhatLyotardsawasnetworkedcomputers

-

WhatwefindinLyotard—albeitinincipientform—isthatratherthanconceivingaseparateandindependentspace,thepointistorecognizethatpowerrelationsincontemporarysocietiesarebeingincreasinglymediatedandconstitutedthroughcomputernetworksthateventuallycametobeknownastheInternet.

-

Sincethemeansofproduction,dissemination,andlegitimationofknowledgeprincipallyinvolveslanguage,Lyotardsawlanguageasthemainsiteofsocialstruggle.Itisnotsurprising,then,thatLyotardwasattractedtoLudwigWittgensteinandJ.L.Austintodevelopamethodofunderstandinglanguageasameansofsocialstruggle.

-

WehavealreadycharacterizedcyberspaceasaspaceofrelationsbetweenandamongbodiesactingthroughtheInternet.Wenotedearlierthat1984wasthebirthoftheconceptofcyberspace.Yetduringtheverysameyear,amuchlessknownwork,orrather,aworkknownmuchmoreforitstitle,Jean-FrançoisLyotard’sThePostmodernCondition(1984),appeared.

[...] We want to revisit both Lyotard’s substantive argument and his method because, writing before the concept of cyberspace, his starting point is not an ostensibly existing space but changing social relations through computerization.

-

Wedisagreewiththisviewofcode.AlthoughwegatherfromLessigandotherscholarssuchasRonDeibertandJulieCohentheimportanceofcode,wecannotagreethatcodecanordoeshavesuchadetermininginfluence.[45]Wewill,however,explainthislaterinchapter3,wherewediscussinmoredetailtheimportanceoflanguageandtheirreducibledifferencesbetweenspeech,writing,andcode.Fornow,wewanttoemphasizethatifweareboundtousetheconcept‘cyberspace’andcompareittosomethingcalled‘real’space,we’dbetterunderstandthecomplexregistersinwhichcyberspaceexistsratherthanbeingopposedtoanostensible‘real’space.

the irreducible differences between speech, writing, and code.

-

TheanathemaforLessigisthelossofthisfreedomincyberspace.Inrealspace,governingpeoplerequiresinducingthemtoactincertainways,butinthelastinstance,peoplehadthechoicetoactthiswayorthatway.Bycontrast,incyberspaceconductisgovernedbycode,whichtakesawaythatchoice.Incyberspace,‘iftheregulatorwantstoinduceacertainbehavior,sheneednotthreaten,orcajole,toinspirethechange.Sheneedonlychangethecode—thesoftwarethatdefinesthetermsuponwhichtheindividualgainsaccesstothesystem,orusesassetsonthesystem.’[37]Thisisbecause‘codeisanefficientmeansofregulation.Butitsperfectionmakesitsomethingdifferent.Oneobeystheselawsascodenotbecauseoneshould;oneobeystheselawsascodebecauseonecandonothingelse.Thereisnochoiceaboutwhethertoyieldtothedemandforapassword;onecompliesifonewantstoenterthesystem.Inthewellimplementedsystem,thereisnocivildisobedience.’[38]WhatLessigsuggestsisthatcyberspaceisnotonlyseparateandindependentbutconstitutesanewmodeofpower.Youconstituteyourselfasasubjectofpowerbysubmittingtocode.

En este caso particular la bifurcación es política a través del código, porque otros lugares del ciberespacio pueden ser creados ejerciendo este poder de bifurcar, si se entienden los códigos.

En una charla de 2008, con Jose David Cuartas, le mencionaba cómo las libertades del software libre son teóricas, si no se entiende el código fuente de dicho software (las instrucciones con las que opera y se construye). Las prácticas alrededor del código, asi como los entornos físicos, comunitarios, simbólico y computacionales, donde dichas prácticas se dan, son importantes para alentar (o no) estas comprensiones y en últimas permitir que otros códigos den la posibilidad del disenso y de construir lugares distintos. De ahí que las infraestructuras de bolsillo sean importantes, pues estas disminuyen los costos de bifuración y construcción desde la diferencia.

-

LeavingasidetheparadoxofusinganAmericanexperienceandlanguageforcreatingauniversal‘civilizationofthemind’,thedeclarationrevealsthatcyberspaceistobeconceivednotonlyasmetaphysical(nobodiesandnomatter)butalsoasanautonomousspace

-

InthedocumentaryfilmNoMapsforTheseTerritoriesherecounts,‘[A]llIknewabouttheword“cyberspace”whenIcoinedit,wasthatitseemedlikeaneffectivebuzzword.Itseemedevocativeandessentiallymeaningless.’[31]ThisisreminiscentofNietzsche’sgenealogicalprinciplethatjustbecausesomethingcomesintobeingforonepurposedoesnotmeanthatitwillservethatpurposeforever.

[K:] Revisar este documental.

-

Cyberspaceisaspaceofsocialstrugglesandnolessormore‘real’than,say,socialspaceorculturalspace—conceptsthatalsodescriberelationsbetweenbodiesandthings.Yetthisseparationbetween‘real’spaceandcyberspaceissopervasiveandcarriesabaggagethatneedsquestioning.

-

thefigureofthecitizencannotenterintodebatesabouttheInternetasasubjectwithouthistoryandwithoutgeography—andwithoutcontradictions.Rather,acriticalapproachtothefigureofthecitizenataminimumrecognizesthatitisbothasubjecttopowerandsubjectofpowerandthatthisfigureembodiesobedience,submission,andsubversionasitsdispositions

-

Theimaginaryofcitizenshipincludesawholeseriesofstatementsandutterancesaboutwhatcitizenshipis,oughttobe,hasbeen,willhavetobe,andsoon.Theimaginaryofcitizenshipisobviouslymobilizedbyandparticipatesintheformationofthelegalityofcitizenshipanditsperformativity

-

Wehaveidentifiedthisasthecontradictionbetweensubmissionandsubversionorconsentanddissent.JacquesRancièrecapturesthisasdissensus.[27]Wewillreturntodissensusinchapter7.Second,whilearticulatingaparticulardemand(forinclusion,recognition),performingcitizenshipenactsauniversalrighttoclaimrights.Thisisthecontradictionbetweentheuniversalismandparticularismofcitizenship.

Estos reclamos por el reconocimiento han tomado diferentes formas en las prácticas del Data Week. ¿Quiénes son nuestros supuestos interlocutores? ¿Por quién queremos ser reconocidos desde nuestras prácticas alternas? Yo diría que se trata de algún tipo de configuración insitucional: empresa, academía y sobre todo gobierno, pues si bien no todos estamos en los dos primeros lugares, si es cierto que todos habitamos el territorio colombiano. Uno de los esfuerzos de la Gobernatón, por ejemplo, fue pensar una manera de reparto más equitativo de los recursos públicos entre comunidades de base diversas y no sólo en aquellas enagenadas por el discurso de la innovación.

-

First,performingcitizenshipbothinvokesandbreaksconventions.Weshallcharacterizeconventionsbroadlyassociotechnicalarrangementsthatembodynorms,values,affects,laws,ideologies,andtechnologies.Associotechnicalarrangements,conventionsinvolveagreementorevenconsent—eitherdeliberateoroftenimplicit—thatconstitutesthelogicofanycustom,institution,opinion,ritual,andindeedlaworembodiesanyacceptedconduct.Sinceboththelogicandembodimentofconventionsareobjectsofagreement,performingtheseconventionsalsoproducesdisagreement.Anotherwayofsayingthisisthattheperformativityofconductsuchasmakingrightsclaimsoftenexceedsconventions

-

‘wemakerightsclaimstocriticizepracticeswefindobjectionable,toshedlightoninjustice,tolimitthepowerofgovernment,andtodemandstateaccountabilityandintervention.’

Puede esta performatividad construir alternativas en las que no está el estado, en lugar de contraponerse a él o cuestionarlo? Qué otras configuraciones de gobernanza son posibles?

-

Ifmakingrightsclaimsisperformative,itfollowsthattheserightsareneitherfixednorguaranteed:theyneedtoberepeatedlyperformed.Theircomingintobeingandremainingeffectiverequiresperformativity.Theperformativeforceofcitizenshipremindsusthatthefigureofthecitizenhastobebroughtintobeingrepeatedlythroughacts(repertoires,declarations,andproclamations)andconventions(rituals,customs,practices,traditions,laws,institutions,technologies,andprotocols).Withouttheperformanceofrights,thefigureofthecitizenwouldmerelyexistintheoryandwouldhavenomeaningindemocraticpolitics.

-

Ifindeedweunderstandthisdynamicoftakinguppositionsassubjectivation,wethenidentifythreeforcesthroughwhichcitizensubjectscomeintobeing:legality,performativity,andimaginary.Theseareneithersequentialnorparallelbutsimultaneousandintertwinedforcesofsubjectivation

-

Whoisthenthecitizen?Balibarsaysthatthecitizenisapersonwhoenjoysrightsincompletelyrealizingbeinghumanandisfreebecausebeinghumanisauniversalconditionforeveryone.[19]Wewouldsaythecitizenisasubjectwhoperformsrightsinrealizingbeingpoliticalbecausebecomingpoliticalisauniversalconditionforeveryone.

[...] ‘Western concepts and political principles such as the rights of [hu]man[s] and the citizen, however progressive a role they played in history, may not provide an adequate basis of critique in our current, increasingly global condition.’[20] Poster says this is so, among other things, because Western concepts arise out of imperial and colonial histories and because situated differences are as important as universal principles.[21] This contradiction of the figure of the citizen can be expressed in another paradoxical phrase: universalism as particularism.

-

Therightsthatthecitizenholdsarenottherightsofanalready-existingsovereignsubjectbuttherightsofafigurewhosubmitstoauthorityinthenameofthoserightsandactstocallintoquestionitsterms.Thisistheinescapableandinheritedcontradictionbetweensubmissionandsubversionofthefigureofthecitizenthatcanbeexpressedinaparadoxicalphrase:submissionasfreedom.

submission as freedom.

Ser sujeto de derechos en un estado (someterse al poder del mismo), implica también la posibilidad de sublevarse y pensar en otras formas de ciudadanía.

-

IfwefocusonhowpeopleenactthemselvesassubjectsofpowerthroughtheInternet,itinvolvesinvestigatinghowpeopleuselanguagetodescribethemselvesandtheirrelationstoothersandhowlanguagesummonsthemasspeakingbeings.Toputitdifferently,itinvolvesinvestigatinghowpeopledothingswithwordsandwordswiththingstoenactthemselves.ItalsomeansaddressinghowpeopleunderstandthemselvesassubjectsofpowerwhenactingthroughtheInternet.

-

Forus,thisalsomeansthatactsoftruthaffordpossibilitiesofsubversion.Beingasubjectofpowermeansrespondingtothecall‘howshouldone“governoneself”byperformingactionsinwhichoneisoneselftheobjectiveofthoseactions,thedomaininwhichtheyarebroughttobear,theinstrumenttheyemploy,andthesubjectthatacts?’[14]Indescribingthisashisapproach,Foucaultwasclearthatthe‘developmentofadomainofacts,practices,andthoughts’posesaproblemforpolitics.[15]ItisinthisrespectthatweconsidertheInternetinrelationtomyriadacts,practices,andthoughtsthatposeaproblemforthepoliticsofthesubjectincontemporarysocieties.

-

Whatdistinguishesthecitizenfromthesubjectisthatthecitizenisthiscompositesubjectofobedience,submission,andsubversion.Thebirthofthecitizenasasubjectofpowerdoesnotmeanthedisappearanceofthesubjectasasubjecttopower.Thecitizensubjectembodiestheseformsofpowerinwhichsheisimplicated,whereobedience,submission,andsubversionarenotseparatedispositionsbutarealways-presentpotentialities.

-

Butthesearenotpureforms;rather,thecitizensubjectembodiestheseaspotentialities.Beingasubjecttopowerismarkedbythecitizen’sdominationbythesovereign,andherrightsderivefromthatwhichisgiventoherbythe(patriarchal)sovereign.Beingasubjectofpowermeansbeinganagentofpower,evenifthisrequiressubmission.

-

asubjectisacompositeofmultipleforces,identifications,affiliations,andassociations.Thesubjectisdividedbytheseelementsratherthanbytraditionandmodernity.Italsoassertsthatasubjectisasiteofmultipleformsofpower(sovereign,disciplinary,control)thatembodiescompositedispositions(obedience,submission,subversion).

-

thatquestiontheassumptionthatcitizenshipismembershipinonlyanation-state

[...] Rather, critical citizenship studies often begins with the citizen as a historical and geographic figure—a figure that emerged in particular historical and geographical configurations and a dynamic, changing, and above all contested figure of politics that comes into being by performing politics.[7]

-

Thefieldbeginswithcitizenshipdefinedasrights,obligations,andbelongingtothenation-state.Threerights(civil,political,andsocial)andthreeobligations(conscription,taxation,andfranchise)governrelationshipsbetweencitizensandstates.Civilrightsincludetherighttofreespeech,toconscience,andtodignity;politicalrightsincludevotingandstandingforoffice;andsocialrightsincludeunemploymentinsurance,universalhealthcare,

and welfare.

-

howmultipleactorswouldneedtoresistsurveillancestrategiesbutalsothequestionofhowInternetuserswilladjusttheireverydayconduct.ItisanopenquestionwhetherInternetusers‘willcontinuetoparticipateintheirownsurveillancethroughself-exposureordevelopnewformsofsubjectivitythatismorereflexiveabouttheconsequencesoftheirownactions’

-

Givenitspervasivenessandomnipresence,avoidingorshunningcyberspaceisasdystopianasquittingsocialspace;itisalsocertainthatconductingourselvesincyberspacerequires,asmanyactivistsandscholarshavewarned,intensecriticalvigilance.Sincetherecannotbegenericoruniversalanswerstohowweconductourselves,moreorlesseveryincipientorexistingpoliticalsubjectneedstoaskinwhatwaysitisbeingcalleduponandsubjectifiedthroughcyberspace.Inotherwords,toreturnagaintotheconceptualapparatusofthisbook,thekindsofcitizensubjectscyberspacecultivatesarenothomogenousanduniversalbutfragmented,multiple,andagonistic.Atthesametime,thefigureofacitizenyettocomeisnotinevitable;whilecyberspaceisafragileandprecariousspace,italsoaffordsopenings,momentswhenthinking,speaking,andactingdifferentlybecomepossiblebychallengingandresignifyingitsconventions.Thesearethemomentsthatwehighlighttoarguethatdigitalrightsarenotonlyaprojectofinscriptionsbutalsoenactment.

¿A qué somos llamados y cómo respondemos a ello? Esta pregunta ha sido parte tácita de lo que hacemos en el Data Week.

-

digitalactsresignifyfourpoliticalquestionsabouttheInternet

anonymity, extensity, traceability, and velocity.

El primero y el tercero ha estado permanentemente en el discurso de colectivos a los que he estado vinculado (RedPaTodos, HackBo, Grafoscopio, etc)

-

Wearguethatmakingrightsclaimsinvolvesnotonlyperformativebutalsolegalandimaginaryforces.Wethenarguethatdigitalactsinvolveconventionsthatincludenotonlywordsbutalsoimagesandsoundsandvariousactionssuchasliking,coding,clicking,downloading,sorting,blocking,andquerying.

-

WedevelopourapproachtobeingdigitalcitizensbydrawingonMichelFoucaulttoarguethatsubjectsbecomecitizensthroughvariousprocessesofsubjectivationthatinvolverelationsbetweenbodiesandthingsthatconstitutethemassubjectsofpower.WefocusonhowpeopleenactthemselvesassubjectsofpowerthroughtheInternetandatthesametimebringcyberspaceintobeing.Wepositionthisunderstandingofsubjectivationagainstthatofinterpellation,whichassumesthatsubjectsarealwaysandalreadyformedandinhabitedbyexternalforces.Rather,wearguethatcitizensubjectsaresummonedandcalledupontoactthroughtheInternetand,assubjectsofpower,respondbyenactingthemselvesnotonlywithobedienceandsubmissionbutalsosubversion.

-

whenweconsiderTwitter,forinstance,wecanask:Howdoconventionssuchasmicrobloggingplatformsconfigureactionsandcreatepossibilitiesfordigitalcitizenstoact?

Es curioso que los autores también se hayan enfocado en esta plataforma, como lo hemos hecho en los Data Week de manera reiterada.

-

citizenshipasasiteofcontestationorsocialstruggleratherthanbundlesofgivenrightsandduties.[41]Itisanapproachthatunderstandsrightsasnotstaticoruniversalbuthistoricalandsituatedandarisingfromsocialstruggles.Thespaceofthisstruggleinvolvesthepoliticsofhowwebothshapeandareshapedbysociotechnicalarrangementsofwhichweareapart.Fromthisfollowsthatsubjectsembodyboththematerialandimmaterialaspectsofthesearrangementswheredistinctionsbetweenthetwobecomeuntenable.[42]Whowebecomeaspoliticalsubjects—orsubjectsofanykind,forthatmatter—isneithergivenordeterminedbutenactedbywhatwedoinrelationtoothersandthings.Ifso,beingdigitalandbeingcitizensaresimultaneouslytheobjectsandsubjectsofpoliticalstruggl

-

Soratherthandefiningdigitalcitizensnarrowlyas‘thosewhohavetheabilitytoread,write,comprehend,andnavigatetextualinformationonlineandwhohaveaccesstoaffordablebroadband’or‘activecitizensonline’oreven‘Internetactivists’,weunderstanddigitalcitizensasthosewhomakedigitalrightsclaims,whichwewillelaborateinchapter2.

Estas definiciones instrumentales de ciudadanía se presentaban en proyectos del gobierno orientados al desarrollo instrumental de competencias computacionales (particularmente en la ofimática) y no en clave de derechos. Un lenguaje desde los derechos, podría no estar vinculado a la idea de estado nación.

-

Butthefigureofcyberspaceisalsoabsentincitizenship

-> But the figure of cyberspace is also absent in citizenship studies as scholars have yet to find a way to conceive of the figure of the citizen beyond its modern configuration as a member of the nation-state. Consequently, when the acts of subjects traverse so many borders and involve a multiplicity of legal orders, identifying this political subject as a citizen becomes a fundamental challenge. So far, describing this traversing political subject as a global citizen or cosmopolitan citizen has proved difficult if not contentious.

-

Toputitdifferently,thefigureofthecitizenisaproblemofgovernment:howtoengage,cajole,coerce,incite,invite,orbroadlyencourageittoinhabitformsofconductthatarealreadydeemedtobeappropriatetobeingacitizen.WhatislosthereisthefigureofthecitizenasanembodiedsubjectofexperiencewhoactsthroughtheInternetformakingrightsclaims.Wewillfurtherelaborateonthissubjectofmakingrightsclaims,butthefigureofthecitizenthatweimagineisnotmerelyabearerorrecipientofrightsthatalreadyexistbutonewhoseactivisminvolvesmakingclaimstorightsthatmayormaynotexist.

[...] This absence is evinced by the fact that the figure of the citizen is rarely, if ever, used to describe the acts of crypto- anarchists, cyberactivists, cypherpunks, hackers, hacktivists, whistle-blowers, and other political figures of cyberspace. It sounds almost outrageous if not perverse to call the political heroes of cyberspace as citizen subjects since the figure of the citizen seems to betray their originality, rebelliousness, and vanguardism, if not their cosmopolitanism. Yet the irony here is that this is exactly the figure of the citizen we inherit as a figure who makes rights claims. It is that figure that has been betrayed and shorn of all its radicality in the contemporary politics of the Internet. Instead, and more recently, the figure of the citizen is being lost to the figure of the human as recent developments in corporate and state data snooping and spying have exacerbated.

La crítica hecha a la perspectiva hacker por estar definida en oposición a lo gubernamental, no considera estos espacios donde lo hacker se ha adelantado al estado (Ley De Software Libre), pensando derechos nuevos y nuevos escenarios de lo convivial en nuestra relación mediada por la tecnología. Por supuesto, no podemos deshacernos del contexto urbano en el que nos desemvolvemos y de la presencia totalizante del estado y las instituciones, por lo cual interactuamos con él, pero no estamos definidos exclusivamente como personas, en dicha interacción (por afirmación u oposición).

-

MarkPoster,forexample,arguesthattheseinvolvementsaregivingrisetonewpoliticalmovementsincyberspacewhosepoliticalsubjectsarenotcitizens,understoodasmembersofnation-states,butinsteadnetizens.[34]Byusingtheterm‘digitalcitizenship’asaheuristicconcept,NickCouldryandhiscolleaguesalsoillustratehowdigitalinfrastructuresunderstoodassocialrelationsandpracticesarecontributingtotheemergenceofaciviccultureasaconditionofcitizenship

-

WhatisimportanttorecognizeisthatalthoughtheInternetmaynothavechangedpoliticsradicallyinthefifteenyearsthatseparatethesetwostudies,ithasradicallychangedthemeaningandfunctionofbeingcitizenswiththeriseofbothcorporateandstatesurveillance

-

Moresignificantly,digitalstudiesspansbothsocialsciencesandhumanitiesaswellasscienceandtechnologystudiesandasksquestionsconcerningtherelationofdigitaltechnologiestosocialandculturalchange.

-

First,bybringingthepoliticalsubjecttothecentreofconcern,weinterferewithdeterministanalysesoftheInternetandhyperbolicassertionsaboutitsimpactthatimaginesubjectsaspassivedatasubjects.Instead,weattendtohowpoliticalsubjectivitiesarealwaysperformedinrelationtosociotechnicalarrangementstothenthinkabouthowtheyarebroughtintobeingthroughtheInternet.[13]WealsointerferewithlibertariananalysesoftheInternetandtheirhyperbolicassertionsofsovereignsubjects.Wecontendthatifweshiftouranalysisfromhowwearebeing‘controlled’(asbothdeterministandlibertarianviewsagree)tothecomplexitiesof‘acting’—byforegroundingcitizensubjectsnotinisolationbutinrelationtothearrangementsofwhichtheyareapart—wecanidentifywaysofbeingnotsimplyobedientandsubmissivebutalsosubversive.Whileusuallyreservedforhigh-profilehacktivistsandwhistle-blowers,weask,howdosubjectsactinwaysthattransgresstheexpectationsofandgobeyondspecificconventionsandindoingsomakerightsclaimsabouthowtoconductthemselvesasdigitalcitizens

La idea de que estamos imbrincados en arreglos socio técnicos y que ellos son deconstriuidos, estirados y deconstruidos por los hackers a través de su quehacer material también implica que existe una conexión entre la forma en que los hackers deconstruyen la tecnología y la forma en que se configuran las ciudadanías mediadas por dichos arreglos sociotécnicos.

-

Alongwiththesepoliticalsubjects,anewdesignationhasalsoemerged:digitalcitizens.Subjectssuchascitizenjournalists,citizenartists,citizenscientists,citizenphilanthropists,andcitizenprosecutorshavevariouslyaccompaniedit.[7]Goingbacktotheeuphoricyearsofthe1990s,JonKatzintroducedthetermtodescribegenerallythekindsofAmericanswhowereactiveontheInternet.[8]ForKatz,peoplewereinventingnewwaysofconductingthemselvespoliticallyontheInternetandweretranscendingthestraitjacketofatleastAmericanelectoralpoliticscaught

-

Moreover,withthedevelopmentoftheInternetofthings—ourphones,watches,dishwashers,fridges,cars,andmanyotherdevicesbeingalwaysalreadyconnectedtotheInternet—wenotonlydothingswithwordsbutalsodowordswiththings.

These connected devices generate enormous volumes of data about our movements, locations, activities, interests, encounters,and private and public relationships through which we become data subjects.

-

IftheInternet—or,moreprecisely,howweareincreasinglyactingthroughtheInternet—ischangingourpoliticalsubjectivity,whatdowethinkaboutthewayinwhichweunderstandourselvesaspoliticalsubjects,subjectswhohaverightstospeech,access,andprivacy,rightsthatconstituteusaspolitical,asbeingswithresponsibilitiesandobligations?

-

AsRonaldDeibertrecentlysuggested,whiletheInternetusedtobecharacterizedasanetworkofnetworksitisperhapsmoreappropriatenowtoseeitasanetworkoffiltersandchokepoints.[4]ThestruggleoverthethingswesayanddothroughtheInternetisnowapoliticalstruggleofourtimes,andsoistheInternetitself.

-

EvgenyMorozov’sTheNetDelusion(2011),Turkle’sownAloneTogether(2011),orJamieBartlett’sTheDarkNet(2014)strikemuchmoresombre,ifnotworried,moods.WhileMorozovdrawsattentiontotheconsequencesofgivingupdatainreturnforso-calledfreeservices,Turkledrawsattentiontohowpeoplearegettinglostintheirdevices.BartlettdrawsattentiontowhatishappeningincertainareasoftheInternetwhenpushedunderground(removedfromaccessviasearchengines)andthusgivingrisetonewformsofvigilantismandextremism.PerhapsthespyingandsnoopingbycorporationsandstatesintowhatpeoplesayanddothroughtheInternethasbecomeawatershedevent.

-

ThatformanypeopleAaronSwartz,Anonymous,DDoS,EdwardSnowden,GCHQ,JulianAssange,LulzSec,NSA,PirateBay,PRISM,orWikiLeakshardlyrequireintroductionisyetfurtherevidence.Thatpresidentsandfootballerstweet,hackersleaknudephotos,andmurderersandadvertisersuseFacebookorthatpeopleposttheirsexactsarenotsocontroversialasjustrecognizableeventsofourtimes.ThatAirbnbdisruptsthehospitalityindustryorUberthetaxiindustryistakenforgranted.ItcertainlyfeelslikesayinganddoingthingsthroughtheInternethasbecomeaneverydayexperiencewithdangerouspossibilities.

Tags

- disenso

- privacy

- anonimato

- ciberespacio

- enactive citizenship

- contradicciones

- infraestructuras de bolsillo

- vigilantismo

- tesis: recomendaciones

- ciudadanías otras

- vigilance

- microblogging

- tesis

- sumisión

- Kittler

- ciudadanía

- estado-nación

- governance

- tesis: hackerspaces

- distopia

- bifurcación

- definition

- diálogo de materialidades

- digital acts

- subversión

- QOTD

- dispocisiones

- obediencia

- trazabilidad

- prácticas

- materialidades

- poder soberano

- digital studies

- autocensura

- imbricación

- amoldable

- hackeable

- self governance

- velocidad

- protesta

- convivialidad

- bienes comunes

- alcance

- hackerspaces

- data week

- computerization

- derechos

- politics

- espacios

- poder

- infraestructura

- juegos de lenguaje

- cibernética

- data activism

- kanban: por hacer

- forces of subjectivation

- imaginación

- dicotomías

- diversidad

- self description

- popularización

- tesis: resultados

- comunidad de práctica

- subjetividades

- self empowerment

- tesis: marco teórico

- performance

- self referential

- sujeto

- digital citizenship

- idea clave

- lenguaje

- poder disciplinario

- repolitización

- control

- contestación

Annotators

-

-

www.thesociologicalreview.com www.thesociologicalreview.com

-

Theoretically informed sociological analyses of digital life can challenge the often implicit assumptions of those approaches which reinscribe divisions between humans and technologies, online and offline lives, agency and structure, and freedom and control. While these may be old dichotomies for some, they continue to have force and need to be challenged.

-

While much attention is reserved for whistleblowers and hactivists as the vanguards of Internet rights, there are many more anonymous political subjects of the Internet who are not only making rights claims by saying things but also by doing things through the Internet.

-

Like other social spaces that sociologists study, cyberspace is not designed and arranged and then experienced by passive subjects. Like the physical spaces of cities that geographers have long studied, it is a space that is bought into being by citizen subjects who act in ways that submit to but also at the same time go beyond and transgress the conventions of the Internet. In doing so they are not simply obedient and submissive but also subversive and participate in the making of and rights claims to cyberspace through their digital acts.

Interesante la idea de construir mapas de esas cibergeografías. Esta podría ser la cita para el capítulo de visualizaciones.

-

Such a conception moves us away from how we are being ‘liberated’ or ‘controlled’ to the complexities of ‘acting’ through the Internet where much of what makes it up is seemingly beyond the knowledge and consent of citizen subjects. To be sure, one cannot act in isolation but only in relation to the mediations, regulations and monitoring of the platforms, devices, and algorithms or more generally the conventions that format, organize and order what we do, how we relate, act, interact, and transact through the Internet. But it is here between and among these distributed relations that we can identify a space of possibility—a cyberspace perhaps—that is being brought into being by the acts of myriad subjects.

-

The problem is that popular critics have become too concerned about the Internet creating obedient subjects to power rather than understanding that it is also creating submissive subjects of power who are potentially and demonstrably capable of subversion. I believe that addressing the question I posed at the beginning requires revisiting the question of the (political) subject. By reading Michel Foucault, Etienne Balibar conceived of the citizen as not merely a subject to power or subject of power but as embodying both. Balibar argued that being a subject to power involves domination by and obedience to a sovereign whereas being a subject of power involves being an agent of power even if this requires participating in one’s own submission. However, it is this participation that opens up the possibility of subversion and this is what distinguishes the citizen from the subject: she is a composite subject of obedience, submission, and subversion where all three are always-present dynamic potentialities.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

. Fellows particularly advocate for improved transparency and improved effectiveness of local government services through open government data (Maruyama, Douglas, and Robertson 2013). After finishing the year fellows pursue a range of non- and for-profit career paths

-