"Екатерина Шульман: Практический Нострадамус, или 12 умственных привычек, которые мешают нам предвидеть будущее". vedomosti/ (in Russian). Retrieved 24 June 2021.

A Note on the Cargo Cult of Zettelkasten

Modern cargo cults can be seen in many technology and productivity spaces where people are pulled in by exaggerated (or sometimes even real claims) of productivity or the general "magic" of a technology or method.

An example is Niklas Luhmann's use of his zettelkasten which has created a cargo cult of zettelkasten aspirants and users who read one or more of the short one page blog posts about his unreasonable productivity and try to mimic it without understanding the system, how it works, or how to make it work for them. They often spend several months collecting notes, and following the motions, but don't realize the promised gains and may eventually give up, sometimes in shame (or as so-called "rubbish men") while watching others still touting its use.

To prevent one's indoctrination into the zettelkasten cult, I'll make a few recommendations:

Distance yourself from the one or two page blog posts or the breathless YouTube delineations. Ask yourself very pointedly: what you hope to get out of such a process? What's your goal? Does that goal align with others' prior uses and their outcomes?

Be careful of the productivity gurus who are selling expensive courses and whose focus may not necessarily be on your particular goals. Some are selling very pointed courses, which is good, while others are selling products which may be so broad that they'll be sure to have some success stories, but their hodge-podge mixture of methods won't suit your particular purpose, or worse, you'll have to experiment with pieces of their courses to discover what may suit your modes of working and hope they'll suffice in the long run. Some are selling other productivity solutions for task management like getting things done (GTD) or bullet journals, which can be a whole other cargo cults in and of themselves. Don't conflate these![^1] The only thing worse than being in a cargo cult is being in multiple at the same time.

If you go the digital route, be extremely wary of shiny object syndrome. Everyone has a favorite tool and will advocate that it's the one you should be using. (Often their method of use will dictate how much they love it potentially over and above the affordances of the tool itself.) All of these tools can be endlessly configured, tweaked, or extended with plugins or third party services. Everyone wants to show you their workflow and set up, lots of which is based on large amounts of work and experimentation. Ignore 99.999% of this. Most tools are converging to a similar feature set, so pick a reasonable one that seems like it'll be around in 5 years (and which has export, just in case). Try out the very basic features for several months before you change anything. Don't add endless plugins and widgets. You're ultimately using a digital tool to recreate the functionality of index cards, a pencil, and a box. How complicated should this really be? Do you need to spend hundreds of hours tweaking your system to save yourself a few minutes a year? Be aware that far too many people touting the system and marketers talking about the tools are missing several thousands of years of uses of some of these basic literacy-based technologies. Don't join their island cult, but instead figure out how the visiting culture has been doing this for ages.[^2] Recall Will Hunting's admonition against cargo cults in education: “You wasted $150,000 on an education you coulda got for $1.50 in late fees at the public library.”[^3]

Most people ultimately realize that the output of their own thinking is only as good as the inputs they're consuming. Leverage this from the moment you begin and ignore the short bite-sized advice for longer form or older advice from those with experience. You're much more likely to get more long term value out of reading Umberto Eco or Mortimer J. Adler & Charles van Doren[^4] than you are an equivalent amount of time reading blog posts, watching YouTube videos, or trolling social media like Reddit and Twitter.

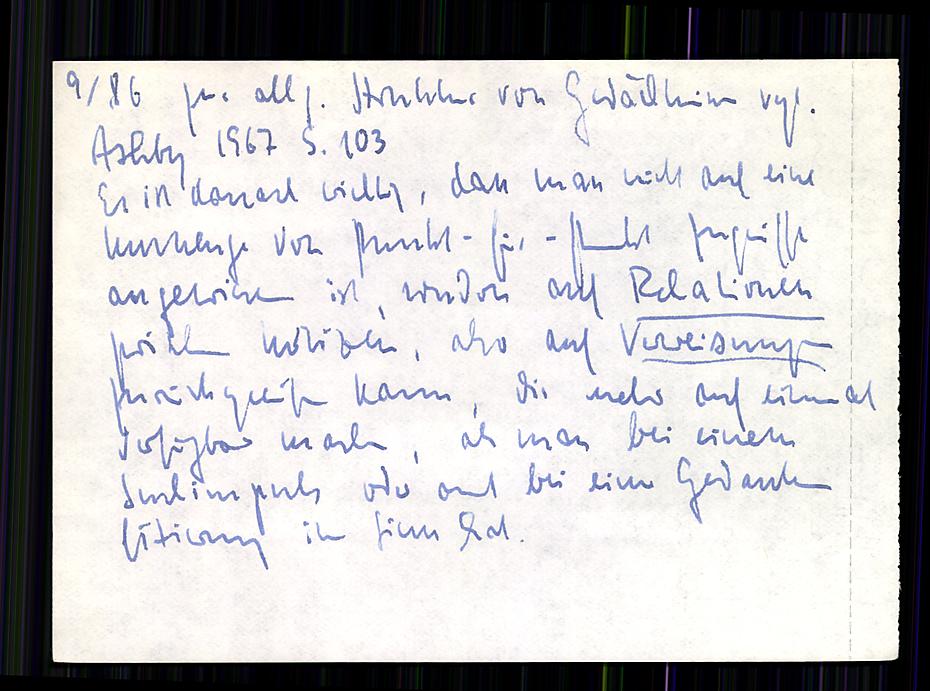

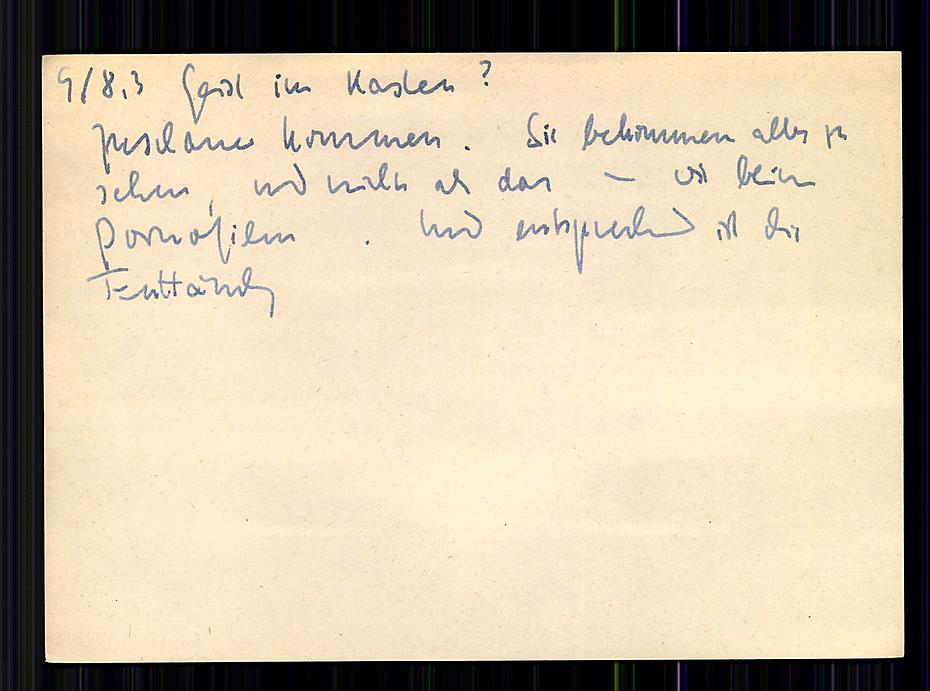

Realize that reaching your goal is going to take honest-to-goodness actual work, though there is potential for fun. No matter how shiny or optimized your system, you've still got to do the daily work of reading, watching, listening and using it to create anything. Focus on this daily work and don't get sidetracked by the minutiae of trying to shave off just a few more seconds.[^5] In short, don't get caught up in the "productivity porn" of it all. Even the high priest at whose altar they worship once wrote on a slip he filed:

"A ghost in the note card index? Spectators visit [my office to see my notes] and they get to see everything and nothing all at once. Ultimately, like having watched a porn movie, their disappointment is correspondingly high."

—Niklas Luhmann. <small>“Geist im Kasten?” ZKII 9/8,3. Niklas Luhmann-Archiv. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8-3_V. (Personal translation from German with context added.)</small>

[^1] Aldrich, Chris. “Zettelkasten Overreach.” BoffoSocko (blog), February 5, 2022. https://boffosocko.com/2022/02/05/zettelkasten-overreach/.

[^2]: Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. Yale University Press, 2010. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300165395/too-much-know.

[^3]: Good Will Hunting. Miramax, Lawrence Bender Productions, 1998.

[^4]: Adler, Mortimer J., and Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. Revised and Updated edition. 1940. Reprint, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972.

[^5]: Munroe, Randall. “Is It Worth the Time?” Web comic. xkcd, April 29, 2013. https://xkcd.com/1205/.

Recommended resources

Choose only one of the following and remember you may not need to read the entire work:

Ahrens, Sönke. How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers. Create Space, 2017.

Allosso, Dan, and S. F. Allosso. How to Make Notes and Write. Minnesota State Pressbooks, 2022. https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/write/.

Bernstein, Mark. Tinderbox: The Tinderbox Way. 3rd ed. Watertown, MA: Eastgate Systems, Inc., 2017. http://www.eastgate.com/Tinderbox/TinderboxWay/index.html.

Dow, Earle Wilbur. Principles of a Note-System for Historical Studies. New York: Century Company, 1924.

Eco, Umberto. How to Write a Thesis. Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina. 1977. Reprint, Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2015. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/how-write-thesis.

Gessner, Konrad. Pandectarum Sive Partitionum Universalium. 1st Edition. Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1548.

Goutor, Jacques. The Card-File System of Note-Taking. Approaching Ontario’s Past 3. Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1980. http://archive.org/details/cardfilesystemof0000gout.

Sertillanges, Antonin Gilbert, and Mary Ryan. The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods. First English Edition, Fifth printing. 1921. Reprint, Westminster, MD: The Newman Press, 1960. http://archive.org/details/a.d.sertillangestheintellectuallife.

Webb, Sidney, and Beatrice Webb. Methods of Social Study. London; New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1932. http://archive.org/details/b31357891.

Weinberg, Gerald M. Weinberg on Writing: The Fieldstone Method. New York, N.Y: Dorset House, 2005.

© Alexander Kluge/ Universität Bielefeld*

© Alexander Kluge/ Universität Bielefeld* Niklas Luhmann, Zettelkasten II,

Niklas Luhmann, Zettelkasten II,