#selbsthilfegruppeZK

hashtag for a self-help zettelkasten group

#selbsthilfegruppeZK

hashtag for a self-help zettelkasten group

https://borretti.me/article/unbundling-tools-for-thought

He covers much of what I observe in the zettelkasten overreach article.

Missing is any discussion of exactly what problem he's trying to solve other than perhaps, I want to solve them all and have a personal log of everything I've ever done.

Perhaps worth reviewing again to pull out specifics, but I just don't have the bandwidth today.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XPuqBdPULx4

Mostly this is a lot of yammering about what is to come and the trials and tribulations it's taken him to get set up for making the video tutorials. Just skip to the later videos in the series.

He did mention that he would be giving a sort of "peep show" of his note taking method, though he didn't indicate whether or not we might be satisfied with it. This calls to mind Luhmann's quote about showing his own zettelkasten being like a pornfilm, but somehow people were left disappointed.

cross reference: https://hyp.is/GFj15IcbEe21OIMwT2TOJA/niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8-3_V

9/8,3 Geist im Kasten? Zuschauer kommen. Sie bekommen alles zusehen, und nichts als das – wie beimPornofilm. Und entsprechend ist dieEnttäuschung.

https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8-3_V

I've read and referenced this several times, but never bothered to log it into my notes.

Ghost in the box? Spectators visit. They get to see everything, and nothing but that - like in a porn movie. And the disappointment is correspondingly high.

Bendat, Julius S. Principles and Applications of Random Noise Theory. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1958.

My copy of this book from 1958 has a table of contents with numberings for chapter, section, and subsections.

Eg: 1.2-1 Constant Parameter Linear Systems

Humphreys, James E. Introduction to Lie Algebras and Representation Theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 9.0. Springer, 1972. is one of the first Springer texts in my collection which has a Luhmann-esque sort of numbering system in its table of contents. Surely there must be earlier others though?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VFs3_COOMp8

He opens up saying that he uses some small plastic containers for mushrooms that he got from the supermarket for storing his notes/slips! This is definitely a unique form of zettelkasten box!

He talks about the benefits and some of the joys of using analog practices, particularly in analogy to music and arts.

"meine kleine zettelkasten show" sounds like it ought to be a Mozart compisition like Eine Kleine Nachtmusik

I’m a screenwriter. One of the reasons I use Obsidian is the ability to hashtag. It sounds so simple, but being able to tag notes with #theme or #sceneideas helps create linkages between notes that would not otherwise be linked. My ZK literally tells me what the movie is really about.

via u/The_Bee_Sneeze

Example of someone using Obsidian with a zettelkasten focus to write screenplays.

Thought the example appears in r/Zettelkasten, one must wonder at how Luhmann-esque such a practice really appears?

Is the ZK method worth it? and how it helped you in your projects? .t3_zwgeas._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } questionI am new to ZK method and I'd like to use it for my literature review paper. Altho the method is described as simple, watching all those YT videos about the ZK and softwares make it very complex to me. I want to know how it changed your writing??

reply to u/Subject_Industry1633 at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/zwgeas/is_the_zk_method_worth_it_and_how_it_helped_you/ (and further down)

ZK is an excellent tool for literature reviews! It is a relative neologism (with a slightly shifted meaning in English over the past decade with respect to its prior historical use in German) for a specific form of note taking or commonplacing that has generally existed in academia for centuries. Excellent descriptions of it can be found littered around, though not under a specific easily searchable key word or phrase, though perhaps phrases like "historical method" or "wissenschaftlichen arbeitens" may come closest.

Some of the more interesting examples of it being spelled out in academe include:

For academic use, anecdotally I've seen very strong recent use of the general methods most compellingly demonstrated in Obsidian (they've also got a Discord server with an academic-focused channel) though many have profitably used DevonThink and Tinderbox (which has a strong, well-established community of academics around it) as much more established products with dovetails into a variety of other academic tools. Obviously there are several dozens of newer tools for doing this since about 2018, though for a lifetime's work, one might worry about their longevity as products.

https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/zo96qs/sharing_the_works_of_frank_bisse/

Sharing the works of Frank Bisse

reply to: https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/zo96qs/sharing_the_works_of_frank_bisse/

I'm curious where you found the surname Bisse? Frank gives his name as Frank Antonson in his first video and uses it in places throughout some of the videos and references I've found. It's also the name used in this relatively good overview of his work: https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/nation/2017/08/18/z-youtube-retired-humanities-teacher/553192001/. I know he used the pen name Wedge in the past, so perhaps Bisse is just another of his pen names?

I'm also curious where you've pulled the idea that "All videos have the numbering of the cards as the prefix in the video title." In 7.106.1 of 5 State of the School 2019, at the opening of the video he describes his numbering system: 7.106.1 is shorthand for 7th year, 106th day, video number 1. This seems to be a chronological numbering for tracking things and not a relational sort of numbering often seen in zettelkasten contexts. When describing his index cards he indicates that he hasn't opened or looked through them in decades. If someone finds more evidence of his use of cards, I'd love pointers to those videos.

All videos have the numbering of the cards as the prefix in the video title.

Are hyperlinks needed for a Zettelkasten?

Reply to u/ManuelRodriguez331 on https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/zvvuke/are_hyperlinks_needed_for_a_zettelkasten/

Eminem would indicate it's a clear no.

By direct translation zettelkasten = slips + box. There is no word in the name to indicate links of any sort. 😁🗃️🤣

The drawers are jammed with jokes typed on 4-by-6-inch cards — 52 drawers, stacked waist-high, like a card catalog of a certain comedian’s life’s work, a library of laughs.

Joan Rivers had an index card catalog with 52 drawers of 4-by-6-inch index cards containing jokes she'd accumulated over her lifetime of work. She had 18 2 drawer stackable steel files that were common during the mid-1900s. Rather than using paper inserts with the label frames on the card catalogs, she used a tape-based label maker to designate her drawers.

Scott Currie, who worked with Melissa Rivers on a book about her mother, Joan Rivers, at the comedian’s former Manhattan office. Many of her papers are stored there.Credit...Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

Note carefully that the article says 52 drawers, but the image in the article shows a portion of what can be surmised to be 18 2-drawer cabinets for a total of 36 drawers. (14 2-drawer cabinets are pictured, but based on size and perspective, there's one row of 4 2-drawer boxes not shown.)

https://www.target.com/p/6qt-clear-storage-box-white-room-essentials-8482/-/A-80162146

6qt Clear Storage Box White - Room Essentials™<br /> Outside Dimensions: 13 1/2" x 8 1/8" x 4 5/8"<br /> Interior Dimensions at bottom: 11 1/2" x 6 3/8" x 4 3/8"<br /> Ideal for a variety of basic and lightweight storage needs, for use throughout the home<br /> Opaque lid snaps firmly onto the base and provides a grip for easy lifting<br /> Clear base allows contents to easily be viewed and located<br /> Indexed lids allow same size storage boxes to neatly stack upon each other<br /> BPA-free and phthalate-free<br /> Proudly made in the USA

Specifications<br /> Closure Type: Snap<br /> Used For: Organizing<br /> Capacity (Volume): 6 Quart<br /> Features: Portable, Lidded, Nesting, Stackable<br /> Assembly Details: No Assembly Required<br /> Primary item stored: Universal Storage<br /> Material: Plastic<br /> Care & Cleaning: Spot or Wipe Clean<br /> TCIN: 80162146<br /> UPC: 073149215284<br /> Item Number (DPCI): 002-02-9534<br /> Origin: Made in the USA<br /> Description<br /> Organize, sort and contain! The Room Essentials 6 Quart Storage Box is ideal for a variety of basic and lightweight household storage needs, helping to keep your living spaces neat. The clear base allows contents to be easily identified at a glance, while the opaque lid snaps firmly onto the base to keep contents contained and secure. Stack same size containers on top of each other for efficient use of vertical storage space. When storing items away, use good judgment and don’t overload them or stack them too high; be mindful of the weight in each box and place the heaviest box on the bottom. This storage box is ideal for sorting and storing shoes, accessories, crafts and other small items around the home and fits conveniently on 16" wire closet shelving, bringing order to closets. The overall assembled dimensions of this item are 13 1/2" L x 8 1/8" W x 4 5/8" H.

Examples of this and similar products in use as a box for zettelkasten: - https://photos.google.com/share/AF1QipN5GmVoIhCwma1czj27bXlVDKIUfbOU3a91dYuPBNZaGsEhcZYllmotxup6OxUHhA?pli=1&key=RlhXMTM0WUpuQ2hlQkdDNzA0S1BmNzVQblo4Ti1n - https://imgur.com/a/rW8TZKt

7.106.1 of 5 State of the School 2019

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lp818Ml3C2w&list=PLuJbg6eLC7Y2nU_KhrWZX8zGg-yl_L-_T

At the opening of the video he describes his numbering system: 7.106.1 is shorthand for 7th year, 106th day, video number 1. This is a chronological numbering for tracking things and not a relational sort of numbering often seen in zettelkasten contexts.

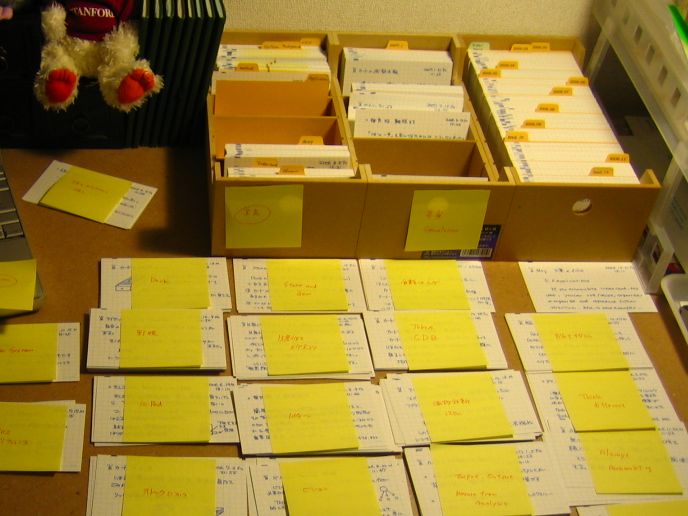

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QD_kDcepCK4

A few boxes of index cards at the start of the video.

I'm a multi-media artist, so I have many ideas about fashion pieces, artworks, music, etc. that i'd want to make. Would I plug in these ideas as 'fleeting notes' until they're more cemented? would you recommend I keep separate my 'original' ideas and the ZK note-taking system?

I gave some examples of uses in arts/media a while back that you might find interesting for your use case: https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/xdrb0k/comment/iofo5vv/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

In particular, a more commonplace book approach or something along the lines of Chapter 6 of Twyla Tharpe's book may be more useful or productive for your use case.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1fGMOEWudc1PhmLIDfj6MtRdmOVITynsHNxG-XW89Mxw/edit

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>u/FastSascha</span> in Beta Reading: Communication with Zettelkastens : Zettelkasten (<time class='dt-published'>12/23/2022 12:02:16</time>)</cite></small>

Scott is the pope of paper.

https://pkm.social/@bobdoto/109558009858082429

quote by Bob Doto. :)

as long as you operate within theframework of the four principles I’m introducing now

Thus far, Scheper has only been making the argument to do as I say because I know best. He's not laying out the reasons or affordances that justify this approach.

In this second principle it's ostensibly just "the possibility of linking", but this was broadly done previously using subject headings or keywords along with indices and page numbers which are logically equivalent to these note card addresses.

TRUE

why keep harping on this framing?

“The florilegium was a type of ‘double memory’ towhich scholars could resort anytime their personal memory failed, the filingcabinet behaves as a true communication partner with its own idiosyncrasiesand its own opinions.”31

I'll have to look into this argument as it feels dramatically false to me.

The only way I can see this is if one only uses their commonplace for excerpts and no other notes, a pattern which may have been the case for some, but certainly not all.

Yet, there are shortcomings of commonplace books. They embody that of a“subsidiary memory,” whereas the Antinet is more than this. The Antinet isa second mind, an equal.

Why though? The slight difference in form doesn't account for any differences claimed here.

The limitations of commonplacebooks centers around the following: they only enable short-term knowledgedevelopment. They do not cater to allowing thoughts to evolve over time,infinitely. They do not allow for the infinite internal branching and expansionof ideas.

sigh

This is untrue in practice. They can evolve, they just do so in different ways. Prior to Luhmann's example, they have done so for centuries.

beliefs

belief is a charged word when attempting to build systems for uncovering truths...

I hope I wouldn’t call it a wiki!

There's some flawed logic here in that Ward Cunningham outlined his version of a wiki and others who created versions thereafter modified and potentially expanded on that original "definition". We now have a general consensus of a wiki, but it's not necessarily the same for everyone. Scheper doesn't leave any fungible room in the semantics of his argument here and thereby forces one into a practicing the "one true way", which doesn't exist as even Luhmann's own practice varied over time.

Even thoughsuch apps are thought of as a Zettelkasten, the magic that Luhmann builtinto his system is lost.

I'm not a fan of the magic framing here and I'm not really sure that Luhmann consciously designed or built his system to do this. Prior systems had these "magical" features before Luhmann's.

fundamental truth

Harnessing the dictionary into fronting for his zettelkasten religion?

Zettelkasten, which in American English means notebox, and in Euro-pean English translates to slip box.

What really supports this distinction? The closest historical American English translation is probably "card index" from the early 1900s while the broader academic historical translation is "slip box".

“I first make a plan of what I am going to write,and then take from the note cabinet what I can use.”60

source:

60 Hans-Georg Moeller, The Radical Luhmann (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 11.

I rather like the phrase "note cabinet" which isn't used often enough in the zettelkasten space. Something more interesting than filing cabinet which feels like where things are stored to never be seen again versus a note cabinet which is temporary and directed location storage specifically meant for things to actively be reused.

the Antinet can serve both states. It can assist someone who’s in thegrowth state (without a clear end goal), and it can also assist someone who’sin the contribution state (with a clearly defined book or project).

This could be clearer and "growth state" and "contribution state" feel like jargon which muddles:

two of the broad benefits/affordances of having a zettelkasten: - learning and scaffolding knowledge (writing for understanding) - collecting and arranging material for general output

you’re doing things the old way,the hard way, the true way.

note the pathos along with a bit of religious zeal here about the "true way".

“I started my Zettelkasten,because I realized that I had to plan for a life and not for a book.”5

from Niklas Luhmann, Niklas Luhmann Short Cuts (English Translation), 2002, 22.

People are fascinated with how Luhmann became a book-writing academicresearch machine. The answer? The Antinet.

He highlights this here because it seems convenient to his thesis about a "true way", but Scheper has also mentioned in other venues that it was Luhmann's tenacity of working at his project that was largely responsible for his output.

I believe he made that statement in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XgMh6iuFbT4

Goitein accumulated more than 27,000 index cards in his research work over the span of 35 years. (Approximately 2.1 cards per day.)

His collection can broadly be broken up into two broad categories: 1. Approximately 20,000 cards are notes covering individual topics generally making of the form of a commonplace book using index cards rather than books or notebooks. 2. Over 7,000 cards which contain descriptions of a single fragment from the Cairo Geniza.

A large number of cards in the commonplace book section were used in the production of his magnum opus, a six volume series about aspects of Jewish life in the Middle Ages, which were published as A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza (1967–1993).

https://genizalab.princeton.edu/resources/goiteins-index-cards

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>u/Didactico</span> in Goitein's Index Cards : antinet (<time class='dt-published'>12/15/2022 23:12:33</time>)</cite></small>

“I have a trick that I used in my studio, because I have these twenty-eight-hundred-odd pieces of unreleased music, and I have them all stored in iTunes,” Eno said during his talk at Red Bull. “When I’m cleaning up the studio, which I do quite often—and it’s quite a big studio—I just have it playing on random shuffle. And so, suddenly, I hear something and often I can’t even remember doing it. Or I have a very vague memory of it, because a lot of these pieces, they’re just something I started at half past eight one evening and then finished at quarter past ten, gave some kind of funny name to that doesn’t describe anything, and then completely forgot about, and then, years later, on the random shuffle, this thing comes up, and I think, Wow, I didn’t hear it when I was doing it. And I think that often happens—we don’t actually hear what we’re doing. . . . I often find pieces and I think, This is genius. Which me did that? Who was the me that did that?”

Example of Brian Eno using ITunes as a digital music zettelkasten. He's got 2,800 pieces of unreleased music which he plays on random shuffle for serendipity, memory, and potential creativity. The experience seems to be a musical one which parallels Luhmann's ideas of serendipity and discovery with the ghost in the machine or the conversation partner he describes in his zettelkasten practice.

At Ipswich, he studied under the unorthodox artist and theorist Roy Ascott, who taught him the power of what Ascott called “process not product.”

"process not product"

Zettelkasten-based note taking methods, and particularly that followed by Luhmann, seem to focus on process and not product.

Reply to:

Who is Zettelkasten note-taking system for? <br /> u/Beens__<br /> https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/zhyu5i/who_is_zettelkasten_notetaking_system_for/

Perhaps your use case may benefit from knowing the longer term outcomes of such processes, particularly as they relate to idea generation and innovation within your areas of interest? Keeping notes which you review over periodically and between which you create potential links will help to foster more productive long term combinatorial creativity, which will help you create new and potentially useful ideas much more quickly than blank page-based brainstorming.

Her method was much more ad hoc than the more highly refined methods of Luhmann which allowed him to write, but perhaps there's something you might appreciate from the example of the character Tess McGill in the movie Working Girl. Even more base in practice is that of Eminem, which shows far less structure, but could still have interesting long term creativity effects, though again, it bears repeating that one should occasionally revisit their notes (even if they're only in "headline form") in attempts to refresh their memory and link old ideas to new to generate completely new ideas.

This is about as close to the form factor of Niklas Luhmann's own zettelkasten box as I've seen.

I published an article about the Zettelkasten Method in my blog .t3_zgx3pv._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/I_saw_the_Aleph<br /> https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/zgx3pv/i_published_an_article_about_the_zettelkasten/

Thanks for adding to the tradition in another language. This is great.

I'm obviously not a fan of the commonly held Luhmann "zettelkasten origin myth", but since you don't cite a source for "otros métodos de tomar notas similares se originan en el siglo XVII" (translation: other similar note taking methods in the 17th century), I'm curious what and potentially who you're referring to here? I've seen a handful of online sources nebulously mention this same 17th century time period without any specific evidence, so I'm curious if you're following that crowd, or if there's something more specific you have in mind or could point to from a historical standpoint?

A nice overview of Zettelkasten space written in Spanish. A few quirks to be found, but generally sound.

el bocho

New Spanish to me, but ostensibly, the brain, cerebrum, or perhaps the slang I saw of "brainbox".

Perhaps "brainbox" could be an interesting alternate English translation of zettelkasten?

Después de esta historia superficialmente narrada por mí, usted se preguntará, "Y entonces, a cual debo seguir?" A ninguno. Hay un problema en nuestra sociedad, que también se extiende hasta el Zettelkasten: nos hemos fanatizado. Hemos hecho nuestras decisiones políticas, sociales, sexuales, etc., como la esencia de nuestra persona. Me gustaría expandir en ese tema en un futuro artículo, pero por ahora nos importa como eso se relaciona con la elección del zettelkasten: hay peleas y discusiones violentas entre los seguidores de Scheper, los de Ahrens, los digitales, etc. Hay una gran radicalización y tribalismo, evitando la discusión crítica y el discordar intelectual. Y no podemos ser así. Personalmente, el zettelkasten que uso actualmente es más basado en el de Scheper, pero aún así veo a los otros, leo a Ahrens, etc., todo para tener una visión completa y variada de lo que es el Zettelkasten.

Facundo Macías notices, as have I, a semblance of internecine almost religious/fanatical war between various note taking camps.

To get away from these we should instead on specific processes, their affordances, and their potential emergent outcomes in individual use. Most people begin these entrenched thoughts based on complete lack of knowledge. Few have practiced some of the broader methods for long enough to get to potential emergent properties.

La gente se enfocó mas en el brillo que en la substancia.

People focused more on the shine than the substance.

This is an excellent summary of the space since broadly 2018ish, especially from my observations of those online.

A pesar de que la variante moderna fue creada por Luhmann, las "máquinas de pensamiento" y otros métodos de tomar notas similares se originan en el siglo XVII.

I've now seen a handful of (all online) sources quote a 17th Century origin for similar note taking methods. What exactly are they referring to specifically? What are these sources? None seem to be footnoted.

La efectividad de este sistema no se basa en la ética de trabajo enfermiza de su creador, y si en su similitud con el funcionamiento de nuestro cerebro.

Though to a great extent, his work ethic was really key to his output, something which was facilitated by his method.

Another example of building the myth of the method while sidelining the ethic which could be paired with it.

A pesar de que la administración sistemática del conocimiento no tiene orígenes recientes, el referente más común es el tema es el sociólogo alemán Niklas Luhmann, creador del Zettelkasten.

Translation:

Although the systematic administration of knowledge does not have recent origins, the most common referent on the subject is the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, creator of the Zettelkasten.

Happy Publication day! .t3_zgvcqh._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } I’m honestly so happy for Scott. It’s so exciting to know his book will finally be published and available today. Looking forward to securing my copy. ☺️ I’ve been quietly following Scott’s YouTube page and delighted to see it thriving. Best wishes Tim

reply to: https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/zgvcqh/happy_publication_day/

I already have an advanced digital copy, but honestly can't wait for the analog (and therefore "true copy") to be available for order and on my doorstep.

When are we going to see the link to order it?!? Don't think I'm just sitting around here holding my breath waiting to order this... sometimes I turn blue and fall off my chair 😰

Seriously though. Congratulations Scott!

Hopefully I'll see everyone at the start of the book club tomorrow: https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/zbibue/book_club_reading_scotts_book/

Thank you - I'm impressed, once again.I still find it baffling that the evolutionary tree of zettelkasten practices doesn't seem to show some sort of Cambrian explosion starting directly with Luhmann. There are people around him, eyewitnessing a productivity of barbaracartlandian proportions, and no one seems to make relevant attempts at imitating and adapting his specific methods? - I would like to understand the reasons for this.PS: Do you know the interview (five short parts, in German) the Suhrkamp publishing house has conducted with Andre Kieserling, Luhmann's successor at Bielefeld University, and Johannes Schmidt, the zettelkasten curator? https://youtu.be/q0LdmKMbJCw - I haven't found it in your hypothes.is annotations.Btw, I'm living in Stuttgart near Marbach, and after visiting the 2013 exhibition with its perenially inspiring title "Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie" and reading its catalogue, I've sent my copy to Professor Kuehn. I miss his Taking Note blog.

reply to https://www.reddit.com/user/thomasteepe/

Luhmann's method is certainly an evolution on prior methods, but only has a few differences. Sadly there aren't a broader array of other options that are open in the solution space to create an actual Cambrian explosion here. At the end of the day, one still has to do actual reading, note taking, thinking, and work to make the system go. It this hurdle of work that most often dampens people's spirits and despite it's ability to be more easily sustainable, it's really not very sexy, so people move on to the next shiny, new thing.

I'm aware of that series of videos and a few others, though my German is almost non-existent which makes them a slow slog. I suppose I should use Google's auto-transcription/translation, but that often muddies things further. I've had a few people translate pieces of things like that for me, but it becomes cost prohibitive after a while.

I wish Manfred Kuehn had left his site up, but I understand why he did it. I still delve back into Archive.org every now and then to find new things. If I had some extra time, I'd contact him to see if he'd be willing to publish archived versions of his blog as a book and do the collation/editing to get it out, but it's a lot of work, even with large portions automated.

One of these days I'll find a copy of the Marbach catalog to read...

Based on Luhmann's ZKII 9,8.3 (aka The Ghost in the Machine) and various other video and anecdotal sources, his colleagues saw his system and generally didn't care. His influence has primarily only been influential after-the-fact beginning online with mentions by Manfred Kuehn after 2007 with more interest following the Marbach zettelkasten exhibition in 2013 and the launch of zettelkasten.de. You're living amidst his greatest influence on the space, particularly asking this question just two days before Scott Scheper's book Antinet Zettelkasten, focusing on the specifics of Luhmann's method, is set to be released.

With respect to zettelkasten, I would posit that it was Luhmann himself who was actually standing on the shoulders of other giants which preceded him in these broader traditions including Desiderius Erasmus, Rudolph Agricola, Phillip Melanchthon, Konrad Gessner, John Locke, Ernst Bernheim, Charles Langlois, Charles Seignobos, Antoine Sertillanges, Beatrice Webb, Johannes Heyde, and C. Wright Mills, etc. See: https://boffosocko.com/2022/10/22/the-two-definitions-of-zettelkasten/ for more on the history here.

While I'm thinking about influence, has anyone named their children after the method yet? Is there a baby named Slip, Zeke, or Luhmann in honor yet? Perhaps this is the week that may have happened? 😉

I was pretty skeptical of the #zettelkasten method at first as it felt like yet another data hoarding hobby during the first weeks; but with a relatively large base of notes available, it’s in fact really useful and “works as intended” (or at least works as Luhmanns essay described how it should work).

https://emacs.ch/@thees/109474759959223870

Anecdotal evidence of time to usefulness.

The History of Zettelkasten The Zettelkasten method is a note-taking system developed by German sociologist and philosopher Niklas Luhmann. It involves creating a network of interconnected notes on index cards or in a digital database, allowing for flexible organization and easy access to information. The method has been widely used in academia and can help individuals better organize their thoughts and ideas.

https://meso.tzyl.nl/2022/12/05/the-history-of-zettelkasten/

If generated, it almost perfect reflects the public consensus, but does a miserable job of reflecting deeper realities.

Aby Warburg and his son Max Adolph in Warburg's study in Hamburg, 1917. © Warburg Institute, London.

http://www.engramma.it/eOS/index.php?id_articolo=3986

Appears to be a row of slip boxes behind Aby Warburg in this photo of his study in Hamburg from 1917.

Dr James Ravenscroft @jamesravey@fosstodon.orgFollowing on from my first week with hypothes.is I decided to integrate my annotations into #Joplin so that I have tighter integration of my literature + permanent notes. I've built a VERY alpha Joplin plugin that auto-imports hypothes.is annotations + tags to joplin by following your user atom feed https://brainsteam.co.uk/2022/12/04/joplin-hypothesis/ #PKM #ToolsForThought #hypothesis

This generally fits my criteria for submission as an example to https://boffosocko.com/2022/07/12/call-for-model-examples-of-zettelkasten-output-processes/

This is the absolute hardest part of the writing process, in my mind. The most exciting, too, because you’re never quite sure where it’s going to end up.

Anecdotal evidence that categorizing and arranging index cards/ideas for a writing project for subsequent writing is one of the most difficult portions of the process.

Niklas Luhmann subverted portions of this by pre-linking his ideas together either in threads or an outline form as he went.

https://github.com/soulwire/WTFEngine

This could be used to generate a zettelkasten card website....

https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/z3f8kb/oblique_strategies_a_custom_zettelkasten_for/

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt published a card index of un-numbered and purposefully unordered ideas in 1975 as a tool for increasing creativity. They called it "Oblique Strategies". Each card contained an aphorism for helping one to reframe their approach to problems or questions they faced.

Black box with cards containing aphorisms to help increase creativity. Photo by V&A Images from the David Bowie Archive.

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oblique_Strategies<br /> Canonical site with complete list of versions: http://www.rtqe.net/ObliqueStrategies/OSintro.html

ZK practitioners might profitably have a subsection in their box with these strategies to help themselves randomly increase their own creativity while working either inside or outside of their boxes. Potentially useful for writing, music, art, etc.

Article recommended by @wfinck. Based on backlinks, look like the author may be using Obsidian or Notion and syncing into Dropbox to create free published version of notes

https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/wzblc9/card_storage/

This page has links to some of the most common zettelkasten boxes and manufacturers mentioned on the r/antinet Reddit.

https://www.staples.com/Vaultz-Locking-4x6-Index-Card-Cabinet-Double-Drawer-Black/product_2229125

4 x 6" Index card filing cabinet; 2 drawers, with lock

$85.99 from Staples on 2022-11-21

2 drawer box for 4 x 6" index cards.

STEELMASTER by MMF Industries 263644BLA Index Card File Holds 400 4 x 6 cards, 6 3/4 x 4 1/5 x 5

https://www.newegg.com/p/N82E16848998233

metal box for 4 x 6" index cards

https://www.ikea.com/us/en/p/kuggis-box-with-lid-transparent-black-00514033/#content

7 x 10.25 x 6"

This is big enough and just about the perfect size for 4 x 6" index cards. The lid has a slight indent to make it easily stackable.

danielsantos @chrisaldrich thanks for sharing… personally, I tend to associate ZK with Luhman. But I’ll read your shared article later to broaden my perspective :)

@danielsantos Almost everyone in the space exclusively associates ZK with Luhmann, in part because of the use of the foreign (unfamiliar) German word and the lost cultural memory of the use of card indexes as note taking tools or as commonplace books in index card form. Hopefully we can change this misperception which also opens up these practices to a lot more people with a lot less confusion.

Forrest Perry, philosophy professor at Saint Xavier University

https://www.sxu.edu/directory/cas/philosophy/forrest-perry.aspx

https://zettelkasten.social/about

Someone has registered the domain and it is hosted by masto.host, but not yet active as of 2022-11-13

Something @chrisaldrich mentioned on Reddit as examples of someone selling niche Zettelkasten decks. Seem more like protocol-kasten decks to aid problem-solving in specific contexts.

Zettelkasten as a product?! .t3_xsoaya._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

@chrisaldrich's post on "pip decks". They seem less like Zettelkasten decks and more like protocol-kastens (think of a better name for this)

Seem poor for knowledge generation (Zettelkasten) and recollection (Anki), but may be useful for specific contexts of problem-solving (even in ill-defined problem spaces).

A template used by @wfinck to make this note in his public knowledge garden (ie, Zettelkasten notes with a displayed graph view of them)

Origin of Robert Greene's (May 14, 1959 - ) note taking system using index cards:<br /> Greene didn't recall a specific origin of his practices, but did mention that his mom found some index cards at his house from a junior high school class. (Presuming a 12 year old 7th grader, this would be roughly from 1971.) Ultimately when he wrote 48 Laws of Power, he was worried about being overwhelmed with his notes and ideas in notebooks. He naturally navigated to note cards as a solution.

Uses about 50 cards per chapter.

His method starts by annotating his books as he reads them. A few weeks later, he revisits these books and notes to transfer his ideas to index cards. He places a theme on the top of each card along with a page number of the original reference.

He has kept much the same system as he started with though it has changed a bit over time.

You're either a prisoner of your material or a master of your material.

This might not be the best system ever created, but it works for me.

When looking through a corpus of cards for a project, Robert Greene is able to make note of the need to potentially reuse a card within a particular work if necessary. The fact that index cards are inherently mobile within his projects make them easy to move and reuse.

I haven't heard in either Robert Greene or Ryan Holiday's practices evidence that they reuse notes or note cards from one specific project to the next. Based on all the evidence I've seen, they maintain individual collections for each book project for which they're developing.

[...] like a chameleon [the index card system is] constantly changing colors or [like] something that's able to change its shape at will. This whole system can change its shape as I direct it.

Robert Green appears to use a Globe-Weis/Pendaflex Fiberboard Index Card Storage Box, 4 x 6 Inches, Black Agate (94 BLA) to store his index card-based notes.

How I Write My Books: Robert Greene Reveals His Research Methods When Writing His Latest Work, 2020. timestamp 0:00:30.

Robert Greene: (pruriently) "You want to see my index cards?"<br /> Brian Rose: (curiously) Yeah. Can we?? ... This is epic! timestamp

A beautiful example of a note that imbeds core zettels that simultaneously make connections within a Zettelkasten. Each page for a note displays the network of notes and their connections. The website is based on an open-source template

The source code for the site is here

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xbUEa9B0wLM

This appears like it might fit the bill for my Call for Model Examples of Zettelkasten Output Processea

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Eleanor Konik</span> in The Konik Method for Making Useful Notes (<time class='dt-published'>11/07/2022 12:03:38</time>)</cite></small>

Inevitably, I read and highlight more articles than I have time to fully process in Obsidian. There are currently 483 files in the Readwise/Articles folder and 527 files marked as needing to be processed. I have, depending on how you count, between 3 and 5 jobs right now. I am not going to neatly format all of those files. I am going to focus on the important ones, when I have time.

I suspect that this example of Eleanor Konik's is incredibly common among note takers. They may have vast repositories of collected material which they can reference or use, but typically don't.

In digital contexts it's probably much more common that one will have a larger commonplace book-style collection of notes (either in folders or with tags), and a smaller subsection of more highly processed notes (a la Luhmann's practice perhaps) which are more tightly worked and interlinked.

To a great extent this mirrors much of my own practice as well.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gershom_Scholem

Known for having a large zettelkasten.

And this is the art-the skill or craftthat we are talking about here.

We don't talk about the art of reading or the art of note making often enough as a goal to which students might aspire. It's too often framed as a set of rules and an mechanical process rather than a road to producing interesting, inspiring, or insightful content that can change humanity.

You cannot followrules you do not know. Nor can you acquire an artistic habitany craft or skill-without following rules. The art as something that can be taught consists of rules to be followed inoperation. The art as something learned and possessed consists of the habit that results from operating according to therules.

This is why one has some broad general rules for keeping and maintaining a zettelkasten. It helps to have some rules to practice and make a habit.

Unmentioned here is that true artists known all the rules and can then more profitably break those rules for expanding and improving upon their own practice. This is dramatically different from what is seen by some of those who want to have a commonplace or zettelkasten practice, but begin without any clear rules. They often begin breaking the rules to their detriment without having the benefit of long practice to see and know the affordances of such systems before going out of their way to break those rules.

By breaking the rules before they've even practiced them, many get confused or lost and quit their practice before they see any of the benefits or affordances of them.

Of course one should have some clear cut end reasons which answer the "why" question for having such practices, or else they'll also lose the motivation to stick with the practice, particularly when they don't see any light at the end of the tunnel. Pure hope may not be enough for most.

https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/848/zettelizers

A thread about what to call those who have a zettelkasten or those who practice the method.

Zettelphile

This also has a nod to the idea of "filing". 😁

Being an English only speaker I love the mystery invoked by the German term "Zettelkasten".

Example of someone who sees "mystery" in the idea of Zettelkasten, which becomes part of the draw into using it.

https://www.vaultz.com/vaultz-vz01395-black-locking-4x6-index-card-cabinet-double-drawer

These are the type used by various people including Scott P. Scheper.

N.B. presuming the 4 1/8" H dimension is even the outer dimension, this means that one can't easily keep tab cut dividers which often go from 4 3/8" to 4 1/2" tall in these boxes with the lids on properly.

Instead, one may prefer their slightly larger microfiche boxes which go up to 4 3/4" which should also presumably fit their microfiche divider guides for sectioning one's work.

Another subtle difference in these two boxes is that the smaller is 60-pt paper versus 40-pt for the larger microfiche box, which means that while sturdy, isn't quite as sturdy.

These should easily fit 4 x 6" index cards as well as card dividers with taller tabs which commercially don't often get taller than 4 1/2".

See also microfiche divider guides.

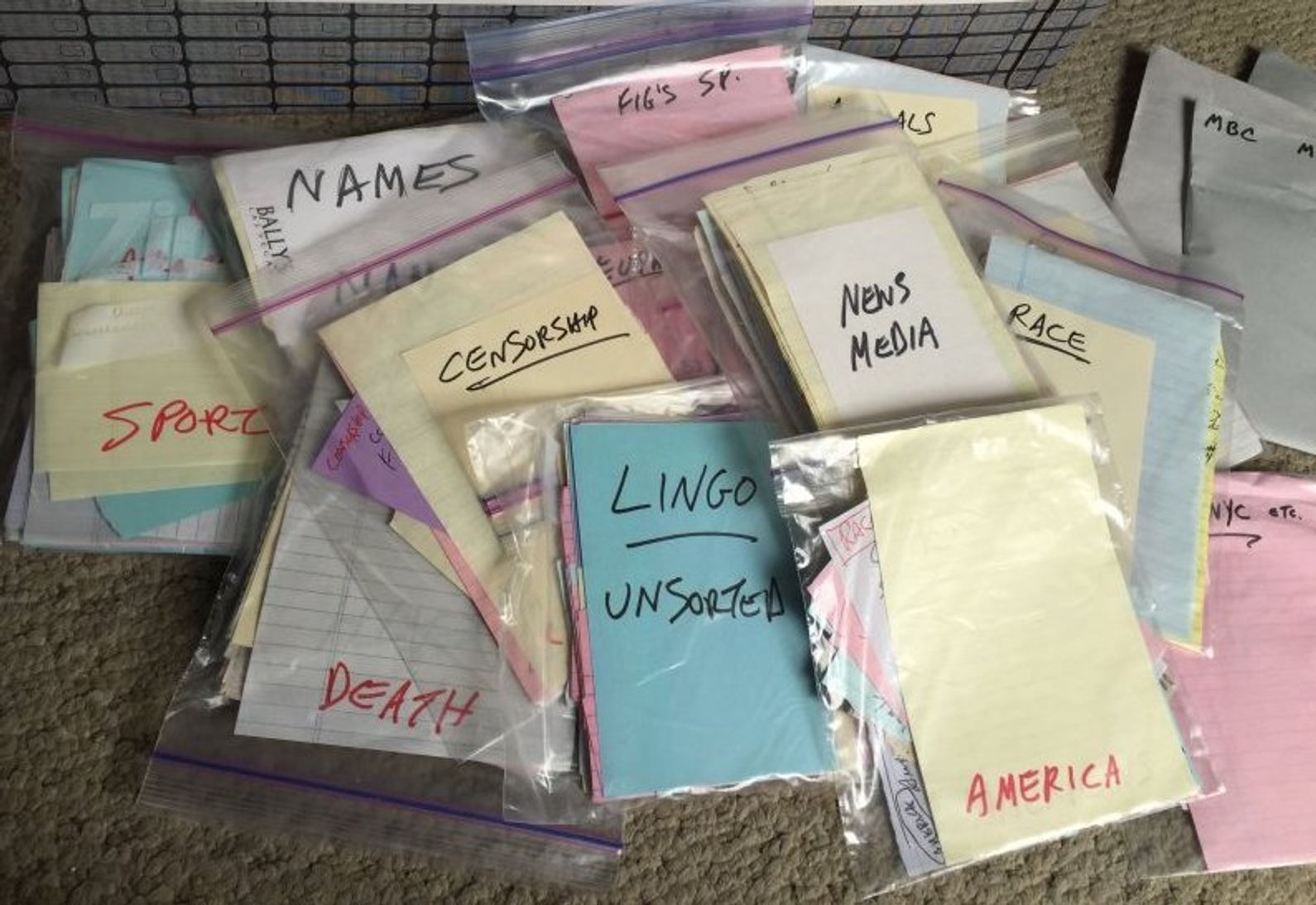

Carlin’s bags of categorized ideas, from the archives of George Carlin

George Carlin kept his slips (miscellaneous scraps of collected paper with notes) sorted by topic name in Ziploc bags (literally that specific brand given the photo's blue/purple signature on the bag locks).

This is similar to others, including historian Keith Thomas, who kept his in labeled envelopes.

Oppenheimer, Billy. “The Notecard System: Capture, Organize, and Use Everything You Read, Watch, and Listen To.” Billy Oppenheimer (blog), August 26, 2022. https://billyoppenheimer.com/notecard-system/.

Tiago’s methodology is app-agnostic. He’s a systems and principles kind of thinker, so even though I use physical notecards, his work has influenced the evolution of my processes.

Billy Oppenheimer indicates that Tiago Forte's systems and methods have influenced the evolution of his own note taking process.

Robert Greene’s notecards

Looks kind of like Billy Oppenheimer's box choice is heavily influenced by Robert Greene's.

I review the cards way more than I originally thought was necessary. Almost daily, I engage with the boxes in one way or another.

Oppenheimer interacts with his zettelkasten almost daily. He reviews them more often than he originally thought he would.

Throughout this piece Oppenheimer provides examples of notes he wrote which eventually made it into his written output in their entirety.

This has generally been uncommon in the literature, but is a great form of pedagogy. It's subtle, but it makes his examples and advice much stronger than others who write these sorts of essays.

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>Can we all agree that Zettelkasten note-taking is probably WAY more complexity than we need as creators?<br><br>Here's how to take the best parts & leave the rest to the academics pic.twitter.com/LFnAeBkbpG

— ⚡️ Ev Chapman 🚢 | Creative Entrepreneur (@evielync) February 21, 2022

raphy. Surely the fault of that savant was not neglecbut over-confidence in the virtue of the fiche, and the true morthat there is no necessary salvation in the fiche and the card-indTh

Surely the fault of that savant was not neglect, but over-confidence in the virtue of the fiche [index card], and the true moral is that there is no necessary salvation in the fiche and the card-index [aka zettelkasten].

Here the author is referencing part of the preface of Anatole France's book Penguin Island (1908) where a scholar drowns in a whirlpool of index cards.

es the sad fate of M. Fulgence Tapir to his neglecting the mechaniside of historiography.

neglecting the mechanical side of historiography

the mechanical side of historiography is a round about way of saying note taking using a card index or zettelkasten.

This is a doctrine so practically important that we could have wismore than two pages of the book had been devoted to note-takiand other aspects of the " Plan and Arrangement of CollectionsContrariw

In the 1923 short notices section of the journal History, one of the editors remarked in a short review of "The Mechanical Processes of the Historian" that they wished that Charles Johnson had spent more than two pages of the book on note taking and "other aspects of the 'Plan and Arrangement of Collections'" as the zettelkasten "is a doctrine so practically important" to historians.

T., T. F., A. F. P., E. R. A., H. E. E., R. C., E. L. W., F. J. C. H., and E. J. C. “Short Notices.” History 8, no. 31 (1923): 231–37.

Zettelkasten for technical sciences .t3_yibchw._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to: https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/yibchw/zettelkasten_for_technical_sciences/

Presumably you've been the member of or seen a journal club/discussion group for scientific articles, and if not, you could start your own journal club (with yourself) using a zettelkasten by excerpting ideas from what you read, annotating them, writing down open questions, thoughts about what researchers get right/wrong, what could be done better, etc. A zettelkasten practice can be highly fruitful in the sciences. Carl Linnaeus, Newton, and Leibnitz (among many others) had similar looking practices.

Sascha Fast has translated section 9/8 of Luhmann's zettelkasten into English.

https://zettelkasten.de/posts/luhmanns-zettel-translated/

Sascha's German to English translation of Luhmann's zettelkasten section ZK II / 9/8.

https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8_V

Topic: Communication with the Zettelkasten: How to get an adequate partner, junior partner? – important after working with staff becomes more and more difficult and expensive. Zettel’s reality

The best and most challenging communication partner you may experience is a version of your past self. A searchable set of notes is the closest approximation of this one is likely to find.

Zettelkasten with the complicated digestive system of a ruminant. All arbitrary ideas, all coincidences of readings, can be brought in. The internal connectivity then decides.

another in a long line of using analogizing thinking to food digestion.... I saw another just earlier today.

On the general organisation of memory see Ashby 1967, p103. It is therefore important that one is not dependent on a myriad of point-by-point accesses, but to be able to rely on relations between notes, i.e. on references that make more available at once than one has in mind when following a search impulse or fixating on a thought

Fascinating to see Ashby pop up in Luhmann's section on zettelkasten in part because Ashby had a similar note taking practice, though part notebook/part index card based, and was highly interested in systems theory.

Pomeroy, Earl. “Frederic L. Paxson and His Approach to History.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 39, no. 4 (1953): 673–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/1895394

read on 2022-10-30 - 10-31

After his retirement in 1947 the Carnegie Corporation of New York persuadedhim to write a history of American state universities, which came to interest him in-tensely. At the end of a year he had written half of the book and sorted his lastnotes. He notified the university administration that he was unable to complete thejob before leaving his study for the hospital where he died, October 24, 1948. Thevolume is being completed by one of his students, Professor Walton E. Bean of theUniversity of California.

Even following his retirement in 1947, Paxson continued to take notes specifically on education for a project which he never got to finish before he died in hospital on October 24, 1948.

Paxson wrote several unusually sharp reviews of books by Mc-Master, Rhodes, and Ellis P. Oberholtzer, historians whose methodshave been compared with his own

Examples of other historians who likely had a zettelkasten method of work.

Rhodes' method is tangentially mentioned by Earle Wilbur Dow as being "notebooks of the old type". https://hypothes.is/a/PuFGWCRMEe2bnavsYc44cg

the writer of "scissors and paste history" ;

One cannot excerpt their way into knowledge, simply cutting and pasting one's way through life is useless. Your notes may temporarily serve you, but unless you apply judgement and reason to them to create something new, they will remain a scrapheap for future generations who will gain no wisdom or use from your efforts.

relate to: notes about notes being only useful to their creator

he kepthis note pads always in his pocket

The small size and portability of index cards make them easy to have at hand at a moment's notice.

He took it toWashington when he went into war service in 1917-1918;

Frederic Paxson took his note file from Wisconsin to Washington D.C. when he went into war service from 1917-1918, which Earl Pomeroy notes as an indicator of how little burden it was, but he doesn't make any notation about worries about loss or damage during travel, which may have potentially occurred to Paxson, given his practice and the value to him of the collection.

May be worth looking deeper into to see if he had such worries.

He had a separate bibliographical file,kept in six scantily filled drawers in his coat closet, and it is obvious

that he used it little in later years. His author-title entries usually went into the main file, after the appropriate subject index cards.

This is a curious pattern and not often seen. Apparently it was Paxson's practice to place his author-title entries into his main file following the related subject index cards instead of in a completely separate bibliographical file. He did apparently have one comprised of six scantily filled drawers which he kept in his coat closet, but it was little used in his later years.

What benefits might this relay? It certainly more directly relates the sources closer in physical proximity within one's collection to the notes to which they relate. This might be of particular beneficial use in a topical system where all of one's notes relating to a particular subject are close physically rather than being linked or cross referenced as they were in Luhmann's example.

A particular color of cards may help in this regard to more easily find these sources.

Also keep in mind that Paxson's system was topical-chronological, so there may also be reasons for doing this that fit into his chronological scheme. Was he filing them in sections so that the publication dates of the sources fit into this scheme as well? This may take direct review to better known and understand his practice.

While he didnot attempt to write down all that he thought and knew, apparentlyhe was seldom if ever at a loss to find a place for a note. He filedaway successive series of lecture notes, notes that he took on seminarreports, even notes on the scenery that he saw from a train.

notes on pretty much everything....

shows a more commonplace practice rather than just a zettelkasten focusing on his direct work.

November 7, 1916: "I expect to vote for Woodrow Wilson

I wonder if others use the sense making features of a note card system to think through their voting decisions? This seems an interesting and useful exercise which Paxson has done.

At all events notes on news-papers comprise the greater part of the Paxson note collection

s notes accumulated, hefiled them under new and subsidiary headings, with cross-references(on the index card) to related headings, which might be numerousand many years remote.

he three-by-five inch slipsof thin paper eventually filled about eighty wooden file drawers.And he classified the notes day by day, under topical-chronologicalheadings that eventually extended from 4639 B.C. to 1949, theyear after his death.

Frederic L. Paxson kept a collection of 3 x 5 " slips of thin paper that filled eighty wooden file drawers which he organized using topical-chronologic headings spanning 4639 BCE to 1949.

It is possible this Miscellany collection was assembled by Schutz as part of his own research as an historian, as well as the letters and documents collected as autographs for his interest as a collector;

https://catalog.huntington.org/record=b1792186

Is it possible that this miscellany collection is of a zettelkasten nature?

Found via a search of the Huntington Library for Frederic L. Paxson's zettelkasten

Turner was never comfortable at Harvard; when he retired in 1922 he became a visiting scholar at the Huntington Library in Los Angeles, where his note cards and files continued to accumulate, although few monographs got published. His The Frontier in American History (1920) was a collection of older essays.

Where did Turner's note cards and files end up? Are they housed at the Huntington Library? What other evidence or indication is there that this was an extensive zettelkasten practice here?

Thomas, Keith. “Diary: Working Methods.” London Review of Books, June 10, 2010. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v32/n11/keith-thomas/diary.

Historian Keith Thomas talks about his methods of note taking and work as a historian. A method which falls into the tradition of commonplacing and zettelkasten, though his was in note taking and excerpting onto slips which he kept in envelopes instead of notebooks or a card index.

When I go to libraries or archives, I make notes in a continuous form on sheets of paper, entering the page number and abbreviated title of the source opposite each excerpted passage. When I get home, I copy the bibliographical details of the works I have consulted into an alphabeticised index book, so that I can cite them in my footnotes. I then cut up each sheet with a pair of scissors. The resulting fragments are of varying size, depending on the length of the passage transcribed. These sliced-up pieces of paper pile up on the floor. Periodically, I file them away in old envelopes, devoting a separate envelope to each topic. Along with them go newspaper cuttings, lists of relevant books and articles yet to be read, and notes on anything else which might be helpful when it comes to thinking about the topic more analytically. If the notes on a particular topic are especially voluminous, I put them in a box file or a cardboard container or a drawer in a desk. I also keep an index of the topics on which I have an envelope or a file. The envelopes run into thousands.

Historian Keith Thomas describes his note taking method which is similar to older zettelkasten methods, though he uses larger sheets of paper rather than index cards and files them away in topic-based envelopes.

If a passage is interesting from several different points of view, then it should be copied out several times on different slips.

I don't recall Langlois and Seignobos suggesting copying things several times over. Double check this point, particularly with respect to the transference to Luhmann.

reply (unsent)<br /> I appreciate where you're coming from, and it's an excellent thought experiment. However, knowing that there was a clear older prior zettelkasten tradition for several hundred years prior to Luhmann which also included a number of mathematician practitioners including not only Leibnitz but also Newton, who incidentally invented his version of calculus in his waste book (also a part of that tradition). (See also: https://www.newtonproject.ox.ac.uk/texts/notebooks?sort=date&order=desc).

“To attain knowledge, add things everyday. To attain wisdom, remove things every day.” ― Lao Tse

original source??

now we need a much needed and truer history of zetelcaston and thankfully Chris aldricks is the person to provide us that

We need a much needed and truer history of zettelkasten and thankfully Chris Aldrich is the person to provide us that. Stop reading all those other zettelkasten articles until you have a broader understanding of the historical perspective of where all this came from. I can't tell you how much I learned. There was more I didn't know than I did know by a... and it wasn't even close. So thank you Chris. You definitely need to read The Two Definitions of Zettelkasten.<br /> —Nick Milo, Linking Your Thinking, 2022-10-26,

Chavigny, Paul Marie Victor. Organisation Du Travail Intellectuel, Recettes Pratiques à l’usage Des Étudiants de Toutes Les Facultés et de Tous Les Travailleurs. Paris: Delagrave, 1918. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011209555

http://drummer.this.how/AndySylvester99/Andy_Zettelkasten.opml

Andy Sylvester's experiment in building a digital zettelkasten using OPML and tagging. Curious to see how it grows and particularly whether or not it will scale with this sort of UI? On first blush, the first issue I see as a reader is a need for a stronger and immediate form of search.

RSS feeds out should make for a more interesting UI for subscribing and watching the inputs though.

The question often asked: "What happens when you want to add a new note between notes 1/1 and 1/1a?"

I've seen variations of the beginner Zettelkasten question:

"What happens when you want to add a new note between notes 1/1 and 1/1a?"

asked at least a dozen times in the Reddit fora related to note taking and zettelkasten, on zettelkasten.de, or in other places across the web.

From a mathematical perspective, these numbering or alpha-numeric systems are, by both intent and design, underpinned by the mathematical idea of dense sets. In the areas of topology and real analysis, one considers a set dense when one can choose a point as close as one likes to any other point. For both library cataloging systems and numbering schemes for ideas in Zettelkasten this means that you can always juxtapose one topic or idea in between any other two.

Part of the beauty of Melvil Dewey's original Dewey Decimal System is that regardless of how many new topics and subtopics one wants to add to their system, one can always fit another new topic between existing ones ad infinitum.

Going back to the motivating question above, the equivalent question mathematically is "what number is between 0.11 and 0.111?" (Here we've converted the artificial "number" "a" to a 1 and removed the punctuation, which doesn't create any issues and may help clarify the orderings a bit.) The answer is that there is an infinite number of numbers between these!

This is much more explicit by writing these numbers as:<br /> 0.110<br /> 0.111

Naturally 0.1101 is between them (along with an infinity of others), so one could start here as a means of inserting ideas this way if they liked. One either needs to count up sequentially (0, 1, 2, 3, ...) or add additional place values.

The problem most people face is that they're not thinking of these numbers as decimals, but as natural numbers or integers (or broadly numbers without any decimal portions). Though of course in the realm of real numbers, numbers above 0 are dense as well, but require the use of their decimal portions to remain so.

The tough question is: what sorts of semantic meanings one might attach to their adding of additional place values or their alphabetical characters? This meaning can vary from person to person and system to system, so I won't delve into it here.

One may find it useful to logically chunk these numbers into groups of three as is often done using commas, periods, slashes, dashes, spaces, or other punctuation. This doesn't need to mean anything in particular, but may help to make one's numbers more easily readable as well as usable for filing new ideas. Sometimes these indicators can be confusing in discussion, so if ever in doubt, simply remove them and the general principles mentioned here should still hold.

Depending on one's note taking system, however, when putting cards into some semblance of a logical sort-able order (perhaps within a folder for example), the system may choke on additional characters beyond the standard period to designate a decimal number. For example: within Obsidian, if you have a "zettelkasten" folder with lots of numbered and named files within it, you'll want to give each number the maximum number of decimal places so that when doing an alphabetic sort within the folder, all of the numbered ideas are properly sorted. As an example if you give one file the name "0.510 Mathematics", another "0.514 Topology" and a third "0.5141 Dense Sets" they may not sort properly unless you give the first two decimal expansions to the ten-thousands place at a minimum. If you changed them to "0.5100 Mathematics" and "0.5140 Topology, then you're in good shape and the folder will alphabetically sort as you'd expect. Similarly some systems may or may not do well with including alphabetic characters mixed in with numbers.

If using chunked groups of three numbers, one might consider using the number 0.110.001 as the next level of idea between them and then continuing from there. This may help to spread some of the ideas out as surely one may have yet another idea to wedge in between 0.110.000 and 0.110.001?

One can naturally choose almost any any (decimal) number, so long as it it somewhat "near" the original behind which one places it. By going out further in the decimal expansion, one can always place any idea between two others and know that there will be a number that it can be given that will "work".

Generally within numbers as we use them for mathematics, 0.100000001 is technically "closer" by distance measurement to 0.1 than 0.11, (and by quite a bit!) but somehow when using numbers for zettelkasten purposes, we tend to want to not consider them as decimals, as the Dewey Decimal System does. We also have the tendency to want to keep our numbers as short as possible when writing, so it seems more "natural" to follow 0.11 with 0.111, as it seems like we're "counting up" rather than "counting down".

Another subtlety that one sees in numbering systems is the proper or improper use of the whole numbers in front of the decimal portions. For example, in Niklas Luhmann's system, he has a section of cards that start with 3.XXXX which are close to a section numbered 35.YYYY. This may seem a bit confusing, but he's doing a bit of mental gymnastics to artificially keep his numbers smaller. What he really means is 3000.XXX and 3500.YYY respectively, he's just truncating the extra zeros. Alternately in a fully "decimal system" one would write these as 0.3000.XXXX and 0.3500.YYYY, where we've added additional periods to the numbers to make them easier to read. Using our original example in an analog system, the user may have been using foreshortened indicators for their system and by writing 1/1a, they may have really meant something of the form 001.001/00a, but were making the number shorter in a logical manner (at least to them).

The close observer may have seen Scott Scheper adopt the slightly longer numbers in the thousands (like 3500.YYYY) as a means of remedying some of the numbering confusion many have when looking at Luhmann's system.

Those who build their systems on top of existing ones like the Dewey Decimal Classification, or the Universal Decimal Classification may wish to keep those broad categories with three to four decimal places at the start and then add their own idea number underneath those levels.

As an example, we can use the numbering for Finsler geometry from the Dewey Decimal Classification wikipedia page shown as:

``` 500 Natural sciences and mathematics

510 Mathematics

516 Geometry

516.3 Analytic geometries

516.37 Metric differential geometries

516.375 Finsler geometry

```

So in our zettelkasten, we might add our first card on the topic of Finsler geometry as "516.375.001 Definition of Finsler geometry" and continue from there with some interesting theorems and proofs on those topics.

Of course, while this is something one can do doesn't mean that one should do it. Going too far down the rabbit holes of "official" forms of classification this way can be a massive time wasting exercise as in most private systems, you're never going to be comparing your individual ideas with the private zettelkasten of others and in practice the sort of standardizing work for classification this way is utterly useless. Beyond this, most personal zettelkasten are unique and idiosyncratic to the user, so for example, my math section labeled 510 may have a lot more overlap with history, anthropology, and sociology hiding within it compared with others who may have all of their mathematics hiding amidst their social sciences section starting with the number 300. One of the benefits of Luhmann's numbering scheme, at least for him, is that it allowed his system to be much more interdisciplinary than using a more complicated Dewey Decimal oriented system which may have dictated moving some of his systems theory work out of his politics area where it may have made more sense to him in addition to being more productive on a personal level.

Of course if you're using the older sort of commonplacing zettelkasten system that was widely in use before Luhmann's variation, then perhaps using a Dewey-based system may be helpful to you?

As both a mathematician working in the early days of real analysis and a librarian, some of these loose ideas may have occurred tangentially to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646 - 1716), though I'm currently unaware of any specific instances within his work. One must note, however, that some of the earliest work within library card catalogs as we know and use them today stemmed from 1770s Austria where governmental conscription needs overlapped with card cataloging systems (Krajewski, 2011). It's here that the beginnings of these sorts of numbering systems begin to come into use well before Melvil Dewey's later work which became much more broadly adopted.

The German "file number" (aktenzeichen) is a unique identification of a file, commonly used in their court system and predecessors as well as file numbers in public administration since at least 1934. We know Niklas Luhmann studied law at the University of Freiburg from 1946 to 1949, when he obtained a law degree, before beginning a career in Lüneburg's public administration where he stayed in civil service until 1962. Given this fact, it's very likely that Luhmann had in-depth experience with these sorts of file numbers as location identifiers for files and documents. As a result it's reasonably likely that a simplified version of these were at least part of the inspiration for his own numbering system. † ‡

At the end of the day, the numbering system you choose needs to work for you within the system you're using (analog, digital, other). I would generally recommend against using someone else's numbering system unless it completely makes sense to you and you're able to quickly and simply add cards to your system with out the extra work and cognitive dissonance about what number you should give it. The more you simplify these small things, the easier and happier you'll be with your set up in the end.

Krajewski, Markus. Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548-1929. Translated by Peter Krapp. History and Foundations of Information Science. MIT Press, 2011. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/paper-machines.

Munkres, James R. Topology. 2nd ed. 1975. Reprint, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1999.

Much like the way the Obsidian journal plugin counts words within one's daily journal page, this app counts zettels within a folder to help encourage one to maintain some level of output.

https://ead.nb.admin.ch/html/comment_0.html

The layout and format of this online archive is highly reminiscent of a digital zettelkasten and could even be used as a user interface for implementing one. It has a nice alpha-numeric form.

Handwriting + Zettelkasten

I've used Livescribe pens/paper for note taking (including with audio) before, and they've got OCR software to digital workflows. Or for the paper motivated, one could use their larger post it notes and just stick them to index cards as a substrate for your physical ZK with digitally searchable back ups? Now that I've thought about it and written this out, I may have to try it to see if it's better than my prior handwritten/digital experiments.

CardNotes - Zettelkasten Notes 4+ Linkable Handwritten Notes HANG FONG TSE

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/cardnotes-zettelkasten-notes/id1611515089

TweetSee new TweetsConversationSamuele Onelia @SamueleOneliaI added a new note to my #Zettelkasten after a month of inactivity. It still remains my favorite kind of mental therapy.

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>I added a new note to my #Zettelkasten after a month of inactivity.<br><br>It still remains my favorite kind of mental therapy. <br><br>BTW this is the note (from the book: Effortless) 👇 pic.twitter.com/QF2Uy3W3T6

— Samuele Onelia 😺 (@SamueleOnelia) October 24, 2022

One of W.G. Sebald’s masterpieces, The Rings of Saturn, an indescribable blend of fact and fiction, contains a section about one of his academic colleagues whose office was piled high with notes about Gustav Flaubert.

https://twitter.com/friendsofdarwin/status/1584936047929982976

What would you suggest instead if my goal is taking notes on various topics in order to remember them? (no output needed)

reply to dhXcol https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/yc35nl/comment/itlmjbn/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

You might appreciate the pre-Luhmann zettelkasten (or commonplace book traditions) which could serve this purpose, and most of the applications that you can use for ZK will work for these purposes if you're not an index card person. Some differentiation and pointers here: https://boffosocko.com/2022/10/22/the-two-definitions-of-zettelkasten/

Les murs du cabinet de travail, le plancher, le plafond même portaient des liasses débordantes, des cartons démesurément gonflés, des boîtes où se pressait une multitude innombrable de fiches, et je contemplai avec une admiration mêlée de terreur les cataractes de l'érudition prêtes à se rompre. —Maître, fis-je d'une voix émue, j'ai recours à votre bonté et à votre savoir, tous deux inépuisables. Ne consentiriez-vous pas à me guider dans mes recherches ardues sur les origines de l'art pingouin? —Monsieur, me répondit le maître, je possède tout l'art, vous m'entendez, tout l'art sur fiches classées alphabétiquement et par ordre de matières. Je me fais un devoir de mettre à votre disposition ce qui s'y rapporte aux Pingouins. Montez à cette échelle et tirez cette boîte que vous voyez là-haut. Vous y trouverez tout ce dont vous avez besoin. J'obéis en tremblant. Mais à peine avais-je ouvert la fatale boîte que des fiches bleues s'en échappèrent et, glissant entre mes doigts, commencèrent à pleuvoir. Presque aussitôt, par sympathie, les boîtes voisines s'ouvrirent et il en coula des ruisseaux de fiches roses, vertes et blanches, et de proche en proche, de toutes les boîtes les fiches diversement colorées se répandirent en murmurant comme, en avril, les cascades sur le flanc des montagnes. En une minute elles couvrirent le plancher d'une couche épaisse de papier. Jaillissant de leurs inépuisables réservoirs avec un mugissement sans cesse grossi, elles précipitaient de seconde en seconde leur chute torrentielle. Baigné jusqu'aux genoux, Fulgence Tapir, d'un nez attentif, observait le cataclysme; il en reconnut la cause et pâlit d'épouvante. —Que d'art! s'écria-t-il. Je l'appelai, je me penchai pour l'aider à gravir l'échelle qui pliait sous l'averse. Il était trop tard. Maintenant, accablé, désespéré, lamentable, ayant perdu sa calotte de velours et ses lunettes d'or, il opposait en vain ses bras courts au flot qui lui montait jusqu'aux aisselles. Soudain une trombe effroyable de fiches s'éleva, l'enveloppant d'un tourbillon gigantesque. Je vis durant l'espace d'une seconde dans le gouffre le crâne poli du savant et ses petites mains grasses, puis l'abîme se referma, et le déluge se répandit sur le silence et l'immobilité. Menacé moi-même d'être englouti avec mon échelle, je m'enfuis à travers le plus haut carreau de la croisée.

France, Anatole. L’Île Des Pingouins. Project Gutenberg 8524. 1908. Reprint, Project Gutenberg, 2005. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/8524/pg8524.html

In the preface to the novel Penguin Island (L'Île des Pingouins. Calmann-Lévy, 1908) by Nobel prize laureate Anatole France, a scholar is drowned by an avalanche of index cards which formed a gigantic whirlpool streaming out of his card index (Zettelkasten).

Link to: Historian Keith Thomas has indicated that he finds it hard to take using index cards for excerpting and research seriously as a result of reading this passage in the satire Penguin Island.<br /> https://hypothes.is/a/rKAvtlQCEe2jtzP3LmPlsA

Translation via: France, Anatole. Penguin Island. Translated by Arthur William Evans. 8th ed. 1908. Reprint, New York, NY, USA: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1922. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Penguin_Island/6UpWAvkPQaEC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Small changes in the translation by me, comprising only adding the word "index" in front of the occurrences of card to better represent the historical idea of fiches used by scholars in the late 1800s and early 1900s, are indicated in brackets.

The walls of the study, the floor, and even the ceiling were loaded with overflowing bundles, paste board boxes swollen beyond measure, boxes in which were compressed an innumerable multitude of small [index] cards covered with writing. I beheld in admiration mingled with terror the cataracts of erudition that threatened to burst forth.

“Master,” said I in feeling tones, “I throw myself upon your kindness and your knowledge, both of which are inexhaustible. Would you consent to guide me in my arduous researches into the origins of Penguin art?"

“Sir," answered the Master, “I possess all art, you understand me, all art, on [index] cards classed alphabetically and in order of subjects. I consider it my duty to place at your disposal all that relates to the Penguins. Get on that ladder and take out that box you see above. You will find in it everything you require.”

I tremblingly obeyed. But scarcely had I opened the fatal box than some blue [index] cards escaped from it, and slipping through my fingers, began to rain down.

Almost immediately, acting in sympathy, the neighbouring boxes opened, and there flowed streams of pink, green, and white [index] cards, and by degrees, from all the boxes, differently coloured [index] cards were poured out murmuring like a waterfall on a mountain-side in April. In a minute they covered the floor with a thick layer of paper. Issuing from their in exhaustible reservoirs with a roar that continually grew in force, each second increased the vehemence of their torrential fall. Swamped up to the knees in cards, Fulgence Tapir observed the cataclysm with attentive nose. He recognised its cause and grew pale with fright.

“ What a mass of art! ” he exclaimed.

I called to him and leaned forward to help him mount the ladder which bent under the shower. It was too late. Overwhelmed, desperate, pitiable, his velvet smoking-cap and his gold-mounted spectacles having fallen from him, he vainly opposed his short arms to the flood which had now mounted to his arm-pits . Suddenly a terrible spurt of [index] cards arose and enveloped him in a gigantic whirlpool. During the space of a second I could see in the gulf the shining skull and little fat hands of the scholar; then it closed up and the deluge kept on pouring over what was silence and immobility. In dread lest I in my turn should be swallowed up ladder and all I made my escape through the topmost pane of the window.

Zettelkasten in the office of Clement Atlee, former Prime Minister of UK, in The Crown S1E4 "Act of God" (Netflix, 2016)

https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/ur5xjv/handwritten_cards_to_a_digital_back_up_workflow/

For those who keep a physical pen and paper system who either want to be a bit on the hybrid side, or just have a digital backup "just in case", I thought I'd share a workflow that I outlined back in December that works reasonably well. (Backups or emergency plans for one's notes are important as evidenced by poet Jean Paul's admonition to his wife before setting off on a trip in 1812: "In the event of a fire, the black-bound excerpts are to be saved first.") It's framed as posting to a website/digital garden, but it works just as well for many of the digital text platforms one might have or consider. For those on other platforms (like iOS) there are some useful suggestions in the comments section. Handwriting My Website (or Zettelkasten) with a Digital Amanuensis

https://www.denizcemonduygu.com/philo/browse/