- Apr 2022

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

as in much of his published work, Barthes doesn’t just performcritique; he works to unsettle the performance of critique throughperformance, especially via his creative engagement with thefragmental text – an engagement, as I have argued above, which isvery much shaped by his own card index use.

-

the index card serves as bothexample and facilitator of the concept of the lexia.

-

it ispossible to view Barthes’ concept of the lexia as an almost literaltranslation of his own use of index cards for recording various ‘unitsof reading’ and other ideas and associations.

-

All of the major books that were to follow – Sade /Fourier / Loyola (1997), The Pleasure of the Text (1975), RolandBarthes by Roland Barthes (1977), A Lover’s Discourse (1990), andCamera Lucida (1993) – are texts that are ‘plural’ and ‘broken’, andwhich are ‘constructed from non-totalizable fragments and fromexuberantly proliferating “details”’ (Bensmaïa, 1987: xxvii-xxxviii).In all of the above cases the fragment becomes the key unit ofcomposition, with each text structured around the arrangement ofmultiple (but non-totalisable) textual fragments.

Does the fact that Barthes uses a card index in his composition and organization influence the overall theme of his final works which could be described as "non-totalizable fragments"?

-

theprimary aim here is to explore how Barthes uses the notion of the‘non-totalisable’ fragment in his own work, and how this ties in witha discussion of his use of index cards.

a good summary of the overall paper?

-

According to Krapp, admissions like this, along with Barthes’inclusion of facsimiles of his cards in Roland Barthes by RolandBarthes, are all part of Barthes ‘outing’ his card catalogue as ‘co-author of his texts’ (Krapp, 2006: 363). The precise wording of thisformulation – designating the card index as ‘co-author’ – and theagency it ascribes to these index cards are significant in that theysuggest a usage that extends beyond mere memory aid to formsomething that is instrumental to the very organisation of Barthes’ideas and the published representations of these ideas.

-

As Calvet explains, this consisted of Barthes ‘writing out his cardsevery day, making notes on every possible subject, then classifyingand combining them in different ways until he found a structure or aset of themes’ (1994: 113) which he could proceed to work with.

-

What is evident from this discussion of Michelet and the earlierinterview excerpt is the way that Barthes used index cards both as anorganisational and as a problem-solving tool

Barthes used his card index as an organizational tool as well as a problem-solving tool.

-

As Calvetexplains, in thinking through the organisation of Michelet, Barthes‘tried out different combinations of cards, as in playing a game ofpatience, in order to work out a way of organising them and to findcorrespondences between them’ (113).

Louis-Jean Calvet explains that in writing Michelet, Barthes used his notes on index cards to try out various combinations of cards to both organize them as well as "to find correspondences between them."

-

Louis-Jean Calvet details the pivotal role played by indexcards in the organisation of Barthes’ Michelet.

-

published under the title‘An Almost Obsessive Relation to Writing Instruments’, which firstappeared in Le Monde in 1973

There is apparently an English translation by Linda Coverdale of this interview was published posthumously by University of California Press in The Grain of The Voice

There's also another edition The Grain of the Voice: Interviews 1962-1980 by Roland Barthes; Translated by Linda Coverdale; Northwestern University Press, 384 Pages, 5.50 x 8.50 in, 8 b-w Paperback, ISBN: 9780810126404; Published: December 2009, https://nupress.northwestern.edu/9780810126404/the-grain-of-the-voice/

Is there anything else worthwhile in this interview about note taking?

-

published under the title‘An Almost Obsessive Relation to Writing Instruments’, which firstappeared in Le Monde in 1973, Barthes describes the method thatguides his use of index cards:I’m content to read the text in question, in a ratherfetishistic way: writing down certain passages,moments, even words which have the power tomove me. As I go along, I use my cards to writedown quotations, or ideas which come to me, asthey do so, curiously, already in the rhythm of asentence, so that from that moment on, things arealready taking on an existence as writing. (1991:181)

In an interview with Le Monde in 1973, Barthes indicated that while his note taking practice was somewhat akin to that of a commonplace book where one might collect interesting passages, or quotations, he was also specifically writing down ideas which came to him, but doing so in "in the rhythm of a sentence, so that from that moment on, things are already taking on an existence as writing." This indicates that he's already preparing for future publications in which he might use those very ideas and putting them into a more finished form than most might think of when considering shorter fleeting notes used simply as a reminder. By having the work already done, he can easily put his own ideas directly into longer works.

Was there any evidence that his notes were crosslinked or indexed in a way so that he could more rapidly rearrange his ideas and pre-written thoughts to more easily copy them into longer articles or books?

-

By the early 1970s, Barthes’ long-standing use of index cards wasrevealed through reproduction of sample cards in Roland Barthes byRoland Barthes (see Barthes, 1977b: 75). These reproductions,Hollier (2005: 43) argues, have little to do with their content andare included primarily for reality-effect value, as evidence of anexpanding taste for historical documents

While the three index cards of Barthes that were reproduced in the 1977 edition of Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes may have been "primarily for reality-effect value as evidence of an expanding taste for historical documents" as argued by Hollier, it does indicate the value of the collection to Barthes himself as part of an autobiographical work.

I've noticed that one of the cards is very visibly about homosexuality in a time where public discussion of the term was still largely taboo. It would be interesting to have a full translation of the three cards to verify Hollier's claim, as at least this one does indicate the public consumption of the beginning of changing attitudes on previously taboo subject matter, even for a primarily English speaking audience which may not have been able to read or understand them, but would have at least been able to guess the topic.

At least some small subset of the general public might have grown up with an index-card-based note taking practice and guessed at what their value may have been though largely at that point index card note systems were generally on their way out.

-

Krapp argues that, despite its ‘respectablelineage’, the card index generally ‘figures only as an anonymous,furtive factor in text generation, acknowledged – all the way into thetwentieth century – merely as a memory crutch’ (361).2 A keyreason for this is due to the fact that the ‘enlightened scholar isexpected to produce innovative thought’ (361); knowledgeproduction, and any prostheses involved in it, ‘became and remaineda private matter’ (361).

'Memory crutch' implies a physical human failing that needs assistance rather than a phrase like aide-mémoire that doesn't draw that same attention.

-

Much of Barthes’ intellectual and pedagogical work was producedusing his cards, not just his published texts. For example, Barthes’Collège de France seminar on the topic of the Neutral, thepenultimate course he would take prior to his death, consisted offour bundles of about 800 cards on which was recorded everythingfrom ‘bibliographic indications, some summaries, notes, andprojects on abandoned figures’ (Clerc, 2005: xxi-xxii).

In addition to using his card index for producing his published works, Barthes also used his note taking system for teaching as well. His final course on the topic of the Neutral, which he taught as a seminar at Collège de France, was contained in four bundles consisting of 800 cards which contained everything from notes, summaries, figures, and bibliographic entries.

Given this and the easy portability of index cards, should we instead of recommending notebooks, laptops, or systems like Cornell notes, recommend students take notes directly on their note cards and revise them from there? The physicality of the medium may also have other benefits in terms of touch, smell, use of colors on them, etc. for memory and easy regular use. They could also be used physically for spaced repetition relatively quickly.

Teachers using their index cards of notes physically in class or in discussions has the benefit of modeling the sort of note taking behaviors we might ask of our students. Imagine a classroom that has access to a teacher's public notes (electronic perhaps) which could be searched and cross linked by the students in real-time. This would also allow students to go beyond the immediate topic at hand, but see how that topic may dovetail with the teachers' other research work and interests. This also gives greater meaning to introductory coursework to allow students to see how it underpins other related and advanced intellectual endeavors and invites the student into those spaces as well. This sort of practice could bring to bear the full weight of the literacy space which we center in Western culture, for compare this with the primarily oral interactions that most teachers have with students. It's only in a small subset of suggested or required readings that students can use for leveraging the knowledge of their teachers while all the remainder of the interactions focus on conversation with the instructor and questions that they might put to them. With access to a teacher's card index, they would have so much more as they might also query that separately without making demands of time and attention to their professors. Even if answers aren't immediately forthcoming from the file, then there might at least be bibliographic entries that could be useful.

I recently had the experience of asking a colleague for some basic references about the history and culture of the ancient Near East. Knowing that he had some significant expertise in the space, it would have been easier to query his proverbial card index for the lived experience and references than to bother him with the burden of doing work to pull them up.

What sorts of digital systems could help to center these practices? Hypothes.is quickly comes to mind, though many teachers and even students will prefer to keep their notes private and not public where they're searchable.

Another potential pathway here are systems like FedWiki or anagora.org which provide shared and interlinked note spaces. Have any educators attempted to use these for coursework? The closest I've seen recently are public groups using shared Roam Research or Obsidian-based collections for book clubs.

-

The filing cards or slipsthat Barthes inserted into his index-card system adhered to a ‘strictformat’: they had to be precisely one quarter the size of his usualsheet of writing paper. Barthes (1991: 180) records that this systemchanged when standards were readjusted as part of moves towardsEuropean unification. Within the collection there was considerable‘interior mobility’ (Hollier, 2005: 40), with cards constantlyreordered. There were also multiple layerings of text on each card,with original text frequently annotated and altered.

Barthes kept his system to a 'strict format' of cards which were one quarter the size of his usual sheet of writing paper, though he did adjust the size over time as paper sizes standardized within Europe. Hollier indicates that the collection had considerable 'interior mobility' and the cards were constantly reordered with use. Barthes also apparently frequently annotated and altered his notes on cards, so they were also changing with use over time.

Did he make his own cards or purchase them? The sizing of his paper with respect to his cards might indicate that he made his own as it would have been relatively easy to fold his own paper in half twice and cut it up.

Were his cards numbered or marked so as to be able to put them into some sort of standard order? There's a mention of 'interior mobility' and if this was the case were they just floating around internally or were they somehow indexed and tethered (linked) together?

The fact that they were regularly used, revise, and easily reordered means that they could definitely have been used to elicit creativity in the same manner as Raymond Llull's combinatorial art, though done externally rather than within one's own mind.

-

Barthes’ use of these cards goes back tohis first readin g of Michelet in 1943, which, as Hollier (2005: 40)notes, is more or less also the time of his very first articles. By 1945,Barthes had already amassed over 1,000 index cards on Michelet’swork alone, which he reportedly transported with him everywhere,from Romania to Egypt (Calvet, 1994: 113).

Note the idea here about how easily portable a 1,000 card index must have been or alternately how important it must have been that Barthes traveled with it.

-

In a remarkable essay on precursors to hypertext, Peter Krapp(2006) provides a useful overview of the development of the indexcard and its use by various thinkers, including Locke, Leibniz, Hegel,and Wittgenstein, as well as by those known to Barthes and part of asimilar intellectual milieu, including Michel Leiris, Georges Perec,and Claude Lévi-Strauss (Krapp, 2006: 360-362; Sieburth, 2005).1

Peter Krapp created a list of thinkers including Locke, Leibniz, Hegel, Wittgenstein, Barthes, Michel Leiris, Georges Perec, and Lévi-Strauss who used index cards in his essay Hypertext Avant La Lettre on the precursors of hypertext.

see also: Krapp, P. (2006) ‘Hypertext Avant La Lettre’, in W. H. K. Chun & T. Keenan (eds), New Media, Old Theory: A History and Theory Reader. New York: Routledge: 359-373.

Notice that Krapp was the translator of Paper Machines About Cards & Catalogs, 1548 – 1929 (MIT Press, 2011) by Marcus Krajewski. Which was writing about hypertext and index cards first? Or did they simply influence each other?

-

arthes’ use ofindex cards has been documented elsewhere (Krapp, 2006; Hollier,2005; Calvet, 1994)

Roland Barthes' use of index cards has been documented by the following:

Krapp, P. (2006) ‘Hypertext Avant La Lettre’, in W. H. K. Chun & T. Keenan (eds), New Media, Old Theory: A History and Theory Reader. New York: Routledge: 359-373.

Hollier, D. (2005) ‘Notes (on the Index Card)’, October 112 (Spring): 35-44.

Calvet, J.-L. (1994) Roland Barthes: A Biography. Trans. S. Wykes. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

-

Calvet, J.-L. (1994) Roland Barthes: A Biography. Trans. S. Wykes.Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Includes some research on the use Roland Barthes made of index cards for note taking to create his output.

-

Krapp, P. (2006) ‘Hypertext Avant La Lettre’, in W. H. K. Chun & T.Keenan (eds), New Media, Old Theory: A History and Theory Reader.New York: Routledge: 359-373.

-

Denis Hollier, in an essayon index card use by Barthes and Michel Leiris, argues that Leiris’use of index cards in writing his autobiography results in ‘asecondary, indirect autobiography, originating not from thesubject’s innermost self, but from the stack of index cards (theautobiographical shards) in the little box on the author’s desk’(Hollier, 2005: 39).

Wait, what?! Someone's written an essay on index card use by these two?!

-

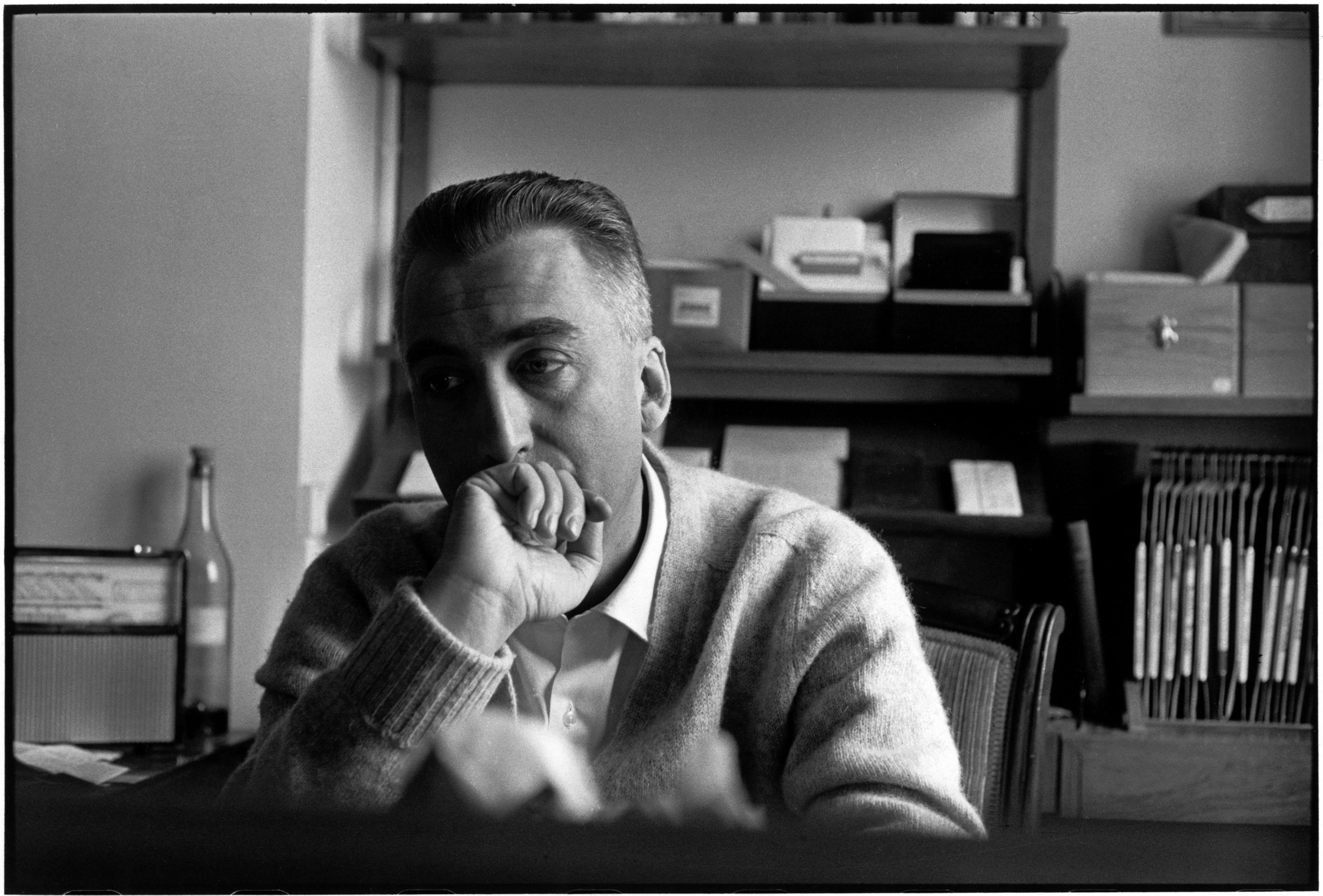

I am speaking here of what appear to be Barthes’ fichier boîte or indexcard boxes which are visible on the shelf above and behind his head.

First time I've run across the French term fichier boîte (literally 'file box') for index card boxes or files.

As someone looking into note taking practices and aware of the idea of the zettelkasten, the suspense is building for me. I'm hoping this paper will have the payoff I'm looking for: a description of Roland Barthes' note taking methods!

Tags

- innovation

- Roland Barthes

- note taking

- want to read

- hypertext

- anagora

- homosexuality

- anagora.org

- Georg Hegel

- Ludwig Wittgenstein

- lexias

- external scaffolding

- combinatorial creativity

- Obsidian

- Georges Perec

- Michel Leiris

- aide-mémoire

- card index as co-author

- thinking

- Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz

- book clubs

- fragments

- card index for teaching

- criticism

- portability

- index cards

- form versus function

- note taking methods

- Llullan combinatorial arts

- index card files

- paper machines

- Denis Hollier

- prostheses

- Louis-Jean Calvet

- Peter Krapp

- memory crutch

- Hypothes.is

- Marcus Krajewski

- autobiography

- card index for writing

- Le Monde

- zettelkasten

- fichier boîte

- open questions

- scaffolding

- commonplace books

- insight

- Claude Lévi-Strauss

- monkey see monkey do

- modelling behavior

- pedagogy

- 1973

- card index

- note linking

- fountain pens

- quotes

- external structures for thought

- zeitgeist

- memex

- Roam Research

- Jules Michelet

- social change

- historical documents

- 1977

- writing process

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Wp6q5hUdtA

Nice example of someone building their own paper-based zettelkasten an how they use it.

Seemingly missing here is any sort of indexing system which means one is more reliant on the threads from one card to the next. Also missing are any other examples of links to other cards beyond the one this particular card is placed behind.

Scott Scheper is using the word antinet, presumably to focus on non-digital versions of zettelkasten. Sounds more like a marketing word that essentially means paper zettelkasten or card index.

-

-

www.zylstra.org www.zylstra.org

-

2. What influence does annotating with an audience have on how you annotate? My annotations and notes generally are fragile things, tentative formulations, or shortened formulations that have meaning because of what they point to (in my network of notes and thoughts), not so much because of their wording. Likewise my notes and notions read differently than my blog posts. Because my blog posts have an audience, my notes/notions are half of the internal dialogue with myself. Were I to annotate in the knowledge that it would be public, I would write very differently, it would be more a performance, less probing forwards in my thoughts. I remember that publicly shared bookmarks with notes in Delicious already had that effect for me. Do you annotate differently in public view, self censoring or self editing?

To a great extent, Hypothes.is has such a small footprint of users (in comparison to massive platforms like Twitter, Facebook, etc.) that it's never been a performative platform for me. As a design choice they have specifically kept their social media functionalities very sparse, so one also doesn't generally encounter the toxic elements that are rampant in other locations. This helps immensely. I might likely change my tune if it were ever to hit larger scales or experienced the Eternal September effect.

Beyond this, I mostly endeavor to write things for later re-use. As a result I'm trying to write as clearly as possible in full sentences and explain things as best I can so that my future self doesn't need to do heavy work or lifting to recreate the context or do heavy editing. Writing notes in public and knowing that others might read these ideas does hold my feet to the fire in this respect. Half-formed thoughts are often shaky and unclear both to me and to others and really do no one any good. In personal experience they also tend not to be revisited and revised or revised as well as I would have done the first time around (in public or otherwise).

Occasionally I'll be in a rush reading something and not have time for more detailed notes in which case I'll do my best to get the broad gist knowing that later in the day or at least within the week, I'll revisit the notes in my own spaces and heavily elaborate on them. I've been endeavoring to stay away from this bad habit though as it's just kicking the can down the road and not getting the work done that I ultimately want to have. Usually when I'm being fast/lazy, my notes will revert to highlighting and tagging sections of material that are straightforward facts that I'll only be reframing into my own words at a later date for reuse. If it's an original though or comment or link to something important, I'll go all in and put in the actual work right now. Doing it later has generally been a recipe for disaster in my experience.

There have been a few instances where a half-formed thought does get seen and called out. Or it's a thought which I have significantly more personal context for and that is only reflected in the body of my other notes, but isn't apparent in the public version. Usually these provide some additional insight which I hadn't had that makes the overall enterprise more interesting. Here's a recent example, albeit on a private document, but which I think still has enough context to be reasonably clear: https://hypothes.is/a/vmmw4KPmEeyvf7NWphRiMw

There may also be infrequent articles online which are heavily annotated and which I'm excerpting ideas to be reused later. In these cases I may highlight and rewrite them in my own words for later use in a piece, but I'll make them private or put them in a private group as they don't add any value to the original article or potential conversation though they do add significant value to my collection as "literature notes" for immediate reuse somewhere in the future. On broadly unannotated documents, I'll leave these literature notes public as a means of modeling the practice for others, though without the suggestion of how they would be (re-)used for.

All this being said, I will very rarely annotate things privately or in a private group if they're of a very sensitive cultural nature or personal in manner. My current set up with Hypothesidian still allows me to import these notes into Obsidian with my API key. In practice these tend to be incredibly rare for me and may only occur a handful of times in a year.

Generally my intention is that ultimately all of my notes get published in something in a final form somewhere, so I'm really only frontloading the work into the notes now to make the writing/editing process easier later.

-

-

-

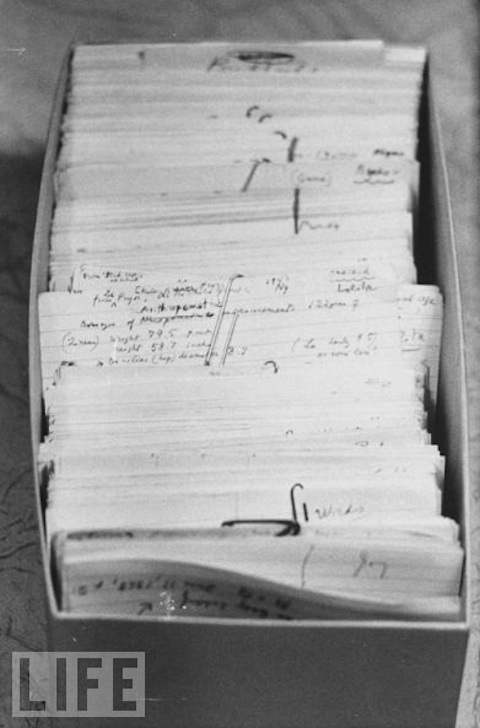

Nabokov arises early in the morning and works. He does hiswriting on filing cards, which are gradually copied, expanded, andrearranged until they become his novels.

-

Mr. Nabokov’s writing method is to compose his stories and novels on index cards,shuffling them as the work progresses since he does not write in consecutive order.Every card is rewritten many times. When the work is completed,the cards in final order, Nabokov dictates from them to his wifewho types it up in triplicate.

Vladimir Nabokov's general writing method consisted of composing his material on index cards so that he could shuffle them as he worked as he didn't write in consecutive order. He rewrote and edited cards many times and when the work was completed with the cards in their final order, Nabokov dictated them to his wife Vera who would type them up in triplicate.

-

-

www.loc.gov www.loc.gov

-

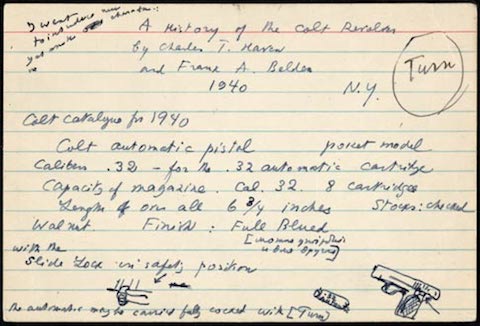

Nabokov’s working notecards for “Lolita.”

Nabokov used index cards for his research and writing. In one index card for research on Lolita, he creates a "weight-heigh-age table for girls of school age" to be able to specify Lolita's measurements. He also researched the Colt catalog of 1940 to get gun specifications to make those small points realistic in his writing.

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Colin Marshall</span> in The Notecards on Which Vladimir Nabokov Wrote Lolita: A Look Inside the Author's Creative Process | Open Culture (<time class='dt-published'>04/10/2022 12:18:34</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

www.openculture.com www.openculture.com

-

Reviewing The Original of Laura, Alexander Theroux describes the cards as a “portable strategy that allowed [Nabokov] to compose in the car while his wife drove the devoted lepidopterist on butterfly expeditions.”

While note cards have a certain portability about them for writing almost anywhere, aren't notebooks just as easily portable? In fact, with a notebook, one doesn't need to worry about spilling and unordering the entire enterprise.

There are, however, other benefits. By using small atomic pieces on note cards, one can be far more focused on the idea and words immediately at hand. It's also far easier in a creative and editorial process to move pieces around experimentally.

Similarly, when facing Hemmingway's White Bull, the size and space of an index card is fall smaller. This may have the effect that Twitter's short status updates have for writers who aren't faced with the seemingly insurmountable burden of writing a long blog post or essay in other software. They can write 280 characters and stop. Of if they feel motivated, they can continue on by adding to the prior parts of a growing thread. Sadly, Twitter doesn't allow either editing or rearrangements, so the endeavor and analogy are lost beyond here.

-

Having died in 1977, Nabokov never completed the book, and so all Penguin had to publish decades later came to, as the subtitle indicates, A Novel in Fragments. These “fragments” he wrote on 138 cards, and the book as published includes full-color reproductions that you can actually tear out and organize — and re-organize — for yourself, “complete with smudges, cross-outs, words scrawled out in Russian and French (he was trilingual) and annotated notes to himself about titles of chapters and key points he wants to make about his characters.”

Vladimir Nabokov died in 1977 leaving an unfinished manuscript in note card form for the novel The Original of Laura. Penguin later published the incomplete novel with in 2012 with the subtitle A Novel in Fragments. Unlike most manuscripts written or typewritten on larger paper, this one came in the form of 138 index cards. Penguin's published version recreated these cards in full-color reproductions including the smudges, scribbles, scrawlings, strikeouts, and annotations in English, French, and Russian. Perforated, one could tear the cards out of the book and reorganize in any way they saw fit or even potentially add their own cards to finish the novel that Nabokov couldn't.

Link to the idea behind Cain’s Jawbone by Edward Powys Mathers which had a different conceit, but a similar publishing form.

-

https://www.openculture.com/2014/02/the-notecards-on-which-vladimir-nabokov-wrote-lolita.html

Some basic information about Vladimir Nabokov's card file which he was using to write The Origin of Laura and a tangent on cards relating to Lolita.

Tags

- publishing

- creativity

- experimental fiction

- card index for writing

- zettelkasten

- The Original of Laura

- atomic notes

- Hemingway's White Bull

- tools for creativity

- combinatorial creativity

- Cain's Jawbone

- Lolita

- Vladimir Nabokov

- card index

- lepidopterists

- focus

- Penguin

- butterflies

- Edward Powys Mathers

- portability

- index card files

- writing

- index cards

- read

Annotators

URL

-

-

newrepublic.com newrepublic.com

-

An alternate view of Roland Barthes, likely taken in his 1963 session with Henri Cartier-Bresson. Index card boxes can be seen on the shelf behind him.

-

-

www.researchgate.net www.researchgate.net

-

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roland Barthes, 1963. © PAR79520 Henri CartierBresson/Magnum Photos.

A photo of Roland Barthes from 1963 featured in Picturing Barthes: The Photographic Construction of Authorship (Oxford University Press, 2020) DOI: 10.5871/bacad/9780197266670.003.0007

There appears to be in index card file behind him in the photo, which he may have used for note taking in the mode of a zettelkasten.

link to journal article notes on:

Wilken, Rowan. “The Card Index as Creativity Machine.” Culture Machine 11 (2010): 7–30. https://culturemachine.net/creative-media/

-

-

-

anadvocate for the index card in the early twentieth century, for example, called forthe use of index cards in imitation of “accountants of the modern school.”32

Zedelmaier argues that scholarly methods of informa- tion management inspired bureaucratic information management; see Zedelmaier (2004), 203.

Go digging around here for links to the history of index cards, zettelkasten, and business/accounting.

-

- Mar 2022

-

threadreaderapp.com threadreaderapp.com

- Feb 2022

-

-

In fact, my allegiance to Scrivener basically boils down to just three tricks that the software performs, but those tricks are so good that I’m more than willing to put up with all the rest of the tool’s complexity.Those three tricks are:Every Scrivener document is made up of little cards of text — called “scrivenings” in the lingo — that are presented in an outline view on the left hand side of the window. Select a card, and you see the text associated with that card in the main view.If you select more than one card in the outline, the combined text of those cards is presented in a single scrolling view in the main window. You can easily merge a series of cards into one longer card.The cards can be nested; you can create a card called, say, “biographical info”, and then drag six cards that contain quotes about given character’s biography into that card, effectively creating a new folder. That folder can in turn be nested inside another folder, and so on. If you select an entire folder, you see the combined text of all the cards as a single scrolling document.

Steven Johnson identifies the three features of Scrivener which provide him with the most value.

Notice the close similarity of these features to those of a traditional zettelkasten: cards of text which can be linked together and rearranged into lines of thought.

One difference is the focus on the creation of folders which creates definite hierarchies rather than networks of thought.

-

-

www.seattletimes.com www.seattletimes.com

-

‘Capitalizing on skepticism’: How the coronavirus has exposed us once again. (2022, February 16). The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/capitalizing-on-skepticism-how-the-coronavirus-has-exposed-us-once-again/

-

-

-

In preparing these instructions, Gaspard-Michel LeBlond, one of their authors, urges the use of uniform media for registering titles, suggesting that “ catalog materials are not diffi cult to assemble; it is suffi cient to use playing cards [. . .] Whether one writes lengthwise or across the backs of cards, one should pick one way and stick with it to preserve uniformity. ” 110 Presumably LeBlond was familiar with the work of Abb é Rozier fi fteen years earlier; it is unknown whether precisely cut cards had been used before Rozier. The activity of cutting up pages is often mentioned in prior descrip-tions.

In published instructions issued on May 8, 1791 in France, Gaspard-Michel LeBlond by way of standardization for library catalogs suggests using playing cards either vertically or horizontally but admonishing catalogers to pick one orientation and stick with it. He was likely familiar with the use of playing cards for this purpose by Abbé Rozier fifteen years earlier.

-

4. What follows is the compilation of the basic catalog; that is, all book titles are copied on a piece of paper (whose pagina aversa must remain blank) according to a specifi c order, so that together with the title of every book and the name of the author, the place, year, and format of the printing, the volume, and the place of the same in the library is marked.

Benedictine abbot Franz Stephan Rautenstrauch (1734 – 1785) in creating the Catalogo Topographico for the Vienna University Library created a nine point instruction set for cataloging, describing, and ordering books which included using paper slips.

Interesting to note that the admonishment to leave the backs of the slips (pagina aversa), in the 1780's seems to make its way into 20th century practice by Luhmann and others.

-

Rozier chances upon the labor-saving idea of producing catalogs according to Gessner ’ s procedures — that is, transferring titles onto one side of a piece of paper before copying them into tabular form. Yet he optimizes this process by dint of a small refi nement, with regard to the paper itself: instead of copying data onto specially cut octavo sheets, he uses uniformly and precisely cut paper whose ordinary purpose obeys the contingent pleasure of being shuffl ed, ordered, and exchanged: “ cartes à jouer. ” 35 In sticking strictly to the playing card sizes available in prerevolutionary France (either 83 × 43 mm or 70 × 43 mm), Rozier cast his bibliographical specifi cations into a standardized and therefore easily handled format.

Abbé François Rozier cleverly transferred book titles onto the blank side of French playing cards instead of cut octavo sheets as a means of indexing after being appointed in 1775 to index the holdings of the Académie des Sciences in Paris.

-

Therefore, they were frequently used as lottery tickets, marriage and death announcements, notepads, or busi-ness cards.

With blank backs, French playing cards in the late 1700s were often used as lottery tickets, marriage and death announcements, notepads, and business cards.

-

Playing cards offer numerous advantages: only after 1816 do their hitherto unmarked backs (fi gure 3.1) assumed a Tarot pattern.

Prior to 1816 in France playing cards (cartes à jouer) had unmarked backs and thereafter contained a Tarot pattern.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

cut out paper as Luhmann hadto.

On the back of his notes, you will find not only manuscript drafts, but also old bills or drawings by his children. [footnote]

While it's possible that Luhmann may have cut some of his own paper, by the time he was creating his notes the mass manufacture of index cards of various sizes was ubiquitous enough that he should never have had to cut his own. He certainly wasn't forced to manufacture them the way Carl Linnaeus had to.

-

- Jan 2022

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

Singh Chawla, D. (2022). Massive open index of scholarly papers launches. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00138-y

-

-

-

Here, the card index func-tions as a ‘thinking machine’,67 and becomes the best communication partner for learned men.68

From a computer science perspective, isn't the index card functioning like an external memory, albeit one with somewhat pre-arranged linked paths? It's the movement through the machine's various paths that is doing the "thinking". Or the user's (active) choices that create the paths creates the impression of thinking.

Perhaps it's the pre-arranged links where the thinking has already happened (based on "work" put into the system) and then traversing the paths gives the appearance of "new" thinking?

How does this relate to other systems which can be thought of as thinking from a complexity perspective? Bacteria perhaps? Groups of cells acting in concert? Groups of people acting in concert? Cells seeing out food using random walks? etc?

From this perspective, how can we break out the constituent parts of thought and thinking? Consciousness? With enough nodes and edges and choices of paths between them (or a "correct" subset of paths) could anything look like thinking or computing?

-

-

stevenson.ucsc.edu stevenson.ucsc.edu

-

ow about using a scratch pad slightly smaller than the page-size of the book -- so that the edges of the sheets won't protrude?

Interesting to note here that he suggests a scratch pad rather than index cards here given his own personal use of index cards.

-

- Dec 2021

-

luhmann.surge.sh luhmann.surge.sh

-

index card file

Given the use case that Niklas Luhmann had, the translation of zettelkasten into English is better read as "index card file" rather than the simpler and more direct translation "slip box".

While it's not often talked about in the recent contexts, there is a long history of using index cards for note taking in the United States and the idea of an index card file was once ubiquitous. There has been such a long span between this former ubiquity and our digital modernity that the idea of a zettelkasten seems like a wondrous new tool, never seen before. As a result, people in within social media, the personal knowledge management space, or the tools for thought space will happily use the phrase zettelkasten as if it is the hottest and newest thing on the planet.

-

-

aegir.org aegir.org

-

An absolutely beautiful design for short notes.

This is the sort of theme that will appeal to zettelkasten users who are building digital gardens. A bit of the old mixed in with the new.

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Pete Moor </span> in // pimoore.ca (<time class='dt-published'>12/24/2021 18:02:15</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

-

Commonplaces were no longer repositories of redundancy, but devices for storing knowledge expansion.

With the invention of the index card and atomic, easily moveable information that can be permuted and re-ordered, the idea of commonplacing doesn't simply highlight and repeat the older wise sayings (sententiae), but allows them to become repositories of new and expanding information. We don't just excerpt anymore, but mix the older thoughts with newer thoughts. This evolution creates a Cambrian explosion of ideas that helps to fuel the information overload from the 16th century onward.

-

Through an inner structure of recursive links and semantic pointers, a card index achieves a proper autonomy; it behaves as a ‘communication partner’ who can recommend unexpected associations among different ideas. I suggest that in this respect pre-adaptive advances took root in early modern Europe, and that this basic requisite for information pro-cessing machines was formulated largely by the keyword ‘order’.

aliases for "topical headings": headwords keywords tags categories

-

-

-

One more thing ought to be explained in advance: why the card index is indeed a paper machine. As we will see, card indexes not only possess all the basic logical elements of the universal discrete machine — they also fi t a strict understanding of theoretical kinematics . The possibility of rear-ranging its elements makes the card index a machine: if changing the position of a slip of paper and subsequently introducing it in another place means shifting other index cards, this process can be described as a chained mechanism. This “ starts moving when force is exerted on one of its movable parts, thus changing its position. What follows is mechanical work taking place under particular conditions. This is what we call a machine . ” 11 The force taking effect is the user ’ s hand. A book lacks this property of free motion, and owing to its rigid form it is not a paper machine.

The mechanical work of moving an index card from one position to another (and potentially changing or modifying links to it in the process) allows us to call card catalogues paper machines. This property is not shared by information stored in codices or scrolls and thus we do not call books paper machines.

-

Foucault proclaimed in a footnote: “ Appearance of the index card and development of the human sciences: another invention little celebrated by historians. ”

from Foucault 1975, p. 363, n. 49; see Foucault 1966, pp. XV and passim for discourse analysis.

Is he talking here about the invention of the index card about the same time as the rise of the scientific method? With index cards one can directly compare and contrast two different ideas as if weighing them on a balance to see which carries more weight. Then the better idea can win while the lesser is discarded to the "scrap heap"?

-

Here, I also briefl y digress and examine two coinciding addressing logics: In the same decade and in the same town, the origin of the card index cooccurs with the invention of the house number. This establishes the possibility of abstract representation of (and controlled access to) both texts and inhabitants.

Curiously, and possibly coincidently, the idea of the index card and the invention of the house number co-occur in the same decade and the same town. This creates the potential of abstracting the representation of information and people into numbers for easier access and linking.

-

What differs here from other data storage (as in the medium of the codex book) is a simple and obvious principle: information is available on separate, uniform, and mobile carriers and can be further arranged and processed according to strict systems of order.

The primary value of the card catalogue and index cards as tools for thought is that it is a self-contained, uniform and mobile carrier that can be arranged and processed based on strict systems of order. Books have many of these properties, but the information isn't as atomic or as easily re-ordered.

-

s Alan Turing proved only years later, these machines merely need (1) a (theoretically infi nite) partitioned paper tape, (2) a writing and reading head, and (3) an exact

procedure for the writing and reading head to move over the paper segments. This book seeks to map the three basic logical components of every computer onto the card catalog as a “ paper machine,” analyzing its data processing and interfaces that may justify the claim, “Card catalogs can do anything!”

Purpose of the book.

A card catalog of index cards used by a human meets all the basic criteria of a Turing machine, or abstract computer, as defined by Alan Turing.

-

“ Card catalogs can do anything ” — this is the slogan Fortschritt GmbH

What a great quote to start off a book like this!

-

- Nov 2021

-

-

Malamud’s General Index

-

-

docs.google.com docs.google.com

-

Now that we're digitizing the Zettelkasten we often find dated notes that say things like "note 60,7B3 is missing". This note replaces the original note at this position. We often find that the original note is maybe only 20, 30 notes away, put back in the wrong position. But Luhmann did not start looking, because where should he look? How far would he have to go to maybe find it again? So, instead he adds the "note is missing"-note. Should he bump into the original note by chance, then he could put it back in its original position. Or else, not.

Niklas Luhmann had a simple way of dealing with lost cards by creating empty replacements which could be swapped out if found later. It's not too dissimilar to doing inventory in a book store where mischievous customers pick up books, move them, or even hide them sections away. Going through occasionally or even regularly or systematically would eventually find lost/misfiled cards unless they were removed entirely from the system (similar to stolen books).

-

So the big secret then is, how did he know that this note here exists? How could he remember that this existing note was relevant to the new one he was writing? A mystery we haven't solved yet.

I'm surprised to see/hear this!

How did Niklas Luhmann cross link his notes? Apparently researchers don't quite know, but I'd suggest that in working with them diligently over time, he'd have a reasonable internal idea from memory in addition to working with his indices and his outline cards.

The cards in some sense form a physical path through which he regularly traverses, so he's making a physical memory palace (or songline) out of index cards.

-

-

-

const palette: { [key: string]: string } = {...

-

Object literals don't have index signatures. They are assignable to types with index signatures if they have compatible properties and are fresh (i.e. provably do not have properties we don't know about) but never have index signatures implicitly or explicitly.

-

Which... is confusing because Palette technically does have an index signature Palette is a mapped type, and mapped types don't have index signatures. The fact that both use [ ] is a syntactic coincidence.

-

Generate type with the index signature: interface RandomMappingWithIndexSignature { stringProp: string; numberProp: number; [propName: string]: string | number | undefined; }

-

we have no way to know that the line nameMap[3] = "bob"; isn't somewhere in your program

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

The other commenters are right about the potential solutions. However, it is actually considered a best practice to move the object with the index signature to a nested property.Said differently: No property in the object with the index signature should depart from how the index signature is typed.

-

Like others have noted, your function does not conform to index signature. [key: string]: string means "all fields are strings" and on the next line you declare a field with function in it.This can be solved by using union types:type IFoo = { [foo: string]: string } & { fooMethod(fooParam: string): void }

-

-

stackoverflow.com stackoverflow.com

-

So now the question is, why does Session, an interface, not get implicit index signatures while SessionType, an identically-structured typealias, *does*? Surely, you might again think, the compiler does not simply deny implicit index signatures tointerface` types? Surprisingly enough, this is exactly what happens. See microsoft/TypeScript#15300, specifically this comment: Just to fill people in, this behavior is currently by design. Because interfaces can be augmented by additional declarations but type aliases can't, it's "safer" (heavy quotes on that one) to infer an implicit index signature for type aliases than for interfaces. But we'll consider doing it for interfaces as well if that seems to make sense And there you go. You cannot use a Session in place of a WithAdditionalParams<Session> because it's possible that someone might merge properties that conflict with the index signature at some later date. Whether or not that is a compelling reason is up for rather vigorous debate, as you can see if you read through microsoft/TypeScript#15300.

-

why is Session not assignable to WithAdditionalParams<Session>? Well, the type WithAdditionalParams<Session> is a subtype of Session with includes a string index signature whose properties are of type unknown. (This is what Record<string, unknown> means.) Since Session does not have an index signature, the compiler does not consider WithAdditionalParams<Session> assignable to Session.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

on advocate for the index card in the early twentieth century called for animitation of “accountants of the modern schoolY”1

Paul Chavigny, Organisation du travail intellectuel: Recettes pratiques a` l’usage des e ́tudiants de toutes les faculte ́s et de tous les travailleurs (Paris, 1920)

Chavigny was an advocate for the index card in note taking in imitation of "accountants of the modern school". We know that the rise of the index card was hastened by the innovation of Melvil Dewey's company using index cards as part of their internal accounting system, which they actively exported to other companies as a product.

-

- Oct 2021

-

-

Else, H. (2021). Giant, free index to world’s research papers released online. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02895-8

-

- Sep 2021

-

stackingthebricks.com stackingthebricks.com

-

finiteeyes.net finiteeyes.net

-

Offloading can be far more complex, however, and doesn’t necessarily involve language. For example, “when we use our hands to move objects around, we offload the task of visualizing new configurations onto the world itself, where those configurations take tangible shape before our eyes” (243-244).

This is one of the key benefits over the use of index cards in moving toward a zettelkasten from the traditional commonplace book tradition. Rearranging one's ideas in a separate space.

Raymond Llull attempted to do this within his memory in the 12th century, but there are easier ways of doing this now.

-

-

ivankreilkamp.com ivankreilkamp.com

- Aug 2021

-

kimberlyhirsh.com kimberlyhirsh.com

-

https://kimberlyhirsh.com/2018/06/29/a-starttofinish-literature.html

Great overview of a literature review with some useful looking links to more specifics on note taking methods.

Most of the newer note taking tools like Roam Research, Obsidian, etc. were not available or out when she wrote this. I'm curious how these may have changed or modified her perspective versus some of the other catch-as-catch-can methods with pen/paper/index cards/digital apps?

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

I remember also seeing this as an indexing system for index cards in 2007. https://www.flickr.com/photos/hawkexpress/sets/72157594200490122/

It's not too dissimilar a pattern from the early 20th century edge-notched cards which were used to make sorting collections easier. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edge-notched_card Of course doing this for a notebook isn't going to work as easily.

-

-

www.connectedtext.com www.connectedtext.com

-

In writing my dissertation and working on my first book, I used an index card system, characterized by the "one fact, one card" maxim, made popular by Beatrice Webb. [4]

I've not come across Beatrice Webb before, but I'm curious to see what her system looks like based on this statement.

From the footnotes:

She observed in the appendix to her My Apprenticeship of 1926, called The Art of Note-Taking: "It is difficult to persuade the accomplished graduate of Oxford or Cambridge that an indispensable instrument in the technique of sociological enquiry - seeing that without it any of the methods of acquiring facts can seldom be used effectively - is the making of notes" Webb, Beatrice (1926) My Apprenticeship (London: Longmans, Green, and Co.), pp. 426-7.

-

-

wiki.c2.com wiki.c2.com

-

-

To me, the greatest benefit of IndexCards is that they force you to not write too much. This is a big help to those of us who are still squishing the bitter juice of BigDesignUpFront from our brains. The expense and rarity of vellum played a similar role in MedievalArchitecture.

-

This is one of the points made in TheMythOfThePaperlessOffice -- that workplaces often shift from more efficient paper-based technologies to less efficient electronic technologies (electronic technologies can be either more or less efficient, of course) because computers symbolize The Future, Progress, and a New Way Of Doing Things. An office on the move, that's what an office that uses cutting-edge technology is. Not an office that is stuck in the past. And the employees are left to cope with the less productive, but shinier, New Way. -- ApoorvaMuralidhara

New technologies don't always have the user interface to make them better than old methods.

-

-

web.archive.org web.archive.org

-

In 2003, Ross's family gave his journals, papers, and correspondence to the British Library, London. Then, in March 2004, on the last day of the W. Ross Ashby Centenary Conference, they announced the intention to make his journal available on the Internet. Four years later, this website fulfilled that promise, making this previously unpublished work available on-line.

The journal consists of 7,189 numbered pages in 25 volumes, and over 1,600 index cards. To make it easy to browse purposefully through so many images, extensive cross-linking has been added that is based on the keywords in Ross's original keyword index.

This definitely sounds like a commonplace book. Also an example of one which has been digitized.

-

-

edwardbetts.com edwardbetts.com

-

Now, whenever I have a thought worth capturing, I write it on an index card in either marker pen or biro (depending on the length of the thought), and place in the relevant box. I use index cards for books, blogs, conversations I overhear at the club, memories, etc. They’re in my coat pocket when I fetch the kids from school. I leave them handy in the locker at the swimming pool (where I do much of my best thinking). And I run with them. Sound weird? Well, I’m in good company. Ryan Holiday[116], Anne Lamott[117], Robert Greene[118], Oliver Burkeman[119], Ronald Reagan, Vladimir Nabokov[120] and Ludwig Wittgenstein[121] all use (d) the humble index card to catalogue and organise their thoughts. If you’re serious about embarking on this digital journey, buy a hundred-pack of 127 x 76mm ruled index cards for less than a pound, rescue a shoebox from the attic and stick a few marker-penned notecards on their end to act as dividers. Write a “My Digital Box” label on the top of the shoebox, and you’re off.

apparently a quote from Reset: How to Restart Your Life and Get F.U. Money by David Sawyer FCIPR.

Notes about users of index card based commonplace books.

-

-

groups.google.com groups.google.com

-

I am also interested in the work and method of Ross Ashby. His card index and notebooks have been put online by the British Commputer Society. I am fascinated by his law of requisite variety and how variety relates to complexity and its unfolding in general and in relation to design.

Sounds like Ross Ashby kept a commonplace book here.

Could be worth looking into: http://www.rossashby.info/ and digging further.

-

-

www.usatoday.com www.usatoday.com

-

http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/washington/2011-05-08-reagan-notes-book-brinkley_n.htm

An article indicating that President Ronald Reagan kept a commonplace book throughout his life. He maintained it on index cards, often with as many as 10 entries per card. The article doesn't seem to indicate that there was any particular organization, index, or taxonomy involved.

It's now housed at the Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, CA.

-

-

www.flickr.com www.flickr.com

-

I keep my index cards in chronological order : the newest card comes at front of the card box. All cards are clasified into four kinds and tagged according to the contents. The sequence is equivalent to my cultural genetic code. Although it may look chaotic at the beginning, it will become more regulated soon. Don't be afraid to sweep out your mind and capture them all. Make visible what is going on in your brain. Look for a pattern behind our life.

Example of a edge-based taxonomy system for index cards.

-

-

ryanholiday.net ryanholiday.net

-

Ronald Reagan also kept a similar system that apparently very few people knew about until he died. In his system, he used 3×5 notecards and kept them in a photo binder by theme. These note cards–which were mostly filled with quotes–have actually been turned into a book edited by the historian Douglas Brinkley. These were not only responsible for many of his speeches as president, but before office Reagan delivered hundreds of talks as part of his role at General Electric. There are about 50 years of practical wisdom in these cards. Far more than anything I’ve assembled–whatever you think of the guy. I highly recommend at least looking at it.

Ronald Reagan kept a commonplace in the form of index cards which he kept in a photo binder and categorized according to theme. Douglas Brinkley edited them into the book The Notes: Ronald Reagan's Private Collection of Stories and Wisdom.

-

- Jul 2021

-

hackaday.com hackaday.com

-

https://hackaday.com/2019/06/18/before-computers-notched-card-databases/

Originally suggested by Alan Levine. Some interesting specific examples here, but I've been aware of the concept for a while.

-

-

deepstash.com deepstash.com

-

https://deepstash.com/ appears to be a note taking tool geared toward zettelkasten and productivity. It's got an interesting card-based UI.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

boffosocko.com boffosocko.com

-

Your post says nothing at all to suggest Luhman didn’t “invent” “Zettelkasten” (no one says he was only one writing on scraps of paper), you list two names and no links

My post was more in reaction to the overly common suggestions and statements that Luhmann did invent it and the fact that he's almost always the only quoted user. The link was meant to give some additional context, not proof.

There are a number of direct predecessors including Hans Blumenberg and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. For quick/easy reference here try:

- https://jhiblog.org/2019/04/17/ruminant-machines-a-twentieth-century-episode-in-the-material-history-of-ideas/

- https://muse.jhu.edu/article/715738

If you want some serious innovation, why not try famous biologist Carl Linnaeus for the invention of the index card? See: http://humanities.exeter.ac.uk/history/research/centres/medicalhistory/past/writing/

(Though even in this space, I suspect that others were already doing similar things.)

-

-

www.hps.cam.ac.uk www.hps.cam.ac.uk

-

Researcher working on the idea of Carl Linnaeus and the invention of the index card.

-

-

www.synapsen.ch www.synapsen.ch

-

Synapsen, a digital card index by Markus Krajewski

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Goodreads</span> in Markus Krajewski (Author of Paper Machines) | Goodreads (<time class='dt-published'>07/04/2021 00:22:32</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

-

Forty years ago, Michel Foucault observed in a footnote that, curiously, historians had neglected the invention of the index card. The book was Discipline and Punish, which explores the relationship between knowledge and power. The index card was a turning point, Foucault believed, in the relationship between power and technology.

This piece definitely makes an interesting point about the use of index cards (a knowledge management tool) and power.

Things have only accelerated dramatically with the rise of computers and the creation of data lakes and the leverage of power over people by Facebook, Google, Amazon, et al.

-

In 1780, two years after Linnaeus’s death, Vienna’s Court Library introduced a card catalog, the first of its kind. Describing all the books on the library’s shelves in one ordered system, it relied on a simple, flexible tool: paper slips. Around the same time that the library catalog appeared, says Krajewski, Europeans adopted banknotes as a universal medium of exchange. He believes this wasn’t a historical coincidence. Banknotes, like bibliographical slips of paper and the books they referred to, were material, representational, and mobile. Perhaps Linnaeus took the same mental leap from “free-floating banknotes” to “little paper slips” (or vice versa).

I've read about the Vienna Court Library and their card catalogue. Perhaps worth reading Krajewski for more specifics to link these things together?

Worth exploring the idea of paper money as a source of inspiration here too.

-

according to Charmantier and Müller-Wille, playing cards were found under the floorboards of the Uppsala home Linnaeus shared with his wife Sara Lisa.

-

In 1791, France’s revolutionary government issued the world’s first national cataloging code, calling for playing cards to be used for bibliographical records.

Reference for this as well?

-

Linnaeus may have drawn inspiration from playing cards. Until the mid-19th century, the backs of playing cards were left blank by manufacturers, offering “a practical writing surface,” where scholars scribbled notes, says Blair. Playing cards “were frequently used as lottery tickets, marriage and death announcements, notepads, or business cards,” explains Markus Krajewski, the author of Paper Machines: About Cards and Catalogs.

There was a Krajewski reference I couldn't figure out in the German piece on Zettelkasten that I read earlier today. Perhaps this is what was meant?

These playing cards might also have been used as an idea of a waste book as well, and then someone decided to skip the commonplace book as an intermediary?

-

Linnaeus experimented with a few filing systems. In 1752, while cataloging Queen Ludovica Ulrica’s collection of butterflies with his disciple Daniel Solander, he prepared small, uniform sheets of paper for the first time. “That cataloging experience was possibly where the idea for using slips came from,” Charmantier explained to me. Solander took this method with him to England, where he cataloged the Sloane Collection of the British Museum and then Joseph Banks’s collections, using similar slips, Charmantier said. This became the cataloging system of a national collection.

Description of the spread of the index card idea.

-

More than 1,000 of them, measuring five by three inches, are housed at London’s Linnean Society. Each contains notes about plants and material culled from books and other publications. While flimsier than heavy stock and cut by hand, they’re virtually indistinguishable from modern index cards.

Information culled from other sources indicates they come from the commonplace book tradition. The index card-like nature becomes the interesting innovation here.

-

-

www.sciencedirect.com www.sciencedirect.com

-

The Swedish 18th-century naturalist Carolus (Carl) Linnaeus is habitually credited with laying the foundations of modern taxonomy through the invention of binominal nomenclature. However, another innovation of Linnaeus' has largely gone unnoticed. He seems to have been one of the first botanists to leave his herbarium unbound, keeping the sheets of dried plants separate and stacking them in a purpose built-cabinet. Understanding the significance of this seemingly mundane and simple invention opens a window onto the profound changes that natural history underwent in the 18th century.

-

-

www.sciencedirect.com www.sciencedirect.com

-

Dug up with respect to the idea of Carl Linnaeus inventing the idea of the index card.

-

-

www.sciencedaily.com www.sciencedaily.com

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Wikipedia</span> in Index card - Wikipedia (<time class='dt-published'>07/03/2021 21:36:58</time>)</cite></small>

Bookmarked at 10:41 PM

Read 11:09 PM

-

Towards the end of his career, in the mid-1760s, Linnaeus took this further, inventing a paper tool that has since become very common: index cards. While stored in some fixed, conventional order, often alphabetically, index cards could be retrieved and shuffled around at will to update and compare information at any time.

Invention of index card dated to the 1760's by Carl Linnaeus.

-

Linnaeus had to manage a conflict between the need to bring information into a fixed order for purposes of later retrieval, and the need to permanently integrate new information into that order, says Mueller-Wille. “His solution to this dilemma was to keep information on particular subjects on separate sheets, which could be complemented and reshuffled,” he says.

Carl Linnaeus created a method whereby he kept information on separate sheets of paper which could be reshuffled.

In a commonplace-centric culture, this would have been a fascinating innovation.

Did the cost of paper (velum) trigger part of the innovation to smaller pieces?

Did the de-linearization of data imposed by codices (and previously parchment) open up the way people wrote and thought? Being able to lay out and reorder pages made a more 3 dimensional world. Would have potentially made the world more network-like?

cross-reference McLuhan's idea about our tools shaping us.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

-

This system was invented by Carl Linnaeus,[1] around 1760.

How is it not so surprising that Carl Linnaeus, the creator of a huge taxonomic system, also came up with the idea for index cards in 1760.

How does this fit into the history of the commonplace book and information management? Relationship to the idea of a zettelkasten?

-

-

www.heise.de www.heise.de

-

Dafür spricht das Credo des Literaten Walter Benjamin: Und heute schon ist das Buch, wie die aktuelle wissenschaftliche Produktionsweise lehrt, eine veraltete Vermittlung zwischen zwei verschiedenen Kartotheksystemen. Denn alles Wesentliche findet sich im Zettelkasten des Forschers, der's verfaßte, und der Gelehrte, der darin studiert, assimiliert es seiner eigenen Kartothek.

The credo of the writer Walter Benjamin speaks for this:

And today, as the current scientific method of production teaches, the book is an outdated mediation between two different card index systems. Because everything essential is to be found in the slip box of the researcher who wrote it, and the scholar who studies it assimilates it in his own card index.

Here's an early instantiation of thoughts being put down into data which can be copied from one card to the next as a means of creation.

A similar idea was held in the commonplace book tradition, in general, but this feels much more specific in the lead up to the idea of the Memex.

-

- May 2021

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

Gallotti, R., Valle, F., Castaldo, N., Sacco, P., & De Domenico, M. (2020). Assessing the risks of ‘infodemics’ in response to COVID-19 epidemics. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(12), 1285–1293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00994-6

-

- Mar 2021

-

asia.nikkei.com asia.nikkei.com

-

meaning they do not matter much.

persepsi bahwa sitasi menunjukkan dampak atau arti dari suatu makalah, harus direvisi, karena di sisi lainnya, persepsi ini telah terbukti merusak kehidupan akademik. turunan dari persepsi ini adalah bahwa peneliti dengan jumlah sitasi (diwakili angka indeks H) yang banyak akan dianggap lebih bereputasi dibanding yang jumlah sitasinya sedikit.

-

-

-

Leatherby, Lauren, and Rich Harris. ‘States That Imposed Few Restrictions Now Have the Worst Outbreaks’. The New York Times, 18 November 2020, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/11/18/us/covid-state-restrictions.html.

-

- Feb 2021

-

developer.mozilla.org developer.mozilla.org

-

.box1 { grid-column-start: 1; grid-column-end: 4; grid-row-start: 1; grid-row-end: 3; } .box2 { grid-column-start: 1; grid-row-start: 2; grid-row-end: 4; }

-

- Jan 2021

-

developer.mozilla.org developer.mozilla.orgz-index1

- Dec 2020

-

www.fourtheconomy.com www.fourtheconomy.com

- Sep 2020

-

archive.theincline.com archive.theincline.com

-

www.irishtimes.com www.irishtimes.com

-

Taylor, Charlie. ‘Ireland Ranked among Best for Covid-19 Innovative Solutions’. The Irish Times. Accessed 7 September 2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/business/innovation/ireland-ranked-among-best-for-covid-19-innovative-solutions-1.4233471.

-

-

www.ezekielemanuel.com www.ezekielemanuel.com

-

COVID-19 Activity Risk Levels. (n.d.). Ezekiel Emanuel | COVID-19 Activity Risk Levels. Retrieved July 8, 2020, from http://www.ezekielemanuel.com/writing/all-articles/2020/06/30/covid-19-activity-risk-levels

-

- Aug 2020

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Couture, V., Dingel, J. I., Green, A. E., Handbury, J., & Williams, K. R. (2020). Measuring Movement and Social Contact with Smartphone Data: A Real-Time Application to COVID-19 (Working Paper No. 27560; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27560

-

-

-

Carl, N. (2020). An Analysis of COVID-19 Mortality at the Local Authority Level in England. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/dmc2v

-

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Lewis, D., Mertens, K., & Stock, J. H. (2020). U.S. Economic Activity During the Early Weeks of the SARS-Cov-2 Outbreak (Working Paper No. 26954; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26954

-

-

jamanetwork.com jamanetwork.com

-

Khan MS, Fonarow GC, Friede T, et al. Application of the Reverse Fragility Index to Statistically Nonsignificant Randomized Clinical Trial Results. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2012469. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12469

-

-

www.alleghenycounty.us www.alleghenycounty.us

-

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

-

Brown, C. S., Ravallion, M., & van de Walle, D. (2020). Can the World’s Poor Protect Themselves from the New Coronavirus? (Working Paper No. 27200; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27200

-

- Jul 2020

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Cavallo, A. (2020). Inflation with Covid Consumption Baskets (Working Paper No. 27352; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27352

-

-

epjdatascience.springeropen.com epjdatascience.springeropen.com

-

Fatehkia, M., Tingzon, I., Orden, A., Sy, S., Sekara, V., Garcia-Herranz, M., & Weber, I. (2020). Mapping socioeconomic indicators using social media advertising data. EPJ Data Science, 9(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-020-00235-w

-

- Jun 2020

-

ec.europa.eu ec.europa.eu

-

malinja. (2015, June 18). Human Capital and Digital Skills [Text]. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future - European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/human-capital

-

- May 2020

-

-

Borgonovi, F., & Pokropek, A. (2020). Can we rely on trust in science to beat the COVID-19 pandemic? [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/yq287

-

-

www.economicmodeling.com www.economicmodeling.com

-

COVID-19 Health Risk Index Paper. (n.d.). Emsi. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from http://www.economicmodeling.com/covid-19-health-risk-index-paper/

-

-

www.zillow.com www.zillow.com

-

www.socialwork.pitt.edu www.socialwork.pitt.edu

- Apr 2020

-

-

Wang, T., Chen, X., Zhang, Q., & Jin, X. (2020, April 26). Use of Internet data to track Chinese behavior and interest in COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/j6m8q

-

- Dec 2019

-

www.dougengelbart.org www.dougengelbart.org

-

One need arose quite commonly as trains of thought would develop on a growing series of note cards. There was no convenient way to link these cards together so that the train of thought could later be recalled by extracting the ordered series of notecards. An associative-trail scheme similar to that out lined by Bush for his Memex could conceivably be implemented with these cards to meet this need and add a valuable new symbol-structuring process to the system.

-

An example of this general sort of thing was given by Bush where he points out that the file index can be called to view at the push of a button, which implicitly provides greater capability to work within more sophisticated and complex indexing systems

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Oct 2019

-

-

Index types are really handy when you have an object that could have unknown keys. They're also handy when using an object as a dictionary or associative array. They do have some downsides, though. You can't specify what keys can be used, and the syntax is also a bit verbose, in my opinion. TypeScript provides a solution, however; the Record utility.

-

-

www.typescriptlang.org www.typescriptlang.org

-

With index types, you can get the compiler to check code that uses dynamic property names.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

www.jsoftware.com www.jsoftware.com

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Aug 2019

-

github.com github.com

-

github.com github.com

- Jun 2019

-

www.asindexing.org www.asindexing.org

-

However, indexes in the modern sense, giving exact locations of names and subjects in a book, were not compiled in antiquity, and only very few seem to have been made before the age of printing. There are several reasons for this. First, as long as books were written in the form of scrolls, there were neither page nor leaf numbers not line counts (as we have them now for classical texts). Also, even had there been such numerical indicators, it would have been impractical to append an index giving exact references, because in order for a reader to consult the index, the scroll would have to be unrolled to the very end and then to be rolled back to the relevant page. (Whoever has had to read a book available only on microfilm, the modern successor of the papyrus scroll, will have experienced how difficult and inconvenient it is to go from the index to the text.) Second, even though popular works were written in many copies (sometimes up to several hundreds),no two of them would be exactly the same, so that an index could at best have been made to chapters or paragraphs, but not to exact pages. Yet such a division of texts was rarely done (the one we have now for classical texts is mostly the work of medieval and Renaissance scholars). Only the invention of printing around 1450 made it possible to produce identical copies of books in large numbers, so that soon afterwards the first indexes began to be compiled, especially those to books of reference, such as herbals. (pages 164-166) Index entries were not always alphabetized by considering every letter in a word from beginning to end, as people are wont to do today. Most early indexes were arranged only by the first letter of the first word, the rest being left in no particular order at all. Gradually, alphabetization advanced to an arrangement by the first syllable, that is, the first two or three letters, the rest of an entry still being left unordered. Only very few indexes compiled in the 16th and early 17th centuries had fully alphabetized entries, but by the 18th century full alphabetization became the rule... (p. 136) (For more information on the subject of indexes, please see Professor Wellisch's Indexing from A to Z, which contains an account of an indexer being punished by having his ears lopped off, a history of narrative indexing, an essay on the zen of indexing, and much more. Please, if you quote from this page, CREDIT THE AUTHOR. Thanks.) Indexes go way back beyond the 17th century. The Gerardes Herbal from the 1590s had several fascinating indexes according to Hilary Calvert. Barbara Cohen writes that the alphabetical listing in the earliest ones only went as far as the first letter of the entry... no one thought at first to index each entry in either letter-by-letter or word-by-word order. Maja-Lisa writes that Peter Heylyn's 1652 Cosmographie in Four Bookes includes a series of tables at the end. They are alphabetical indexes and he prefaces them with "Short Tables may not seeme proportionalble to so long a Work, expecially in an Age wherein there are so many that pretend to learning, who study more the Index then they do the Book."

-

Pliny the Elder (died 79 A.D.) wrote a massive work called The Natural History in 37 Books. It was a kind of encyclopedia that comprised information on a wide range of subjects. In order to make it a bit more user friendly, the entire first book of the work is nothing more than a gigantic table of contents in which he lists, book by book, the various subjects discussed. He even appended to each list of items for each book his list of Greek and Roman authors used in compiling the information for that book. He indicates in the very end of his preface to the entire work that this practice was first employed in Latin literature by Valerius Soranus, who lived during the last part of the second century B.C. and the first part of the first century B.C. Pliny's statement that Soranus was the first in Latin literature to do this indicates that it must have already been practiced by Greek writers.

-

- Aug 2018

-

forumvirium.fi forumvirium.fi

-

The Kalasatama Wellbeing programme is piloting Wellness Foundry's MealLogger app in collaboration with the programme’s partner, Kesko occupational health care services.

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

30.40

30.40

-

3,011.00

3011

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

Health Care System Index: 85.85

85.85

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

Safety Index: 36.52

36.52

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

Safety Index: 76.31

76.31

Tags

Annotators

URL