"This implies that a sequence of uracils codes for phenylalanine, and our work suggests that it is probably a triplet of uracils." This was only a hypothesis when this paper was written and published, and now it is recognized as a biological fact. It's really crazy to see how quickly science can develop within just a few decades.

- Jan 2026

-

mssu.blackboard.com mssu.blackboard.comFile1

-

-

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the latest reviews:

"One remaining question is the interpretation of matching variants with very low stable posterior probabilities (~0), which the authors have analyzed in detail but without fully conclusive findings. I agree with the authors that this event is relatively rare and the current sample size is limited but this might be something to keep in mind for future studies."

Fine-mapping stability – on matching variants with very low stable posterior probability

We thank Reviewer 2 for encouraging us to think more about how low stable posterior probability matching variants can be interpreted. We describe a few plausible interpretations, even though – as Reviewer 2 and we have both acknowledged – our present experiments do not point to a clear and conclusive account.

One explanation is that the locus captured by the variant might not be well-resolved, in the sense that many correlated variants exist around the locus. Thus, the variant itself is unlikely causal, but the set of variants in high LD with it may contain the true causal variant, or it's possible that the causal variant itself was not sequenced but lies in that locus. A comparison of LD patterns across ancestries at the locus would be helpful here.

Another explanation rests on the following observation. For a variant to be matching between top and stable PICS and to also have very small stable PP, it has to have the largest PP after residualization on the ALL slice but also have positive PP with gene expression on many other slices. In other words, failing to control for potential confounders shrinks the PP. If one assumes that the matching variant is truly causal, then our observation points to an example of negative confounding (aka suppressor effect). This can occur when the confounders (PCs) are correlated with allele dosage at the causal variant in a different direction than their correlation with gene expression, so that the crude association between unresidualized gene expression and causal variant allele dosage is biased toward 0.

Although our present study does not allow us to systematically confirm either interpretation – since we found that matching variants were depleted in causal variants in our simulations, violating the second argument, but we also found functional enrichment in analyses of GEUVADIS data though only 17 matching variants with low stable PP were reported – we believe a larger-scale study using larger cohort sizes (at least 1000 individuals per ancestry) and many more simulations (to increase yield of such cases) would be insightful.

———

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews:

Reviewer #1:

Major comments:

(1) It would be interesting to see how much fine-mapping stability can improve the fine-mapping results in cross-population. One can simulate data using true genotype data and quantify the amount the fine-mapping methods improve utilizing the stability idea.

We agree, and have performed simulation studies where we assume that causal variants are shared across populations. Specifically, by mirroring the simulation approach described in Wang et al. (2020), we generated 2,400 synthetic gene expression phenotypes across 22 autosomes, using GEUVADIS gene expression metadata (i.e., gene transcription start site) to ensure largely cis expression phenotypes were simulated. We additionally generated 1,440 synthetic gene expression phenotypes that incorporate environmental heterogeneity, to motivate our pursuit of fine-mapping stability in the first place (see Response to Reviewer 2, Comment 6). These are described in Results section “Simulation study”:

We evaluated the performance of the PICS algorithm, specifically comparing the approach incorporating stability guidance against the residualization approach that is more commonly used — similar to our application to the real GEUVADIS data. We additionally investigated two ways of “combining” the residualization and stability guidance approaches: (1) running stability-guided PICS on residualized phenotypes; (2) prioritizing matching variants returned by both approaches. See Response to Reviewer 2, Comment 5.

(2) I would be very interested to see how other fine-mapping methods (FINEMAP, SuSiE, and CAVIAR) perform via the stability idea.

Thank you for this valuable comment. We ran SuSiE on the same set of simulated datasets. Specifically, we ran a version that uses residualized phenotypes (supposedly removing the effects of population structure), and also a version that incorporates stability. The second version is similar to how we incorporate stability in PICS. We investigated the performance of Stable SuSiE in a similar manner to our investigation of PICS. First we compared the performance relative to SuSiE that was run on residualized phenotypes. Motivated by our finding in PICS that prioritizing matching variants improves causal variant recovery, we did the same analysis for SuSiE. This analysis is described in Results section “Stability guidance improves causal variant recovery in SuSiE.”

We reported overall matching frequencies and causal variant recovery rates of top and stable variants for SuSiE in Figures 2C&D.

Frequencies with which Stable and Top SuSiE variants match, stratified by the simulation parameters, are summarized in Supplementary File 2C (reproduced for convenience in Response to Reviewer 2, Comment 3). Causal variant recovery rates split by the number of causal variants simulated, and stratified by both signal-to-noise ratio and the number of credible sets included, are reported in Figure 2—figure supplements 16-18. We reproduce Figure 2—figure supplement 18 (three causal variants scenario) below for convenience. Analogous recovery rates for matching versus non-matching top or stable variants are reported in Figure 2—figure supplements 19, 21 and 23.

(3) I am a little bit concerned about the PICS's assumption about one causal variant. The authors mentioned this assumption as one of their method limitations. However, given the utility of existing fine-mapping methods (FINEMAP and SuSiE), it is worth exploring this domain.

Thank you for raising this fair concern. We explored this domain, by considering simulations that include two and three causal variants (see Response to Reviewer 2, Comment 3). We looked at how well PICS recovers causal variants, and found that each potential set largely does not contain more than one causal variant (Figure 2—figure supplements 20 and 22). This can be explained by the fact that PICS potential sets are constructed from variants with a minimum linkage disequilibrium to a focal variant. On the other hand, in SuSiE, we observed multiple causal variants appearing in lower credible sets when applying stability guidance (Figure 2—figure supplements 21 and 23). A more extensive study involving more fine-mapping methods and metrics specific to violation of the one causal variant assumption could be pursued in future work.

Reviewer #2:

Aw et al. presents a new stability-guided fine-mapping method by extending the previously proposed PICS method. They applied their stability-based method to fine-map cis-eQTLs in the GEUVADIS dataset and compared it against what they call residualization-based method. They evaluated the performance of the proposed method using publicly available functional annotations and claimed the variants identified by their proposed stability-based method are more enriched for these functional annotations.

While the reviewer acknowledges the contribution of the present work, there are a couple of major concerns as described below.

Major:

(1) It is critical to evaluate the proposed method in simulation settings, where we know which variants are truly causal. While I acknowledge their empirical approach using the functional annotations, a more unbiased, comprehensive evaluation in simulations would be necessary to assess its performance against the existing methods.

Thank you for this point. We agree. We have performed a simulation study where we assume that causal variants are shared across populations (see response to Reviewer 1, Comment 1). Specifically, by mirroring the simulation approach described in Wang et al. (2020), we generated 2,400 synthetic gene expression phenotypes across 22 autosomes, using GEUVADIS gene expression metadata (i.e., gene transcription start site) to ensure cis expression phenotypes were simulated.

(2) Also, simulations would be required to assess how the method is sensitive to different parameters, e.g., LD threshold, resampling number, or number of potential sets.

Thank you for raising this point. The underlying PICS algorithm was not proposed by us, so we followed the default parameters set (LD threshold, r<sup>2</sup> \= 0.5; see Taylor et al., 2021 Bioinformatics) to focus on how stability considerations will impact the existing fine-mapping algorithm. We attempted to derive the asymptotic joint distribution of the p-values, but it was too difficult. Hence, we used 500 permutations because such a large number would allow large-sample asymptotics to kick in. However, following your critical suggestion we varied the number of potential sets in our analyses of simulated data. We briefly mention this in the Results.

“In the Supplement, we also describe findings from investigations into the impact of including more potential sets on matching frequency and causal variant recovery…”

A detailed write-up is provided in Supplementary File 1 Section S2 (p.2):

“The number of credible or potential sets is a parameter in many fine-mapping algorithms. Focusing on stability-guided approaches, we consider how including more potential sets for stable fine-mapping algorithms affects both causal variant recovery and matching frequency in simulations…

Causal variant recovery. We investigate both Stable PICS and Stable SuSiE. Focusing first on simulations with one causal variant, we observe a modest gain in causal variant recovery for both Stable PICS and Stable SuSiE, most noticeably when the number of sets was increased from 1 to 2 under the lowest signal-to-noise ratio setting…”

We observed that increasing the number of potential sets helps with recovering causal variants for Stable PICS (Figure 2—figure supplements 13-15). This observation also accounts for the comparable power that Stable PICS has with SuSiE in simulations with low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), when we increase the number of credible sets or potential sets (Figure 2—figure supplements 10-12).

(3) Given the previous studies have identified multiple putative causal variants in both GWAS and eQTL, I think it's better to model multiple causal variants in any modern fine-mapping methods. At least, a simulation to assess its impact would be appreciated.

We agree. In our simulations we considered up to three causal variants in cis, and evaluated how well the top three Potential Sets recovered all causal variants (Figure 2—figure supplements 13-15; Figure 2—figure supplement 15). We also reported the frequency of variant matches between Top and Stable PICS stratified by the number of causal variants simulated in Supplementary File 2B and 2C. Note Supplementary File 2C is for results from SuSiE fine-mapping; see Response to Reviewer 1, Comment 2.

Supplementary File 2B. Frequencies with which Stable and Top PICS have matching variants for the same potential set. For each SNR/ “No. Causal Variants” scenario, the number of matching variants is reported in parentheses.

Supplementary File 2C. Frequencies with which Stable and Top SuSiE have matching variants for the same credible set. For each SNR/ “No. Causal Variants” scenario, the number of matching variants is reported in parentheses.

(4) Relatedly, I wonder what fraction of non-matching variants are due to the lack of multiple causal variant modeling.

PICS handles multiple causal variants by including more potential sets to return, owing to the important caveat that causal variants in high LD cannot be statistically distinguished. For example, if one believes there are three causal variants that are not too tightly linked, one could make PICS return three potential sets rather than just one. To answer the question using our simulation study, we subsetted our results to just scenarios where the top and stable variants do not match. This mimics the exact scenario of having modeled multiple causal variants but still not yielding matching variants, so we can investigate whether these non-matching variants are in fact enriched in the true causal variants.

Because we expect causal variants to appear in some potential set, we specifically considered whether these non-matching causal variants might match along different potential sets across the different methods. In other words, we compared the stable variant with the top variant from another potential set for the other approach (e.g., Stable PICS Potential Set 1 variant vs Top PICS Potential Set 2 variant). First, we computed the frequency with which such pairs of variants match. A high frequency would demonstrate that, even if the corresponding potential sets do not have a variant match, there could still be a match between non-corresponding potential sets across the two approaches, which shows that multiple causal variant modeling boosts identification of matching variants between both approaches — regardless of whether the matching variant is in fact causal.

Low frequencies were observed. For example, when restricting to simulations where Top and Stable PICS Potential Set 1 variants did not match, about 2-3% of variants matched between the Potential Set 1 variant in Stable PICS and Potential Sets 2 and 3 variants in Top PICS; or between the Potential Set 1 variant in Top PICS and Potential Sets 2 and 3 variants in Stable PICS (Supplementary File 2D). When looking at non-matching Potential Set 2 or Potential Set 3 variants, we do see an increase in matching frequencies (between 10-20%) between Potential Set 2 variants and other potential set variants between the different approaches. However, these percentages are still small compared to the matching frequencies we observed between corresponding potential sets (e.g., for simulations with one causal variant this was 70-90% between Top and Stable PICS Potential Set 1, and for simulations with two and three causal variants this was 55-78% and 57-79% respectively).

We next checked whether these “off-diagonal” matching variants corresponded to the true causal variants simulated. Here we find that the causal variant recovery rate is mostly less than the corresponding rate for diagonally matching variants, which together with the low matching frequency suggests that the enrichment of causal variants of “off-diagonal” matching variants is much weaker than in the diagonally matching approach. In other words, the fraction of non-matching (causal) variants due to the lack of multiple causal variant modeling is low.

We discuss these findings in Supplementary File 1 Section S2 (bottom of p.2).

(5) I wonder if you can combine the stability-based and the residualization-based approach, i.e., using the residualized phenotypes for the stability-based approach. Would that further improve the accuracy or not?

This is a good idea, thank you for suggesting it. We pursued this combined approach on simulated gene expression phenotypes, but did not observe significant gains in causal variant recovery (Figure 2B; Figure 2—figure supplements 2, 13 and 15). We reported this Results “Searching for matching variants between Top PICS and Stable PICS improves causal variant Recovery.”

“We thus explore ways to combine the residualization and stability-driven approaches, by considering (i) combining them into a single fine-mapping algorithm (we call the resulting procedure Combined PICS); and (ii) prioritizing matching variants between the two algorithms. Comparing the performance of Combined PICS against both Top and Stable PICS, however, we find no significant difference in its ability to recover causal variants (Figure 2B)...”

However, we also confirmed in our simulations that prioritizing matching variants between the two approaches led to gains in causal variant recovery (Figure 2D; Figure 2—figure supplements 4, 19, 20 and 22). We reported this Results “Searching for matching variants between Top PICS and Stable PICS improves causal variant Recovery.”

“On the other hand, matching variants between Top and Stable PICS are significantly more likely to be causal. Across all simulations, a matching variant in Potential Set 1 is 2.5X as likely to be causal than either a non-matching top or stable variant (Figure 2D) — a result that was qualitatively consistent even when we stratified simulations by SNR and number of causal variants simulated (Figure 2—figure supplements 19, 20 and 22)...”

This finding is consistent with our analysis of real GEUVADIS gene expression data, where we reported larger functional significance of matching variants relative to non-matching variants returned by either Top of Stable PICS.

(6) The authors state that confounding in cohorts with diverse ancestries poses potential difficulties in identifying the correct causal variants. However, I don't see that they directly address whether the stability approach is mitigating this. It is hard to say whether the stability approach is helping beyond what simpler post-hoc QC (e.g., thresholding) can do.

Thank you for raising this fair point. Here is a model we have in mind. Gene expression phenotypes (Y) can be explained by both genotypic effects (G, as in genotypic allelic dosage) and the environment (E): Y = G + E. However, both G and E depend on ancestry (A), so that Y = G|A+E|A. Suppose that the causal variants are shared across ancestries, so that (G|A=a)=G for all ancestries a. Suppose however that environments are heterogeneous by ancestry: (E|A=a) = e(a) for some function e that depends non-trivially on a. This would violate the exchangeability of exogenous E in the full sample, but by performing fine-mapping on each ancestry stratum, the exchangeability of exogenous E is preserved. This provides theoretical justification for the stability approach.

We next turned to simulations, where we investigated 1,440 simulated gene expression phenotypes capturing various ways in which ancestry induces heterogeneity in the exogenous E variable (simulation details in Lines 576-610 of Materials and Methods). We ran Stable PICS, as well as a version of PICS that did not residualize phenotypes or apply the stability principle. We observed that (i) causal variant recovery performance was not significantly different between the two approaches (Figure 2—figure supplements 24-32); but (ii) disagreement between the approaches can be considerable, especially when the signal-to-noise ratio is low (Supplementary File 2A). For example, in a set of simulations with three causal variants, with SNR = 0.11 and E heterogeneous by ancestry by letting E be drawn from N(2σ,σ<sup>2</sup>) for only GBR individuals (rest are N(0,σ<sup>2</sup>)), there was disagreement between Potential Set 1 and 2 variants in 25% of simulations — though recovery rates were similar (Probability of recovering at least one causal variant: 75% for Plain PICS and 80% for Stable PICS). These points suggest that confounding in cohorts can reduce power in methods not adjusting or accounting for ancestral heterogeneity, but can be remedied by approaches that do so. We report this analysis in Results “Simulations justify exploration of stability guidance”

In the current version of our work, we have evaluated, using both simulations and empirical evidence, different ways to combine approaches to boost causal variant recovery. Our simulation study shows that prioritizing matching variants across multiple methods improves causal variant recovery. On GEUVADIS data, where we might not know which variants are causal, we already demonstrated that matching variants are enriched for functional annotations. Therefore, our analyses justify that the adverse consequence of confounding on reducing fine-mapping accuracy can be mitigated by prioritizing matching variants between algorithms including those that account for stability.

(7) For non-matching variants, I wonder what the difference of posterior probabilities is between the stable and top variants in each method. If the difference is small, maybe it is due to noise rather than signal.

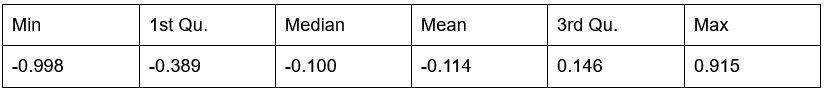

We have reported differences in posterior probabilities returned by Stable and Top PICS for GEUVADIS data; see Figure 3—figure supplement 1. For completeness, we compute the differences in posterior probabilities and summarize these differences both as histograms and as numerical summary statistics.

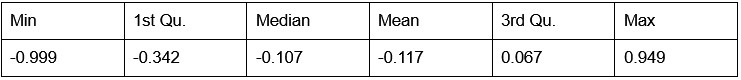

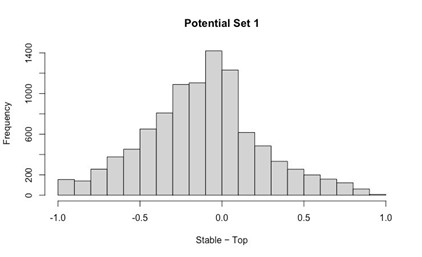

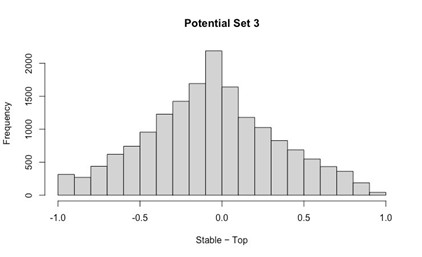

Potential Set 1

- Number of non-matching variants = 9,921

- Table of Summary Statistics of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response table 1.

- Histogram of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response image 1.

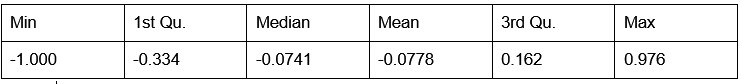

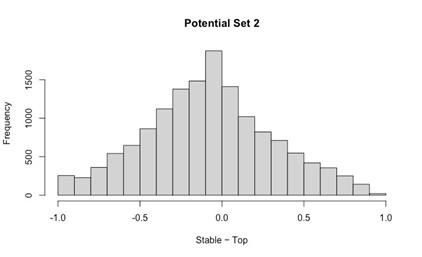

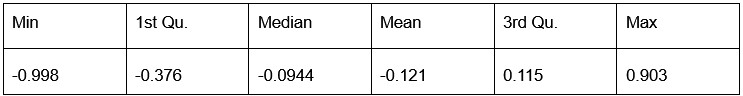

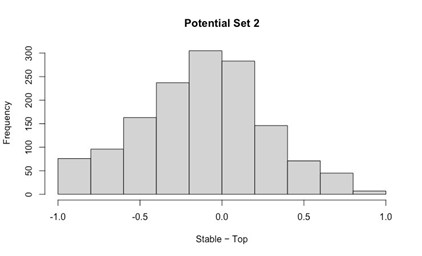

Potential Set 2

- Number of non-matching variants = 14,454

- Table of Summary Statistics of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response table 2.

- Histogram of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response image 2.

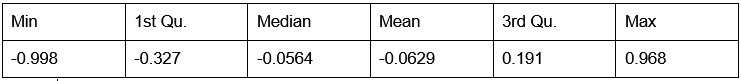

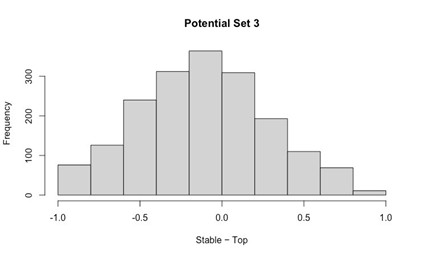

Potential Set 3

- Number of non-matching variants = 16,814

- Table of Summary Statistics of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response table 3.

- Histogram of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response image 3.

We also compared the difference in posterior probabilities between non-matching variants returned by Stable PICS and Top PICS for our 2,400 simulated gene expression phenotypes. Focusing on just Potential Set 1 variants, we find two equally likely scenarios, as demonstrated by two distinct clusters of points in a “posterior probability-posterior probability” plot. The first is, as pointed out, a small difference in posterior probability (points lying close to y=x). The second, however, reveals stable variants with very small posterior probability (of order 4 x 10<sup>–5</sup> to 0.05) but with a non-matching top variant taking on posterior probability well distributed along [0,1]. Moving down to Potential Sets 2 and 3, the distribution of pairs of posterior probabilities appears less clustered, indicating less tendency for posterior probability differences to be small ( Figure 2—figure supplement 8).

Here are the histograms and numerical summary statistics.

Potential Set 1

- Number of non-matching variants = 663 (out of 2,400)

- Table of Summary Statistics of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response table 4.

- Histogram of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response image 4.

Potential Set 2

Number of non-matching variants = 1,429 (out of 2,400)

- Table of Summary Statistics of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response table 5.

- Histogram of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response image 5.

Potential Set 3

- Number of non-matching variants = 1,810 (out of 2,400)

- Table of Summary Statistics of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response table 6.

- Histogram of (Stable Posterior Probability – Top Posterior Probability)

Author response image 6.

(8) It's a bit surprising that you observed matching variants with (stable) posterior probability ~ 0 (SFig. 1). What are the interpretations for these variants? Do you observe functional enrichment even for low posterior probability matching variants?

Thank you for this question. We have performed a thorough analysis of matching variants with very low stable posterior probability, which we define as having a posterior probability < 0.01 (Supplementary File 1 Section S11). Here, we briefly summarize the analysis and key findings.

Analysis

First, such variants occur very rarely — only 8 across all three potential sets in simulations, and 17 across all three potential sets for GEUVADIS (the latter variants are listed in Supplementary 2E). We begin interpreting these variants by looking at allele frequency heterogeneity by ancestry, support size — defined as the number of variants with positive posterior probability in the ALL slice* — and the number of slices including the stable variant (i.e., the stable variant reported positive posterior probability for the slice).

*Note that the stable variant posterior probability need not be at least 1/(Support Size). This is because the algorithm may have picked a SNP that has a lower posterior probability in the ALL slice (i.e., not the top variant) but happens to appear in the most number of other slices (i.e., a stable variant).

For variants arising from simulations, because we know the true causal variants, we check if these variants are causal. For GEUVADIS fine-mapped variants, we rely on functional annotations to compare their relative enrichment against other matching variants that did not have very low stable posterior probability.

Findings

While we caution against generalizing from observations reported here, which are based on very small sample sizes, we noticed the following. In simulations, matching variants with very low stable posterior probability are largely depleted in causal variants, although factors such as the number of slices including the stable variant may still be useful. In GEUVADIS, however, these variants can still be functionally enriched. We reported three examples in Supplementary File 1 Section S11 (pp. 8-9 of Supplement), where the variants were enriched in either VEP or biologically interpretable functional annotations, and were also reported in earlier studies. We partially reproduce our report below for convenience.

“However, we occasionally found variants that stand out for having large functional annotation scores. We list one below for each potential set.

- Potential Set 1 reported the variant rs12224894 from fine-mapping ENSG00000255284.1 (accession code AP006621.3) in Chromosome 11. This variant stood out for lying in the promoter flanking region of multiple cell types and being relatively enriched for GC content with a 75bp flanking region. This variant has been reported as a cis eQTL for AP006632 (using whole blood gene expression, rather than lymphoblastoid cell line gene expression in this study) in a clinical trial study of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (Davenport et al., 2018). Its nearest gene is GATD1, a ubiquitously expressed gene that codes for a protein and is predicted to regulate enzymatic and catabolic activity. This variant appeared in all 6 slices, with a moderate support size of 23.

- Potential Set 2 reported the variant rs9912201 from fine-mapping ENSG00000108592.9 (mapped to FTSJ3) in Chromosome 17. Its FIRE score is 0.976, which is close to the maximum FIRE score reported across all Potential Set 2 matching variants. This variant has been reported as a SNP in high LD to a GWAS hit SNP rs7223966 in a pan-cancer study (Gong et al., 2018). This variant appeared in all 6 slices, with a moderate support size of 32.

- Potential Set 3 reported the variant rs625750 from fine-mapping ENSG00000254614.1 (mapped to CAPN1-AS1, an RNA gene) in Chromosome 11. Its FIRE score is 0.971 and its B statistic is 0.405 (region under selection), which lie at the extreme quantiles of the distributions of these scores for Potential Set 3 matching variants with stable posterior probability at least 0.01. Its associated mutation has been predicted to affect transcription factor binding, as computed using several position weight matrices (Kheradpour and Kellis, 2014). This variant appeared in just 3 slices, possibly owing to the considerable allele frequency difference between ancestries (maximum AF difference = 0.22). However, it has a small support size of 4 and a moderately high Top PICS posterior probability of 0.64.

To summarize, our analysis of GEUVADIS fine-mapped variants demonstrates that matching variants with very low stable posterior probability could still be functionally important, even for lower potential sets, conditional on supportive scores in interpretable features such as the number of slices containing the stable variant and the posterior probability support size…”

-

-

iowastatedaily.com iowastatedaily.com

-

“Digital badges are a great opportunity for Iowa State students to explore different avenues to build career-readiness skills,” Hageman said. “It’s not just a badge, it’s the work you put into earning it that stands out.”

Student quote

-

-

www.windowscentral.com www.windowscentral.com

-

Hundreds of millions of us have already given away ownership over music, TV shows, and movies to cloud companies like Spotify and Netflix — both of which run on Amazon Web Services. Cloud gaming products like Amazon Luna, NVIDIA GeForce Now, and Xbox Cloud Gaming are all seeing steady growth, too — but it's not just about these niche scenarios.

fair point, we do need to bring media home again. i've made the switch in books early last year. Music up next.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

olitics and the New Machine

The core argument

The essay argues that polling has become less reliable at the same time that it has become more powerful, and that this combination distorts democratic politics.

Polls:

increasingly fail to accurately measure public opinion

yet increasingly determine who gets attention, legitimacy, money, debate access, and media coverage

How Trump fits in

The piece opens with Donald Trump claiming he has no pollster and doesn’t tailor his message to polls. Lepore calls this disingenuous:

Trump may not have had a traditional campaign pollster

but his rise depended heavily on polls for visibility and validation

polls got him into debates, dictated stage placement, and fueled media coverage

So Trump is described as “a creature of the Sea of Polls,” not above it

Why modern polls are broken

The article explains in detail why polling has deteriorated:

- People don’t answer anymore

Response rates used to be 60–90%

Now they’re often in the single digits

Most Americans refuse poll calls, creating non-response bias

- Technology & law made it worse

Fewer landlines

Cell-phone autodialing is illegal

Internet polls are self-selected and skew younger and more liberal

Mixed-method polling still doesn’t work well

- Samples are tiny and fragile

National election polls often rely on ~1,000–2,000 people

Statistical “weighting” tries to fix bias, but the lower the response rate, the shakier the results

Why polls now matter more than ever

Despite being unreliable, polls are used to:

decide who qualifies for debates

determine media attention

shape fundraising and momentum

create “winners” and “losers” long before anyone votes

Fox News using polls to select debate participants is presented as a major example of polling replacing democratic processes.

Historical background

The essay gives a history of polling:

Early “straw polls” by newspapers

The rise of George Gallup in the 1930s

Polling claimed to represent “the will of the people” scientifically

But:

Early polls systematically excluded Black Americans, the poor, and the disenfranchised

Polling mirrored and amplified existing inequalities

What was presented as “public opinion” was often the opinion of a privileged subset

Deeper philosophical critique

Lepore raises a fundamental question:

What if measuring public opinion isn’t good for democracy at all?

Key ideas:

Polls treat public opinion as the sum of individual answers, ignoring how opinions are formed socially

Polls can create opinion rather than measure it

Constant polling shifts politics from deliberation and leadership to reacting to numbers

Bottom line

The piece isn’t just saying “polls are inaccurate.”

It’s saying:

Polls shape reality instead of describing it

They weaken representative democracy

They reward spectacle, momentum, and media attention over governance

And they increasingly substitute statistical artifacts for actual voting

-

-

publish.obsidian.md publish.obsidian.md

-

Weapons made of obsidian, jewelry crafted from jade

Obsidian often is known for protecting you against negative energies and psychic attacks in some religions, besides it being a sharp volcanic glass that can easily pierce victims of its wrath. It's also good for grounding you, or in other words, just keeping you in check with reality. As for jade, it can have several benefits in some cultures depending on the color. For example, green jade (usually seen in bangle form in countries like Vietnam and Myanmar/Burma) can represent wealth and luck. Just wanted to share because I am a massive fan of geology and crystal identification.

-

-

biz.libretexts.org biz.libretexts.org

-

The assumption that women are more relationship oriented, while men are more assertive, is an example of a stereotype.

How’s this stereotype LMAO. It’s just a fact of biological reality

-

-

social-media-ethics-automation.github.io social-media-ethics-automation.github.io

-

While this example is not on social media, I think that something similar is our use of plastic in our everyday lives. On the surface, it's just a bottle of water or a bag of chips, but the reality is that plastic has now permeated into our lives at a microscopic scale.

-

-

social-media-ethics-automation.github.io social-media-ethics-automation.github.io

-

In this screenshot of Twitter, we can see the following information: The account that posted it: User handle is @dog_rates User name is WeRateDogs® User profile picture is a circular photo of a white dog This user has a blue checkmark The date of the tweet: Feb 10, 2020 The text of the tweet: “This is Woods. He’s here to help with the dishes. Specifically, the pre-rinse, where he licks every item he can. 12/10” The photos in the tweet: Three photos of a puppy on a dishwasher The number of replies: 1,533 The number of retweets: 26.2K The number of likes: 197.8K

This gives a brief information of the user's information, the data such as likes and comments gives a brief idea that is this content worth to pay a close reading or not. Clearly this example is worthy! Also just one post it contains soo many information, it's kind of surprising.

-

-

social-media-ethics-automation.github.io social-media-ethics-automation.github.io

-

If we download information about a set of tweets (text, user, time, etc.) to analyze later, we might consider that set of information as the main data, and our metadata might be information about our download process, such as when we collected the tweet information, which search term we used to find it, etc.

I never realized how powerful metadata can be. It’s interesting that it’s not just about the content of the tweets, but also about information like when and how we collected them. That extra layer can really change how we understand and analyze data. It can reveal what time someone does things, trends, and behavior that we don't see behind the scenes.

-

-

social-media-ethics-automation.github.io social-media-ethics-automation.github.io

-

Images are created by defining a grid of dots, called pixels. Each pixel has three numbers that define the color (red, green, and blue), and the grid is created as a list (rows) of lists (columns).

It’s cool to see how images are really just grids of pixels with RGB values, and even something like microRGB fits into that same idea of breaking color down into tiny components. Thinking about images this way makes them feel a lot less mysterious and more like something you can actually work with in code.

-

Sounds are represented as the electric current needed to move a speaker’s diaphragm back and forth over time to make the specific sound waves. The electric current is saved as a number, and those electric current numbers are saved at each time point, so the sound information is saved as a list of numbers.

It’s interesting to think about how sound is really just a list of numbers that tell a speaker how to move, moment by moment, to recreate a noise or a voice. Once you see it that way, audio feels a lot less abstract and more like something you can store, edit, and mess with just like any other data.

-

Images are created by defining a grid of dots, called pixels. Each pixel has three numbers that define the color (red, green, and blue), and the grid is created as a list (rows) of lists (columns).

I've heard only three colors (RGB) are needed because these colors are enough to recreate what the human eye perceives. I think it’s interesting how such a wide range of colors and detailed images can be created just by changing the intensity of three simple values in each pixel.

-

-

social-media-ethics-automation.github.io social-media-ethics-automation.github.io

-

In our example tweet we can see several places where data could be saved in lists:

This section makes it click that a “tweet” isn’t just one thing—it’s basically a bundle of lists (a list of images, a list of likes, a list of replies, etc.). Thinking of it that way also helps explain why social media data gets huge fast, because each post can point to multiple growing lists. It’s kind of wild that even something simple like “who liked this” is literally stored as a list of accounts behind the scenes.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Note: This preprint has been reviewed by subject experts for Review Commons. Content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Referee #1

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

Summary:

This study by Neupane et al. investigates modulators of α-synuclein aggregation, focusing on Ser129-phosphorylated α-synuclein (pSyn129), a pathological hallmark of Parkinson's disease (PD). The authors performed high-content image-based, arrayed CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and knockout (CRISPRo) screens targeting > 2300 genes related to mitochondrial function, intracellular trafficking, and cytoskeletal reorganization. Using α-Syn overexpressing HEK293 cells, they identified OXR1 and EMC4 as novel modulators of pSyn129 abundance. Key findings were that activation of the mitochondrial protein OXR1 increased pSyn129 by decreasing ATP levels, while ablation of the ER-associated protein EMC4 reduced pSyn129 by enhancing autophagic flux and lysosomal clearance. These findings were validated in human iPSC-derived cortical and dopaminergic neurons.

My major comments have to do with statistical methods and with significance of their findings.

Major comments:

Are the claims and the conclusions supported by the data or do they require additional experiments or analyses to support them?

The claims and conclusions are generally well-supported by the presented data. The dual CRISPRa/CRISPRo screen provides a robust initial discovery platform, and the validation in iPSC-derived neurons strengthens the findings and their translational relevance. The mechanistic insights into OXR1 (ATP levels) and EMC4 (autophagic flux, lysosomal clearance) are supported by the described experiments. The use of two antibodies (81A and EP1536Y) for pSyn129 also enhances confidence in the measurements. I had a few questions about the statistical methods. The main concern I have about methodology for the screen is whether the authors have corrected for multiple hypotheses in their discovery screen. This is not clear from the text, methods, or legends (for Figures 2A/2B/2C).

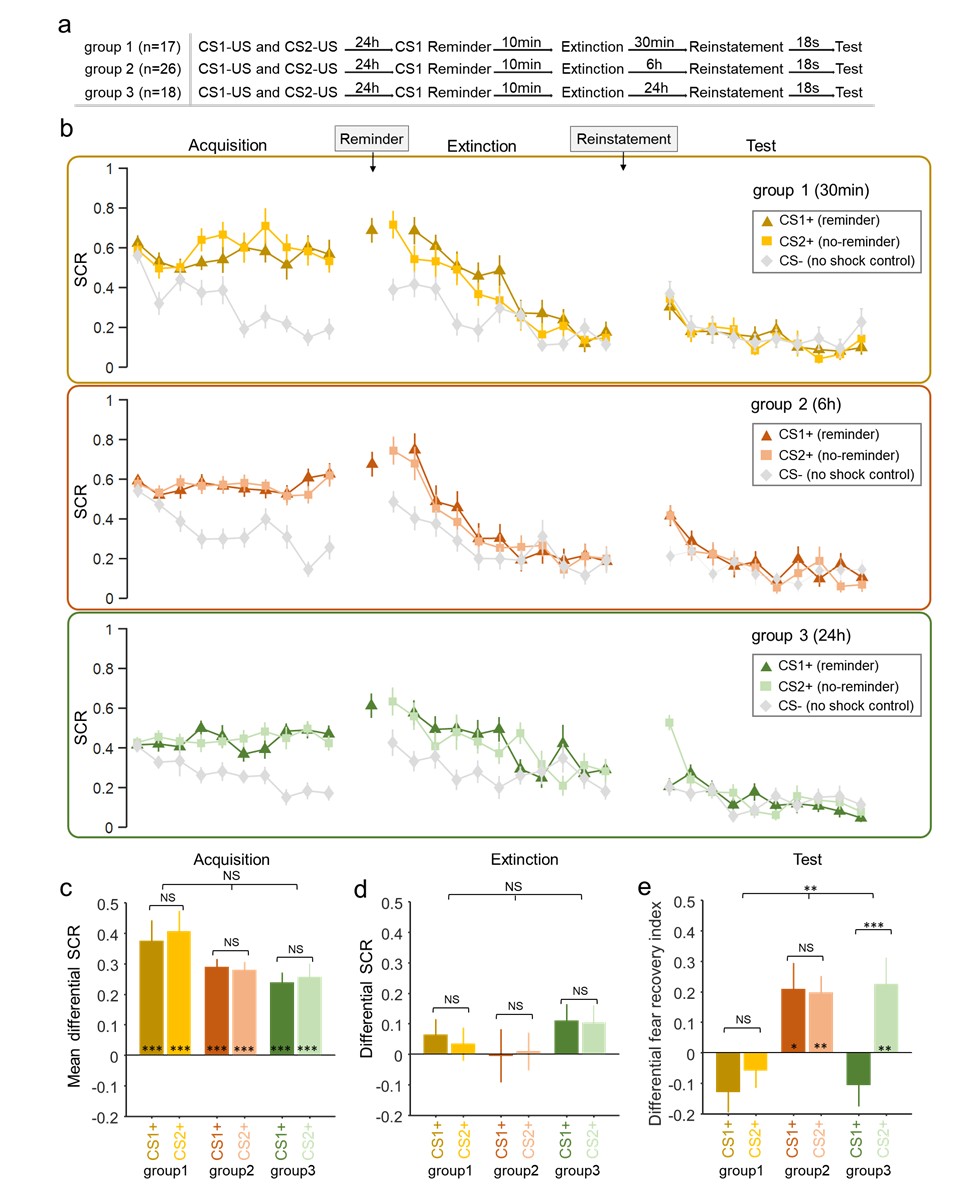

- Figure 1B suggests a very large range of activation (multiple orders of magnitude) in the initial screen. What is the relationship between level of expression change and functional effect across the screen? How upregulated/downregulated are OXR1 and EMC4 at the mRNA and protein levels?

- Supplemental Figure S2D: Why do the non-targeting controls differ from the majority of the CRISPRa genes? If I am reading the figure correctly, it seems strange that the vast majority of the CRISPRa gene targets reduces pSyn pathology relative to the non-targeting controls (which is why I am wondering whether the level of increased expression correlates with the level of functional effect).

- In Figure 2A/B/C, is the p-value adjusted in any way for multiple comparisons? If so, this should be indicated in the legend. If not, why not? (The potential for false positives in a screen is very large and requires correction for multiple comparisons.)

- Figure 3: It's interesting that different seeding materials have different effects. However, it's quite surprising that the authors find less seeding with MSA-derived material in both the CRISPRa and CRISPRo context. This contradicts the work of Peng and coauthors (PMID 29743672) who find that MSA-derived material is much more potent in seeding aggregates in a number of different cell types. Do the authors have any thoughts about why this is the case?

- Figure 7A: pSyn129 image in the non-targeting control is poor - the very bright dots look like artifact. Not clear why the authors don't corroborate with EP1536Y antibody as they do in Figure 5.

- Overall methodology: Are the pSyn inclusions soluble? This could be easily determined by performing 1% TritonX extraction, for example, and it helps us understand how "pathological" the inclusions are.

- OPTIONAL: The authors perform some interesting experiments looking at genes affected downstream by, for example, OXR1 over-expression. It would be useful to understand whether the upstream effect is dependent on downstream effect. This could be tested by performing double perturbations (e.g. OXR1 overexpression and CCL8 knockout or ALDOC upregulation).

- OPTIONAL: The link between EMC4 ablation and enhanced ER-driven autophagic flux/lysosomal clearance could be corroborated with additional experiments. E.g.: Does EMC4 normally inhibit this pathway? Or only in the context of aSyn fibril seeding?

Are the suggested experiments realistic in terms of time and resources?

The OPTIONAL experiments are generally feasible as they employ methods that the lab is already using in this paper.

Are the experiments adequately replicated and statistical analysis adequate?

See comment about multiple hypothesis testing above.

Significance

This is a well-designed, difficult-to-accomplish study that expands the landscape of pS129Syn modulators. The validation of the primary hits identified in HEK293 cells in iPSC-derived neurons gives the findings greater relevance.

Strengths:

- Novelty: Using an unbiased and high-throughput approach, the study identifies two novel regulators of α-Syn aggregation, namely OXR1 and EMC4.

- Methodological Rigor: The use of arrayed CRISPRa/CRISPRo screens with high-content imaging is powerful and difficult to accomplish. Methodologically, this is a tour de force.

- Orthogonal Validation: The use of multiple α-Syn fibril polymorphs/strains and different antibodies (81A, EP1536Y) strengthens the robustness of the findings.

Limitations:

- It's not clear to me that pSyn129 is the ultimate readout. At a minimum, we should know something about the solubility of the inclusions. Some panels (e.g. Figure 7A) are not very informative in terms of what the authors are calling pSyn129+.

- The study relies on in vitro cellular models. While iPSC-derived neurons are relevant, the complexity of the brain environment, including glial cell interactions is not fully captured. This is fine for an initial report, but it does limit the significance.

- OXR1 and EMC4 seem to be very generic modulators. It's not clear to me that their effects are specific to aSyn or to PD in any way - they might just be effects on very basic cellular functions that would be applicable to a number of stressors or proteinopathies. Maybe that is fine (we probably need to get rid of tau aggregates, too!), but I don't think the authors can claim that they have identified "organelle-specific genetic nodes of aSyn pathology" since they biased their screen towards mitochondria and they don't test any other pathological aggregates. Moreover, from a translational perspective, it's not clear to me that implicating the antioxidant pathway or lysosomal/autophagosomal pathways in the pathogenesis of PD is new, and it's not clear that the specific genes identified would make good therapeutic targets.

-

-

social-media-ethics-automation.github.io social-media-ethics-automation.github.io

-

Examples of Bots

The section on antagonistic bots was especially interesting to me. It’s concerning how bots can create the illusion of mass support or backlash, even when most real users don’t feel that strongly. This makes me think that bots don’t just add noise, but can actually change how people interpret public opinion.

-

We also would like to point out that there are fake bots as well, that is real people pretending their work is the result of a Bot. For example, TikTok user Curt Skelton posted a video claiming that he was actually an AI-generated / deepfake character:

As someone who's majoring in a creative field, I find it both incredibly interesting and concerning just how advanced AI is getting, and where this rapid innovation will take us in just a few years. It's so jarring to be watching a video on Tiktok or Instagram and fully believe it to be completely real, just to feel the need to dissect the video to see if it's really real. I can't begin to imagine how the job industry will change due to AI, but with innovation there (hopefully) comes opportunity.**

-

-

social-media-ethics-automation.github.io social-media-ethics-automation.github.io

-

I think that tech giants are not invested in ethical changes because there is no real risk for them. At the end of the day, the goal is to make more money for shareholders, and if the well-being of users is not going to make them money, then it is not worth investing in. I believe that technology can be regulated at the same speed as its advancement. It's just, regulation will put up barriers to profit, so instead surface-level ethics are presented to us as a bandaid to ethical issues that are growing like a cancer at the same rate technology is advancing.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

In neoclassical and neoliberal economics, state spendingon services is framed as being paid for by the “productive” –i.e. profitable – sector of the economy. But, as we learned inthe pandemic, the most useful and essential parts of our soci-ety are often the least profitable and their workers the leastremunerated. Many profitable sectors are not useful, andoften quite damaging. Large parts of the hyper-profitablefinance sector are parasitic on the public service sector. AsI argued in Chapter 2, this “productive” economy relies on awhole set of disavowed systems – education, domestic labour,environment – without which its profits would be impossible.

I feel this argument, against bullshit jobs, is much stronger than "capitalism has failed"... for once, because it doesn't necessitate a defeatist starting point, and can me framed as even a satirical position (CEOs don't do crap, is laughable), and for second, because just world hypothesis conservatism bias tells people this can't be the case. Messages online tell people "capitalism+democracy" is the way to go, or else dictatorships by the ultra rich (?). I find it amusing, that more of the same sells so nicely, but that's what people see, survivorship bias big companies employing lots of people, and capitalism lifting out pop stars through financial mobility, and the system delivering all the goods we can possible think of. It's become spectacular consumerism, and culture is everywhere. Culture works, it fucking does, but not your culture, rather Gmail's, and Meta, and OnlyFans, Roblox, etc. one.

-

Health, education,housing, transport, food, energy, water, basic communicationsystems – should these not be fixed before we get to culture?1In what follows I make an argument for the centrality ofculture in overcoming the present crisis, and in the followingchapters sketch out what such an agenda might look like. Weneed to acknowledge the “legitimation crisis” to which culture-as- industry was a response – art associated with elitism andpatrician subsidy, the growth of the culture industries

But culture is health! A culture of health, of dancing, of being engaged in mentally challenging projects. Culture is education, it teaches, it creates communities. Culture might not be food per se, but it can help grow food, and cook it, collectively, with shared non-contaminating gardens, and recycling processes, through rites more often depicted in religion.

Culture is communication when misscomunication is rampant: It's not just posting and sharing the life of your children online, it's being aware of its impacts, checking before sending news, and feeling safe enough to talk about suicide and emotions, or to speak up about a close relative who is harassing you, regardless of gender! Is this not a progressivist culture that does not invisibilise these things to private life?

Or rather, arguably, culture could act as these things. Currently, mass consumption culture is at times an inhibating mass-sterelisation device, and at others, a way to propagate neo-colonialist monopolistic ideals who benefit a wealthy few. It also perpetuates the myth of equality and meritocracy, through ads, and its instrumentalist tokenised portrayal of diverse hires and rampant on your face corruption and ideals buying, ultimately makes change within the system almost impossible.

-

Neoliberalism, a distinct phase of global capitalism thatemerged in the early 1980s, is in crisis. The economic, politi-cal, and social solutions it brought to the prior crisis of Fordistsocial democracy in the 1970s no longer work. That muchmight be broadly agreed. It has become ever clearer since the2008– 10 global financial crisis. Stagnant growth, stalled wages,growing inequality, cost- of-living increases, rising indebtedness,increasing precarity of employment, and the erosion of publicservices are the stuff of the nightly news. This is accompaniedby widespread disaffection and disconnection from the politicalprocess, resulting in alternating moments of political efferves-cence (often as anti-politics) and resigned passivity. This in theface of a growing perception of the deepening hold of powerfulelites over the workings of government, in the form of lobby-ing, political finance, corruption, cronyism, the public–private“revolving door”, and a pervasive cynicism towards techno-cratic political expertise

Yes, but there have been some welfare and rights advances! Think women and LGBTIQA+ rights. There is increasing cost because demographics have changed, it's not just automation and IA giving the capitalists excess capital gains. Polarisation and corruption are a byproduct of mass production, of noisy, post-truth production.

-

-

www.bitbybitbook.com www.bitbybitbook.com

-

The “Internet of Things” means that behavior in the physical world will be increasingly captured by digital sensors. In other words, when you think about social research in the digital age you should not just think online, you should think everywhere.

In my Intro to Information class, I recall my professor discussing the substantial impact that many researchers deem AI to have — an impact that is only comparable to that of the introduction of the Internet. It makes me think about how revolutionary AI feels to be in the midst of its development and how I often overlook this scale when thinking about the internet simply because it's all I've known throughout my upbringing. The digitization and automation of many once manual processes is so commonplace now, I can only imagine how much it'll change in the upcoming years

-

-

socialsci.libretexts.org socialsci.libretexts.org

-

All of these problems indicate that older people should be less happy than younger people. If a sociologist did some research and then reported that older people are indeed less happy than younger people, what have we learned?

I only believe something when there is a hypothesis tested many times and the prediction comes true. Many old people get sick and struggle because they did not take care of themselves when they were young and used different things that made their bodies weak. My point is we can’t just keep predicting things. If we keep predicting, it’s just assuming about things we’re not really sure of yet.

-

Sociology can help us understand the social forces that affect our behavior, beliefs, and life chances, but it can only go so far. That limitation conceded, sociological understanding can still go fairly far toward such an understanding, and it can help us comprehend who we are and what we are by helping us first understand the profound yet often subtle influence of our social backgrounds on so many things about us.

When I first got here in America, there were certain things I believed because of my social background. My husband had a therapist, so I joined his therapy. At first, I just listened to other people’s problems and issues, until the therapist asked me about my own feelings about my family. I had a lot of beliefs like ‘my family is great,’ but when he asked me, I felt doomed because I didn’t know what to say and I didn’t even know the definition of feelings. As we kept working, I started to see the reality. I saw the true color, the true image of my past. I realized I have a lot of trauma, but at least now I can face it. I can see it is there, instead of lying to myself that it is not there. I know it’s not perfect and I still have a lot of issues and a lot of scramble in my life, but at least I can work on it now.

-

-

nmoer.pressbooks.pub nmoer.pressbooks.pub

-

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Florida, I didn’t understand that each academic discipline I took courses in to complete the requirements of my degree (history, philosophy, biology, math, political science, sociology, English) was a different discourse community. Each of these academic fields had their own goals, their own genres, their own writing conventions, their own formats for citing sources, and their own expectations for writing style. I thought each of the teachers I encountered in my undergraduate career just had their own personal preferences that all felt pretty random to me. I didn’t understand that each teacher was trying to act as a representative of the discourse community of their field.

Discipline is and always will be part of any professional or academic career, personally I think that if you want to be successful you have to be organized and disciplined. If I feel it's more challenging, it's because it will help me push myself and see what I'm capable of and how I handle situations under pressure.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors present a novel usage of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) to measure NAD(P)H autofluorescence in the Drosophila brain, as a proxy for cellular metabolic/redox states. This new method relies on the fact that both NADH and NADPH are autofluorescent, with a different excitation lifetime depending on whether they are free (indicating glycolysis) or protein-bound (indicating oxidative phosphorylation). The authors successfully use this method in Drosophila to measure changes in metabolic activity across different areas of the fly brain, with a particular focus on the main center for associative memory: the mushroom body.

Strengths:

The authors have made a commendable effort to explain the technical aspects of the method in accessible language. This clarity will benefit both non-experts seeking to understand the methodology and researchers interested in applying FLIM to Drosophila in other contexts.

Weaknesses:

(1) Despite being statistically significant, the learning-induced change in f-free in α/β Kenyon cells is minimal (a decrease from 0.76 to 0.73, with a high variability). The authors should provide justification for why they believe this small effect represents a meaningful shift in neuronal metabolic state.

We agree with the reviewer that the observed f_free shift averaged per individual, while statistically significant, is small. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate a physiological (i.e., not pharmacologically induced) variation in neuronal metabolism using FLIM. As such, there are no established expectations regarding the amplitude of the effect. In the revised manuscript, we have included an additional experiment involving the knockdown of ALAT in α/β Kenyon cells, which further supports our findings. We have also expanded the discussion to expose two potential reasons why this effect may appear modest.

(2) The lack of experiments examining the effects of long-term memory (after spaced or massed conditioning) seems like a missed opportunity. Such experiments could likely reveal more drastic changes in the metabolic profiles of KCs, as a consequence of memory consolidation processes.

We agree with the reviewer that investigating the effects of long-term memory on metabolism represent a valuable future path of investigation. An intrinsic caveat of autofluorescence measurement, however, is to identify the cellular origin of the observed changes. To this respect, long-term memory formation is not an ideal case study as its essential feature is expected to be a metabolic activation localized to Kenyon cells’ axons in the mushroom body vertical lobes (as shown in Comyn et al., 2024), where many different neuron subtypes send intricate processes. This is why we chose to first focus on middle-term memory, where changes at the level of the cell bodies could be expected from our previous work (Rabah et al., 2022). But our pioneer exploration of the applicability of NAD(P)H FLIM to brain metabolism monitoring in vivo now paves the way to extending it to the effect of other forms of memory.

(3) The discussion is mostly just a summary of the findings. It would be useful if the authors could discuss potential future applications of their method and new research questions that it could help address.

The discussion has been expanded by adding interpretations of the findings and remaining challenges.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This manuscript presents a compelling application of NAD(P)H fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) to study metabolic activity in the Drosophila brain. The authors reveal regional differences in oxidative and glycolytic metabolism, with a particular focus on the mushroom body, a key structure involved in associative learning and memory. In particular, they identify metabolic shifts in α/β Kenyon cells following classical conditioning, consistent with their established role in energy-demanding middle- and long-term memories.

These results highlight the potential of label-free FLIM for in-vivo neural circuit studies, providing a powerful complement to genetically encoded sensors. This study is well-conducted and employs rigorous analysis, including careful curve fitting and well-designed controls, to ensure the robustness of its findings. It should serve as a valuable technical reference for researchers interested in using FLIM to study neural metabolism in vivo. Overall, this work represents an important step in the application of FLIM to study the interactions between metabolic processes, neural activity, and cognitive function.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This study investigates the characteristics of the autofluorescence signal excited by 740 nm 2-photon excitation, in the range of 420-500 nm, across the Drosophila brain. The fluorescence lifetime (FL) appears bi-exponential, with a short 0.4 ns time constant followed by a longer decay. The lifetime decay and the resulting parameter fits vary across the brain. The resulting maps reveal anatomical landmarks, which simultaneous imaging of genetically encoded fluorescent proteins helps to identify. Past work has shown that the autofluorescence decay time course reflects the balance of the redox enzyme NAD(P)H vs. its protein-bound form. The ratio of free-to-bound NADPH is thought to indicate relative glycolysis vs. oxidative phosphorylation, and thus shifts in the free-to-bound ratio may indicate shifts in metabolic pathways. The basics of this measure have been demonstrated in other organisms, and this study is the first to use the FLIM module of the STELLARIS 8 FALCON microscope from Leica to measure autofluorescence lifetime in the brain of the fly. Methods include registering the brains of different flies to a common template and masking out anatomical regions of interest using fluorescence proteins.

The analysis relies on fitting an FL decay model with two free parameters, f_free and t_bound. F_free is the fraction of the normalized curve contributed by a decaying exponential with a time constant of 0.4 ns, thought to represent the FL of free NADPH or NADH, which apparently cannot be distinguished. T_bound is the time constant of the second exponential, with scalar amplitude = (1-f_free). The T_bound fit is thought to represent the decay time constant of protein-bound NADPH but can differ depending on the protein. The study shows that across the brain, T_bound can range from 0 to >5 ns, whereas f_free can range from 0.5 to 0.9 (Figure 1a). These methods appear to be solid, the full range of fits are reported, including maximum likelihood quality parameters, and can be benchmarks for future studies.

The authors measure the properties of NADPH-related autofluorescence of Kenyon Cells(KCs) of the fly mushroom body. The results from the three main figures are:

(1) Somata and calyx of mushroom bodies have a longer average tau_bound than other regions (Figure 1e);

(2) The f_free fit is higher for the calyx (input synapses) region than for KC somata (Figure 2b);

(3) The average across flies of average f_free fits in alpha/beta KC somata decreases from 0.734 to 0.718. Based on the first two findings, an accurate title would be "Autofluorecense lifetime imaging reveals regional differences in NADPH state in Drosophila mushroom bodies."

The third finding is the basis for the title of the paper and the support for this claim is unconvincing. First, the difference in alpha/beta f_free (p-value of 4.98E-2) is small compared to the measured difference in f_free between somas and calyces. It's smaller even than the difference in average soma f_free across datasets (Figure 2b vs c). The metric is also quite derived; first, the model is fit to each (binned) voxel, then the distribution across voxels is averaged and then averaged across flies. If the voxel distributions of f_free are similar to those shown in Supplementary Figure 2, then the actual f_free fits could range between 0.6-0.8. A more convincing statistical test might be to compare the distributions across voxels between alpha/beta vs alpha'/beta' vs. gamma KCs, perhaps with bootstrapping and including appropriate controls for multiple comparisons.

The difference observed is indeed modest relative to the variability of f_free measurements in other contexts. The fact that the difference observed between the somata region and the calyx is larger is not necessarily surprising. Indeed, these areas have different anatomical compositions that may result in different basal metabolic profiles. This is suggested by Figure 1b which shows that the cortex and neuropile have different metabolic signatures. Differences in average f_free values in the somata region can indeed be observed between naive and conditioned flies. However, all comparisons in the article were performed between groups of flies imaged within the same experimental batches, ensuring that external factors were largely controlled for. This absence of control makes it difficult to extract meaningful information from the comparison between naive and conditioned flies.

We agree with the reviewer that the choice of the metric was indeed not well justified in the first manuscript. In the new manuscript, we have tried to illustrate the reasons for this choice with the example of the comparison of f_free in alpha/beta neurons between unpaired and paired conditioning (Dataset 8). First, the idea of averaging across voxels is supported by the fact that the distributions of decay parameters within a single image are predominantly unimodal. Examples for Dataset 8 are now provided in the new Sup. Figure 14. Second, an interpretable comparison between multiple groups of distributions is, to our knowledge, not straightforward to implement. It is now discussed in Supplementary information. To measure interpretable differences in the shapes of the distributions we computed the first three moments of distributions of f_free for Dataset 8 and compared the values obtained between conditions (see Supplementary information and new Sup. Figure 15). Third, averaging across individuals allows to give each experimental subject the same weight in the comparisons.

I recommend the authors address two concerns. First, what degree of fluctuation in autofluorescence decay can we expect over time, e.g. over circadian cycles? That would be helpful in evaluating the magnitude of changes following conditioning. And second, if the authors think that metabolism shifts to OXPHOS over glycolosis, are there further genetic manipulations they could make? They test LDH knockdown in gamma KCs, why not knock it down in alpha/beta neurons? The prediction might be that if it prevents the shift to OXPHOS, the shift in f_free distribution in alpha/beta KCs would be attenuated. The extensive library of genetic reagents is an advantage of working with flies, but it comes with a higher standard for corroborating claims.

In the present study, we used control groups to account for broad fluctuations induced by external factors such as the circadian cycle. We agree with the reviewer that a detailed characterization of circadian variations in the decay parameters would be valuable for assessing the magnitude of conditioning-induced shifts. We have integrated this relevant suggestion in the Discussion. Conducting such an investigation lies unfortunately beyond the scope and means of the current project.

In line with the suggestion of the reviewer, we have included a new experiment to test the influence of the knockdown of ALAT on the conditioning-induced shift measured in alpha/beta neurons. This choice is motivated in the new manuscript. The obtained result shows that no shift is detected in the mutant flies, in accordance with our hypothesis.

FLIM as a method is not yet widely prevalent in fly neuroscience, but recent demonstrations of its potential are likely to increase its use. Future efforts will benefit from the description of the properties of the autofluorescence signal to evaluate how autofluorescence may impact measures of FL of genetically engineered indicators.

Recommendations for the authors

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) Y axes in Figures 1e, 2c, 3b,c are misleading. They must start at 0.

Although we agree that making the Y axes start at 0 is preferable, in our case it makes it difficult to observe the dispersion of the data at the same time (your next suggestion). To make it clearer to the reader that the axes do not start at 0, a broken Y-axis is now displayed in every concerned figure.

(2) These same plots should have individual data points represented, for increased clarity and transparency.

Individual data points were added on all boxplots.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

I am evaluating this paper as a fly neuroscientist with experience in neurophysiology, including calcium imaging. I have little experience with FLIM but anticipate its use growing as more microscopes and killer apps are developed. From this perspective, I value the opportunity to dig into FLIM and try to understand this autofluorescence signal. I think the effort to show each piece of the analysis pipeline is valuable. The figures are quite beautiful and easy to follow. My main suggestion is to consider moving some of the supplemental data to the main figures. eLife allows unlimited figures, moving key pieces of the pipeline to the main figures would make for smoother reading and emphasize the technical care taken in this study.

We thank the reviewer for their feedback. Following their advice we have moved panels from the supplementary figures to the main text (see new Figure 2).

Unfortunately, the scientific questions and biological data do not rise to the typical standard in the field to support the claims in the title, "In vivo autofluorescence lifetime imaging of the Drosophila brain captures metabolic shifts associated with memory formation". The authors also clearly state what the next steps are: "hypothesis-driven approaches that rely on metabolite-specific sensors" (Intro). The advantage of fly neuroscience is the extensive library of genetic reagents that enable perturbations. The key manipulation in this study is the electric shock conditioning paradigm that subtly shifts the distribution of a parameter fit to an exponential decay in the somas of alpha/beta KCs vs others. This feels like an initial finding that deserves follow-up; but is it a large enough result to motivate a future student to pick this project up? The larger effect appears to be the gradients in f_free across KCs overall (Figure 2b). How does this change with conditioning?

We acknowledge that the observed metabolic shift is modest relative to the variability of f_free and agree that additional corroborating experiments would further strengthen this result. Nevertheless, we believe it remains a valid and valuable finding that will be of interest to researchers in the field. The reviewer is right in pointing out that the gradient across KCs is higher in magnitude, however, the fact that this technique can also report experience-dependent changes, in addition to innate heterogeneities across different cell types, is a major incentive for people who could be interested in applying NAD(P)H FLIM in the future. For this reason, we consider it appropriate to retain mention of the memory-induced shift in the title, while making it less assertive and adding a reference to the structural heterogeneities of f_free revealed in the study. We have also rephrased the abstract to adopt a more cautious tone and expanded the discussion to clarify why a low-magnitude shift in f_free can still carry biological significance in this context. Finally, we have added the results of a new set of data involving the knockdown of ALAT in Kenyon cells, to further support the relevance of our observation relative to memory formation, despite its small magnitude. We believe that these elements together form a good basis for future investigations and that the manuscript merits publication in its present form.

Together, I would recommend reshaping the paper as a methods paper that asks the question, what are the spatial properties of NADPH FL across the brain? The importance of this question is clear in the context of other work on energy metabolism in the MBs. 2P FLIM will likely always have to account for autofluorescence, so this will be of interest. The careful technical work that is the strength of the manuscript could be featured, and whether conditioning shifts f_free could be a curio that might entice future work.

By transferring panels of the supplementary figures to the main text (see new Figure 2) as suggested by Reviewer 2, we have reinforced the methodological part of the manuscript. For the reasons explained above, we however still mention the ‘biological’ findings in the title and abstract.

Minor recommendations on science:

Figure 2C. Plotting either individual data points or distributions would be more convincing.

Individual data points were added on all boxplots.

There are a few mentions of glia. What are the authors' expectations for metabolic pathways in glia vs. neurons? Are glia expected to use one more than the other? The work by Rabah suggests it should be different and perhaps complementary to neurons. Can a glial marker be used in addition to KC markers? This seems crucial to being able to distinguish metabolic changes in KC somata from those in glia.

Drosophila cortex glia are thought to play a similar role as astrocytes in vertebrates (see Introduction). In that perspective, we expect cortex glia to display a higher level of glycolysis than neurons. The work by Rabah et al. is coherent with this hypothesis. Reviewer 2 is right in pointing out that using a glial marker would be interesting. However, current technical limitations make such experiments challenging. These limitations are now exposed in the discussion.

The question of whether KC somata positions are stereotyped can probably be answered in other ways as well. For example, the KCs are in the FAFB connectomic data set and the hemibrain. How do the somata positions compare?

The reviewer’s suggestion is indeed interesting. However, the FAFB and hemibrain connectomic datasets are based on only two individual flies, which probably limits their suitability for assessing the stereotypy of KC subtype distributions. In addition, aligning our data with the FAFB dataset would represent substantial additional work.

The free parameter tau_bound is mysterious if it can be influenced by the identity of the protein. Are there candidate NADPH binding partners that have a spatial distribution in confocal images that could explain the difference between somas and calyx?

There are indeed dozens of NADH- or NADPH-binding proteins. For this reason, in all studies implementing exponential fitting of metabolic FLIM data, tau_bound is considered a complex combination of the contributions from many different proteins. In addition, one should keep in mind that the number of cell types contributing to the autofluorescence signal in the mushroom body calyx (Kenyon cells, astrocyte-like and ensheathing glia, APL neurons, olfactory projection neurons, dopamine neurons) is much higher than in the somas (only Kenyon cells and cortex glia). This could also participate in the observed difference. Hence, focusing on intracellular heterogeneities of potential NAD(P)H binding partners seems premature at that stage.

The phrase "noticeable but not statistically significant" is misleading.

We agree with the reviewer and have removed “noticeable but” from the sentence in the new version of the manuscript.

Minor recommendations on presentation:

The Introduction can be streamlined.

We agree that some parts of the Introduction can seem a bit long for experts of a particular field. However, we think that this level of detail makes the article easily accessible for neuroscientists working on Drosophila and other animal models but not necessarily with FLIM, as well as for experts in energy metabolism that may be familiar with FLIM but not with Drosophila neuroscience.

-

-

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This paper applies a computational model to behavior in a probabilistic operant reward learning task (a 3-armed bandit) to uncover differences between individuals with temporomandibular disorder (TMD) compared with healthy controls. Integrating computational principles and models into pain research is an important direction, and the findings here suggest that TMD is associated with subtle changes in how uncertainty is represented over time as individuals learn to make choices that maximize reward. There are a number of strengths, including the comparison of a volatile Kalman filter (vKF) model to some standard base models (Rescorla Wagner with 1 or 2 learning rates) and parameter recovery analyses suggesting that the combination of task and vKF model may be able to capture some properties of learning and decision-making under uncertainty that may be altered in those suffering from chronic pain-related conditions.

I've focused my comments in four areas: (1) Questions about the patient population, (2) Questions about what the findings here mean in terms of underlying cognitive/motivational processes, (3) Questions about the broader implications for understanding individuals with TMD and other chronic pain-related disorders, and (4) Technical questions about the models and results.

(1) Patient population

This is a computational modelling study, so it is light on characterization of the population, but the patient characteristics could matter. The paper suggests they were hospitalized, but this is not a condition that requires hospitalization per se. It would be helpful to connect and compare the patient characteristics with large-scale studies of TMD, such as the OPPERA study led by Maixner, Fillingim, and Slade.

(2) What cognitive/motivational processes are altered in TMD