To a great extent, Hypothes.is has such a small footprint of users (in comparison to massive platforms like Twitter, Facebook, etc.) that it's never been a performative platform for me. As a design choice they have specifically kept their social media functionalities very sparse, so one also doesn't generally encounter the toxic elements that are rampant in other locations. This helps immensely. I might likely change my tune if it were ever to hit larger scales or experienced the Eternal September effect.

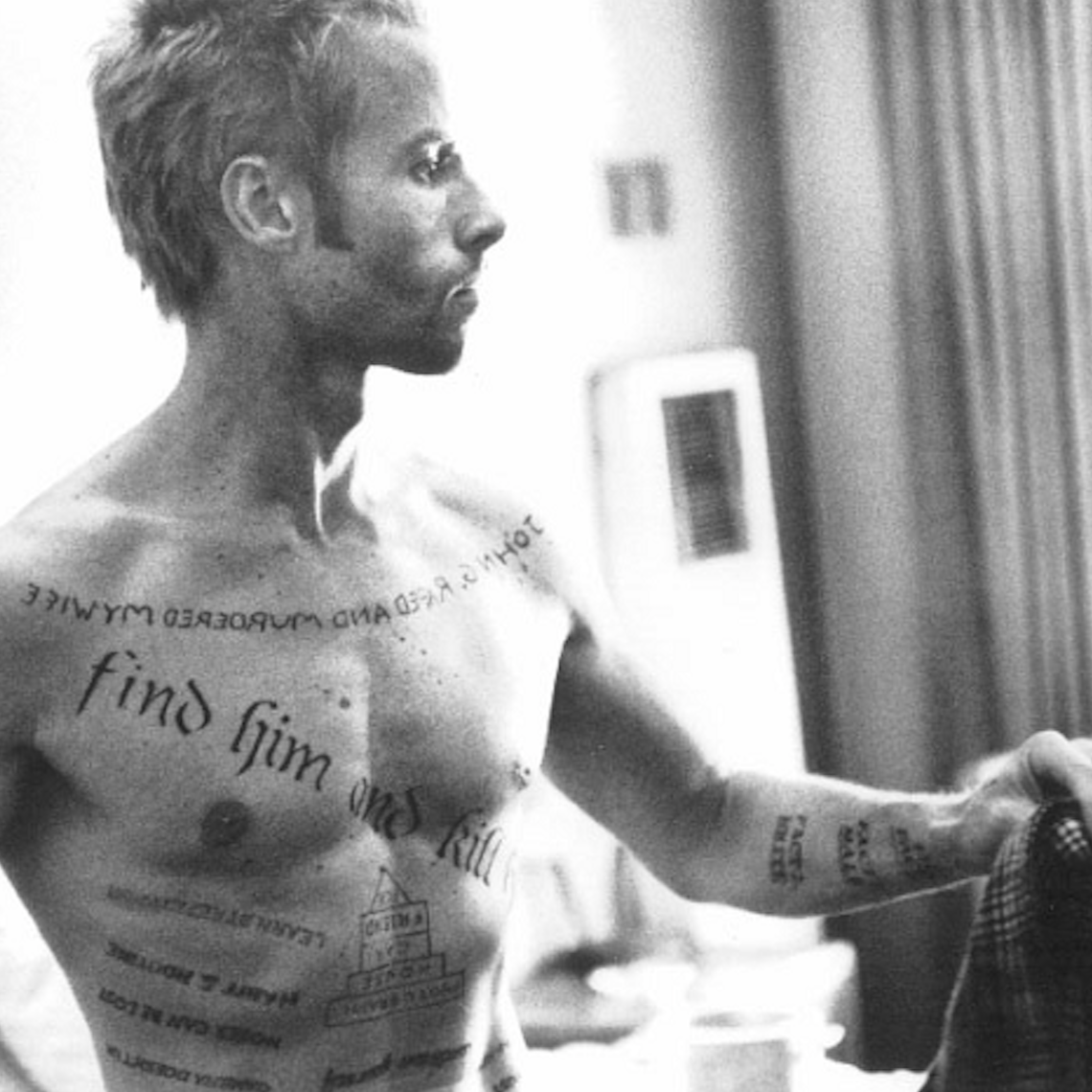

Beyond this, I mostly endeavor to write things for later re-use. As a result I'm trying to write as clearly as possible in full sentences and explain things as best I can so that my future self doesn't need to do heavy work or lifting to recreate the context or do heavy editing. Writing notes in public and knowing that others might read these ideas does hold my feet to the fire in this respect. Half-formed thoughts are often shaky and unclear both to me and to others and really do no one any good. In personal experience they also tend not to be revisited and revised or revised as well as I would have done the first time around (in public or otherwise).

Occasionally I'll be in a rush reading something and not have time for more detailed notes in which case I'll do my best to get the broad gist knowing that later in the day or at least within the week, I'll revisit the notes in my own spaces and heavily elaborate on them. I've been endeavoring to stay away from this bad habit though as it's just kicking the can down the road and not getting the work done that I ultimately want to have. Usually when I'm being fast/lazy, my notes will revert to highlighting and tagging sections of material that are straightforward facts that I'll only be reframing into my own words at a later date for reuse. If it's an original though or comment or link to something important, I'll go all in and put in the actual work right now. Doing it later has generally been a recipe for disaster in my experience.

There have been a few instances where a half-formed thought does get seen and called out. Or it's a thought which I have significantly more personal context for and that is only reflected in the body of my other notes, but isn't apparent in the public version. Usually these provide some additional insight which I hadn't had that makes the overall enterprise more interesting. Here's a recent example, albeit on a private document, but which I think still has enough context to be reasonably clear: https://hypothes.is/a/vmmw4KPmEeyvf7NWphRiMw

There may also be infrequent articles online which are heavily annotated and which I'm excerpting ideas to be reused later. In these cases I may highlight and rewrite them in my own words for later use in a piece, but I'll make them private or put them in a private group as they don't add any value to the original article or potential conversation though they do add significant value to my collection as "literature notes" for immediate reuse somewhere in the future. On broadly unannotated documents, I'll leave these literature notes public as a means of modeling the practice for others, though without the suggestion of how they would be (re-)used for.

All this being said, I will very rarely annotate things privately or in a private group if they're of a very sensitive cultural nature or personal in manner. My current set up with Hypothesidian still allows me to import these notes into Obsidian with my API key. In practice these tend to be incredibly rare for me and may only occur a handful of times in a year.

Generally my intention is that ultimately all of my notes get published in something in a final form somewhere, so I'm really only frontloading the work into the notes now to make the writing/editing process easier later.

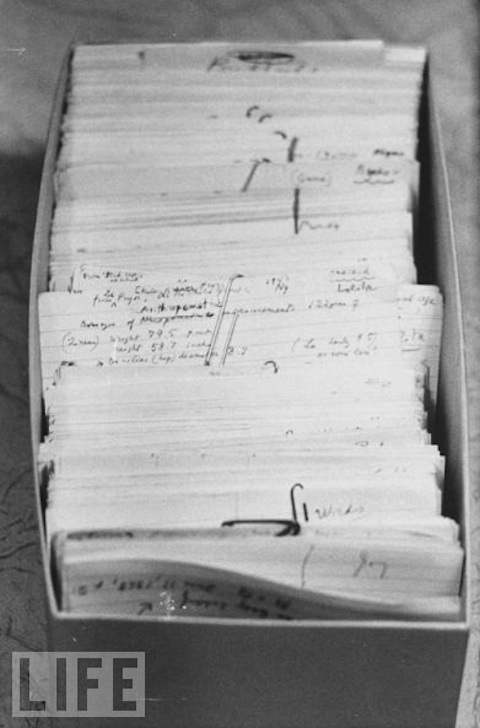

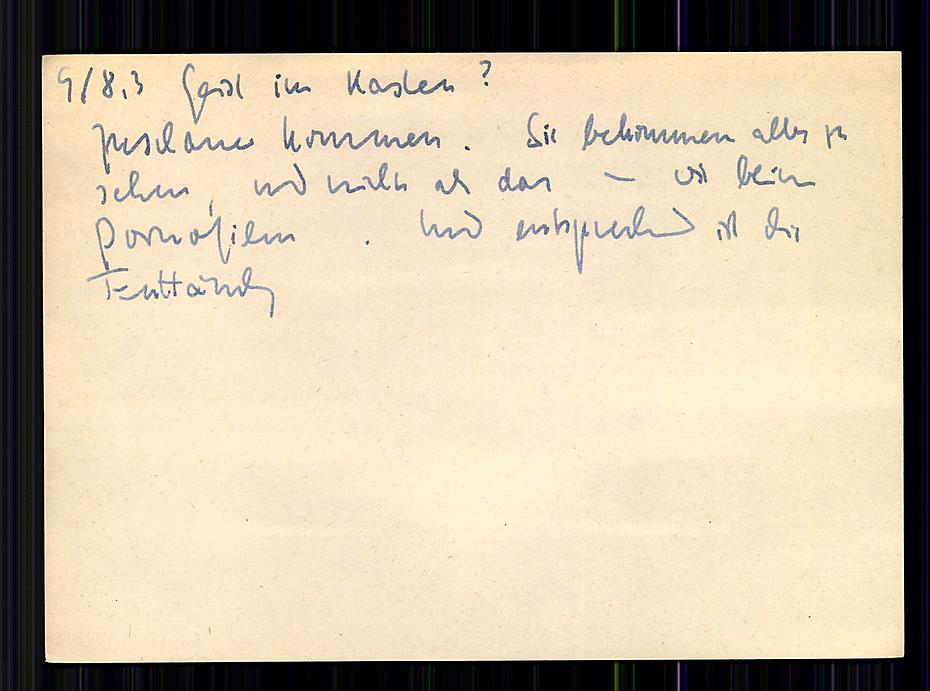

Niklas Luhmann, Zettelkasten II,

Niklas Luhmann, Zettelkasten II,