Robert Hutchins, former dean of Yale Law School (1927–1929), president (1929–1945) and chancellor (1945–1951) of the University of Chicago, closes his preface to his grand project with Mortimer J. Adler by giving pride of place to Adler's Syntopicon. It touches on the unreasonable value of building and maintaining a zettelkasten:

But I would do less than justice to Mr. Adler's achievement if I left the matter there. The Syntopicon is, in addition to all this, and in addition to being a monument to the industry, devotion, and intelligence of Mr. Adler and his staff, a step forward in the thought of the West. It indicates where we are: where the agreements and disagreements lie; where the problems are; where the work has to be done. It thus helps to keep us from wasting our time through misunderstanding and points to the issues that must be attacked. When the history of the intellectual life of this century is written, the Syntopicon will be regarded as one of the landmarks in it.

—Robert M. Hutchins, p xxvi The Great Conversation: The Substance of a Liberal Education. 1952.

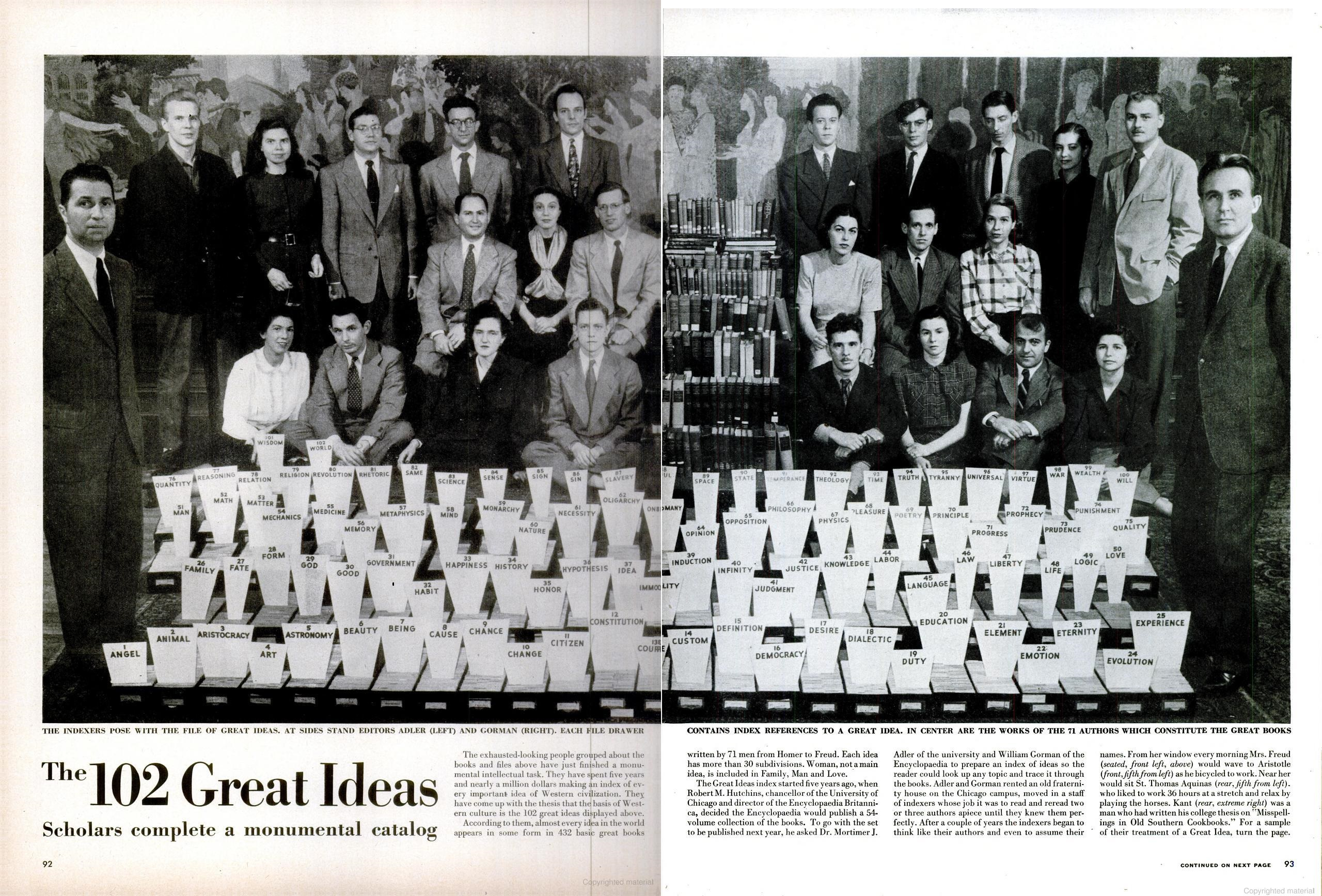

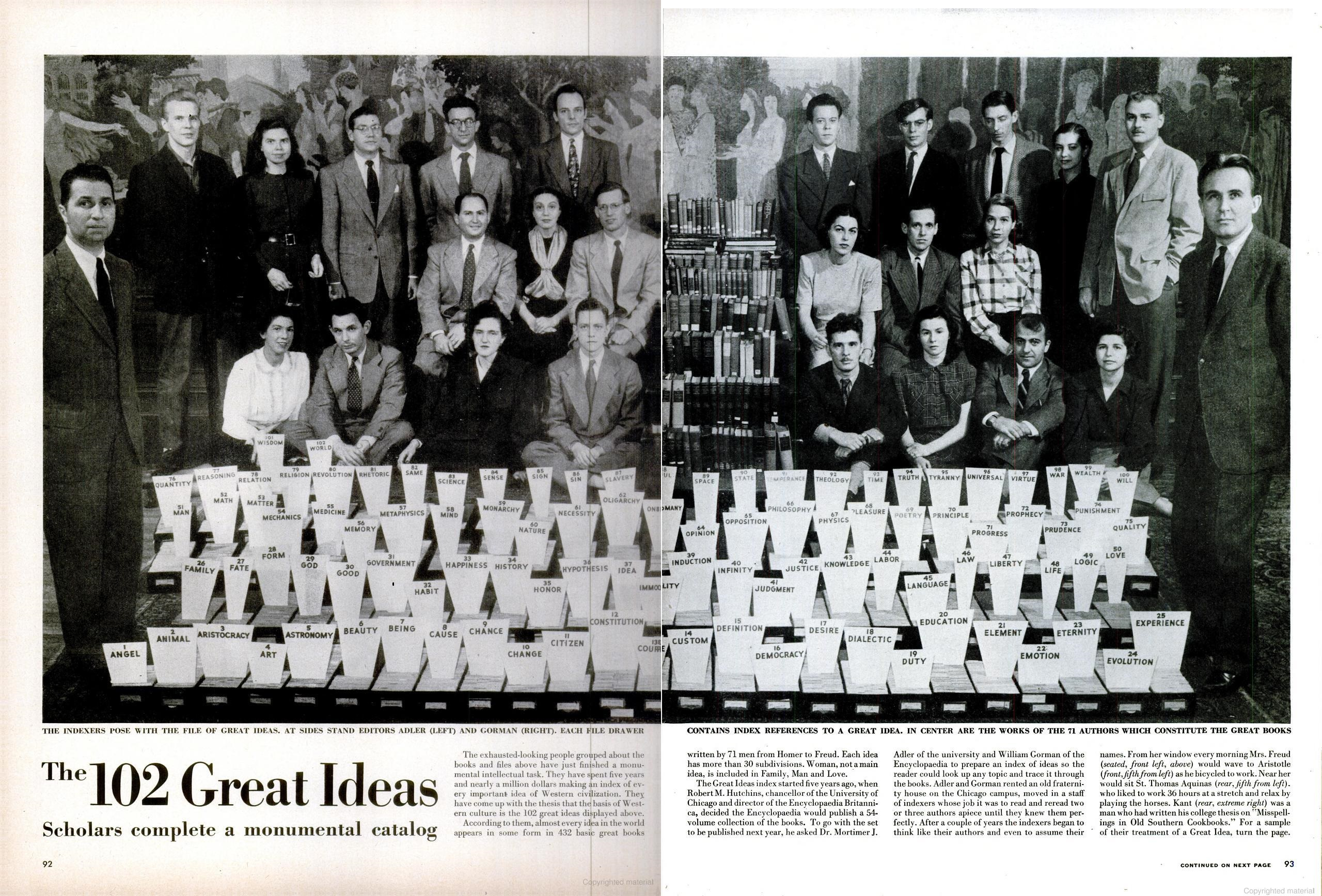

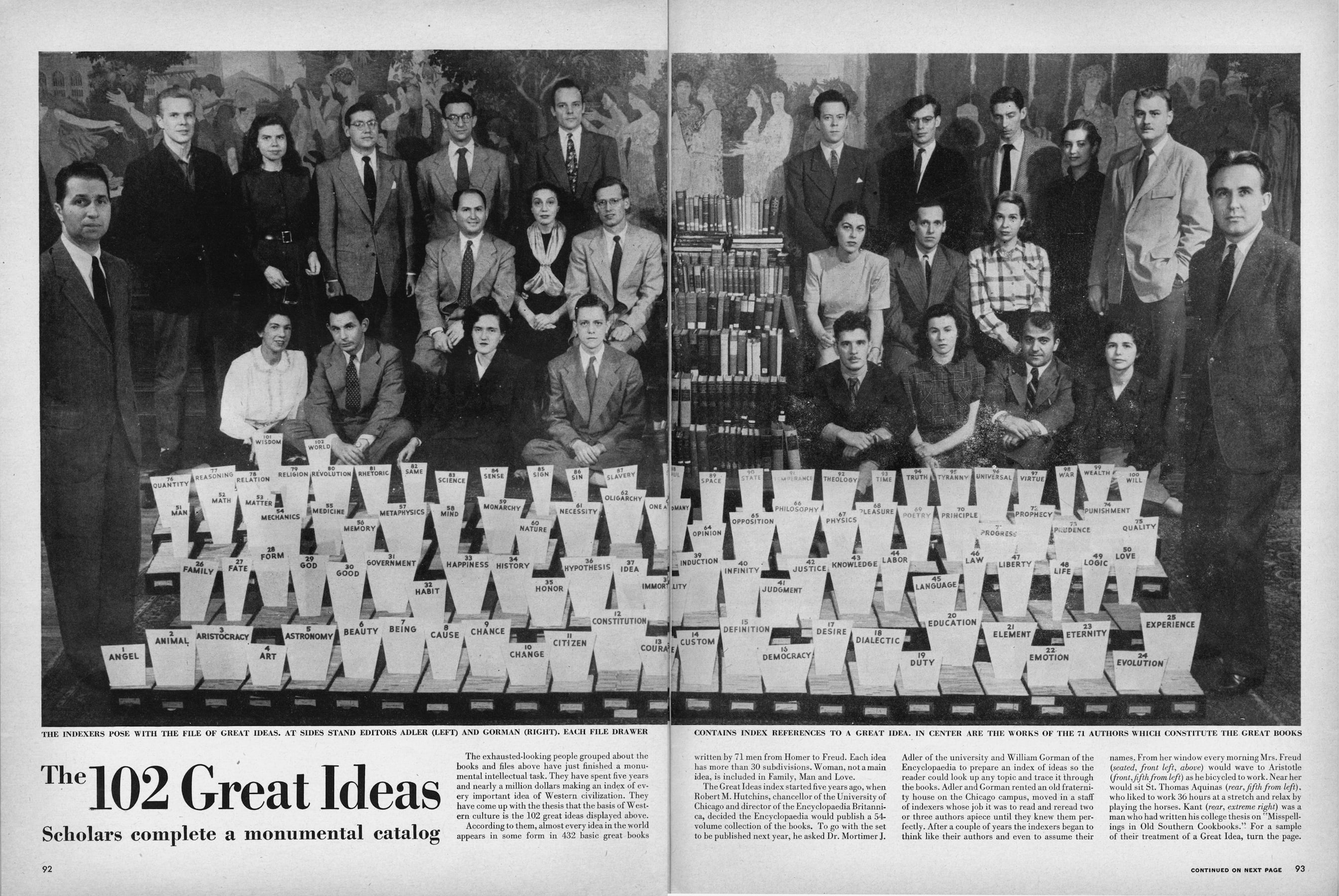

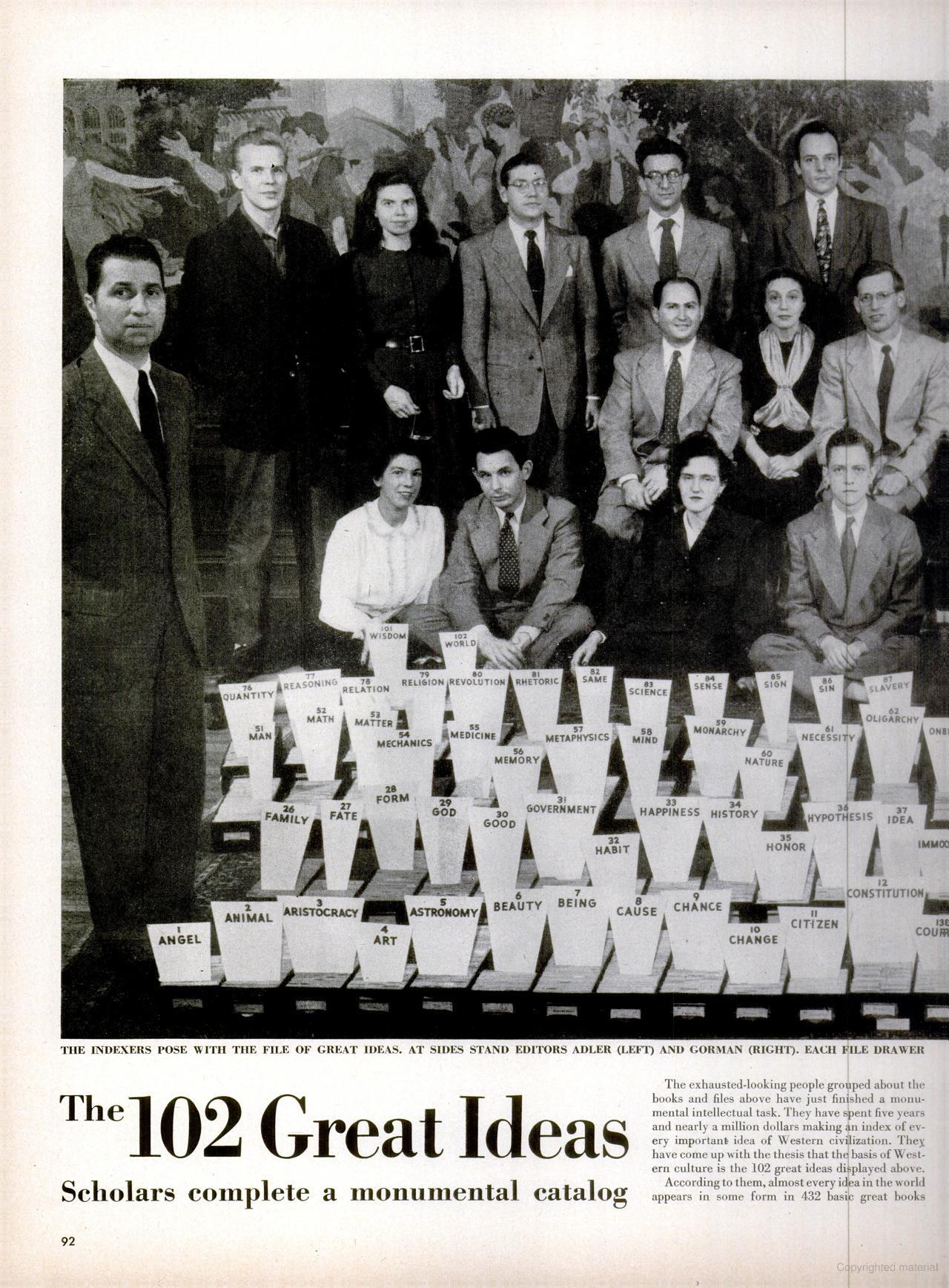

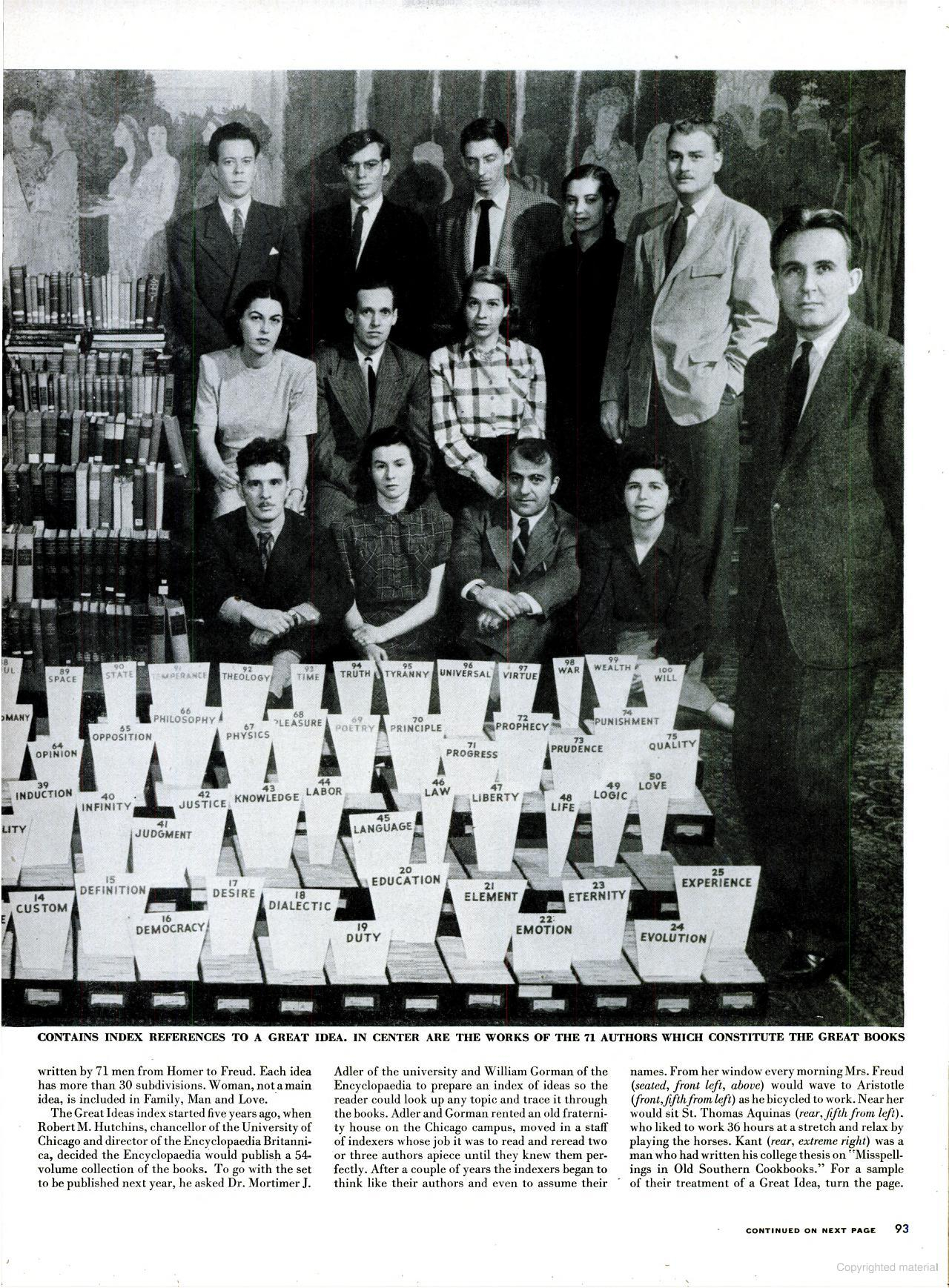

Adler's Syntopicon has been briefly discussed in the forum.zettelkasten.de space before. However it isn't just an index compiled into two books which were volumes 2 and 3 of The Great Books of the Western World, it's physically a topically indexed card index or a grand zettelkasten surveying Western culture. Its value to readers and users is immeasurable and it stands as a fascinating example of what a well-constructed card index might allow one to do even when they don't have their own yet. For those who have only seen the Syntopicon in book form, you might better appreciate pictures of it in slipbox form prior to being published as two books covering 2,428 pages:

Two page spread of Life Magazine article with the title "The 102 Great Ideas" featuring a photo of 26 people behind 102 card index boxes with categorized topical labels from "Angel" to "Will".

Two page spread of Life Magazine article with the title "The 102 Great Ideas" featuring a photo of 26 people behind 102 card index boxes with categorized topical labels from "Angel" to "Will".

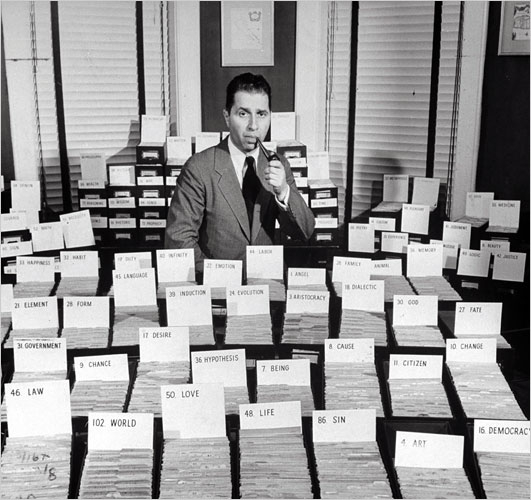

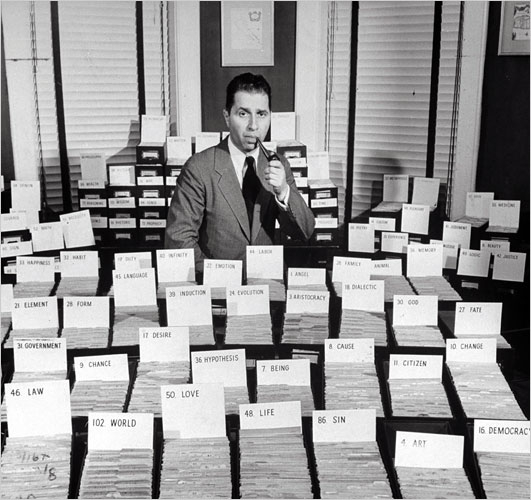

Mortimer J. Adler holding a pipe in his left hand and mouth posing in front of dozens of boxes of index cards with topic headwords including "law", "love", "life", "sin", "art", "democracy", "citizen", "fate", etc.

Mortimer J. Adler holding a pipe in his left hand and mouth posing in front of dozens of boxes of index cards with topic headwords including "law", "love", "life", "sin", "art", "democracy", "citizen", "fate", etc.

Adler spoke of practicing syntopical reading, but anyone who compiles their own card index (in either analog or digital form) will realize the ultimate value in creating their own syntopical writing or what Robert Hutchins calls participating in "The Great Conversation" across twenty-five centuries of documented human communication. Adler's version may not have had the internal structure of Luhmann's zettelkasten, but it definitely served similar sorts of purposes for those who worked on it and published from it.

References

syndication link: https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/2623/mortimer-j-adlers-syntopicon-a-topically-arranged-collaborative-slipbox/

Two page spread of Life Magazine article with the title "The 102 Great Ideas" featuring a photo of 26 people behind 102 card index boxes with categorized topical labels from "Angel" to "Will".

Two page spread of Life Magazine article with the title "The 102 Great Ideas" featuring a photo of 26 people behind 102 card index boxes with categorized topical labels from "Angel" to "Will". Mortimer J. Adler holding a pipe in his left hand and mouth posing in front of dozens of boxes of index cards with topic headwords including "law", "love", "life", "sin", "art", "democracy", "citizen", "fate", etc.

Mortimer J. Adler holding a pipe in his left hand and mouth posing in front of dozens of boxes of index cards with topic headwords including "law", "love", "life", "sin", "art", "democracy", "citizen", "fate", etc. “The Indexers pose with the file of Great Ideas. At sides stand editors [Mortimer] Adler (left) and [William] Gorman (right). Each file drawer contains index references to a Great Idea. In center are the works of the 71 authors which constitute the Great Books.” From “The 102 Great Ideas: Scholars Complete a Monumental Catalog,” Life 24, no. 4 (26 January 1948). Photo: George Skadding.

“The Indexers pose with the file of Great Ideas. At sides stand editors [Mortimer] Adler (left) and [William] Gorman (right). Each file drawer contains index references to a Great Idea. In center are the works of the 71 authors which constitute the Great Books.” From “The 102 Great Ideas: Scholars Complete a Monumental Catalog,” Life 24, no. 4 (26 January 1948). Photo: George Skadding.

(via

(via