4,894 Matching Annotations

- Nov 2022

-

hypothes.is hypothes.is

-

hypothes.is hypothes.is

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The study aims to characterize the role of lncRNA H19 in senescence and proposes a mechanism involving CTCF and the activation of p53. The authors suggest that H19 loss induces let7b-mediated repression of EZH2, which is a critical component in the regulation of senescence-associated genes. Additionally, the authors state that H19 is required for inhibition of senescence by the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin.

The experiments appear to be performed to a high standard, and the individual observations, and conclusions about the importance of the individual players in senescence appear solid. For example, the authors convincingly show that H19 decreases in expression in aged cells/tissues and that its knockdown leads to entry into senescence. These results are consistent with recent studies in other systems (e.g., ref 38). Also, the knockdown of CTCF convincingly leads to senescence. However, these observations are largely not very surprising/novel. The premise of the manuscript is a connection between these components into a particular "axis" that regulates entry into senescence. This connection between the different regulators studied (H19, CTCF, EZH2, p53), and in particular, their specificity, which is key to the proposed "axis" remains insufficiently supported, and many of the results, unfortunately, appear to be over-interpreted.

Major comments

1. In Figure 1, the authors claim that H19 levels are reduced during aging in vitro and in vivo and that H19 levels are maintained by rapamycin treatment. To state the connection between H19 and rapamycin and its relation to aging, there is a need to show what happens in "young" cells treated with rapamycin.

Furthermore, the authors state that H19 "is essential for the inhibitory effect of rapamycin on cellular senescence". There doesn't appear to be sufficient evidence to support such a claim; additional data emphasizing the direct connection between H19 and rapamycin is needed - e.g., show that in H19-null cells rapamycin does not affect senescence.

2. CTCF is a general regulator involved in various cellular processes and supporting progression through the cell cycle; therefore, its perturbation can lead to global effects on cell health that are not necessarily related to H19. The data shown in figure 2 is insufficient to indicate a direct correlation between CTCF and H19. This will require showing that mutating specifically the CTCF binding sites near H19 affects senescence.

The same applies to the connection between H19 and let-7b shown in Figure 5. It is not very surprising that let-7b, a general antagonist of proliferation, positively regulates senescence. Here as well, the direct connection to H19 is weak. Can the authors rescue the cells that enter senescence following H19 depletion by H19 expression? If so - is this rescue capacity lost when let-7 sites are mutated? Is it possible to rescue by expressing an artificial let-7 sponge instead of H19? Otherwise, let-7b could very well be another factor related to senescence and/or regulated, but not the main mediator of the effects of H19, or part of an axis that includes H19, as proposed in the manuscript.

3. In figures 2d,3f,5i/j the authors present only representative tracks and regions from CUT&Tag-experiments, and its not clear to what extent these changes are significant when considering genome-wide data, replicates etc., and so these data are uninterpretable. This is important, as these panels are used as evidence for specific connections between members of the axis. The authors should provide a statistical test for all the regions in the genome, based on replicates, and show that these changes are significant to use these data to support their model. Otherwise, the specific connection between CTCF and H19 remains weak, and the specific change in p53 regulation of CTCF in the context of senescence is not convincing. In any case, the number of replicates and the QC of the data should be presented, and the data should be made available to the reviewers.

4. The authors state in the Discussion that the mechanism that lead to decreased H19 expression as part of the senescence program consists of two phases: an acute response driven by p53 activation and a prolonged response dictated by the loss of CTCF. There doesn't appear to be enough evidence to support this claim, as the individual experiments don't measure any such bi-phasic phenomena.

-

-

betasite.razorpay.com betasite.razorpay.com

-

{ "inquiry": "affordability", // new "amount": 100000, // mandatory "currency": "INR", // mandatory "customer": { "id": "cust_JbRkXMROZUMCVq", "contact": "+919000090000", // mandatory "alternate_contact": "9900099000", // new "imei": "6234672537253752735", // new "ip": "105.106.107.108", // new "referrer": "https://merchansite.com/example/paybill", // new "user_agent": "Mozilla/5.0", // new "addresses": [ // new { "name": "Gaurav Kumar", "line1": "SJR Cyber Laskar", "line2": "Hosur Rd", "landmark": "Adugodi", "zipcode": "560030", "city": "Bangalore", "state": "Karnataka", "contact": "9000090000", "tag": "office", "type": "shipping" }, { "name": "Gaurav Kumar", "line1": "Arena Building", "line2": "Hosur Rd", "landmark": "Adugodi", "zipcode": "560030", "city": "Bangalore", "state": "Karnataka", "contact": "9000090000", "tag": "home", "type": "billing" }, { "name": "Gaurav Kumar", "line1": "SJR Cyber Laskar", "line2": "Hosur Rd", "landmark": "Adugodi", "zipcode": "560030", "city": "Bangalore", "state": "Karnataka", "contact": "9000090000", "tag": "office", "type": "saved" } } }, { "instruments": [ { "method": "emi", "issuers": [ "HDFC" ], "types": [ "debit" ] }, { "method": "cardless_emi", "providers": [ "zestmoney", "walnut369" ] }, { "method": "paylater", "providers": [ "simpl", "lazypay" ] } ] }

please update the sample code. I have fixed it and am sending on slack

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<hr>

good call using the

tag to break up the content a bit.

-

-

meta.stackoverflow.com meta.stackoverflow.com

-

I don't think a new tag makes sense here, at least not yet.

-

creating the new tag as a synonym.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

</d>

This closing tag is unnecessary you can remove it.

-

-

addons.thunderbird.net addons.thunderbird.net

-

github.com github.com

-

<ul> <li><h3>Latest News</h3></li> <li>Octtober 1:<br/>Lorem ipsum dolor sit</li><br /> <li>September 15th:<br/>Lorem ipsum dolor sit</li><br /> <li>September 10th:<br/>Lorem ipsum dolor sit</li> </ul>

i believe there should be more space between the heading tag and the content use after it. and the text size need to bigger for the content like month names, as i see in reference image.

-

<li>Octtober 1:<br/>Lorem ipsum dolor sit</li><br />

its not look same as image reference its better if you use heading tag to make month name as heading.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<!DOCTYPE html>

missing head and closing head before the body tag

-

-

hypothes.is hypothes.is

-

https://hypothes.is/search?q=tag%3A%27etc556+etcnau%27

Randomly ran across a great tag full of education resources...

Seems to be related to this class:<br /> ETC 556 - Contexts And Methods Of Technology In Adult Education

Description: This course is designed for adult educators in the various contexts, including: higher education, military, non-profit, health and business settings. Through research, readings and collaborative activities, students will gain an understanding of various adult learning methods that include, but are not limited to, training, professional development, performance improvement, online and mobile learning. Letter grade only.

https://catalog.nau.edu/Courses/course?courseId=011553&catalogYear=2223

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

github.com github.com

-

div

comment tag again could be used to differentiate which closing div relates to which div class

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<br>

Without using the <br> tag you can achive the new line by adjusting the width of the block.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<figure> <img src="images/home.png" alt="" width="900" height="500" /> <figcaption> The Home page of the phiarchitecture website. </figcaption> </figure> <figure> <img src="images/About.png" alt="" width="900" height="500" /> <figcaption> The About page of the phiarchitecture website. </figcaption> </figure> <figure> <img src="images/Project.png" alt="" width="900" height="500" /> <figcaption> The Projrct page of the phiarchitecture website. </figcaption> </figure>

It's better to have some space between each tag in order to understand the code easy(i.e., visibility must be good).

-

-

github.com github.com

-

Copyright © 2022 All Rights Reserved North Island College Digital Design and Development

You may want to add small tag to this sentence.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

line-height: 1.8rem; padding: 10px 0; }

take off the padding on the li and give it to the a tag so you can hover less over the word to select the link, makes it better for accessibility.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This manuscript will be of interest primarily to researchers in the field of NADPH oxidases (NOXs) but also to those interested in the wider ferric reductase superfamily, also comprising members of the six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate enzymes (STEAPs). More limited interest may be expressed by investigators of ferredoxin - NADP reductases, resembling the dehydrogenase region (DH) of NOXs, expressing lesser "visibility" in the structure described in the paper. Considering the fact that NOXs are essentially electron transport machines from NADPH to dioxygen, along a multi-step redox cascade, those interested in hydride and electron transfer, at a more conceptual level, might also want to have a look at the paper. Elucidating structures of NOXs are still rare achievements, with only four published papers, so far (one coming from the group of the present main author) and, thus, any new publication profits from the aura of novelty.

Introduction<br /> This manuscript offers a detailed and in depth description of the structure of the catalytic core of the human phagocyte NADPH oxidase, NOX2, in heterodimeric association with the protein p22phox. The phagocyte NADPH oxidase is responsible for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the primary molecule of which is the superoxide radical (O2.-), derived by the one-electron reduction of molecular oxygen by NADPH. NOX2 belongs to the NOX family, consisting of 7 members (NOX 1-5, and DUOX1 and DUOX2), sharing common structural characteristics but expressing a wide variety of functions. The principal but not the only function of NOX2 is as a source of ROS for the killing of pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, protozoa) engulfed by phagocytes in the course of innate and acquired immunity.

The structures of C. stagnale NOX5, and that of murine and human DUOX1 were determined by X-ray crystallography (NOX5) and cryo-EM (DUOX1). As sources of potentially dangerous auto-toxic ROS, NOXs are subject to strict functional regulation. Whereas Nox5 and the DUOXs are regulated by Ca2+, NOXs 1, 2, and 3 are regulated by several cytosolic proteins, that associate with the Nox2-p22phox dimer forming the active O2.-generating complex. The paramount model of cytosolic regulation is Nox2 and the "dream" of structure investigators is to elucidate the structure of NOX2 in both resting and activated states.

Achievements<br /> Note: When this paper was received for review, this reviewer was not aware of any publication dealing with the structure of human Nox2. However, on October 14, 2022 a paper was published on line, dealing with the structure of Nox2 (S. Noreng et al., Structure of the core human NADPH oxidase Nox2, Nature Communications (2022)13:6079). This review will not discuss the present manuscript in relation to the paper by S. Noreng et al.

This manuscript is successful in describing the structure of the NOX2-p22phox heterodimer using cryo-EM methodology. In order to compensate for the small size of the complex, use was made of the Fab of a monoclonal anti-Nox2 antibody binding an anti-light chain tagged nanobody. In order to mimic as much as possible the milieu of NOX2-p22phox in the phagocyte membrane bilayer, the authors reconstitute the quaternary complex in a nanodisc, using soybean phosphatidylcholine (PC) and a membrane scaffold protein (MSP). To the best of my knowledge, this is the first report of studying a NOX in a nanodisc, for both function and structure. Peptidiscs were used in determining the structure of human DUOX1 by a group led by the main author of this paper, but nanodiscs offer the advantage of adding a phospholipid chosen by the investigator. The purified nanodiscs incorporating the quaternary complex led to successful structure determination of the transmembrane domain (TMD), extracellular and intracellular loops, inner and outer hemes, distances between hemes and FAD to inner heme, and a hydrophilic tunnel connecting the exterior of the cell to the oxygen-reducing center of NOX2. The structure of the dehydrogenase region (DH) was less well defined; the FAD-binding domain (FBD) was more visible than the NADPH-binding domain (NBD). The structure of p22phox and the interface between Nox2 and p22phox are well described.

The mutations in NOX2 and p22phox causative of the deficient bactericidal function in Chronic Granulomatous Disease are related in detail to the location and role of the mutated residues as revealed by the solved structure.<br /> The authors make it clear that the structure, as presented, is in the resting state. The distances between hemes are suitable for electron transfer but the distance between FAD, in the FBD, and the inner heme is too large for transfer. The poor quality of the obtained structure of the DH (especially, the NBD), even after local refinement focusing, suggests its flexibility (mobility?) relative to the TMD and that, in NOX2, the DH is "displaced" relative to the TMD, when compared to the situation in the activated (by Ca2+) DUOX1. The mobility of NBD in NOX2 also results in weak interaction with FBD, making hydride transfer from NADPH to FAD inefficient

A major achievement of the work described in this manuscript is what I believe to be the first description of the activation of recombinant NOX2-p22phox in a nanodisc, to generate O2.-, when activated by a trimeric fusion protein (trimera), consisting of the functionally important parts of the three cytosolic components, p47phox, p67phox, and Rac (see Y. Berdichevsky et al., J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22122-22139, 2007). This proves that the resting state structure of NOX2-p22phox has all that is needed to be converted to the activated state. The fact that the nature of the phospholipid in the nanodisc can be varied and that this is known to have a major effect on the affinity of the trimera for NOX2-p22phox, offers additional advantages.

Weaknesses<br /> A weakness of this, otherwise impressive work, is the difficulty for readers who are not sufficiently "structure educated" to fully understand the "displacement" of the DH of NOX2, shown in the NOX2/DUOX1 overlay (Figure 5). The meaning of "centers of mass" of FBD and FAD, in Figures 5C and 5D, respectively, is not properly explained.

Yet another weakness is the much too vague wording of the change in NOX2 conformation from the resting to the activated state by cytosolic factors as "the cytosolic factors might likely stabilize the DH of NOX2 in the "docked" conformation which is similar to that observed in the activated DUOX1 in the high-calcium state". First, the evidence from biochemical studies of NOX2 activation indicates clearly distinct targets of individual cytosolic components and not a "block" action. There is also support for the conformational change being the result of the action of a single cytosolic component (p67phox), with the other cytosolic components acting as carriers or activators of one cytosolic component by another, such as Rac-GTP acting as a carrier and inducer of a conformational change in p67phox (see J. El-Benna and P.M-C. Dang, J. Leukoc. Biol. 110, 213-215, 2021, and E. Bechor et al., J. Leukoc. Biol. 110, 219-237, 2021). Also, the concept of "docking of the DH to the TMD" seems like an oversimplification of the many locations and partners of such "docking" and ignores the possible multiple consequence of such docking. Even before the appearance of structural studies of NOXs, revealing precise distances between redox stations (NADPH-FAD; FAD-inner heme; inner heme - outer heme), as first reported for C. stagnale Nox5, by F. Magnani et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6764-6769, 2017, a shortening of the distance between an electron donor and acceptor at specific locations in the redox cascade was proposed. The most popular was the NADPH - FAD hydride transfer, based on structural work by P.A. Karplus on Ferredoxin - NADP reductases, the accepted model for the DH of NOXs.

An unfair request for an unachieved task<br /> Of course, the dream of those hoping for a structure-based response to solving the molecular mechanism of NOX activation is to see the structure of the activated NOX2 in complex with three cytosolic components. The compelling finding in the present manuscript that a nanodisc-embedded recombinant NOX2-p22phox can be activated to ROS production by the use of a [p47phox-p67phox-Rac] trimera (replacing three cytosolic components) will provoke in all the readers the wish to see the structure of such a complex. The size of the trimera with a GFP tag (108 kDa) might make the use of the anti-Nox2 Fab and anti-light chain nanobody, unnecessary. Prenylation of the trimera at the Rac moiety is bound to markedly enhance its affinity for the phospholipids in the nanodisc and is likely to generate a more stable complex, most suitable for cryo-EM (see A. Mizrahi et al., J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25485-25499, 2010).

-

-

example.com example.com

-

Is there a way to search for your replies to someone's public annotations?

Currently, they don't show up when I search my user name and the tag I used in the reply. Is there an elegant way to search for these annotations and my reply to them?

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

adriennemareebrown.net adriennemareebrown.net

-

This palpable, active, ongoing grief is a non-negotiable part of this period of immense change. Grief is one of the most beautiful and difficult ways we love. As we grieve we feel our humanity and connection to each other. Building the path from this heartbreaking present to a future where we center our collective existence in love and care is where we come in. We are the ones shining light on the lies and inconsistencies in our current reality, and we are the ones dreaming up, remembering and practicing mutual ways of being in community with each other. We are learning how to grieve without disappearing, and we are refusing to normalize this terror. We are scholars of belonging and accountability, releasing ourselves from the reductive protocols of punitive culture. We are protesting injustice wherever we find it, while forging the pathways to a justice we cocreate. We are releasing either/or thinking, and we are outgrowing every construct meant to divide and disempower us. We understand that this is an extinction point, and we are not just interested in survival – we want a just world for future generations and for the earth. Each day, we are the ones creating more possibilities. We at ESII see how this community is showing up to hold each other, to grieve, to care for each other, to practice the future together. We love you, we trust you, we grieve with you, and we change with you.

-

-

adriennemareebrown.net adriennemareebrown.net

-

adrienne maree brown 'The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.' – camus…documenting my liberation

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<img class="logo-img" src="images/dgl-logo.png" alt="DGL logo" width="80">

I agree with Sahil. I think creating a link to the homepage by placing the img inside an anchor tag would be ideal .

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<p> Tessa Warman</p>

This probably could have been an h2 tag, there will be alot of contrast between Assignment E and your name with it being a paragraph.

-

<div class="image"> <img src="images/homepageheader.png" alt="homepage"> </div>

you don't actually need the div class= "image" also I think it's missing a closing tag.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<p></p>

Not totally sure why you have an open and closed paragraph tag.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<p class="footerheading">About us:</p>

You can use h tag instead of p.

-

<p class="latestp">Our Latest projects includes:</p>

You can change this to h2 tag.

-

<div class="main-div">

You may want to change this content to article and add h2 tag, so user can understand what the content describes.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<p>Created by Janelle 30/10/2022</p>

You can use small tag to make this sentence smaller.

-

<p><strong>They can be more professional.</strong> </p>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<p><strong>Some of the images are too large and have no caption.</strong></p>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<p><strong>The most noticeable areas are not the most important.</strong></p>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<p><strong>There are too many sizes of font.</strong> </p>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<p><strong>The most noticeable areas are not the most important.</strong> </p>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<p><strong>The larger font size is not used for the heading</strong> </p>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<strong>The page elements are too distracting</strong>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<strong>The current link on the navigation menu is not clearly discernible</strong>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

<strong>The header is too large</strong>

You can use h3 tag instead of strong tag.

-

-

stackoverflow.com stackoverflow.com

-

Changing the second line to: foo.txt text !diff would restore the default unset-ness for diff, while: foo.txt text diff will force diff to be set (both will presumably result in a diff, since Git has presumably not previously been detecting foo.txt as binary).

comments for tag: undefined vs. null: Technically this is undefined (unset,

!diff) vs. true (diff), but it's similar enough that don't need a separate tag just for that.annotation meta: may need new tag: undefined/unset vs. null/set

-

-

hypothes.is hypothes.is

-

MiguelAngelLópezRodríguez

FernandoMoctezumaSoto

-

-

hub.docker.com hub.docker.com

-

Note: This repo does not publish or maintain a latest tag. Please declare a specific tag when pulling or referencing images from this repo.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<br

you can use list tag instead of using too more br tag

-

<br>

This tag is used very often.

-

Home

nav tag is good for list instead of p tag

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<p class="rights1">Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved North Island College DIGITAL Design + Development </p>

A small tag would give more context to the function of the element

-

-

annotatingdracula.commons.gc.cuny.edu annotatingdracula.commons.gc.cuny.edu

-

Kept in shorthand.

Both Jonathan and Mina keep their journals in shorthand, and yet what we read here is in complete sentences. And Dr. Seward's Diary is spoken into a phonograph. We are experiencing this text very differently from how it is created. We combined with the several posts that contain correspondence that was never opened by or delivered to the intended experience (see Unopened or Undelivered tag), there is much of this story that we experience differently from the characters within it.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<!--Fonts-->

This comment is a good idea. Just looks like a slight typo in the closing tag.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

article

might wrap this in a header tag to indicate its your title section

-

p

missing its closing tag

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<article class="homepageimagebox"> <img src="images/homepage.png" width="260" alt="photo of homepage"> </article>

I would pay attention to the semantic coding of this section. I'm not sure if a single image would make sense as an article, especially since article typically requires a heading. I would personally just tag it as a figure (that way you can also attach a caption in case it doesn't load) and if you're worried about styling apply a div.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The goal of this study was to understand the molecular mechanism of how transcription factor DUX4, which has a role in cancer, inhibits the induction of genes stimulated by interferon-gamma. The authors achieved this goal, and their results mostly support their conclusions. They found that DUX4, in their experimental model, interacts with STAT1, thereby decreasing STAT1 and Pol-II recruitment to sites of gene transcription.

The present study has many strengths: The topic is of broad interest, the findings are novel and intriguing, the experiments are well-designed and controlled, the data, with one exception, is carefully interpreted, and the manuscript is very well-written.

Two major weaknesses were identified. One is that all experiments, except Figure 6, rely on one experimental setup, which is a human skeletal muscle cell line with an integrated doxycycline-inducible transgene. The concern is that both the treatment of cells with the drug doxycycline and the fact that signaling pathways could be disrupted in this (immortalized?) cell line could lead to artifacts that skew results. Indeed, results in Figure 4C indicate that total STAT1 is completely localized in the nucleus even prior to interferon stimulation when it should be in the cytoplasm. The other weakness is the use of the DUX4-C-terminal-domain (DUX4-CTD) mutant for the majority of the mechanistic experiments. The concern here is that although the phenotype of ISG repression is observed in this truncated mutant, important regulatory domains could be missing that modulate the interaction with STAT1 or other proteins. Is the NLS added after the flag tag identical to the endogenous NLS? Related, I disagree with the interpretation of Figure 4C that "this interaction happens within the nuclei of DUX4-CTC expressing cells". The interaction could happen prior to STAT1 shuttling to the nucleus.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Note: This preprint has been reviewed by subject experts for Review Commons. Content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Referee #1

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

This manuscript reports motility characteristics and load-bearing properties of three human kinesin-6 family proteins that function during late telophase/cytokinesis of mitosis. The authors report single molecule and multiple motor motility assays, and vesicle dispersion assays for the three motors. Because the kinesin motors are important for normal division, their motility characteristics are of interest to workers in the mitosis field. However, data presentation in this manuscript could be greatly improved, along with interpretations of functional differences based on kinesin-6 motility properties.

Major points are the following:

- Quantitation and presentation of the data throughout the manuscript should be improved.

The criteria used for identifying fluorescent spots as single motors are not given. This is typically based on photobleaching experiments and fluorescence intensity measurements - the authors should show these data to validate that the motility reported is due to single motors.

A table should be included that shows the single molecule motility parameters that were analyzed and compared for the three motors, rather than just the dwell times for the assays shown in Fig. 1. Other motility characteristics should include run lengths, binding rates, detachment rates, and velocity. The percentage of time that the single motors move directionally, diffuse, or remain stationary should also be given.<br /> The authors refer to imaging rates (1 frame/50ms, p. 5), but do not state the total time of the assays, making the statements uninterpretable, as it is not clear what would be expected without knowledge of the total assay time. The authors also state that a slower imaging rate (1 frame/2 sec) was used to detect slow processive motility, but the logic underlying this statement is not clear, as a longer assay time should reveal the slow processive movement irrespective of the imaging rate. These statements should be clarified.<br /> The authors give the data for the dwell times in single motor assays and velocities in multiple motor assays as the mean + SEM, but the SD rather than SEM should be reported for these assays, given that the data are for individual single motors or individual gliding microtubules. The authors state the number of replicate experiments for the assays, but they should also state the number of data points that were obtained for each replicate. Further, they should evaluate the significance of differences in their data by giving P values obtained using appropriate statistical tests and indicate whether the differences among the motors are significant.<br /> The percentages of processive events (p. 5) are most likely dependent on the amount of inactive or denatured protein in a given preparation, rather than a motility property of the motor protein - this could be determined by analysis of whether the percentages differ from preparation to preparation of each motor and whether the mean+SD of the preparations of a given motor differs from the other motors. The statements by the authors on p. 8 that "the majority of proteins do not undergo unidirectional processive motility as single molecules but rather diffuse along the surface of the microtubule for several seconds" and "It is presently unclear why only a subset of kinesin-6 molecules are capable of directional motility (Figure 1 ..." are not meaningful, as they do not take into account the percentages of the kinesin-6 proteins that are inactivated or denatured during protein preparation.<br /> Again, given that inactive motors are produced during preparation of the proteins, it is not clear what the frequency of processive motility events means. If the authors think that the frequency of processive motility events is informative and a characteristic of each motor, they should present controls showing frequencies of processive motility events for specific well characterized motors. For example, does a control of kinesin-1 show 100% or only 95% processive motility events?<br /> For the multiple motor gliding assays, velocities are shown in Fig. 2 without controls demonstrating the dependence of the velocities on motor concentration in the assays - the gliding assays require dilution experiments to show that the velocities are within the linear range of motor concentration and do not fall within the range of higher concentrations in which motor gliding velocity is inhibited or lower motor concentrations in which the density of motors on the surface is too low to support processive movement. These control experiments of motor concentration vs velocity for the gliding assays should be shown for each of the three motors that was assayed. The authors should state whether the gliding velocities that were determined correspond to the Vmax for each of the motors that was assayed.

Again, the velocities given on p. 6 should include the SD and evaluation of the significance of the differences among the motors by obtaining P values.

Proteins for motility assays: Western blots of the purified proteins should be shown as a supplemental figure.

How are the motility characteristics of the three motors related to their spindle functions? This is the central point of the manuscript but is not clearly stated.

- Functional assays should be relevant to motor function.

Given that the kinesin-6 motors under study are mitotic spindle motors that do not normally transport vesicles, it is not clear why the authors chose to show load dependence using peroxisome and Golgi dispersion assays, rather than assays of spindle function. The authors interpret peroxisomes and Golgi to differ in dispersion load, but this appears to be based on interpretations from assays of highly processive motors, kinesin-1 and myosin V, that function in vesicle trafficking, rather than quantitative data from appropriate controls showing that peroxisomes and Golgi can be dispersed by spindle motors that bear different loads. The problems inherent in the use of these assays for spindle motors are evidenced by the authors' observations on p. 6 that MKLP1- mNG-FRB and KIF20-mNG-FRB in midbodies could not be localized to peroxisomes by rapamycin. There are no data presented showing the dependence of dispersion on protein expression/presence in the cytoplasm, making the dispersion assays difficult to interpret.

The kinesin-6 motor functional tests would be more relevant if they involved mitotic spindle assays, rather than peroxisome or Golgi dispersion assays. It is not clear how the loads involved in peroxisome or Golgi dispersion are related to kinesin motor function in the spindle. What are the implications of low- vs high-load motors in the spindle? How do the authors envision that motor loads in spindles relate to loads borne by vesicle transport motors?

Minor points needed for clarity and reproducibility of the data:

Methods

Plasmids<br /> "MKLP1(1-711) lacks the insert present in KIF23 isoform 1" - the insert present in KIF23 isoform 1 but missing in MKLP1 (1-711) should be depicted/pointed out in Fig. S1 and information provided as to its predicted or actual structure.

"KIF20B contained the protein sequence conflict E713K and natural variations N716I and H749L "- the sites of these changes should be indicated in Fig. S1 and information provided as to their effects on predicted or actual structure.<br /> Protein purification: "MKLP1(1-711)-3xFLAG-Avi was cloned by stitching four oligonucleotide primer sequences together into a digested MKLP1(1-711)-Avitag plasmid" - please explain what this means: what do the four oligonucleotide primer sequences correspond to? if they are the 3xFLAG-Avi tags, why were four sequences stitched together instead of three?<br /> The figures showing the kymographs should include labeled X and Y axes, rather than scale bars.

The significance of the statement that "All motors displayed similar behaviors when tagged with Halo and Flag tags" is not clear, as the Halo and Flag tags were also C-terminal tags, like the 3xmCit tag.

The figures (Fig. 3-5) that contain grey-scale cell depictions would be more readily interpretable by others if they were labeled with the authors' classification of the dispersion phenotype.

Significance

This manuscript reports motility characteristics and load-bearing properties of three human kinesin-6 family proteins that function during late telophase/cytokinesis of mitosis. The authors report single molecule and multiple motor motility assays, and vesicle dispersion assays for the three motors. Because the kinesin motors are important for normal division, their motility characteristics are of interest to workers in the mitosis field. However, data presentation in this manuscript could be greatly improved, along with interpretations of functional differences based on kinesin-6 motility properties.

My expertise: motors, motor function in division, motility assays, microtubules

-

- Oct 2022

-

github.com github.com

-

<p>All heading tags are working well but the hierarchy in the webpage is missing which is making the page unstructured. This is somehow missleading the viewers as they will not get the difference between headings and links.So, the mixure of headings and links seems irrelevant here. Instead, the headings could be managed either side of the page and links towards the oposite side. This will be east for the people to scroll the page to get information easily. Most importantly, the align attrribute in h3 tag is a wrong use. </p>

Because there is no maximum width specified, paragraph elements that are very long like this one show up as very long on the user's browser. This is not very readable.

-

<span>Comox Valley Lifeline Society</span> <p>Span tag is not necessary to use here. Instead simple heading tag could work here</p>

When you use <span> tags here as an example, they do not render on the user's browser. Character entities must be used if you want to display reserved characters like < and >. See this for more information.

-

<!--<p align="justify" class="plain">The Comox Valley Lifeline Society offers a variety of medical alert services designed specifically for older adults that provide fast, 24/7 access to expert help in an emergency. These services range from the standard HomeSafe service to the fall detection capability of the HomeSafe with AutoAlert and the freedom of the new GoSafe mobile service. </p>--> <ol> <li>There is again wrong use of align attribute in the paragraph tag</li>

When you talk about how they use the align attribute wrong, they can't see the code you're talking about.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<a href=

probably keeps the tag together.

-

-

store.steampowered.com store.steampowered.com

-

a little flaw (Google translation can not find the translation of the word "瑕疵", so can only use the word "flaw" instead)

annotation meta: may need new tag: no exact translation in other language

-

-

steamcommunity.com steamcommunity.com

-

so this means that there are no documentation telling you that this is the way you have to do it anywhere so naturally a lot of devs do not know about this, unless they ask about it by luck or of curiousity.

annotation meta: may need new tag: how could they know / how would one find out?

-

-

github.com github.com

-

the css part is done very great and they have right space in between the codes , like we can easily see the each tag and what is used in it. i also saw new thing like we can use h1,h2 tags combine and edit it together

-

-

github.com github.com

-

.<p>

This has to be a close tag.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

i loved it how you write the code its very clean and easy to read and every tag is used appropriate.

-

</li> <li>Use the 60-30-10 rule to balance the three colours.</li>

You might want to consider consistency in formatting. In the first one the closing tag of list item is placed on a new line and in the next one it is placed right after the content.

-

-

benwerd.substack.com benwerd.substack.com

-

Given your talents, if you've not explored some of the experimental fiction side of things (like Mark Bernstein's hypertext fiction http://www.eastgate.com/catalog/Fiction.html, Robin Sloan's fish http://www.robinsloan.com/fish/ or Writing with the Machine https://www.robinsloan.com/notes/writing-with-the-machine/, or a variety of others https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=tag%3A%22experimental+fiction%22), perhaps it may be fun and allow you to use some of your technology based-background at the same time?

-

-

boffosocko.com boffosocko.com

-

One can’t help but notice the proliferation of specific method names for slightly different practices within the now growing space. These specific names for practices literally give both a name and power to the space and help to make it grow. Some of these names include: Zettelkasten itself as a name for Luhmann’s method; Smart Notes (Sönke Ahrens’ delineation of Luhmann’s method, Linking Your Thinking (aka LYT, Nick Milo’s method); Building a Second Brain (BaSB, Tiago Forte’s method); ANTInet (Scott P. Scheper’s analog branded version of Luhmann’s method); and even Pile of Index Cards (PoIC, Hawk Sugano’s productivity-based method from 2006). The naming tends to expand here as many of these examples have a commercial need to differentiate these practices to make them sellable to a larger audience. Should one really consider it a coincidence that Obsidian is so heavily used by those in Tiago Forte’s Building a Second Brain camp when Obsidian’s tag line on their home page boldly declares “A second brain, for you, forever.”? This naming craze even extends to a proliferation of names for note types within each system including fleeting notes, permanent notes, literature notes, atomic notes, evergreen notes, source notes, point notes, concept notes, claim notes, etc. Of course the power of naming begins to wane here as the over-proliferation of names causes semantic collisions and worries when these systems and their adherents talk about related ideas online in broader overlapping publics. One would presume that over time this list of names will settle down and roughly standardize around a much smaller (dare I say atomic?), possibly mutually exclusive set.

Another example of marketing serving badly for the concepts being easily studied and used. Positioning and differentiation backfires here. Lack of sources linking is a huge issue in a popular non-fiction.

-

-

-

XML is not limited to a specific set of tags, because a single tag set would not adapt to all documents or applications that may use XML.

Unlike HTML XML is more useful and flexible when adapting to other applications while HTML is restricted to only one set of tags

-

-

stackoverflow.com stackoverflow.com

-

The problem is that the caller may write yield instead of block.call. The code I have given is possible caller's code. Extended method definition in my library can be simplified to my code above. Client provides block passed to define_method (body of a method), so he/she can write there anything. Especially yield. I can write in documentation that yield simply does not work, but I am trying to avoid that, and make my library 100% compatible with Ruby (alow to use any language syntax, not only a subset).

An understandable concern/desire: compatibility

Added new tag for this: allowing full syntax to be used, not just subset

-

-

raku.org raku.org

-

Definable grammars for pattern matching and generalized string processing

annotation meta: may need new tag: "definable __"?

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Note: This rebuttal was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. Content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

We would like to thank the Reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions concerning our manuscript entitled " Drosophila pVALIUM10 TRiP RNAi lines cause undesired silencing of Gateway-based transgenes" (RC-2022-01629).

Please find below our responses to the Reviewers' questions and comments. We have revised the Manuscript following the Reviewers' suggestions. The changes in the Manuscript are indicated in blue.

Reviewer #1 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)): ____ This manuscript by Uhlirova and colleagues identified an unwanted off-target effect in the pVALIUM10 TRiP RNAi lines that are commonly used in the fly community. The pVALIUM10 lines use long double-stranded hairpins and are useful vectors for somatic gene knock-down, hence they are widely used.

Here the authors find that any pVALIUM10 TRiP RNAi line can create the silencing of any transgenes that were cloned with the commonly used Gateway system. this is caused by targeting attB1 and attB2 sequences, which are also present in other Drosophila stocks including the transgenic flyORF collection. Hence, this is an important and useful information for the fly community that should be published quickly. All experiments are well documented and well controlled. I only have a few minor comments.

-

I recommend to mention the number of 1800 pVALIUM10 lines in Bloomington in the abstract rather than 11% to make clear that this is an important number of lines. (1800 of 13,698 lines in Bloomiongton are 13 and not 11 per cent?)

We now include the absolute number of pVALIUM10 lines in the manuscript abstract. The percentages have been corrected. Furthermore, we updated/corrected the total number of RNAi lines available from various stock centers in the Discussion, L153-L156.

The status on 23.10.2022

VDRC - 23,411 in total (12,934 GD lines; 9,674 KK lines; 803 shRNA lines)

Bloomington - 13,410 TRiP lines based on pVALIUM vectors (13,674 in total, including 264 non-pVALIUM, and 48 non-fly genes targeting lines)

NIG - 12,365 in total (5,676 TRiP lines; 7,923 NIG RNAi lines)

The authors may consider to call the 'unspecific' silencing effect an 'off-target' effect compared to intended 'on-target'. Such a nomenclature would be more consensus.

We changed the wording in the manuscript as suggested by the reviewer.

Ideally, all the imaging results in Figure 2 and 3 would be quantified. The simple 'V10' label in the Figure 3L and 3M is not the most intuitive, at least it took me a while to figure out what the authors compare.

The labeling in the charts has been changed. We now provide quantifications for the data shown in Figure 2 and 3.

Does the silencing also affect attR sequences? These are present after cassette exchange in many transgenes, most of the time not in the mRNA though, so it might not be so relevant.

A 22 nucleotide stretch of the attB2 site indeed shows a 100% match to the attL2 site. See the example alignment below (availbale in word/PDF version of the Letter). While we did not assess this possibility experimentally, attL sites would likely be susceptible to the same undesirable off-target silencing effects if present in the nascent or mature transcript.

Reviewer #1 (Significance (Required)): This is an important and useful information for the fly community that should be published quickly.

Reviewer #2 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)): ____ Stankovic, Csordas, and Uhlirova show that a specific subset of the TRiP RNAi lines available, namely the pVALIUM10 subset, can cause a knockdown of certain co-expressed transgenes that contain attB1 and attB2 sites. The authors demonstrate that while pVALIUM20 or Vienna KK lines for BuGZ or myc RNAi do not affect RNase H1:GFP expression, pVALIUM10 RNAi lines against BuGZ or myc significantly decrease expression of the RNAseH1:GFP transgene. The authors propose that, due to how these RNAi lines were constructed, the siRNA products could be targeting to attB1 and attB2 sites in transgenes that were made using similar methodology. To support this idea, they ubiquitously express mCherry transgenes encoding mRNAs either containing or lacking attB sites. They find that the knockdown of mCherry seen with several different pVALIUM10 RNAi lines is observed with the reporter mRNA containing attB sites, but is suppressed when the attB sites are removed from mCherry mRNA. They also find that the pVALIUM10 RNAi lines reduce the expression of the FlyORF transgene SmD3:HA.

The paper is very clearly written and the data presented is convincing.

Minor suggestions:

1. Figure 3 L+M The labels for the ubi-mcherry and ubiΔattb-mcherry are switched in these graphs (i.e. ubiΔattb-mcherry should be the one with a higher intensity in the pouch compared to the notum).

Figure 3M the labels don't match the RNAi lines used in H-K.

We corrected the labelling in the charts.

Figure 2 and 3. For the images of the transgenes, it seems as if the BuGZ RNAi line has a more drastic effect on RNaseH1 than mCherry, and vice versa for the myc RNAi lines. Did the authors notice a pattern with the decreased expression. Do some of the RNAi lines have a more consistent/severe impact, or might different transgenes be impacted to different extents?

Throughout the study and multiple experimental trials, we did not observe that the BuGZRNAi and mycRNAi silencing efficiency would depend on whether the monitored reporter was RNase H1::GFP or mCherry. What has been reproducible is the differential impact of the three tested mycRNAi lines on ubi-RNaseH1::GFP transgene. While pVALIUM10-based mycRNAi[TRiP.JF01761] reduces RNaseH1::GFP signal Valium20 mycRNAi[TRiP.HMS01538] enhances it and GD mycRNAi[GD2948] has no effect, although the number of replicates for the latter is lower compared to the other tested lines. Why Valium20 mycRNAi[TRiP.HMS01538] increases RNaseH1::GFP signal remains unclear for now.

We would like to refrain from directly quantitatively comparing the effects of phenotypically different RNAi lines on differently tagged mRNAs/proteins. As the RNAseH1::GFP fusion protein is nuclear while the mCherry is cytoplasmic, their distinct subcellular localization and/or turnover rate may give a different overall impression on the change in fluorescence intensity (Boisvert et al, 2012; Mathieson et al, 2018). Another confounding factor is the described roles of Drosophila Myc in regulating transcription, translation, and cell growth (Gallant, 2007).

Line 150 unnecessary comma after Both Line 131 knockdown should be knocked down Line 133 should be "using an additional" Figure legend 1 wing disc should be at least written out when the abbreviation (WD) is first used.

We thank the reviewer for pointing these out, the relevant corrections were performed.

Reviewer #2 (Significance (Required)):

Overall, this manuscript is an informative reminder that RNAi lines can have weaknesses that have not yet been considered, and we appreciate the authors work to inform the fly community about this specific issue. These insights are crucial for fly labs to consider when planning experiments that will use the pVALIUM10 RNAi lines in combination with other transgenesis modalities. The manuscript also provides a cautionary note for the usage of similar resources in other model organisms.

Reviewer #3 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)): Summary: In their manuscript "Drosophila pVALIUM10 TRiP RNAi lines cause undesired silencing of Gateway-base transgenes", Stankovic et al. describe off-target silencing of transgenes expressed from Gateway systems when expressed in transgenic RNAi drosophila lines from the VALIUM10 collection. Using fluorescence microscopy and immunostaining, the authors show that this unintended silencing is specific to VALIUM20 lines and is not observed with VALIUM20, KK or GD lines that also allow gene-specific RNAi silencing. This pleiotropic silencing effect was observed in 10 different VALIUM20 lines and affected Gateway-based transgene expressed from an ubiquitous promoter (poly-ubiquitin, ubi) or from Gal4/UAS systems. Finally, the authors identify the molecular basis of VALIUM20 pleiotropic silencing on Gateway transgenes as being due to the presence of short sequences used for PhiC31-based recombination in the Gateway and the VALIUM systems, and could lead to the production of siRNAs against PhiC31 recombination sites in VALIUM10 lines. Using Gateway transgenes lacking the recombination sites (attB1 and attB2), the authors could abrogate silencing of the transgene in VALIUM10 lines, confirming the recombination as shared targets between the Gateway and the VALIUM systems.

Major comments: - The study is well designed and the key conclusions are convincing. - However, the authors provide only fluorescence microscopy data to show decreased transgene expression. To confirm pleiotropic RNAi effect on Gateway transgenes in VALIUM10, the authors should assess silencing with another technique. For instance, expression levels of proteins from Gateway transgenes could be measured by Western blot (e.g.: by assessing protein levels of GFP or other tags present in the Gateway transgenes).

In the manuscript, we present microscopy data as this is the typical use case for fluorescent reporters. The strength of the microscopy, in contrast to Western Blot or RT-qPCR approach, is that it allows us to directly compare the impact of RNAi silencing on cells that express the dsRNA transgene (cell-autonomous) to surrounding neighbor cells. The fluorescent imaging of WDs where all cells express the reporter construct, but only a subset of cells trigger RNAi-mediated silencing, provides spatial resolution and means for normalization while minimizing artifacts that can arise during tissue processing for WB and RT-qPCR. We provide data on GFP and HA-tagged transgenes, respectively, and untagged mCherry expressed from Gateway vectors under ubiquitin or UAS regulatory sequences with the explicit reason to show that the silencing effect is independent of the type of the protein tag or the expression regulator sequence.

In addition, the claim on line 141,"These results strongly indicate that the dsRNA hairpin produced from pVALIUM10 RNAi vectors generates attB1- and attB2-siRNAs" , should be modified. The authors only present fluorescence microscopy data to show decreased transgene expression and do not actually provide data on siRNA expression in the pVALUM20 lines. Therefore, with the current data, the authors should only say that their results suggest that the dsRNA hairpin produced from pVALIUM10 RNAi vectors generates attB1- and attB2-siRNAs.

In order to substantiate their claim about pleiotropic RNAi effects from VALIUM lines on Gateway transgenes due to the production of attB1- and attB2 -siRNAs, the authors should perform an experiment to show attB1- and attB2 -siRNAs production in VALIUM10 lines and not in VALIUM20, KK or GD lines. Deep-sequencing analysis of siRNA (i.e.: miRNA-seq) from tissue expressing the corresponding RNAi transgenes would be an excellent approach to assess siRNA production in multiple samples at once. Alternatively, the authors could search published miRNA-seq datasets from VALIUM10 and other RNAi lines to assess the presence of attB1- and attB2 -siRNAs only in VALIUM10 lines. This would be free and require only a few days of data mining and analysis, if such datasets exist already. Another cheaper and faster approach (if lacking easy access to sequencing platform or bioinformatics capability) would be to perform small RNA northern blots analysis from fly tissues expressing VALIUM10 vs VALIUM20 (or KK or GD lines) and should take only a few days to do as described in doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.67.

If such experiments or analyses cannot be performed, then the authors can only conclude that their data suggest that the unintended silencing of Gateway transgenes in VALIUM10 is likely due to the production attB1- and attB2 -siRNAs production.

We thank the reviewer for the valuable suggestions on experimental approcahes to identify the exact interfering RNAs produced by the VALIUM10-based RNAi constructs, which can be useful for controlling the specificity of knockdown of transgenes in studies using the resources mentioned in this report.

We believe the fluorescence micrographs and quantifications demonstrate the off-target silencing effects of pVALIUM10-based RNAi lines on transgenic reporters generated using the Gateway LR cloning approach. Furthermore, we provide genetic evidence that removing the attB1 and attB2 sites from the reporter construct, which is otherwise identical to the original transgene (same promoter, same position of insertion, same genetic background), is sufficient to abolish the off-target effect. We would argue that the functional genetic experiments we performed with the original and mutated reporters represent the strongest possible evidence to confirm that silencing is taking effect via the attB sites.

As we do not attempt to detect siRNA complementary to attB1/attB2 sites directly, we have changed the statements in question as per the recommendation of the reviewer.

- The current data and methods are adequately detailed and presented, and the statistical analysis adequate.

Minor comments:

- The current manuscript does not have specific experimental issues.

- Prior studies are referenced appropriately

- Overall the text and figures are clear and accurate except for the following issues with Figure 3 and its legends On lines 396, 397, 399 and 403, the authors refer to "wild-type" ubi-mCherry. This transgene directs the ubiquitous expression of an heterologous reporter gene and thus can not as "wild type". It could instead be referred to as the "original" or "unmodified" transgene.

We removed "wild-type" from the text.

Fig.3 L: the x-axis labels are wrong. Decrease in the mCherry intensity ratio is observed with the ubi-mCherry construct and not in the ubi∆attB-mCherry, where the attB sequences thought to be targeted by the pVALIUM10 have been deleted.

More space should be added between the first row of images (B-G), the second (H-L) and also the third (M-P) to avoid confusion between the labeling of the figures. Finally, to help contextualize their findings and gauging the extent of the risk of using VALIUM10 lines in RNAi screen where a Gateway transgene is involved, the authors could provide information on the overlap between the VALIUM10 collection and VALIUM20, GD and KK collections. Knowing how many genes are uniquely targeted by VALIUM10, could be helpful.

We corrected the Figure panels according Reviewer 1 and 3’s observation.

Of the TRiP pVALIUM-based RNAi stocks currently available in BDSC, 686 genes are targeted exclusively by pVALIUM10 RNAi lines. Considering KK, GD and shRNA transgenic lines from VDRC and NIG RNAi collection, 17 genes remain unique targets for pVALIUM10 lines. The graphical overview of the availbale lines is availbale in the word/PDF file of the Response to Reviewers Letter.

Reviewer #3 (Significance (Required)):

- The manuscript "Drosophila pVALIUM10 TRiP RNAi lines cause undesired silencing of Gateway-base transgenes" by Stankovic et al. is a technical study that sheds light on potential limitations of using common RNAi drosophila lines, namely the VALIUM10 collection.

- The study provides information about very specific genetic screens conditions in Drosophila, that are likely to be rare. A rapid Pubmed search with the following terms: "drosophila TRiP screen" returns only 11 citations, while a similar search with "drosophila CRISPR screen" returns 99 citations. This suggests that in vivo RNAi screen in Drosophila using TRiP RNAi collections might not be as common or powerful as CRISPR-based screens.

- The reported findings might be of interest mostly to a small group of scientists working with Drosophila melanogaster that specifically rely on VALIUM10 lines to perform in vivo RNAi screen in combination with Gateway transgene expression. This very specific combination of parameters is rare, since other RNAi fly stock collections exist (e.g.: VALIUM20, 21, KK, GD...). Furthermore, the advent of CRISPR tools that allows tissue-specific gene knock-out has led to the rapid expansion of CRISPR fly stock collections (https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.53865). Regardless of the limited scope of the study, this kind information is still valuable, albeit to a very limited audience.

- My relevant fields of expertise for this study are : insect RNAi, RNAi of RNAi screens and drosophila genetics.

We would like to raise some points concerning the above comments.

While TRiP-screen may not be an often-used keyword combination, the use of the TRiP lines is, in fact, ubiquitous in the Drosophila community. The tissue-specific RNA interference is still commonly utilized as a rapid, first-generation screening method that can be performed in a tissue-specific manner, representing one of the key advantages of the Drosophila model. To illustrate, since the submission of our manuscript a new study published by Rylee and co-workers investigated Drosophila pseudopupil formation by screening 3971 TRiP RNAi lines (Rylee et al, 2022). In contrast, genetic screens relying on mutant alleles usually require at least one additional cross, effectively doubling the time of the experiment. In addition, tissue-specific or temporarily restricted knockdown is sometimes required in screens, as full-body loss of function is often lethal or has developmental phenotypes incompatible with assessing gene function later in life.

The use of tissue-specifically driven Cas9 with integrated gRNA-expressing vectors is indeed becoming more common. However, this technique, much like RNA interference, is not without flaws. First, this produces knockout instead of knockdown, which means it has to be induced early in order for the resulting mutation to take effect. Otherwise, the remaining mRNA/protein may prevent the development of a phenotype. Second, the Cas9 must be titrated as high Cas9 levels have adverse phenotypes (Huynh et al, 2018; Meltzer et al, 2019; Poe et al, 2019; Port et al, 2014). Third, in our personal experience, as well as literature reports (Mehravar et al, 2019; Port & Boutros, 2022), indicate that the resulting phenotype can produce mosaics in the tissue.

Although the combination of Gateway-based reporters with TRiP-RNAi lines may seem like a fringe case, there are popular reporters that could be screening targets. Potentially the most well-known is the live cell cycle indicator fly-FUCCI system (Zielke et al, 2014), which allows the analysis of the cell cycle in real-time thanks to the expression of two fluorescently tagged degrons. As FUCCI transgenes were constructed with Gateway recombination, they represent targets of the pVALIUM10 TRiP lines. We now include the fly-FUCCI system as an example in addition to 3xHA-tagged FlyORF collection in the Discussion.

REFERENCES

Boisvert FM, Ahmad Y, Gierlinski M, Charriere F, Lamont D, Scott M, Barton G, Lamond AI (2012) A quantitative spatial proteomics analysis of proteome turnover in human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: M111 011429

Gallant P (2007) Control of transcription by Pontin and Reptin. Trends Cell Biol 17: 187-192

Huynh N, Zeng J, Liu W, King-Jones K (2018) A Drosophila CRISPR/Cas9 Toolkit for Conditionally Manipulating Gene Expression in the Prothoracic Gland as a Test Case for Polytene Tissues. G3 (Bethesda) 8: 3593-3605

Mathieson T, Franken H, Kosinski J, Kurzawa N, Zinn N, Sweetman G, Poeckel D, Ratnu VS, Schramm M, Becher I et al (2018) Systematic analysis of protein turnover in primary cells. Nature Communications 9: 689

Mehravar M, Shirazi A, Nazari M, Banan M (2019) Mosaicism in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Developmental Biology 445: 156-162

Meltzer H, Marom E, Alyagor I, Mayseless O, Berkun V, Segal-Gilboa N, Unger T, Luginbuhl D, Schuldiner O (2019) Tissue-specific (ts)CRISPR as an efficient strategy for in vivo screening in Drosophila. Nature Communications 10: 2113

Poe AR, Wang B, Sapar ML, Ji H, Li K, Onabajo T, Fazliyeva R, Gibbs M, Qiu Y, Hu Y et al (2019) Robust CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Tissue-Specific Mutagenesis Reveals Gene Redundancy and Perdurance in Drosophila. Genetics 211: 459-472

Port F, Boutros M (2022) Tissue-Specific CRISPR-Cas9 Screening in Drosophila. In: Drosophila: Methods and Protocols, Dahmann C. (ed.) pp. 157-176. Springer US: New York, NY

Port F, Chen HM, Lee T, Bullock SL (2014) Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E2967-2976

Rylee J, Mahato S, Aldrich J, Bergh E, Sizemore B, Feder LE, Grega S, Helms K, Maar M, Britt SG et al (2022) A TRiP RNAi screen to identify molecules necessary for Drosophila photoreceptor differentiation. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics: jkac257

Zielke N, Korzelius J, van Straaten M, Bender K, Schuhknecht GFP, Dutta D, Xiang J, Edgar BA (2014) Fly-FUCCI: A versatile tool for studying cell proliferation in complex tissues. Cell Rep 7: 588-598

-

-

-

hypothes.is hypothes.is

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

roadturtlegames.com roadturtlegames.com

-

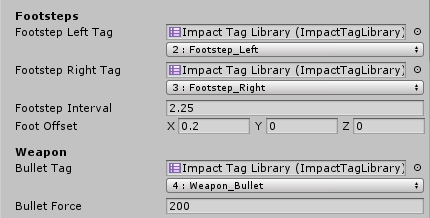

Impact Materials define what interactions will occur when an object interacts with the tags defined in the Impact Tag Library

-- the Impact Tag Library is where we define the list of tags for our materials.

i.e.: Plastic, Glass, Concrete...etc

-

-

roadturtlegames.com roadturtlegames.com

-

The first field is an Impact Tag Library which is used to display a user-friendly dropdown for the tag or tag mask. The second field represents the actual value of the tag or tag Mask

-

Just remember that under the hood tags are represented only by integers, so using multiple tag libraries with different tag names does not mean you can have more than 32 tags.

Tags

-

-

mcrcalicante.wordpress.com mcrcalicante.wordpress.com

-

Actualmente, el nacionalismo es más una reivindicación de autonomía fiscal y autogobierno que deseo real de un estado independiente

DESPUES DE LA GUERRA

-

surgen numerosos grupos denominados Movimiento de Liberación Naciona

DURANTE LA GUERRA

-

-

github.com github.com

-

href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Roboto&display=swap" rel="stylesheet"> <!-- google font--> <link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Noto+Sans&display=swap" rel="stylesheet">

Added 3 different google fonts in the head section by the tag LINK

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<h2>Meet the Team</h2>

i think you have to put this in h1 tag and make it more bold

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This paper has many strengths that support its conclusions. Specifically, the use of natively expressed Piezo1 engineered to carry the HA tag allowed the authors to explore the distribution of the protein from primary cells isolated from a mouse at native expression levels. Thus, over-expression effects could be avoided. The super-resolution imaging is nicely controlled and convicting in its analysis of the distribution of the channel in 3D. The supporting EM data also supports the findings from fluorescence. Likewise, the theory is convincing in proving a mechanistic reason why the channel distributes into this region of the cell. While the data are quite nice and well analyzed, the paper is lacking in an exploration of what function this distribution of the channel would provide to the cell. Likewise, if this distribution was disturbed, would the red blood cell's behavior change? For example, would calcium signals in response to an osmotic challenge or squeezing change if the channel was not concentrated in the dimple? As it stands now, the paper presents a structural view of the distribution of piezo1 in a primary cell plasma membrane but lacks direct experimental evidence for the mechanism of this concentration or mechanistic insight into the effects of this spatial distribution on red blood cell physiology.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<p>Located in the heart of the Comox Valley, Hairpins Boutique Salon offers a high-end experience with competitive prices, top of the line products and a warm, welcoming atmosphere.</p>

The individual element tags can be formatted as

opening tag

contentclosing tag

for better readability.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

</a >

This closing tag can be together for better readability.

-

/>

Closing tag not required. Everything else seems perfect.

-

/>

closing tag not required for img.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<address> <b>Hairpins Boutique Salon </b> <br/> #4 - 224 6th Street<br/> Courtenay, BC V9N 1M1<br/> </address>

Had no idea there was an address tag. Good use of proper semantic labelling.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

headline

Alt tag should contain information describing image

-

Live Breaking UK

Having all of these as H4 will not allow individual styling. Try enclosing each in a span or button tag then you can add background colour to each.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

rc="images/rum2.jfif

make sure to add alt tag

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<br />

The <br /> tag showed warning for me when I tried to validate my code. So I used <br>.. Everything else looks great.

-

-

-

EAD makes use of a tag structure that identifies the components of a document. Each component or part is identified, and noted through the encoding. Because EAD is an application of XML, EAD utilizes the concepts of tags, elements, and attributes for encoding text.

From my understanding, EAD is used only for archival files, and uses the components mentioned before.

-

-

cdrh.unl.edu cdrh.unl.edu

-

What is a Tag?

Tags must be correctly spelled and in the right position for them to work. A combination of tags cannot be used. This means that beginning tags cannot be used with empty tags or closing tags.

-

-

gamefound.com gamefound.com

-

First and foremost, we need to acknowledge that even though the funding goal has been met–it does not meet the realistic costs of the project. Bluntly speaking, we did not have the confidence to showcase the real goal of ~1.5 million euros (which would be around 10k backers) in a crowdfunding world where “Funded in XY minutes!” is a regular highlight.

new tag: pressure to understate the real cost/estimate

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Memorization is not about a language, rather about a feeling you have about information. In other words, how deep it resonates with your life. In this sense, I was also exploring the idea that having an Antinet Zettelkasten is almost like having a "diary", not for your personal feelings or emotions, rather for exploring the way in which your entire mind and heart work together over the years in which we discover the world. For me, exploring subjects and studying is an internal discovery.

in reply to los2pollos<br /> https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/y5un81/comment/it4jy3c/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

You're not the only one to think of a card index as diary. Roland Barthes practiced this as well. His biographer Tiphaine Samoyault came to call it his fichierjournal.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

<br>Contact us today to book an appointment!<br> <a href="contact.html">Contact Us</a> </main> <footer> Content taken from <a style="color: green" href="https://www.hairpins.ca/" >https://www.hairpins.ca</a >. Used for educational purposes only. </footer> <!--an inline style rule in anchor tag above--> </body>

nice work

-

-

minnstate.pressbooks.pub minnstate.pressbooks.pub

-

In the second case, checking “Connection” in my Index would lead me to this card. I might then compare this thought to others that use the same keyword, to see how it supports or modifies the idea of connection.

The reliance upon tag-like keywords in physical note-taking of this type seems to be a limitation compared to digital systems that allow full text search. That said, the benefits of full text search might be somewhat overblown, as found search terms say nothing of the context and would need either tags or a quick read of the text to provide that context.

-

-

github.com github.com

-