Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This paper investigates the thermal and mechanical unfolding pathways of the doubly knotted protein TrmD-Tm1570 using molecular simulations, optical tweezers experiments, and other methods. In particular, the detailed analysis of the four major unfolding pathways using a well-established simulation method is an interesting and valuable result.

Strengths:

A key finding that lends credibility to the simulation results is that the molecular simulations at least qualitatively reproduce the characteristic force-extension distance profiles obtained from optical tweezers experiments during mechanical unfolding. Furthermore, a major strength is that the authors have consistently studied the folding and unfolding processes of knotted proteins, and this paper represents a careful advancement building upon that foundation.

We appreciate and we thank the reviewer for reading our manuscript.

Weaknesses:

While optical tweezers experiments offer valuable insights, the knowledge gained from them is limited, as the experiments are restricted to this single technique.

The paper mentions that the high aggregation propensity of the TrmD-Tm1570 protein appears to hinder other types of experiments. This is likely the reason why a key aspect, such as whether a ribosome or molecular chaperones are essential for the folding of TrmD-Tm1570, has not been experimentally clarified, even though it should be possible in principle.

We appreciate the suggestion that clarifying the requirement for molecular chaperones or the ribosome in TrmD-Tm1570 folding is crucial. We are pleased to report that the experiment investigating the role of molecular chaperones in the folding of TrmD-Tm1570 is currently under investigation in our laboratory. These results will provide the clarification on this aspect and will be incorporated into a future manuscript.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, the authors combined coarse-grained structure-based model simulation, optical tweezer experiments, and AI-based analysis to assess the knotting behavior of the TrmD-Tm1570 protein. Interestingly, they found that while the structure-based model can fold the single knot from TrmD and Tm1570, the double-knot protein TrmD-Tm1570 cannot form a knot itself, suggesting the need for chaperone proteins to facilitate this knotting process. This study has strong potential to understand the molecular mechanism of knotted proteins, supported by much experimental and simulation evidence. However, there are a few places that appear to lack sufficient details, and more clarification in the presentation is needed.

Strengths:

A combination of both experimental and computational studies.

We appreciate and we thank the reviewer for reading our manuscript.

Weaknesses:

There is a lack of detail to support some statements.

(1) The use of the AI-based method, SOM, can be emphasized further, especially in its analysis of the simulated unfolding trajectories and discovery of the four unfolding/folding pathways. This will strengthen the statistical robustness of the discovery.

We thank the reviewer for this observation. However, the AI-based method, SOM, was applied to obtain the main representative trajectories for the mechanical unfolding MD simulations. Specifically, for the TrmD, Tm1570, and fusion protein (TrmD-Tm1570) we extracted the representative conformational states by selecting the most highly populated SOM clusters shown in SI Figure 5 - figure supplement 3. Then, by identifying the cluster centroid, we selected the nearest point (simulations). These correspond to the clusters number 1 for Tm1570, number 11 for TrmD, and number 7 for TrmD-Tm1570. A sentence was added in the main manuscript to clarify how the main representative confirmation was obtained.

On the other hand, no AI‑based methods were applied to the thermal unfolding simulations. The four thermal unfolding trajectories shown in Figure 3 were obtained as follows: (i) trajectories where TrmD unfolds first and its knot unties before Tm1570 unfolds, corresponding to pathway 1 (Figure 3A and E); (ii) trajectories where Tm1570 unfolds and unties first, followed by TrmD, corresponding to pathway 3 (Figure 3C and G); and (iii) trajectories where TrmD unfolds first, then Tm1570, after which the TrmD knot unties and finally the Tm1570 knot unties—this corresponds to pathway 2. Pathway 4 follows the same sequence but in the reverse order.

(2) The manuscript would benefit from a clearer description of the correlation between the simulation and experimental results. The current correlation, presented in the paragraph starting from Line 250, focuses on measured distances. The authors could consider providing additional evidence on the order of events observed experimentally and computationally. More statistical analyses on the experimental curves presented in Figure 4 supplement would be helpful.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion. In response, we prepared additional statistical analyses in a table format reporting the average length‑change increments together with their standard deviations, and we clarified in the revised text that the ± values correspond to standard deviations. In addition, we quantified the percentage of TrmD, Tm1570, and TrmD-Tm1570 unfold completely, providing a clearer comparison of the order of events observed experimentally and computationally. These analyses have been incorporated into the revised manuscript, Tables 1 and 2.

(3) How did the authors calibrate the timescale between simulation and experiment? Specifically, what is the value \tau used in Line 270, and how was it calculated? Relevant information would strengthen the connection between simulation and experiment.

In our model time unit is defined by a relation  , where m is the reduced mass unit, is an average average mass of an amino acid, m = 110 Da = 1.66 x 10<sup>-27</sup> kg, 𝜀 is the reduced energy unit, an average interaction energy between amino acids. We may assume that ε is around 2-3 kcal/mol = 2-3 x 6.95 x 10<sup>-21</sup> J, is a distance unit and is equal to 1 nm.

, where m is the reduced mass unit, is an average average mass of an amino acid, m = 110 Da = 1.66 x 10<sup>-27</sup> kg, 𝜀 is the reduced energy unit, an average interaction energy between amino acids. We may assume that ε is around 2-3 kcal/mol = 2-3 x 6.95 x 10<sup>-21</sup> J, is a distance unit and is equal to 1 nm.

After plugging this values into the equation defining 𝜏 , we get: 𝜏 = 3.2 ps.

The definition of the time unit comes from the fact that this is how one can combine units of mass, distance and energy into an expression that has an unit of time.

The pulling speeds used in the simulations (0.05–0.15 Å/) correspond to approximately 1.6 -4.7 m/s in real units. These speeds are necessarily much higher than the experimental pulling The pulling speeds used in the simulations (0.05–0.15 Å/ ) correspond to approximately 1.6 - speed (20 nm/s), which is a well‑known limitation of steered molecular dynamics. However, our coarse‑grained model is run in an implicit solvent regime and does not explicitly include hydrodynamic friction. As a consequence, the simulated dynamics do not reproduce absolute real time kinetics. Instead, the comparison between simulation and experiment is made through relative unfolding pathways, force extension behavior, and contour length changes, which remain robust across the range of simulated pulling speeds.

Thus, 𝜏 = 3.2 ps is derived directly from the coarse‑grained model parameters rather than calibratedτ to experiment, and the connection between simulation and experiment is established through mechanistic agreement rather than matching absolute timescales.

We have now added a clarifying sentence to the manuscript (Methods and Materials - Mechanical unfolding simulations) explaining how the timescale was defined and how the value of was obtained.

Reference:

Szymczak, P., and Marek Cieplak. "Stretching of proteins in a uniform flow." The Journal of chemical physics 125.16 (2006).

(4) In Line 342, the authors comment that whether using native contacts or not, they cannot fold double-knotted TrmD-Tm1570. Could the authors provide more details on how non-native interactions were analyzed?

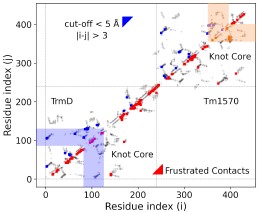

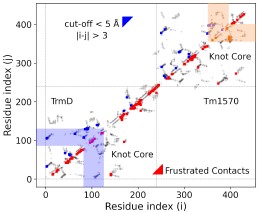

To analyze the role of non‑native interactions, we calculated two non‑native contact maps, first using a distance cutoff criterion and second by identifying the highly frustrated contacts based on the frustration index using Frustratometer (http://frustratometer.qb.fcen.uba.ar/) - figure below. From this procedure, the non‑native interactions were incorporated in the SBM C-alpha model to potentially assist refolding or knot formation. However, in neither case we observe successful refolding or the formation of the double‑knotted native topology. These results indicate that the addition of these non‑native contacts are insufficient to drive the refolding of the TrmD–Tm1570 protein. This result may suggest that the protein needs the support of chaperones or the active role of ribosomes to tie the two knots. We have now clarified this point more explicitly in the revised manuscript .

Author response image 1.

Native and non‑native contact maps for TrmD–Tm1570. The upper triangle (blue dots) corresponds to the cutoff‑based contact map and shows only unique contacts not present in the native contact map. The lower triangle (red dots) represents highly frustrated contacts, again showing only unique contacts absent from the native map. Black dots indicate the native contacts derived from the structure, and the contact map was generated using the Shadow Contact Map software. The blue and orange shadows correspond to the knot position for TrmD and Tm1570 proteins, respectively.

(5) It appears that the manuscript lacks simulation or experimental evidence to support the statement at Line 343: While each domain can self-tie into its native knot, this process inhibits the knotting of the other domain. Specifically, more clarification on this inhibition is needed.

Explaining this phenomenon remains challenging, and several contributing factors are likely.

(1) The folding success rates of the individual TrmD and Tm1570 domains are low (<3%); folding of the double-knotted protein is therefore expected to be even less efficient.

(2) While formation of a single knot is observed when the two domains are examined, the folded domain adopts a native-like but not fully native conformation, regardless of whether it is TrmD or Tm1570. (2A) Fluctuations of the unfolded second domain may impose a destabilizing load, promoting unfolding of the folded domain. (2B) Conversely, folding of one domain restricts the conformational space available to the other. Such restriction may have either stabilizing or destabilizing effects: although reduced conformational space (crowding) is generally thought to increase the probability of knot formation in polymers, in this system the constraint is localized rather than global.

(3) It is possible that extending the simulations to much longer timescales would allow formation of the second knot; however, within the timescales accessible here, unfolding of the first knot is observed instead.

(4) The TrmD–Tm1570 protein forms a dimer with a well-defined interface, whereas our simulations were performed on a monomeric unit. Consequently, both domains are solvent-exposed, forming an open two-domain system with tRNA-binding elements that are not stabilized by intermolecular interactions.

Taken together, these factors preclude a quantitative assessment of the dominant contribution. Our results suggest that efficient folding may require assistance from molecular chaperones or an active role of the ribosome in coordinating formation of the two knots.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) The paper notes at the beginning of its results section that simulations aiming to fully fold the TrmD-Tm1570 protein from a denatured state were unsuccessful. While the failure to achieve complete folding is itself an instructive and important result, there is room for improvement in how it's presented. The authors provide no specific details on what actually occurred during these simulations. It is plausible that some intermediate state was reached, and one can imagine that the knotting of the C-terminal part, Tm1570, was partially completed. A more detailed description of these outcomes would have been beneficial.

In the main manuscript (Figure 3), we reported the folding trajectories and the probability of native contact formation for the TrmD–Tm1570 protein, focusing on the four main observed unfolding pathways from our simulations. In addition to these common pathways, we also examined a small number of trajectories which one or both domains may refold. These are presented in Figure 3 - figure supplements 1 and 2, where we highlight a set of trajectories that we classify as rare events. In these rare trajectories, partial refolding and the formation of intermediate states can indeed be observed. However, as described in the main text, successful refolding of the fusion protein only occurs when the knot remains close to its native position and does not undergo large fluctuations along the chain. When the knot drifts significantly, refolding is not completed.

Figure 3 - figure supplement 1 shows six representative examples of intermediate states sampled during these simulations. As the reviewer suggested, some intermediate conformations were reached, including partial reformation of structural elements. However, only the trajectory which maintains the knot sufficiently close to its native location is able to do substantial refolding. We have now clarified this point more explicitly in the revised manuscript to better explain why full folding was not achieved and how the knot dynamics constrain the refolding process.

(2) Is it not possible to plot the degree of knot formation as a function of time or Q in Figure 3A-H? Doing so would make the verbally described results much clearer.

We thank the reviewer for the suggestion. Based on your observation, we have added a new figure in the SI manuscript (Figure 3 - figure supplement 3) showing the knot translocation as a function of the frames with their respective structure representations from the transitions, from folded to unfolded state and knot untied processes.

(3) Placement of a paragraph starting from line 250 looks odd to me. The paragraph describes simulation results of the mechanical unfolding, which is fully described in the following section. Specifically, the simulation result is discussed before describing its method/outline, which is to be avoided as far as possible.

According to the standard journal style, the Method section is described after the Discussion section. However, in the simulation's results, a sentence addressing the methods was included to guide the reader through the text.

(4) This is only an optional request. It is highly desired to examine the in vitro folding of TrmD-Tm1570 with and without molecular chaperones. At least, authors can envision/discuss this direction.

We agree that examining the in vitro folding of TrmD–Tm1570 with and without molecular chaperones would provide important mechanistic insights into the role of the fold of knotted proteins. We are planning to perform these experiments as part of our ongoing work, and in the revised manuscript we will add a discussion on this direction and its potential impact.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) Figure 6C was not referenced or discussed in the manuscript.

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. Figure 6C is indeed referenced and discussed in the manuscript.

(2) Several places refer to figures in the Supporting Information, and should be updated to refer to the supplement figures associated with the main figures.

In the revised version we ensure that all references are updated and clearly labeled.