One online company, Books by the Foot, offers to ‘curate a library that matches both your personality and your space’, promising to provide books ‘based on colour, binding, subject, size, height, and more to create a collection that looks great’.

- Feb 2023

-

aeon.co aeon.co

-

-

Unlike books, tablets do not offer a medium for demonstrating taste and refinement. That is why interior decorators use shelves of books to create an impression of elegance and refinement in the room.

-

If Seneca or Martial were around today, they would probably write sarcastic epigrams about the very public exhibition of reading text messages and in-your-face displays of texting. Digital reading, like the perusing of ancient scrolls, constitutes an important statement about who we are. Like the public readers of Martial’s Rome, the avid readers of text messages and other forms of social media appear to be everywhere. Though in both cases the performers of reading are tirelessly constructing their self-image, the identity they aspire to establish is very different. Young people sitting in a bar checking their phones for texts are not making a statement about their refined literary status. They are signalling that they are connected and – most importantly – that their attention is in constant demand.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Just as with hisinterleaved volumes of Graetz’s Geschichte der Juden,

Tags

Annotators

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Beginner question .t3_112wup1._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } I see that a lot of people have the main categories as natural sciences. Social sciences etcCan I switch it toReligionActivitiesFoodOrganizationMad weird thoughtsCommunication

reply to u/Turbulent-Focus-1389 at https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/112wup1/beginner_question/

I'd recommend you do your best to stay away from rigid category-like classifications and see what develops. For specifics see: https://boffosocko.com/2023/01/19/on-the-interdisciplinarity-of-zettelkasten-card-numbering-topical-headings-and-indices/

If it's easier to conceptualize, think of it all like a map which may have place names, but also has numerical coordinates. Sometimes a specific name like Richard Macksey's house is useful, but other times thinking about a specific coordinate and the general neighborhoods around them will be far more useful in your community development plan. A religion-only neighborhood without religious activities, religious food, religious organization or communication will be a a sad one indeed. If you segregate your communities, they're likely not to be very happy places for co-mingling of ideas and the potential resultant creativity you'll get out of them.

Bob Doto also suggests a similar philosophy in some of his work, particularly with respect to folgezettel: https://writing.bobdoto.computer/zettelkasten/

I'll note that this is an incredibly hard thing to do at the start, but it's one which you may very well wish you had done from the beginning.

-

-

wordcraft-writers-workshop.appspot.com wordcraft-writers-workshop.appspot.com

-

Writers struggled with the fickle nature of the system. They often spent a great deal of time wading through Wordcraft's suggestions before finding anything interesting enough to be useful. Even when writers struck gold, it proved challenging to consistently reproduce the behavior. Not surprisingly, writers who had spent time studying the technical underpinnings of large language models or who had worked with them before were better able to get the tool to do what they wanted.

Because one may need to spend an inordinate amount of time filtering through potentially bad suggestions of artificial intelligence, the time and energy spent keeping a commonplace book or zettelkasten may pay off magnificently in the long run.

-

“...it can be very useful for coming up with ideas out of thin air, essentially. All you need is a little bit of seed text, maybe some notes on a story you've been thinking about or random bits of inspiration and you can hit a button that gives you nearly infinite story ideas.”- Eugenia Triantafyllou

Eugenia Triantafyllou is talking about crutches for creativity and inspiration, but seems to miss the value of collecting interesting tidbits along the road of life that one can use later. Instead, the emphasis here becomes one of relying on an artificial intelligence doing it for you at the "hit of a button". If this is the case, then why not just let the artificial intelligence do all the work for you?

This is the area where the cultural loss of mnemonics used in orality or even the simple commonplace book will make us easier prey for (over-)reliance on technology.

Is serendipity really serendipity if it's programmed for you?

-

-

sciencegarden.net sciencegarden.net

-

Neben den Methoden herkömmlicher Recherche werden daher normalerweise Zettelkästen angelegt, in denen auf Karteikarten notiert ist, was ständig zitiert werden muss. Studenten erproben dies oft zum ersten mal intensiv für ihre Diplomarbeit. Nach Schlagworten und Autoren werden Notizen alphabetisch geordnet und was in den Kasten einsortiert wurde, kann man auch wieder herausholen.

Google translate:

In addition to the methods of conventional research, card boxes are usually created in which index cards are used to record what needs to be constantly quoted. Students often try this out intensively for their diploma thesis for the first time. Notes are sorted alphabetically according to keywords and authors, and what has been sorted into the box can also be taken out again.

An indication from 2001 of the state of the art of zettelkasten written in German. Note that the description is focused more on the index card or slip-based version of a commonplace book sorted alphabetically by keywords and authors primarily for quoting. Most students trying the method for the first time are those working on graduate level theses.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Categories mean determination of internal structure less flexibility, especially “in the long run“ of knowledgemanagement and storage

The fact that Luhmann changed the structure of his zettelkasten with respect to the longer history of note taking and note accumulation allowed him several useful affordances.

In older commonplacing and slip box methods, one would often store their notes by topic category or perhaps by project. This mean that after collection one had to do additional work of laying them out into some sort of outline to create arguments and then write them out for publication. This also meant that one was faced with the problem of multiple storage or copying out notes multiple times to file under various different subject headings.

Luhmann overcame both of these problems by eliminating categories and placing ideas closest to their most relevant neighbor and numbering them in a branching fashion. Doing this front loads some of the thinking and outlining work which would often be done later, though it's likely easier to do when one has the fullest context of a note after they've made it when it is still freshest in their mind. It also means that each note is linked to at least one other note in the system. This helps notes from being lost and allows a simpler indexing structure whereby one only needs to use a few index entries to get close to the neighborhood of an idea as most other related ideas are likely to be nearby within a handful or more of index cards.

Going from index to branches on the tree is relatively easy and also serves the function of reminding one of interesting prior reading and ideas as one either searches for specific notes or searches for placing future notes.

When it comes to ultimately producing papers, one's notes already have a pre-arranged sort of outline which can then be more easily copied over for publication, though one can certainly still use other cross-links and further rearranging if one wishes.

Older methods focused on broad accretion of materials into subject ordered piles while Luhmann's practice not only aggregated them, but slowly and assuredly grew them into more orderly trains of thought as he collected.

Link to: The description in Technik des wissenschaftlichen Arbeitens (section 1.2 Die Kartei) at https://hypothes.is/a/-qiwyiNbEe2yPmPOIojH1g which heavily highlights all the downsides, though it doesn't frame them that way.

-

-

www.edwinwenink.xyz www.edwinwenink.xyzAbout1

-

This weblog is a mnemonic device.

Blogs as digital commonplace books

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.goodreads.com www.goodreads.com

-

For newer non-surveillance capitalist alternatives to Goodreads:

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

rd.jae.su rd.jae.su

-

Also, what’s a good book to start with if I want to read more James Tate? Thank you for your music and its endless place in my life. 21 u/dcberman David Berman Jul 15 '19 Thank you. With Tate just go get "Selected Poems". It changed my thinking as sure as the Butthole Surfers did* I recomend reading the last three chapters of Otto Rank's Art and Artist, especially "the artist's fight with art".

-

My only question: What is one book or record that has moved you emotionally in the past year? PS: I read somewhere you weren't much of a movie guy. I'm not either. But, I recommend watching Paris, Texas starring Harry Dean Stanton (if you haven't seen it already). It reminded me of you and your writing. Cheers. 15 u/dcberman David Berman Jul 15 '19 Diary of a Man in Despair by Friedrich Reck-Malleczewin. A for me, heretofore unseen view of Germany in the thirties and forties by a bavarian "landed aristocrat" choking down extravagant contempt while he watches it all go to hell.

-

Also, do you have any book recommendations for someone about to start college? 72 u/dcberman David Berman Jul 15 '19 edited Jul 15 '19 I'm with-holding. Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton Complete Emily Dickinson

-

What is your favorite book/novel? Do you have any recommendations for us? 26 u/dcberman David Berman Jul 15 '19 Ill recommend a Robert Stone short story i go back to re-read every year at least once. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1987/06/08/helping-2

David Berman on a fave book.

-

-

biblioklept.org biblioklept.org

-

Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton Complete Emily Dickinson

Some of David Berman's book tips.

-

-

www.nashvillescene.com www.nashvillescene.com

-

He told me his favorite novel was Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

With a category you can just bypass idea-connection and jump right to storage.

Categorizing ideas (and or indexing them for search) can be useful for quick bulk storage, but the additional work of linking ideas to each other with in a Luhmann-esque zettelkasten can be more useful in the long term in developing ideas.

Storage by category means that ideas aren't immediately developed explicitly, but it means that that work is pushed until some later time at which the connections must be made to turn them into longer works (articles, papers, essays, books, etc.)

-

- Jan 2023

-

Local file Local file

-

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Maxims and Reflections. Penguin Classics. Penguin Books, 1998.

urn:x-pdf:577d8c2ae537c748bc9ae3d1e12ecb38

-

Goethe's Maxims and Reflections represents a commonplace book of sorts.

Who numbered the maxims though? Was it Goethe or someone after him?

(stray note on a slip of paper dated 2022-10-27)

-

-

bactra.org bactra.org

-

An interesting raw html-based website that also serves the functions of notebook and to some extent a digital commonplace.

Cosma Shalizi is a professor in the statistics department at CMU.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPqjgN-pNDw

When did the switch in commonplace book framing did the idea of "second brain" hit? (This may be the first time I've seen it personally. Does it appear in other places?) Sift through r/commonplace books to see if there are mentions there.

By keeping one's commonplace in an analog form, it forces a greater level of intentionality because it's harder to excerpt material by hand. Doing this requires greater work than arbitrarily excerpting almost everything digitally. Manual provides a higher bar of value and edits out the lower value material.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

In the end I decided: everyone hates a long essay; everyoneloves a short book. Why not turn the essay into a freestanding workand let it stand on its own merits?And that is what I have done.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifDi2SsQjQM

Comparing the various e-note/e-reader devices, Kit Betts-Masters ranks them overall as follows: - Boox Note Air 2 - Supernote A5X - Remarkable 2 - Bigme Inknote - Kobo Elipsa - Boyue P10

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.connectedtext.com www.connectedtext.com

-

I accumulated altogether between 5.000 and 6.000 note cards from 1974 to 1985, most of which I still keep for sentimental reasons and sometimes actually still consult.

Manfred Kuehn's index card commonplace from 1974 - 1985

At 5 - 6,000 cards in 11 years from 1974 to 1985, Kuehn would have made somewhere in the neighborhood of 1.25 - 1.49 note per day.

-

-

-

I've decided I don't care (too much) where new notes go .t3_10mjwq9._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/jackbaty at https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/10mjwq9/ive_decided_i_dont_care_too_much_where_new_notes/

u/jackbaty, If it doesn't make sense for you (yet, or for your specific needs), you can always follow in the footsteps of the hundreds of thousands who used a topical subject heading method of the commonplace book before Luhmann's example shifted the space over the last decade. If it worked for Francis Bacon, you'll probably be alright too... (See: https://boffosocko.com/2022/06/10/reframing-and-simplifying-the-idea-of-how-to-keep-a-zettelkasten/)

I find that sometimes, it is useful to bank up a few dozen cards before filing/linking them together. Other times I'll file them by category in a commonplace book like system to ruminate a bit only later to move them to a separate Luhmann-esque zettelkasten area where they're more tightly linked with the ideas around them. After you've been doing it a while, it will be easier to more tightly integrate the three-way conversation or argument you're having between yourself, your card index, and the sources you're thinking about (or reading, watching, listening to). You mention that "my brain needs at least some level of structure", and I totally get it, as most of us (myself included) are programmed to work that way. I've written some thoughts on this recently which may help provide some motivation to get you around it: https://boffosocko.com/2023/01/19/on-the-interdisciplinarity-of-zettelkasten-card-numbering-topical-headings-and-indices/

It helps to have a pointed reason for why you're doing all this in the first place and that reason will dramatically help to shape your practice and its ultimate structure.

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

Mark Bernstein suggested this with respect to note taking and commonplace book traditions in a Tools For Thought Rocks talk: https://lu.ma/2u5f7ky0

Mallon, Thomas. A Book of One’s Own: People and Their Diaries. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1984.

-

-

-

Browsing through Walten’s notes also helped Jagersma to get to know the pamphleteer better, even though he is been dead for three hundred years. “The Memoriaelen say a lot about him. I could read how Walten did his research, follow his fascinations, and see the ideas for pieces he was not able to work out anymore. In a way, these two notebooks are a kind of self-portrait.”

-

And the third category is for things that inspire me but that I don’t yet know exactly how to use. This category is actually the most interesting.”

Many people collect notes that they're not sure what to do with or even where to put them. Neuroscience student and researcher Charlotte Fraza keeps her version of these notes in a category of "things that inspire me, but I don't yet know exactly how to use. She feels that compared to the other categories of actionable specific use and sources, this inspiration category is the most interesting to her.

-

He also collected facts about all kinds of people, including his enemies. For example, he took note of any gossip about conservative ministers who disagreed with him. He recorded their visits to prostitutes in his Memoriaelen.

-

In Walten’s two notebooks, referred to as Memoriaelen, Jagersma discovered a lot of details about the pamphleteer’s life. “These notebooks look a bit like the Moleskine notebooks that we know today,” says Jagersma, “but thicker, and bound in parchment.” In the more than five hundred pages, Walten collected all kinds of information. Jagersma lists the categories: “Personal anecdotes, philosophical and theological reflections, ideas, incursions, medical recipes, accounts of alchemical experiments, but also departure and arrival dates of the trekschuit (sail- or horse-drawn boat). The notebooks also contain lists of books he still wanted to read.”

-

Delicate and precise, neatly arranged in alphabetical lemmas. I stumbled across the manuscripts in the Special Collections of the Leiden University Library, where they were listed in the inventory as ‘Adversaria of mixed content’. Without further explanation, except that their author was Jan Wagenaar. This eighteenth-century author was a household name in his time, writing about history, theology, and politics. Now here I was, looking at the notes he had used to write all those books, sermons, and pamphlets.The four leather-bound volumes contained pages and pages of lemmas on a variety of topics, from ‘concubines’ to ‘thatched roofs in the cities of Holland’. The lemmas included excerpts from a variety of texts, including snippets in French, English and Hebrew. This was how Wagenaar tried to organise his information flows, subsequently using this information to produce new texts.

Jan Wagenaar's four leather-bound commonplace books are housed in the Special Collections of the Leiden University Library inventoried as "Adversaria of mixed content."

They contain excerpts in French, English, and Hebrew and are arranged by topical heading.

-

-

forums.zotero.org forums.zotero.org

-

Cite these as Book/Book Section as appropriate. If you need to specify that it is an ebook (most citation styles don’t require this—there isn’t a real difference from a physical book), specify that in Extra like this:Medium: Kindle ebook

https://forums.zotero.org/discussion/77941/the-best-way-to-cite-ebooks-currently

To sub-specify an ebook as opposed to a physical book in Zotero, in the Extra section, add a note like

Medium: Kindle .mobi.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

press.princeton.edu press.princeton.edu

-

https://press.princeton.edu/series/ancient-wisdom-for-modern-readers

This appears like Princeton University Press is publishing sections of someone's commonplace books as stand alone issues per heading where each chapter has a one or more selections (in the original language with new translations).

This almost feels like a version of The Great Books of the Western World watered down for a modern audience?

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

How do you maintain the interdisciplinarity of your zettlekasten? .t3_10f9tnk._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

As humans we're good at separating things based on categories. The Dewey Decimal System systematically separates mathematics and history into disparate locations, but your zettelkasten shouldn't force this by overthinking categories. Perhaps the overlap of math and history is exactly the interdisciplinary topic you're working toward? If this is the case, just put cards into the slip box closest to their nearest related intellectual neighbor—and by this I mean nearest related to you, not to Melvil Dewey or anyone else. Over time, through growth and branching, ideas will fill in the interstitial spaces and neighboring ideas will slowly percolate and intermix. Your interests will slowly emerge into various bunches of cards in your box. Things you may have thought were important can separate away and end up on sparse branches while other areas flourish.

If you make the (false) choice to separate math and history into different "sections" it will be much harder for them to grow and intertwine in an organic and truly disciplinary way. Universities have done this sort of separation for hundreds of years and as a result, their engineering faculty can be buildings or even entire campuses away from their medical faculty who now want to work together in new interdisciplinary ways. This creates a physical barrier to more efficient and productive innovation and creativity. It's your zettelkasten, so put those ideas right next to each other from the start so they can do the work of serendipity and surprise for you. Do not artificially separate your favorite ideas. Let them mix and mingle and see what comes out of them.

If you feel the need to categorize and separate them in such a surgical fashion, then let your index be the place where this happens. This is what indices are for! Put the locations into the index to create the semantic separation. Math related material gets indexed under "M" and history under "H". Now those ideas can be mixed up in your box, but they're still findable. DO NOT USE OR CONSIDER YOUR NUMBERS AS TOPICAL HEADINGS!!! Don't make the fatal mistake of thinking this. The numbers are just that, numbers. They are there solely for you to be able to easily find the geographic location of individual cards quickly or perhaps recreate an order if you remove and mix a bunch for fun or (heaven forfend) accidentally tip your box out onto the floor. Each part has of the system has its job: the numbers allow you to find things where you expect them to be and the index does the work of tracking and separating topics if you need that.

The broader zettelkasten, tools for thought, and creativity community does a terrible job of explaining the "why" portion of what is going on here with respect to Luhmann's set up. Your zettelkasten is a crucible of ideas placed in juxtaposition with each other. Traversing through them and allowing them to collide in interesting and random ways is part of what will create a pre-programmed serendipity, surprise, and combinatorial creativity for your ideas. They help you to become more fruitful, inventive, and creative.

Broadly the same thing is happening with respect to the structure of commonplace books. There one needs to do more work of randomly reading through and revisiting portions to cause the work or serendipity and admixture, but the end results are roughly the same. With the zettelkasten, it's a bit easier for your favorite ideas to accumulate into one place (or neighborhood) for easier growth because you can move them around and juxtapose them as you add them rather than traversing from page 57 in one notebook to page 532 in another.

If you use your numbers as topical or category headings you'll artificially create dreadful neighborhoods for your ideas to live in. You want a diversity of ideas mixing together to create new ideas. To get a sense of this visually, play the game Parable of the Polygons in which one categorizes and separates (or doesn't) triangles and squares. The game created by Vi Hart and Nicky Case based on the research of Thomas Schelling provides a solid example of the sort of statistical mechanics going on with ideas in your zettelkasten when they're categorized rigidly. If you rigidly categorize ideas and separate them, you'll drastically minimize the chance of creating the sort of useful serendipity of intermixed and innovative ideas.

It's much harder to know what happens when you mix anthropology with complexity theory if they're in separate parts of your mental library, but if those are the things that get you going, then definitely put them right next to each other in your slip box. See what happens. If they're interesting and useful, they've got explicit numerical locators and are cross referenced in your index, so they're unlikely to get lost. Be experimental occasionally. Don't put that card on Henry David Thoreau in the section on writers, nature, or Concord, Massachusetts if those aren't interesting to you. Besides everyone has already done that. Instead put him next to your work on innovation and pencils because it's much easier to become a writer, philosopher, and intellectual when your family's successful pencil manufacturing business can pay for you to attend Harvard and your house is always full of writing instruments from a young age. Now you've got something interesting and creative. (And if you must, you can always link the card numerically to the other transcendentalists across the way.)

In case they didn't hear it in the back, I'll shout it again: ACTIVELY WORK AGAINST YOUR NATURAL URGE TO USE YOUR ZETTELKASTEN NUMBERS AS TOPICAL HEADINGS!!!

-

-

Local file Local file

-

it maybe well to take the notes directly in the text book, either on the margins,between the leaves, or on insert-leaves which book-shops sell for that pu

"insert-eaves" !!

I've heard of interleaved books, but was unaware of the practice of book shops selling "insert-leaves" being specifically sold for the purpose of inserting notes into books.

-

-

petersmith.org petersmith.org

-

PeterSmith.Org is my commonplace book, covering teaching, research, technology, and whatever else takes my fancy. This site is in a constant state of development and 'becoming'.

Peter Smith calls his website his commonplace book.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

to heaven. I see that if my facts were sufficiently vital and significant,—perhaps transmuted more into the substance of the human mind,—Ishould need but one book of poetry to contain them all.

I have a commonplace-book for facts and another for poetry, but I find it difficult always to preserve the vague distinction which I had in my mind, for the most interesting and beautiful facts are so much the more poetry and that is their success. They are translated from earth

—Henry David Thoreau February 18, 1852

Rather than have two commonplaces, one for facts and one for poetry, if one can more carefully and successfully translate one's words and thoughts, they they might all be kept in the commonplace book of poetry.

-

Finally, I should say that this abridgment does not claim to beobjective. I chose passages for inclusion not necessarily because oftheir importance to Thoreau’s biography, or to cultural or naturalhistory, but because I liked them: the book is shaped by my personalproclivities as much as by anything else—a preference for berryingover fishing, owls over muskrats, ice over sunsets, to name a few atrandom.

Fascinating to think that Damion Searls edited this edition of Thoreau's journals almost as if they were his (Searls') own commonplace book of Thoreau's journals themselves.

Very meta!

-

Like any journal, Thoreau’s is repetitive, which suggests naturalplaces to shorten the text but these are precisely what need to be keptin order to preserve the feel of a journal, Thoreau’s in particular. Itrimmed many of Thoreau’s repetitions but kept them wheneverpossible, because they are important to Thoreau and because theyare beautiful. Sometimes he repeats himself because he is drafting,revising, constructing sentences solid enough to outlast the centuries.

Henry David Thoreau repeated himself frequently in his journals. Damion Searls who edited an edition of his journals suggested that some of this repetition was for the beauty and pleasure of the act, but that in many examples his repetition was an act of drafting, revising, and constructing.

Scott Scheper has recommended finding the place in one's zettelkasten where one wants to install a card before writing it out. I believe (check this) that he does this in part to prevent one from repeating themselves, but one could use the opportunity and the new context that brings them to an idea again to rewrite or rework and expand on their ideas while they're so inspired.

Thoreau's repetition may have also served the idea of spaced repetition: reminding him of his thoughts as he also revised them. We'll need examples of this through his writing to support such a claim. As the editor of this volume indicates that he removed some of the repetition, it may be better to go back to original sources than to look for these examples here.

(This last paragraph on repetition was inspired by attempting to type a tag for repetition and seeing "spaced repetition" pop up. This is an example in my own writing practice where the serendipity of a previously tagged word auto-populating/auto-completing in my interface helps to trigger new thoughts and ideas from a combinatorial creativity perspective.)

-

Sometimes, Isuspect, he copied his own words because he liked to copy: no one’scommonplace books could run to a million words—those are just theones that survive, in addition to a two-million-word Journal, andenormous quantities of other writing—without a sheer love of sittingwith pen in hand, a printed book and a blank page both open before

him.

-

Jan. 22. To set down such choice experiences that my own writingsmay inspire me and at last I may make wholes of parts. Certainly it isa distinct profession to rescue from oblivion and to fix the sentimentsand thoughts which visit all men more or less generally, that thecontemplation of the unfinished picture may suggest its harmoniouscompletion. Associate reverently and as much as you can with yourloftiest thoughts. Each thought that is welcomed and recorded is anest egg, by the side of which more will be laid. Thoughts accidentallythrown together become a frame in which more may be developedand exhibited. Perhaps this is the main value of a habit of writing, ofkeeping a journal,—that so we remember our best hours and stimulateourselves. My thoughts are my company. They have a certainindividuality and separate existence, aye, personality. Having bychance recorded a few disconnected thoughts and then brought theminto juxtaposition, they suggest a whole new field in which it waspossible to labor and to think. Thought begat thought.

!!!!

Henry David Thoreau from 1852

Tags

- commonplace books

- translations

- juxtaposition

- rhetoric

- inspiration

- writing advice

- editing

- Henry David Thoreau

- poetry

- spaced repetition

- repetition in writing

- love of writing

- associative thinking

- Damion Searls

- revision

- facts

- lost in translation

- associative trails

- idea links

- quotes

- 1852

- creativity

- idea crystallization

- note taking affordances

- note taking

- combinatorial creativity

- note taking as aide-mémoire

- writing for understanding

- journaling

- writing process

- only one commonplace

Annotators

-

-

forum.gettingthingsdone.com forum.gettingthingsdone.com

-

May 19, 2004 #1 Hello everyone here at the forum. I want to thank everyone here for all of the helpful and informative advice on GTD. I am a beginner in the field of GTD and wish to give back some of what I have received. What is posted below is not much of tips-and-tricks I found it very helpful in understanding GTD. The paragraphs posted below are from the book Lila, by Robert Pirsig. Some of you may have read the book and some may have not. It’s an outstanding read on philosophy. Robert Pirsig wrote his philosophy using what David Allen does, basically getting everything out of his head. I found Robert Pirsigs writing on it fascinating and it gave me a wider perspective in using GTD. I hope you all enjoy it, and by all means check out the book, Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals. Thanks everyone. arthur

Arthur introduces the topic of Robert Pirsig and slips into the GTD conversation on 2004-05-19.

Was this a precursor link to the Pile of Index Cards in 2006?

Note that there doesn't seem to be any discussion of any of the methods with respect to direct knowledge management until the very end in which arthur returns almost four months later to describe a 4 x 6" card index with various topics he's using for filing away his knowledge on cards. He's essentially recreated the index card based commonplace book suggested by Robert Pirsig in Lila.

-

-

hcommons.social hcommons.social

-

Ryan Randall @ryanrandall@hcommons.socialEarnest but still solidifying #pkm take:The ever-rising popularity of personal knowledge management tools indexes the need for liberal arts approaches. Particularly, but not exclusively, in STEM education.When people widely reinvent the concept/practice of commonplace books without building on centuries of prior knowledge (currently institutionalized in fields like library & information studies, English, rhetoric & composition, or media & communication studies), that's not "innovation."Instead, we're seeing some unfortunate combination of lost knowledge, missed opportunities, and capitalism selectively forgetting in order to manufacture a market.

https://hcommons.social/@ryanrandall/109677171177320098

-

-

app.thebrain.com app.thebrain.comTheBrain1

-

genizaprojects.princeton.edu genizaprojects.princeton.edu

-

https://genizaprojects.princeton.edu/indexcards/index.php?a=themes

A digitized web-based version of S.D. Goitein's commonplace book using index cards.

Wowzers!

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Many of the topic cards served as the skeleton for Mediterranean Society and can be usedto study how Goitein constructed his magnum opus. To give just one example, in roll 26 wehave the index cards for Mediterranean Society, chap. 3, B, 1, “Friendship” and “InformalCooperation” (slides 375–99, drawer 24 [7D], 431–51), B, 2, “Partnership and Commenda”(slides 400–451, cards 452–83), and so forth.

Cards from the topically arranged index cards in Goitein's sub-collection of 20,000 served as the skeleton of his magnum opus Mediterranean Society.

-

Goitein’s index cards can be divided into two general types: those thatfocus on a specific topic (children, clothing, family, food, weather, etc.) andthose that serve as research tools for the study of the Geniza. 48

-

It is, however, important to keep in mind that, reflecting the trajectory ofGoitein’s study of the Geniza, there are often two sets of cards for a givensubject, one general and one related to the India Book.44

Goitein, “Involvement in Geniza Research,” 144.

Goitein's cards are segmented into two sets: one for subjects and one related to the India Book.

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08BZWJDHN/

Example of a modern day waste book for keeping track of one's accounting.

dimensions 3.5 x 5"

-

-

docs.joinbookwyrm.com docs.joinbookwyrm.com

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

bookwyrm.social bookwyrm.socialBookWyrm1

-

-

wiki.rel8.dev wiki.rel8.dev

-

Books and Presentations Are Playlists, so let's create a NeoBook this way.

https://wiki.rel8.dev/co-write_a_neobook

A playlist of related index cards from a Luhmann-esque zettelkasten could be considered a playlist that comprises an article or a longer work like a book.

Just as one can create a list of all the paths through a Choose Your Own Adventure book, one could do something similar with linked notes. Ward Cunningham has done something similar to this programmatically with the idea of a Markov monkey.

-

-

-

https://onyxboox.com/boox_nova3

@adamprocter @chrisaldrich i really like my boox nova3 color – it’s ✌️ just ✌️ a color-paper android device with a custom integrated launcher/ereader software but it can have f-droid or play store sideloaded on to it. i mostly use it with koreader+wallabag but there surely is an RSS or NNW client that works decently on it in B/W mode via rrix Jan 03, 2023, 12:47 https://notes.whatthefuck.computer/objects/0f1ffdd4-4e27-4962-ae53-0c039494bef9

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

slate.com slate.com

-

Andrew Blum, author of The Weather Machine: A Journey Inside the Forecast

-

-

tedgioia.substack.com tedgioia.substack.com

-

creative fields like music and writing live and die based on creativity, not financial statements and branding deals.

-

“I don’t think books are overpriced.”

-

- Dec 2022

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

I’m a screenwriter. One of the reasons I use Obsidian is the ability to hashtag. It sounds so simple, but being able to tag notes with #theme or #sceneideas helps create linkages between notes that would not otherwise be linked. My ZK literally tells me what the movie is really about.

via u/The_Bee_Sneeze

Example of someone using Obsidian with a zettelkasten focus to write screenplays.

Thought the example appears in r/Zettelkasten, one must wonder at how Luhmann-esque such a practice really appears?

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

I'm a multi-media artist, so I have many ideas about fashion pieces, artworks, music, etc. that i'd want to make. Would I plug in these ideas as 'fleeting notes' until they're more cemented? would you recommend I keep separate my 'original' ideas and the ZK note-taking system?

I gave some examples of uses in arts/media a while back that you might find interesting for your use case: https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/xdrb0k/comment/iofo5vv/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

In particular, a more commonplace book approach or something along the lines of Chapter 6 of Twyla Tharpe's book may be more useful or productive for your use case.

-

-

johnmount.github.io johnmount.github.io

-

My day to day notebook is a soft 5 inch by 3.5 inch pocket notebook as shown below. I use a mechanical pencil when out and about (no breakage or sharpening) and take a small eraser (in this case an eraser shaped like Lego). This book is good for notes and ideas. Notice I cross them out when I have acted on them in some way (done the work, or given up on the idea). The goal of the daily notebook is to eventually throw it away (not save it). So all work needs to move out and I need to be able to know it has been moved.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

“The florilegium was a type of ‘double memory’ towhich scholars could resort anytime their personal memory failed, the filingcabinet behaves as a true communication partner with its own idiosyncrasiesand its own opinions.”31

I'll have to look into this argument as it feels dramatically false to me.

The only way I can see this is if one only uses their commonplace for excerpts and no other notes, a pattern which may have been the case for some, but certainly not all.

-

Yet, there are shortcomings of commonplace books. They embody that of a“subsidiary memory,” whereas the Antinet is more than this. The Antinet isa second mind, an equal.

Why though? The slight difference in form doesn't account for any differences claimed here.

-

The limitations of commonplacebooks centers around the following: they only enable short-term knowledgedevelopment. They do not cater to allowing thoughts to evolve over time,infinitely. They do not allow for the infinite internal branching and expansionof ideas.

sigh

This is untrue in practice. They can evolve, they just do so in different ways. Prior to Luhmann's example, they have done so for centuries.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Although some of them took a lot of time to create (I literally wrote whole book summaries for a while), their value was negligible in hindsight.

What was the purpose of these summaries? Were they of areas which weren't readily apparent in hindsight? Often most people's long summaries are really just encapsulalizations of what is apparent from the book jacket. Why bother with this? If they're just summaries of the obvious, then they're usually useless for review specifically because they're obvious. This is must make-work.

You want to pull out the specific hard-core insights that weren't obvious to you from the jump.

Most self-help books can be motivating while reading them and the motivation can be helpful, but generally they will only contain one or two useful ideas

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Presumed to have been written in the fifth century Stobaeus compiled an extensive two volume manuscript commonly known as The Anthologies of excerpts containing 1,430 poetry and prose quotations of works of which only 315 are still extant in the 21st century.[10]

footnote: Moller, Violet (2019). The Map of Knowledge (1st ed.). Doubleday. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-385-54176-3.

I wrote this snippet yesterday.

-

-

genizalab.princeton.edu genizalab.princeton.edu

-

Goitein accumulated more than 27,000 index cards in his research work over the span of 35 years. (Approximately 2.1 cards per day.)

His collection can broadly be broken up into two broad categories: 1. Approximately 20,000 cards are notes covering individual topics generally making of the form of a commonplace book using index cards rather than books or notebooks. 2. Over 7,000 cards which contain descriptions of a single fragment from the Cairo Geniza.

A large number of cards in the commonplace book section were used in the production of his magnum opus, a six volume series about aspects of Jewish life in the Middle Ages, which were published as A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza (1967–1993).

-

-

Local file Local file

-

important works like Galen’s On Demonstration, Theophrastus’ OnMines and Aristarchus’ treatise on heliocentric theory (which mighthave changed the course of astronomy dramatically if it hadsurvived) all slipped through the cracks of time.

-

In the latefifth century, a man called Stobaeus compiled a huge anthology of1,430 poetry and prose quotations. Just 315 of them are from worksthat still exist—the rest are lost.

-

Moller, Violet. The Map of Knowledge: A Thousand-Year History of How Classical Ideas Were Lost and Found. 1st ed. New York: Doubleday, 2019. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/546484/the-map-of-knowledge-by-violet-moller/.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Three editions were published by Conrad Gessner (Zurich, 1543; Basle, 1549; Zurich; 1559),

Konrad Gessner published three editions of Stobaeus' Anthology (Zurich, 1543; Basel, 1549; and Zurich, 1559).

He would thus have had this as an example of a compilation of excerpts at his disposal and as an example for his own excerpting work.

-

-

jasontucker.blog jasontucker.blog

-

On my own website(s) I'm looking to write more content and share more of my experiences. I'm at a time in my life that documenting what is going on so I can recall things easier would be helpful, a place to publicly share my notes in hopes that it will help someone else.

Hints of personal website as commonplace book.

-

-

standardebooks.org standardebooks.org

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>awarm.space</span> in Making a modern ebook with Standard Ebooks (<time class='dt-published'>08/02/2021 12:08:19</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

claremontreviewofbooks.com claremontreviewofbooks.com

-

(Microcosm: The Quantum Revolution in Economics and Technology, 1989)

-

(Wealth and Poverty, 1981)

-

(Sexual Suicide, 1973; Men and Marriage, 1986)

-

What Tech Calls Thinking (2020)

What Tech Calls Thinking: An Inquiry Into the Intellectual Bedrock of Silicon Valley by Adrian Daub

-

AI Superpowers (2018)

-

Autonomous Revolution (2020)

The Autonomous Revolution: Reclaiming the Future We’ve Sold to Machines by William Davidow

-

Revolt of the Public (2014)

The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority by Martin Gurri

-

Technocracy in America (2017)

Technocracy in America: Rise of the Info-State by Parag Khanna

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.modernlibrary.com www.modernlibrary.com

-

https://www.modernlibrary.com/top-100/100-best-nonfiction/

What a solid looking list of non-fiction books.

-

-

math.stackexchange.com math.stackexchange.com

-

My freely downloadable Beginning Mathematical Logic is a Study Guide, suggesting introductory readings beginning at sub-Masters level. Take a look at the main introductory suggestions on First-Order Logic, Computability, Set Theory as useful preparation. Tackling mid-level books will help develop your appreciation of mathematical approaches to logic.

This is a reference to a great book "Beginning Mathematical Logic: A Study Guide [18 Feb 2022]" by Peter Smith on "Teach Yourself Logic A Study Guide (and other Book Notes)". The document itself is called "LogicStudyGuide.pdf".

It focuses on mathematical logic and can be a gateway into understanding Gödel's incompleteness theorems.

I found this some time ago when looking for a way to grasp the difference between first-order and second-order logics. I recall enjoying his style of writing and his commentary on the books he refers to. Both recollections still remain true after rereading some of it.

It both serves as an intro to and recommended reading list for the following: - classical logics - first- & second-order - modal logics - model theory<br /> - non-classical logics - intuitionistic - relevant - free - plural - arithmetic, computability, and incompleteness - set theory (naïve and less naïve) - proof theory - algebras for logic - Boolean - Heyting/pseudo-Boolean - higher-order logics - type theory - homotopy type theory

-

- Nov 2022

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

Surrender, his entrancing new memoir.

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

I believe Victor Margolin when he says that he developed his own system. That's what I did in the years before people started widely discussing personal knowledge systems online. Nobody taught me how to do it when I was in college. @chrisaldrich repeatedly tries to connect everyone's knowledge practices to an ongoing tradition that stretches back to commonplace books, but he overstates it. There is such a thing as independent development of a personal knowledge system. I know it because I've lived it. It's not so difficult that it requires extraordinary genius.

Reply to Andy https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/comment/16865#Comment_16865

Andy, I'll take you at your word. You're right that none of it requires extraordinary genius--though many who seem to exhibit extraordinary genius do have variations of these practices in their lives, and the largest proportion of them either read about them or were explicitly taught them.

With these patterns and practices being so deeply rooted in our educational systems for so long (not to mention the heavy influences of our orality and evolved thinking apparatus even prior to literacy), it's a bit difficult for many to truly guarantee that they've done these things independently without heavy cultural and societal influence. As a result, it's not a far stretch for people to evolve their own practices to what works for them and then think that they've invented something new. The common person may not be aware of the old ideas of scala naturae or scholasticism, but they certainly feel them in their daily lives. Commonplacing is not much different.

By analogy, Elon Musk might say he created the Tesla, but it's a far bigger stretch for him to say that he invented a new means of transportation, or a car, or the wheel when we know he's swimming in a culture rife with these items. Humans are historically far better at imitation than innovation. If people truly independently developed systems like these so many times, then in the evolutionary record of these practices we should expect to see more diversity than we do in practice. We might expect to see more innovation than just the plain vanilla adjacent possible. Given Margolin's age, time period, educational background, and areas of expertise, there is statistically very little chance that he hadn't seen or talked about versions of this practice with several dozens of his peers through his lifetime after which he took that tacit knowledge and created his own explicit version which worked for him.

Historian Keith Thomas talks about some of these traditions which he absorbed himself without having read some of the common advice (see London Review of Books https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v32/n11/keith-thomas/diary). He also indicates that he slowly evolved to some of the often advised practices like writing only on one side of a slip, though, like many, he completely omits to state the reason why this is good advice. We can all ignore these rich histories, but we'll probably do so at our own peril and at the expense of wasting some of our time to re-evolve the benefits.

Why are so many here (and in other fora on these topics) showing up regularly to read and talk about their experiences? They're trying to glean some wisdom from the crowds of experimenters to make improvements. In addition to the slow wait for realtime results, I've "cheated" a lot and looked at a much richer historical record of wins and losses to gain more context of our shared intellectual history. I'm reminded of one of Goethe's aphorisms from Maxims and Reflections "Inexperienced people raise questions which were answered by the wise thousands of years ago."

-

-

forum.nim-lang.org forum.nim-lang.org

-

Nim in Action book

todo: procure this

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

data.inventaire.io data.inventaire.io

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

-

-

www.ft.com www.ft.com

-

The Age of Extremes, Eric Hobsbawm

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.netview1

-

We find favorwith Mortimer J. Adler’s stance, from 1940,that “marking up a book is not an act ofmutilation but of love.”18

also:

Full ownership of a book only comes when you have made it a part of yourself, and the best way to make yourself a part of it—which comes to the same thing—is by writing in it. —Adler, Mortimer J., and Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book. Revised and Updated edition. 1940. Reprint, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972.

They also suggest that due to the relative low cost of books, it's easier to justify writing in them, though they carve out an exception for the barbarism of scribbling in library books.

-

-

www.iamabook.online www.iamabook.online

-

https://www.iamabook.online/

-

-

analogoffice.net analogoffice.net

-

https://analogoffice.net/2022/10/28/a-life-in.html

@Guy Reminds me instantaneously of this collection of farm themed pocket notebooks which inspired Field Notes: https://fieldnotesbrand.com/from-seed 📓

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ueMHkGljK0

Robert Greene's method goes back to junior high school when he was practicing something similar. He doesn't say he invented it, and it may be likely that teachers modeled some of the system for him. He revised the system over time to make it work for himself.

- [x] Revisit this for some pull quotes and fine details of his method. (Done on 2022-11-08)

-

Robert Greene: (pruriently) "You want to see my index cards?"<br /> Brian Rose: (curiously) Yeah. Can we?? ... This is epic! timestamp

-

-

www.obsidianroundup.org www.obsidianroundup.org

-

Inevitably, I read and highlight more articles than I have time to fully process in Obsidian. There are currently 483 files in the Readwise/Articles folder and 527 files marked as needing to be processed. I have, depending on how you count, between 3 and 5 jobs right now. I am not going to neatly format all of those files. I am going to focus on the important ones, when I have time.

I suspect that this example of Eleanor Konik's is incredibly common among note takers. They may have vast repositories of collected material which they can reference or use, but typically don't.

In digital contexts it's probably much more common that one will have a larger commonplace book-style collection of notes (either in folders or with tags), and a smaller subsection of more highly processed notes (a la Luhmann's practice perhaps) which are more tightly worked and interlinked.

To a great extent this mirrors much of my own practice as well.

-

-

delong.typepad.com delong.typepad.com

-

. Full ownership of a bookonly comes when you have made it a part of yourself, and thebest way to make yourself a part of it-which comes to thesame thing-is by writing in it.

-

To use a good book as a sedative is conspicuous waste.

-

-

www.fastcompany.com www.fastcompany.com

-

library.harvard.edu library.harvard.edu

-

https://library.harvard.edu/collections/reading-harvard-views-readers-readership-and-reading-history

Reading: Harvard Views of Readers, Readership, and Reading History<br /> Exploring the intellectual, cultural, and political history of reading as reflected in the historical holdings of the Harvard's libraries.

-

-

notebookofghosts.com notebookofghosts.com

-

https://notebookofghosts.com/2018/02/25/a-brief-guide-to-keeping-a-commonplace-book/

very loose and hands-off on dictating others' practices

nothing new to me really...

-

This is one compiler’s approach to keeping a commonplace book.

Commonplacing is a personal practice.

-

-

en.wikisource.org en.wikisource.org

-

A commonplace book is what a provident poet cannot subsist without, for this proverbial, reason, that "great wits have short memories;" and whereas, on the other hand, poets, being liars by profession, ought to have good memories; to reconcile these, a book of this sort, is in the nature of a supplemental memory, or a record of what occurs remarkable in every day's reading or conversation. There you enter not only your own original thoughts, (which, a hundred to one, are few and insignificant) but such of other men, as you think fit to make your own, by entering them there. For, take this for a rule, when an author is in your books, you have the same demand upon him for his wit, as a merchant has for your money, when you are in his. By these few and easy prescriptions, (with the help of a good genius) it is possible you may, in a short time, arrive at the accomplishments of a poet, and shine in that character[3].

"Nullum numen abest si sit prudentia, is unquestionably true, with regard to every thing except poetry; and I am very sure that any man of common understanding may, by proper culture, care, attention, and labour, make himself whatever he pleases, except a good poet." Chesterfield, Letter lxxxi.

See also: https://en.m.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Works_of_the_Rev._Jonathan_Swift,_Volume_5.djvu/261 as a source

Swift, Jonathan. The Works of the Rev. Jonathan Swift. Edited by Thomas Sheridan and John Nichols. Vol. 5. 19 vols. London: H. Baldwin and Son, 1801.

-

-

billyoppenheimer.com billyoppenheimer.com

-

Oppenheimer, Billy. “The Notecard System: Capture, Organize, and Use Everything You Read, Watch, and Listen To.” Billy Oppenheimer (blog), August 26, 2022. https://billyoppenheimer.com/notecard-system/.

-

Ronald Reagan notecard

-

He has a warehouse of notecards with ideas and stories and quotes and facts and bits of research, which get pulled and pieced together then proofread and revised and trimmed and inspected and packaged and then shipped.

While the ancients thought of the commonplace as a storehouse of value or a treasury, modern knowledge workers and content creators might analogize it to a factory where one stores up ideas in a warehouse space where they can be easily accessed, put into a production line where those ideas can be assembled, revised, proofread, and then package and distributed to consumers (readers).

(summary)

-

In this article, I am going to explain my adapted version of the notecard system.

Note that he explicitly calls out that his is an adapted version of a preexisting thing--namely a system that was taught to Ryan Holiday who was taught by Robert Greene.

Presumably there is both some economic and street cred value for the author/influencer in claiming his precedents.

It's worth noting that he mentions other famous users, though only the smallest fraction of them with emphasis up front on his teachers whose audience he shares financially.

-

The Notecard System

This is almost pitched as a product with the brand name "The Notecard System".

Tags

- commonplace books

- Billy Oppenheimer

- card index as factory space for ideas

- influencers

- Ryan Holiday

- audience

- filing systems

- knowledge workers

- examples

- analogies

- read

- index card based commonplace books

- Billy Oppenheimer's zettelkasten

- index cards

- names

- one liners

- Ronald Reagan

- content creators

- email lists

- references

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.usatoday.com www.usatoday.com

-

"If the Reagans' home in Palisades (Calif.) were burning," Brinkley says, "this would be one of the things Reagan would immediately drag out of the house. He carried them with him all over like a carpenter brings their tools. These were the tools for his trade."

Another example of someone saying that if their house were to catch fire, they'd save their commonplace book (first or foremost).

-

-

www.indiegogo.com www.indiegogo.com

- Oct 2022

-

-

‘What tho’ his head be empty, provided his common-place book be full?’ sneered Jonathan Swift.

-

I feel sympathy for Robert Southey, whose excerpts from his voracious reading were posthumously published in four volumes as Southey’s Common-Place Book. He confessed in 1822 that,Like those persons who frequent sales, and fill their houses with useless purchases, because they may want them some time or other; so am I for ever making collections, and storing up materials which may not come into use till the Greek Calends. And this I have been doing for five-and-twenty years! It is true that I draw daily upon my hoards, and should be poor without them; but in prudence I ought now to be working up these materials rather than adding to so much dead stock.

-

Before the Xerox machine, this was a labour-intensive counsel of perfection; and it is no wonder that many of the great 19th-century historians employed professional copyists.

According to Keith Thomas, "many of the great 19th-century historians employed professional copyists" as a means of keeping up with filing copies of their note slips under multiple subject headings.

-

As the historian Thomas Fuller remarked, ‘A commonplace book contains many notions in garrison, whence the owner may draw out an army into the field on competent warning.’

-

Another help to the memory is the pocketbook in which to enter stray thoughts and observations: what the Elizabethans called ‘tablets’.

Elizabethans called pocketbooks or small notebooks "tablets."

Tags

- commonplace books

- Thomas Fuller

- Jonathan Swift

- collector's fallacy

- copyists

- historians

- published note collections

- armies

- copying

- analogies

- index card based commonplace books

- Keith Thomas

- Robert Southey

- quotes

- note taking

- card index for writing

- pocket books

- writing for understanding

- Xerox

- definitions

- tablets

Annotators

URL

-

-

drummer.this.how drummer.this.how

-

http://drummer.this.how/AndySylvester99/Andy_Zettelkasten.opml

Andy Sylvester's experiment in building a digital zettelkasten using OPML and tagging. Curious to see how it grows and particularly whether or not it will scale with this sort of UI? On first blush, the first issue I see as a reader is a need for a stronger and immediate form of search.

RSS feeds out should make for a more interesting UI for subscribing and watching the inputs though.

-

-

www.indxd.ink www.indxd.inkIndxd1

-

https://www.indxd.ink/

A digital, web-based index tool for your analog notebooks. Ostensibly allows one to digitally index their paper notebooks (page numbers optional).

It emails you weekly text updates, so you've got a back up of your data if the site/service disappears.

This could potentially be used by those who have analog zettelkasten practices, but want the digital search and some back up of their system.

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>sgtstretch </span> in @Gaby @pimoore so a good friend of mine makes [INDXD](https://www.indxd.ink/) which is for indexing analog notebooks and being able to find things. I don't personally use it, but I know @patrickrhone has written about it before. (<time class='dt-published'>10/27/2022 17:59:32</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mI3yiPA6npA

Generally interesting and useful, but is broadly an extended advertisement for JetPens products.

Transparent sticky notes allow one to take notes on them, but the text is still visible through the paper.

One can use separate pages to write notes and then use washi tape to tape the notes to the page in a hinge-like fashion similar to selectively interleaving one's books.

-

-

-

Very nice to differentiate between core notes (notes that we have worked a lot on) and peripheral notes.

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>Very nice to differentiate between core notes (notes that we have worked a lot on) and peripheral notes.

— Bianca Pereira | PKM Coach and Researcher (@bianca_oli_per) October 24, 2022Coming from the Strange New Worlds Plugin, Bianca Pereira defines core notes (those worked on and thus likely of more value) versus peripheral notes.

Core notes have a similar connotation to so-called permanent notes while peripheral notes have connection to fleeting notes, though peripheral notes would seem to have a higher connotation of value than fleeting notes.

Some of this is similar to my commonplacing practice and collection versus my more focused Luhmann-esque zettelkasten practice.

-

-

richardcarter.com richardcarter.com

-

minnstate.pressbooks.pub minnstate.pressbooks.pub

-

I might even say the best books are the best books because they stubbornly defy being reduced to a synopsis and some notes. Another way of saying that is, great books have so much in them that many different people with many different interests can all find something they’ll value in their pages.

This might be said of art, design, or any pursuit. Any design might comprise hundreds of design decisions. The more there are, the more depth to the design, the more facets of the problem space it has examined, the more knowledge it may contain, the more potential to learn.

-

-

laudatortemporisacti.blogspot.com laudatortemporisacti.blogspot.com

-

Laudator Temporis Acti

https://laudatortemporisacti.blogspot.com/

Michael Gilleland is an antediluvian, bibliomaniac, and curmudgeon.

The title of the blog and Gilleland's calling himself a curmudgeon calls to mind Horace...

-

-

www.dla-marbach.de www.dla-marbach.de

-

"In the event of a fire, the black-bound excerpts are to be saved first," instructed the poet Jean Paul to his wife before setting off on a trip in 1812.

Writer Jean Paul on the importance of his Zettelkasten.

-

-

ryanholiday.net ryanholiday.net

-

What if something happened to your box? My house recently got robbed and I was so fucking terrified that someone took it, you have no idea. Thankfully they didn’t. I am actually thinking of using TaskRabbit to have someone create a digital backup. In the meantime, these boxes are what I’m running back into a fire for to pull out (in fact, I sometimes keep them in a fireproof safe).

His collection is incredibly important to him. He states this in a way that's highly reminiscent of Jean Paul.

"In the event of a fire, the black-bound excerpts are to be saved first." —instructions from Jean Paul to his wife before setting off on a trip in 1812 #

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Does anyone else work in project-based systems instead? .t3_y2pzuu._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/m_t_rv_s__n https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/y2pzuu/does_anyone_else_work_in_projectbased_systems/

Historically, many had zettelkasten which were commonplace books kept on note cards, usually categorized by subject (read: "folders" or "tags"), so you're not far from that original tradition.

Similar to your work pattern, you may find the idea of a "Pile of Index Cards" (PoIC) interesting. See https://lifehacker.com/the-pile-of-index-cards-system-efficiently-organizes-ta-1599093089 and https://www.flickr.com/photos/hawkexpress/albums/72157594200490122 (read the descriptions of the photos for more details; there was also a related, but now defunct wiki, which you can find copies of on Archive.org with more detail). This pattern was often seen implemented in the TiddlyWiki space, but can now be implemented in many note taking apps that have to do functionality along with search and tags. Similarly you may find those under Tiago Forte's banner "Building a Second Brain" to be closer to your project-based/productivity framing if you need additional examples or like-minded community. You may find that some of Nick Milo's Linking Your Thinking (LYT) is in this productivity spectrum as well. (Caveat emptor: these last two are selling products/services, but there's a lot of their material freely available online.)

Luhmann changed the internal structure of his particular zettelkasten that created a new variation on the older traditions. It is this Luhmann-based tradition that many in r/Zettelkasten follow. Since many who used the prior (commonplace-based) tradition were also highly productive, attributing output to a particular practice is wrongly placed. Each user approaches these traditions idiosyncratically to get them to work for themselves, so ignore naysayers and those with purist tendencies, particularly when they're new to these practices or aren't aware of their richer history. As the sub-reddit rules indicate: "There is no [universal or orthodox] 'right' way", but you'll find a way that is right for you.

-

-

delong.typepad.com delong.typepad.com

-

Francis Bacon once remarked that "some booksare to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to bechewed and digested."

-

-

commonplaces.io commonplaces.io

-

via https://www.reddit.com/r/commonplacebook/

If you want to try commonplacing digitally, u/Citrie is developing commonplaces.io — if you try it, please send them any feedback you have!

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Check out the Zettelkasten (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettelkasten). It may be similar to what you're thinking of. I use a digital one (Foam), and it's absolutely awesome. It's totally turned how I do my work for school on its head.

reply to https://www.reddit.com/user/kf6gpe/

Thanks. Having edited large parts of that page, and particularly the history pieces, I'm aware of it. It's also why I'm asking for actual examples of practices and personal histories, especially since many in this particular forum appear to be using traditional notebook/journal forms. :)

Did you come to ZK or commonplacing first? How did you hear about it/them? Is your practice like the traditional commonplacing framing, closer to Luhmann's/that suggested by zettelkasten.de/Ahrens, or a hybrid of the two approaches?

-

Index cards for commonplacing?

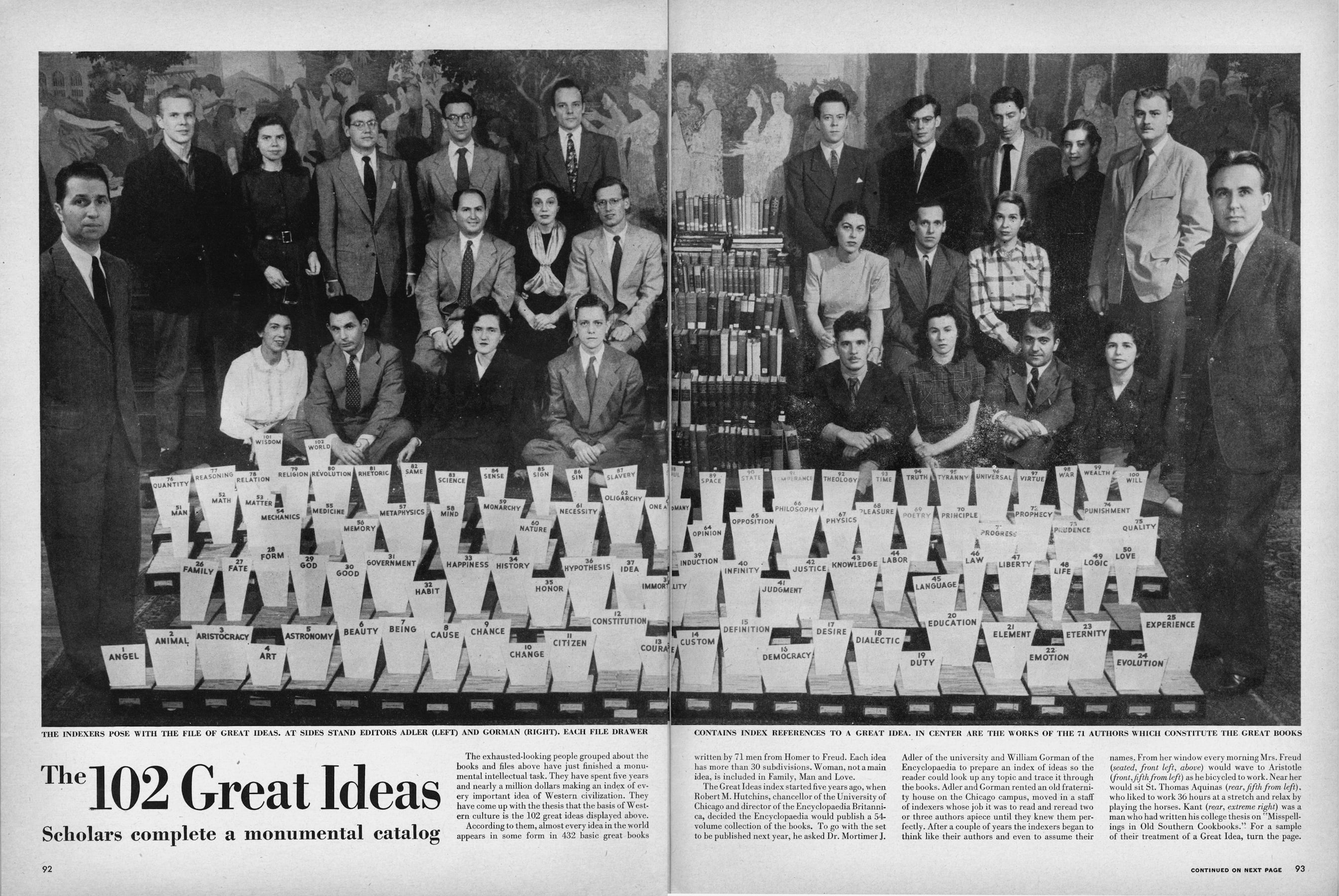

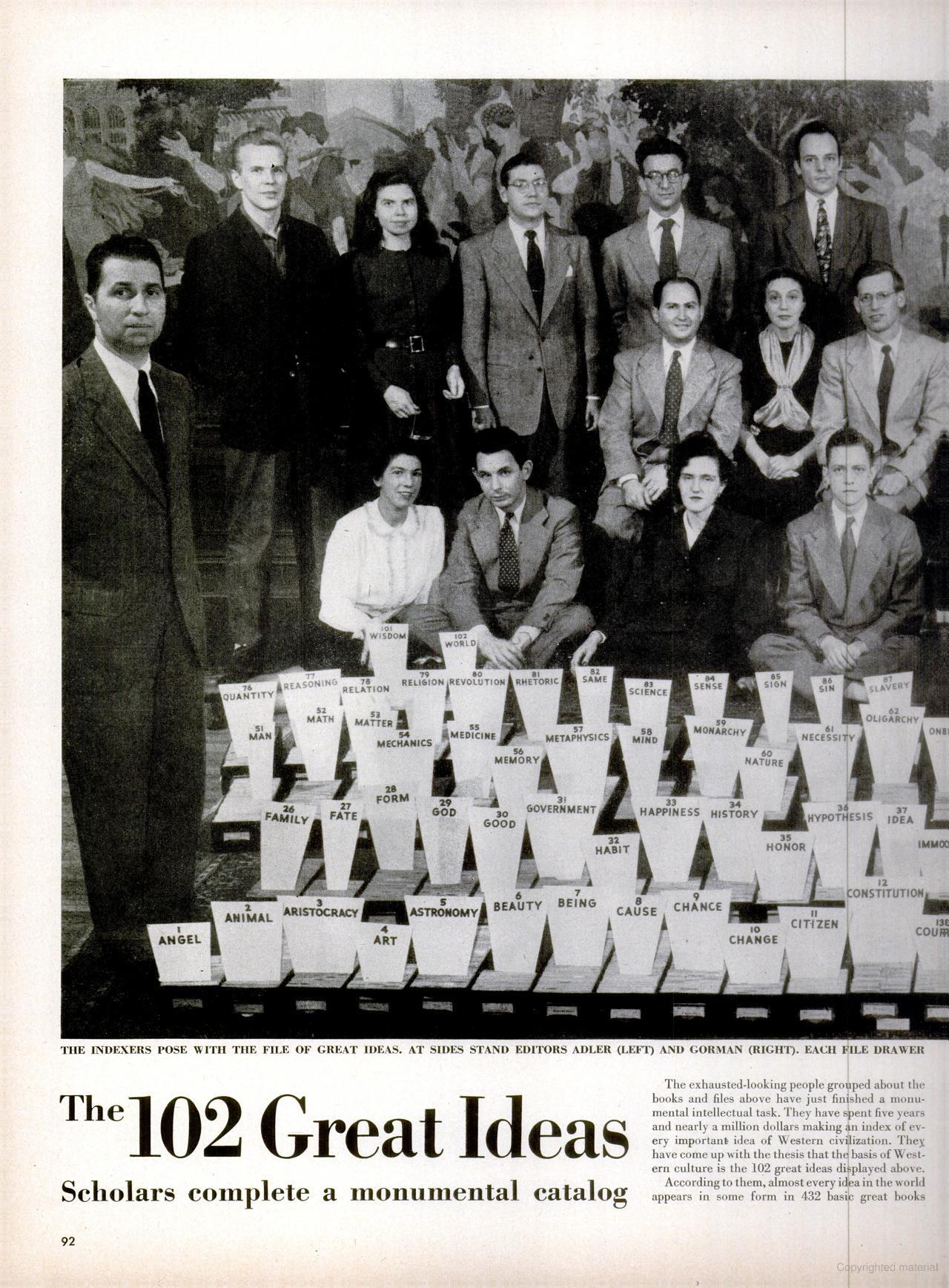

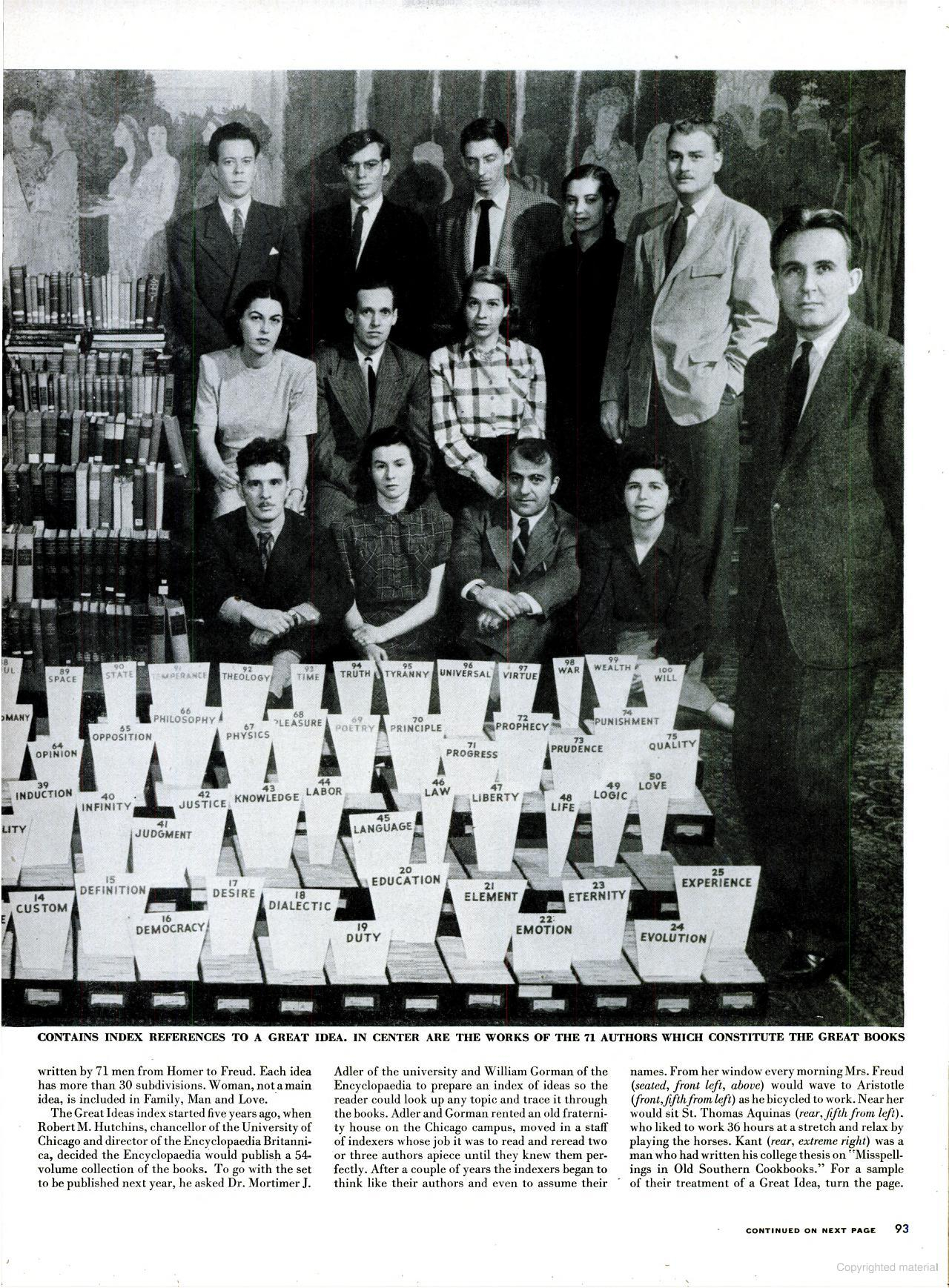

I know that Robert Greene and Ryan Holiday have talked about their commonplace methods using index cards before, and Mortimer J. Adler et al. used index cards with commonplacing methods in their Great Books/Syntopicon project, but is anyone else using this method? Where or from whom did you learn/hear about using index cards? What benefits do you feel you're getting over a journal or notebook-based method? Mortimer J. Adler smoking a pipe amidst a sea of index cards in boxes with 102 topic labels (examples: Law, World, Love, Life, Being, Sin, Art, Citizen, Change, etc.)

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Underlining Keyterms and Index Bloat .t3_y1akec._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

Hello u/sscheper,

Let me start by thanking you for introducing me to Zettelkasten. I have been writing notes for a week now and it's great that I'm able to retain more info and relate pieces of knowledge better through this method.

I recently came to notice that there is redundancy in my index entries.

I have two entries for Number Line. I have two branches in my Math category that deals with arithmetic, and so far I have "Addition" and "Subtraction". In those two branches I talk about visualizing ways of doing that, and both of those make use of and underline the term Number Line. So now the two entries in my index are "Number Line (Under Addition)" and "Number Line (Under Subtraction)". In those notes I elaborate how exactly each operation is done on a number line and the insights that can be derived from it. If this continues, I will have Number Line entries for "Multiplication" and "Division". I will also have to point to these entries if I want to link a main note for "Number Line".

Is this alright? Am I underlining appropriately? When do I not underline keyterms? I know that I do these to increase my chances of relating to those notes when I get to reach the concept of Number Lines as I go through the index but I feel like I'm overdoing it, and it's probably bloating it.

I get "Communication (under Info. Theory): '4212/1'" in the beginning because that is one aspect of Communication itself. But for something like the number line, it's very closely associated with arithmetic operations, and maybe I need to rethink how I populate my index.

Presuming, since you're here, that you're creating a more Luhmann-esque inspired zettelkasten as opposed to the commonplace book (and usually more heavily indexed) inspired version, here are some things to think about:<br /> - Aren't your various versions of number line card behind each other or at least very near each other within your system to begin with? (And if not, why not?) If they are, then you can get away with indexing only one and know that the others will automatically be nearby in the tree. <br /> - Rather than indexing each, why not cross-index the cards themselves (if they happen to be far away from each other) so that the link to Number Line (Subtraction) appears on Number Line (Addition) and vice-versa? As long as you can find one, you'll be able to find them all, if necessary.

If you look at Luhmann's online example index, you'll see that each index term only has one or two cross references, in part because future/new ideas close to the first one will naturally be installed close to the first instance. You won't find thousands of index entries in his system for things like "sociology" or "systems theory" because there would be so many that the index term would be useless. Instead, over time, he built huge blocks of cards on these topics and was thus able to focus more on the narrow/niche topics, which is usually where you're going to be doing most of your direct (and interesting) work.

Your case sounds, and I see it with many, is that your thinking process is going from the bottom up, but that you're attempting to wedge it into a top down process and create an artificial hierarchy based on it. Resist this urge. Approaching things after-the-fact, we might place information theory as a sub-category of mathematics with overlaps in physics, engineering, computer science, and even the humanities in areas like sociology, psychology, and anthropology, but where you put your work on it may depend on your approach. If you're a physicist, you'll center it within your physics work and then branch out from there. You'd then have some of the psychology related parts of information theory and communications branching off of your physics work, but who cares if it's there and not in a dramatically separate section with the top level labeled humanities? It's all interdisciplinary anyway, so don't worry and place things closest in your system to where you think they fit for you and your work. If you had five different people studying information theory who were respectively a physicist, a mathematician, a computer scientist, an engineer, and an anthropologist, they could ostensibly have all the same material on their cards, but the branching structures and locations of them all would be dramatically different and unique, if nothing else based on the time ordered way in which they came across all the distinct pieces. This is fine. You're building this for yourself, not for a mass public that will be using the Dewey Decimal System to track it all down—researchers and librarians can do that on behalf of your estate. (Of course, if you're a musician, it bears noting that you'd be totally fine building your information theory section within the area of "bands" as a subsection on "The Bandwagon". 😁)

If you overthink things and attempt to keep them too separate in their own prefigured categorical bins, you might, for example, have "chocolate" filed historically under the Olmec and might have "peanut butter" filed with Marcellus Gilmore Edson under chemistry or pharmacy. If you're a professional pastry chef this could be devastating as it will be much harder for the true "foodie" in your zettelkasten to creatively and more serendipitously link the two together to make peanut butter cups, something which may have otherwise fallen out much more quickly and easily if you'd taken a multi-disciplinary (bottom up) and certainly more natural approach to begin with. (Apologies for the length and potential overreach on your context here, but my two line response expanded because of other lines of thought I've been working on, and it was just easier for me to continue on writing while I had the "muse". Rather than edit it back down, I'll leave it as it may be of potential use to others coming with no context at all. In other words, consider most of this response a selfish one for me and my own slip box than as responsive to the OP.)

Tags

- information theory

- commonplace books vs. zettelkasten

- reply

- Claude Shannon

- Niklas Luhmann's index

- Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten

- zettelkasten

- Universal Decimal Classification

- indices

- bottom-up vs. top-down

- examples

- Dewey Decimal System

- multi-disciplinary research

- The Bandwagon

- hierarchies

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.greyroom.org www.greyroom.org

-

http://www.greyroom.org/issues/60/20/the-dialectic-of-the-university-his-masters-voice/

“The Indexers pose with the file of Great Ideas. At sides stand editors [Mortimer] Adler (left) and [William] Gorman (right). Each file drawer contains index references to a Great Idea. In center are the works of the 71 authors which constitute the Great Books.” From “The 102 Great Ideas: Scholars Complete a Monumental Catalog,” Life 24, no. 4 (26 January 1948). Photo: George Skadding.