Author Response

Reviewer #1:

Hutchings et al. report an updated cryo-electron tomography study of the yeast COP-II coat assembled around model membranes. The improved overall resolution and additional compositional states enabled the authors to identify new domains and interfaces--including what the authors hypothesize is a previously overlooked structural role for the SEC31 C-Terminal Domain (CTD). By perturbing a subset of these new features with mutants, the authors uncover some functional consequences pertaining to the flexibility or stability of COP-II assemblies.

Overall, the structural and functional work appears reliable, but certain questions and comments should be addressed prior to publication. However, this reviewer failed to appreciate the conceptual advance that warrants publication in a general biology journal like eLIFE. Rather, this study provides a valuable refinement of our understanding of COP-II that I believe is better suited to a more specialized, structure-focused journal.

We agree that in our original submission our description of the experimental setup, indeed similar to previous work, did not fully capture the novel findings of this paper. Rather than being simply a higher resolution structure of the COPII coat, in fact we have discovered new interactions in the COPII assembly network, and we have probed their functional roles, significantly changing our understanding of the mechanisms of COPII-mediated membrane curvature. In the revised submission we have included additional genetic data that further illuminate this mechanism, and have rewritten the text to better communicate the novel aspects of our work.

Our combination of structural, functional and genetic analyses goes beyond refining our textbook understanding of the COPII coat as a simple ‘adaptor and cage’, but rather it provides a completely new picture of how dynamic regulation of assembly and disassembly of a complex network leads to membrane remodelling.

These new insights have important implications for how coat assembly provides structural force to bend a membrane but is still able to adapt to distinct morphologies. These questions are at the forefront of protein secretion, where there is debate about how different types of carriers might be generated that can accommodate cargoes of different size.

Major Comments:

1) The authors belabor what this reviewer thinks is an unimportant comparison between the yeast reconstruction of the outer coat vertex with prior work on the human outer coat vertex. Considering the modest resolution of both the yeast and human reconstructions, the transformative changes in cryo-EM camera technology since the publication of the human complex, and the differences in sample preparation (inclusion of the membrane, cylindrical versus spherical assemblies, presence of inner coat components), I did not find this comparison informative. The speculations about a changing interface over evolutionary time are unwarranted and would require a detailed comparison of co-evolutionary changes at this interface. The simpler explanation is that this is a flexible vertex, observed at low resolution in both studies, plus the samples are very different.

We do agree that our proposal that the vertex interface changes over evolutionary time is speculative and we have removed this discussion. We agree that a co-evolutionary analysis will be enlightening here, but is beyond the scope of the current work.

We respectfully disagree with the reviewer’s interpretation that the difference between the two vertices is due to low resolution. The interfaces are clearly different, and the resolutions of the reconstructions are sufficient to state this. The reviewer’s suggestion that the difference in vertex orientation might be simply attributable to differences in sample, such as inclusion of the membrane, cylindrical versus spherical morphology, or presence of inner coat components were ruled out in our original submission: we resolved yeast vertices on spherical vesicles (in addition to those on tubes) and on membrane-less cages. These analyses clearly showed that neither the presence of a membrane, nor the change in geometry (tubular vs. spherical) affect vertex interactions. These experiments are presented in Supplementary Fig 4 (Supplementary Fig. 3 in the original version). Similarly, we discount that differences might be due to the presence or absence of inner coat components, since membrane-less cages were previously solved in both conditions and are no different in terms of their vertex structure (Stagg et al. Nature 2006 and Cell 2008).

We believe it is important to report on the differences between the two vertex structures. Nevertheless, we have shifted our emphasis on the functional aspects of vertex formation and moved the comparison between the two vertices to the supplement.

2) As one of the major take home messages of the paper, the presentation and discussion of the modeling and assignment of the SEC31-CTD could be clarified. First, it isn't clear from the figures or the movies if the connectivity makes sense. Where is the C-terminal end of the alpha-solenoid compared to this new domain? Can the authors plausibly account for the connectivity in terms of primary sequence? Please also include a side-by-side comparison of the SRA1 structure and the CTD homology model, along with some explanation of the quality of the model as measured by Modeller. Finally, even if the new density is the CTD, it isn't clear from the structure how this sub-stoichiometric and apparently flexible interaction enhances stability. Hence, when the authors wrote "when the [CTD] truncated form was the sole copy of Sec31 in yeast, cells were not viable, indicating that the novel interaction we detect is essential for COPII coat function." Maybe, but could this statement be a leap to far? Is it the putative interaction essential, or is the CTD itself essential for reasons that remain to be fully determined?

The CTD is separated from the C-terminus of the alpha solenoid domain by an extended domain (~350 amino acids) that is predicted to be disordered, and contains the PPP motifs and catalytic fragment that contact the inner coat. This is depicted in cartoon form in Figures 3A and 7, and discussed at length in the text. This arrangement explains why no connectivity is seen, or expected. We could highlight the C-terminus of the alpha-solenoid domain to emphasize where the disordered region should emerge from the rod, but connectivity of the disordered domain to the CTD could arise from multiple positions, including from an adjacent rod.

The reviewer’s point about the essentiality of the CTD being independent of its interaction with the Sec31 rod, is an important one. The basis for our model that the CTD enhances stability or rigidity of the coat is the yeast phenotype of Sec31-deltaCTD, which resembles that of a sec13 null. Both mutants are lethal, but rescued by deletion of emp24, which leads to more easily deformable membranes (Čopič et al. Science 2012). We agree that even if this model is true, the interaction of the CTD with Sec31 that our new structure reveals is not proven to drive rigidity or essentiality. We have tempered this hypothesis and added alternative possibilities to the discussion.

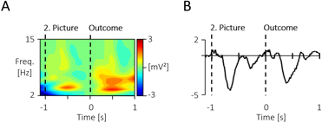

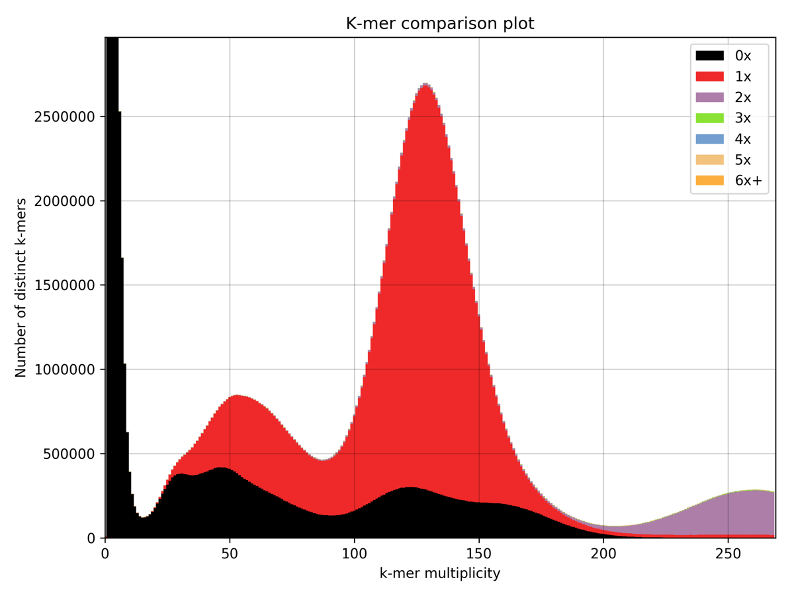

We have included the SRA1 structure in Supplementary Fig 5, as requested, and the model z-score in the Methods. The Z-score, as calculated by the proSA-web server is -6.07 (see figure below, black dot), and falls in line with experimentally determined structures including that of the template (PDB 2mgx, z-score = -5.38).

3) Are extra rods discussed in Fig. 4 are a curiosity of unclear functional significance? This reviewer is concerned that these extra rods could be an in vitro stoichiometry problem, rather than a functional property of COP-II.

This is an important point, that, as we state in the paper, cannot be answered at the moment: the resolution is too low to identify the residues involved in the interaction. Therefore we are hampered in our ability to assess the physiological importance of this interaction. We still believe the ‘extra’ rods are an important observation, as they clearly show that another mode of outer coat interaction, different from what was reported before, is possible.

The concern that interactions visualised in vitro might not be physiologically relevant is broadly applicable to structural biology approaches. However, our experimental approach uses samples that result from active membrane remodelling under near-physiological conditions, and we therefore expect these to be less prone to artefacts than most in vitro reconstitution approaches, where proteins are used at high concentrations and in high salt buffer conditions.

4) The clashsccore for the PDB is quite high--and I am dubious about the reliability of refining sidechain positions with maps at this resolution. In addition to the Ramchandran stats, I would like to see the Ramachandran plot as well as, for any residue-level claims, the density surrounding the modeled side chain (e.g. S742).

The clashscore is 13.2, which, according to molprobity, is in the 57th percentile for all structures and in the 97th for structures of similar resolutions. We would argue therefore that the clashscore is rather low.

In fact, the model was refined from crystal structures previously obtained by other groups, which had worse clashscore (17), despite being at higher resolution. Our refinement has therefore improved the clashscore.

During refinement we have chosen restraint levels appropriate to the resolution of our map (Afonine et al., Acta Cryst D 2018)

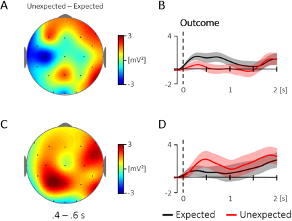

The Ramachandran plot is copied here and could be included in a supplemental figure if required. We make only one residue-level claim (S742), the density for which is indeed not visible at our resolution. We claim that S742 is close to the Sec23-23 interface, and do not propose any specific interactions. Nevertheless we have removed reference to S742 from the manuscript. We included this specific information because of the potential importance of this residue as a site of phosphorylation, thereby putting this interface in broader context for the general eLife reader.

Minor Comments:

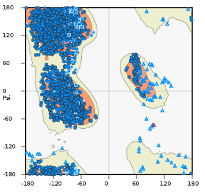

1) The authors wrote "To assess the relative positioning of the two coat layers, we analysed the localisation of inner coat subunits with respect to each outer coat vertex: for each aligned vertex particle, we superimposed the positions of all inner coat particles at close range, obtaining the average distribution of neighbouring inner coat subunits. From this 'neighbour plot' we did not detect any pattern, indicating random relative positions. This is consistent with a flexible linkage between the two layers that allows adaptation of the two lattices to different curvatures (Supplementary Fig 1E)." I do not understand this claim, since the pattern both looks far from random and the interactions depend on molecular interactions that are not random. Please clarify.

We apologize for the confusion: the pattern of each of the two coats are not random. Our sentence refers to the positions of inner and outer coats relative to each other. The two lattices have different parameters and the two layers are linked by flexible linkers (the 350 amino acids referred to above). We have now clarified the sentence.

2) Related to major point #1, the author wrote "We manually picked vertices and performed carefully controlled alignments." I do now know what it means to carefully control alignments, and fear this suggests human model bias.

We used different starting references for the alignments, with the precise aim to avoid model bias. For both vesicle and cage vertex datasets, we have aligned the subtomograms against either the vertex obtained from tubules, or the vertex from previously published membrane-less cages. In all cases, we retrieved a structure that resembles the one on tubules, suggesting that the vertex arrangement we observe isn’t simply the result of reference bias. This procedure is depicted in Supplementary Fig 4 (Supplementary Fig. 3 in the original manuscript), but we have now clarified it also in the methods section.

3) Why do some experiments use EDTA? I may be confused, but I was surprised to see the budding reaction employed 1mM GMPPNP, and 2.5mM EDTA (but no Magnesium?). Also, for the budding reaction, please replace or expand upon the "the 10% GUV (v/v)" with a mass or molar lipid-to-protein ratio.

We regret the confusion. As stated in the methods, all our budding reactions are performed in the presence of EDTA and Magnesium, which is present in the buffer (at 1.2 mM). The reason is to facilitate nucleotide exchange, as reported and validated in Bacia et al., Scientific Reports 2011.

Lipids in GUV preparations are difficult to quantify. We report the stock concentrations used, but in each preparation the amount of dry lipid that forms GUVs might be different, as is the concentration of GUVs after hydration. However since we analyse reactions where COPII proteins have bound and remodelled individual GUVs, we do not believe the protein/lipid ratio influences our structures.

4) Please cite the AnchorMap procedure.

We cite the SerialEM software, and are not aware of other citations specifically for the anchor map procedure.

5) Please edit for typos (focussing, functionl, others)

Done

Reviewer #2:

The manuscript describes new cryo-EM, biochemistry, and genetic data on the structure and function of the COPII coat. Several new discoveries are reported including the discovery of an extra density near the dimerization region of Sec13/31, and "extra rods" of Sec13/31 that also bind near the dimerization region. Additionally, they showed new interactions between the Sec31 C-terminal unstructured region and Sec23 that appear to bridge multiple Sec23 molecules. Finally, they increased the resolution of the Sec23/24 region of their structure compared to their previous studies and were able to resolve a previously unresolved L-loop in Sec23 that makes contact with Sar1. Most of their structural observations were nicely backed up with biochemical and genetic experiments which give confidence in their structural observations. Overall the paper is well-written and the conclusions justified.

However, this is the third iteration of structure determination of the COPII coat on membrane with essentially the same preparation and methods. Each time, there has been an incremental increase in resolution and new discoveries, but the impact of the present study is deemed to be modest. The science is good, but it may be more appropriate for a more specialized journal. Areas of specific concern are described below.

As described above, we respectfully disagree with this interpretation of the advance made by the current work. This work improves on previous work in many aspects. The resolution of the outer coat increases from over 40A to 10-12A, allowing visualisation of features that were not previously resolved, including a novel vertex arrangement, the Sec31 CTD, and the outer coat ‘extra rods’. An improved map of the inner coat also allows us to resolve the Sec23 ‘L-loop’. We would argue that these are not just extra details, but correspond to a suite of novel interactions that expand our understanding of the complex COPII assembly network. Moreover, we include biochemical and genetic experiments that not only back up our structural observations but bring new insights into COPII function. As pointed out in response to reviewer 1, we believe our work contributes a significant conceptual advance, and have modified the manuscript to convey this more effectively.

1) The abstract is vague and should be re-written with a better description of the work.

We have modified the abstract to specifically outline what we have done and the major new discoveries of this paper.

2) Line 166 - "Surprisingly, this mutant was capable of tubulating GUVs". This experiment gets to one of the fundamental unknown questions in COPII vesiculation. It is not clear what components are driving the membrane remodeling and at what stages during vesicle formation. Isn't it possible that the tubulation activity the authors observe in vitro is not being driven at all by Sec13/31 but rather Sec23/24-Sar1? Their Sec31ΔCTD data supports this idea because it lacks a clear ordered outer coat despite making tubules. An interesting experiment would be to see if tubules form in the absence of all of Sec13/31 except the disordered domain of Sec31 that the authors suggest crosslinks adjacent Sec23/24s.

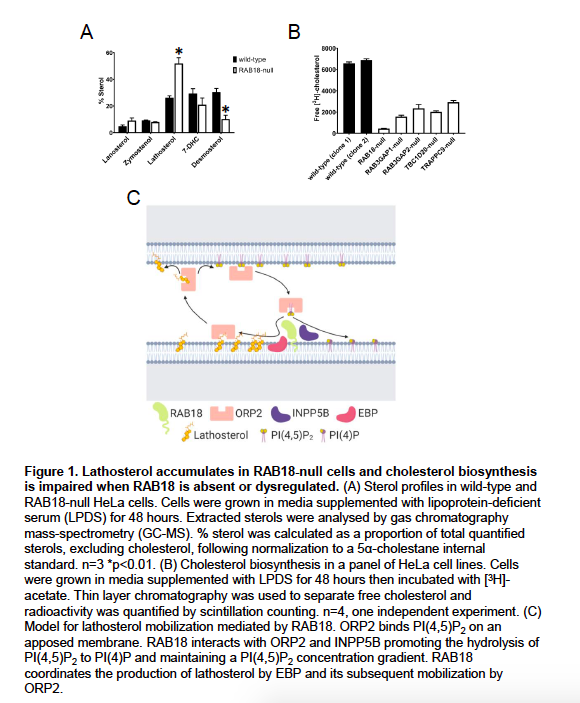

This is an astute observation, and we agree with the reviewer that the source of membrane deformation is not fully understood. We favour the model that budding is driven significantly by the Sec23-24 array. To further support this, we have performed a new experiment, where we expressed Sec31ΔN in yeast cells lacking Emp24, which have more deformable membranes and are tolerant to the otherwise lethal deletion of Sec13. While Sec31ΔN in a wild type background did not support cell viability, this was rescued in a Δemp24 yeast strain, strongly supporting the hypothesis that a major contributor to membrane remodelling is the inner coat, with the outer coat becoming necessary to overcome membrane bending resistance that ensues from the presence of cargo. We now include these results in Figure 1.

However, we must also take into account the results presented in Fig. 6, where we show that weakening the Sec23-24 interface still leads to budding, but only if Sec13-31 is fully functional, and that in this case budding leads to connected pseudo-spherical vesicles rather than tubes. When Sec13-31 assembly is also impaired, tubes appear unstructured. We believe this strongly supports our conclusions that both inner and outer coat interactions are fundamental for membrane remodelling, and it is the interplay between the two that determines membrane morphology (i.e. tubes vs. spheres).

To dissect the roles of inner and outer coats even further, we have done the experiment that the reviewer suggests: we expressed Sec31768-1114, but the protein was not well-behaved and co-purified with chaperones. We believe the disordered domain aggregates when not scaffolded by the structured elements of the rod. Nonetheless, we used this fragment in a budding reaction, and could not see any budding. We did not include this experiment as it was inconclusive: the lack of functionality of the purified Sec31 fragment could be attributed to the inability of the disordered region to bind its inner coat partner in the absence of the scaffolding Sec13-31 rod. As an alternative approach, we have used a version of Sec31 that lacks the CTD, and harbours a His tag at the N-terminus (known from previous studies to partially disrupt vertex assembly). We think this construct is more likely to be near native, since both modifications on their own lead to functional protein. We could detect no tubulation with this construct by negative stain, while both control constructs (Sec31ΔCTD and Nhis-Sec31) gave tubulation. This suggests that the cross-linking function of Sec31 is not sufficient to tubulate GUV membranes, but some degree of functional outer coat organisation (either mediated by N- or C-terminal interactions) is needed. It is also possible that the lack of outer coat organisation might lead to less efficient recruitment to the inner coat and cross-linking activity. We have added this new observation to the manuscript.

3) Line 191 - "Inspecting cryo-tomograms of these tubules revealed no lozenge pattern for the outer 192 coat" - this phrasing is vague. The reviewer thinks that what they mean is that there is a lack of order for the Sec13/31 layer. Please clarify.

The reviewer is correct, we have changed the sentence.

4) Line 198 - "unambiguously confirming this density corresponds to 199 the CTD." This only confirms that it is the CTD if that were the only change and the Sec13/31 lattice still formed. Another possibility is that it is density from other Sec13/31 that only appears when the lattice is formed such as the "extra rods". One possibility is that the density is from the extra rods. The reviewer agrees that their interpretation is indeed the most likely, but it is not unambiguous. The authors should consider cross-linking mass spectrometry.

We have removed the word ‘unambiguously’, and changed to ‘confirming that this density most likely corresponds to the CTD’. Nonetheless, we believe that our interpretation is correct: the extra rods bind to a different position, and themselves also show the CTD appendage. In this experiment, the lack of the CTD was the only biochemical change.

5) In the Sec31ΔCTD section, the authors should comment on why ΔCTD is so deleterious to oligomer organization in yeast when cages form so abundantly in preparations of human Sec13/31 ΔC (Paraan et al 2018).

We have added a comment to address this. “Interestingly, human Sec31 proteins lacking the CTD assemble in cages, indicating that either the vertex is more stable for human proteins and sufficient for assembly, or that the CTD is important in the context of membrane budding but not for cage formation in high salt conditions.”

6) The data is good for the existence of the "extra rods", but significance and importance of them is not clear. How can these extra densities be distinguished from packing artifacts due to imperfections in the helical symmetry.

Please also see our response to point 3 from reviewer 1. Regarding the specific concern that artefacts might be a consequence of imperfection in the helical symmetry, we would argue such imperfections are indeed expected in physiological conditions, and to a much higher extent. For this reason interactions seen in the context of helical imperfections are likely to be relevant. In fact, in normal GTP hydrolysis conditions, we expect long tubes would not be able to form, and the outer coat to be present on a wide range of continuously changing membrane curvatures. We think that the ability of the coat to form many interactions when the symmetry is imperfect might be exactly what confers the coat its flexibility and adaptability.

7) Figure 5 is very hard to interpret and should be redone. Panels B and C are particularly hard to interpret.

We have made a new figure where we think clarity is improved.

8) The features present in Sec23/24 structure do not reflect the reported resolution of 4.7 Å. It seems that the resolution is overestimated.

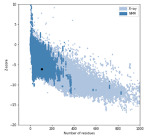

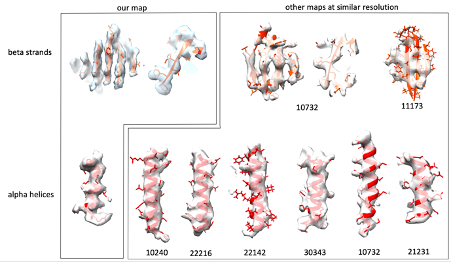

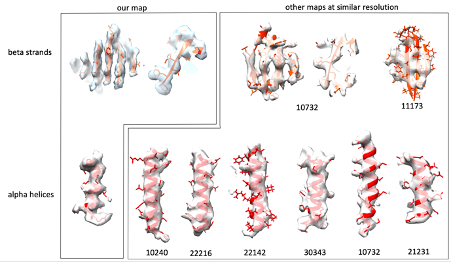

We report an average resolution of 4.6 Å. In most of our map we can clearly distinguish beta strands, follow the twist of alpha helices and see bulky side chains. These features typically become visible at 4.5-5A resolution. We agree that some areas are worse than 4.6 Å, as typically expected for such a flexible assembly, but we believe that the average resolution value reported is accurate. We obtained the same resolution estimate using different software including relion, phenix and dynamo, so that is really the best value we can provide. To further convince ourselves that we have the resolution we claim, we sampled EM maps from the EMDB with the same stated resolution (we just took the 7 most recent ones which had an associated atomic model), and visualised their features at arbitrary positions. For both beta strands and alpha helices, we do not feel our map looks any worse than the others we have examined. We include a figure here.

9) Lines 315/316 - "We have combined cryo-tomography with biochemical and genetic assays to obtain a complete picture of the assembled COPII coat at unprecedented resolution (Fig. 7)"

10) Figure 7. is a schematic model/picture the authors should reference a different figure or rephrase the sentence.

We now refer to Fig 7 in a more appropriate place.

Reviewer #3:

The manuscript by Hutchings et al. describes several previously uncharacterised molecular interactions in the coats of COP-II vesicles by using a reconstituted coats of yeast COPI-II. They have improved the resolution of the inner coat to 4.7A by tomography and subtomogram averaging, revealing detailed interactions, including those made by the so-called L-loop not observed before. Analysis of the outer layer also led to new interesting discoveries. The sec 31 CTD was assigned in the map by comparing the WT and deletion mutant STA-generated density maps. It seems to stabilise the COP-II coats and further evidence from yeast deletion mutants and microsome budding reconstitution experiments suggests that this stabilisation is required in vitro. Furthermore, COP-II rods that cover the membrane tubules in right-handed manner revealed sometimes an extra rod, which is not part of the canonical lattice, bound to them. The binding mode of these extra rods (which I refer to here a Y-shape) is different from the canonical two-fold symmetric vertex (X-shape). When the same binding mode is utilized on both sides of the extra rod (Y-Y) the rod seems to simply insert in the canonical lattice. However, when the Y-binding mode is utilized on one side of the rod and the X-binding mode on the other side, this leads to bridging different lattices together. This potentially contributes to increased flexibility in the outer coat, which maybe be required to adopt different membrane curvatures and shapes with different cargos. These observations build a picture where stabilising elements in both COP-II layers contribute to functional cargo transport. The paper makes significant novel findings that are described well. Technically the paper is excellent and the figures nicely support the text. I have only minor suggestions that I think would improve the text and figure.

We thank the reviewer for helpful suggestions which we agree improve the manuscript.

Minor Comments:

L 108: "We collected .... tomograms". While the meaning is clear to a specialist, this may sound somewhat odd to a generic reader. Perhaps you could say "We acquired cryo-EM data of COP-II induced tubules as tilt series that were subsequently used to reconstruct 3D tomograms of the tubules."

We have changed this as suggested

L 114: "we developed an unbiased, localisation-based approach". What is the part that was developed here? It seems that the inner layer particle coordinates where simply shifted to get starting points in the outer layer. Developing an approach sounds more substantial than this. Also, it's unclear what is unbiased about this approach. The whole point is that it's biased to certain regions (which is a good thing as it incorporates prior knowledge on the location of the structures).

We have modified the sentence to “To target the sparser outer coat lattice for STA, we used the refined coordinates of the inner coat to locate the outer coat tetrameric vertices”, and explain the approach in detail in the methods.

L 124: "The outer coat vertex was refined to a resolution of approximately ~12 A, revealing unprecedented detail of the molecular interactions between Sec31 molecules (Supplementary Fig 2A)". The map alone does not reveal molecular interactions; the main understanding comes from fitting of X-ray structures to the low-resolution map. Also "unprecedented detail" itself is somewhat problematic as the map of Noble et al (2013) of the Sec31 vertex is also at nominal resolution of 12 A. Furthermore, Supplementary Fig 2A does not reveal this "unprecedented detail", it shows the resolution estimation by FSC. To clarify, these points you could say: "Fitting of the Sec31 atomic model to our reconstruction vertex at 12-A resolution (Supplementary Fig 2A) revealed the molecular interactions between different copies of Sec31 in the membrane-assembled coat.

We have changed the sentence as suggested.

L 150: Can the authors exclude the possibility that the difference is due to differences in data processing? E.g. how the maps amplitudes have been adjusted?

Yes, we can exclude this scenario by measuring distances between vertices in the right and left handed direction. These measurements are only compatible with our vertex arrangement, and cannot be explained by the big deviation from 4-fold symmetry seen in the membrane-less cage vertices.

L 172: "that wrap tubules either in a left- or right-handed manner". Don't they do always both on each tubule? Now this sentence could be interpreted to mean that some tubules have a left-handed coat and some a right-handed coat.

We have changed this sentence to clarify. “Outer coat vertices are connected by Sec13-31 rods that wrap tubules both in a left- and right-handed manner.”

L276: "The difference map" hasn't been introduced earlier but is referred to here as if it has been.

We now introduce the difference map.

L299: Can "Secondary structure predictions" denote a protein region "highly prone to protein binding"?

Yes, this is done through DISOPRED3, a feature include in the PSIPRED server we used for our predictions. The reference is: Jones D.T., Cozzetto D. DISOPRED3: precise disordered region predictions with annotated protein-binding activity Bioinformatics. 2015; 31:857–863. We have now added this reference to the manuscript.

L316: It's true that the detail in the map of the inner coat is unprecedented and the model presented in Figure 7 is partially based on that. But here "unprecedented resolution" sounds strange as this sentence refers to a schematic model and not a map.

We have changed this by moving the reference to Fig 7 to a more appropriate place

L325: "have 'compacted' during evolution" -> remove. It's enough to say it's more compact in humans and less compact in yeast as there could have been different adaptations in different organisms at this interface.

We have changed as requested. See also our response to reviewer 1, point 1.

L327: What's exactly meant by "sequence diversity or variability at this density".

We have now clarified: “Since multiple charge clusters in yeast Sec31 may contribute to this interaction interface (Stancheva et al., 2020), the low resolution could be explained by the fact that the density is an average of different sequences.”

L606-607: The description of this custom data processing approach is difficult to follow. Why is in-plane flip needed and how is it used here?

Initially particles are picked ignoring tube directionality (as this cannot be assessed easily from the tomograms due to the pseudo-twofold symmetry of the Sec23/24/Sar1 trimer). So the in plane rotation of inner coat subunit could be near 0 or 180°. For each tube, both angles are sampled (in-plane flip). Most tubes result in the majority of particles being assigned one of the two orientations (which is then assumed as the tube directionality). Particles that do not conform are removed, and rare tubes where directionality cannot be determined are also removed. We have re-written the description to clarify these points: “Initial alignments were conducted on a tube-by-tube basis using the Dynamo in-plane flip setting to search in-plane rotation angles 180° apart. This allowed to assign directionality to each tube, and particles that were not conforming to it were discarded by using the Dynamo dtgrep_direction command in custom MATLAB scripts”

L627: "Z" here refers to the coordinate system of aligned particles not that of the original tomogram. Perhaps just say "shifted 8 pixels further away from the membrane".

Changed as requested.

L642-643: How can the "left-handed" and "right-handed" rods be separated here? These terms refer to the long-range organisation of the rods in the lattice it's not clear how they were separated in the early alignments.

They are separated by picking only one subset using the dynamo sub-boxing feature. This extracts boxes from the tomogram which are in set positions and orientation relative to the average of previously aligned subtomograms. From the average vertex structure, we sub-box rods at 4 different positions that correspond to the centre of the rods, and the 2-fold symmetric pairs are combined into the same dataset. We have clarified this in the text: “The refined positions of vertices were used to extract two distinct datasets of left and right-handed rods respectively using the dynamo sub-boxing feature.”

Figure 2B. It's difficult to see the difference between dark and light pink colours.

We have changed colours to enhance the difference.

Figure 3C. These panels report the relative frequency of neighbouring vertices at each position; "intensity" does not seem to be the right measure for this. You could say that the colour bar indicates the "relative frequency of neighbouring vertices at each position" and add detail how the values were scaled between 0 and 1. The same applies to SFigure 1E.

Changed as requested.

Figure 4. The COP-II rods themselves are relatively straight, and they are not left-handed or right-handed. Here, more accurate would be "architecture of COPII rods organised in a left-handed manner". (In the text the authors may of course define and then use this shorter expression if they so wish.) Panel 4B top panel could have the title "left-handed" and the lower panel should have the title "right-handed" (for consistency and clarity).

We have now defined left- and right-handed rods in the text, and have changed the figure and panel titles as requested.