Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Reviewer #1

Summary:

Miyamoto et al. report that importin α1 is highly enriched in a subfraction of micronuclei (about 40%), which exhibit defective nuclear envelopes and compromised accessibility of factors essential for the damage response associated with homologous recombination DNA repair. The authors suggest that the unequal localization and abnormal distribution of importin α1 within these micronuclei contribute to the genomic instability observed in cancer.

Major comments:

1.) It is crucial to quantitatively assess the localization of importin α1 in micronuclei (MN) across non-transformed MCM10A cells compared to transformed cell lines (MC7, HeLa, and MDA-MB-231). This analysis would help determine whether the localization of importin α1 in MN correlates with genomic stability in human cancer cells

We appreciate the reviewer's thoughtful suggestion to compare non-transformed and transformed cell lines to evaluate importin α1 localization in MN. Given that HeLa cells are derived from cervical cancer rather than the mammary epithelium, we considered it inappropriate to directly compare them with non-transformed mammary epithelial MCF10A cells. Therefore, HeLa cells were analyzed separately to assess the effects of reversine treatment on importin α1 localization. The results indicated no significant difference between the treated and untreated HeLa cells. (Supplemental Fig. S2F in the revised manuscript). Regarding the comparison between MCF10A and the two cancer cell lines, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231, the proportion of importin α1-positive MN did not significantly differ across the cell lines, regardless of reversine treatment (Supplemental Fig. S3B, Untreated: p = 0.9850 and 0.5533; Reversine: p = 0.2218 and 0.9392). These results suggest that there is no clear difference in the localization of importin α1 in MN between the transformed and non-transformed cell lines tested. However, we acknowledge that this does not exclude the possibility that importin α1 localization to MN is linked to genomic instability under specific conditions.

2.) While the authors provide some evidence indicating partial disruption of nuclear envelopes in MN (Figures 3 and S4), it is noteworthy that this phenomenon also occurs in importin α1-negative MN. Furthermore, according to the figure legends, the data presented in both figures stem from a single experiment. Current literature suggests that compromised nuclear envelope integrity is one of the major contributors to genomic instability, mediated through mechanisms such as chromothripsis and cGAS-STING-mediated inflammation arising from MN. Therefore, a more comprehensive quantification of nuclear envelope integrity-ideally comparing non-transformed MCM10A cells with transformed cell lines (MC7, HeLa, and MDA-MB-231)-is necessary to substantiate the connection between aberrant importin α1 behavior in MN and chromothripsis processes, as well as regulation of the cGAS-STING pathway linked to genomic instability in cancer cells.

We thank the reviewer for the constructive suggestion to quantify nuclear envelope integrity more comprehensively. In response, we compared laminB1 localization at the MN membrane between importin α1-positive and -negative MN in MCF10A, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa cells, and included these results in the revised manuscript (Fig. 4C). For each cell, the laminB1 intensity in the MN was normalized to that of the primary nucleus (PN). This analysis showed that laminB1 intensity was significantly lower in importin α1-positive MN across all cell lines, including non-transformed MCF10A cells. These findings support a close association between aberrant importin α1 accumulation and compromised nuclear envelope integrity, a key factor potentially linking MN to chromothripsis and cGAS-STING-mediated genomic instability.

3.) The schematic illustration presented in Figure 8 does not adequately summarize all findings from this study nor does it clarify how the localization of importin α1 within MN might hypothetically influence genome stability. Although it is reasonable to propose that "importin α can serve as a molecular marker for characterizing the dynamics of MN" (Line 344), the authors assert (Line 325) that their findings, along with others, have "potential implications for the induction of chromothripsis processes and regulation of the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer cells." However, they fail to provide a clear or even hypothetical explanation regarding how their findings contribute to these molecular events. To address this gap, it would be essential for them to contextualize their results within existing literature that explores and links structural integrity deficits or aberrant DNA replication/damage responses in MN with chromothripsis and inflammation (e.g., PMID: 32601372; PMID: 32494070; PMID: 27918550; PMID: 28738408; PMID: 28759889).

We agree that the previous schematic illustration (former Fig. 8) did not adequately summarize our findings and may have overstated our conclusions. Accordingly, we have removed this figure from the revised manuscript.

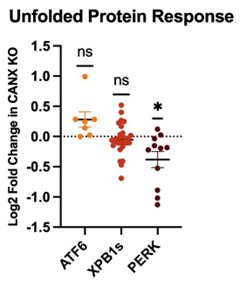

To address the reviewer's concern, we performed additional analyses and included the results in the new Figure 8. These data show that, in addition to RAD51, both RPA2 and cGAS display mutually exclusive localization with importin α1 in MN. RPA2, a single-stranded DNA-binding protein, stabilizes damaged DNA and enables RAD51 filament assembly during homologous recombination repair. Previous studies have demonstrated that RPA2 accumulates in ruptured MN in a CHMP4B-dependent manner (PMID: 32601372). Likewise, cGAS is a cytosolic DNA sensor that localizes to ruptured MN and activates innate immune signaling through the cGAS-STING pathway, as widely reported (PMID: 28738408; 28759889; see also PMID: 32494070; 27918550).

Our findings suggest an alternative scenario: even when nuclear envelope rupture occurs, importin α1-positive MN may remain inaccessible to DNA repair and sensing factors such as RPA2 and cGAS. This supports the view that importin α1 defines a distinct MN subset, separate from those characterized by the canonical DNA damage response or innate immune signaling factors. Furthermore, our overexpression experiments with EGFP-importin α1 (Fig. 7G, 7H) raises the possibility that importin α1 enrichment may impede the recruitment of DNA-binding proteins.

Taken together, these results support the conclusion that importin α1 marks a unique MN state and provides a molecular framework for distinguishing between different MN environments. At the reviewer's suggestion, we have cited all the recommended references (PMID: 32601372, 32494070, 27918550, 28738408, and 28759889) in the revised manuscript to better contextualize our findings. We are grateful for the reviewer's thoughtful suggestions and literature recommendations, which helped us clarify the implications of our findings within the broader context of chromothripsis and cGAS-STING-mediated genomic instability.

4.) Fig. 4D does not support the idea that importin α1 is euchromatin enriched: H3K9me3, H3K4me3 and H3K37me3 seem to be all deeply blue.

We sincerely thank the reviewer for pointing out the important limitations of the original version of Fig. 4D, as also raised in minor comment #5. As the reviewer correctly noted, this figure was intended to demonstrate that importin-α1 preferentially localizes to euchromatin regions (H3K4me3 and H3K36me3) rather than heterochromatin (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3). However, we acknowledge that in the original figure, the predominantly blue tone of the heatmap made this interpretation unclear and that the Spearman's correlation coefficient for H3K36me3 was missing. In response, we have substantially revised the figure (now shown as Fig. 5E in the revised manuscript). Specifically, we improved the color scale for better visual distinction, added the missing Spearman's coefficients for H3K36me3, and strengthened the analysis by incorporating ChIP-seq data obtained with two independent antibodies against importin α1 (Ab1 and Ab2). We believe that these revisions provide a clear and more accurate representation of euchromatin enrichment of importin-α1, as originally intended.

Indeed, the data presented by the authors do not adequately support a direct link between the presence of importin α1 in MN and genomic instability in human cancer cells. While the experimental correlations provided may not substantiate this connection definitively, they do lay a foundation for a grounded hypothesis and suggest the need for further research to explore this topic in greater depth. Additionally, it is worth noting that the evidence contributes to the growing list of nuclear proteins exhibiting abnormal behavior in micronuclei (MN). This highlights the significance of studying such proteins to understand their roles in genomic stability and cancer progression.

Following the reviewer's suggestion, we carefully revised the manuscript to ensure that our statements are consistent with the scope of the data and do not overstate our conclusions. As part of this effort, we removed the schematic illustration (former Fig. 8), which might have overstated our findings, and refined the relevant text to prevent overinterpretation.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report the specific accumulation of importin α in MN. Our results suggest a previously unrecognized function of importin α beyond its canonical transport role and add to the growing list of nuclear proteins that exhibit abnormal behavior in MN. We hope that these findings will provide a conceptual and experimental basis for future studies aimed at clarifying the biological significance of MN heterogeneity and quality control in cancer biology.

Additional experiments are necessary to quantitatively assess the localization of importin α1 in micronuclei (MN) across non-transformed MCM10A cells and transformed cell lines (MC7, HeLa, MDA-MB-231). This analysis would help determine whether the localization of importin α1 in MN correlates with genomic stability in human cancer cells.

As part of our response to Major Comment 1, we conducted additional experiments to quantitatively compare importin α1 localization in MN between non-transformed MCF10A cells, breast cancer cell lines (MCF7 and MDA-MB-231), and HeLa cells. These results have been included in the revised manuscript (Supplemental Fig. S2F and Fig. S3B). The analyses showed no significant differences in the proportion of importin α1-positive MN among these cell lines, consistent with the reviewer's request for a more comprehensive evaluation.

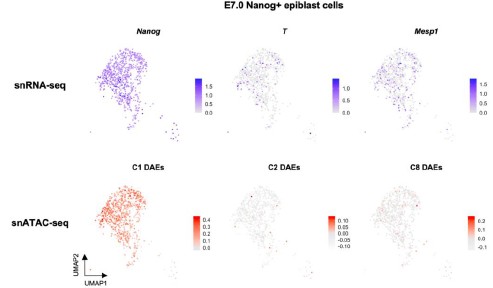

The authors claim that importin α1 preferentially localizes to euchromatic areas rather than heterochromatic regions within MN. While this assertion is supported by the immunofluorescence (IF) images presented in Figures 4A/B and S5A/B, it remains less clear for Figure S5C/B. To strengthen this claim, providing averages of IF distributions from multiple cells across independent experiments would be beneficial to draw more robust conclusions.

We have quantified the co-localization of importin α1 with the euchromatin marker H3K4me3 and the heterochromatin marker H3K9me3 in micronuclei (MN) across four human cell lines (MCF10A, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa). The results of this statistical analysis are included in the revised manuscript in Fig. 5C. These data provide quantitative evidence from independent experiments showing that importin α1 preferentially localizes to euchromatic regions within the MN, thereby supporting our initial observation.

Furthermore, ChIP-seq data are presented to support the idea that importin α1 preferentially distributes over euchromatin areas in MN. However, as described, the epigenetic chromatin status indicated by these ChIP-seq experiments reflects that of the principal nucleus (PN), not specifically the status within MN in MCF7 cells. Given that MN represent only a small fraction of the cell population under normal culture conditions-likely less than 5% for HeLa cells as shown in Figure S2D-the relevance of this data is limited. Additionally, according to data presented in Figure 1B, importin α1 does not localize or distribute within the PN as it does in MN in MCF7 cells. Therefore, further experiments should be conducted to substantiate that importin α1 preferentially targets euchromatin areas within MN and to compare this distribution with that observed in the principal nucleus. Such studies could reveal potential abnormalities regarding the correlation between epigenetic chromatin status and importin α distribution in MN.

As noted, these experiments were performed on whole-cell populations of MCF7 cells and therefore reflect the overall chromatin landscape, not specifically that of the MN. We fully acknowledge that MN constitute only a small fraction of the cell population under standard culture conditions (Supplemental Fig. S2D), and thus, the relevance of ChIP-seq data to MN must be interpreted with caution.

Nevertheless, our intention in presenting these data was to illustrate that importin α1 preferentially associates with euchromatin regions marked by H3K4me3. To examine this more directly, we analyzed importin α1 localization in MN using immunofluorescence with histone modification markers across multiple cell lines. These analyses, together with the quantitative results now included in the revised manuscript (Fig. 5C), confirming that importin α1 preferentially localizes to euchromatic regions within MN.

Taken together, although the ChIP-seq data were derived from whole-cell populations, the combined results from IF imaging and quantitative analysis support our interpretation that importin α1 retains its euchromatin-associating property within MN. We hope that these additional data will address the reviewer's concerns.

To support the hypothesis that importin α1 inhibits RAD51 accessibility within MN, Figures 7D and E should be supplemented with thorough quantification and statistical analysis based on at least three independent experiments. This additional data would enhance confidence in their findings regarding RAD51 accessibility inhibition by importin α1.

Following the reviewer's suggestion, we have added a new graph (Fig. 7F) in the revised manuscript. This figure presents the quantified frequency of RAD51-positive MN among importin α1-negative and importin α1-positive MN, analyzed across six microscopy fields (n = 6) from three independent experiments.

To improve clarity and consistency, we reorganized the panels: representative RAD51 images are now shown in Fig. 7B, and the Cell #1 (low RAD51) vs. Cell #2 (high RAD51) classification with etoposide responsiveness is summarized in Fig. 7C. As illustrated in Figs. 7D and 7E, importin α1 and RAD51 exhibit mutually exclusive localization in MN. Fig. 7F provides a unified statistical summary at the population level.

The results showed that the proportion of RAD51-positive MN was significantly lower among importin α1-positive MN than among importin α1-negative MN, providing robust quantitative support for the proposed mutual exclusivity between importin α1 localization and RAD51 accessibility in MN.

We are grateful to the reviewer for this constructive suggestion, which helped us clarify and better support the central message of our study.

The additional experiments proposed are controls and direct comparisons using the same techniques and experimental designs used by the authors, so it is reasonable that the authors can carry them out within a realistic timeframe.

We appreciate the reviewer's thoughtful consideration of the feasibility of the additional experiments.

Given the importance of reproducibility and the need to evaluate results based on imaging and quantitation, I strongly recommend that the authors include a detailed description of the optical microscopy procedures utilized in their study. This should encompass imaging conditions, acquisition settings, and the specific equipment used. Providing this information will enhance transparency and facilitate reproducibility. For reference, some valuable guidance on essential parameters for reproducibility can be found in Heddleston et al. (2021) (doi:10.1242/jcs.254144). Incorporating these details will not only strengthen the manuscript but also support other researchers in reproducing the findings accurately.

Following the reviewer's suggestion, we have substantially revised the Materials and Methods sections in the main and supplemental manuscripts to provide detailed descriptions of the optical microscopy procedures, including the specifications of the imaging equipment, acquisition settings, and image processing parameters. These revisions follow the best practices recommended by Heddleston et al. (2021, J. Cell Sci., doi:10.1242/jcs.254144).

We have also expanded the description of our quantitative image analysis using ImageJ, providing details on the parameters for MN identification and the measurement of colocalization rates between importin α and histone modifications. These additions ensured reproducibility and clarity.

We believe that these modifications will enhance the reproducibility of our results and increase the value of our study for the research community. We sincerely appreciate the reviewer's helpful suggestions.

Many of the plots and values in the manuscript lack appropriate statistical analysis, including p-values, which are not detailed in the figures or their legends. Furthermore, the Statistical Analysis section does not provide adequate information regarding the specific statistical tests employed or the criteria used to determine which analyses were applied in each case. To enhance the rigor and clarity of the study, it is essential that these issues be addressed prior to publication. A comprehensive presentation of statistical analysis will improve the reliability of the findings and allow readers to better understand the significance of the results. I recommend that the authors revise this section to include detailed explanations of all statistical methods used, along with corresponding p-values for all relevant comparisons.

We sincerely appreciate the reviewer's constructive comments highlighting the importance of transparent and rigorous statistical analyses. In response, we have carefully revised all figure panels, figure legends, and the Materials and Methods (Statistical Analysis) section in both the main and the supplementary manuscripts.

In the revised figure legends, we now provide the number of independent experiments and sample sizes (n), statistical tests applied (e.g., unpaired or paired two-tailed t-test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons), data presentation format (mean {plus minus} SD), and corresponding p-values or significance indicators (*, **, ***). The Statistical Analysis section was also expanded to explain the rationale for selecting each statistical test, the criteria for significance, and the reporting of the replicates. These revisions ensure clarity, reproducibility, and transparency throughout the manuscript, directly addressing the reviewers' concerns. We are grateful for this valuable suggestion, which has significantly improved the rigor of our study.

Minor comments:

The authors claim that importin α1 exhibits remarkably low mobility in the micronuclei (MN) compared to its mobility in the principal nucleus (PN), as illustrated in Figure 1. However, based on the experimental design, this conclusion may not be appropriate. In the current setup, the FRAP experiment conducted in the PN measures the mobility of importin α1 molecules within the cell nucleus, where the influence of nuclear transport is likely negligible. Conversely, in the MN experiments shown, all molecules of importin α1 are bleached within a given MN. Consequently, what is being measured here primarily reflects the effects of nuclear transport rather than intrinsic molecular mobility. To accurately compare kinetics of nuclear transport, it would be essential to completely bleach the entire PN. If measuring molecular mobility between MN and PN is desired, only a small fraction of either MN or PN area/volume should be bleached during FRAP analysis. Additionally, it would be beneficial to include measurements of mobility for other canonical nuclear transport factors (e.g., RAN, CAS, RCC1) for comparative purposes. This broader context would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of importin α1 behavior relative to other factors involved in nuclear transport. Finally, utilizing cells that exhibit importin α1 signals in both PN and MN could further strengthen comparisons and provide more robust conclusions regarding its mobility dynamics.

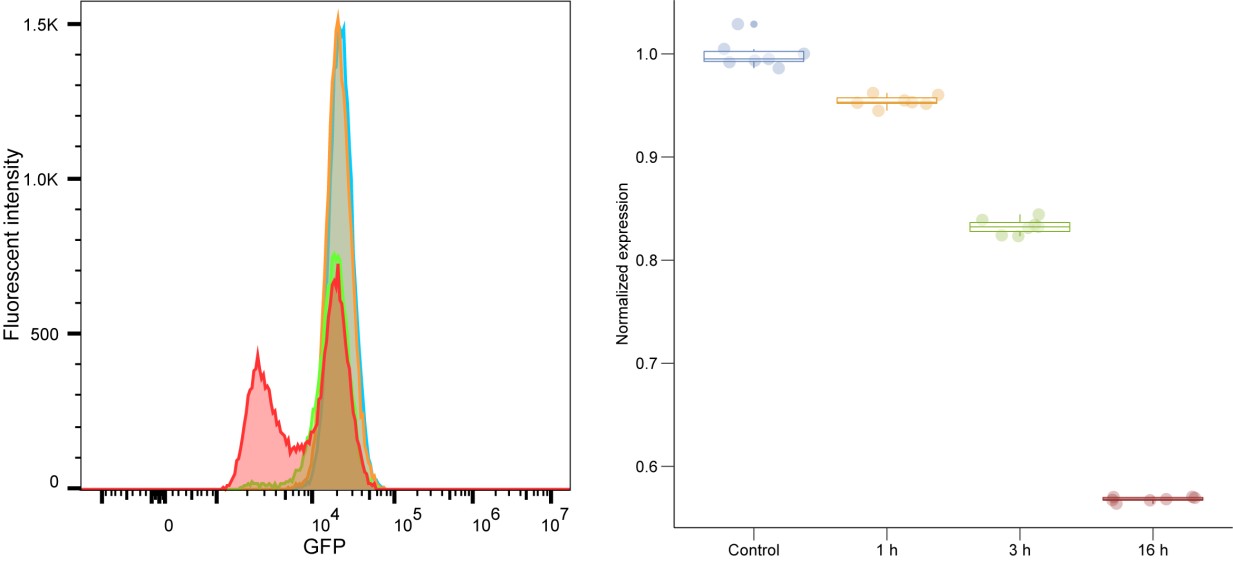

We thank the reviewer for their constructive suggestions regarding our FRAP analysis. To address the concern that the original comparison between PN and the micronuclei (MN) might have been biased by differences in bleaching areas, we performed new experiments in which both PN and MN were fully bleached within the same cells (Fig. 3A, and 3C). This approach allowed for a more direct comparison of importin α1 dynamics under equivalent conditions.

These experiments revealed a markedly slower fluorescence recovery in MN than in PN, indicating reduced nuclear import and/or recycling efficiency of importin α1 in MN. In addition, we retained our original analysis to further characterize the heterogeneous mobility patterns of importin α1 in MN, identifying three distinct mobility classes: high, intermediate, and low (Fig. 3B, and 3D). Together, these results support our observation that importin α1 mobility is restricted in MN, likely due to altered nuclear transport dynamics.

As suggested by the reviewer, we attempted partial bleaching of MN to assess intranuclear mobility. However, owing to the small size of MN, partial bleaching is technically challenging and inconsistent, with some MN recovering even during the bleaching process. Therefore, reliable quantification was not possible. For transparency, these data are provided as a Reviewer-only Figure but were not included in the revised manuscript.

Finally, while we agree that examining other nuclear transport factors (e.g., RAN, CAS, RCC1) would be informative, our study focused on importin α1 dynamics. We consider these additional factors to be important directions for future investigations.

Prior studies are referenced appropriately in general, but the authors missed some references (PMID: 32601372; PMID: 32494070; PMID: 27918550; PMID: 28738408; PMID: 28759889) that I consider key to put the present findings in frame with previous works which link the lack of structural integrity and/or aberrant DNA replication/damage responses in MN with Cchromothripsis and inflammation.

We thank the reviewer for carefully pointing out the key references that are highly relevant to framing our findings in the context of previous studies on micronuclear instability, chromothripsis and inflammation. We fully agree with this suggestion.

In the revised manuscript, we have cited these studies in both the Introduction and Discussion sections. Specifically, we incorporated these studies when discussing the structural fragility of MN, aberrant DNA replication, and the exposure of micronuclear DNA to cytoplasmic sensors, which mechanistically link MN rupture to chromothripsis and cGAS-STING-mediated immune activation. For example, we now refer to the study demonstrating RPA2 recruitment to ruptured MN in a CHMP4B-dependent manner (PMID: 32601372), reports showing defective replication and DNA damage responses in MN (PMID: 32494070; 27918550), and seminal studies establishing cGAS localization to ruptured MN and activation of innate immune signaling (PMID: 28738408; 28759889).

By incorporating these references, we more clearly position our findings that importin α1 defines a distinct subset of MN lacking access to DNA repair and sensing factors such as RAD51, RPA2, and cGAS. This contextualization emphasizes that our data add to and extend the established view that compromised MN integrity underlies chromothripsis and inflammation by identifying importin α1 as a novel marker of an alternative MN microenvironment. We are grateful for this constructive recommendation, which has allowed us to strengthen the framing of our study in the existing literature.

The figures presented in the manuscript are clear; however, where plots are included, they require appropriate statistical analysis. It is essential to display p-values on the plots or within their legends to provide readers with information regarding the significance of the results. Including this statistical information will enhance the interpretability of the data and strengthen the overall findings of the study. I recommend that the authors revise these sections accordingly before publication.

In response, we have revised the relevant figure panels and their legends to clearly display the statistical significance, including p-values, where appropriate. Specifically, we added statistical annotations (p-values or significance markers such as asterisks) directly on the plots or in the corresponding legends, and clarified the number of replicates, statistical tests used, and definitions of error bars (mean {plus minus} SD). We believe that these revisions improve the interpretability and transparency of our results and strengthen the overall presentation of the data.

__

1.) In lines 134-135, it is stated that "up to 40% of the MN showed importin α1 accumulation under both standard culture conditions and the reversine treatment (Fig. S2F)." However, Figure S2F only displays percentages for reversine-treated cells, and there is no mention in the text or figures regarding the percentage of importin α1-positive MN determined by immunofluorescence (IF) under standard culture conditions. This discrepancy should be addressed.__

Following the reviewer's comments, we revised Supplemental Fig. S2F shows a direct comparison of the proportion of importin α1-positive MN between untreated and reversine-treated HeLa cells based on indirect IF analysis. The Results section was updated accordingly (page 8, Lines 148-150): "We then examined whether reversine treatment affected the proportion of importin α1-positive MN. The results revealed that the MN formation rate for either untreated or treated cells was 36.2% {plus minus} 7.8 or 38.3% {plus minus} 8.8, respectively, with no significant difference (Fig. S2F). "

We believe that this revision addresses the reviewer's concern by providing relevant quantitative data for the untreated condition.

2.) In line 170, the authors state that "Cells in which overexpressed EGFP-importin α1 localized only in PN were excluded from the analysis (see Fig. 1E, top panels)." It is unclear why this exclusion was made. The authors should clarify whether they are referring to all constructs or only to the wild-type (WT) construct when mentioning EGFP-importin α1 localization solely in PN. This clarification is important as it may affect the results highlighted in line 173.

In this section, we aimed to clarify that the quantitative analysis focused exclusively on cells harboring MN, as the purpose of the analysis was to compare the localization of EGFP-importin α1 between MN and PN. We excluded cells that contained no MN and showed EGFP-importin α1 localization only in the PN. This criterion was consistently applied to both wild-type and mutant constructs. To avoid confusion, we have removed the sentence "Cells in which overexpressed EGFP-importin α1 localized only in PN were excluded from the analysis (see Fig. 1E, top panels)." from the revised manuscript.

3.) The statement in line 191 ("However, this antibody could not be further used in this context due to cross-reactivity with highly concentrated importin α1 in MN (Fig. S4)") is somewhat misleading. While it hints at a technical issue, it does not provide additional relevant information for understanding its implications for the rationale of the research. Moreover, Figure S4 is referenced but appears to refer specifically to panels S4D and E, which are not mentioned in the text. I recommend clarifying this point or removing it altogether.

We agree with the reviewer that the statement "However, this antibody could not be further used in this context due to cross-reactivity with highly concentrated importin α1 in MN (Fig. S4)" was not essential for understanding the rationale of our study and could be misleading. In response, we have removed this sentence from the revised manuscript, along with the corresponding Supplementary Fig. S4.

4.) Lines 197-199 contain a sentence that could be misleading and would benefit from clearer explanation. Although Figure 3D provides some clarity on this matter, no statistical analysis is included-only a bar plot is presented. A proper statistical analysis should be provided here to enhance understanding.

In the revised manuscript, we performed one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons test to evaluate the MN localization ratio of EGFP-NES between Imp-α1-negative and Imp-α1-positive MN. This analysis revealed a statistically significant difference (**p

5.) In lines 218-221, it states that importin α1 associates with euchromatin regions characterized by H3K4me3 and H3K36me3; however, Figure 4D lacks the Spearman's correlation coefficient value for H3K36me3 within the matrix. This omission needs correction.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment. As addressed in response to Major comment #4, we have substantially revised Fig. 5 and added the missing Spearman's correlation coefficient value for H3K36me3 (now shown in Fig. 5E). These revisions, together with the overall improvements to the figure, more clearly illustrate the euchromatin enrichment of importin-α1.

6.) For consistency in the experimental design aimed at identifying potential importin α1-interacting proteins, it would be more appropriate for Figures 5C/D to show IF data from MCF7 cells rather than HeLa cells.

We sincerely apologize for the misstatements in the legends of the original Fig. 5C. The correct description is that this experiment was performed using MCF7 cells, and we have revised the legend accordingly in the revised manuscript (now Fig. 6C). In addition, because the original data in Fig. 5D were obtained from HeLa cells, we repeated this experiment using MCF7 cells and replaced the panel with new data (now Fig. 6D).

7.) To substantiate claims that importin α1 inhibits RAD51 accessibility within MN, Figures 7D and E should include thorough quantitation and statistical analysis based on at least three independent experiments.

As described above, we addressed this point by adding a new quantification and statistical analysis in Fig. 7F, based on six microscopy fields across three independent experiments. This analysis directly supports our claim that importin α1 inhibits RAD51 accessibility in the MN.

We would also like to clarify that although the reviewer referred to Figs 7D and 7E, these two panels were designed to illustrate the same phenomenon-the mutually exclusive localization of importin α1 and RAD51 to distinct MN-shown in different contexts. Specifically, Fig. 7D presents examples from separate cells, each with MN containing either importin α1 or RAD51, while Fig. 7E shows a single cell containing two distinct MN, one enriched with importin α1 and the other with RAD51. Because both panels serve as illustrative examples of the same phenomenon, it would not be meaningful to quantify them independently as parallel datasets. Instead, we integrated the statistical analysis into a unified graph (Fig. 7F), which summarizes the frequency of RAD51-positive MN in relation to importin α1 status across the cell population, thereby supporting our interpretation that importin α1-positive MN represent a distinct subset that is less accessible to RAD51.

8.) The meaning of lines 336-338-"Therefore, the enrichment of importin α1 in MN, along with its interaction with chromatin, may regulate the accessibility of RAD51 to DNA/chromatin fibers in MN and protect its activity"-is unclear. I suggest rephrasing this sentence for improved clarity and comprehension.

We appreciate the reviewer's comment regarding the clarity of our statement in the Discussion (former lines 336-338). We agree that the original phrasing is ambiguous. To improve clarity and align with our results, we revised this section to emphasize that importin α1-positive MN represent a restricted environment from which DNA repair and sensing factors are excluded. Specifically, RAD51, RPA2, and cGAS showed mutually exclusive localization with importin α1, indicating that these MN are largely inaccessible to DNA-binding proteins (pages 20-21). This rephrasing removes the unclear phrase "protect its activity" and directly reflects our experimental findings, presenting a clearer interpretation that is consistent with the Results.

9.) Fig. 1D: Numbers on the y-axis are missing, x-axis labeling is too small

We appreciate the reviewer's careful examination of the figure. In the revised manuscript, we added numerical tick labels to both the x- and y-axes and increased the label font size to ensure clear readability, as shown in Fig. 1D. We also applied the same improvements to other fluorescence intensity plots, including Figs. 4A, 4B, 5A, 5B, 7H, and Supplemental Fig. S4C and S5A-S5F to ensure consistency in readability across the manuscript. We thank the reviewer for helping us improve the clarity and accuracy of our figure presentations.

10.) Fig. 1F: As the PN/MN values of the three experiments are seemingly identical (third column) the distribution of the three individual data of the PN (first column) should mirror the distribution of the three individual data of the MN (second column). The authors might want to check why this is not the case.

Upon re-examination of the source data, we identified and corrected a minor calculation error in one subset and regenerated the panel. After correction, the three independent PN/MN ratios were 3.1%, 2.9%, and 2.6%, rather than being identical. These corrected values were proportional to the corresponding PN and MN measurements and preserved the expected relationship between their distributions. Although the numerical differences were small, they demonstrated high reproducibility across independent experiments. These corrections do not alter the interpretation of Fig. 1F, and the distribution of PN/MN values is now consistent with the paired PN and MN data presented in the revised manuscript.

Significance

Micronuclei (MN) primarily arise from defects in mitotic progression and chromatin segregation, often associated with chromatin bridges and/or lagging chromosomes. MN frequently exhibit DNA replication defects and possess a rupture-prone nuclear envelope, which has been linked to genomic instability. The nuclear envelope of MN is notably deficient in crucial factors such as lamin B and nuclear pore complexes (NPCs). This deficiency may be attributed to the influence of microtubules and the gradient of Aurora B activity at the mitotic midzone, which inhibits the recruitment of proper nuclear envelope components. Additionally, several other factors may contribute to this process: for instance, PLK1 controls the assembly of NPC components onto lagging chromosomes; chromosome size and gene density positively correlate with the membrane stability of MN; and abnormal accumulation of the ESCRT complex on MN exacerbates DNA damage within these structures, triggering pro-inflammatory pathways.

The work presented by Dr. Miyamoto and colleagues reveals the abnormal behavior of importin α1 in MN during interphase. According to their findings, it is reasonable to consider importin α1 as a molecular marker for characterizing MN dynamics. Furthermore, it could serve as a potential clinical marker if the authors provide additional experiments demonstrating significantly different localization patterns of importin α1 in transformed cells (e.g., MC7, HeLa, MDA-MB-231) compared to non-transformed cells (e.g., MCM10A).

While the authors present some evidence indicating partial disruption of nuclear envelopes in MN (Figures 3 and S4), it is noteworthy that this phenomenon also occurs in importin α1-negative MN. Moreover, according to the figure legends, data for both figures originate from a single experiment. As such, convincing evidence linking the aberrant behavior of importin α1 in MN with chromothripsis processes or regulation of the cGAS-STING pathway-and its implications for genomic instability in cancer cells-remains lacking.

Overall, it is not entirely clear what significance this advance holds for the field; while there are conceptual contributions made by this work, they do not appear sufficiently robust at this time. Further research is needed to clarify these connections and strengthen their conclusions regarding importin α1's role in MN dynamics and genomic instability.

We sincerely appreciate the reviewer's thoughtful and constructive evaluation of the significance of our study. We agree that in the original submission, the conceptual contribution was not fully supported by sufficient evidence. In the revised manuscript, we have substantially strengthened our findings by incorporating new data on RPA2 and cGAS, in addition to RAD51. These results consistently show that importin α1-positive MN are largely inaccessible to multiple DNA-recognizing proteins-including DNA repair factors (RAD51 and RPA2) and the innate immune sensor cGAS-whereas importin α1-negative MN readily recruit these proteins. This broader dataset reinforces the concept that importin α defines a distinct and restricted MN subset, extending beyond our initial observation of RAD51 exclusion.

By framing importin α as a molecular marker that discriminates between functionally distinct MN environments, our study conceptually advances the understanding of MN heterogeneity. This adds to the prior literature showing that defective nuclear envelope integrity underlies chromothripsis and cGAS-STING activation and positions importin α as a new marker for identifying MN that are refractory to these DNA repair and sensing pathways. While we agree that further work is necessary to directly link importin α enrichment to downstream genomic instability or inflammation in cancer, we believe that our revised data now provide a robust foundation for future investigations.

Taken together, the revised manuscript presents a clearer and more comprehensive conceptual advance: importin α-positive MN represents a previously unrecognized molecular environment distinct from MN characterized by canonical DNA repair or sensing factors. We are grateful to the reviewer, whose constructive comments greatly improved the clarity, robustness, and overall impact of our study. We believe that these findings will be of particular interest to researchers studying the mechanisms of genomic instability, chromothripsis, and cancer biology.

Reviewer #2

Summary:

The authors have shown that Importin α1, a nuclear transport factor, is enriched in subsets of micronuclei (MN) of cancer cells (MCF7 and HeLa) and, using FRAP, has an altered dynamics in MN. Moreover, the authors have shown that these levels of Importin α1 in the MN are likely not due to its traditional role for signal-dependent protein transport, as suggested by immunofluorescence of other factors important for this function. Additionally, cargo dynamics carrying NLS or NES signals were disrupted in Importin α1-positive micronuclei. Importin α1-positive micronuclei also appear to have a disrupted nuclear envelope, potentially explaining some of these cargo disruptions. The authors also demonstrated that Importin α colocalizes with proteins important for DNA replication, and p53 signaling using RIME, followed by immunofluorescence. Lastly, the authors show that Importin α and RAD51 have mutual exclusivity in the micronuclei.

Major comments:

1) A key issue is there are very few statistical tests used in this study. It is crucial to the interpretation of the data. We strongly urge the authors to re-analyze the data using appropriate statistical analyses. Along those lines, in many figures 1 or 2 images are shown without stating how many biological or technical replicates this is representative of or showing quantification of the anlyses. In general, the authors' statements would be strengthened by showing more examples and/or stating "N" in the figure legends or supplement.

We sincerely thank the reviewer for emphasizing the importance of including sufficient statistical analyses and replication information. As noted in our response to Reviewer #1, we have carefully revised the manuscript to enhance statistical rigor and transparency throughout. Specifically, we expanded the Statistical Analysis section in the Materials and Methods section to provide a clear description of the statistical approaches used. In addition, all figure legends have been revised to explicitly state the number of biological replicates, sample sizes, statistical tests applied, and corresponding p-values or significance indicators. Representative images are consistently accompanied by quantitative analyses derived from multiple independent experiments.

We believe that these comprehensive revisions directly address the reviewer's concerns and substantially improve the rigor, clarity, and interpretability of our manuscript.

2) Using RIME and immunofluorescence, the authors identify factors that co-localize with Importin α1 in subsets of micronuclei (Figure 5), which is interesting, but there is no functional data associated with this result. Are the authors stating that these differences account for altered DNA damage or replication? It is unclear what the conclusion is beyond "some MN are different than others." Could the authors knockdown/knockout these factors to determine if they recruit Importin α1 into MN or the reciprocal? For many of these factors, they appear to be broadly present throughout the entire primary nucleus as well, indicating there is nothing unique about their MN localization.

We agree that our original RIME and indirect IF analyses were primarily descriptive and lacked functional validation. To strengthen this aspect, we added new IF and quantification data (now presented in Fig. 8) showing that importin α1-positive MN are largely mutually exclusive with DNA repair and sensing factors such as RAD51, RPA2, and cGAS, whereas importin α1 frequently co-localizes with chromatin regulators identified by RIME, such as PARP1 and SUPT16H/FACT. These findings indicate that importin α1-positive MN define a distinct molecular environment enriched in replication- and chromatin-associated regulators but inaccessible to canonical DNA repair and sensing proteins.

This combination of mutual exclusivity with DNA repair/sensing factors and frequent co-localization with chromatin regulators underscores the biological significance of importin α1 localization in MN, as it may contribute to localized chromatin stabilization through association with chromatin regulators while simultaneously restricting access to DNA repair and sensing factors. Thus, importin α1-positive MN represent a restricted subset with potential implications for genome stability and immune signaling, going beyond the descriptive notion that "some MN are different than others."

Moreover, many chromatin regulators identified by RIME contain classical nuclear localization signals (NLSs), raising the possibility that importin α1 interacts with these proteins via their NLS sequences. We fully agree with the reviewer that knockdown or knockout experiments would be highly valuable to clarify whether such interactions actively recruit importin α1 into MN or occur reciprocally, and we regard this as an important direction for future investigations.

3) In line 274, the authors state that MN highly enriched for Importin α1 inhibits RAD51 accessibility but this is an overstatement of the data. Instead, the authors show that RAD51 and importin α1 do not colocalize in micronuclei, albeit without quantification which weakens their argument. Also, the consequence of this "mutual exclusivity" is unclear. Can the authors inhibit or knockdown Importin α1 and show that RAD51 goes to all micronuclei? And how is this different than the data shown for factors in Figure 5? Some of those show colocalization with Importin α1-positive micronuclei and others do not. Could you perform live imaging of labeled Importin a1 and RAD51 and show that as Importin α1 accumulates in MN that RAD51 or other DNA repair factors are exported? An alternative experiment would be to show that the C-mutant, which is defective in nuclear export, now colocalizes with RAD51 in MN. Please reconcile this or show experiments to prove the statement above.

We agree that our original wording "inhibits RAD51 accessibility" was not sufficiently supported by direct evidence, as it was based solely on the immunofluorescence data. Therefore, we have removed this statement from the Results section of the revised manuscript. To strengthen this point, we added a quantitative analysis (Fig. 7F) showing that RAD51 signals were significantly reduced in importin α1-enriched MN.

Regarding the suggestion to perform knockdown experiments, we note that the depletion of KPNA2 (gene name of importin α1) has been reported to cause severe cell-cycle arrest (Martinez-Olivera et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2012). Consistent with these reports, we also found that siRNA-mediated knockdown of KPNA2 in our system strongly reduced MN induction upon reversine treatment, making it technically unfeasible to analyze RAD51 localization under these conditions. We also sincerely thank the reviewer for suggesting the live imaging experiments. We fully agree that such experiments would provide valuable mechanistic insights, and we regard this as an important direction for future research.

In addition, to address the reviewer's concern about other DNA repair factors, we added new data (Fig. 8) showing that importin α1-positive MN are mutually exclusive with RPA2 and cGAS. RPA2 is a canonical single-strand DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein that stabilizes exposed ssDNA and facilitates RAD51 recruitment. It has been reported to accumulate in ruptured MN in a CHMP4B-dependent manner (Vietri et al, 2020). cGAS is a cytosolic DNA sensor that detects ruptured MN and activates innate immune signaling via the cGAS-STING pathway. Together with our RAD51 results, these data show that importin α1-positive MN are consistently segregated from multiple DNA-recognizing factors, including RAD51. Simultaneously, importin α1 co-localizes with chromatin regulators identified by RIME, such as PARP1 and SUPT16H/FACT. These findings support the view that importin α1-positive MN define a distinct molecular environment enriched in chromatin regulators but largely inaccessible to DNA repair and sensing factors. While the precise mechanism remains unclear, one possibility is that importin α1-associated chromatin interactions limit the access of DNA repair and sensing proteins. However, this interpretation is speculative and requires further investigation.

4) In the Discussion, line 343-344 states that "importin α1 is uniquely distributed and alters the nuclear/chromatin status when enriched in MN," however this is not currently supported by the present data. The data presented shows correlation (albeit weak) between euchromatic modifications and Importin α1, and it does not definitively show that importin α1 is sufficient to alter the nuclear-chromatin status when enriched in the MN. More substantial experiments would be required to show whether Importin α1 plays an active role in these modifications.

Following the reviewer's suggestion, in the revised manuscript, we removed this overstatement and rephrased the relevant sections of the Discussion. Rather than implying a causal role, we now describe the mutually exclusive localization of importin α1 with DNA repair and sensing factors (RAD51, RPA2, and cGAS), emphasize its preferential association with euchromatin regions marked by H3K4me3, and note its frequent co-localization with chromatin regulators identified by RIME, such as PARP1 and SUPT16H/FACT. These findings suggest that importin α1-positive MN define a distinct subset characterized by limited accessibility to DNA repair and sensing proteins, whereas cGAS-positive ruptured MN exemplify a state in which these proteins can accumulate.

We also added a concluding statement that frames importin α1 as defining a previously unrecognized MN subset that is distinct from conventional ruptured MN. This revision provides a more accurate and appropriately cautious interpretation of our data while underscoring the conceptual advance of our study by clarifying how importin α1 localization reveals MN heterogeneity.

Minor Comments

1) Summary statement (page 3 Line 40): The use of "their" is confusing. Whose microenvironment are you referring to?

We have rephrased the sentence as follows: The accumulation of importin α in micronuclei, followed by modulation of the microenvironment of the micronuclei, suggests the non-canonical function of importin α in genomic instability and cancer development. Thank you for this useful suggestion.

2) In Abstract and introduction (page 4, Line 44 and page 5, line 59) it states that MN are membrane enclosed structures, but this is not always the case (see https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23449 as one example).

While MN are typically surrounded by a nuclear envelope at the time of their formation during mitosis, we agree that this envelope can later rupture or fail to assemble completely, thereby exposing micronuclear DNA to the cytoplasm. To clarify this point, we revised the Introduction to explicitly acknowledge that MN may lose nuclear envelope integrity, which can have important consequences for genomic instability and immune activation inflammation. Specifically, we have added the following sentence to the Introduction (page 4, lines 77-80): "The nuclear envelope of MN can be partially or completely disrupted, allowing cytoplasmic DNA sensors, such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), to access micronuclear DNA and trigger innate immune responses via the cGAS-STING pathway (Harding et al, 2017; Li & Chen, 2018; Mackenzie et al, 2017). "

We hope this addition appropriately addresses the concerns raised by Reviewer #2 while incorporating the valuable suggestions from Reviewer #1 without altering the overall structure and flow of the manuscript.

3) Given the fact that the RIME result identified proteins involved in DNA replication to be enriched with Importin α1, are these MN enriched in factors described in Fig. 5 simply localizing to MN that are in S phase, as described previously (doi: 10.1038/nature10802)?

We sincerely thank the reviewer for raising this constructive perspective regarding the potential relationship between importin α1 enrichment in micronuclei (MN) and the S phase. Our RIME analysis identified chromatin-associated proteins, such as PARP1 and SUPT16H/FACT, which are often activated during replication stress and frequently function in the S phase. However, importin α1-positive MN were not exclusively associated with S-phase-specific molecules, and our data do not indicate that these MN are restricted to the S phase.

Previous studies [e.g., (Crasta et al, 2012)] have established that MN are prone to replication defects and represent hotspots of genomic instability. The recovery of replication stress-responsive molecules, such as PARP1 and FACT, by RIME is therefore consistent with the biology of MN. Based on this valuable suggestion, we have revised the Discussion (page 19) to explicitly mention the potential involvement of replication-related proteins in importin α1-positive MN, as well as the possibility that importin α1 accumulation may contribute to replication defects in these structures. We are grateful to the reviewer for raising this important perspective, which has enabled us to place our findings in a broader mechanistic context.

We are grateful to the reviewer for this important comment, which has allowed us to place our findings in a broader mechanistic context and outline directions for future research, including testing the relationship between importin α1-positive MN and established S-phase markers such as PCNA.

4) The FRAP data is not very compelling. While it is clear there are differences between the PN and MN dynamics, what is driving these differences? Are these differences meaningful to the biology of the MN or PN? It is unclear what this data is contributing to the conclusions of the paper. Also, if the mobility of the MN is plotted on the same graph as the PN, the differences in MN mobility might not look as compelling.

We respectfully emphasize that FRAP analysis is a key component of our study, as it provides important insights into the distinct dynamics of importin α1 in MN compared to PN.

In the revised manuscript, we included new experiments (now shown in Fig. 3A and 3C) that directly compare the recovery kinetics of importin α1 in PN and MN in the same cells. By plotting the PN and MN recovery curves side by side, we aimed to improve clarity and provide a direct visualization of the pronounced differences in importin α1 dynamics between these compartments.

Our FRAP results showed that importin α1 accumulated in both PN and MN but exhibited markedly reduced mobility in MN. These findings suggest that, unlike in the PN, canonical nucleocytoplasmic recycling of importin α1 is impaired in MN. Furthermore, the reduced mobility indicates that importin α1 is stably associated with chromatin or chromatin-associated factors in MN, consistent with our additional biochemical and imaging data showing preferential association with euchromatin (e.g., H3K4me3) and chromatin regulators.

Taken together, the FRAP data provide functional evidence that complements our structural and molecular analyses, supporting our central conclusion that importin α1 accumulation in MN defines a restricted chromatin environment that influences the accessibility of DNA repair and sensing factors.

5) In Results (line 117), you state that "the cytoplasm of those cell lines emitted quite strong signals" for Importin α1, but that phrasing is a little confusing. Yes, Importin α1 is in present the cytoplasm in most cells, but it appears you are referring to the enrichment in MN. I would recommend re-phrasing this statement to make your intent clearer.

As the reviewer rightly noted, the original phrasing, "the cytoplasm of those cell lines emitted quite strong signals," was misleading, as it could suggest a broad cytoplasmic distribution of importin α1. Our observations showed that importin α1 accumulated specifically in MN located within the cytoplasm, but not in the cytoplasmic regions. To clarify this, we revised the Results section (page 7, lines 125-127) to read: " Next, we performed indirect immunofluorescence (IF) analysis on human cancer cell lines, including MCF7 and HeLa cells. Notably, we found that importin α1 accumulated prominently in MN located within the cytoplasm (MCF7 cells, Fig. 1B; HeLa cells, Fig. 1C; yellow arrowhead). " .

We believe that this revised wording more accurately reflects our findings and addresses the reviewer's concerns.

6) In Results (line 135, Figure S2E,F), the ratio of high, low or no Importin α1 intensity is confusing. Is this percentage relative to the total number of MN? It Is unclear what is meant by "whole number" of MN. Is Importin α1 intensity quantified or is it subjective?

We apologize for the confusing terminology used in the original manuscript for Supplemental Fig. S2 and thank the reviewer for pointing it out. Although the reviewer did not specifically comment on the classification of importin α1 signal intensity as "high" or "low," we recognized that this approach relied on subjective visual assessment and lacked clearly defined thresholds. To improve clarity and objectivity, we have removed this classification and now analyze importin α1 localization in MN as simply positive or negative (revised Supplemental Fig. S2E). The previous graph (original Fig. S2F) was deleted. In addition, the frequency of Importin α1-positive MN has been reported in the Results section of the main text (page 8). We believe that these revisions have improved the clarity and reproducibility of our data presentation.

7) Figure 2C is confusing. Are you counting MN with co-localization of Importin α1 and these factors? Please clarify.

Figure 2C shows the percentage of importin α1-positive MN that displayed localization of importin β1, CAS, or Ran based on IF analysis. In other words, it represents the co-localization rates of these transport factors specifically within the subset of MN positive for importin α1. To improve clarity, we revised the y-axis label in Fig. 2C to "Localization in Impα1-positive MN (%)" and modified the figure legend accordingly. We have clarified this point in the Results section (page 9). We believe that these revisions resolve the confusion and clarify the scope of the analysis.

8) Figure S3D quantification is very confusing and unclear. Also, how is this normalized? Are you controlling for total signal in each cell? And can the results of this experiment give you any mechanistic insight as to what is regulating MN localization beyond the interpretation of "MN localization is distinct from PN localization"? The "C-mutant" appears quite a bit different than the others. What might that indicate about the role of CAS/CSE1L in MN enrichment?

We apologize for the confusion caused by the quantification in the Supplemental Fig. S3D (now revised as Fig. S4D). This figure shows the relative enrichment of EGFP-importin α1 in MN compared with that in PN for wild-type and mutant constructs. To control for nuclear size, fluorescence intensity was measured using a fixed circular ROI (1.5-2.0 µm in diameter) placed in both the MN and PN of the same cell, and MN/PN intensity ratios were directly plotted for individual cells (n = 8 per condition). This procedure is described in detail in the Results section (page 10).

Regarding the C-mutant, the reduced MN/PN ratio primarily reflects increased importin α1 accumulation in the PN rather than a reduced retention in the MN. As discussed in the revised manuscript (page 18), this suggests that CAS/CSE1L-mediated nuclear export is active in the PN but may be impaired or uncoupled in the MN, possibly due to differences in nuclear envelope integrity or chromatin context. We believe that this clarification addresses the reviewer's concerns and highlights the mechanistic implications of the C-mutant phenotype.

9) For Figures 3A,B and S4, are these images of single z-slices or projections? It would be helpful to clarify for your interpretations as to whether they are truly partial or diffuse or the membrane is in another z-plane. Also, how does the localization of Importin α1 different or similar to other factors that localize to MN with a compromised nuclear envelope, such as cGAS? If it is based on epigenetic marks, it should be different than cGAS, which primarily binds non-chromatinized DNA.

We thank the reviewer for this valuable suggestion. All images shown in Figs 3A, 3B, and S4 in the original manuscript (now revised as Fig. 4A and 4B, with the original Fig. S4 omitted) were derived from single optical sections rather than projections. We would like to emphasize that similar discontinuities in signals for lamin proteins (including laminB1 and laminA/C) were consistently observed across multiple cells and independent experiments, indicating that these observations are not due to an artifact of image acquisition or a missing z-plane, but rather reflect a genuine partial loss of the MN membrane.

In contrast to cGAS, which predominantly binds non-chromatinized DNA in ruptured MN, our data indicate that importin α1 preferentially localizes to MN regions enriched in euchromatin-associated histone modifications, such as H3K4me3. The new data presented in Fig. 8 further strengthen this point by directly comparing importin α1 with DNA-recognizing proteins such as cGAS and RPA2, which preferentially localize to MN lacking importin α1. Together, these results highlight that importin α1-positive MN constitute a distinct subset characterized by chromatin-associated localization and reduced accessibility to DNA repair and sensing proteins.

10) In Results, it is unclear how Fig. 7B was calculated. Are the authors qualitatively assessing if RAD51 is there or looking for MN enrichment relative to PN? Additionally, in Fig. 7C, RAD51 localization is diffuse. It should be enriched in foci. I would recommend the authors repeat this experiment using pre-extraction then quantify RAD51 foci number and/or intensity.

For the quantification shown in Fig. 7B of the original manuscript, we acquired images containing approximately 15-50 cells per condition and counted all the micronuclei (MN) in those fields. The percentage of RAD51-positive MN relative to the total MN was calculated. In the revised manuscript, we further refined this analysis by classifying RAD51-positive MN into two categories based on signal intensity: weak (Cell #1 type) and strong (Cell #2 type). For each condition, nine independent fields were analyzed (302 MN in untreated cells and 213 MN in etoposide-treated cells). This quantification revealed that etoposide treatment preferentially increased the proportion of MN with strong RAD51 accumulation (Fig. 7C, right panels), indicating enhanced DNA damage in MN. Thus, our analysis was quantitative rather than qualitative, based on systematic counting across multiple fields.

Regarding the reviewer's suggestion of pre-extraction, we believe that this approach is technically difficult because MN are structurally fragile. Importantly, in the subset of MN with strong RAD51 accumulation, RAD51 was clearly present in foci rather than diffuse signals, as shown in the high-magnification images (Fig. 7E).

Finally, in response to Reviewer #1, we performed a new quantitative analysis (Fig. 7F) focusing on the frequency of strongly RAD51-positive MN in relation to importin α1 status. This analysis confirmed the mutually exclusive relationship between RAD51 and importin α1 in MN and further strengthened our conclusions.

11) In line 264, "notably" is misspelled.

Thank you for pointing this out. We have corrected the spelling.

12) In line 303, "scenarios" should be changed to the singular form.

Thank you for this confirmation. We have corrected this to "scenario".

13) In Figure legend, line 571-582, H3K27me3 is shown in Figure 4D, but the written legend does not mention this mark.

We have added the marks in the legend for Fig. 5E.

Significance:

Overall, this paper shows compelling evidence for micronuclear localization of regulators of nuclear export, notably Importin α1. Of note, this occurs in subsets of MN that lack an intact nuclear envelope. And while it has been appreciated that compromised micronuclear envelopes lead to genomic instability, this is one of the first that demonstrate alteration in the nuclear envelope may disrupt import or export of nuclear proteins into micronuclei.

A limitation of the study is that much of the work is based on immunofluorescence and lacks mechanism. While there is much correlative data showing that Importin α1 localizes to micronuclei with compromised envelopes, it is unclear whether Importin α1 drives micronuclear collapse or it is downstream of this process. Additionally, Importin α1 micronuclear localization anti-correlates with RAD51 but does colocalize with other DNA replication factors, yet it is unclear whether their localization is dependent on Importin α1 or its role in nuclear export. Currently, the audience for this manuscript would be focused to those interested in micronuclei. If these concerns about an active role for Importin α1 in micronuclear export are resolved, it would greatly increase the impact of this manuscript to those interested more broadly in genomic instability, DNA repair, and cancer.

We thank the reviewer for positively evaluating our study and highlighting the importance of defining the biological significance of our findings. In the revised manuscript, we incorporated new data (Fig. 8) demonstrating that importin α1-positive MN are mutually exclusive not only with RAD51 but also with RPA2 and cGAS. These results clearly establish importin α1-positive MN as a distinct subset, defined by the enrichment of chromatin-associated proteins, while being largely inaccessible to canonical DNA repair and DNA-sensing factors.

Consistent with this, our FRAP experiments and analysis of the CAS/CSE1L-binding mutant (C-mut) further indicated that the recycling dynamics of importin α1 were altered in MN compared to PN. In addition, importin α1 was enriched in lamin-deficient areas of MN, where electron microscopy revealed a fragile nuclear envelope morphology. Together with prior evidence, as discussed in the revised manuscript that recombinant importin α can inhibit nuclear envelope assembly in Xenopus egg extracts (Hachet et al, 2004), these findings raise the possibility that high local concentrations of importin α1 may actively contribute to impaired nuclear envelope formation or stability in MN.

Such a distinct MN state may have important biological consequences. By limiting the access of DNA repair and DNA-sensing proteins, importin α1 accumulation may influence chromothripsis and immune activation, which, in turn, could play a role in tumor progression and genome instability. We believe that the identification of importin α1 as a marker defining such a restricted MN environment represents a conceptual advance that extends the relevance of our study beyond the MN field to the broader areas of genome instability, DNA repair, and cancer biology. We are grateful to the reviewer for encouraging us to strengthen the framing of our work, which has helped us clarify the novelty and impact of our findings.

Reviewer #3

Summary:

This study reports that importin alpha isoforms enrich strongly in a subset of micronuclei in cancer cells and uses mutagenesis and immunostaining to define how this localization relates to importin alpha's nuclear transport function. This enrichment occurs even though importin-alpha-positive micronuclei also contain Ran and the importin alpha export factor CSE1L, indicating that importin a enrichment is not simply a consequence of the absence of components of the nuclear transport machinery that control its localization. Mutagenesis of importin a indicates that Mn enrichment persists even when the importin beta binding and NLS binding capacities of imp a are impaired. Potential importin alpha interacting proteins are identified by proteomics, although the relationship of these potential binding partners to micronucleus localization is unclear.

-

In Figure S3, the authors show that mutagenesis of importin alpha's CSE1L binding domain decreases the ratiometric enrichment in Mn vs. Pn. However, is this effect occurring because th CSE1L binding mutant decreases Mn enrichment, or increases Pn enrichment? It seems that the latter is possible based on the images shown. If the Pn specifically becomes brighter on average in cells expressing the C-mut, while Mn remain similar in fluorescence intensity, that might suggest that CSE1L has less of an effect on importin alpha export in Mn compared to Pn.

We appreciate the reviewer's insightful observations. In the revised analysis (now presented in Supplemental Fig. S4D), we quantified EGFP-importin α1 intensities in both PN and MN using fixed circular regions of interest. This revealed that the reduced MN/PN ratio observed in the CSE1L-binding mutant (C-mut) was mainly due to an increase in the PN signal rather than a decrease in the MN signal. These results are consistent with the reviewer's suggestion and indicate that CSE1L-mediated nuclear export is functional in PN but has a limited impact on MN.

Importantly, this interpretation is supported by our FRAP experiments (Fig. 3), which show that importin α1 recycles normally in the PN but exhibits markedly reduced mobility in the MN. Together with our proteomic and colocalization analyses (Fig. 6), which identified importin α1 association with chromatin regulators such as PARP1 and SUPT16H/FACT, these findings suggest that importin α1 accumulates in MN not only because the recycling machinery is uncoupled but also because it forms stable interactions with chromatin-associated proteins. As discussed in the revised manuscript, this dual mechanism provides a plausible explanation for the persistent retention of importin α1 in MN and its role in defining a distinct MN environment.

It is unclear from the text or the methods whether RIME identification of importin-alpha binding partners is performed in reversine-treated cells, which would increase the proportion of importin alpha in Mn, or in untreated cells. In either case, it seems likely that the majority of interactors identified would be cargoes that rely on importin alpha for import into the Pn. The rationale for linking these potential interactions to the Mn is unclear. While some of these factors are indeed shown enriched in Mn in Figure 5, the significance of this is also unclear. These points should be clarified.

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. The RIME assay was performed using whole-cell extracts from untreated wild-type MCF7 cells, which primarily identified importin α1-associated nuclear cargo proteins. To assess their potential relevance to MN, we screened the RIME candidates using immunofluorescence data provided by the Human Protein Atlas database and experimentally validated those showing clear MN localization by colocalization with importin α1. This two-step approach enabled us to highlight importin α1 interactors that are functionally relevant to MN biology rather than general nuclear cargoes.

In response to the reviewer's concerns, we revised the Results section to clarify this rationale. Specifically, we added the explanation that "As importin α1 interactors are typically nuclear proteins, it is plausible that they reside not only in the primary nucleus but also in the MN. To test this possibility, we screened the identified candidates for MN localization using immunofluorescence images provided by the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database (Pontén et al, 2008; Thul et al, 2017)." (page 14, lines 294-297).

This is consistent with the idea that a wide range of nuclear proteins carrying NLS motifs can recruit importin α1 into the micronuclei, where they reside. This protein-driven enrichment of importin α1 may create a restricted microenvironment in which canonical DNA repair and sensing proteins, including RAD51, RPA2, and cGAS, are excluded, thereby defining a distinct subset of micronuclei with limited genome surveillance capacity.

In Figure 6, the authors perform FRAP of importin alpha in Mn and show that it recovers much more slowly in Mn than in Pn. However, it appears from the images shown that the entire Mn was photobleached in each FRAP experiment. It thus is unclear whether the slow FRAP recovery is limited by slow diffusion of importin alpha within Mn/on Mn chromatin or impaired trafficking of importin alpha into and out of Mn. These distinct outcomes have distinct implications: either importin alpha is immobilized on Mn (eu)chromatin, or alternatively importin alpha is poorly transported into / out of Mn. This ambiguity could be resolved by bleaching a portion of a Mn and testing whether importin alpha diffuses within a single Mn.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment regarding the interpretation of FRAP data. As the reviewer rightly pointed out, the original FRAP design-where the entire MN was photobleached-does not allow for a clear discrimination between the intranuclear immobilization of importin α1 and impaired trafficking into or out of the MN.

In line with a similar suggestion from Reviewer #1, we attempted partial photobleaching of MN to evaluate whether importin α1 can diffuse within MN independently of nucleocytoplasmic transport. However, due to the small size of MN, precise targeting is technically challenging and recovery is often unreliable, with some MN even exhibiting partial recovery during the bleaching process itself. These data were not included in the revised figures; however, we provide representative examples as reviewer-only figures to illustrate these technical limitations.

To further clarify the nuclear transport dynamics of importin α1, we redesigned our FRAP experiments to fully photobleach both the PN and MN within the same cells under identical conditions. These results, presented in revised Fig. 3A and 3C, demonstrate a markedly slower recovery of importin α1 in MN compared to PN, strongly suggesting that nucleocytoplasmic recycling of importin α1 is impaired in MN. Moreover, the reduced mobility of importin α1 in the MN is consistent with stable chromatin binding, limiting its ability to diffuse freely within the nuclear space.

We believe that this additional analysis, prompted by the reviewer's comment, significantly strengthens the mechanistic interpretation of our FRAP data.

References

Crasta K, Ganem NJ, Dagher R, Lantermann AB, Ivanova EV, Pan Y, Nezi L, Protopopov A, Chowdhury D, Pellman D (2012) DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature 482: 53-58

Hachet V, Kocher T, Wilm M, Mattaj IW (2004) Importin α associates with membranes and participates in nuclear envelope assembly in vitro. EMBO J 23: 1526-1535

Martinez-Olivera R, Datsi A, Stallkamp M, Köller M, Kohtz I, Pintea B, Gousias K (2018) Silencing of the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein karyopherin a2 promotes cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in glioblastoma multiforme. Oncotarget 9: 33471-33481

Vietri M, Schultz SW, Bellanger A, Jones CM, Petersen LI, Raiborg C, Skarpen E, Pedurupillay CRJ, Kjos I, Kip E, Timmer R, Jain A, Collas P, Knorr RL, Grellscheid SN, Kusumaatmaja H, Brech A, Micci F, Stenmark H, Campsteijn C (2020) Unrestrained ESCRT-III drives micronuclear catastrophe and chromosome fragmentation. Nat Cell Biol 22: 856-867

Wang CI, Chien KY, Wang CL, Liu HP, Cheng CC, Chang YS, Yu JS, Yu CJ (2012) Quantitative proteomics reveals regulation of karyopherin subunit alpha-2 (KPNA2) and its potential novel cargo proteins in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: 1105-1122