Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Authors’ reply (____Ono et al)

Review Commons Refereed Preprint #RC-2025-03137

Reviewer #1 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

Ono et al addressed how condensin II and cohesin work to define chromosome territories (CT) in human cells. They used FISH to assess the status of CT. They found that condensin II depletion leads to lengthwise elongation of G1 chromosomes, while double depletion of condensin II and cohesin leads to CT overlap and morphological defects. Although the requirement of condensin II in shortening G1 chromosomes was already shown by Hoencamp et al 2021, the cooperation between condensin II and cohesin in CT regulation is a new finding. They also demonstrated that cohesin and condensin II are involved in G2 chromosome regulation on a smaller and larger scale, respectively. Though such roles in cohesin might be predictable from its roles in organizing TADs, it is a new finding that the two work on a different scale on G2 chromosomes. Overall, this is technically solid work, which reports new findings about how condensin II and cohesin cooperate in organizing G1 and G2 chromosomes.

We greatly appreciate the reviewer’s supportive comments. The reviewer has accurately recognized our new findings concerning the collaborative roles of condensin II and cohesin in establishing and maintaining interphase chromosome territories.

Major point:

They propose a functional 'handover' from condensin II to cohesin, for the organization of CTs at the M-to-G1 transition. However, the 'handover', i.e. difference in timing of executing their functions, was not experimentally substantiated. Ideally, they can deplete condensin II and cohesin at different times to prove the 'handover'. However, this would require the use of two different degron tags and go beyond the revision of this manuscript. At least, based on the literature, the authors should discuss why they think condensin II and cohesin should work at different timings in the CT organization.

We take this comment seriously, especially because Reviewer #2 also expressed the same concern.

First of all, we must admit that the basic information underlying the “handover” idea was insufficiently explained in the original manuscript. Let us make it clear below:

- Condensin II bound to chromosomes and is enriched along their axes from anaphase through telophase (Ono et al., 2004; Hirota et al., 2004; Walther et al., 2018).

- In early G1, condensin II is diffusely distributed within the nucleus and does not bind tightly to chromatin, as shown by detergent extraction experiments (Ono et al., 2013).

- Cohesin starts binding to chromatin when the cell nucleus reassembles (i.e., during the cytokinesis stage shown in Fig. 1B), apparently replacing condensins I and II (Brunner et al., 2025).

- Condensin II progressively rebinds to chromatin from S through G2 phase (Ono et al., 2013).

The cell cycle-dependent changes in chromosome-bound condensin II and cohesin summarized above are illustrated in Fig. 1A. We now realize that Fig. 1B in the original manuscript was inconsistent with Fig. 1A, creating unnecessary confusion, and we sincerely apologize for this. The fluorescence images shown in the original Fig. 1B were captured without detergent extraction prior to fixation, giving the misleading impression that condensin II remained bound to chromatin from cytokinesis through early G1. This was not our intention. To clarify this, we have repeated the experiment in the presence of detergent extraction and replaced the original Fig. 1B with a revised panel. Figs. 1A and 1B are now more consistent with each other. Accordingly, we have modified the correspsonding sentences as follows:

Although condensin II remains nuclear throughout interphase, its chromatin binding is weak in G1 and becomes robust from S phase through G2 (Ono et al., 2013). Cohesin, in contrast, replaces condensin II in early G1 (Fig. 1 B)(Abramo et al., 2019; Brunner et al., 2025), and establishes topologically associating domains (TADs) in the G1 nucleus (Schwarzer et al., 2017; Wutz et al., 2017)*. *

While there is a loose consensus in the field that condensin II is replaced by cohesin during the M-to-G1 transition, it remains controversial whether there is a short window during which neither condensin II nor cohesin binds to chromatin (Abramo et al., 2019), or whether there is a stage in which the two SMC protein complexes “co-occupy” chromatin (Brunner et al., 2025). Our images shown in the revised Fig. 1B cannot clearly distinguish between these two possibilities.

From a functional point of view, the results of our depletion experiments are more readily explained by the latter possibility. If this is the case, the “interplay” or “cooperation” rather than the “handover” may be a more appropriate term to describe the functional collaboration between condensin II and cohesin during the M-to-G1 transition. For this reason, we have avoided the use of the word “handover” in the revised manuscript. It should be emphasized, however, that given their distinct chromosome-binding kinetics, the cooperation of the two SMC complexes during the M-to-G1 transition is qualitatively different from that observed in G2. Therefore, the central conclusion of the present study remains unchanged.

For example, a sentence in Abstract has been changed as follows:

a functional interplay between condensin II and cohesin during the mitosis-to-G1 transition is critical for establishing chromosome territories (CTs) in the newly assembling nucleus.

While the reviewer suggested one experiment, it is clearly beyond the scope of the current study. It should also be noted that even if such a cell line were available, the proposed application of sequential depletion to cells progressing from mitosis to G1 phase would be technically challenging and unlikely to produce results that could be interpreted with confidence.

Other points:

Figure 2E: It seems that the chromosome length without IAA is shorter in Rad21-aid cells than H2-aid cells or H2-aid Rad21-aid cells. How can this be interpreted?

This comment is well taken. A related comment was made by Reviewer #3 (Major comment #2). Given the substantial genetic manipulations applied to establish multiple cell lines used in the present study, it is, strictly speaking, not straightforward to compare the -IAA controls between different cell lines. Such variations are most prominently observed in Fig. 2E, although they can also be observed to lesser extent in other experiments (e.g., Fig. 3E). This issue is inherently associated with all studies using genetically manipulated cell lines and therefore cannot be completely avoided. For this reason, we focus on the differences between -IAA and +IAA within each cell line, rather than comparing the -IAA conditions across different cell lines. In this sense, a sentence in the original manuscript (lines 178-180) was misleading. In the revised manuscript, we have modified the corresponding and subsequent sentence as follows:

Although cohesin depletion had a marginal effect on the distance between the two site-specific probes (Fig.2, C and E), double depletion did not result in a significant change (Fig.2, D and E), consistent with the partial restoration of centromere dispersion (Fig. 1G).

In addition, we have added a section entitled “Limitations of the study” at the end of the Discussion to address technical issues that are inevitably associated with the current approach.

Figure 3: Regarding the CT morphology, could they explain further the difference between 'elongated' and 'cloud-like (expanded)'? Is it possible to quantify the frequency of these morphologies?

In the original manuscript, we provided data that quantitatively distinguished between the “elongated” and “cloud-like” phenotypes. Specifically, Fig. 2E shows that the distance between two specific loci (Cen 12 and 12q15) is increased in the elongated phenotype but not in the cloud-like phenotype. In addition, the cloud-like morphology was clearly deviated from circularity, as indicated by the circularity index (Fig. 3F). However, because circularity can also decrease in rod-shaped chromosomes, these datasets alone may not be sufficiently convincing, as the reviewer pointed out. We have now included an additional parameter, the aspect ratio, defined as the ratio of an object’s major axis to its minor axis (new Fig. 3F). While this intuitive parameter was altered upon condensin II depletion and double depletion, again, we acknowledge that it is not sufficient to convincingly distinguish between the elongated and cloud-like phenotypes proposed in the original manuscript. For these reasons, in the revised manuscript, we have toned down our statements regarding the differences in CT morphology between the two conditions. Nonetheless, together with the data from Figs. 1 and 2, it is that the Rabl configuration observed upon condensin II depletion is further exacerbated in the absence of cohesin. Accordingly, we have modified the main text and the cartoon (Fig 3H) to more accurately depict the observations summarized above.

Figure 5: How did they assign C, P and D3 for two chromosomes? The assignment seems obvious in some cases, but not in other cases (e.g. in the image of H2-AID#2 +IAA, two D3s can be connected to two Ps in the other way). They may have avoided line crossing between two C-P-D3 assignments, but can this be justified when the CT might be disorganized e.g. by condensin II depletion?

This comment is well taken. As the reviewer suspected, we avoided line crossing between two sets of assignments. Whenever there was ambiguity, such images were excluded from the analysis. Because most chromosome territories derived from two homologous chromosomes are well separated even under the depleted conditions as shown in Fig. 6C, we did not encounter major difficulties in making assignments based on the criteria described above. We therefore remain confident that our conclusion is valid.

That said, we acknowledge that our assignments of the FISH images may not be entirely objective. We have added this point to the “Limitations of the study” section at the end of the Discussion.

Figure 6F: The mean is not indicated on the right-hand side graph, in contrast to other similar graphs. Is this an error?

We apologize for having caused this confusion. First, we would like to clarify that the right panel of Fig. 6F should be interpreted together with the left panel, unlike the seemingly similar plots shown in Figs. 6G and 6H. In the left panel of Fig. 6F, the percentages of CTs that contact the nucleolus are shown in grey, whereas those that do not are shown in white. All CTs classified in the “non-contact” population (white) have a value of zero in the right panel, represented by the bars at 0 (i.e., each bar corresponds to a collection of dots having a zero value). In contrast, each CT in the “contact” population (grey) has a unique contact ratio value in the right panel. Because the right panel consists of two distinct groups, we reasoned that placing mean or median bars would not be appropriate. This was why no mean or median bars were shown in in the tight panel (The same is true for Fig. S5 A and B).

That said, for the reviewer’s reference, we have placed median bars in the right panel (see below). In the six cases of H2#2 (-/+IAA), Rad21#2 (-/+IAA), Double#2 (-IAA), and Double#3 (-IAA), the median bars are located at zero (note that in these cases the mean bars [black] completely overlap with the “bars” derived from the data points [blue and magenta]). In the two cases of Double#2 (+IAA) and Double#3 (+IAA), they are placed at values of ~0.15. Statistically significant differences between -IAA and +IAA are observed only in Double#2 and Double#3, as indicated by the P-value shown on the top of the panel. Thus, we are confident in our conclusion that CTs undergo severe deformation in the absence of both condensin II and cohesin.

Figure S1A: The two FACS profiles for Double-AID #3 Release-2 may be mixed up between -IAA and +IAA.

The review is right. This inadvertent error has been corrected.

The method section explains that 'circularity' shows 'how closely the shape of an object approximates a perfect circle (with a value of 1 indicating a perfect circle), calculated from the segmented regions'. It would be helpful to provide further methodological details about it.

We have added further explanations regarding the circularity in Materials and Methods together with a citation (two added sentences are underlined below):

To analyze the morphology of nuclei, CTs, and nucleoli, we measured “circularity,” a morphological index that quantifies how closely the shape of an object approximates a perfect circle (value =1). Circularity was defined as 4π x Area/Perimeter2, where both the area and perimeter of each segmented object were obtained using ImageJ. This index ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 representing more circular objects and lower values correspond to elongated or irregular shapes (Chen et al, 2017).

Chen, B., Y. Wang, S. Berretta and O. Ghita. 2017. Poly Aryl Ether Ketones (PAEKs) and carbon-reinforced PAEK powders for laser sintering. J Mater Sci 52:6004-6019.

Reviewer #1 (Significance (Required)):

Ono et al addressed how condensin II and cohesin work to define chromosome territories (CT) in human cells. They used FISH to assess the status of CT. They found that condensin II depletion leads to lengthwise elongation of G1 chromosomes, while double depletion of condensin II and cohesin leads to CT overlap and morphological defects. Although the requirement of condensin II in shortening G1 chromosomes was already shown by Hoencamp et al 2021, the cooperation between condensin II and cohesin in CT regulation is a new finding. They also demonstrated that cohesin and condensin II are involved in G2 chromosome regulation on a smaller and larger scale, respectively. Though such roles in cohesin might be predictable from its roles in organizing TADs, it is a new finding that the two work on a different scale on G2 chromosomes. Overall, this is technically solid work, which reports new findings about how condensin II and cohesin cooperate in organizing G1 and G2 chromosomes.

See our reply above.

Reviewer #2 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

Summary:

Ono et al use a variety of imaging and genetic (AID) depletion approaches to examine the roles of condensin II and cohesin in the reformation of interphase genome architecture in human HCT16 cells. Consistent with previous literature, they find that condensin II is required for CENP-A dispersion in late mitosis/early G1. Using in situ FISH at the centromere/q arm of chromosome 12 they then establish that condensin II removal causes lengthwise elongation of chromosomes that, interestingly, can be suppressed by cohesin removal. To better understand changes in whole-chromosome morphology, they then use whole chromosome painting to examine chromosomes 18 and 19. In the absence of condensin II, cells effectively fail to reorganise their chromosomes from rod-like structures into spherical chromosome territories (which may explain why CENP-A dispersion is suppressed). Cohesin is not required for spherical CT formation, suggesting condensin II is the major initial driver of interphase genome structure. Double depletion results in complete disorganisation of chromatin, leading the authors to conclude that a typical cell cycle requires orderly 'handover' from the mitotic to interphase genome organising machinery. The authors then move on to G2 phase, where they use a variety of different FISH probes to assess alterations in chromosome structure at different scales. They thereby establish that perturbation of cohesin or condensin II influences local and longer range chromosome structure, respectively. The effects of condensin II depletion become apparent at a genomic distance of 20 Mb, but are negligible either below or above. The authors repeat the G1 depletion experiment in G2 and now find that condensin II and cohesin are individually dispensable for CT organisation, but that dual depletion causes CT collapse. This rather implies that there is cooperation rather than handover per se. Overall this study is a broadly informative multiscale investigation of the roles of SMC complexes in organising the genome of postmitotic cells, and solidifies a potential relationship between condensin II and cohesin in coordinating interphase genome structure. The deeper investigation of the roles of condensin II in establishing chromosome territories and intermediate range chromosome structure in particular is a valuable and important contribution, especially given our incomplete understanding of what functions this complex performs during interphase.

We sincerely appreciate the reviewer’s supportive comments. The reviewer has correctly acknowledged both the current gaps in our understanding of the role of condensin II in interphase chromosome organization and our new findings on the collaborative roles of condensin II and cohesin in establishing and maintaining interphase chromosome territories.

Major comments:

In general the claims and conclusions of the manuscript are well supported by multiscale FISH labelling. An important absent control is western blotting to confirm protein depletion levels. Currently only fluorescence is used as a readout for the efficiency of the AID depletion, and we know from prior literature that even small residual quantities of SMC complexes are quite effective in organising chromatin. I would consider a western blot a fairly straightforward and important technical control.

Let me explain why we used immunofluorescence measurements to evaluate the efficiency of depletion. In our current protocol for synchronizing at the M-to-G1 transition, ~60% of control and H2-depleted cells, and ~30% of Rad21-depleted and co-depleted cells, are successfully synchronized in G1 phase. The apparently lower synchronization efficiency in the latter two groups is attributable to the well-documented mitotic delay caused by cohesin depletion. From these synchronized populations, early G1 cells were selected based on their characteristic morphologies (see the legend of Fig. 1C). In this way, we analyzed an early G1 cell population that had completed mitosis without chromosome segregation defects. We acknowledge that this represents a technically challenging aspect of M-to-G1 synchronization in HCT116 cells, whose synchronization efficiency is limited compared with that of HeLa cells. Nevertheless, this approach constitutes the most practical strategy currently available. Hence, immunofluorescence provides the only feasible means to evaluate depletion efficiency under these conditions.

Although immunoblotting can, in principle, be applied to G2-arrested cell populations, we do not believe that information obtained from such experiments would affect the main conclusions of the current study. Please note that we carefully designed and performed all experiments with appropriate controls: H2 depletion, RAD21 depletion, and double depletion, with outcomes confirmed using independent cell lines (Double-AID#2 and Double-AID#3) whenever deemed necessary.

We fully acknowledge the technical limitations associated with the AID-mediated depletion techniques, which are now described in the section entitled “Limitations of the study” at the end of the Discussion. Nevertheless, we emphasize that these limitations do not compromise the validity of our findings.

I find the point on handover as a mechanism for maintaining CT architecture somewhat ambiguous, because the authors find that the dependence simply switches from condensin II to both condensin II and cohesin, between G1 and G2. To me this implies augmented cooperation rather than handover. I have two further suggestions, both of which I would strongly recommend but would consider desirable but 'optional' according to review commons guidelines.

First of all, we would like to clarify a possible misunderstanding regarding the phrase “handover as a mechanism for maintaining CT architecture somewhat ambiguous”. In the original manuscript, we proposed handover as a mechanism for establishing G1 chromosome territories, not for maintaining CTs.

That said, we take this comment very seriously, especially because Reviewer #1 also expressed the same concern. Please see our reply to Reviewer #1 (Major point).

In brief, we agree with the reviewer that the word “handover” may not be appropriate to describe the functional relationship between condensin II and cohesin during the M-to-G1 transition. In the revised manuscript, we have avoided the use of the word “handover”, replacing it with “interplay”. It should be emphasized, however, that given their distinct chromosome-binding kinetics, the cooperation of the two SMC complexes during the M-to-G1 transition is qualitatively different from that observed in G2. Therefore, the central conclusion of the present study remains unchanged.

For example, a sentence in Abstract has been changed as follows:

a functional interplay between condensin II and cohesin during the mitosis-to-G1 transition is critical for establishing chromosome territories (CTs) in the newly assembling nucleus.

Firstly, the depletions are performed at different stages of the cell cycle but have different outcomes. The authors suggest this is because handover is already complete, but an alternative possibility is that the phenotype is masked by other changes in chromosome structure (e.g. duplication/catenation). I would be very curious to see, for example, how the outcome of this experiment would change if the authors were to repeat the depletions in the presence of a topoisomerase II inhibitor.

The reviewer’s suggestion here is somewhat vague, and it is unclear to us what rationale underlies the proposed experiment or what meaningful outcomes could be anticipated. Does the reviewer suggest that we perform topo II inhibitor experiments both during the M-to-G1 transition and in G2 phase, and then compare the outcomes between the two conditions?

For the M-to-G1 transition, Hildebrand et at (2024) have already reported such experiments. They used a topo II inhibitor to provided evidence that mitotic chromatids are self-entangled and that the removal of these mitotic entanglements is required to establish a normal interphase nucleus. Our own preliminary experiments (not presented in the current manuscript) showed that ICRF treatment of cells undergoing the M-to-G1 transition did not affect post-mitotic centromere dispersion. The same treatment also had little effect on the suppression of centromere dispersion observed in condensin II-depleted cells.

Under G2-arrested condition, because chromosome territories are largely individualized, we would expect topo II inhibition to affect only the extent of sister catenation, which is not the focus of our current study. We anticipate that inhibiting topo II in G2 would have only a marginal, if any, effect on the maintenance of chromosome territories detectable by our current FISH approaches.

In any case, we consider the suggested experiment to be beyond the scope of the present manuscript, which focuses on the collaborative roles of condensin II and cohesin as revealed by multi-scale FISH analyses.

Secondly, if the author's claim of handover is correct then one (not exclusive) possibility is that there is a relationship between condensin II and cohesin loading onto chromatin. There does seem to be a modest co-dependence (e.g. fig S4 and S7), could the authors comment on this?

First of all, we wish to point out the reviewer’s confusion between the G2 experiments and the M-to-G1 experiments. Figs. S4 and S7 concern experiments using G2-arrested cells, not M-to-G1 cells in which a possible handover mechanism is discussed. Based on Fig. 1, in which the extent of depletion in M-to-G1 cells was tested, no evidence of “co-dependence” between H2 depletion and RAD21 depletion was observed.

That said, as the reviewer correctly points out, we acknowledge the presence of marginal yet statistically significant reductions in the RAD21 signal upon H2 depletion (and vice versa) in G2-arrested cells (Figs. S4 and S7).

Another control experiment here would be to treat fully WT cells with IAA and test whether non-AID labelled H2 or RAD21 dip in intensity. If they do not, then perhaps there's a causal relationship between condensin II and cohesin levels?

According to the reviewer’s suggestion, we tested whether IAA treatment causes an unintentional decreases in the H2 or RAD21 signals in G2-arrested cells, and found that it is not the case (see the attached figure below).

Thus, these data indicate that there is a modest functional interdependence between condensin II and cohesin in G2-arrested cells. For instance, condensin II depletion may modestly destabilize chromatin-bound cohesin (and vice versa). However, we note that these effects are minor and do not affect the overall conclusions of the study. In the revised manuscript, we have described these potentially interesting observations briefly as a note in the corresponding figure legends (Fig. S4).

I recognise this is something considered in Brunner et al 2025 (JCB), but in their case they depleted SMC4 (so all condensins are lost or at least dismantled). Might bear further investigation.

Methods:

Data and methods are described in reasonable detail, and a decent number of replicates/statistical analyses have been. Documentation of the cell lines used could be improved. The actual cell line is not mentioned once in the manuscript. Although it is referenced, I'd recommend including the identity of the cell line (HCT116) in the main text when the cells are introduced and also in the relevant supplementary tables. Will make it easier for readers to contextualise the findings.

We apologize for the omission of important information regarding the parental cell line used in the current study. The information has been added to Materials and Methods as well as the resource table.

Minor comments:

Overall the manuscript is well-written and well presented. In the introduction it is suggested that no experiment has established a causal relationship between human condensin II and chromosome territories, but this is not correct, Hoencamp et al 2021 (cell) observed loss of CTs after condensin II depletion. Although that manuscript did not investigate it in as much detail as the present study, the fundamental relationship was previously established, so I would encourage the authors to revise this statement.

We are somewhat puzzled by this comment. In the original manuscript, we explicitly cited Hoencamp et al (2021) in support of the following sentences:

(Lines 78-83 in the original manuscript)

*Moreover, high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) analysis revealed that, under such conditions, chromosomes retain a parallel arrangement of their arms, reminiscent of the so-called Rabl configuration (Hoencamp et al., 2021). These findings indicate that the loss or impairment of condensin II during mitosis results in defects in post-mitotic chromosome organization. *

That said, to make the sentences even more precise, we have made the following revision in the manuscript.

(Lines 78- 82 in the revised manuscript)

*Moreover, high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) analysis revealed that, under such conditions, chromosomes retain a parallel arrangement of their arms, reminiscent of the so-called Rabl configuration (Hoencamp et al., 2021). These findings,together with cytological analyses of centromere distributions, indicate that the loss or impairment of condensin II during mitosis results in defects in post-mitotic chromosome organization. *

The following statement was intended to explain our current understanding of the maintenance of chromosome territories. Because Hoencamp et al (2021) did not address the maintenance of CTs, we have kept this sentence unchanged.

(Lines 100-102 in the original manuscript)

Despite these findings, there is currently no evidence that either condensin II, cohesin, or their combined action contributes to the maintenance of CT morphology in mammalian interphase cells (Cremer et al., 2020).

Reviewer #2 (Significance (Required)):

General assessment:

Strengths: the multiscale investigation of genome architecture at different stages of interphase allow the authors to present convincing and well-analysed data that provide meaningful insight into local and global chromosome organisation across different scales.

Limitations:

As suggested in major comments.

Advance:

Although the role of condensin II in generating chromosome territories, and the roles of cohesin in interphase genome architecture are established, the interplay of the complexes and the stage specific roles of condensin II have not been investigated in human cells to the level presented here. This study provides meaningful new insight in particular into the role of condensin II in global genome organisation during interphase, which is much less well understood compared to its participation in mitosis.

Audience:

Will contribute meaningfully and be of interest to the general community of researchers investigating genome organisation and function at all stages of the cell cycle. Primary audience will be cell biologists, geneticists and structural biochemists. Importance of genome organisation in cell/organismal biology is such that within this grouping it will probably be of general interest.

My expertise is in genome organization by SMCs and chromosome segregation.

We appreciate the reviewer’s supportive comments. As the reviewer fully acknowledges, this study is the first systematic survey of the collaborative role of condensin II and cohesin in establishing and maintaining interphase chromosome territories. In particular, multi-scale FISH analyses have enabled us to clarify how the two SMC protein complexes contribute to the maintenance of G2 chromosome territories through their actions at different genomic scales. As the reviewer notes, we believe that the current study will appeal to a broad readership in cell and chromosome biology. The limitations of the current study mentioned by the reviewer are addressed in our reply above.

Reviewer #3 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

Summary:

The manuscript “Condensin II collaborates with cohesin to establish and maintain interphase chromosome territories" investigates how condensin II and cohesin contribute to chromosome organization during the M-to-G1 transition and in G2 phase using published auxin-inducible degron (AID) cell lines which render the respective protein complexes nonfunctional after auxin addition. In this study, a novel degron cell line was established that enables the simultaneous depletion of both protein complexes, thereby facilitating the investigation of synergistic effects between the two SMC proteins. The chromosome architecture is studied using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and light microscopy. The authors reproduce a number of already published data and also show that double depletion causes during the M-to-G1 transition defects on chromosome territories, producing expanded, irregular shapes that obscure condensin II-specific phenotypes. Findings in G2 cells point to a new role of condensin II for chromosome conformation at a scale of ~20Mb. Although individual depletion has minimal effects on large-scale CT morphology in G2, combined loss of both complexes produces marked structural abnormalities, including irregular crescent-shaped CTs displaced toward the nucleolus and increased nucleolus-CT contact. The authors propose that condensin II and cohesin act sequentially and complementarily to ensure proper post-mitotic CT formation and maintain chromosome architecture across genomic scales.

We greatly appreciate the reviewer’s supportive comments. The reviewer has accurately recognized our new findings concerning the collaborative roles of condensin II and cohesin in the establishment and maintenance of interphase chromosome territories.

Concenrs about statistics:

- The authors provide the information on how many cells are analyzed but not the number of independent experiments. My concern is that there might variations in synchronization of the cell population and in the subsequent preparation (FISH) affecting the final result.

We appreciate the reviewer’s important comment regarding the biological reproducibility of our experiments. As the reviewer correctly points out, variations in cell-cycle synchronization and FISH sample preparation can occur across experiments. To address this concern, we repeated the key experiments supporting our main conclusions (Figs. 3 and 6) two additional times, resulting in three independent biological replicas in total. All replicate experiments reproduced the major observations from the original analyses. These results further substantiated our original conclusion, despite the inevitable variability arising from cell synchronization or sample preparation in this type of experiments. In the revised manuscript, we have now explicitly indicated the number of biological replicates in the corresponding figures.

The analyses of chromosome-arm conformation shown in Fig. 5 were already performed in three independent rounds of experiments, as noted in the original submission. In addition, similar results were already obtained in other analyses reported in the manuscript. For example, centromere dispersion was quantified using an alternative centromere detection method (related to Fig. 1), and distances between specific chromosomal sites were measured using different locus-specific probes (related to Figs. 2 and 4). In both cases, the results were consistent with those presented in the manuscript.

-

Statistically the authors analyze the effect of cells with induced degron vs. vehicle control (non-induced). However, the biologically relevant question is whether the data differ between cell lines when the degron system is induced. This is not tested here (cf. major concern 2 and 3).

See our reply to major concerns 2 and 3.

-

Some Journal ask for blinded analysis of the data which might make sense here as manual steps are involved in the data analysis (e.g. line 626 / 627the convex hull of the signals was manually delineated, line 635 / 636 Chromosome segmentation in FISH images was performed using individual thresholding). However personally I have no doubts on the correctness of the work.

We thank the reviewer for pointing out that some steps in our data analysis were performed manually, such as delineating the convex hull of signals and segmenting chromosomes in FISH and IF images using individual thresholds. These manual steps were necessary because signal intensities vary among cells and chromosomes, making fully automated segmentation unreliable. To ensure objectivity, we confirmed that the results were consistent across two independently established double-depletion cell lines, which produced essentially identical findings. In addition, we repeated the key experiments underpinning our main conclusions (Figs. 3 and 6) two additional times, and the results were fully consistent with the original analyses. Therefore, we are confident that our current data analysis approach does not compromise the validity of our conclusions. Finally, we appreciate the reviewer’s kind remark that there is no doubt regarding the correctness of our work.

Major concerns:

- Degron induction appears to delay in Rad21-AID#1 and Double-AID#1 cells the transition from M to G1, as shown in Fig. S1. After auxin treatment, more cells exhibit a G2 phenotype than in an untreated population. What are the implications of this for the interpretation of the experiments?

In our protocol shown in Fig. 1C, cells were released into mitosis after G2 arrest, and IAA was added 30 min after release. It is well established that cohesin depletion causes a prometaphase delay due to spindle checkpoint activation (e.g., Vass et al, 2003, Curr Biol; Toyoda and Yanagida, 2006, MBoC; Peters et al, 2008, Genes Dev), which explains why cells with 4C DNA content accumulated, as judged by FACS (Fig. S1). The same was true for doubly depleted cells. However, a fraction of cells that escaped this delay progressed through mitosis and enter the G1 phase of the next cell cycle. We selected these early G1 cells and used them for down-stream analyses. This experimental procedure was explicitly described in the legends of Fig. 1C and Fig. S1A as follows:

(Lines 934-937; Legend of Fig. 1C)

From the synchronized populations, early G1cells were selected based on their characteristic morphologies (i.e., pairs of small post-mitotic cells) and subjected to downstream analyses. Based on the measured nuclear sizes (Fig. S2 G), we confirmed that early G1 cells were appropriately selected.

(Lines 1114-1119; Legend of Fig. S1A)

In this protocol, ~60% of control and H2-depleted cells, and ~30% of Rad21-depleted and co-depleted cells, were successfully synchronized in G1 phase. The apparently lower synchronization efficiency in the latter two groups is attributable to the well documented mitotic delay caused by cohesin depletion (Hauf et al., 2005; Haarhuis et al., 2013; Perea-Resa et al., 2020). From these synchronized populations, early G1 cells were selected based on their characteristic morphologies (see the legend of Fig. 1 C).

Thus, using this protocol, we analyzed an early G1 cell population that had completed mitosis without chromosome segregation defects. We acknowledge that this represents a technically challenging aspect of synchronizing cell-cycle progression from M to G1 in HCT116 cells, whose synchronization efficiency is limited compared with that of HeLa cells. Nevertheless, this approach constitutes the most practical strategy currently available.

- Line 178 "In contrast, cohesin depletion had a smaller effect on the distance between the two site-specific probes compared to condensin II depletion (Fig. 2, C and E)." The data in Fig. 2 E show both a significant effect of H2 and a significant effect of RAD21 depletion. Whether the absolute difference in effect size between the two conditions is truly relevant is difficult to determine, as the distribution of the respective control groups also appears to be different.

This comment is well taken. Reviewer #1 has made a comment on the same issue. See our reply to Reviewer #1 (Other points, Figure 2E).

In brief, in the current study, we should focus on the differences between -IAA and +IAA within each cell line, rather than comparing the -IAA conditions across different cell lines. In this sense, a sentence in the original manuscript (lines 178-180) was misleading. In the revised manuscript, we have modified the corresponding and subsequent sentence as follows:

Although cohesin depletion had a marginal effect on the distance between the two site-specific probes (Fig.2, C and E), double depletion did not result in a significant change (Fig.2, D and E), consistent with the partial restoration of centromere dispersion (Fig. 1G).

- In Figures 3, S3 and related text in the manuscript I cannot follow the authors' argumentation, as H2 depletion alone leads to a significant increase in the CT area (Chr. 18, Chr. 19, Chr. 15). Similar to Fig. 2, the authors argue about the different magnitude of the effect (H2 depletion vs double depletion). Here, too, appropriate statistical tests or more suitable parameters describing the effect should be used. I also cannot fully follow the argumentation regarding chromosome elongation, as double depletion in Chr. 18 and Chr. 19 also leads to a significantly reduced circularity. Therefore, the schematic drawing Fig. 3 H (double depletion) seems very suggestive to me.

This comment is related to the comment above (Major comment #2). See our reply to Reviewer #1 (Other points, Figure 2E).

It should be noted that, in Figure 3 (unlike in Figure 2), we did not compare the different magnitudes of the effect observed between H2 depletion and double depletion. Thus, the reviewer’s comment that “Similar to Fig. 2, the authors argue about the different magnitude of the effect (H2 depletion vs double depletion) ” does not accurately reflected our description.

Moreover, while the distance between two specific loci (Fig. 2E) and CT circularity (Fig. 3G) are intuitively related, they represent distinct parameters. Thus, it is not unexpected that double depletion resulted in apparently different outcomes for the two measurements. Thus, the reviewer’s counter-argument is not strictly applicable here.

That said, we agree with the reviewer that our descriptions here need to be clarified.

The differences between H2 depletion and double depletion are two-fold: (1) centromere dispersion is suppressed upon H2 depletion, but not upon double depletion (Fig 1G); (2) the distance between Cen 12 and 12q15 increased upon H2 depletion, but not upon double depletion (Fig 2E).

We have decided to remove the “homologous pair overlap” panel (formerly Fig. 3E) from the revised manuscript. Accordingly, the corresponding sentence has been deleted from the main text. Instead, we have added a new panel of “aspect ratio”, defined as the ratio of the major to the minor axis (new Fig. 3F). While this intuitive parameter was altered upon condensin II depletion and double depletion, again, we acknowledge that it is not sufficient to convincingly distinguish between the elongated and cloud-like phenotypes proposed in the original manuscript. For these reasons, in the revised manuscript, we have toned down our statements regarding the differences in CT morphology between the two conditions. Nonetheless, together with the data from Figs. 1 and 2, it is clear that the Rabl configuration observed upon condensin II depletion is further exacerbated in the absence of cohesin. Accordingly, we have modified the main text and the cartoon (Fig 3H) to more accurately depict the observations summarized above.

- 5 and accompanying text. I agree with the authors that this is a significant and very interesting effect. However, I believe the sharp bends is in most cases an artifact caused by the maximum intensity projection. I tried to illustrate this effect in two photographs: Reviewer Fig. 1, side view, and Reviewer Fig. 2, same situation top view (https://cloud.bio.lmu.de/index.php/s/77npeEK84towzJZ). As I said, in my opinion, there is a significant and important effect; the authors should simply adjust the description.

This comment is well taken. We appreciate the reviewer’s effort to help clarify our original observations. We have therefore added a new section entitled “Limitations of the study” to explicitly describe the constrains of our current approach. That said, as the reviewer also acknowledges, our observations remain valid because all experiments were performed with appropriate controls.

Minor concerns:

-

I would like to suggest proactively discussing possible artifacts that may arise from the harsh conditions during FISH sample preparation.

We fully agree with the reviewer’s concerns. For FISH sample preparation, we used relatively harsh conditions, including (1) fixation under a hypotonic condition (0.3x PBS), (2) HCl treatment, and (3) a denaturation step. We recognize that these procedures inevitably affect the preservation of the original structure; however, they are unavoidable in the standard FISH protocol. We also acknowledge that our analyses were limited to 2D structures based on projected images, rather than full 3D reconstructions. These technical limitations are now explicitly described in a new section entitled “Limitations of the study”, and the technical details are provided in Materials and Methods.

-

It would be helpful if the authors could provide the original data (microscopic image stacks) for download.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion and understand that providing the original image stacks could be of interest to readers. We agree that if the nuclei were perfectly spherical, as is the case for example in lymphocytes, 3D image stacks would contain much more information than 2D projections. However, as is typical for adherent cultured cells, including the HCT116-derived cells used in this study, the nuclei are flattened due to cell adhesion to the culture dish, with a thickness of only about one-tenth of the nuclear diameter (10–20 μm). Considering also the inevitable loss of structural preservation during FISH sample preparation, we were concerned that presenting 3D images might confuse rather than clarify. We therefore believe that representing the data as 2D projections, while explicitly acknowledging the technical limitations, provides the clearest and most interpretable presentation of our results. These limitations are now described in a new section of the manuscript.

-

The authors use a blind deconvolution algorithm to improve image quality. It might be helpful to test other methods for this purpose (optional).

We thank the reviewer for this valuable suggestion and fully agree that it is a valid point. We recognize that alternative image enhancement methods can offer advantages, particularly for smaller structures or when multiple probes are analyzed simultaneously. In our study, however, the focus was on detecting whole chromosome territories (CTs) and specific chromosomal loci, which can be visualized clearly with our current FISH protocol combined with blind deconvolution. We therefore believe that the image quality we obtained is sufficient to support the conclusions of this manuscript.

Reviewer #3 (Significance (Required)):

Advance:

Ono et al. addresses the important question on how the complex pattern of chromatin is reestablished after mitosis and maintained during interphase. In addition to affinity interactions (1,2), it is known that cohesin plays an important role in the formation and maintenance of chromosome organization interphase (3). However, current knowledge does not explain all known phenomena. Even with complete loss of cohesin, TAD-like structures can be recognized at the single-cell level (4), and higher structures such as chromosome territories are also retained (5). The function of condensin II during mitosis is another important factor that affects chromosome architecture in the following G1 phase (6). Although condensin II is present in the cell nucleus throughout interphase, very little is known about the role of this protein in this phase of the cell cycle. This is where the present publication comes in, with a new double degron cell line in which essential subunits of cohesin AND condensin can be degraded in a targeted manner. I find the data from the experiments in the G2 phase most interesting, as they suggest a previously unknown involvement of condensin II in the maintenance of larger chromatin structures such as chromosome territories.

The experiments regarding the M-G1 transition are less interesting to me, as it is known that condensin II deficiency in mitosis leads to elongated chromosomes (Rabl configuration)(6), and therefore the double degradation of condensin II and cohesin describes the effects of cohesin on an artificially disturbed chromosome structure.

For further clarification, we provide below a table summarizing previous studies relevant to the present work. We wish to emphasize three novel aspects of the present study. First, newly established cell lines designed for double depletion enabled us to address questions that had remained inaccessible in earlier studies. Second, to our knowledge, no study has previously reported condensin II depletion, cohesin depletion and double depletion in G2-arrested cells. Third, the present study represents the first systematic comparison of two different stages of the cell cycle using multiscale FISH under distinct depletion conditions. Although the M-to-G1 part of the present study partially overlaps with previous work, it serves as an important prelude to the subsequent investigations. We are confident that the reviewer will also acknowledge this point.

cell cycle

cond II depletion

cohesin depletion

double depletion

M-to-G1

Hoencamp et al (2021); Abramo et al (2019); Brunner et al (2025);

this study

Schwarzer et al (2017);

Wutz et al (2017);

this study

this study

G2

this study

this study

this study

Hoencamp et al (2021): Hi-C and imaging (CENP-A distribution)

Abramo et al (2019): Hi-C and imaging

Brunner et al (2025): mostly imaging (chromatin tracing)

Schwarzer et al (2017); Wutz et al (2017): Hi-C

this study: imaging (multi-scale FISH)

General limitations:

(1) Single cell imaging of chromatin structure typically shows only minor effects which are often obscured by the high (biological) variability. This holds also true for the current manuscript (cf. major concern 2 and 3).

See our reply above.

(2) A common concern are artefacts introduced by the harsh conditions of conventional FISH protocols (7). The authors use a method in which the cells are completely dehydrated, which probably leads to shrinking artifacts. However, differences between samples stained using the same FISH protocol are most likely due to experimental variation and not an artefact (cf. minor concern 1).

See our reply above.

-

The anisotropic optical resolution (x-, y- vs. z-) of widefield microscopy (and most other light microscopic techniques) might lead to misinterpretation of the imaged 3D structures. This seems to be the cases in the current study (cf. major concern 4).

See our reply above.

-

In the present study, the cell cycle was synchronized. This requires the use of inhibitors such as the CDK1 inhibitor RO-3306. However, CDK1 has many very different functions (8), so unexpected effects on the experiments cannot be ruled out.

The current approaches involving FISH inevitably require cell cycle synchronization. We believe that the use of the CDK1 inhibitor RO-3306 to arrest the cell cycle at G2 is a reasonable choice, although we cannot rule out unexpected effects arising from the use of the drug. This issue has now been addressed in the new section entitled “Limitations of the study”.

Audience:

The spatial arrangement of genomic elements in the nucleus and their (temporal) dynamics are of high general relevance, as they are important for answering fundamental questions, for example, in epigenetics or tumor biology (9,10). The manuscript from Ono et al. addresses specific questions, so its intended readership is more likely to be specialists in the field.

We are confident that, given the increasing interest in the 3D genome and its role in regulating diverse biological functions, the current manuscript will attract the broad readership of leading journals in cell biology.

About the reviewer:

By training I'm a biologist with strong background in fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence in situ hybridization. In recent years, I have been involved in research on the 3D organization of the cell nucleus, chromatin organization, and promoter-enhancer interactions.

We greatly appreciate the reviewer’s constructive comments on both the technical strengths and limitations of our fluorescence imaging approaches, which have been very helpful in revising the manuscript. As mentioned above, we have decided to add a special paragraph entitled “Limitations of the study” at the end of the Discussion section to discuss these issues.

All questions regarding the statistics of angularly distributed data are beyond my expertise. The authors do not correct their statistical analyses for "multiple testing". Whether this is necessary, I cannot judge.

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. In our study, the primary comparisons were made between -IAA and +IAA conditions within the same cell line. Accordingly, the figures report P-values for these pairwise comparisons.

For the distance measurements, statistical evaluations were performed in PRISM using ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test), and the P-values shown in the figures are based on these analyses (Fig. 1, G and H; Fig. 2 E; Fig. 3 F and G; Fig. 4 F; Fig. 6 F [right]–H; Fig. S2 B and G; Fig. S3 D and H; Fig. S5 A [right] and B [right]; Fig. S8 B). While the manuscript focuses on pairwise comparisons between -IAA and +IAA conditions within the same cell line, we also considered potential differences across cell lines as part of the same ANOVA framework, thereby ensuring that multiple testing was properly addressed. Because cell line differences are not the focus of the present study, the corresponding results are not shown.

For the angular distribution analyses, we compared -IAA and +IAA conditions within the same cell line using the Mardia–Watson–Wheeler test; these analyses do not involve multiple testing (circular scatter plots; Fig. 5 C–E and Fig. S6 B, C, and E–H). In addition, to determine whether angular distributions exhibited directional bias under each condition, we applied the Rayleigh test to each dataset individually (Fig. 5 F and Fig. S6 I). As these tests were performed on a single condition, they are also not subject to the problem of multiple testing. Collectively, we consider that the statistical analyses presented in our manuscript appropriately account for potential multiple testing issues, and we remain confident in the robustness of the results.

Literature

Falk, M., Feodorova, Y., Naumova, N., Imakaev, M., Lajoie, B.R., Leonhardt, H., Joffe, B., Dekker, J., Fudenberg, G., Solovei, I. et al. (2019) Heterochromatin drives compartmentalization of inverted and conventional nuclei. Nature, 570, 395-399.

Mirny, L.A., Imakaev, M. and Abdennur, N. (2019) Two major mechanisms of chromosome organization. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 58, 142-152.

Rao, S.S.P., Huang, S.C., Glenn St Hilaire, B., Engreitz, J.M., Perez, E.M., Kieffer-Kwon, K.R., Sanborn, A.L., Johnstone, S.E., Bascom, G.D., Bochkov, I.D. et al. (2017) Cohesin Loss Eliminates All Loop Domains. Cell, 171, 305-320 e324.

Bintu, B., Mateo, L.J., Su, J.H., Sinnott-Armstrong, N.A., Parker, M., Kinrot, S., Yamaya, K., Boettiger, A.N. and Zhuang, X. (2018) Super-resolution chromatin tracing reveals domains and cooperative interactions in single cells. Science, 362.

Cremer, M., Brandstetter, K., Maiser, A., Rao, S.S.P., Schmid, V.J., Guirao-Ortiz, M., Mitra, N., Mamberti, S., Klein, K.N., Gilbert, D.M. et al. (2020) Cohesin depleted cells rebuild functional nuclear compartments after endomitosis. Nat Commun, 11, 6146.

Hoencamp, C., Dudchenko, O., Elbatsh, A.M.O., Brahmachari, S., Raaijmakers, J.A., van Schaik, T., Sedeno Cacciatore, A., Contessoto, V.G., van Heesbeen, R., van den Broek, B. et al. (2021) 3D genomics across the tree of life reveals condensin II as a determinant of architecture type. Science, 372, 984-989.

Beckwith, K.S., Ødegård-Fougner, Ø., Morero, N.R., Barton, C., Schueder, F., Tang, W., Alexander, S., Peters, J.-M., Jungmann, R., Birney, E. et al. (2023) Nanoscale 3D DNA tracing in single human cells visualizes loop extrusion directly in situ. BioRxiv 8 of 9https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.12.439407.

Massacci, G., Perfetto, L. and Sacco, F. (2023) The Cyclin-dependent kinase 1: more than a cell cycle regulator. Br J Cancer, 129, 1707-1716.

Bonev, B. and Cavalli, G. (2016) Organization and function of the 3D genome. Nat Rev Genet, 17, 661-678.

Dekker, J., Belmont, A.S., Guttman, M., Leshyk, V.O., Lis, J.T., Lomvardas, S., Mirny, L.A., O'Shea, C.C., Park, P.J., Ren, B. et al. (2017) The 4D nucleome project. Nature, 549, 219-226.

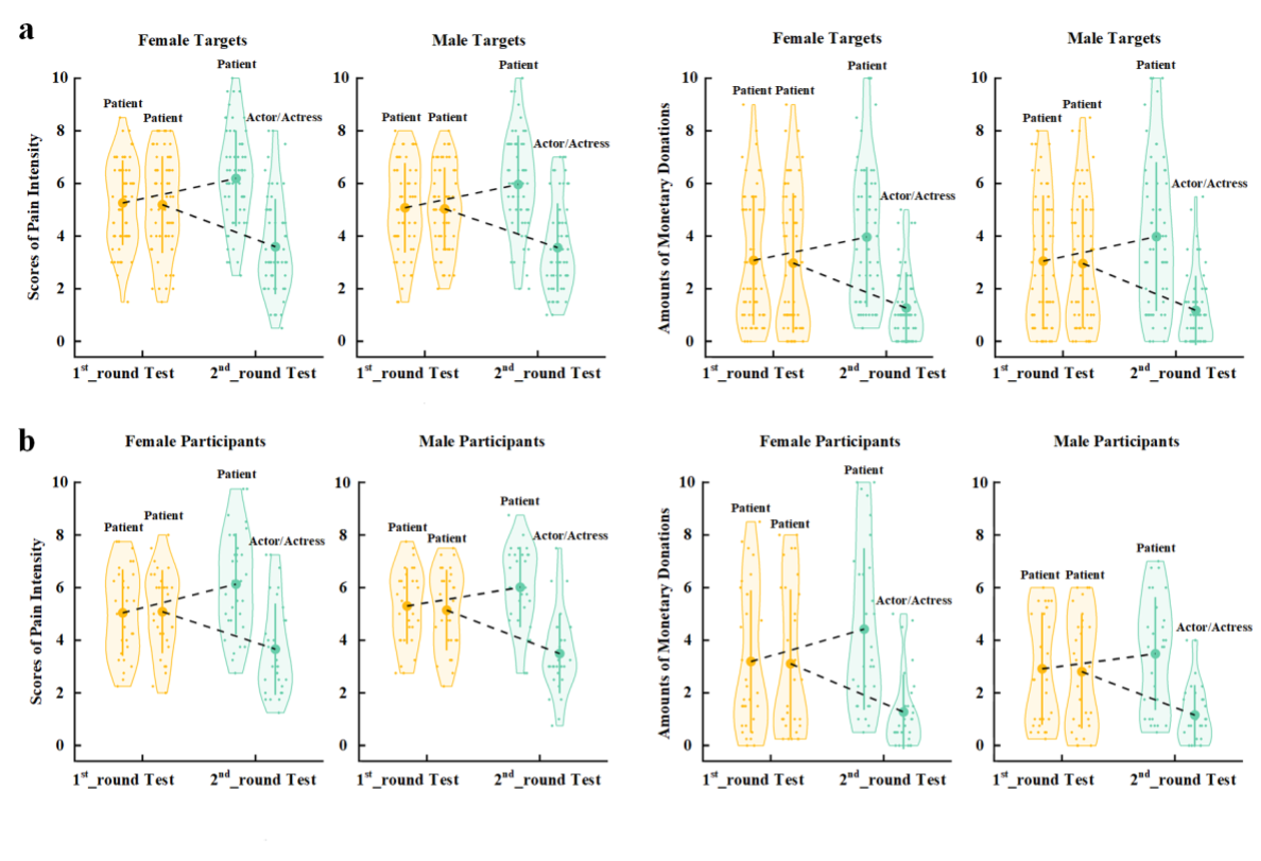

Supplementary Experiment Figure 1. EEG results of Supplementary Experiment 1. (a) Mean rating scores of happy intensity related to happy and neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. (b) ERPs to faces with awardee or actor/actress identities at the frontal electrodes. The voltage topography shows the scalp distribution of the P570 amplitude with the maximum over the central/parietal region. (c) Mean differential P570 amplitudes to happy versus neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. The voltage topographies illustrate the scalp distribution of the P570 difference waves to happy (vs. neutral) expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities, respectively. Shown are group means (large dots), standard deviation (bars), measures of each individual participant (small dots), and distribution (violin shape) in (a) and (c).

Supplementary Experiment Figure 1. EEG results of Supplementary Experiment 1. (a) Mean rating scores of happy intensity related to happy and neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. (b) ERPs to faces with awardee or actor/actress identities at the frontal electrodes. The voltage topography shows the scalp distribution of the P570 amplitude with the maximum over the central/parietal region. (c) Mean differential P570 amplitudes to happy versus neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. The voltage topographies illustrate the scalp distribution of the P570 difference waves to happy (vs. neutral) expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities, respectively. Shown are group means (large dots), standard deviation (bars), measures of each individual participant (small dots), and distribution (violin shape) in (a) and (c). Figure legend: (a) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female target faces. (b) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female participants.

Figure legend: (a) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female target faces. (b) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female participants.