RRID:AB_2337541

DOI: 10.1080/19420862.2025.2570748

Resource: (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs Cat# 109-005-098, RRID:AB_2337541)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:AB_2337541

RRID:AB_2337541

DOI: 10.1080/19420862.2025.2570748

Resource: (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs Cat# 109-005-098, RRID:AB_2337541)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:AB_2337541

AB_10951811

DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113776

Resource: (MBL International Cat# M180-3, RRID:AB_10951811)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:AB_10951811

Length of Stay (LOS)

uitbreiden met huidig gemiddelde 3 maanden

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Rovira, et al., aim to characterize immune cells in the brain parenchyma and identify a novel macrophage population referred to as "dendritic-like cells". They use a combination of single-cell transcriptomics, immunohistochemistry, and genetic mutants to conclude the presence of this "dendritic-like cell" population in the brain. The strength of this manuscript is the identification of dendritic cells in the brain, which are typically found in the meningeal layers and choroid plexus. In addition, Rovira, et al., findings are supported by the findings of the Wen lab and a recent Cell Reports paper. Congratulations on the nice work!

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Weaknesses:

While scRNA-seq data clearly revealed different subsets of microglia, macrophages, and DCs in the brain, it remains somewhat challenging to distinguish DC-like cells from P2ry12- macrophages by immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.

Indeed, in flow cytometry analyses of adult brain samples, the p2ry12<sup>-</sup>; mpeg1<sup>+</sup> fraction could, in theory, encompass not only DC-like cells but also other macrophage subsets, as well as B cells, since B cells have been reported to express mpeg1 in zebrafish (Ferrero et al., 2020; Moyse et al., 2020). Nevertheless, our data strongly indicate that within the brain parenchyma, DC-like cells represent the predominant component of this population. This conclusion is supported by the pronounced reduction of p2ry12<sup>-</sup>; mpeg1<sup>+</sup> cells in brain sections from ba43 mutants, in which DC development is impaired. Currently, further phenotypic resolution is constrained by the limited availability of zebrafish-specific antibodies and the restricted palette of fluorescent reporter lines capable of distinguishing MNP subsets. We anticipate that future efforts, including the generation of novel transgenic lines informed by our dataset (initiatives already underway in our group), will enable more precise discrimination among these distinct subsets.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

A weakness of this study is that it is mainly based on FACS sorting, which might modify the proportion of different subtypes.

We agree that reliance solely on FACS could potentially introduce biases in the proportions of different subtypes. To minimize this concern, we complemented our flow cytometry data with quantification performed directly on brain sections using immunohistochemistry. This approach allowed us to validate cell population distributions in situ, thereby confirming that the trends observed by FACS accurately reflect the cellular composition of microglia and DC-like cells within the brain parenchyma.

Reviewer#3 (Public Review):

A weakness is the lack of specific reporters or labeling of this dendritic cell population using specific genes found in their single-cell dataset. Additionally, it is difficult to remove the meningeal layers from the brain samples and thus can lead to confounding conclusions. Overall, I believe this study should be accepted contingent on sufficient labeling of this population and addressing comments.

While the generation of DC-like specific transgenic lines is indeed a promising direction (and such efforts are currently underway in our group), creating and validating these lines is time-consuming. Importantly, although these additional tools will be valuable for future functional investigations, we believe they would not impact the main conclusions or core message of our current work, where we already provide detailed spatial information on DC-like cells, and we demonstrated their lineage identity through the use of our newly generated batf3 mutant line.

Recommendations for the authors:

Major Comments:

The authors should discuss another recent report demonstrating DCs in the zebrafish brain, which also developed independently of Csf1ra, and compare the two datasets (Zhou et al. Cell reports, 2023).

Thank you for highlighting the study by Zhou et al., which offers complimentary insight into the dendritic cell population in the zebrafish brain. We note that in this work, the authors reclassify ccl34b.1<sup>-</sup> mpeg1<sup>+</sup> brain-resident cells as conventional DCs, thus revising their earlier interpretation of these cells as microglia (Wu et al., 2020). This shift in interpretation is based on their transcriptional comparison between the previously characterized ccl34b.1<sup>-</sup> mpeg1<sup>+</sup> population and a new dataset of brain

mpeg1<sup>+</sup> cells. This updated classification aligns closely with our findings. Given that our data already demonstrate the equivalence between the DC-like cells described in our study and the ccl34b.1<sup>-</sup> mpeg1<sup>+</sup> population, repeating a direct transcriptional comparison would be redundant. We have now included a discussion of this work in the revised manuscript. Specifically, we have added the following sentences in the discussion: “Importantly, since the submission of our manuscript, the Wen lab published an independent study in which they now reclassify the ccl34b.1<sup>-</sup> mpeg1<sup>+</sup> cells in the zebrafish brain as cDCs, revising their earlier interpretation of these cells as microglia (Zhou et al., 2023)”.

Data reported in Figure 5 should be quantified (cell numbers, how many brains analyzed).

Thank you for this comment. We would like to clarify that the primary purpose of Figure 5 (and Figure 5 supplement 1) is to provide an initial qualitative overview of the different MNP subsets present in the adult brain, using the currently available transgenic and immunohistochemical tools. These descriptive analyses were instrumental in identifying the most reliable combination, namely the Tg(p2ry12:p2ry12GFP; mpeg1.1:mCherry) double transgenic line in conjunction with L-plastin immunostaining, to distinguish microglia from other parenchymal MNPs. Quantitative analyses using this optimized strategy are presented in Figure 7 (Figure 7 supplement 1), where we systematically enumerate the different MNPs. We therefore believe that performing additional quantification in Figure 5 would be redundant with the more robust data already shown in Figure 7. As requested, we have now included in the Figure 5 legend that images are representative of brain tissue sections from 2-3 fish.

The title mentions an "atlas", but there is no searchable database or website associated with the paper. Please provide one.

We agree and fully support the importance of data accessibility. To facilitate use of our dataset by the scientific community, we have developed a user-friendly, searchable web interface that allows users to explore gene expression pacerns within our dataset. This website is available at https://scrna-analysis zebrafish.shinyapps.io/scatlas/

This information has now been included in the “Data availability statement” section of the manuscript.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Specific comments:

The authors should discuss another recent report demonstrating DCs in the zebrafish brain, which also developed independently of Csf1ra, and compare the two datasets (Zhou et al. Cell reports, 2023).

Thank you for this suggestion. Please refer to our response in the major comments section, where we address this point in detail.

Within macrophages, the authors identified 5 clusters including 4 microglia clusters and 1 MF cluster (Figure 4). Does the laUer relate to 'BAMs' and express markers previously described in murine BAMs, including Lyve1, CD206, etc.? Or to monocytes? By flow cytometry, monocytes were detected (Figure 1B), but not by scRNA-seq.

You have raised an important point here. As described in lines 197-202 (“results” section), the cells in the MF cluster exhibit a macrophage identity, based on their expression of classical macrophage markers such as marco, mfap4 or csf1ra. However, we were unable to confidently annotate this cluster more specifically. We also considered whether this population might resemble mammalian BAMs or monocytes, cell types that, to our knowledge, have not yet been clearly identified in zebrafish. However, orthologous markers typically associated with murine BAMs were not detected (lyve1) or not specifically enriched (mrc1a/mrc1b) in the MF cluster (see below). Based on these findings, we can only cautiously propose that this cluster may represent blood-derived macrophages and / or monocytes.

To further address your suggestion, we performed a cell type enrichment analysis using the marker genes of the MF cluster, following the same strategy as for the microglia and DC-like clusters presented in Figure 4 supplement 2 C,D. This analysis revealed significant for “monocytes” and “macrophages”, further supporting a general monocytic/macrophage identity (see below). At present, further characterization of this cluster is limited by the lack of zebrafish-specific antibodies and the restricted palette of fluorescent reporter lines that distinguish among MNP subsets. We anticipate that future studies, including the development of new transgenic lines guided by our dataset, will allow for a more precise analysis of this distinct population.

Author response image 1.

Do all 4 DC clusters identified by scRNA-seq represent cDC1s? or are there also cDC2s, and cDC3s present?

In our analyses, the four dendritic cell clusters identified by scRNA-seq (DC1-DC4) exhibit transcriptional profiles consistent with a conventional type 1 dendritic cell (cDC1) identity. These clusters uniformly express hallmark cDC1-associated genes, while lacking expression of markers typically associated with mammalian cDC2 or plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs). For instance, irf4, a key transcription factor required for cDC2 development, is not detected in our dataset. Similarly, we do not observe expression of genes characteristic of pDCs.

That said, the absence of cDC2 or pDC-like signatures in our dataset does not rule out the presence of these populations in zebrafish.

While they show that DC-like cells did not express Csf1rb (Figure 4D) or other macrophage/microglia genes, DC-like cells were affected in the Csf1rb mutants and in double mutants, demonstrating that their development depends on Csf1rb signaling, as known for macrophages but not DCs. Can the authors discuss this in more detail with regard to DC differentiation/precursors?

Thank you for pointing this out. As previously demonstrated, CSF1R signaling in zebrafish is more complex than in mammals, due to the presence of two paralogs, csf1ra and csf1rb, which exhibit partially non-overlapping functions (Ferrero et al., 2021). We and others have shown that csf1rb signaling is implicated in the regulation of definitive hematopoiesis, particularly in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC)-derived myelopoiesis. Although the developmental origin of zebrafish brain DC-like cells remains uncharacterized, their reduced numbers in the csf1rb mutant, despite their lack of csf1rb expression, supports the current model in which csf1rb acts at the progenitor level, promoting myeloid lineage commitment. According to this, csf1rb disruption affects the differentiation of multiple myeloid subsets, which likely include DC-like cells. We have developed this point in the discussion section (lines 502506).

Do the DCs express Csf1ra?

Csf1ra transcripts are not found in DCs in our dataset. As shown below, csf1ra expression is restricted to the microglia and macrophage clusters. These observations are in line with those made by Zhou et al., 2023.

Author response image 2.

Fig. 5, the number of brains analyzed should be added, and also quantifications of cell numbers included. It is mentioned (line 260) that P2ry12GFP+mpeg1mCherry+ microglia are abundant across brain regions while P2ry12GFP- mpeg1mCherry+ cells particularly localize in the ventral part of the posterior brain parenchyma. It would be nice if images of the different brain regions were provided.

Regarding the quantification, we refer to our response in the major comments section, where we explain that detailed quantification of microglia and other MNP subsets is provided in Figure 7, using a more refined strategy for distinguishing cell types.

As requested, we have now included representative sections from the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain of adult Tg(mhc2dab:GFP; cd45:DsRed) fish. These images illustrate the spatial distribution of DC-like cells across brain regions. Notably, DC-like cells are most abundant in the ventral areas of the midbrain and hindbrain, and are also present in the posterior telencephalon, particularly concentrated in the region of the commissura anterior. This regional annotation is based on the zebrafish brain atlas by Wullimann et al., 1996 (Neuroanatomy of the zebrafish brain, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-8979-7).

These additional images have been included in Figure 5 Supplement 1 (A-E).

It is sometimes not evident whether the Pr2y12- cells included DC-like cells and macrophages, which should be discussed.

Thank you for bringing this to our attention. Upon review, we agree this point required clearer explanation throughout the text, particularly beginning with the description of putative DC-like cells in Figure 5. We have now revised the manuscript to improve clarity and becer guide readers through the phenotypic identification of DC-like cells using the Tg(p2ry12:p2ry12-GFP;mpeg1:mCherry) line. Specifically, we have modified the titles in the results section from page 5 to page 9, so that readers can more easily follow the step-by-step approach we used to distinguish DC-like cells from microglia.

To directly address your comment: the p2ry12<sup>-</sup>; mpeg1<sup>+</sup> fraction may, in theory, include not only DC-like cells but also other macrophage subsets and B cells, as B cells have been shown to express mpeg1 in zebrafish (Ferrero et al., 2020; Moyse et al., 2020). Nevertheless, our data strongly indicate that within the brain parenchyma, DC-like cells represent the predominant component of this population. This conclusion is supported by the pronounced reduction of p2ry12<sup>-</sup>; mpeg1<sup>+</sup> cells in brain sections from ba43 mutants, in which DC development is impaired.

We have revised the text accordingly to clarify this point in the results section of the manuscript (line 355).

For example, the DC-like cell population in Figure 6C appears to include two populations of cells. Thus, it is unclear whether the sorted mhc2dab:GFP+;CD45:DsRedhi population for bulk-seq also contains the MF population identified in Fig. 2.

Thank you for this thoughtful observation. During the course of this study, we indeed considered how best to isolate non-microglial macrophages in order to specifically recover the MF population identified in our scRNA-seq analysis. However, with the current repertoire of fluorescent transgenic zebrafish lines, it remains technically challenging to selectively isolate non-microglial macrophages from the adult brain. As a result, the mhc2dab:GFP<sub>+</sub>; cd45:DsRedhi sorted population used for bulk RNA-seq may indeed include a mixture of DC-like and other mononuclear phagocytes, potentially the MF population. In contrast, our data demonstrate that the Tg(p2ry12:p2ry12-GFP) line provides a more selective tool for isolating microglia, minimizing contamination from other mononuclear phagocyte subsets.

In Figure 7, a reduction of GFP-mpeg+ cells can be seen in baf3 mutants. Could the remaining cells be the (non-microglia) macrophages? Or in Figure 8, could the remaining P2ry12GFP-Lcp1+ cells in Irf8 mutants be macrophages?

Indeed, we believe it is likely that the remaining mpeg1<sup>+</sup> cells observed in ba43 mutants include non-microglial macrophages and/or B cells, as we and others previously showed that zebrafish B cells express mpeg1.1 transcripts and are labeled in the mpeg1.1 reporters (Ferrero et al., 2020). This interpretation is further supported by the observation that the reduction in mepg1+ cells is more pronounced in brain sections than in flow cytometry samples, where non-parenchymal mpeg+ cells, such as peripheral macrophages or B cells, are likely enriched. To explore this possibility, we attempted to assess the expression of MF- and B cell-specific markers in the remaining mpeg1+ population isolated from ba43 mutants. However, due to the very low numbers of cells recovered per animal, we were limited to analyzing only a few markers. Despite multiple attempts, qPCR analyses proved unconclusive, likely due to low transcript abundance. We thank you for your understanding of the technical limitations that currently prevent a more definitive characterization of these remaining cells.

Regarding the irf8 mutants (Figure 8), irf8 is a well-established master regulator of mononuclear phagocyte development. In mice, deficiency results in developmental defects and functional impairments across multiple myeloid lineages, including microglia, which exhibit reduced density (Kierdorf et al., 2013) and an immature phenotype (Vanhove and al., 2019). Similarly, in zebrafish, irf8 mutants show abnormal macrophage development, with an accumulation of immature and apoptotic cells during embryonic and larval stages (Shiau et al., 2014). Based on these findings, it is plausible that the residual p2ry12:GFP<sup>-</sup> Lcp1<sup>+</sup> cells observed in the irf8 mutant brains represent immature or arrested mononuclear phagocytes, possibly including both microglia and DC-like cells. This is supported by their distinct morphology and specific localization along the ventricle borders. However, as previously noted, our current tools do not permit to conclusively identify these cells.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

A few sentences are not easy to understand for a "non zebrafish specialist".

(1) Page 3 line 111 The sentence "Interestingly, analyses of brain cell suspensions from double transgenics showed p2ry12:GFP+ microglia accounted for half of cd45:DsRed+ cells (50.9 % {plus minus} 2.9; n=4) (Figure 1D,E). Considering that mpeg1:GFP+ cells comprised ~75% of all leukocytes, these results indicated that approximately 25% of brain mononuclear phagocytes do not express the microglial p2ry12:GFP+ transgene." is not clear. This point is significant and deserves a more detailed explanation.

We apologize for the lack of clarity in this section. The quantification presented in Figure 1 refers specifically to cd45:Dsred<sup>+</sup> leukocytes, meaning that the reported percentages of p2ry12:GFP<sup>+</sup> and mpeg1:GFP<sup>+</sup> cells are calculated relative to the total cd45+ population (defined as 100%). Specifically, we observed that approximately 51% of all cd45+ cells were p2r12:GFP<sup>+</sup> microglia, while around ti5% were mpeg1:GFP<sup>+</sup>. From these values, we infer that about 25% of mpeg1:GFP<sup>+</sup> leukocytes do not express the p2ry12:GFP transgene and therefore likely represent non-microglial mononuclear phagocytes. We agree that this distinction is important and have revised the text accordingly to clarify the interpretation for readers who may be less familiar with zebrafish transgenic lines or gating strategies. See page 3, lines 107 117.

(2) Line 522; Like human and mouse ILC2s, "these cells do not express the T cell receptor cd4-1" is confusing (T cell receptor should be reserved to the ag specific TCR). Also, was TCR isotypes expression analyzed (and how was genome annotation used in this case ?)

Thank you for this insightful comment. We agree that the term “T cell receptor” should be used specifically to refer to antigen-specific TCRs, and we have revised the discussion accordingly to avoid any confusion. Regarding your question on the analysis of TCR isotype expression and the use of genome annotation: due to technical limitations, we did not pursue TCR isotype-level analysis in this study. Instead, we relied on established markers such as cd4-1 and cd8a to distinguish T cell populations, acknowledging that cd4-1 is not expressed by ILC2-like cells in our dataset. We have clarified these points in the relevant sections of the manuscript (see lines 168 and 535)

The analysis of single-cell data might be more detailed, with more explanation about possible doublet identification and normalization procedures.

Thank you for highlighting the need for additional clarity regarding our scRNA-seq analysis.

As noted in the Seurat tutorial, “cell doublets or multiplets often exhibit abnormally high gene count” (https://sa7jalab.org/seurat/archive/v3.0/pbmc3k_tutorial). To evaluate this, we performed a dedicated doublet detection analysis using the scDblFinder R package (https://rdrr.io/bioc/scDblFinder/f/vigneces/2_scDblFinder.Rmd). Our results indicated that the proportion of predicted doublets is low (see Figure below), and when present, these doublets are distributed among the different clusters. This contrasts with the typical clustering of doublets into discrete groups and indicates that our single-cell sequencing workflow was sufficiently robust to predominantly capture singlets.

Regarding normalization, we have clarified this in the manuscript. Briefly, single-cell data were normalized using Seurat’s SCTransform method with the following custom parameters: “variable.features.n=4000 and return.only.var.genes=F”. These settings are now clearly described to ensure reproducibility.

Author response image 3.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Major issues

Though baf3 mutants were generated the manuscript will greatly benefit from in situ labeling by RNAscope or the generation of transgenic reporters to conclusively localize this dendritic cell population and address any potential contamination issues.

We thank you for this constructive suggestion. We agree that in situ labeling approaches such as RNAscope would offer valuable complementary insights. In our current study, however, we already provide detailed spatial information on DC-like cells, and we demonstrated their lineage identity through the use of our newly generated batf3 mutant line.

To address concerns regarding potential contamination, we have carefully analyzed more than two dozens adult brains to date and consistently observed abundant DC-like cells within the brain parenchyma, exhibiting a reproducible and specific spatial distribution, as described in the manuscript. This consistent localization across multiple samples strongly supports the genuine presence of these cells in the brain rather than artifactual contamination.

While the generation of DC-like specific transgenic lines is indeed a promising direction (and such efforts are currently underway in our group) we note that creating and validating these lines is time-consuming and falls beyond the scope of the present study. Importantly, although these additional tools will be valuable for future functional investigations, we believe they would not impact the main conclusions or core message of our current work.

The morphological characterization of CD45:DsRed+ macrophages stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa has been previously reported in the paper, "Characterization of the mononuclear phagocyte system in the zebrafish" Wittamer et al., 2011."Morphologic analyses revealed that the majority of cells exhibited the characteristics of monocytes/macrophages namely low nuclear to cytoplasm ratios and a high number of cytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 3B).

We thank you for pointing out the reference to Wittamer et al., 2011. In that study, we indeed provided the first morphological characterization of mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs) in various adult zebrafish organs using the cd45:DsRed line in combination with the mhc2dab:GFP reporter. The focus was primarily on MNPs across peripheral tissues. In the current study, our aim is broader: we investigate the full diversity of brain immune cells, using cd45 as a general marker for leukocytes. As part of this comprehensive characterization, we applied MGG staining, a widely accepted cytological technique, to gain morphological insight into the sorted CD45:DsRed+ population. This method remains a valuable and rapid approach to visually assess cell type heterogeneity, especially when evaluating samples where multiple immune cell lineages may be present.

While there is some overlap with the methodology used in Wittamer et al., the context, scope, and tissue examined differ substantially. Thus, the inclusion of MGG staining in this study serves to complement our broader transcriptomic analyses by providing supporting morphological evidence specific to brain-resident immune cells.

We have now clarified this distinction in the revised manuscript to better differentiate the current work from our previous findings (see line 85).

Figure 5 data should be quantified.

Please refer to our response in the major comments section, where we address this question in detail.

Figure 7- Figure Supplement 1. J, K has no CD45:DsRed positive cells in baf3 mutants, which is counterintuitive because CD45:DsRed should capture all hematopoietic cells and is not specific to dendritic cells.

It is correct that cd45 is a general leukocyte marker, labeling all immune cells, including dendritic cells. In this Figure, we used the Tg(cd45:DsRed) transgenic line to visualize the phenotype because it offers an alternative to IHC, with the advantage of strong endogenous fluorescence and easier screening of vibratome sections. However, this technique has limitations: due to fixation, only cells with high fluorescence (e.g. cd45<sup>high</sup>dendritic cells) are captured, while those with medium/low expression (e.g. cd45<sup>low</sup> microglia) are often not visible. This explains why fewer cells are observed in both wild-type and ba43 mutant brains (Figure 5 KN, Figure 7 – supplement 1 JK). While this approach is quicker and allows for thicker sections, IHC remains the preferred method for the rest of the analyses, including the use of additional markers to identify all relevant cell populations.

Thank you for bringing this point of confusion to our attention. To improve clarity, we have amended the text in the relevant sections (see lines 704-706, and legend of Figure 7 Supplement 1)

Minor issues:

The terms in the title, "A single-cell transcriptomic atlas..." are used. What is meant by "atlas"? A searchable database or website is not provided.

Please refer to our response in the major comments section, where we explain that we have made our dataset accessible through a searchable web interface (https://scrna-analysiszebrafish.shinyapps.io/scatlas/) which is now referenced in the Data Availability Statement.

This reviewer considers that it is offensive to use terminology such as "poorly characterized" in reference to others' work.

Thank you for pointing this out. We understand the concern and have revised the wording to ensure it remains respectful and neutral when referring to previous work. The changes are reflected in lines 20 and 49.

The introduction of this manuscript should consider restructuring and editing. Example: Lines 51-57 introduce the importance of immune cells in zebrafish regeneration studies. However, this study does not investigate such processes. Additionally, the authors focus on the concept of immune heterogeneity in the brain throughout the text however, these studies have been conducted previously by others (Silva et al., 2021) at single-cell level.

The novelty of this manuscript is the identification of "dendritic-like cells" and yet the introduction and text are limited to 68-71 lines. The introduction would benefit by introducing this cell type "dendritic-like cells" and differences between vertebrates.

Thank you for these valuable comments. In response, we have revised the introduction to better align with the focus of the study (see edited text in page 2). We now emphasize that, while macrophages have been extensively studied in zebrafish, dendritic cells remain much less well characterized in this model. Also, while we acknowledge that Silva et al. addressed aspects of immune heterogeneity in the zebrafish brain, their study primarily focused on mononuclear phagocytes. In contrast, our work provides a broader and more detailed characterization of the brain immune landscape, integrating transcriptomic data with multiple fluorescent reporter lines and hematopoietic mutants to strengthen cell identity assignments. Importantly, we note that Silva et al. classified DC-like cells within the microglial compartment, whereas our findings support that these cells represent a distinct population. While our data challenge this specific aspect of their conclusions, we believe both studies offer complementary insights that collectively advance our understanding of zebrafish brain immunity.

Though Figure 6 is a great conformation of scRNA sequencing, it seems redundant and should be supplemental data.

We respectfully disagree with the reviewer’s suggestion. We believe that presenting the data in Figure 6 as the main figure enhances its visibility and impact, particularly highlighting the distinction between microglia and DC-like cells, an aspect we consider highly valuable information for the zebrafish research community. This is especially important given that our conclusions challenge two previous independent reports, further underscoring the relevance of these findings to the field.

/hyperpost/🌐/🎭/gyuri/📓/2025/10/3/index.html

daily notes - third week of October 2025

daily notes - third week of October 2025

x

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors show that in E. coli the initiator protein DnaA oscillates post-translationally: its activity rises and peaks exactly when DNA replication begins, even if dnaA transcription is held constant. To explain this, they propose an "extrusion" mechanism in which nucleoid-associated proteins such as H-NS, whose amount grows with cell volume, dislodge DnaA from chromosomal binding sites; modelling and H-NS perturbations reproduce the observed drop in initiation mass and extra initiations seen after dnaA shut-down. Together, the data and model link biomass growth to replication timing through chromosome-driven, post-translational control of DnaA, filling gaps left by classic titration and ATP/ADP-switch models.

Strengths:

(1) Introduces an "extrusion" model that adds a new post-translational layer to replication control and explains data unexplained by classic titration or ATP/ADP-switch frameworks.

(2) A major asset of the study is that it bridges the longstanding gap between DnaA oscillations and DNA-replication initiation, providing direct single-cell evidence that pulses of DnaA activity peak exactly at the moment of initiation across multiple growth conditions and genetic perturbations.

(3) A tunable dnaA strain and targeted H-NS manipulations shift initiation mass exactly as the model predicts, giving model-driven validation across growth conditions.

(4) A purpose-built Psyn66 reporter combined with mRNA-FISH captures DnaA-activity pulses with cell-cycle resolution, providing direct, compelling data.

Weaknesses:

(1) What happens to the (C+D) period and initiation time as the dnaA mRNA level changes? This is not discussed in the text or figure and should be addressed.

(2) It is unclear what is meant by "relative dnaA mRNA level." Relative to what? Wild-type expression? Maximum expression? This should be explicitly defined.

(3) It would be helpful to provide some intuition for why an increase in dnaA mRNA level leads to a decrease in initiation mass per ori and an increase in oriC copy number.

(4) The titration and switch models do not explicitly include dnaA mRNA in the dynamics of DnaA protein. Yet, in Figure 2G, initiation mass is shown to decrease linearly with dnaA mRNA level in these models. How was dnaA mRNA level represented or approximated in these simulations?

(5) Is Schaechter's law (i.e., exponential scaling of average cell size with growth rate) still valid under the different dnaA mRNA expression conditions tested?

(6) The manuscript should explain more explicitly how the extrusion model implements post-translational control of DnaA and, in particular, how this yields the nonlinear drop in relative initiation mass versus dnaA mRNA seen in Fig. 6E. Please provide the governing equation that links total DnaA, the volume-dependent "extruder" pool, and the threshold of free DnaA at initiation, and show-briefly but quantitatively-how this equation produces the observed concave curve.

(7) Does this Extrusion model give well well-known adder per origin, i.e., initiation to initiation is an adder.

(8) DnaA protein or activity is never measured; mRNA is treated as a linear proxy. Yet the authors' own narrative stresses post-translational (not transcriptional) control of DnaA. Without parallel immunoblots or activity readouts, it is impossible to know whether a six-fold mRNA increase truly yields a proportional rise in active DnaA.

(9) Figure 2 infers both initiation mass and oriC copy number from bulk measurements (OD₆₀₀ per cell and rifampicin-cephalexin run-out) instead of measuring them directly in single cells. Any DnaA-dependent changes in cell size, shape, or antibiotic permeability could skew these bulk proxies, so the plotted relationships may not accurately reflect true initiation events.

Comments on revisions:

The authors have addressed all of my previous concerns, questions, and suggestions sufficiently.

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The study by Li and coworkers addresses the important and fundamental question of replication initiation in Escherichia coli, which remains open, despite many classic and recent works. It leverages single-cell mRNA-FISH experiments in strains with titratable DnaA and novel DnaA activity reporters to monitor DNA activity peaks versus size. The authors find oscillations in DnaA activity and show that their peaks correlate well with the estimated population-average replication initiation volume across conditions and imposed dnaA transcription levels. The study also proposes a novel extrusion model where DNA-binding proteins regulate free DnaA availability in response to biomass-DNA imbalance. Experimental perturbations of H-NS support the model validity, addressing key gaps in current replication control frameworks.

Strengths:

I find the study interesting and well conducted, and I think its main strong points are:

(1) the novel reporters obtained with systematic synthetic biology methods, and combined with a titratable dnaA strain.

(2) the interesting perturbations (titration, production arrest, and H-NS).

(3) the use of single-cell mRNA FISH to monitor transcripts directly.

The proposed extrusion model is also interesting, though not fully validated, and I think it will contribute positively to the future debate.

We thank the reviewer for acknowledging the strengths of our study.

Weaknesses and Limitations:

(1) A relevant limitation in novelty is that DnaA activity and concentration oscillations have been reported by the cited Iuliani and coworkers previously by dynamic microscopy, and to a smaller extent by the other cited study by Pountain and coworkers using mRNA FISH.

(2) An important limitation is that the study is not dynamic. While monitoring mRNA is interesting and relevant, the current study is based on concentrations and not time variations (or nascent mRNA). Conversely, the study by Iuliani and coworkers, while having the drawback of monitoring proteins, can directly assess production rates. It would be interesting for future studies or revisions to monitor the strains and reporters dynamically, as well as using (as a control) the technique of this study on the chromosomal reporters used by Iuliani et al.

We acknowledge the value of dynamic measurements and clarify our methodological rationale.

While luliani et al. provided valuable temporal resolution through protein dynamics, our mRNA FISH approach achieves direct decoupling of transcriptional vs. post-translational regulation (Fig 4F-H), and condition flexibility across 7 growth rates (30-66 min doubling times). This trade-off sacrifices temporal resolution for enhanced population-scale resolution and perturbation flexibility. To directly address temporal coupling, future work will implement dual-color live imaging of DnaA activity concurrent with replication initiation events.

(3) Regarding the mathematical models, a lot of details are missing regarding the definitions and the use of such models, which are only presented briefly in the Methods section. The reader is not given any tools to understand the predictions of different models, and no analytical estimates are used. The falsification procedures are not clear. More transparency and depth in the analysis are needed, unless the models are just used as a heuristic tool for qualitative arguments (but this would weaken the claims). The Berger model, for example, has many parameters and many regimes and behaviors. When models are compared to data (e.g., in Figure 2G), it is not clear which parameters were used, how they were fixed, and whether and how the model prediction depends on parameters.

We agree that model transparency is essential for quantitative validation. To address this, all model parameters (DnaA synthesis rate, activation/deactivation rates etc.) are explicitly tabulated in Supplementary Information Table S6. For the titration (Hansen et al. 1991) and extrusion models, we derive analytical expressions for initiation mass (IM) sensitivity to DnaA expression in Supplementary Note 1. For Figure 2G/S6, we used published parameters (Berger & Wolde 2022 SI Table 2) with experiment growth conditions (μ = 1.54 h<sup>-1</sup>).

The extrusion model's validation relies primarily on its ability to resolve paradoxical initiation events under dnaA shutdown (Fig 6C), a test where other models fail categorically. While the Berger titration-switch hybrid can fit steady-state IM trends (Fig S6A), it cannot reproduce post-shutdown dynamics without ad hoc modifications (Fig S6B). We acknowledge that comprehensive analysis of all model regimes exceeds this study's scope but provide full simulation code for independent verification: https://github.com/BaiYangBqdq/dynamics_of_biomass_DNA_coordination

(4) Importantly, the main statement about tight correlations of peak volumes and average estimated initiation volume does not establish coincidence, and some of the claims by the authors are unclear in these respects (e.g., when they say "we resolve a 1:1 coupling between DnaA activity thresholds and replication initiation", the statement could be correct but is ambiguous). Crucially, the data rely on average initiation volumes (on which there seems to be an eternally open debate, also involving the authors), and the estimate procedure relies on assumptions that could lead to biases and uncertainties added to the population variability (in any case, error bars are not provided).

We acknowledge the limitations of population-level inference and have refined our claims: "Replication initiation volume scales proportionally with peak DnaA activity volume with a slope of 1.0 (R<sub>2</sub>=0.98, Fig 7G), indicating predictive correspondence rather than absolute coincidence. While population-level 𝑉<sub>𝑖</sub> estimation cannot resolve single-cell stochasticity, the consistent 𝑉*: 𝑉<sub>𝑖</sub> relationship across 20 conditions suggest DnaA activity thresholds predict initiation timing within physiological error margins”. Future work will implement simultaneously DnaA activity and replication forks by using microfluidic single-cell tracking.

(5) The delays observed by the authors (in both directions) between the peaks of DnaAactivity conditional averages with respect to volume and the average estimated initiation volumes are not incompatible with those observed dynamically by Iuliani and coworkers. The direct experiment to prove the authors' point would be to use a direct proxy of replication initiation, such as SeqA or DnaN, and monitor initiations and quantify DnaA activity peaks jointly, with dynamic measurements.

We acknowledge the observed temporal deviations between DnaA activity peaks (𝑉*) and population-derived volumes at initiation ( 𝑉<sub>𝑖</sub>) in certain conditions, in line with the findings of Iuliani et al. This might be mechanistically consistent with the time required for orisome assembly or oriC sequestration. They do not contradict our core finding that initiation occurs at a defined DnaA activity threshold (slope=1.0, R<sub>2</sub>=0.98 in 𝑉*: 𝑉<sub>𝑖</sub> correlation).

(6) While not being an expert, I had some doubt that the fact that the reporters are on plasmid (despite a normalization control that seems very sensible) might affect the measurements. Also, I did not understand how the authors validated the assumptions that the reporters are sensitive to DnaA-ATP specifically. It seems this assumption is validated by previous studies only.

We employed a plasmid-based reporter system to circumvent the significant confounding effects of chromosomal position on promoter activity, as extensively documented by Pountain et al., where local genomic context (e.g., nucleoid occlusion, supercoiling gradients, and neighboring operons) introduces uncontrolled variability. By housing the P<sub>syn66</sub> test promoter and P<sub>con</sub> normalization control in identical low-copy pSC101 vectors (<8 copies/ cell, Peterson & Phillips, Plasmid 2008), we ensured they experience equivalent physical and biochemical environments. This ratiometric design, where DnaA activity is calculated, actively corrects for global fluctuations in RNA polymerase availability, nucleotide pools, and plasmid copy number. Critically, P<sub>syn66</sub>’s architecture emulates natural DnaA-responsive elements: its strong DnaAboxes report free DnaA concentration, while its weak box is preferentially bound by DnaA-ATP (Speck et al., EMBO journal 1999), mirroring the nucleotide-state sensitivity of oriC and the native dnaA promoter. This system was indispensable for our central finding, as it uniquely enabled the decoupling of DnaA activity oscillations from transcriptional feedback (Fig. 4F-H), an experiment fundamentally impossible with chromosomally integrated reporters due to autoregulatory interference.

Overall Appraisal:

In summary, this appears as a very interesting study, providing valuable data and a novel hypothesis, the extrusion model, open to future explorations. However, given several limitations, some of the claims appear overstated. Finally, the text contains some selfevaluations, such as "our findings redefine the paradigm for replication control", etc., that appear exaggerated.

We thank the reviewer for highlighting the need for precise language in framing our conclusions. We have implemented the following substantive revisions throughout the manuscript to ensure claims align strictly with empirical evidence:

(1) Changed "redefine the paradigm for replication control" into "advance the paradigm for replication control" (Introduction)

(2) Changed "redefine bacterial cell cycle control" into "refine bacterial cell cycle control as a dynamic interplay..." (Discussion)

(3) Removed the term "spatial" from the Discussion's description of DnaA-chromosome interactions (Discussion, first paragraph).

(4) Changed "provides a blueprint" into "provides a valuable tool for dissecting spatial regulation..." (Discussion, final paragraph)

(5) Scrutinized all superlatives (e.g., "critical feat" into "important capability"; "fundamental principle of cellular organization" into "potential organizational strategy")

(6) Replaced the instances of "robust" with evidence-backed descriptors (e.g., "sensitive," "consistent")

(7) We agree that the extrusion model requires further validation and have emphasized this in Discussion: "While H-NS perturbation supports extrusion mechanism, future work should identify the full extruder interactome and elucidate how metabolic signals modulate their activity" (final paragraph)

This calibrated language more accurately represents our study as a conceptual advance with testable mechanisms, not a complete paradigm shift.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors show that in E. coli, the initiator protein DnaA oscillates post-translationally: its activity rises and peaks exactly when DNA replication begins, even if dnaA transcription is held constant. To explain this, they propose an "extrusion" mechanism in which nucleoidassociated proteins such as H-NS, whose amount grows with cell volume, dislodge DnaA from chromosomal binding sites; modelling and H-NS perturbations reproduce the observed drop in initiation mass and extra initiations seen after dnaA shut-down. Together, the data and model link biomass growth to replication timing through chromosome-driven, posttranslational control of DnaA, filling gaps left by classic titration and ATP/ADP-switch models.

Strengths:

(1) Introduces an "extrusion" model that adds a new post-translational layer to replication control and explains data unexplained by classic titration or ATP/ADP-switch frameworks.

(2) A major asset of the study is that it bridges the longstanding gap between DnaA oscillations and DNA-replication initiation, providing direct single-cell evidence that pulses of DnaA activity peak exactly at the moment of initiation across multiple growth conditions and genetic perturbations.

(3) A tunable dnaA strain and targeted H-NS manipulations shift initiation mass exactly as the model predicts, giving model-driven validation across growth conditions.

(4) A purpose-built Psyn66 reporter combined with mRNA-FISH captures DnaA-activity pulses with cell-cycle resolution, providing direct, compelling data.

We thank the reviewer for acknowledging the strengths of our study.

Weaknesses:

(1) What happens to the (C+D) period and initiation time as the dnaA mRNA level changes? This is not discussed in the text or figure and should be addressed.

We thank the reviewer for this important observation. Our data demonstrate that increased dnaA mRNA levels induce two compensatory changes in cell cycle progression:

(1) Earlier replication initiation, manifested as a reduced initiation mass: the initiation mass decreased from 5.6 to 2.6 (OD<sub>600</sub>·ml per 10<sup>10</sup> cells) as the relative dnaA mRNA level increased from 0.2 to 7.2 (normalized to the wild-type level) (Fig. 2F, red).

(2) Prolonged C+D period: Increased by approximately 60% (from 1.05 to 1.66 hours, Fig. 2F blue).

The complete quantitative relationship is now explicitly described in the Results section: “Concurrently, the initiation mass was reduced by 50%, and the period from initiation to division (C+D) was increased by ~60% (Fig. 2F)”

(2) It is unclear what is meant by "relative dnaA mRNA level." Relative to what? Wild-type expression? Maximum expression? This should be explicitly defined.

The relative dnaA mRNA level was obtained by normalizing to that in wild-type MG1655 cells grown in the same medium. To clarify this point, we have now marked the wild-type level in Fig. 1B, and a clear description of this has also been included in the figure caption.

(3) It would be helpful to provide some intuition for why an increase in dnaA mRNA level leads to a decrease in initiation mass per ori and an increase in oriC copy number.

Thank you for your valuable suggestion. Increased dnaA mRNA accelerates DnaA accumulation, causing cells to reach the initiation threshold at a smaller cell size (reducing initiation mass, Fig. 2F red). This earlier initiation increases oriC copies per cell at populational level (Fig. 2E). This mechanistic interpretation now appears in the Results: “As the DnaA expression level increases, DnaA activity reaches the initiation threshold earlier. Given that cell mass remained nearly unchanged, this earlier initiation led to an increase in population-averaged cellular oriC numbers (Fig. 2E).”

(4) The titration and switch models do not explicitly include dnaA mRNA in the dynamics of DnaA protein. Yet, in Figure 2G, initiation mass is shown to decrease linearly with dnaA mRNA level in these models. How was dnaA mRNA level represented or approximated in these simulations?

All models presented in this article omit explicit modeling of dnaA mRNA dynamics for simplicity. However, at steady state, the relative level of dnaA mRNA can be approximated by the relative expression rate of DnaA protein, as both reflect the expression level of DnaA. This detail is now clarified in the caption of Figure 2G.

(5) Is Schaechter's law (i.e., exponential scaling of average cell size with growth rate) still valid under the different dnaA mRNA expression conditions tested?

Schaechter's law describes the exponential scaling of average cell size with growth rate in bacteria. In our prior work (Zheng et al., Nature Microbiology 2020), where we demonstrated that Schaechter's law fails in slow-growth regimes. However, in current study, growth rate remained constant across different dnaA expression levels (Fig. 2C), and cell mass showed no significant change (Fig. 2D). Since Schaechter's law specifically addresses how cell size scales with growth rate, it does not apply here, as growth rate was invariant in our perturbations, which selectively alter replication initiation dynamics, not growth rate or size scaling.

(6) The manuscript should explain more explicitly how the extrusion model implements posttranslational control of DnaA and, in particular, how this yields the nonlinear drop in relative initiation mass versus dnaA mRNA seen in Figure 6E. Please provide the governing equation that links total DnaA, the volume-dependent "extruder" pool, and the threshold of free DnaA at initiation, and show - briefly but quantitatively - how this equation produces the observed concave curve.

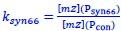

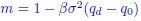

The governing equations linking initiation mass and DnaA expression level is now provided in Supplementary Note S1 for both the titration and the extrusion model. In general, the dependence of initiation mass (𝑉<sub>𝐼</sub>) on dnaA expression level (𝛼<sub>𝐴</sub>) dependency takes an inverse 1 proportionality form:  . In the extrusion model, the incorporated extruder protein is assumed to have similar synthesis dynamics as DnaA and can release DnaA from DnaA-box. After denoting the synthesis rate of the extruder as 𝛼<sub>𝐻</sub>, the combined effect of DnaA and the extruder on replication initiation can be briefly described as:

. In the extrusion model, the incorporated extruder protein is assumed to have similar synthesis dynamics as DnaA and can release DnaA from DnaA-box. After denoting the synthesis rate of the extruder as 𝛼<sub>𝐻</sub>, the combined effect of DnaA and the extruder on replication initiation can be briefly described as:  . Then the additive contribution of 𝛼<sub>𝐻</sub> dampens the sensitivity of initiation mass to changes in 𝛼<sub>𝐴</sub>, resulting in a significantly flattened curve. As a result, the predicted 𝑉<sub>𝐼</sub> − 𝛼<sub>𝐴</sub> relationship has a concave shape in the semi-log plots.

. Then the additive contribution of 𝛼<sub>𝐻</sub> dampens the sensitivity of initiation mass to changes in 𝛼<sub>𝐴</sub>, resulting in a significantly flattened curve. As a result, the predicted 𝑉<sub>𝐼</sub> − 𝛼<sub>𝐴</sub> relationship has a concave shape in the semi-log plots.

(7) Does this Extrusion model give well well-known adder per origin, i.e., initiation to initiation is an adder.

Yes, the extrusion model can provide the initiation-to-initiation adder phenomenon, this information was provided in fig. S3C.

(8) DnaA protein or activity is never measured; mRNA is treated as a linear proxy. Yet the authors' own narrative stresses post-translational (not transcriptional) control of DnaA. Without parallel immunoblots or activity readouts, it is impossible to know whether a sixfold mRNA increase truly yields a proportional rise in active DnaA.

We acknowledge the reviewer's valid concern regarding the indirect nature of our DnaA activity measurements. While mRNA levels alone cannot resolve active DnaA dynamics, our approach integrates functional replication outcomes with a validated synthetic reporter to infer activity. Crucially, elevated dnaA mRNA causes demonstrable biological effects: earlier replication initiation (Fig. 2F) and increased oriC copies (Fig. 2E), directly confirming enhanced functional DnaA activity at the oriC locus. The P<sub>syn66</sub> reporter, engineered with DnaA-boxes mirroring oriC's architecture, provides orthogonal validation, showing progressive repression to dnaA induction (Fig. 3C). Our operational metric  , bases on P<sub>syn66</sub> responds sensitively to DnaA-chromosome interactions within its characterized 8-fold dynamic range (Fig. 3C). Immunoblots would be inadequate here, as they cannot distinguish functionally critical pools: free versus chromosome-bound DnaA, or DnaA-ATP versus DnaAADP, precisely the post-translational states our study implicates in regulation. We therefore prioritize functional readouts (initiation timing) and the P<sub>syn66</sub> reporter, which probes the biologically active fraction relevant to replication control.

, bases on P<sub>syn66</sub> responds sensitively to DnaA-chromosome interactions within its characterized 8-fold dynamic range (Fig. 3C). Immunoblots would be inadequate here, as they cannot distinguish functionally critical pools: free versus chromosome-bound DnaA, or DnaA-ATP versus DnaAADP, precisely the post-translational states our study implicates in regulation. We therefore prioritize functional readouts (initiation timing) and the P<sub>syn66</sub> reporter, which probes the biologically active fraction relevant to replication control.

(9) Figure 2 infers both initiation mass and oriC copy number from bulk measurements (OD<sub>600</sub> per cell and rifampicin-cephalexin run-out) instead of measuring them directly in single cells. Any DnaA-dependent changes in cell size, shape, or antibiotic permeability could skew these bulk proxies, so the plotted relationships may not accurately reflect true initiation events.

We acknowledge the reviewer's valid methodological concern and clarify that while bulk measurements carry inherent limitations, our approach is grounded in established techniques with demonstrated reliability. Cell mass was inferred from OD600/cell, which correlates strongly with direct dry weight measurements and microscopic cell volumes across diverse growth conditions, as validated in our prior work (Zheng et al., Nature Microbiology 2020). Crucially, cell mass remained invariant across dnaA expression levels (Fig. 2D).

Regarding oriC quantification, the rifampicin-cephalexin run-out assay is a wildly applied for replication initiation studies. Our data shows expected 2<sup>n</sup> oriC distributions without abnormal ploidy (as shown below). While single-cell methods offer superior resolution, our bulk approach provides accurate population-level trends.

Author response image 1.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewing Editor Comments:

The reviewers felt that the mathematical modeling was not adequately explained in the paper, and that this affected the readability of the manuscript. The authors are encouraged to elaborate on this aspect of the paper (in addition to strengthening other claims, if possible, per the reviewers' comments).

We thank the editor and reviewers for their constructive feedback. We have comprehensively strengthened the mathematical modeling framework to enhance clarity and rigor.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

The only revision I would do is a recalibration of the claims and a major effort to clarify the modeling part (including a detailed SI appendix), without necessarily performing additional work.

To enhance mathematical modeling transparency, we have completed model description in the method section and a parameter table with literature-sourced values in Supplementary Information Table S6. Moreover, analytical derivations of initiation mass dependencies are performed and presented in the Supplementary Information Note S1.

Of course, there are extra experiments (mentioned in the public review) that would help support some of the big claims, but that can be considered a different project.

Thank you for your suggestion. This will be addressed in our future work.

Minor suggestion: please put signposts or plot jointly to compare the maxima/minima in Figures 4D, E, G, and H.

We added dashed lines in Figures 4D, and E, to synchronize visualization of DnaA activity peaks and transcriptional minima across panels, facilitating direct biological comparisons.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) Should define what DNA activity is.

We have explicitly defined DnaA activity in the Introduction as “the capacity to initiate replication…” and noted that it is “governed by free DnaA concentration, DnaA-ATP/-ADP ratio, and orisome assembly competence”.

(2) Word repetition - “...grown in in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium...”.

Corrected.

(3) Typographical error - “FISH ... was preformed" should be "performed”.

Corrected.

(4) The manuscript alternates between “ng ml<sup>-1</sup>” and “ng·ml<sup>-1</sup>”; choose one style and apply it uniformly.

Standardized the units to ng·ml<sup>-1</sup> throughout.

(5) Reference duplicates - Some citations appear twice in the bibliography (e.g., "Bintu et al., 2005a/b" and "Bintu et al., 2005b" listed again later).

The studies by Bintu et al. (2005a, 2005b) represent separate works: 2005a details applications, and 2005b develops models.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This paper introduces a new function within the Fam3Pro package that addresses the problem of breaking loops in family structures. When a loop is present, standard genotype peeling algorithms fail, as they cannot update genotypes correctly. The solution is to break these loops, but until now, this could not be done automatically and optimally.

The manuscript provides useful background on constructing graphs and trees from family data, detecting loops, and determining how to break them optimally for the case of no loops with multiple matings. For this situation, the algorithm switches between Prim's algorithm and a simple greedy approach and provides a solution. However, here, an optimal solution is not guaranteed.

The theoretical foundations-such as the representation of families as graphs or trees and the identification of loops-are clearly explained and well-illustrated with example pedigrees. The practical utility of the new function is demonstrated by applying it to a dataset containing families with loops.

This work has the potential for considerable impact, especially for medical researchers and individuals from families with loops. These families could previously not be analysed automatically and optimally. The new function changes that, enabling risk assessments and genetic calculations that were previously infeasible.

Strengths:

(1) The theoretical explanation of graphs, trees, and loop detection is clear and well-structured.

(2) The idea of switching between algorithms is original and appears effective.

(3) The function is well implemented, with minimal additional computational cost.

Weaknesses:

(1) In cases with multiple matings, the notion of a "close-to-optimal" solution is not clearly defined. It would be helpful to explain what this means-whether it refers to empirical performance, theoretical bounds, or something else.

(2) In the example pedigree discussed, multiple options exist for breaking loops, but it is unclear which is optimal.

(3) No example is provided where the optimal solution is demonstrably not reached.

(4) It is also unclear whether the software provides a warning when the solution might not be optimal.

Author response:

Response to Reviewer #1:

We plan to extend the discussion section to discuss the clinical implications of this new function. We will note the algorithm's applicability to broader genetic counseling contexts beyond cancer risk assessment.

Response to Reviewer #2:

We will clarify the four points raised:

(1) "Close-to-optimal" definition: We will explain that in multiple-mating cases, finding the global optimum is NP-hard (equivalent to the Weighted Feedback Vertex Set problem). We will clarify that our greedy algorithm provides practically efficient solutions suitable for clinical use, though without theoretical optimality guarantees.

(2) Example clarity: We will improve Figure 1's caption to explain the cost calculations and note that with equal weights, both shown solutions are equivalent.

(3) Non-optimal examples: We will describe scenarios where the greedy algorithm may not achieve the global optimum, particularly in multiple-mating cases with heterogeneous weights.

(4) Warning message: The current version not provide a warning when the solution might be non-optimal. This may be added in the future to the function.

We appreciate your feedback and suggestions to help improve the manuscript.

n the public mind Asian Americans are often synonymous with academic excellence, in part because their group scores on standardized tests and their college enrollment levels often exceed those of other groups, often including whites.

This tends to come with a lot of pressure that is put on the students because of stereotypes like the model minority. As mentioned in the text, stereotypes amongst Asians include. having high standardized scores, which can lead them to feeling forced to fit into this category. This leads to unhealthy habits which can affect their mental health nd well-being. Many are oblivious to the dangers that come with forcing stereotypes, especially when being forced to such high standards.

Some earlier studies during the legal segregation era indicated that manyAfrican Americans were encouraged, from a young age, to rigidly control theiranger and rage over discriminatory incidents affecting them.10 Historically, it wasvery dangerous for African Americans to unleash their anger about racist attacks.In earlier decades, black parents taught their children to remain even temperedin the face of extreme Jim Crow oppression, which silence demonstrably hadsevere effects on self-esteem and mental health—as it likely does in the case ofAfrican Americans and Asian Americans today

This reveals how systemic racism not only inflicts external harm but also demands internalized emotional discipline. The legacy of emotional containment reveals how racism operates through the regulation of affect shaping how marginalized communities are allowed to feel or express themselves. Seeing how both African Americans and Asian American communities have similar constraints shows how institutional racism continues to police emotional expression which tends to have negative effects on mental health and identity formation.

Althoughshe was rarely recognized for her significant involvement in important extra-curricular activities, people did associate her with academic excellence. Whileperforming well in school made her feel like an outsider, she worked hard foracademic success as a defensive mechanism

This really comes to show that academic success is no longer being a source of empowerment and joy but a shield against exclusion. Her excellence is only acknowledged narrowly and deeply confined to academics while her broader contributions are overlooked. This shows a systemic bias in regards to how merit is recognized. I think her relationship with school reveals how institutional cultures can distort the meaning of success, turning it to a coping mechanism for navigating environments.

Most school systems seem to allow much racist teasing. Respondents whoprotested to teachers were usually told not to take racial taunting seriously.Young Asian Americans are told to thicken their skin, while white and othernon-Asian children are often allowed to continue. The parents of tormentedstudents are frequently fearful about complaining of racial taunting and teasingand do not want to “cause trouble” or generate white retaliation. In this era ofschool multiculturalism, many administrators encourage teachers to celebratediversity in classrooms, and this superficial “be happy” multiculturalism maysometimes reduce their ability to see the impact of such racist treatment onstudents of color, as well as the underlying reality of institutionalized racism intheir educational institutions

This exposes how school systems tolerate racist bullying and exposes the tendency of institutions to mask harm with performative multiculturalism. Telling Asian American students to toughen up while excusing white peers behavior not only reflects bias but the systems refusal to confront racism. It is really upsetting to see that parents fear speaking out and feel that it is unnecessary due to the fear of being further discriminated against.

More Discrimination: The High School Asian Experience

Many Chinese students also face similar pressures within the exam-oriented education system: “excellence” becomes a moral label, with no room for failure or emotional expression. This is especially true when studying abroad. Chinese students are often defined as “quiet, strong in science, and lacking creativity”—a narrative that closely mirrors Ann's own experience.

As children attend child-care facilities and elemen-tary school, they are gradually introduced to racial socialization in peer groups. Young children’s racist behavior is often excused by adults on the grounds that children are naïve innocents and often slip and fall in the realm of social behavior, yet the assumption that children’s racist comments and actions are innocuous is incorrect. Based on extensive field research in a large child-care center, Debra Van Ausdale and Joe Feagin concluded that the “strongest evidence of white adults’ conceptual bias is seen in the assumption that children experience life events in some naïve or guileless way.”5 Children mimic adults’ racist views and behavior, but that does not mean they do not understand and know numerous elements of the dominant racial frame and use its stereotypes and interpretations to enhance their status among other children.

Children are not born racists; they learn racial hierarchies by imitating the behaviors of adults and peers. White children reproduce the social order of “white supremacy” through language and mockery, while Asian children are marginalized from a young age, subjected to ridicule about their appearance and food, thereby learning their subordinate place within the social racial structure. Schools are not neutral learning environments but spaces that reproduce social hierarchies. Through seemingly “playful” interactions, children learn who belongs to the ‘mainstream’ and who is the “other,” while teachers' silence effectively endorses this structure. Similar social stratification exists within China's educational environment—manifesting in stereotypes targeting non-local students, ethnic minorities, those with distinct accents, or students deemed “unsociable.” We frequently hear excuses like “He's just a child, he doesn't understand” to justify discriminatory remarks.

, far from a solipsistic politics ofconsciousness oblivious to material context, many sought to buildlives “not on stoned indifference but on active social engagementand community-oriented hard work” (p. 3) that would create newenvironments, public spaces (Silos, 2003), “right livelihoods,” andalternative social “games” in line with their values (notably bymoving “back-to-the-land” and setting up farms and communes

Rejecting of the American norm

如果你没中子宫彩票,那么选择并从事一份职业将是人生绕不过去的课题。今天的“职业”似乎成了万恶之源,因为“工作就是为了不工作”,“努力是为了不努力”。今天的年轻人,人生目标出奇的一致:财务自由。我希望本期节目能完成一个论证:财务自由是一个让你输在起跑线上的糟糕目标。以它为目标,很可能会导致你财务严重不自由。 通常理解是:从事一份职业,是把自己当成商品,通过出售自己的时间和精力来换取报酬。更抽象地说,“职业”是通过解决他人问题来解决自己问题的生存模式,这是商业分工导致的必然结果。问题A与问题B的汇率是不同的,一名患者的致命问题,对一名医生而言可能只是一个常规问题,之间巨大的知识差,让前者愿意倾家荡产换取。生死问题比清洁问题重要,医生待遇比环卫工人更好。

研究绝大多数人都绕不开的一个的重要话题——职业。那么我们应该如何才能认知职业的本质,让我们从本质、底层逻辑层面进行深刻理解。进而深刻的理解他、认知他、掌握它、运用它? 职业是一种生存模式,是一种解决自身问题的生存模式,目标是解决自身的生存问题的模式。但是这种模式必须要进行连接,要将自己的能力、目标与他人进行连接,才能形成并建立一种稳定的联系。 例如:医生是将自己的技能与患者之间的需求进行一种一对多的映射联系,企业家是将自己的综合能力与社会上更加广泛的人们需求建立联系,一个成功的企业家,自然它的服务受众也会约广泛,例如:库克、马斯克、马云。 结论:职业是一种将自己与他人建立联系并解决自身生存问题的生存模式。 职业的价值大小、能力的强弱,评价指标就是自己的职业范畴服务、联系的人员数量人员范畴的人员规模大小,联系强度的强弱。

关于赚钱的「观念」、「意愿」和「能力」是三回事,它们息息相关,但不能混为一谈。观念不同,会导致意愿的天差地别,意愿不同,则会使得养成的能力大相径庭。很多人有钱,就是因为足够贪婪,足够贪婪的同时又足够愚妄,以至于能完美自欺,彻底认同主流意识形态,没有一丝自我怀疑,冒进的风险偏好配合正常的智力,在特定历史阶段下就能赚到大钱,所谓“傻有钱”就是这么来的。我称之为“傻子钱”,不是说坑傻子赚到的钱,而是通过「未经反思的观念和意愿」赚到钱的这个人,在爱智的意义上就是个“傻子”。

观念、意愿和能力,他们三者之前到底有什么样的区别和联系?他们在赚钱这个核心的目标实现过程中分别扮演什么样的角色和作用? 那么在赚钱的这个目标过程中,是否有底层逻辑、原理是通行、通用的,有没有相对稳定的模型、规则是适用统配的?有没有具体的措施、案例可以印证? 从而让赚钱这件事情,看上去更加通透、触及本质。

Cognitive artefacts may be seen in terms of functioning in a similar fashion to the equivalent human cognitive process. This is the basis for seeing computer reasoning as a model of the human mind

Producers of these programs had to adjust their approach when introducing AI to society - instead of a cold robotic, non-existent relationship, they created a false impression of a real "entity" with reason/logic; when in reality it is a program with instructions and training.

In Gemini vs. ChatGPT exercise I asked the programs opinions on my topic and whether they thought the hypothesis was correct according to the findings (in their opinion), like it had thoughts of its own to see what both programs would think.

This introduces an essentially asymmetric relationship between human agent and thing rather than the broadly symmetric interaction implicit in the parity principle. In some respects, this might appear to be akin to the distinction between 'primary agency' and 'secondary agency' (for example, Gell 1998, 21) in which, unlike humans, things do not have agency in themselves but have agency given or ascribed to them. However, the increasing assignment of intelligence in digital devices that enables them to act independent of human agents could suggest that some digital cognitive artefacts possess primary agency as they autonomously act on others – both human and non-human/inanimate things. Arguably this agency is still in some senses secondary in that it is ultimately provided via the human programmer even if this is subsequently subsumed within a neural network generated by the thing itself, for example. This is not the place to develop the discussion of thing agency further (for example, see the debate between Lindstrøm (2015), Olsen and Witmore (2015), and Sørensen (2016)); however, the least controversial position to adopt here is to propose that for the most part the agency of digital cognitive artefacts employed by archaeologists complements rather than duplicates through extending and supporting archaeological cognition. They do this, for example, through providing the capability of seeing beneath the ground or characterising the chemical constituents of objects, neither of which are specifically human abilities. So there is considerable scope for considering the nature of the relationship between ourselves as archaeologists and our cognitive artefacts – how do we interact and in what ways is archaeological cognition extended or complemented by these artefacts?

While controversial, the addition of intelligence to digital cognitive artifacts making them operate independently from humans, remains a completely necessary step in advancement. There are some tasks which would simply require too much time, or are actually impossible for humans to complete if the process relied on their intelligence alone. The ability for an artifcat to work on its own allows for an incredible increase in effeciency, making things that were deemed impossible 20 years ago into a reality.

Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Note: This preprint has been reviewed by subject experts for Review Commons. Content has not been altered except for formatting.

Reply to the Reviewers

We thank the reviewers for their positive assessments overall and for many helpful suggestions for clarification to make the manuscript more accessible to a broader audience. We made minor text changes and added more labels to the figures to address these comments.

__Referee #1

__

Summary: In this study, the authors show a genetic interaction of the lipid receptors Lpr-1, Lpr-3 and Scav-2 in C. elegans. They show that Lpr-1 loss-of-function specifically affects aECM localization of Lpr-3 and attribute the lethality of Lpr-1 mutants to this phenotype. The authors performed a mutagenesis screen and identified a third lipid receptor, Scav-2, as a modulating factor: loss of scav-2 partially rescues the Lpr-1 phenotype. The authors created a variety of tools for this study, notably Crispr-Cas9-mediated knock-ins for endogenous tagging of the receptors.

Major comments:

while the authors provide a nice diagram showing the potential roles and interplay of lpr-1, lpr-3 and scav-2, it remains unclear what their respective cargo is. The nature of interaction between the proteins remains unclear from the data.

Response

As an optional (since time-consuming) experiment I would suggest trying more tissue-specific lipidomics.

Response

The lipidomics data should be presented in the figures, even if there were no significant changes. Importantly, show the lipid abundance at least of total lipids, better of individual classes, normalized to the material input (e.g. number of embryos, protein).

Response

Figure 1g: I do not understand what the lpr3:gfp signal is: the punctae in the overview image? and where are they in the zoom image showing anulli and alae? Also, how where the anulli and alae structures labeled? please provide more information

Response

One point that is not sufficiently adressed is that the authors deduce from the inability of the scav-2 gfp knock in to suppress lpr1 lethality that scav2 function is not impaired. This is quite indirect. Can the authors provide more convincing evidence that scav-2 ki has normal function?

Response

In general, the data is clearly presented and the statistical analyses look sound.

Response

__Minor comments: __

Please provide page and line numbers!

Response:

Avoid contractions like "don't" in both text and figure legends

Response:

Page 12: I do not understand the meaning of the sentence "This transgene also caused more modest lethality in a wild-type background"

Response:

Figure 7: what is meant with "Dodt"?

Response:

Reviewer #1 (Significance (Required)):

The study is experimentally sound and uses numerous novel tools, such as endogenously tagged lipid receptors. It is an interesting study for researchers in basic research studying lipid receptors and ECM biology. It provides insights on the genetic interaction of lipid receptors. My expertise is in lipid biochemistry, inter-organ lipid trafficking and imaging. I am not very familiar with C. elegans genetics.

__Referee #2 __ 1. The manuscript is very well written; the documentation is fine, but some more details are needed for better following the subject for readers not familiar with nematode anatomy.

For instance, while alae are somehow explained, annuli are not - structures that look abnormal in lpr1 and lpr1-scav2 mutants (Fig. 5B).

Response

Moreover, the authors show in Fig. 1 the punctae etc in the epidermis, whereas in Fig. 2 the show Lpr3 accumulation or not in the duct and the pore (lpr1). How do they localize in the cells of these structures at high magnification? It is also important to see the Lpr3 localisation in lpr1 mutants shown in Fig. 2A with the quality of the images shown in Fig. 1F. This applies also to Figs. 4 and 5.

Responses:

I would like to see punctae in lpr1-scav2 doubles.

Response:

Regarding the central mechanism, one possibility is - what the authors describe - that Lpr1 is needed for Lpr3 accumulation in ducts and tubes. Alternatively, Lpr1 is needed for duct and tube expansion, in lack of which Lpr3 is unable to reach its destination that is the lumina. Scav2, in this scenario, might be antagonist of tube and duct expansion, and thereby rescue the Lpr1 mutant phenotype independently. Admittedly, the non-accumulation of Lpr3 in scav2 mutants argues against a lpr1-independent function of scav2.

Responses:

In any case, to underline the aspect of Lpr1-Scav2 dosage relationship, the authors may also have a look at Lpr3 distribution in lpr1 heterozygous, and lpr1-scav2 double heterozygous worms. In this spirit, it would be interesting to see the semi-dominant effects of scav2 on Lpr3 localisation in lpr1 mutants by microscopy.

Response:

One word to the overexpression studies: it is surprising that the amounts of Scav2 delivered by the expression through the grl-2 promoter in the lpr1, scav2 background are almost matching those by the opposite effect of scav2 mutations on lpr1 dysfunction.

Response:

One issue concerns the localization of scav2-gfp "rarely" in vesicles: what are these vesicles?

Response

One comment to the Let653 transgenes/knock-ins: the localization of transgenic Let653-gfp may be normal in lpr1 mutants because there are wild-type copies in the background.

Response