- Oct 2022

-

minnstate.pressbooks.pub minnstate.pressbooks.pub

-

I might even say the best books are the best books because they stubbornly defy being reduced to a synopsis and some notes. Another way of saying that is, great books have so much in them that many different people with many different interests can all find something they’ll value in their pages.

This might be said of art, design, or any pursuit. Any design might comprise hundreds of design decisions. The more there are, the more depth to the design, the more facets of the problem space it has examined, the more knowledge it may contain, the more potential to learn.

-

-

-

Andere Sammlungen sind ihrem Verwendungszweck nie zugeführt worden. Der Germanist Friedrich Kittler etwa legte Karteikarten zu allen Farben an, die dem Mond in der Lyrik zugeschrieben worden sind. Das Buch dazu könnte jemand mit Hilfe dieser Zettel schreiben.

machine translation (Google):

Other collections have never been used for their intended purpose. The Germanist Friedrich Kittler, for example, created index cards for all the colors that were ascribed to the moon in poetry. Someone could write the book about it with the help of these slips of paper.

Germanist Friedrich Kittler collected index cards with all the colors that were ascribed to the moon in poetry. He never did anything with his collection, but it has been suggested that one could write a book with his research collection.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Blumenberg’s near-obsessive reliance on this writing machinery

Helbig indicates that Hans Blumenberg had a "near obsessive reliance on [his Zettelkasten as] writing machinery.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Film making is like note taking

Incidentally, one should note that the video is made up of snippets over time and then edited together at some later date. Specifically, these snippets are much like regularly taken notes which can then be later used (and even re-used--some could easily appear in other videos) to put together some larger project, namely this compilation video of his process. Pointing out this parallel between note taking and movie/videomaking, makes the note taking process much more easily seen, specifically for students. Note taking is usually a quite and solo endeavor done alone, which makes it much harder to show and demonstrate. And when it is demonstrated or modeled, it's usually dreadfully boring and uninteresting to watch compared to seeing it put together and edited as a finished piece. Edits in a film are visually obvious while the edits in written text, even when done poorly, are invisible.

-

Ryan Holiday does touch on all parts of his writing process, but the majority of the video is devoted to the sorts of easier bikeshedding ideas that people are too familiar with (editing, proofreading, title choice, book cover choice). Hidden here is the process of researching, writing, notes, and actual organizing process which are the much harder pieces for the majority of writers. Hiding it does a massive disservice to those watching it for the most essential advice they're looking for.

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>u/taurusnoises</span> in One of the ways I use my zettelkasten (though Obsidian) to write essays : Zettelkasten (<time class='dt-published'>08/10/2022 12:28:58</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

read.aupress.ca read.aupress.ca

-

The freedom to play with ideas, and to explore new ways of thinking, critiquing, deploying, and analyzing ed tech provided by metaphors, is much needed if we are to develop a better appreciation of its possibilities, implications, and limitations.

"Playful" activity as inherently "free" and actively necessary - compare to earlier sentence about whether that's "appropriate in the formal requirements" of a job.

-

-

johannadaniel.fr johannadaniel.fr

-

Fichiers et fiches de lecture autour des Souffrances du jeune Werther de Goethe

Files and reading sheets around the Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe

And you thought your slip boxes were DIY?!?

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Here again we seethe emphasis on writing as a movement that resists reification andall the intimidations of language. It is not surprising that Barthesshould have sought a form that would foster this infinite process. Theform lay, not in the fragment as such, but in the organization orarrangement that could be made from the fragments. He underlinedthis on an unpublished index card from 16 July 1979: ‘I can clearlysee this much (I think): my “notes” (Diary) as such, are not enough (Iincline towards them but in fact they’re a failure). What’s needed isanother turn of the screw, a “key”, which will turn these Notes-Diaryinto the mere notes of work that will be constructed and writtencontinuously: basically, to write notes, the index cards: to classifythem, turn them into bundles, and as I usually do, compose by takingone bundle after another.’11

-

-

Local file Local file

-

The most important thing about research is to know when to stop.How does one recognize the moment? When I was eighteen orthereabouts, my mother told me that when out with a young man Ishould always leave a half-hour before I wanted to. Although I wasnot sure how this might be accomplished, I recognized the advice assound, and exactly the same rule applies to research. One must stopbefore one has finished; otherwise, one will never stop and neverfinish.

Barbara Tuchman analogized stopping one's research to going out on a date: one should leave off a half-hour before you really want to.

Liink to: This sounds suspiciously like advice about when to start writing, but slightly in reverse: https://hypothes.is/a/WeoX9DUOEe2-HxsJf2P8vw

One might also liken these processes to the idea of divergence and convergence as described by Tiago Forte and others.

-

Sincecopying is a chore and a bore, use of the cards, the smaller thebetter, forces one to extract the strictly relevant, to distill from thevery beginning, to pass the material through the grinder of one’s ownmind, so to speak.

Barbara Tuchman recommended using the smallest sized index cards possible to force one only to "extract the strictly relevant" because copying by hand can be both "a chore and a bore".

In the same address in 1963, she encourages "distill[ing] from the very beginning, to pass the material through the grinder of one's own mind, so to speak." This practice is similar to modern day pedagogues who encourage this practice, but with the benefit of psychology research to back up the practice.

This advice is two-fold in terms of filtering out the useless material for an author, but the grinder metaphor indicates placing multiple types of material in to to a processor to see what new combinations of products come out the other end. This touches more subtly on the idea of combinatorial creativity encouraged by Raymond Llull, Matt Ridley, et al. or the serendipity described by Niklas Luhmann and others.

When did the writing for understanding idea begin within the tradition? Was it through experience in part and then underlined with psychology research? Visit Ahrens' references on this for particular papers to read.

Link to modality shift research.

Tags

- ars excerpendi

- analogies

- note taking advice

- when to stop x

- divergence/convergence

- note card sizes

- Barbara Tuchman

- when to start x

- modality shifts

- dating

- writing for understanding

- writing advice

- reading with a pen in hand

- educational psychology

- combinatorial creativity

- research advice

Annotators

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Deutsch himself pointed to criticswho called him a ‘chiffonier’ or historical rag-picker, though he defended his ‘incon-venient though undeniable facts’ (Deutsch, 1916). A number of contemporaries recog-nized the limits of his interest in individual facts. ‘I get the impression’, one figure put it,‘that the charm of the facts of history, was so great for Deutsch, he lost himself socompletely . . . in the study of them, that he was never altogether able to say he is throughwith studying them and that he is ready for writing’ (Schulman, 1922). One review ofDeutsch’s Scrolls (1917), which collected some of his scattered articles, reflected thatthe articles lacked organization. ‘In order to obtain value,’ the reviewer insisted, ‘factsmust be organized . . . Isolate a fact as one isolates a germ in the laboratory, such a factbecomes worthless for historical purposes’ (Leiber, 1917).

Just as people chided Niklas Luhmann for his obtuseness in writing based on his zettelkasten, Gotthard Deutsch's critics felt he didn't write enough using his.

-

-

journals.sagepub.com journals.sagepub.com

-

Does Deutsch’s index constitute a great unwritten work of history, as some have claimed, or are the cards ultimately useless ‘chips from his workshop’?

From his bibliography, it appears that Deutsch was a prolific writer and teacher, so how will Lustig (or others he mentions) make the case that his card index was useless "chips from his workshop"? Certainly he used them in writing his books, articles, and newspaper articles? He also was listed as a significant contributor to an encyclopedia as well.

It'd be interesting to look at the record to see if he taught with them the way Roland Barthes was known to have done.

-

-

forums.nanowrimo.org forums.nanowrimo.org

-

https://forums.nanowrimo.org/t/linking-up-zettelkasten-or-card-index-method-writers/433719

Looking for writers who are using an index card-based, Zettelkasten (German translation: slip box), or fichier boîte method for writing. Both traditional methods in the vein of Vladimir Nabokov, Michael Ende, Anne Lamott, Roland Barthes, Umberto Eco, or Robert Pirsig as well as Niklas Luhmann-esque methods (perhaps better for non-fiction) are fine.

Commonplace book practitioners are also welcome.

How many index cards will it take you to get to 50,000 words? (Reminder: It’s easier to write a few sentences or an index card at a time than focusing on thousands of words a day…)

-

-

forums.nanowrimo.org forums.nanowrimo.org

-

Writing4ever_3

Even if your raw typing is 60+ wpm, it doesn't help if you're actively composing at the same time. If the words and ideas come to you at that speed and you can get it out, great, but otherwise focus on what you can do in 15 minute increments to get the ideas onto the page. If typing is holding you back, write by hand or try a tape recorder or voice to text software.

-

-

archive.org archive.org

-

https://archive.org/details/refiningreadingw0000meij/page/256/mode/2up?q=index+card

Refining, reading, writing : includes 2009 mla update card by Mei, Jennifer (Nelson, 2007)

Contains a very generic reference to note taking on index cards for arranging material, but of such a low quality in comparison to more sophisticated treatments in the century prior. Apparently by this time the older traditions have disappeared and have been heavily watered down into just a few paragraphs.

-

-

archive.org archive.org

-

Goutor only mentions two potential organizational patterns for creating output with one's card index: either by chronological order or topical order. (p34) This might be typical for a historian who is likely to be more interested in chronologies and who would have likely noted down dates within their notes.

-

I love the phrasing of the title of his penultimate section "Making the card-file work", which makes it seem like the card file is ultimately doing the work of writing. Ultimately however, it's the work that was put into it that makes the card file useful, a sentiment that Jacques Goutor emphasizes when he says "How well this succeeds depends partly upon what was put into the file, and partly on how it was put in." (p34)

-

For physical note taking on index cards or visualizations provided by computer generated graphs, one can physically view a mass of notes and have a general feeling if there is a large enough corpus to begin writing an essay, chapter, or book or if one needs to do additional research on a topic, or perhaps pick a different topic on which to focus.

(parts suggested by p7, though broadly obvious)

-

-

Local file Local file

-

From these considerations, I hope the reader will un-derstand that in a way I never " s t a r t " writing on a project;I am writing continuously, either in a more personal vein,in the files, in taking notes after browsing, or in moreguided endeavors

Seems similar to the advice within Ahrens. Did he have a section on not needing to "start" writing or at least not starting with a blank page?

Compare and contrast these, if so.

Link to: https://hyp.is/DJd2hDUQEe2BMGv-WFSnVQ/www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1210153

-

At any rate, someof this writing leads me to feel uneasy about the assump-tion that all the skills required to put a book together areexplicit and teachable, as are the deadbeat methods ofmuch orthodox social science today.

"deadbeat methods"... wowza!

-

certainly surrounding oneself with acircle of people who will listen and t a l k - - a n d at times theyhave to be imaginary characters--is one of them

Intellectual work requires "surfaces" to work against, almost as an exact analogy to substrates in chemistry which help to catalyze reactions. The surfaces may include: - articles, books, or other writing against which one can think and write - colleagues, friends, family, other thinkers, or even imaginary characters (as suggested by C. Wright Mills) - one's past self as instantiated by their (imperfect) memory or by their notes about excerpted ideas or their own thoughts

Are there any other surfaces we're missing?

-

he taking o f anote is an additional mechanism for comprehension ofwhat one is reading.

-

In the file, onecan experiment as a writer and thus develop o n e ' s ownpowers of expression.

-

I had readBalzac off and on during the forties, and been much takenwith his self-appointed task of " c o v e r i n g " all the majorclasses and types in the society of the era he wished tomake his own.

We write to understand, to learn, to make knowledge our own.

Tags

- rhetoric

- internalizing knowledge

- learning

- academic writing

- inspiration

- conversations with the text

- writing

- intellectual surfaces

- card index as writing teacher

- a writer writes always

- writing skills

- writing for understanding

- Honoré de Balzac

- muses

- card index for writing

- conversations between texts

- writing advice

- Hemingway's White Bull

- blank page

- conversations

- continuous writing

- knowledge work

- examples

- zettelkasten

Annotators

-

- Sep 2022

-

media2-production.mightynetworks.com media2-production.mightynetworks.com

-

Writing%has%never%given%me%any%pleasure.%

Good lord. Then don't write.

-

Whenever%the%writer%writes,%it’s%always%three%o’clock%in%the%morning,%it’s%always%three%or%four%or%five%o’clock%in%the%morning%in%his%head.

Interesting, and for those of us awake then, writing poems and songs and stories in the dark (sometimes, alas, that has been me), the night seems endless.

-

The%writer%trusts%nothing%he%writes

Thus, the revisions

-

The%moment%a%writer%knows%how%to%achieve%a%certain%effect,%the%method%must%be%abandoned.

Interesting. I like that it suggests forever exploration.

-

A%writer%loves%the%dark,%loves%it,%but%is%always%fumbling%around%in%the%light.%

This feels about right, to me, most of the time. You?

-

-

tracydurnell.com tracydurnell.com

-

Prioritizing thinking or wordcraft is an intriguing way to divide writers.

It's indeed an interesting distinction. Does it represent a different approach in starting point, or is it a deeper difference in artisanship? And there's a bridge needed I suppose. Just thinking does not lead to writing, only wordsmithing not to thought through storyline. I can think of fun and great non-fiction books that read more thought out, and those where wording was leading it seems. But is that sense proof of the actual process? Read Venkatesh original text.

If this is a useful distinction and ignoring the fact I'm not an author, I fall on the thinking side mostly. Back at uni I wrote columns where the words were leading the way though. Where the verbal construct was the fun, not conveying a point or story.

-

-

marymount.instructure.com marymount.instructure.com

-

Do’s 1. Write twenty minutes a day over a period of four days. Do this periodically. This way you wont feel overwhelmed. 2. Write in a private, safe, comfortable environment. 3. Write about issues you're currently living with, something youre thinking or dreaming about constantly, a trauma you've never disclosed or discussed or resolved. 4. Write about joys and pleasures, too. 5. Write about what happened. Write, too, about feelings about what happened. What do you feel? Why do you feel this way? Link events with feelings. 6. ‘Try to write an extremely detailed, organized, coherent, vivid, emotionally compelling narrative. Don’t worry about correctness, about grammar or punctuation. 7. Beneficial effects will occur even if no one reads your writing. If you choose to keep your writing and not discard it, you must safeguard it. 8. Expect, initially, that in writing in this way you will have complex and appropriately difficult feelings. Make sure you get support if you need it.

On the other side of my notecard, I wrote a set of warnings I'd gleaned from Pennebaker: Don’ts 1. Don’t use writing as a substitute for taking action. 2. Don't become overly intellectual. 3. Don’t use writing as a way of complaining. Use it, instead, to discover how and why you feel as you do. Simply complaining or venting will probably make you feel worse. 4. Don’t use your writing to become overly self-absorbed. Over- analyzing everything is counterproductive. 5. Don't use writing as a substitute for therapy or medical care.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

I recommended Paul Silvia’s bookHow to write a lot, a succinct, witty guide to academic productivity in the Boicean mode.

What exactly are Robert Boice and Paul Silvia's methods? How do they differ from the conventional idea of "writing"?

-

• Daily writing prevents writer’s block.• Daily writing demystifies the writing process.• Daily writing keeps your research always at the top of your mind.• Daily writing generates new ideas.• Daily writing stimulates creativity• Daily writing adds up incrementally.• Daily writing helps you figure out what you want to say.

What specifically does she define "writing" to be? What exactly is she writing, and how much? What does her process look like?

One might also consider the idea of active reading and writing notes. I may not "write" daily in the way she means, but my note writing, is cumulative and beneficial in the ways she describes in her list. I might further posit that the amount of work/effort it takes me to do my writing is far more fruitful and productive than her writing.

When I say writing, I mean focused note taking (either excerpting, rephrasing, or original small ideas which can be stitched together later). I don't think this is her same definition.

I'm curious how her process of writing generates new ideas and creativity specifically?

One might analogize the idea of active reading with a pen in hand as a sort of Einsteinian space-time. Many view reading and writing as to separate and distinct practices. What if they're melded together the way Einstein reconceptualized the space time continuum? The writing advice provided by those who write about commonplace books, zettelkasten, and general note taking combines an active reading practice with a focused writing practice that moves one toward not only more output, but higher quality output without the deleterious effects seen in other methods.

-

. Remove Boice from the equation, and the existing literature on scholarly writing offerslittle or no conclusive evidence that academics who write every day are any more prolific,productive, or otherwise successful than those who do not.

There is little if any research that writing every day has any direct benefits.

-

Sword, Helen. “‘Write Every Day!’: A Mantra Dismantled.” International Journal for Academic Development 21, no. 4 (October 1, 2016): 312–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1210153

-

-

twitter.com twitter.comTwitter1

-

@BenjaminVanDyneReplying to @ChrisAldrichI wish I had a good answer! The book I use when I teach is Joseph Harris’s “rewriting” which is technically a writing book but teaches well as a book about how to read in a writerly way.

Thanks for this! I like the framing and general concept of the book.

It seems like its a good follow on to Dan Allosso's OER text How to Make Notes and Write https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/write/ or Sönke Ahrens' How to Take Smart Notes https://amzn.to/3DwJVMz which includes some useful psychology and mental health perspective.

Other similar examples are Umberto Eco's How to Write a Thesis (MIT, 2015) or Gerald Weinberg's The Fieldstone Method https://amzn.to/3DCf6GA These may be some of what we're all missing.

I'm reminded of Mark Robertson's (@calhistorian) discussion of modeling his note taking practice and output in his classroom using Roam Research. https://hyp.is/QuB5NDa0Ee28hUP7ExvFuw/thatsthenorm.com/mark-robertson-history-socratic-dialogue/ Perhaps we need more of this?

Early examples of this sort of note taking can also be seen in the religious studies space with Melanchthon's handbook on commonplaces or Jonathan Edwards' Miscellanies, though missing are the process from notes to writings. https://www.logos.com/grow/jonathan-edwards-organizational-genius/

Other examples of these practices in the wild include @andy_matuschak's https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DGcs4tyey18 and TheNonPoet's https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_sdp0jo2Fe4 Though it may be better for students to see this in areas in which they're interested.

Hypothes.is as a potential means of modeling and allowing students to directly "see" this sort of work as it progresses using public/semi-public annotations may be helpful. Then one can separately model re-arranging them and writing a paper. https://web.hypothes.is/

Reply to: https://twitter.com/BenjaminVanDyne/status/1571171086171095042

-

-

Local file Local file

-

As I write this book, for instance, I am sitting in a small room, beforea laptop computer, surrounded by books, papers, and magazines—all ofwhich I am, in some metaphorical sense, “in conversation with” (in muchthe same way I am also in conversation with you, my imagined reader).But what I am actually doing is working with a set of materials—lookingfor books on my shelves and flipping through them, folding pages over ormarking them with Post-its, retyping passages, filing and retrieving print-outs and photocopies, making notes in margins and on index cards, and,of course, composing, cutting, pasting, formatting, revising, and printingblocks of prose. I am, that is, for the most part, moving bits of text and paperaround.

Joseph Harris uses a mélange of materials to make his writing including books, papers, magazines, from which he is copying sections out, writing in margins, making notes on index cards and then moving those pieces of text and pieces of paper (the index cards, and possibly Post-it notes) around to create his output.

He doesn't delineate a specific process for his excerpting or note taking practice. How does he organize his notes? Is he just pulling them from piles around him? Is there a sense of organization at all?

-

Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How To Do Things With Texts. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2006. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/9248

-

-

-

Courtney, Jennifer Pooler. “A Review of Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts.” The Journal of Effective Teaching 7, no. 1 (2007): 74–77.

Review of: Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How To Do Things With Texts. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2006. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/9248.

-

Joseph Harris' text Rewriting: How to do things with texts (2006) sounds like a solid follow on text to the ideas found in Sönke Ahrens (2017) or Dan Allosso (2022).

-

Murray, D. M. (2000). The craft of revision (4th ed.). Boston: Harcourt College Publish-ers.

-

Elbow, P. (1999). Options for responding to student writing. In R. Straub (Ed.), Asourcebook for responding to student writing (pp. 197-202). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

-

many students andteachers confuse revising with editing.

-

Countering represents a writer attempting to “suggest a different way ofthinking” as opposed to attempting to “nullify” a writing (p. 57).

-

Harris further illustrates hisown idea of voices adding to an author’s text; each chapter contains multiple “intertexts,”which are small graphics with citation references to outside materials addressed nearby inthe text. These intertexts reinforce the practice of adding voices to the author’s docu-ment. These illustrations are effective; essentially, Harris is reflecting and modeling thepractice.

I quite like the idea of intertexts, which have the feeling of annotating one's own published work with the annotations of others. A sort of reverse annotation. Newspapers and magazines often feature pull quotes to draw in the reader, but why not have them as additional voices annotating one's stories or arguments.

This could certainly be done without repeating the quote twice within the piece.

-

too often students arelocked into a restricted win/lose view of academic writing.

-

This text fills a gap in the professional literature concerning revision because currently,according to Harris, there is little scholarship on “how to do it” (p. 7).

I'm curious if this will be an answer to the question I asked in Call for Model Examples of Zettelkasten Output Processes?

Tags

- Sönke Ahrens

- revision

- intertexts

- voices

- writing

- Joseph Harris

- Dan Allosso

- nullification

- reverse annotations

- marginalia

- composition

- want to read

- Donald Murray

- tools for thought

- game theory

- modelling behavior

- countering

- zettelkasten output

- note taking

- card index for writing

- revising

- open questions

- annotations

- reading practices

- writing advice

- references

- book reviews

- read

- Peter Elbow

- writing process

- editing

- argumentation

- active reading

Annotators

-

-

mleddy.blogspot.com mleddy.blogspot.com

-

https://mleddy.blogspot.com/2005/03/writing-and-index-cards.html

Looser tradition here for using index cards for writing. Comment have some interesting potential examples from circa 2005

-

-

mleddy.blogspot.com mleddy.blogspot.com

-

Isak Dinesen said that she wrote a little every day, without hope and without despair.

source? date? (obviously on/before 2005-09-22)

Any relation to Robert Boice's work on writing every day?

-

-

www.takenote.space www.takenote.space

-

I didn't see/couldn't find this image in the Life archive, but it was obviously contemporanous to the others

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

But having a conversation partner in your topic is actually ideal!

What's the solution: dig into your primary sources. Ask open-ended questions, and refine them as you go. Be open to new lines of inquiry. Stage your work in Conversation with so-and-so [ previously defined as the author of the text].

Stacy Fahrenthold recommends digging into primary sources and using them (and their author(s) as a "conversation partner". She doesn't mention using either one's memory or one's notes as a communication partner the way Luhmann does in "Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen" (1981), which can be an incredibly fruitful and creative method for original material.

-

-

www.tandfonline.com www.tandfonline.com

-

Sword, Helen. “‘Write Every Day!’: A Mantra Dismantled.” International Journal for Academic Development 21, no. 4 (October 1, 2016): 312–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1210153.

Preliminary thoughts prior to reading:<br /> What advice does Boice give? Is he following in the commonplace or zettelkasten traditions? Is the writing ever day he's talking about really progressive note taking? Is this being misunderstood?

Compare this to the incremental work suggested by Ahrens (2017).

Is there a particular delineation between writing for academic research and fiction writing which can be wholly different endeavors from a structural point of view? I see citations of many fiction names here.

Cross reference: Throw Mama from the Train quote

A writer writes, always.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

via

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>slide from tonight's class - when to write pic.twitter.com/6VjgdsUYNs

— Sister Sarah (@sarahdoingthing) June 20, 2017

-

-

images.google.com images.google.com

-

Author Vladimir Nabokov's researched materials on file cards for his book 'Lolita'.Location:Ithaca, NY, USDate taken:September 1958Photographer:Carl Mydans

-

-

images.google.com images.google.com

-

Uladimir Nabokov Ithaca, New YorkDate taken:1958Photographer:Carl Mydans

-

-

images.google.com images.google.com

-

Uladimir Nabokov Ithaca, New YorkDate taken:1958Photographer:Carl Mydans

-

-

images.google.com images.google.com

-

Author Vladimir Nabokov at work, writing on index cards in his car.Location:Ithaca, NY, USDate taken:September 1958Photographer:Carl MydansSize:1280 x 889 pixels (17.8 x 12.3 inches)

-

-

mleddy.blogspot.com mleddy.blogspot.com

-

After a leisurely lunch, prepared by the German cook who came with the house, I would spend another four-hour span in a lawn chair, among the roses and mockingbirds, using lined index cards and a Blackwing pencil, for copying and recopying, rubbing out and writing anew, the scenes I had imagined in the morning. Foreword to Lolita: A Screenplay (1973)

-

The manuscript, mostly a Fair Copy, from which the present text has been faithfully printed, consists of eighty medium-sized index cards, on each of which Shade reserved the pink upper line for headings (canto number, date) and used the fourteen light-blue lines for writing out with a fine nib in a minute, tidy, remarkably clear hand, the text of this poem, skipping a line to indicate double space, and always using a fresh card to begin a new canto. Pale Fire (1962) [From Charles Kinbote's foreword to his edition of John Shade's poem.]

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Posted byu/piloteris16 hours agoCreative output examples .t3_xdrb0k._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } I am curious about examples, if any, of how an anti net can be useful for creative or artistic output, as opposed to more strictly intellectual articles, writing, etc. Does anyone here use an antinet as input for the “creative well” ? I’d love examples of the types of cards, etc

They may not necessarily specifically include Luhmann-esque linking, numbering, and indexing, but some broad interesting examples within the tradition include: Comedians: (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettelkasten for references/articles) - Phyllis Diller - Joan Rivers - Bob Hope - George Carlin

Musicians: - Eminem https://boffosocko.com/2021/08/10/55794555/ - Taylor Swift: https://hypothes.is/a/SdYxONsREeyuDQOG4K8D_Q

Dance: - Twyla Tharpe https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B000SEOWBG/ (Chapter 6)

Art/Visual - Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas: https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/archive-collections/verkn%C3%BCpfungszwang-exhibition/mnemosyne-materials

Creative writing (as opposed to academic): - Vladimir Nabokov https://www.openculture.com/2014/02/the-notecards-on-which-vladimir-nabokov-wrote-lolita.html - Jean Paul - https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00168890.2018.1479240 - https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC34721 (German) - Michael Ende https://www.amazon.com/Michael-Endes-Zettelkasten-Skizzen-Notizen/dp/352271380X

-

-

-

Traditionally, doctoral students are expected to implicitly absorb thisargument structure through repeated reading or casual discussion.

The social annotation being discussed here is geared toward classroom work involving reading and absorbing basic literature in an area of the sort relating to lower level literature reviews done for a particular set of classes.

It is not geared toward the sort of more hard targeted curated reading one might do on their particular thesis topic, though this might work in concert with a faculty advisor on a 1-1 basis.

My initial thought on approaching the paper was for the latter and not the former.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Jeff Miller@jmeowmeowReading the lengthy, motivational introduction of Sönke Ahrens' How to Take Smart Notes (a zettelkasten method primer) reminds me directly of Gerald Weinberg's Fieldstone Method of writing.

reply to: https://twitter.com/jmeowmeow/status/1568736485171666946

I've only seen a few people notice the similarities between zettelkasten and fieldstones. Among them I don't think any have noted that Luhmann and Weinberg were both systems theorists.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Bibliographical Index Card File

Note that here in the index, Eco differentiates the index card file with the descriptor "bibliographical" as there is another card file that will play a part.

-

Eco, Umberto. How to Write a Thesis. Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2015. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/how-write-thesis

Tags

Annotators

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

Jeremy August 31 Flag I read the book based on your enthusiasm, Chris, and while I learned something from the chapters on making notes, I was very disappointed in the second half, on writing. He is so wrong on the passive I find it hard to believe he ever actually researched it. But no matter, he is in good company on that. I just hope not too many people think they will truly understand the passive after reading this book.

Repy to https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/comment/16382/#Comment_16382

@Jeremy I certainly take your point on that score. I had read through a previous edition of just the writing portion which was originally written by S.J. Allosso from a prior generation, so I didn't read through all of the second half of this edition of the book. I haven't compared them, so I'm not sure how much revision, if any, has happened in the writing advice part of the text. I was definitely more interested in his take on note making in the first half.

-

- Aug 2022

-

stackoverflow.com stackoverflow.com

-

I wrote my own OAuth 2 implementation in the end, it actually wasn't that hard once you understand the spec.

-

-

www.w3.org www.w3.org

-

A disadvantage seemed to me to be that it is not obvious which words take one to particularly important new material, but I imagine that one could indicate that in the text.

I don't understand this.

-

-

-

2012. Microsoft Writing Style Guide. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/style-guide/welcome/.

Other recommendable technical–writing style guides:

- Google developer documentation style guide

- Apple Style Guide

- Write the Docs, Accessibility guidelines

- Write the Docs, Reducing bias in your writing

- IBM developerWorks Editorial style guide

- Red Hat Technical Writing Style Guide

- Splunk Style Guide

- DigitalOcean Documentation Style Guide

- Salesforce Style Guide for Documentation and User Interface Text

- Rackspace Writing guidelines

- OpenStack Writing style

- MongoDB Documentation Style Guide

- Conscious Style Guide

- 18F Content Guide

- A11Y Style Guide

- Mailchimp Content Style Guide

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

Update now that I'm three years in to my PhD program and am about to start on my lit reviews and dissertation research... Holy Forking Shirtballs, am I glad I started my ZK back in 2020!!! * I cannot tell you how often I've used it to write my course papers. * I cannot tell you how often I've had it open during class discussions to back up my points. * I cannot tell you how lazy I've gotten with some of my entries (copying and pasting text instead of reworking it into my own words), and how much I wish I had taken the time to translate those entries for myself.

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

When Vladimir Nabokov died in 1977, he left instructions for his heirs to burn the 138 handwritten index cards that made up the rough draft of his final and unfinished novel, The Original of Laura. But Nabokov’s wife, Vera, could not bear to destroy her husband’s last work, and when she died, the fate of the manuscript fell to her son. Dmitri Nabokov, now seventy-five—the Russian novelist’s only surviving heir, and translator of many of his books—has wrestled for three decades with the decision of whether to honor his father’s wish or preserve for posterity the last piece of writing of one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century.

Nabokov's wishes were that his heirs burn the index cards on which he had handwritten the beginning of his unfinished novel The Original of Laura. His wife Vera, not able to destroy her husband's work, couldn't do it, so the decision fell to their son Dimitri. Having translated many of his father's works previously, Dimitri Nabokov ultimately allowed Penguin the right to publish the unfinished novel.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Allosso, Dan, and S. F. Allosso. How to Make Notes and Write. Minnesota State Pressbooks, 2022. https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/write/.

Annotatable .pdf copy for Hypothes.is: https://docdrop.org/pdf/How-to-Make-Notes-and-Write---Allosso-Dan-jzdq8.pdf/

Nota Bene:

These annotations are of a an early pre-release draft of the text. One ought to download the most recent revised/final/official draft at https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/write/.

-

-

threadreaderapp.com threadreaderapp.com

-

-

While Heyde outlines using keywords/subject headings and dates on the bottom of cards with multiple copies using carbon paper, we're left with the question of where Luhmann pulled his particular non-topical ordering as well as his numbering scheme.

While it's highly likely that Luhmann would have been familiar with the German practice of Aktenzeichen ("file numbers") and may have gotten some interesting ideas about organization from the closing sections of the "Die Kartei" section 1.2 of the book, which discusses library organization and the Dewey Decimal system, we're still left with the bigger question of organization.

It's obvious that Luhmann didn't follow the heavy use of subject headings nor the advice about multiple copies of cards in various portions of an alphabetical index.

While the Dewey Decimal System set up described is indicative of some of the numbering practices, it doesn't get us the entirety of his numbering system and practice.

One need only take a look at the Inhalt (table of contents) of Heyde's book! The outline portion of the contents displays a very traditional branching tree structure of ideas. Further, the outline is very specifically and similarly numbered to that of Luhmann's zettelkasten. This structure and numbering system is highly suggestive of branching ideas where each branch builds on the ideas immediately above it or on the ideas at the next section above that level.

Just as one can add an infinite number of books into the Dewey Decimal system in a way that similar ideas are relatively close together to provide serendipity for both search and idea development, one can continue adding ideas to this branching structure so they're near their colleagues.

Thus it's highly possible that the confluence of descriptions with the book and the outline of the table of contents itself suggested a better method of note keeping to Luhmann. Doing this solves the issue of needing to create multiple copies of note cards as well as trying to find cards in various places throughout the overall collection, not to mention slimming down the collection immensely. Searching for and finding a place to put new cards ensures not only that one places one's ideas into a growing logical structure, but it also ensures that one doesn't duplicate information that may already exist within one's over-arching outline. From an indexing perspective, it also solves the problem of cross referencing information along the axes of the source author, source title, and a large variety of potential subject headings.

And of course if we add even a soupcon of domain expertise in systems theory to the mix...

While thinking about Aktenzeichen, keep in mind that it was used in German public administration since at least 1934, only a few years following Heyde's first edition, but would have been more heavily used by the late 1940's when Luhmann would have begun his law studies.

https://hypothes.is/a/CqGhGvchEey6heekrEJ9WA

When thinking about taking notes for creating output, one can follow one thought with another logically both within one's card index not only to write an actual paper, but the collection and development happens the same way one is filling in an invisible outline which builds itself over time.

Linking different ideas to other ideas separate from one chain of thought also provides the ability to create multiple of these invisible, but organically growing outlines.

-

-

english.stackexchange.com english.stackexchange.com

-

Given that so much of the web environment isn't being written by writers who care, I'm increasingly seeing 'login' used as a verb.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Allosso, Dan, and S. F. Allosso. How to Make Notes and Write. Minnesota State Pressbooks, 2022. https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/write/.

-

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

This piece would benefit from better editing—e.g. its use of pronouns with an unnatural (or too-far-away) antecedent, dubious phrasing like "all the more", etc.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Selections from CarlyleEdited by H. W. BOYNTON. i2mo, cloth, 288 pages. Price, 75 cents.

And here I was not knowing who Carlyle was just a day or two ago and now I'm seeing advertisements for collections of his work! 😁

Apparently I've just been reading the wrong things and jumping back to the early 21st century is where it's all at.

-

-

-

Dutcher, George Matthew. “Directions and Suggestions for the Writing of Essays or Theses in History.” Historical Outlook 22, no. 7 (November 1, 1931): 329–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/21552983.1931.10114595

-

These Directions and suggestions were first cornpiled in1908, and the first edition was printed in 1911 for use in theauthor‘s own classes. The present edition is the result ofthorough revision and is planned for general use.

This will be much more interesting given that he'd first written about this topic in 1908 and has accumulated more experience since then.

Look for suggestions about the potential change in practice over the ensuing years.

Is the original version extant in his papers?

-

Mere paraphrasing the work of an-other is as offensive as direct copying. The discovery of ma-terials, the research, the oqanization of the material, theplan of treatment, and the literary composition should eachbe strictly the independent work of the student. H e shouldlearn not merely to collect facts on paper but also to as-similate them in his own mind 4then express them interms of his own thinking, while adhering to strict accuracyin the statement of facts.

-

Zn&tence on good style. Reasonable care in follow-ing these suggestions with regard to style is essential tothe production of an acceptable essay, and neglect of themwill affect unfavorably the grade to be assigned.

Sadly, he doesn't define "good style" here and only a paragraph after saying to avoid the style of Carlyle and Macaulay.

This paragraph is one of the several of the type that would more appropriately appear in a syllabus than in a published journal article on this particular topic. Thus the style is here is part journal article on writing, but also format which could be subsumed into syllabi by others.

-

One can't help but notice that Dutcher's essay, laid out like it is in a numbered fashion with one or two paragraphs each may stem from the fact of his using his own note taking method.

Each section seems to have it's own headword followed by pre-written notes in much the same way he indicates one should take notes in part 18.

It could be illustrative to count the number of paragraphs in each numbered section. Skimming, most are just a paragraph or two at most while a few do go as high as 5 or 6 though these are rarer. A preponderance of shorter one or two paragraphs that fill a single 3x5" card would tend to more directly support the claim. Though it is also the case that one could have multiple attached cards on a single idea. In Dutcher's case it's possible that these were paperclipped or stapled together (does he mention using one side of the slip only, which is somewhat common in this area of literature on note making?). It seems reasonably obvious that he's not doing more complex numbering or ordering the way Luhmann did, but he does seem to be actively using it to create and guide his output directly in a way (and even publishing it as such) that supports his method.

Is this then evidence for his own practice? He does actively mention in several places links to section numbers where he also cross references ideas in one card to ideas in another, thereby creating a network of related ideas even within the subject heading of his overall essay title.

Here it would be very valuable to see his note collection directly or be able to compare this 1927 version to an earlier 1908 version which he mentions.

-

The editors of the American historical re-vim suggest t o their reviewers that they should write “witlia scientific rather than a literary intention, and with definite-ness and precision in both praise and dispraise. I t is desiredthat the review of tlie book will be such as will convey t o thereader a clear and comprehensive notion of its nature, ofits contents, of its merits, of its place in the literature ofthe subject, and of the amount of its positive contributionto knowledge.

-

A tentative oiitline should be prepared as soonas ossible after beginning reading on the subject and modi-f i e f a s the progress of the work requires.

-

-

scottscheper.com scottscheper.com

-

https://scottscheper.com/letter/36/

Clemens Luhmann, Niklas' son, has a copy of a book written in German in 1932 and given to his father by Friedrich Rudolf Hohl which ostensibly is where Luhmann learned his zettelkasten technique. It contains a 34 page chapter titled Die Kartei (the Card Index) which has the details.

-

-

howaboutthis.substack.com howaboutthis.substack.com

-

Below is a two page spread summarizing a Fast Company.com article about the Pennebaker method, as covered in Timothy Wilson’s book Redirect:

Worth looking into this. The idea of the Pennebaker method goes back to a paper of his in 1986 that details the health benefits (including mental) of expressive writing. Sounds a lot like the underlying idea of morning pages, though that has the connotation of clearing one's head versus health related benefits.

Compare/contrast the two methods.

Is there research underpinning morning pages?

See also: Expressive Writing in Psychological Science https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1745691617707315<br /> appears to be a recap article of some history and meta studies since his original work.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Following. I haven’t found anything in years. I’m planning on building my own scraper for my bank this winter if I can’t find anything by then

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Glad you liked it. That's an example of the "let's let the zettelkasten direct my writing" approach. This is different than the "I have something I'm working on. Let's see if there's anything in the zettelkasten to support/refute it" approach, which I also do. So, I might call one "directive," and the other "supportive." (Although, I'm just making that up).

Different modes/approaches to writing when using a zettelkasten:<br /> - directive: let the zettelkasten direct the writing project - supportive: one has a particular writing project in mind and uses their zettelkasten collection to support their thinking and writing for that.

Are there other potential methods in addition to these two?

-

Hit me up. Happy to show my zettel-based writing, and how my notes translate into published content, both short- and long-form.

Thanks u/taurusnoises, your spectacular recent video "Using the Zettelkasten (and Obsidian) to Write an Essay https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9OUn2-h6oVc is about as close to the sort of public example of output creation I had been looking for!

I'm sure that there are other methods and workflows out there which vary by person, method, and modality (analog/digital) and it would be interesting to see what those practices look like as examples for others to use, follow, and potentially improve upon.

I particularly appreciate that your visual starting perspective of the graph view in Obsidian fairly closely mimics what an analog zettelkasten user might be doing and seeing within that modality.

I'm still collecting extant examples and doing some related research, but perhaps I'll have some time later in the year to do some interviews with particular people about how they're actively doing this as you suggested.

On a tangential note, I'm also piqued by some of the specific ideas you mention in your notes in the video as they relate to some work on orality and memory I've been exploring over the past several years. If you do finish that essay, I'd love to read the finished piece.

Thanks again for this video!

-

-

www.ijcai.org www.ijcai.org

-

Symbolic Synthesis of Fault-Tolerance Ratiosin Parameterised Multi-Agent Systems

-

-

minnstate.pressbooks.pub minnstate.pressbooks.pub

-

Writing about anything – a novel, a historical primary source, an exam question – is at least a three-way dialogue. In the case of this handbook the conversation is between me, the writer; you, the reader; and the material. Similarly, writing about something you have read or researched should serve at least three purposes: to explore the material; to describe your reactions to it; and to communicate with your reader.

Writing is a three-way dialog

First, it is a conversation between an author, a reader, and the material. It is also an exploration of your research, your reaction to the material, and what you—as the author—is trying to communicate to the reader. Keeping each component of these triplets in mind as the writing (and likely reviewing of the writing) happens makes for engaging reading.

-

-

escapingflatland.substack.com escapingflatland.substack.com

-

When I’m writing this, from March through August 2022

The author took time over a period of 5 months to put this essay together. That's impressive, in terms of effort put in and in terms of tenacity. How much of this time is to 'hold questions' as Johnnie Moore would say, to develop your thoughts iteratively. Could it have been done in index cards, under the radar, with the essay then a smaller effort, reduced to collating those index cards?

-

-

ljvmiranda921.github.io ljvmiranda921.github.io

-

I also mentioned Zettelkasten many times in this post, but I don’t do that anymore—I just did a 1-month dry run and it felt tiring. Pen and paper just gives me the bare essentials. I can get straight to work and not worry if something is a literature note or a permanent note.

What is it that was tiring about the practice? Did they do it properly, or was the focus placed on tremendous output driving the feeling of a need for commensurate tremendous input on a daily basis? Most lifetime productive users only made a few cards a day, but I get the feeling that many who start, think they should be creating 20 cards a day and that is definitely a road to burn out. This feeling is compounded by digital tools that make it easier to quickly capture ideas by quoting or cut and pasting, but which don't really facilitate the ownership of ideas (internalization) by the note taker. The work of writing helps to facilitate this. Apparently the framing of literature note vs. permanent note also was a hurdle in the collection of ideas moving toward the filtering down and refining of one's ideas. These naming ideas seem to be a general hurdle for many people, particularly if they're working without particular goals in mind.

Only practicing zettelkasten for a month is certainly no way to build real insight or to truly begin developing anything useful. Even at two cards a day and a minimum of 500-1000 total cards to see some serendipity and creativity emerge, one would need to be practicing for just over a year to begin seeing interesting results.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

For the sake of simplicity, go to Graph Analysis Settings and disable everything but Co-Citations, Jaccard, Adamic Adar, and Label Propogation. I won't spend my time explaining each because you can find those in the net, but these are essentially algorithms that find connections for you. Co-Citations, for example, uses second order links or links of links, which could generate ideas or help you create indexes. It essentially automates looking through the backlinks and local graphs as it generates possible relations for you.

comment on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9OUn2-h6oVc

-

-

slate.com slate.com

-

Its account of how Heft made his flag closely resembled the standard story, but instead of any assertion that it became the basis for the official design, it merely said that it was “considered Lancaster’s first.”

I'm having trouble parsing this.

-

-

thoughtcatalog.com thoughtcatalog.com

-

https://thoughtcatalog.com/ryan-holiday/2013/08/how-and-why-to-keep-a-commonplace-book/

An early essay from Ryan Holiday about commonplace books including how, why, and their general value.

Notice that the essay almost reads as if he's copying out cards from his own system. This is highlighted by the fact that he adds dashes in front 23 of his paragraphs/points.

-

As Raymond Chandler put it, “when you have to use your energy to put those words down, you are more apt to make them count.”

-

-

danallosso.substack.com danallosso.substack.com

-

https://danallosso.substack.com/p/announcing-how-to-make-notes-and

Congratulations @danallosso!

-

- Jul 2022

-

minnstate.pressbooks.pub minnstate.pressbooks.pub

-

For those curious about the idea of what students might do with the notes and annotations they're making in the margins of their texts using Hypothes.is, I would submit that Dan Allosso's OER handbook How to Make Notes and Write (Minnesota State Pressbooks, 2022) may be a very useful place to turn. https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/write/

It provides some concrete advice on the topic of once you've highlighted and annotated various texts for a course, how might you then turn your new understanding, ideas, and extant thinking work into a blogpost, essay, term paper or thesis.

For a similar, but alternative take, the book How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking by Sönke Ahrens (Create Space, 2017) may also be helpful as well. This text however requires purchase via Amazon and doesn't carry the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike (by-nc-sa 4.0) license that Dr. Allosso's does.

In addition to the online copy of the book, there's an annotatable .pdf copy available here: http://docdrop.org/pdf/How-to-Make-Notes-and-Write---Allosso-Dan-jzdq8.pdf/ though one can download .epub and .pdf copies directly from the Pressbooks site.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Finally, new notes should be connected with anexisting note when you add them to your system. I’lldescribe this in greater detail shortly; the point for now isthat linking a new thought to an existing train of thoughtseems to be a key to your note-making system workingfor you. Where does this new idea fit into your thoughtson an issue? Your questions about a topic? Your ideasabout a puzzle you’re working on understanding?Disciplining yourself to make this connection can be abit tough and time-consuming at first. It is worth theinvestment. Without understanding how these ideas thatinterest us fit together, all we have is a pile of unrelatedtrivia.

Writing and refining one's note about an idea can be key to helping one's basic understanding of that idea, but this understanding is dramatically increased by linking it into the rest of one's framework of understanding of that idea. A useful side benefit of creating this basic understanding and extending it is that one can also reuse one's (better understood) ideas to create new papers for expanding other's reading and subsequent understanding.

-

Also, trust me on this: the “Aha!” momentsbecome more frequent and rewarding, when you’rewriting thoughts down.

-

Writing is a craft for most of us, not an art.

Or framed differently:

The art in writing is knowing that it is really a craft.

-

-

writingcommons.org writingcommons.org

-

Synthesis notes are a strategy for taking and using reading notes that bring together—synthesize—what we read with our thoughts about our topic in a way that lets us integrate our notes seamlessly into the process of writing a first draft. Six steps will take us from reading sources to a first draft.

Similar to Beatrice Webb's definition of synthetic notes in My Apprentice (1926), thought this also includes movement into actually drafting writing.

What year was this written?

The idea here seems to be less discrete in the steps of the writing process and subsumes multiple things instead of breaking them into discrete conceptual parts. Has this been some of what has caused issues in the note taking to creation process in the last century?

-

-

www.hardscrabble.net www.hardscrabble.net

-

Here’s a quick blog post about a specific thing (making FactoryBot.lint more verbose) but actually, secretly, about a more general thing (taking advantage of Ruby’s flexibility to bend the universe to your will). Let’s start with the specific thing and then come back around to the general thing.

-

-

luhmann.surge.sh luhmann.surge.sh

-

Perhaps the best method would be to take notes—not excerpts, but condensed reformulations of what has been read.

One of the best methods for technical reading is to create progressive summarizations of what one has read.

-

-

medium.com medium.com

-

-

Robert uses a system based on flashcards

flashcards?!?!! A commonplace book done in index cards is NOT based on "flashcards". 🤮

Someone here is missing the point...

-

-

winnielim.org winnielim.org

-

I knew if I wanted this website – which is an extension of my consciousness – to truly thrive, I needed to work on it in a sustainable manner. Bit by bit I slowly transformed the way I thought about it. Previously I would only work on it if I had the energy to make wholesale, dramatic changes. These days I am glad if I made one small change.

Winnie later goes on to point out that this is much like gardening: it is a slow process, and the process has its seasons which wax and wane, expanding and contracting. You sow. You seed. You water. You fertilize. You wait. You pick weeds. You water. Pick some more weeds. You might prune. You flick off the japanese beetles. And because of the cyclical nature of the planet we inhabit, we also have periods where nothing grows, and the soil lies dormant. Waiting. Resting. This, too, can be embraced as we carve out our little corners of the web, and really all aspects of our lives. I know I'm nearly as tender to myself as I should be.

-

-

training.gov.au training.gov.au

-

store surplus and re-usable

Write labels / dates

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.solimanwrites.com www.solimanwrites.com

-

But I later realized writing is many things, one of which is the finished article you’re reading now. Mainly though, it’s a tool for thinking things through.

I've mentioned this elsewhere, but I'm skeptical of this popularly recurring take that says writing is thinking, or that thinking without writing really isn't thinking. If writing helps you think, it's better for you to know that than the alternative. But thinking is thinking, and writing is writing.

I worry with all the insistence around this view of writing as a precondition to real thinking that people who are thinking at or near capacity without writing will believe they're somehow missing something and waste a lot of cycles in frustration as they attempt to write and find that it doesn't do anything for them thoughtwise that they weren't already getting before.

-

Think about the sad essay we all used to write for your (insert language here) class: back then you didn’t have permission to generate original ideas.

I'm not sure that's the correct diagnosis.

Alternative take: you were not, at that point in your life, equipped to understand that you could be generating new ideas and that you should walk away from that writing course with an appreciation for writing as a vehicle for what you'd like to accomplish with a given subject/format. It's fine that you didn't—many people don't—and your instructors, institution, parents, community, etc. probably could have done a better job at communicating this to you, but it was there, and it was the point all along.

-

-

www.zylstra.org www.zylstra.org

-

At the same time, like Harold, I’ve realised that it is important to do things, to keep blogging and writing in this space. Not because of its sheer brilliance, but because most of it will be crap, and brilliance will only occur once in a while. You need to produce lots of stuff to increase the likelihood of hitting on something worthwile. Of course that very much feeds the imposter cycle, but it’s the only way. Getting back into a more intensive blogging habit 18 months ago, has helped me explore more and better. Because most of what I blog here isn’t very meaningful, but needs to be gotten out of the way, or helps build towards, scaffolding towards something with more meaning.

Many people treat their blogging practice as an experimental thought space. They try out new ideas, explore a small space, attempt to come to understanding, connect new ideas to their existing ideas.

Ton Zylstra coins/uses the phrase "metablogging" to think about his blogging practice as an evolving thought space.

How can we better distill down these sorts of longer ideas and use them to create more collisions between ideas to create new an innovative ideas? What forms might this take?

The personal zettelkasten is a more concentrated form of this and blogging is certainly within the space as are the somewhat more nascent digital gardens. What would some intermediary "idea crucible" between these forms look like in public that has a simple but compelling interface. How much storytelling and contextualization is needed or not needed to make such points?

Is there a better space for progressive summarization here so that an idea can be more fully laid out and explored? Then once the actual structure is built, the scaffolding can be pulled down and only the idea remains.

Reminiscences of scaffolding can be helpful for creating context.

Consider the pyramids of Giza and the need to reverse engineer how they were built. Once the scaffolding has been taken down and history forgets the methods, it's not always obvious what the original context for objects were, how they were made, what they were used for. Progressive summarization may potentially fall prey to these effects as well.

How might we create a "contextual medium" which is more permanently attached to ideas or objects to help prevent context collapse?

How would this be applied in reverse to better understand sites like Stonehenge or the hundreds of other stone circles, wood circles, and standing stones we see throughout history.

-

-

-

// NB: Since line terminators can be the multibyte CRLF sequence, care // must be taken to ensure we work for calls where `tokenPosition` is some // start minus 1, where that "start" is some line start itself.

I think this satisfies the threshold of "minimum viable publication". So write this up and reference it here.

Full impl.:

getLineStart(tokenPosition, anteTerminators = null) { if (tokenPosition > this._edge && tokenPosition != this.length) { throw new Error("random access too far out"); // XXX } // NB: Since line terminators can be the multibyte CRLF sequence, care // must be taken to ensure we work for calls where `tokenPosition` is some // start minus 1, where that "start" is some line start itself. for (let i = this._lineTerminators.length - 1; i >= 0; --i) { let current = this._lineTerminators[i]; if (tokenPosition >= current.position + current.content.length) { if (anteTerminators) { anteTerminators.push(...this._lineTerminators.slice(0, i)); } return current.position + current.content.length; } } return 0; }(Inlined for posterity, since this comes from an uncommitted working directory.)

-

-

www.remastery.net www.remastery.net

-

Beyond the cards mentioned above, you should also capture any hard-to-classify thoughts, questions, and areas for further inquiry on separate cards. Regularly go through these to make sure that you are covering everything and that you don’t forget something.I consider these insurance cards because they won’t get lost in some notebook or scrap of paper, or email to oneself.

Julius Reizen in reviewing over Umberto Eco's index card system in How to Write a Thesis, defines his own "insurance card" as one which contains "hard-to-classify thoughts, questions, and areas for further inquiry". These he would keep together so that they don't otherwise get lost in the variety of other locations one might keep them

These might be akin to Ahrens' "fleeting notes" but are ones which may not easily or even immediately be converted in to "permanent notes" for one's zettelkasten. However, given their mission critical importance, they may be some of the most important cards in one's repository.

link this to - idea of centralizing one's note taking practice to a single location

Is this idea in Eco's book and Reizen is the one that gives it a name since some of the other categories have names? (examples: bibliographic index cards, reading index cards (aka literature notes), cards for themes, author index cards, quote index cards, idea index cards, connection cards). Were these "officially" named and categorized by Eco?

May be worthwhile to create a grid of these naming systems and uses amongst some of the broader note taking methods. Where are they similar, where do they differ?

Multi-search tools that have full access to multiple trusted data stores (ostensibly personal ones across notebooks, hard drives, social media services, etc.) could potentially solve the problem of needing to remember where you noted something.

Currently, in the social media space especially, this is not a realized service.

-

- Jun 2022

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

I used to tell students (including PhD students) that 90% of what they will write will not be any good. But the only way they will get to the 10% that is good is by writing the 90% that isn't. So, they'd better start writing now! ;-)

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

All this hoopla seems out of character for the sedate man who likes to say of his work: ''Whatever I did, there was always someone around who was better qualified. They just didn't bother to do it.''

Very similar to Nike's tagline "Just Do It"

https://www.nytimes.com/1985/09/08/magazine/the-michener-phenomenon.html

-

-

warrenellis.ltd warrenellis.ltd

-

https://warrenellis.ltd/isles/wrangling-writing-on-wordpress/

-

-

Local file Local file

-

send off your draft or beta orproposal for feedback. Share this Intermediate Packet with a friend,family member, colleague, or collaborator; tell them that it’s still awork-in-process and ask them to send you their thoughts on it. Thenext time you sit down to work on it again, you’ll have their input andsuggestions to add to the mix of material you’re working with.

A major benefit of working in public is that it invites immediate feedback (hopefully positive, constructive criticism) from anyone who might be reading it including pre-built audiences, whether this is through social media or in a classroom setting utilizing discussion or social annotation methods.

This feedback along the way may help to further find flaws in arguments, additional examples of patterns, or links to ideas one may not have considered by themselves.

Sadly, depending on your reader's context and understanding of your work, there are the attendant dangers of context collapse which may provide or elicit the wrong sorts of feedback, not to mention general abuse.

-

Hemingway Bridge.” He wouldalways end a writing session only when he knew what came next inthe story. Instead of exhausting every last idea and bit of energy, hewould stop when the next plot point became clear. This meant thatthe next time he sat down to work on his story, he knew exactlywhere to start. He built himself a bridge to the next day, using today’senergy and momentum to fuel tomorrow’s writing.

It's easier to write when you know where you're going. As if to underline this Ernest Hemingway would end his writing sessions when he knew where he was going the following day so that it would be easier to pick up the thread of the story and continue on. (sourcing?)

(Why doesn't Forte have a source for this Hemingway anecdote? Where does it come from? He footnotes or annotates far more obscure pieces, why not this?!)

link to - Stephen Covey quote “begin with the end in mind” (did this prefigure the same common advice in narrative circles including Hollywood?)

-

An Archipelago of Ideas separates the two activities your brainhas the most difficulty performing at the same time: choosing ideas(known as selection) and arranging them into a logical flow (knownas sequencing).*

A missed opportunity to reference the arts of rhetoric here. This book is a clear indication that popular Western culture seems to have lost the knowledge of it.

As a reminder, in the review be sure to look at and critique the invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery of the piece as well as its ethos, pathos, and logos. :)

-

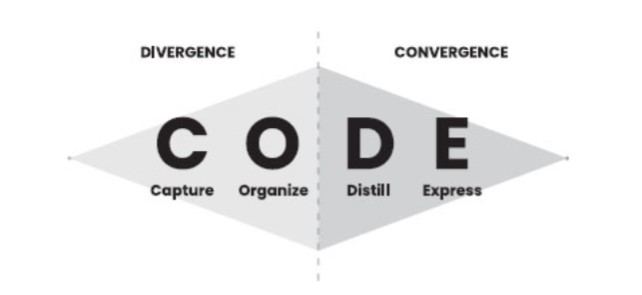

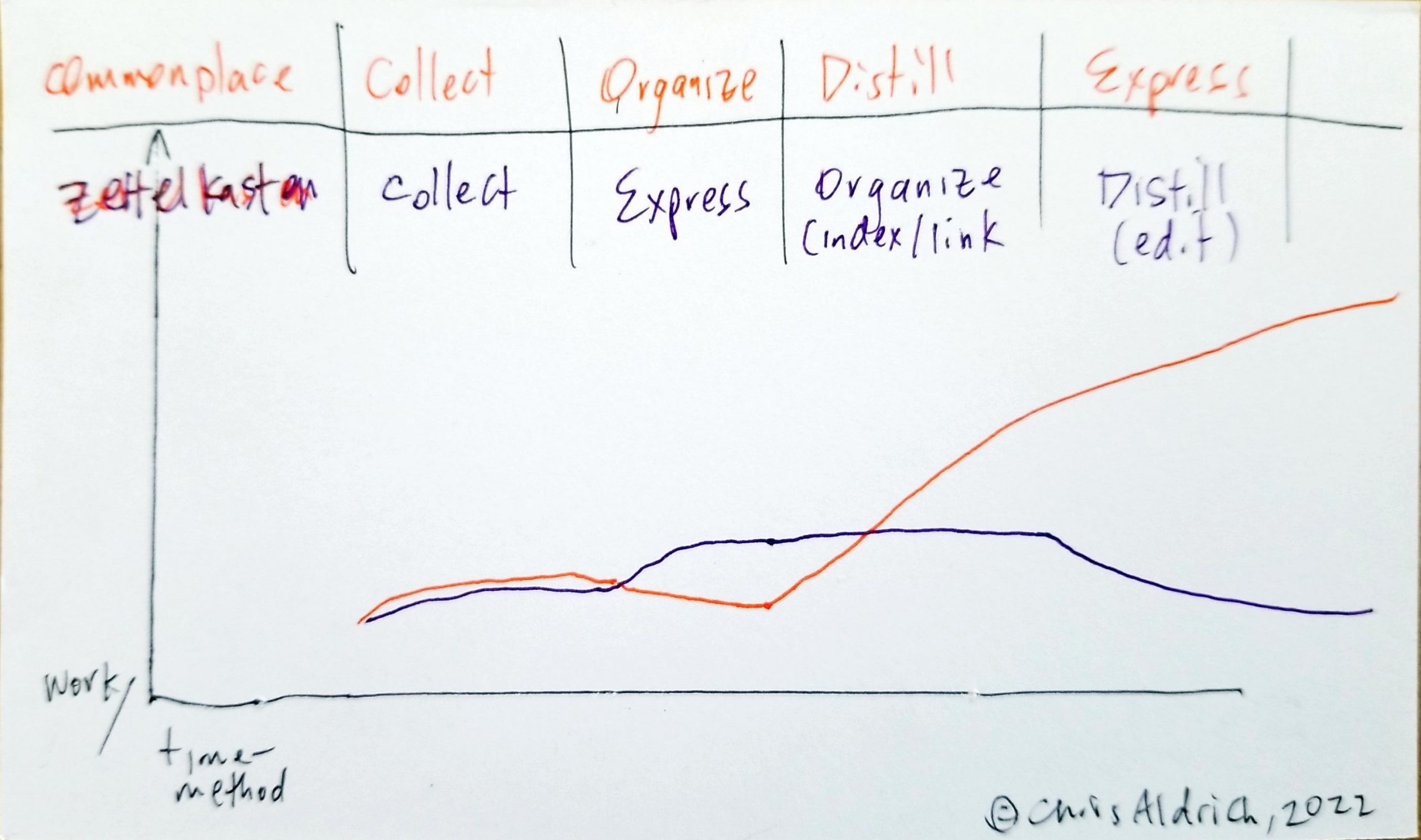

If we overlay the four steps of CODE onto the model ofdivergence and convergence, we arrive at a powerful template forthe creative process in our time.

The way that Tiago Forte overlaps the idea of C.O.D.E. (capture/collect, organize, distill, express) with the divergence/convergence model points out some primary differences of his system and that of some of the more refined methods of maintaining a zettelkasten.

<small>Overlapping ideas of C.O.D.E. and divergence/convergence from Tiago Forte's book Building a Second Brain (Atria Books, 2022) </small>

<small>Overlapping ideas of C.O.D.E. and divergence/convergence from Tiago Forte's book Building a Second Brain (Atria Books, 2022) </small>Forte's focus on organizing is dedicated solely on to putting things into folders, which is a light touch way of indexing them. However it only indexes them on one axis—that of the folder into which they're being placed. This precludes them from being indexed on a variety of other axes from the start to other places where they might also be used in the future. His method requires more additional work and effort to revisit and re-arrange (move them into other folders) or index them later.

Most historical commonplacing and zettelkasten techniques place a heavier emphasis on indexing pieces as they're collected.

Commonplacing creates more work on the user between organizing and distilling because they're more dependent on their memory of the user or depending on the regular re-reading and revisiting of pieces one may have a memory of existence. Most commonplacing methods (particularly the older historic forms of collecting and excerpting sententiae) also doesn't focus or rely on one writing out their own ideas in larger form as one goes along, so generally here there is a larger amount of work at the expression stage.

Zettelkasten techniques as imagined by Luhmann and Ahrens smooth the process between organization and distillation by creating tacit links between ideas. This additional piece of the process makes distillation far easier because the linking work has been done along the way, so one only need edit out ideas that don't add to the overall argument or piece. All that remains is light editing.

Ahrens' instantiation of the method also focuses on writing out and summarizing other's ideas in one's own words for later convenient reuse. This idea is also seen in Bruce Ballenger's The Curious Researcher as a means of both sensemaking and reuse, though none of the organizational indexing or idea linking seem to be found there.

This also fits into the diamond shape that Forte provides as the height along the vertical can stand in as a proxy for the equivalent amount of work that is required during the overall process.

This shape could be reframed for a refined zettelkasten method as an indication of work

Forte's diamond shape provided gives a visual representation of the overall process of the divergence and convergence.

But what if we change that shape to indicate the amount of work that is required along the steps of the process?!

Here, we might expect the diamond to relatively accurately reflect the amounts of work along the path.

If this is the case, then what might the relative workload look like for a refined zettelkasten? First we'll need to move the express portion between capture and organize where it more naturally sits, at least in Ahren's instantiation of the method. While this does take a discrete small amount of work and time for the note taker, it pays off in the long run as one intends from the start to reuse this work. It also pays further dividends as it dramatically increases one's understanding of the material that is being collected, particularly when conjoined to the organization portion which actively links this knowledge into one's broader world view based on their notes. For the moment, we'll neglect the benefits of comparison of conjoined ideas which may reveal flaws in our thinking and reasoning or the benefits of new questions and ideas which may arise from this juxtaposition.

This sketch could be refined a bit, but overall it shows that frontloading the work has the effect of dramatically increasing the efficiency and productivity for a particular piece of work.

Note that when compounded over a lifetime's work, this diagram also neglects the productivity increase over being able to revisit old work and re-using it for multiple different types of work or projects where there is potential overlap, not to mention the combinatorial possibilities.

--

It could be useful to better and more carefully plot out the amounts of time, work/effort for these methods (based on practical experience) and then regraph the resulting power inputs against each other to come up with a better picture of the efficiency gains.

Is some of the reason that people are against zettelkasten methods that they don't see the immediate gains in return for the upfront work, and thus abandon the process? Is this a form of misinterpreted-effort hypothesis at work? It can also be compounded at not being able to see the compounding effects of the upfront work.