Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Reviews):

Summary:

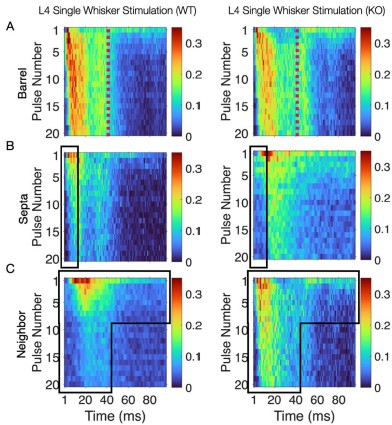

Argunşah et al. describe and investigate the mechanisms underlying the differential response dynamics of barrel vs septa domains of the whisker-related primary somatosensory cortex (S1). Upon repeated stimulation, the authors report that the response ratio between multi- and single-whisker stimulation increases in layer (L) 4 neurons of the septal domain, while remaining constant in barrel L4 neurons. This difference is attributed to the short-term plasticity properties of interneurons, particularly somatostatin-expressing (SST+) neurons. This claim is supported by the increased density of SST+ neurons found in L4 of the septa compared to barrels, along with a stronger response of (L2/3) SST+ neurons to repeated multi- vs single-whisker stimulation. The role of the synaptic protein Elfn1 is then examined. Elfn1 KO mice exhibited little to no functional domain separation between barrel and septa, with no significant difference in single- versus multi-whisker response ratios across barrel and septal domains. Consistently, a decoder trained on WT data fails to generalize to Elfn1 KO responses. Finally, the authors report a relative enrichment of S2- and M1-projecting cell densities in L4 of the septal domain compared to the barrel domain.

Strengths:

This paper describes and aims to study a circuit underlying differential response between barrel columns and septal domains of the primary somatosensory cortex. This work supports the view that barrel and septal domains contribute differently to processing single versus multi-whisker inputs, suggesting that the barrel cortex multiplexes sensory information coming from the whiskers in different domains.

We thank the reviewer for the very neat summary of our findings that barrel cortex multiplexes converging information in separate domains.

Weaknesses:

While the observed divergence in responses to repeated SWS vs MWS between the barrel and septal domains is intriguing, the presented evidence falls short of demonstrating that short-term plasticity in SST+ neurons critically underpins this difference. The absence of a mechanistic explanation for this observation limits the work’s significance. The measurement of SST neurons’ response is not specific to a particular domain, and the Elfn1 manipulation does not seem to be specific to either stimulus type or a particular domain.

We appreciate the reviewer’s perspective. Although further research is needed to understand the circuit mechanisms underlying the observed phenomenon, we believe our data suggest that altering the short-term dynamics of excitatory inputs onto SST neurons reduces the divergent spiking dynamics in barrels versus septa during repetitive single- and multi-whisker stimulation. Future work could examine how SST neurons, whose somata reside in barrels and septa, respond to different whisker stimuli and the circuits in which they are embedded. At this time, however, the authors believe there is no alternative way to test how the short-term dynamics of excitatory inputs onto SST neurons, as a whole, contribute to the temporal aspects of barrel versus septa spiking.

The study's reach is further constrained by the fact that results were obtained in anesthetized animals, which may not generalize to awake states.

We appreciate the reviewer’s concern regarding the generalizability of our findings from anesthetized animals to awake states. Anesthesia was employed to ensure precise individual whisker stimulation (and multi-whisker in the same animal), which is challenging in awake rodents due to active whisking. While anesthesia may alter higher-order processing, core mechanisms, such as short and long term plasticity in the barrel cortex, are preserved under anesthesia (Martin-Cortecero et al., 2014; Mégevand et al., 2009).

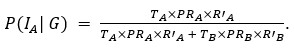

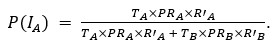

The statistical analysis appears inappropriate, with the use of repeated independent tests, dramatically boosting the false positive error rate.

Thank you for your feedback on our analysis using independent rank-based tests for each time point in wild-type (WT) animals. To address concerns regarding multiple comparisons and temporal dependencies (for Figure 1F and 4D for now but we will add more in our revision), we performed a repeated measures ANOVA for WT animals (13 Barrel, 8 Septa, 20 time points), which revealed a significant main effect of Condition (F(1,19) = 16.33, p < 0.001) and a significant Condition-Time interaction (F(19,361) = 2.37, p = 0.001). Post-hoc tests confirmed significant differences between Barrel and Septa at multiple time points (e.g., p < 0.0025 at times 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 16, 19 after Bonferroni posthoc correction), supporting a differential multi-whisker vs. single-whisker ratio response in WT animals. In contrast, a repeated measures ANOVA for knock-out (KO) animals (11 Barrel, 7 Septa, 20 time points) showed no significant main effect of Condition (F(1,14) = 0.17, p = 0.684) or Condition-Time interaction (F(19,266) = 0.73, p = 0.791), indicating that the BarrelSepta difference observed in WT animals is absent in KO animals.

Furthermore, the manuscript suffers from imprecision; its conclusions are occasionally vague or overstated. The authors suggest a role for SST+ neurons in the observed divergence in SWS/MWS responses between barrel and septal domains. However, this remains speculative, and some findings appear inconsistent. For instance, the increased response of SST+ neurons to MWS versus SWS is not confined to a specific domain. Why, then, would preferential recruitment of SST+ neurons lead to divergent dynamics between barrel and septal regions? The higher density of SST+ neurons in septal versus barrel L4 is not a sufficient explanation, particularly since the SWS/MWS response divergence is also observed in layers 2/3, where no difference in SST+ neuron density is found.

Moreover, SST+ neuron-mediated inhibition is not necessarily restricted to the layer in which the cell body resides. It remains unclear through which differential microcircuits (barrel vs septum) the enhanced recruitment of SST+ neurons could account for the divergent responses to repeated SWS versus MWS stimulation.

We fully appreciate the reviewer’s comment. We currently do not provide any evidence on the contribution of SST neurons in the barrels versus septa in layer 4 on the response divergence of spiking observed in SWS versus MWS. We only show that these neurons differentially distribute in the two domains in this layer. It is certainly known that there is molecular and circuit-based diversity of SST-positive neurons in different layers of the cortex, so it is plausible that this includes cells located in the two domains of vS1, something which has not been examined so far. Our data on their distribution are one piece of information that SST neurons may have a differential role in inhibiting barrel stellate cells versus septa ones. Morphological reconstructions of SST neurons in L4 of the somatosensory barrel cortex has shown that their dendrites and axons project locally and may confine to individual domains, even though not specifically examined (Fig. 3 of Scala F et al., 2019). The same study also showed that L4 SST cells receive excitatory input from local stellate cells) and is known that they are also directly excited by thalamocortical fibers (Beierlein et al., 2003; Tan et al., 2008), both of which facilitate.

As shown in our supplementary figure, the divergence is also observed in L2/3 where, as the reviewer also points out, where we do not have a differential distribution of SST cells, at least based on a columnar analysis extending from L4. There are multiple scenarios that could explain this “discrepancy” that one would need to examine further in future studies. One straightforward one is that the divergence in spiking in L2/3 domains may be inherited from L4 domains, where L4 SST act on. Another is that even though L2/3 SST neurons are not biased in their distribution their input-output function is, something which one would need to examine by detailed in vitro electrophysiological and perhaps optogenetic approaches in S1. Despite the distinctive differences that have been found between the L4 circuitry in S1 and V1 (Scala F et al., 2019), recent observations indicate that small but regular patches of V1 marked by the absence of muscarinic receptor 2 (M2) have high temporal acuity (Ji et al., 2015), and selectively receive input from SST interneurons (Meier et al., 2025). Regions lacking M2 have distinct input and output connectivity patterns from those that express M2 (Meier et al., 2021; Burkhalter et al., 2023). These findings, together with ours, suggest that SST cells preferentially innervate and regulate specific domains columns- in sensory cortices.

Regardless of the mechanism, the Elfn1 knock-out mouse line almost exclusively affects the incoming excitability onto SST neurons (see also reply to comment below), hence what can be supported by our data is that changing the incoming short-term synaptic plasticity onto these neurons brings the spiking dynamics between barrels and septa closer together.

The Elfn1 KO mouse model seems too unspecific to suggest the role of the short-term plasticity in SST+ neurons in the differential response to repeated SWS vs MWS stimulation across domains. Why would Elfn1-dependent short-term plasticity in SST+ neurons be specific to a pathway, or a stimulation type (SWS vs MWS)? Moreover, the authors report that Elfn1 knockout alters synapses onto VIP+ as well as SST+ neurons (Stachniak et al., 2021; previous version of this paper)-so why attribute the phenotype solely to SST+ circuitry? In fact, the functional distinctions between barrel and septal domains appear largely abolished in the Elfn1 KO.

Previous work by others and us has shown that globally removing Elfn1 selectively removes a synaptic process from the brain without altering brain anatomy or structure. This allows us to study how the temporal dynamics of inhibition shape activity, as opposed to inhibition from particular cell types. We will nevertheless update the text to discuss more global implications for SST interneuron dynamics and include a reference to VIP interneurons that contain Elfn1.

When comparing SWS to MWS, we find that MWS replaces the neighboring excitation which would normally be preferentially removed by short-term plasticity in SST interneurons, thus providing a stable control comparison across animals and genotypes. On average, VIP interneurons failed to show modulation by MWS. We were unable to measure a substantial contribution of VIP cells to this process and also note that the Elfn1 expressing multipolar neurons comprise only ~5% of VIP neurons (Connor and Peters, 1984; Stachniak et al., 2021), a fraction that may be lost when averaging from 138 VIP cells. Moreover, the effect of Elfn1 loss on VIP neurons is quite different and marginal compared to that of SST cells, suggesting that the primary impact of Elfn1 knockout is mediated through SST+ interneuron circuitry. Therefore, even if we cannot rule out that these 5% of VIP neurons contribute to barrel domain segregation, we are of the opinion that their influence would be very limited if any.

Reviewer #2 (Public Reviews):

Summary:

Argunsah and colleagues demonstrate that SST-expressing interneurons are concentrated in the mouse septa and differentially respond to repetitive multi-whisker inputs. Identifying how a specific neuronal phenotype impacts responses is an advance.

Strengths:

(1) Careful physiological and imaging studies.

(2) Novel result showing the role of SST+ neurons in shaping responses.

(3) Good use of a knockout animal to further the main hypothesis.

(4) Clear analytical techniques.

We thank the reviewer for their appreciation of the study.

Weaknesses:

No major weaknesses were identified by this reviewer. Overall, I appreciated the paper but feel it overlooked a few issues and had some recommendations on how additional clarifications could strengthen the paper. These include:

(1) Significant work from Jerry Chen on how S1 neurons that project to M1 versus S2 respond in a variety of behavioral tasks should be included (e.g. PMID: 26098757). Similarly, work from Barry Connor’s lab on intracortical versus thalamocortical inputs to SST neurons, as well as excitatory inputs onto these neurons (e.g. PMID: 12815025) should be included.

We thank the reviewer for these valuable resources that we overlooked. We will include Chen et al. (2015), Cruikshank et al. (2007) and Gibson et al. (1999) to contextualize S1 projections and SST+ inputs, strengthening the study’s foundation as well as Beierlein et al. (2003) which nicely show both local and thalamocortical facilitation of excitatory inputs onto L4 SST neurons, in contrast to PV cells. The paper also shows the gradual recruitment of SST neurons by thalamocortical inputs to provide feed-forward inhibition onto stellate cells (regular spiking) of the barrel cortex L4 in rat.

(2) Using Layer 2/3 as a proxy to what is happening in layer 4 (~line 234). Given that layer 2/3 cells integrate information from multiple barrels, as well as receiving direct VPm thalamocortical input, and given the time window that is being looked at can receive input from other cortical locations, it is not clear that layer 2/3 is a proxy for what is happening in layer 4.

We agree with the reviewer that what we observe in L2/3 is not necessarily what is taking place in L4 SST-positive cells. The data on L2/3 was included to show that these cells, as a population, can show divergent responses when it comes to SWS vs MWS, which is not seen in L2/3 VIP neurons. Regardless of the mechanisms underlying it, our overall data support that SST-positive neurons can change their activation based on the type of whisker stimulus and when the excitatory input dynamics onto these neurons change due to the removal of Elfn1 the recruitment of barrels vs septa spiking changes at the temporal domain. Having said that, the data shown in Supplementary Figure 3 on the response properties of L2/3 neurons above the septa vs above the barrels (one would say in the respective columns) do show the same divergence as in L4. This suggests that a circuit motif may exist that is common to both layers, involving SST neurons that sit in L4, L5 or even L2/3. This implies that despite the differences in the distribution of SST neurons in septa vs barrels of L4 there is an unidentified input-output spatial connectivity motif that engages in both L2/3 and L4. Please also see our response to a similar point raised by reviewer 1.

(3) Line 267, when discussing distinct temporal response, it is not well defined what this is referring to. Are the neurons no longer showing peaks to whisker stimulation, or are the responses lasting a longer time? It is unclear why PV+ interneurons which may not be impacted by the Elfn1 KO and receive strong thalamocortical inputs, are not constraining activity.

We thank the reviewer for their comment and will clarify the statement.

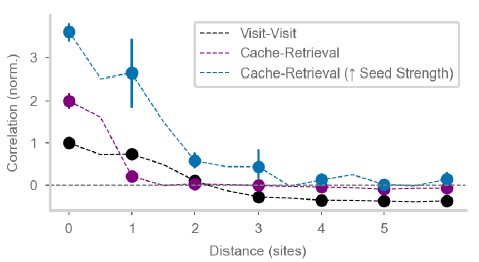

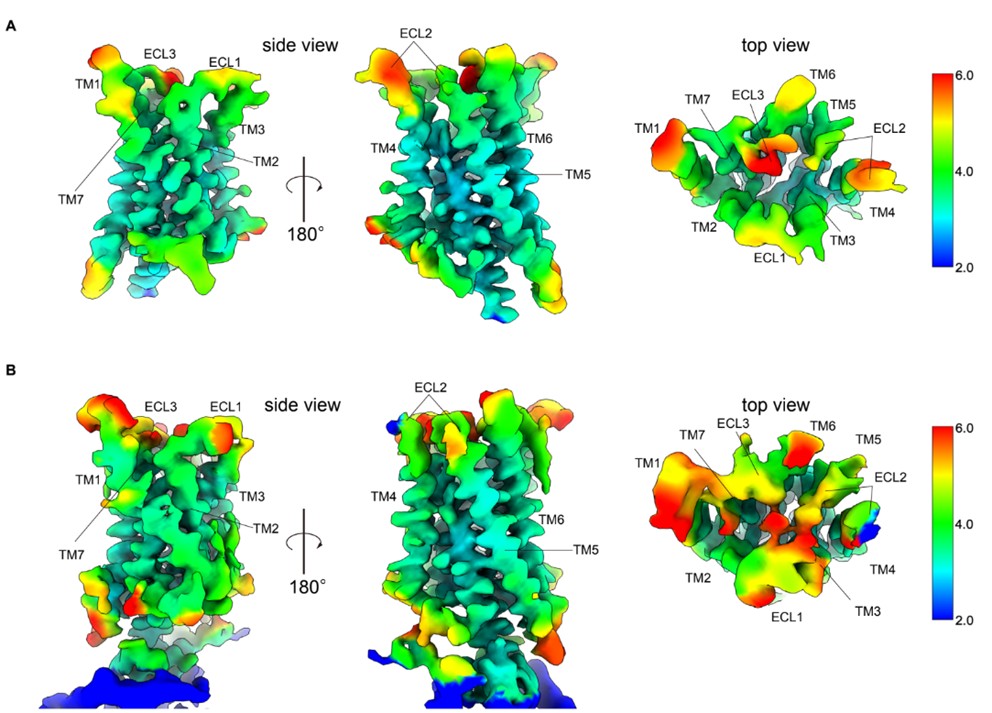

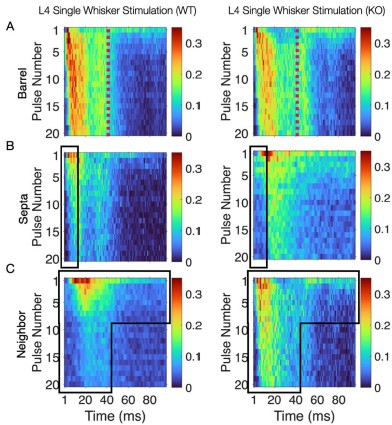

This convergence of response profiles was further clear in stimulus-aligned stacked images, where the emergent differences between barrels and septa under SWS were largely abolished in the KO (Figure 4B). A distinction between directly stimulated barrels and neighboring barrels persisted in the KO. In addition, the initial response continued to differ between barrel and septa and also septa and neighbor (Figure 4B). This initial stimulus selectivity potentially represents distinct feedforward thalamocortical activity, which includes PV+ interneuron recruitment that is not directly impacted by the Elfn1 KO (Sun et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2008). PV+ cells are strongly excited by thalamocortical inputs, but these exhibit short-term depression, as does their output, contrasting with the sustained facilitation observed in SST+ neurons. These findings suggest that in WT animals, activity spillover from principal barrels is normally constrained by the progressive engagement of SST+ interneurons in septal regions, driven by Elfn1-dependent facilitation at their excitatory synapses. In the absence of Elfn1, this local inhibitory mechanism is disrupted, leading to longer responses in barrels, delayed but stronger responses in septa, and persistently stronger responses in unstimulated neighbors, resulting in a loss of distinction between the responses of barrel and septa domains that normally diverge over time (see Author response image 1 below).

Author response image 1.

(A) Barrel responses are longer following whisker stimulation in KO. (B) Septal responses are slightly delayed but stronger in KO. (C) Unstimulated neighbors show longer persistent responses in KO.

(4) Line 585 “the earliest CSD sink was identified as layer 4…” were post-hoc measurements made to determine where the different shank leads were based on the post-hoc histology?

Post hoc histology was performed on plane-aligned brain sections which would allow us to detect barrels and septa, so as to confirm the insertion domains of each recorded shank. Layer specificity of each electrode therefore could therefore not be confirmed by histology as we did not have coronal sections in which to measure electrode depth.

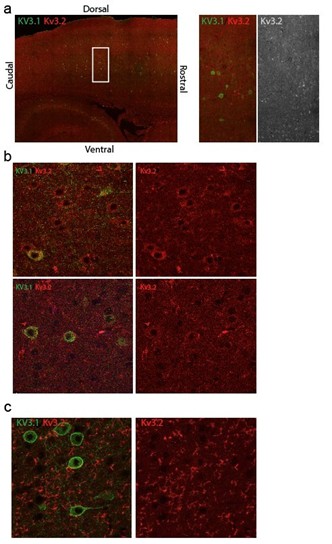

(5) For the retrograde tracing studies, how were the M1 and S2 injections targeted (stereotaxically or physiologically)? How was it determined that the injections were in the whisker region (or not)?

During the retrograde virus injection, the location of M1 and S2 injections was determined by stereotaxic coordinates (Yamashita et al., 2018). After acquiring the light-sheet images, we were able to post hoc examine the injection site in 3D and confirm that the injections were successful in targeting the regions intended. Although it would have been informative to do so, we did not functionally determine the whisker-related M1 and whisker-related S2 region in this experiment.

(6) Were there any baseline differences in spontaneous activity in the septa versus barrel regions, and did this change in the KO animals?

Thank you for this interesting question. Our previous study found that there was a reduction in baseline activity in L4 barrel cortex of KO animals at postnatal day (P)12, but no differences were found at P21 (Stachniak et al., 2023).

Reviewer #3 (Public Reviews):

Summary:

This study investigates the functional differences between barrel and septal columns in the mouse somatosensory cortex, focusing on how local inhibitory dynamics, particularly involving Elfn1-expressing SST⁺ interneurons, may mediate temporal integration of multiwhisker (MW) stimuli in septa. Using a combination of in vivo multi-unit recordings, calcium imaging, and anatomical tracing, the authors propose that septa integrate MW input in an Elfn1-dependent manner, enabling functional segregation from barrel columns.

Strengths:

The core hypothesis is interesting and potentially impactful. While barrels have been extensively characterized, septa remain less understood, especially in mice, and this study's focus on septal integration of MW stimuli offers valuable insights into this underexplored area. If septa indeed act as selective integrators of distributed sensory input, this would add a novel computational role to cortical microcircuits beyond what is currently attributed to barrels alone. The narrative of this paper is intellectually stimulating.

We thank the reviewer for finding the study intellectually stimulating.

Weaknesses:

The methods used in the current study lack the spatial and cellular resolution needed to conclusively support the central claims. The main physiological findings are based on unsorted multi-unit activity (MUA) recorded via low-channel-count silicon probes. MUA inherently pools signals from multiple neurons across different distances and cell types, making it difficult to assign activity to specific columns (barrel vs. septa) or neuron classes (e.g., SST⁺ vs. excitatory).

The recording radius (~50-100 µm or more) and the narrow width of septa (~50-100 µm or less) make it likely that MUA from "septal" electrodes includes spikes from adjacent barrel neurons.

The authors do not provide spike sorting, unit isolation, or anatomical validation that would strengthen spatial attribution. Calcium imaging is restricted to SST⁺ and VIP⁺ interneurons in superficial layers (L2/3), while the main MUA recordings are from layer 4, creating a mismatch in laminar relevance.

We thank the reviewer for pointing out the possibility of contamination in septal electrodes. Importantly, it may not have been highlighted, although reported in the methods, but we used an extremely high threshold (7.5 std, in methods, line 583) for spike detection in order to overcome the issue raised here, which restricts such spatial contaminations. Since the spike amplitude decays rapidly with distance, at high thresholds, only nearby neurons contribute to our analysis, potentially one or two. We believe that this approach provides a very close approximation of single unit activity (SUA) in our reported data. We will include a sentence earlier in the manuscript to make this explicit and prevent further confusion.

Regarding the point on calcium imaging being performed on L2/3 SST and VIP cells instead of L4. Both reviewer 1 and 2 brought up the same issue and we responded as follows. As shown in our supplementary figure, the divergence is also observed in L2/3 where we do not have a differential distribution of SST cells, at least based on a columnar analysis extending from L4. There are multiple scenarios that could explain this “discrepancy” that one would need to examine further in future studies. One straightforward one is that the divergence in spiking in L2/3 domains may be inherited from L4 domains, where L4 SST act on. Another is that even though L2/3 SST neurons are not biased in their distribution their input-output function is, something which one would need to examine by detailed in vitro electrophysiological and perhaps optogenetic approaches in S1. Despite the distinctive differences that have been found between the L4 circuitry in S1 and V1 (Scala F et al., 2019), recent observations indicate that small but regular patches of V1 marked by the absence of muscarinic receptor 2 (M2) have high temporal acuity (Ji et al., 2015), and selectively receive input from SST interneurons (Meier et al., 2025). Regions lacking M2 have distinct input and output connectivity patterns from those that express M2 (Meier et al., 2021; Burkhalter et al., 2023). These findings, together with ours, suggest that SST cells preferentially innervate and regulate specific domains -columns- in sensory cortices.

Furthermore, while the role of Elfn1 in mediating short-term facilitation is supported by prior studies, no new evidence is presented in this paper to confirm that this synaptic mechanism is indeed disrupted in the knockout mice used here.

We thank Reviewer #3 for noting the absence of new evidence confirming Elfn1’s disruption of short-term facilitation in our knockout mice. We acknowledge that our study relies on previously strong published data demonstrating that Elfn1 mediates short-term synaptic facilitation of excitatory inputs onto SST+ interneurons (Sylwestrak and Ghosh, 2012; Tomioka et al., 2014; Stachniak et al., 2019, 2023). These studies consistently show that Elfn1 knockout abolishes facilitation in SST+ synapses, leading to altered temporal dynamics, which we hypothesize underlies the observed loss of barrel-septa response divergence in our Elfn1 KO mice (Figure 4). Nevertheless, to address the point raised, we will clarify in the revised manuscript (around lines 245-247 and 271-272) that our conclusions are based on these established findings, stating: “Building on prior evidence that Elfn1 knockout disrupts short-term facilitation in SST+ interneurons (Sylwestrak and Ghosh, 2012; Tomioka et al., 2014; Stachniak et al., 2019, 2023), we attribute the abolished barrel-septa divergence in Elfn1 KO mice to altered SST+ synaptic dynamics, though direct synaptic measurements were not performed here.”

Additionally, since Elfn1 is constitutively knocked out from development, the possibility of altered circuit formation-including changes in barrel structure and interneuron distribution, cannot be excluded and is not addressed.

We thank Reviewer #3 for raising the valid concern that constitutive Elfn1 knockout could potentially alter circuit formation, including barrel structure and interneuron distribution. To address this, we will clarify in the revised manuscript (around line ~271 and in the Discussion) that in our previous studies that included both whole-cell patch-clamp in acute brain slices ranging from postnatal day 11 to 22 (P11 - P21) and in vivo recordings from barrel cortex at P12 and P21, we saw no gross abnormalities in barrel structure, with Layer 4 barrels maintaining their characteristic size and organization, consistent with wildtype (WT) mice (Stachniak et al., 2019, 2023). While we cannot fully exclude subtle developmental changes, prior studies indicate that Elfn1 primarily modulates synaptic function rather than cortical cytoarchitecture (Tomioka et al., 2014). Elfn1 KO mice show no gross morphological or connectivity differences and the pattern and abundance of Elfn1 expressing cells (assessed by LacZ knock in) appears normal (Dolan and Mitchell, 2013).

We will add the following to the Discussion: “Although Elfn1 is constitutively knocked out, we find here and in previous studies that barrel structure is preserved (Stachniak et al., 2019, 2023). Further, the distribution of Elfn1 expressing interneurons is not different in KO mice, suggesting minimal developmental disruption (Dolan and Mitchell, 2013).

Nonetheless, we acknowledge that subtle circuit changes cannot be ruled out without the usage of time-depended conditional knockout of the gene.”

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) My biggest concern is regarding statistics. Did the authors repeatedly apply independent tests (Mann-Whitney) without any correction for multiple comparisons (Figures 1 and 4)? In that case, the chances of a spurious "significant" result rise dramatically.

In response to the reviewer’s comment, we now present new statistical results by utilizing ANOVA and blended these results in the manuscript between lines 172 and 192 for WT data and 282 and 298 for Elfn1 KO data. This new statistical approach shows the same differences as we had previously reported, hence consolidating the statements made.

(2) The findings only hint at a mechanism involving SST+ neurons for how SWS and MWS are processed differently in the barrel vs septal domains. As a direct test of SST+ neuron involvement in the divergence of barrel and septal responses, the authors might consider SST-specific manipulations - for example, inhibitory chemo- or optogenetics during SWS and MWS stimulation.

We thank the reviewer for this comment and agree that a direct manipulation of SST+ neurons via inhibitory chemo- or opto-genetics could provide further supporting evidence for the main claims in our study. We have opted out from performing these experiments for this manuscript as we feel they can be part of a future study. At the same time, it is conceivable that such manipulations and depending on how they are performed may lead to larger and non-specific effects on cortical activity, since SST neurons will likely be completely shut down. So even though we certainly appreciate and value the strengths of such approaches, our experiments have addressed a more nuanced hypothesis, namely that the synaptic dynamics onto SST+ neurons matter for response divergence of septa versus barrels, which could not have been easily and concretely addressed by manipulating SST+ cell firing activity.

(3) In general, it is hard to comprehend what microcircuit could lead to the observed divergence in the MWS/SWS ratio in the barrel vs septal domain. There preferential recruitment of SST+ neurons during MWS is not specific to a particular domain, and the higher density of SST+ neurons specifically in L4 septa cannot per se explain the diverging MWS/SWS ratio in L4 septal neurons since similar ratio divergence is observed across domains in L2/3 neurons without increase SST+ neuron density in L2/3. This view would also assume that SST+ inhibition remains contained to its own layer and domain. Is this the case? Is it that different microcircuits between barrels and septa differently shape the response to repeated MWS? This is partially discussed in the paper; can the authors develop on that? What would the proposed mechanism be? Can the short-term plasticity of the thalamic inputs (VPM vs POm) be part of the picture?

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. We propose that the divergence in MWS/SWS ratios across barrel and septal domains arises from dynamic microcircuit interactions rather than static anatomical features such as SST+ density, which we describe and can provide a hint. In L2/3, where SST+ density is uniform, divergence persists, suggesting that trans-laminar and trans-domain interactions are key. Barrel domains, primarily receiving VPM inputs, exhibit short-term depression onto excitatory cells and engage PV+ and SST+ neurons to stabilize the MWS/SWS ratio, with Elfn1-dependent facilitation of SST+ neurons gradually increasing inhibition during repetitive SWS. Septal domains, in contrast, are targeted by facilitating POm inputs, combined with higher L4 SST+ density and Elfn1-mediated facilitation, producing progressive inhibitory buildup that amplifies the MWS/SWS ratio. SST+ projections in septa may extend trans-laminarly and laterally, influencing L2/3 and neighboring barrels, thereby explaining L2/3 divergence despite uniform SST+ density in L2/3. In this regards, direct laminar-dependent manipulations will be required to confirm whether L2/3 divergence is inherited from L4 dynamics. In Elfn1 KO mice, the loss of facilitation in SST+ neurons likely flattens these dynamics, disrupting functional segregation. Future experiments using VPM/POm-specific optogenetic activation and SST+ silencing will be critical to directly test this model.

We expanded the discussion accordingly.

(4) Can the decoder generalize between SWS and MWS? In this condition, if the decoder accuracy is higher for barrels than septa, it would support the idea that septa are processing the two stimuli differently.

Our results show that septal decoding accuracy is generally higher than barrel accuracy when generalizing from multi-whisker stimulation (MWS) to single-whisker stimulation (SWS), indicating distinct information processing in septa compared to barrels.

In wild-type (WT) mice, septal accuracy exceeds barrel accuracy across all time windows (150ms, 51-95ms, 1-95ms), with the largest difference in the 51-95ms window (0.9944 vs. 0.9214 at pulse 20, 10Hz stimulation). This septal advantage grows with successive pulses, reflecting robust, separable neural responses, likely driven by the posterior medial nucleus (POm)’s strong MWS integration contrasting with minimal SWS activation. Barrel responses, driven by consistent ventral posteromedial nucleus (VPM) input for both stimuli, are less distinguishable, leading to lower accuracy.

In Elfn1 knockout (KO) mice, which disrupt excitatory drive to somatostatin-positive (SST+) interneurons, barrel accuracy is higher initially in the 1-50ms window (0.8045 vs. 0.7500 at pulse 1), suggesting reduced early septal distinctiveness. However, septal accuracy surpasses barrels in later pulses and time windows (e.g., 0.9714 vs. 0.9227 in 51-95ms at pulse 20), indicating restored septal processing. This supports the role of SST+ interneurons in shaping distinct MWS responses in septa, particularly in late-phase responses (51-95ms), where inhibitory modulation is prominent, as confirmed by calcium imaging showing stronger SST+ activation during MWS.

These findings demonstrate that septa process SWS and MWS differently, with higher decoding accuracy reflecting structured, POm- and SST+-driven response patterns. In Elfn1 KO mice, early deficits in septal processing highlight the importance of SST+ interneurons, with later recovery suggesting compensatory mechanisms.

We have added Supplementary Figure 4 and included this interpretation between lines 338353.

We thank the reviewer for suggesting this analysis.

(5) It is not clear to me how the authors achieve SWS. How is it that the pipette tip "placed in contact with the principal whisker" does not detach from the principal whisker or stimulate other whiskers? Please clarify the methods.

Targeting the specific principal whisker is performed under the stereoscope.

Specifically, we have added this statement in line 628:

“We trimmed the whiskers where necessary, to avoid them touching each other and to avoid stimulating other whiskers. By putting the pipette tip very close (almost touching) to the principal whisker, the movement of the tip (limited to 1mm) would reliably move the targeted whisker. The specificity of the stimulation of the selected principal whisker was observed under the stereoscope.”

(6) The method for calculating decoder accuracy is not clearly described-how can accuracy exceed 1? The authors should clarify this metric and provide measures of variability (e.g., confidence intervals or standard deviations across runs) to assess the significance of their comparisons. Additionally, using a consistent scale across all plots would improve interoperability.

We thank the reviewer for raising this point. We have now changed the way accuracies are calculated and adopted a common scale among different plots (see updated Figure 5). We have also changed the methods section accordingly.

(7) Figure 1: The sample size is not specified. It looks like the numbers match the description in the methods, but the sample size should be clearly stated here.

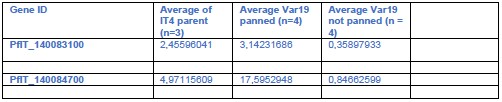

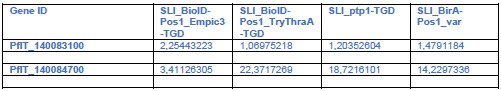

These are the numbers the reviewer is inquiring about.

WT: (WT) animals: a 280 × 95 × 20 matrix for the stimulated barrel (14 Barrels, 95ms, 20 pulses), a 180 × 95 × 20 matrix for the septa (9 Septa, 95ms, 20 pulses), and a 360 × 95 × 20 matrix for the neighboring barrel (18 Neighboring barrels, 95ms, 20 pulses). N=4 mice.

KO: 11-barrel columns, 7 septal columns, 11 unstimulated neighbors from N=4 mice.

Panels D-F are missing axes and axis labels (firing rate, p-value). Panel D is mislabeled (left, middle, and right). I can't seem to find the yellow line.

Thank you for this observation. We made changes in the figures to make them easier to navigate based on the collective feedback from the reviewers.

Why is changing the way to compare the differences in the responses to repeated stimulation between SWS and MWS?

To assess temporal accumulation of information, we compared responses to repeated single-whisker stimulation (SWS) and multi-whisker stimulation (MWS) using an accumulative decoding approach rather than simple per-pulse firing rates. This method captures domain-specific integration dynamics over successive pulses.

The use of the term "principal whisker" is confusing, as it could refer to the whisker that corresponds to the recorded barrel.

When we use the term principal whisker, the intention is indeed to refer to the whisker corresponding to the recorded barrel during single whisker stimulation. The term principal whisker is removed from Figure legend 1 and legend S1C where it may have led to ambiguity.

Why the statement "after the start of active whisking"? Mice are under anesthesia here; it does not appear to be relevant for the figure.

“After the start of active whisking” refers to the state of the barrel cortex circuitry at the time of recordings. The particular reference we use comes from the habit of assessing sensory processing also from a developmental point of view. The reviewer is correct that it has nothing to do the with the status of the experiment. Nevertheless, since the reviewer found that it may create confusion, we have now taken it out.

(8) Figure 3: The y-axis label is missing for panel C.

This is now fixed. (dF/F).

(9) Figure 4: Axis labels are missing.

Added.

Minor:

(10) Line 36: "progressive increase in septal spiking activity upon multi-whisker stimulation". There is no increase in septal spiking activity upon MWS; the ratio MWS/SWS increases.

We have changed the sentence as follows: Genetic removal of Elfn1, which regulates the incoming excitatory synaptic dynamics onto SST+ interneurons, leads to the loss of the progressive increase in septal spiking ratio (MWS/SWS) upon stimulation.

(11) Line 105: domain-specific, rather than column-specific, for consistency.

We have changed it.

(12) Lines 173-174: "a divergence between barrel and septa domain activity also occurred in Layer 4 from the 2nd pulse onward (Figure 1E)". The authors only show a restricted number of comparisons. Why not show the p-values as for SWS?

The statistics is now presented in current Figure 1E.

(13) Lines 151-153: "Correspondingly, when a single whisker is stimulated repeatedly, the response to the first pulse is principally bottom-up thalamic-driven responses, while the later pulses in the train are expected to also gradually engage cortico-thalamo-cortical and cortico-cortical loops." Can the authors please provide a reference?

We have now added the following references : (Kyriazi and Simons, 1993; Middleton et al., 2010; Russo et al., 2025).

(14) Lines 184-186: "Our electrophysiological experiments show a significant divergence of responses over time upon both SWS and MWS in L4 between barrels (principal and neighboring) and adjacent septa, with minimal initial difference". The only difference between the neighboring barrel and septa is the responses to the initial pulse. Can the author clarify?

We have now changed the sentence as follows: Our electrophysiological experiments show a significant divergence of responses between domains upon both SWS and MWS in L4. (Line 198 now)

(15) Line 214: "suggest these interneurons may play a role in diverging responses between barrels and septa upon SWS". Why SWS specifically?

We have changed the sentence as follows: These results confirmed that SST+ and VIP+ interneurons have higher densities in septa compared to barrels in L4 and suggest these interneurons may play a role in diverging responses between barrels and septa. (Line 231 now).

(16) Line 235: "This result suggests that differential activation of SST+ interneurons is more likely to be involved in the domain-specific temporal ratio differences between barrels and septa". Why? The results here are not domain-specific.

We have now revised this statement to: This result suggested that temporal ratio differences specific to barrels and septa might involve differential activation of SST+ interneurons rather than VIP+ interneurons.

(17) Lines 241-243: "SST+ interneurons in the cortex are known to show distinct short-term synaptic plasticity, particularly strong facilitation of excitatory inputs, which enables them to regulate the temporal dynamics of cortical circuits." Please provide a reference.

We have now added the following references: (Grier et al., 2023; Liguz-Lecznar et al., 2016).

(18) Lines 245-247: "A key regulator of this plasticity is the synaptic protein Elfn1, which mediates short-term synaptic facilitation of excitation on SST+ interneurons (Stachniak et al., 2021, 2019; Tomioka et al., 2014)". Is Stachniak et al., 2021 not about the role of Elf1n in excitatory-to-VIP+ neuron synapses?

The reviewer correctly spotted this discrepancy . This reference has now been removed from this statement.

(19) Lines 271-272: "Building on our findings that Elfn1-dependent facilitation in SST+ interneurons is critical for maintaining barrel-septa response divergence". The authors did not show that.

We have now changed the statement to: Building on our findings that Elfn1 is critical for maintaining barrel-septa response divergence

(20) Line 280: second firing peak, not "peal".

Thank you, it is now fixed.

(21) Lines 304-305: "These results highlight the critical role of Elfn1 in facilitating the temporal integration of 305 sensory inputs through its effects on SST+ interneurons". This claim is also overstated.

We have now changed the statement to: These results highlight the contribution of Elfn1 to the temporal integration of sensory inputs. (Line 362)

(22) Line 329: Any reason why not cite Chen et al., Nature 2013?

We have now added this reference, as also pointed out by reviewer 1.

(23) Line 341-342: "wS1" and "wS2" instead of S1 and S2 for consistency.

Thanks, we have now updated the terms.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) Figure 3D - the SW conditions are labeled but not the MW conditions (two right graphs) - they should be labeled similarly (SSTMW, VIPMW).

The two right graphs in Figure 3D represent paired SW vs MW comparisons of the evoked responses for SST and VIP populations, respectively.

(2) Figure 6 D and E I think it would be better if the Depth measurements were to be on the yaxis, which is more typical of these types of plots.

We thank the reviewer for this comment. Although we appreciate this may be the case, we feel that the current presentation may be easier for the reader to navigate, and we have hence kept it.

(3) Having an operational definition of septa versus barrel would be useful. As the authors point out, this is a tough distinction in a mouse, and often you read papers that use Barrel Wall versus Barrel Hollow/Center - operationally defining how these areas were distinguished would be helpful.

We thank the reviewer for this comment and understand the point made.

We have now updated the methods section in line 611:

DiI marks contained within the vGlut2 staining were defined as barrel recordings, while DiI marks outside vGlut2 staining were septal recordings.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

To support the manuscript's major claims, the authors should consider the following:

(1) Validate the septal identity of the neurons studied, either anatomically or functionally at the single-cell level (e.g., via Ca²⁺ imaging with confirmed barrel/septa mapping).

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion, but we feel that these extensive experiments are beyond the scope of this study.

(2) Provide both anatomical and physiological evidence to assess the possibility of altered cortical development in Elfn1 KO mice, including potential changes in barrel structure or SST⁺ cell distribution.

To address the reviewer’s point, we have now added the following to the Discussion: “Although Elfn1 is constitutively knocked out, we find here and in previous studies that barrel structure is preserved (Stachniak et al., 2019, 2023). Further, the distribution of Elfn1 expressing interneurons is not different in KO mice, suggesting minimal developmental disruption (Dolan and Mitchell, 2013). Nonetheless, we acknowledge that subtle circuit changes cannot be ruled out without conditional knockouts.”,

(3) Examine the sensory responses of SST⁺ and VIP⁺ interneurons in deeper cortical layers, particularly layer 4, which is central to the study's main conclusions.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion and appreciate the value it would bring to the study. We nevertheless feel that these extensive experiments are beyond the scope of this study and hence opted out from performing them.

Minor Comments:

(1) The authors used a CLARITY-based passive clearing protocol, which is known to sometimes induce tissue swelling or distortion. This may affect anatomical precision, especially when assigning neurons to narrow domains such as septa versus barrels. Please clarify whether tissue expansion was measured, corrected, or otherwise accounted for during analysis.

Yes, the tissue expansion was accounted during analysis for the laminar specification. We excluded the brains with severe distortion.

(2) While the anatomical data are plotted as a function of "depth from the top of layer 4," the manuscript does not specify the precise depth ranges used to define individual cortical layers in the cleared tissue. Given the importance of laminar specificity in projection and cell type analyses, the criteria and boundaries used to delineate each layer should be explicitly stated.

Thank you for pointing this out. We now include the criteria for delineating each layer in the manuscript. “Given that the depth of Layer 4 (L4) can be reliably measured due to its welldefined barrel boundaries, and that the relative widths of other layers have been previously characterized (El-Boustani et al., 2018), we estimated laminar boundaries proportionally. Specifically, Layer 2/3 was set to approximately 1.3–1.5 times the width of L4, Layer 5a to ~0.5 times, and Layer 5b to a similar width as L4. Assuming uniform tissue expansion across the cortical column, we extrapolated the remaining laminar thicknesses proportionally.”

(3) In several key comparisons (e.g., SST⁺ vs. VIP⁺ interneurons, or S2-projecting vs. M1projecting neurons), it is unclear whether the same barrel columns were analyzed across conditions. Given the anatomical and functional heterogeneity across wS1 columns, failing to control for this may introduce significant confounds. We recommend analyzing matched columns across groups or, if not feasible, clearly acknowledging this limitation in the manuscript.

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. For the comparison of SST⁺ versus VIP⁺ interneurons, it would in principle have been possible to analyze the same barrel columns across groups. However, because some of the cleared brains did not reach the optimal level of clarity, our choice of columns was limited, and we were not always able to obtain sufficiently clear data from the same columns in both groups. Similarly, for the analysis of S2- versus M1-projecting neurons, variability in the position and spread of retrograde virus injections made it difficult to ensure measurements from identical barrel columns. We have now added a statement in the Discussion to acknowledge this limitation.

(4) Figure 1C: Clarify what each point in the t-SNE plot represents-e.g., a single trial, a recording channel, or an averaged response. Also, describe the input features used for dimensionality reduction, including time windows and preprocessing steps.

In response to the reviewer’s comment, we have now added the following in the methods: In summary, each point in the t-SNE plots represents an averaged response across 20 trials for a specific domain (barrel, septa, or neighbor) and genotype (WT or KO), with approximately 14 points per domain derived from the 280 trials in each dataset. The input features are preprocessed by averaging blocks of 20 trials into 1900-dimensional vectors (95ms × 20), which are then reduced to 2D using t-SNE with the specified parameters. This approach effectively highlights the segregation and clustering patterns of neural responses across cortical domains in both WT and KO conditions.

(5) Figures 1D, E (left panels): The y-axes lack unit labeling and scale bars. Please indicate whether values are in spikes/sec, spikes/bin, or normalized units.

We have now clarified this.

(6) Figures 1D, E (right panels): The color bars lack units. Specify whether the values represent raw firing rates, z-scores, or other normalized measures. Replace the vague term "Matrix representation" with a clearer label such as "Pulse-aligned firing heatmap."

Thank you, we have now done it.

(7) Figure 1E (bottom panel): There appears to be no legend referring to these panels. Please define labels such as "B" and "S."

Thank you, we have now done it.

(8) Figure 1E legend: If it duplicates the legend from Figure 1D, this should be made explicit or integrated accordingly.

We have changed the structure of this figure.

(9) Figure 1F: Define "AUC" and explain how it was computed (e.g., area under the firing rate curve over 0-50 ms). Indicate whether the plotted values represent percentages and, if so, label the y-axis accordingly. If normalization was applied, describe the procedure. Include sample sizes (n) and specify what each data point represents (e.g., animal, recording site).

The following paragraph has been added in the methods section:

The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was computed as the integral of the smoothed firing rate (spikes per millisecond) over a 50ms window following each whisker stimulation pulse, using trapezoidal integration. Firing rate data for layer 4 barrel and septal regions in wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice were smoothed with a 3-point moving average and averaged across blocks of 20 trials. Plotted values represent the percentage ratio of multi-whisker (MW) to single whisker (SW) AUC with error bars showing the standard error of the mean. Each data point reflects the mean AUC ratio for a stimulation pulse across approximately 11 blocks (220 trials total). The y-axis indicates percentages.

(10) Figure 3C: Add units to the vertical axis.

We have added them.

(11) Figure 3D: Specify what each line represents (e.g., average of n cells, individual responses?).

Each line represents an average response of a neuron.

(12) Figure 4C legend: Same with what?". No legend refers to the bottom panels - please revise to clarify.

Thank you. We have now changed the figure structure and legends and fixed the missing information issue.

(13) Supplementary Figure 1B: Indicate the physical length of the scale bar in micrometers.

This has been fixed. The scale bar is 250um.

(14) Indicate the catalog number or product name of the 8×8 silicon probe used for recordings.

We have added this information. It is the A8x8-Edge-5mm-100-200-177-A64

References

(1) Beierlein, M., Gibson, J. R. & Connors, B. W. (2003). Two dynamically distinct inhibitory networks in layer 4 of the neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 2987–3000.

(2) Burkhalter, A., D’Souza, R. D. & Ji, W. (2023). Integration of feedforward and feedback information streams in the modular architecture of mouse visual cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 46, 259–280.

(3) Chen, J. L., Margolis, D. J., Stankov, A., Sumanovski, L. T., Schneider, B. L. & Helmchen, F. (2015). Pathway-specific reorganization of projection neurons in somatosensory cortex during learning. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1101–1108.

(4) Connor, J. R. & Peters, A. (1984). Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive neurons in rat visual cortex. Neuroscience 12, 1027–1044.

(5) Cruikshank, S. J., Lewis, T. J. & Connors, B. W. (2007). Synaptic basis for intense thalamocortical activation of feedforward inhibitory cells in neocortex. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 462–468.

(6) Dolan, J. & Mitchell, K. J. (2013). Mutation of Elfn1 in mice causes seizures and hyperactivity. PLoS One 8, e80491.

(7) Gibson, J. R., Beierlein, M. & Connors, B. W. (1999). Two networks of electrically coupled inhibitory neurons in neocortex. Nature 402, 75–79.

(8) Ji, W., Gămănuţ, R., Bista, P., D’Souza, R. D., Wang, Q. & Burkhalter, A. (2015). Modularity in the organization of mouse primary visual cortex. Neuron 87, 632–643.

(9) Martin-Cortecero, J. & Nuñez, A. (2014). Tactile response adaptation to whisker stimulation in the lemniscal somatosensory pathway of rats. Brain Res. 1591, 27–37.

(10) Mégevand, P., Troncoso, E., Quairiaux, C., Muller, D., Michel, C. M. & Kiss, J. Z. (2009). Long-term plasticity in mouse sensorimotor circuits after rhythmic whisker stimulation. J. Neurosci. 29, 5326–5335.

(11) Meier, A. M., Wang, Q., Ji, W., Ganachaud, J. & Burkhalter, A. (2021). Modular network between postrhinal visual cortex, amygdala, and entorhinal cortex. J. Neurosci. 41, 4809– 4825.

(12) Meier, A. M., D’Souza, R. D., Ji, W., Han, E. B. & Burkhalter, A. (2025). Interdigitating modules for visual processing during locomotion and rest in mouse V1. bioRxiv 2025.02.21.639505.

(13) Scala, F., Kobak, D., Shan, S., Bernaerts, Y., Laturnus, S., Cadwell, C. R., Hartmanis, L., Froudarakis, E., Castro, J. R., Tan, Z. H., et al. (2019). Layer 4 of mouse neocortex differs in cell types and circuit organization between sensory areas. Nat. Commun. 10, 4174.

(14) Stachniak, T. J., Sylwestrak, E. L., Scheiffele, P., Hall, B. J. & Ghosh, A. (2019). Elfn1induced constitutive activation of mGluR7 determines frequency-dependent recruitment of somatostatin interneurons. J. Neurosci. 39, 4461–4475.

(15) Stachniak, T. J., Kastli, R., Hanley, O., Argunsah, A. Ö., van der Valk, E. G. T., Kanatouris, G. & Karayannis, T. (2021). Postmitotic Prox1 expression controls the final specification of cortical VIP interneuron subtypes. J. Neurosci. 41, 8150–8166.

(16) Stachniak, T. J., Argunsah, A. Ö., Yang, J. W., Cai, L. & Karayannis, T. (2023). Presynaptic kainate receptors onto somatostatin interneurons are recruited by activity throughout development and contribute to cortical sensory adaptation. J. Neurosci. 43, 7101–7118.

(17) Sun, Q.-Q., Huguenard, J. R. & Prince, D. A. (2006). Barrel cortex microcircuits: Thalamocortical feedforward inhibition in spiny stellate cells is mediated by a small number of fast-spiking interneurons. J. Neurosci. 26, 1219–1230.

(18) Sylwestrak, E. L. & Ghosh, A. (2012). Elfn1 regulates target-specific release probability at CA1-interneuron synapses. Science 338, 536–540.

(19) Tan, Z., Hu, H., Huang, Z. J. & Agmon, A. (2008). Robust but delayed thalamocortical activation of dendritic-targeting inhibitory interneurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2187–2192.

(20) Tomioka, N. H., Yasuda, H., Miyamoto, H., Hatayama, M., Morimura, N., Matsumoto, Y., Suzuki, T., Odagawa, M., Odaka, Y. S., Iwayama, Y., et al. (2014). Elfn1 recruits presynaptic mGluR7 in trans and its loss results in seizures. Nat. Commun. 5, 4501.

(21) Yamashita, T., Vavladeli, A., Pala, A., Galan, K., Crochet, S., Petersen, S. S. & Petersen, C. C. (2018). Diverse long-range axonal projections of excitatory layer 2/3 neurons in mouse barrel cortex. Front. Neuroanat. 12, 33.