Tseng, H. F., Ackerson, B. K., Luo, Y., Sy, L. S., Talarico, C. A., Tian, Y., Bruxvoort, K. J., Tubert, J. E., Florea, A., Ku, J. H., Lee, G. S., Choi, S. K., Takhar, H. S., Aragones, M., & Qian, L. (2022). Effectiveness of mRNA-1273 against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants. Nature Medicine, 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01753-y

- Feb 2022

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

-

Claudia Kemfert geht in diesem auch sonst sehr hörenswerten Podcast ausführlich darauf ein, dass sich Deutschland in eine selbstverschuldete Abhängigkeit von russischen Gaslieferungen gebracht hat. Dabei haben sie selbst und andere über Jahren in Gutachten gezeigt, dass es ökologisch und politisch bessere Alternativen zu den Gaspipelines aus Russland gab. Man muss daraus den Schluss ziehen, dass sich hier Kräfte durchgesetzt haben, in deren Interesse die Abhängigkeit von den Fossilbrennstoffen aus Russland ist—eine Koalition aus russischen Oligarchen und ihren Verbündeten in Deutschland.

-

-

thehustle.co thehustle.co

-

“When I moved to Kansas,” Roberts said, “I was like, ‘holy shit, they’re giving stuff away.’”

This sounds great, but what are the "costs" on the other side? How does one balance out the economics of this sort of housing situation versus amenities supplied by a community in terms of culture, health, health care, interaction, etc.? Is there a maximum on a curve to be found here? Certainly in some places one is going to overpay for this basket of goods (perhaps San Francisco?) where in others one may underpay. Does it have anything to do with the lifecycle of cities and their governments? If so, how much?

-

- Jan 2022

-

notesfromasmallpress.substack.com notesfromasmallpress.substack.com

-

If booksellers like to blame publishers for books not being available, publishers like to blame printers for being backed up. Who do printers blame? The paper mill, of course.

The problem with capitalism is that in times of fecundity things can seem to magically work so incredibly well because so much of the system is hidden, yet when problems arise so much becomes much more obvious.

Unseen during fecundity is the amount of waste and damage done to our environments and places we live. Unseen are the interconnections and the reliances we make on our environment and each other.

There is certainly a longer essay hiding in this idea.

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Shoss, M., Hootegem, A. V., Selenko, E., & Witte, H. D. (2022). The Job Insecurity of Others: On the Role of Perceived National Job Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/qhpu5

-

- Dec 2021

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Timothy Caulfield. (2021, October 19). Politics is derailing a crucial debate over the immunity you get from recovering from #Covid19 https://statnews.com/2021/10/19/politics-is-derailing-a-crucial-debate-over-the-immunity-you-get-from-recovering-from-covid-19/ @levfacher via @statnews “People on the right scream, so people on the left say no. We’re in this horrible, awful feedback loop of vitriol right now.” [Tweet]. @CaulfieldTim. https://twitter.com/CaulfieldTim/status/1450475493262864393

-

-

-

Hignell, B., Saleemi, Z., & Valentini, E. (2021). The role of emotions on policy support and environmental advocacy. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/45pge

-

- Nov 2021

-

thenarwhal.ca thenarwhal.ca

-

Trans Mountain said there have not been any oil leaks due to the flooding, which has triggered an emergency shutdown of the pipeline lasting longer than any previous stoppage in its nearly 70-year-history.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Like, the world I came to is exactly the same as the world that I left. But what you wouldn't have understood is that every breath that you took contributed to the possibility of countless lives after you - lives that you would never see, lives that we are all a part of today. And it's worth thinking that maybe the meaning of our lives are actually not even within the scope of our understanding.

This is a profound observation that shows how our collective species death over deep history shapes the universe. From a first person experience of reality, however, does it makes us feel that the universe is intimate? The universe is a grand dance and we are part of that dance. Ernest Becker's Mortality Salience looms large. How do we feel meaningful in the face of our mortality? How do we alleviate the perennial meaning crisis?

-

-

osf.io osf.io

-

Chen, W., & Zou, Y. (2021). Why Zoom Is Not Doomed Yet: Privacy and Security Crisis Response in the COVID-19 Pandemic. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/mf935

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

Poultry scientists have also succeeded in selecting for parthenogenesis, increasing the incidence in Beltsville small white turkeys more than threefold, to 41.5 percent in five generations. Environmental factors—like high temperatures or a viral infection—also seem to trigger poultry parthenogenesis.

Parthenogenesis can be selected for in breeding.

What might this look like in other animal models. What do the long term effects of such high percentages potentially look like?

Could this be a tool for guarding against rising temperatures in the looming climate crisis?

-

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

What Morton means by “the end of the world” is that a world view is passing away. The passing of this world view means that there is no “world” anymore. There’s just an infinite expanse of objects, which have as much power to determine us as we have to determine them. Part of the work of confronting strange strangeness is therefore grappling with fear, sadness, powerlessness, grief, despair. “Somewhere, a bird is singing and clouds pass overhead,” Morton writes, in “Being Ecological,” from 2018. “You stop reading this book and look around you. You don’t have to be ecological. Because you are ecological.” It’s a winsome and terrifying idea. Learning to see oneself as an object among objects is destabilizing—like learning “to navigate through a bad dream.” In many ways, Morton’s project is not philosophical but therapeutic. They have been trying to prepare themselves for the seismic shifts that are coming as the world we thought we knew transforms.

We are suffering through a meaning crisis due to the huge impacts humanity has had on the planet. As a result, destabilization is happening exponentially as nature blows back to us.Morton's brutal honesty doesn't leave us with many places to hide. We have to confront what we have collectively created.

-

-

-

Leder, J., Schütz, A., & Pastukhov, A. (Sasha). (2021). Keeping the kids home: Increasing concern for others in times of crisis. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/6s28u

-

- Oct 2021

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Tanis, C., Nauta, F., Boersma, M., Steenhoven, M. van der, Borsboom, D., & Blanken, T. (2021). Practical behavioural solutions to COVID-19: Changing the role of behavioural science in crises. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/q349k

-

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

-

Illari, L., Restrepo, N. J., Leahy, R., Velasquez, N., Lupu, Y., & Johnson, N. F. (2021). Losing the battle over best-science guidance early in a crisis: Covid-19 and beyond. ArXiv:2110.09634 [Nlin, Physics:Physics]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2110.09634

-

-

www.cbc.ca www.cbc.ca

-

Academia: All the Lies: What Went Wrong in the University Model and What Will Come in its Place

“Students are graduating into a brutal job market.”

The entreprecariat is designed for learned helplessness (social: individualism), trained incapacities (economic: specialization), and bureaucratic intransigence (political: authoritarianism).

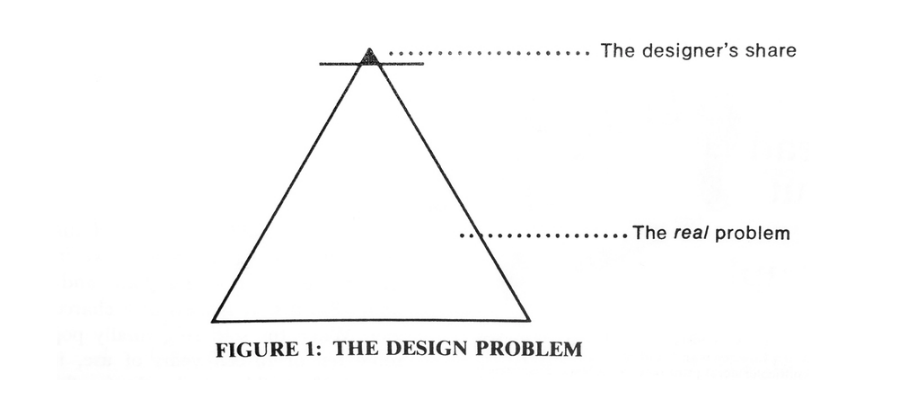

The Design Problem

Three diagrams will explain the lack of social engagement in design. If (in Figure 1) we equate the triangle with a design problem, we readily see that industry and its designers are concerned only with the tiny top portion, without addressing themselves to real needs.

(Design for the Real World, 2019. Page 57.)

The other two figures merely change the caption for the figure.

- Figure 1: The Design Problem

- Figure 2: A Country

- Figure 3: The World

-

-

www.hpvworld.com www.hpvworld.com

-

How Ireland reversed a HPV vaccination crisis. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://www.hpvworld.com/communication/articles/how-ireland-reversed-a-hpv-vaccination-crisis/

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Ghinwa El Hayek on Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved 4 October 2021, from https://twitter.com/GhinwaHayek/status/1411393046017630212

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

Military doctors shore up exhausted health teams in US south amid Covid surge. (2021, September 7). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/sep/07/covid-us-south-military-doctors

-

- Sep 2021

-

www.cbc.ca www.cbc.ca

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

Dehghan, S. K. (2021, September 23). More than 100 countries face spending cuts as Covid worsens debt crisis, report warns. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/sep/23/more-than-100-countries-face-spending-cuts-as-covid-worsens-debt-crisis-report-warns

Tags

- is:news

- social protection

- global south

- debt crisis

- COVID-19

- developing country

- education

- health

- inequality

- lang:en

- spending cut

Annotators

URL

-

-

fs.blog fs.blog

-

No one but Humboldt had looked at the relationship between humankind and nature like this before.

Apparently even with massive globalization since the 1960s, many humans (Americans in particular) are still unable to see our impacts on the world in which we live. How can we make our impact more noticed at the personal and smaller levels? Perhaps this will help to uncover the harms which we're doing to each other and the world around us?

-

- Aug 2021

-

science.sciencemag.org science.sciencemag.org

-

Lund, F. E., & Randall, T. D. (2021). Scent of a vaccine. Science, 373(6553), 397–399. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg9857

-

-

www.thenation.com www.thenation.com

- Jul 2021

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

u/dawnlxh. (2021). Reviewing peer review: does the process need to change, and how?. r/BehSciAsk. Reddit

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Lee, Y. K., Jung, Y., Lee, I., Park, J. E., & Hahn, S. (2021). Building a Psychological Ground Truth Dataset with Empathy and Theory-of-Mind During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mpn3w

-

-

-

Maatman, F. O. (2021). Psychology’s Theory Crisis, and Why Formal Modelling Cannot Solve It. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/puqvs

-

-

www.sandiegouniontribune.com www.sandiegouniontribune.com

-

Facebook, Twitter, options, S. more sharing, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Email, URLCopied!, C. L., & Print. (2021, June 1). Misinformation remains the biggest hurdle as vaccination effort turns to cash incentives. San Diego Union-Tribune. https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/health/story/2021-05-31/misinformation-remains-the-biggest-hurdle-as-vaccination-effort-turns-to-cash-incentives

Tags

- is:news

- health policy

- vaccination

- crisis

- misinformation

- global vaccine distribution

- health

- lang:en

- COVID-19

- vaccine

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.ipcc.ch www.ipcc.ch

-

Limiting warming to 1.5°C implies reaching net zero CO2 emissions globally around 2050 and concurrent deep reductions in emissions of non-CO2 forcers, particularly methane (high confidence). Such mitigation pathways are characterized by energy-demand reductions, decarbonization of electricity and other fuels, electrification of energy end use, deep reductions in agricultural emissions, and some form of CDR with carbon storage on land or sequestration in geological reservoirs.

This is where the net zero by 2050 comes from. Note in this scenario it requires CDR ... plus massive transformations in energy and production systems.

-

Limiting warming to 1.5°C depends on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions over the next decades, where lower GHG emissions in 2030 lead to a higher chance of keeping peak warming to 1.5°C (high confidence). Available pathways that aim for no or limited (less than 0.1°C) overshoot of 1.5°C keep GHG emissions in 2030 to 25–30 GtCO2e yr−1 in 2030 (interquartile range). This contrasts with median estimates for current unconditional NDCs of 52–58 GtCO2e yr−1 in 2030.

i.e. current commitments have 2x the amount of CO2 emitted per year in 2030 that is compatible with 1.5°.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Jun 2021

-

nautil.us nautil.us

-

Levenson, T. (2021, June 23). When a Good Scientist Is the Wrong Source. Nautilus. http://nautil.us/issue/102/hidden-truths/when-a-good-scientist-is-the-wrong-source

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Thomas Rhys Evans on Twitter: “🚨 Get Involved 🚨 #OpenScience practices and preregistration are all well and good, but do they help with applied and consultancy research? 🧵...” / Twitter. (n.d.). Retrieved June 27, 2021, from https://twitter.com/ThomasRhysEvans/status/1395752110088675328

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

van Lange, P., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Human Cooperation and the Crises of Climate Change, COVID-19, and Misinformation [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/6tpa8

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

Prabhala, C. C., Achal. (2021, May 5). Biden Has the Power to Vaccinate the World. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/05/biden-has-power-vaccinate-world/618802/

-

-

extinctionrebellion.uk extinctionrebellion.uk

-

Ultimately, having access to the top political decision makers and using biased studies, the industrial lobbies have managed to sabotage the reforms the Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat called for. A context and tactic we are only too familiar with.

Details? What biased studies? how did they sabotage this?

-

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

Briggs, A., & Vassall, A. (2021). Count the cost of disability caused by COVID-19. Nature, 593(7860), 502–505. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01392-2

-

-

www.reuters.com www.reuters.com

-

Medics march to WHO headquarters in climate campaign | Reuters. (n.d.). Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/medics-march-who-headquarters-climate-campaign-2021-05-29/

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Doctors for XR on Twitter: “https://t.co/OwN3VQsGqw @richardhorton1 speaking to @DrTedros today on video link at #WHA74 about the similarities of #COVID19 and #climatecrisis and the cost of inaction. This before Tedros addressed Doctors + Nurses protesting at the WHO. #WHO #RedAlertWHO https://t.co/yComw7YNR3” / Twitter. (n.d.). Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://twitter.com/DoctorsXr/status/1398656730570145796

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Capraro, V., Boggio, P., Böhm, R., Perc, M., & Sjåstad, H. (2021). Cooperation and acting for the greater good during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/65xmg

-

- May 2021

-

-

India’s Covid crisis hits Covax vaccine-sharing scheme. (2021, May 17). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-57135368

-

-

bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

-

Stevenson, C., Wakefield, J. R. H., Felsner, I., Drury, J., & Costa, S. (n.d.). Collectively coping with coronavirus: Local community identification predicts giving support and lockdown adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Social Psychology, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12457

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Zhou, X., Nguyen-Feng, V. N., Wamser-Nanney, R., & Lotzin, A. (2021). Racism, Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, and Racial Disparity in the U.S. COVID-19 Syndemic [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/rc2ns

-

-

phirephoenix.com phirephoenix.com

-

71% of global emissions can be traced back to 100 companies,

This would seem to fall into the Pareto principle guidelines. How can we minimize the emissions from just these 100 companies?

-

-

www.newscientist.com www.newscientist.com

-

India’s crisis should be a warning against covid-19 complacency. (n.d.). New Scientist. Retrieved May 15, 2021, from https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg25033323-400-indias-crisis-should-be-a-warning-against-covid-19-complacency/

-

-

www.scientificamerican.com www.scientificamerican.com

-

Brazil’s Pandemic Is a “Biological Fukushima” That Threatens the Entire Planet—Scientific American. (n.d.). Retrieved May 12, 2021, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/brazils-pandemic-is-a-lsquo-biological-fukushima-rsquo-that-threatens-the-entire-planet/

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Daly, M., & Robinson, E. (2020). Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/79f5v

-

-

www.sciencemag.org www.sciencemag.org

-

GruberMay. 20, J., 2020, & Pm, 4:50. (2020, May 20). Professors must support the mental health of trainees during the COVID-19 crisis. Science | AAAS. https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2020/05/professors-must-support-mental-health-trainees-during-covid-19-crisis

-

-

-

Luppi, F., Arpino, B., & Rosina, A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on fertility plans in Italy, Germany, France, Spain and UK [Preprint]. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/wr9jb

-

-

www.swissinfo.ch www.swissinfo.ch

-

Keystone-SDA/gw. (n.d.). Emergency care workers urge Swiss government to act as Covid cases soar. SWI Swissinfo.Ch. Retrieved 1 March 2021, from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/emergency-care-workers-urge-swiss-government-to-act-as-covid-cases-surge/46103186

-

-

crookedtimber.org crookedtimber.org

-

Right now, most of the blockchain mining in the world happens in China, where provinces with the cheapest energy set up mining operations to do the ‘proof of work’ calculations that the dominant paradigm of blockchain requires. Factories that ostensibly make other things now acquire significant computing hardware and dedicate energy in order to, essentially, print money that’s then stored offshore. A recent study shows that 40% of China’s mostly bitcoin mining is powered by coal-burning. We also already know that non-blockchain server farms in cheap energy countries consume so much energy they distort national grids, and throw off huge amounts of heat that then need cooling for the servers to operate, creating a vicious cycle of energy consumption

-

-

www.washingtonpost.com www.washingtonpost.com

-

The report underscores how climate misinformation is the next front in the disinformation battles.

-

-

professorsharonpeacock.co.uk professorsharonpeacock.co.uk

-

Long-COVID - the nightmare that won’t end—A researcher’s first hand perspective |Dr Kathy Raven. (2021, February 6). Sharon Peacock. https://professorsharonpeacock.co.uk/long-covid-the-nightmare-that-wont-end-a-first-hand-perspective/

-

-

www.pnas.org www.pnas.org

-

Conley, D., & Johnson, T. (2021). Opinion: Past is future for the era of COVID-19 research in the social sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(13). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104155118

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

r/BehSciAsk—Behavioural science one year on. (n.d.). Reddit. Retrieved May 2, 2021, from https://www.reddit.com/r/BehSciAsk/comments/mw8mdr/behavioural_science_one_year_on/

-

-

-

r/BehSciResearch - Behavioural Science one year on: How did we do? (n.d.). Reddit. Retrieved May 2, 2021, from https://www.reddit.com/r/BehSciResearch/comments/mw8ngy/behavioural_science_one_year_on_how_did_we_do/

-

- Apr 2021

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Ebrahimi, O. V., Johnson, M. S., Ebling, S., Amundsen, O. M., Halsøy, Ø., Hoffart, A., … Johnson, S. U. (2021, April 25). Risk, Trust, and Flawed Assumptions: Vaccine Hesitancy During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/57pwf

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

ReconfigBehSci. (2021, January 1). It is 13 months since the piece on ‘reconfiguring behavioural science’ for crisis knowledge management that led to https://t.co/pIBRAjupO3 What have we learned? What did the behavioural sciences get right? What went wrong? Join the discussion! 1/2 https://t.co/KZg3ugEg6J [Tweet]. @SciBeh. https://twitter.com/SciBeh/status/1385271556436283395

-

-

www.bmj.com www.bmj.com

-

Deer, B. (2011). How the vaccine crisis was meant to make money. BMJ, 342, c5258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5258

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

news.ycombinator.com news.ycombinator.com

-

This project will be great for instruction and portable reproducible science

This is what I'm aiming for with triplescripts.org. Initially, I'm mostly focused on the reproducibility the build process for software. In principle, it can encompass all kinds of use, and I actually want it to, but for practical reasons I'm trying to go for manageable sized bites instead of very large ones.

-

-

www.macleans.ca www.macleans.ca

-

April 8, P. T. & 2021. (2021, April 8). Canada is likely to exceed the U.S. infection rate in the coming days. Macleans.Ca. https://www.macleans.ca/news/canada-likely-to-exceed-u-s-infection-rate-in-coming-days/

-

- Mar 2021

-

www.frontiersin.org www.frontiersin.org

-

Spagnoli, Paola, Carmela Buono, Liliya Scafuri Kovalchuk, Gennaro Cordasco, and Anna Esposito. ‘Perfectionism and Burnout During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Two-Wave Cross-Lagged Study’. Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.631994.

-

-

journals.sagepub.com journals.sagepub.com

-

Lovari, A., Martino, V., & Righetti, N. (2021). Blurred Shots: Investigating the Information Crisis Around Vaccination in Italy. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220910245

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Lopez-Persem, A., Bieth, T., Guiet, S., Ovando-Tellez, M., & Volle, E. (2021). Through thick and thin: Changes in creativity during the first lockdown of the Covid-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/26qde

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Michels, M., Glöckner, A., & Giersch, D. (2020). Personality Psychology in Times of Crisis: Profile-specific Recommendations on how to deal with COVID-19 [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/r9q6g

-

-

forecasters.org forecasters.org

-

Forecasting for COVID-19 has failed. (2020, June 14). International Institute of Forecasters. https://forecasters.org/blog/2020/06/14/forecasting-for-covid-19-has-failed/

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

Zephaniah, B. (2020, May 18). Amid the Covid-19 crisis, I keep thinking about the children in our hospices | Benjamin Zephaniah. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/may/18/covid-19-children-hospices-west-midlands

-

-

-

Stanford, F. S. I. (2020, April 23). Anti-Virus Measures in European States Show the Weaknesses of Nation-States. Medium. https://medium.com/freeman-spogli-institute-for-international-studies/anti-virus-measures-in-european-states-show-the-weaknesses-of-nation-states-101d21c0fac2

-

-

science.sciencemag.org science.sciencemag.org

-

Thorp, H. H. (2020). Underpromise, overdeliver. Science, 367(6485), 1405–1405. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8492

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

Davies, R. (2020, July 16). Number of UK problem gamblers seeking help soars in lockdown. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jul/16/lockdown-sparked-huge-upsurge-in-uk-problem-gamblers-seeking-help

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

ReconfigBehSci on Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved 5 March 2021, from https://twitter.com/SciBeh/status/1325729757447794688

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

ReconfigBehSci. (2021, January 14). RT @jimtankersley: The Biden ‘American Rescue Plan’ goes big: $1.9T, incl almost every Dem stimulus priority under the sun: State/local… [Tweet]. @SciBeh. https://twitter.com/SciBeh/status/1349993219988328449

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

Tankersley, J., & Crowley, M. (2021, January 14). Biden Outlines $1.9 Trillion Spending Package to Combat Virus and Downturn. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/14/business/economy/biden-economy.html

-

-

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

-

Fitzpatrick, M. (2006). The Cutter Incident: How America’s First Polio Vaccine Led to a Growing Vaccine Crisis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99(3), 156.

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Lakens, D., Tunç, D. U., & Tunç, M. N. (2021). There is no generalizability crisis. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/tm8jy

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

the Guardian. ‘Unicef to Feed Hungry Children in UK for First Time in 70-Year History’, 16 December 2020. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/dec/16/unicef-feed-hungry-children-uk-first-time-history.

-

-

-

Wolf, Martin. ‘Ten Ways Coronavirus Crisis Will Shape World in Long Term’, 3 November 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/9b0318d3-8e5b-4293-ad50-c5250e894b07.

-

-

-

To end covid-19, we must end discrimination and inequality. (2021, March 1). The BMJ. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/03/01/to-end-covid-19-we-must-end-discrimination-and-inequality/

Tags

- health policy

- goal

- sustainable development

- discrimination

- COVID-19

- vulnerable

- crisis

- country

- global health

- law

- healthcare

- is:article

- inequality

- public policy

- policy

- lang:en

- pandemic

- government

- pledge

- global

- reduction

- community

- health

- global population

- human development

- public health

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.edelman.com www.edelman.com

-

2021 Edelman Trust Barometer. (n.d.). Edelman. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.edelman.com/trust/2021-trust-barometer

-

-

-

Quick summaries of SciBeh Virtual Workshop Day 1. (n.d.). HackMD. Retrieved March 7, 2021, from https://hackmd.io/@scibeh/SkyuLWvtw#Session-1-Open-Science-and-Crisis-Knowledge-Management

-

-

www.activepapers.org www.activepapers.org

-

There are currently three implementations of the ActivePapers concept: the Python edition, the JVM edition, and the Pharo edition

There is only one reasonable approach, and it's not even mentioned as an option here: the browser edition. (I.e., written to target the ubiquitous WHATWG/W3C hypertext system.)

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Sci Beh. (2020, November 19). SciBeh Workshop Day 1 Session 1: Open Science and Crisis Knowledge Management. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31KBbnqNJi0

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

dawnlxh. (2020, October 30). Ideas for discussion: what is the role of open science is crisis knowledge management? [Reddit Post]. R/BehSciAsk. https://www.reddit.com/r/BehSciAsk/comments/jkzooc/ideas_for_discussion_what_is_the_role_of_open/gbtktep/

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

ReconfigBehSci. (2020, November 9). final speaker in our ‘Open science and crisis knowledge management’ session: Michele Starnini on radically redesigning the peer review system #scibeh2020 https://t.co/Gsr66BRGcJ [Tweet]. @SciBeh. https://twitter.com/SciBeh/status/1325734449783443461

-

-

oii.zoom.us oii.zoom.us

-

Welcome! You are invited to join a webinar: ‘Understanding Digital Racism After COVID-19’ with Professor Lisa Nakamura. After registering, you will receive a confirmation email about joining the webinar. (n.d.). Zoom Video. Retrieved 6 March 2021, from https://oii.zoom.us/webinar/register/2216016571338/WN_TrfmBBp-Rrm_ASHWL5e6nA

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

ReconfigBehSci on Twitter: ‘Session 1: “Open Science and Crisis Knowledge Management now underway with Chiara Varazzani from the OECD” How can we adapt tools, policies, and strategies for open science to provide what is needed for policy response to COVID-19? #scibeh2020’ / Twitter. (n.d.). Retrieved 5 March 2021, from https://twitter.com/SciBeh/status/1325720293965443072

-

-

blog.metrolinx.com blog.metrolinx.com

-

metrolinx. (2020, November 19). How COVID has impacted transit – Metrolinx releases ridership map covering all GO Transit rail routes. Metrolinx News. https://blog.metrolinx.com/2020/11/19/how-covid-has-impacted-transit-metrolinx-releases-ridership-map-covering-all-go-transit-rail-routes/

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Dante Licona. (2020, December 8). What can NGOs, government and public institutions do on TikTok? Today @melisfiganmese and I shared some insights at #EuroPCom, the @EU_CoR conference for public communication. We were asked to talk about upcoming social media trends. Here’s a thread with some insights👇 https://t.co/GzOA66vstQ [Tweet]. @Dante_Licona. https://twitter.com/Dante_Licona/status/1336303773334069251

-

- Feb 2021

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

Chwalisz, C. (2021). The pandemic has pushed citizen panels online. Nature, 589(7841), 171–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00046-7

-

-

www.cbc.ca www.cbc.ca

-

Pennycook, Gordon. ‘How the COVID-19 Crisis Exposes Widespread Climate Change Hypocrisy’. CBC, 22 May 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/opinion-climate-change-should-believe-dont-understand-1.5482416.

-

-

www.thelancet.com www.thelancet.com

-

Horton, Richard. ‘Offline: COVID-19—a Crisis of Power’. The Lancet 396, no. 10260 (31 October 2020): 1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32262-5.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Dr Phil Hammond 💙. (2020, December 6). In some parts of the country, 31% of care home staff come from the EU. Some areas already have a 26% vacancy rate. And on January 1, EU recruitment will plummet because workers earn less than the £26,500 threshold. A very predictable recruitment crisis on top of the Covid crisis. [Tweet]. @drphilhammond. https://twitter.com/drphilhammond/status/1335490431837200384

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Johnson, M. S., Skjerdingstad, N., Ebrahimi, O. V., Hoffart, A., & Johnson, S. U. (2020). Mechanisms of Parental Stress During and After the COVID-19 Lockdown: A two-wave longitudinal study. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/76pgw

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Haslam, S. A., Steffens, N. K., Reicher, S., & Bentley, S. (2020). Identity leadership in a crisis: A 5R framework for learning from responses to COVID-19. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bhj49

-

-

www.scientificamerican.com www.scientificamerican.com

-

Stix, Y. Z., Gary. (n.d.). COVID Is on Track to Become the U.S.’s Leading Cause of Death—Yet Again. Scientific American. Retrieved 22 February 2021, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/covid-is-on-track-to-become-the-u-s-s-leading-cause-of-death-yet-again1/

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

Covid eruption in Brazil’s largest state leaves health workers begging for help. (2021, January 14). The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/14/brazil-manaus-amazonas-covid-coronavirus

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Psederska, E., Vasilev, G., DeAngelis, B., Bozgunov, K., Nedelchev, D., Vassileva, J., & al’Absi, M. (2021). Resilience, mood, and mental health outcomes during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Bulgaria. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8nraq

-

- Jan 2021

-

profstevekeen.medium.com profstevekeen.medium.com

-

These predictions are absurd. A 3°C increase could trigger, and a6°C increase would trigger, every “tipping element” shown in Table 2. The Earth would have a climate unlike anything our species has experienced in its existence, and the Earth would transition to it hundreds of times faster than it has in any previous naturally-driven global warming event (McNeall et al., 2011). The Tropics and much of the globe’s temperate zone would be uninhabitable by humans and most other life forms. And yet Nordhaus thinks it would only reduce the global economy by just 8%?Comically, Nordhaus’s damage function is symmetrical — it predicts the same damages from a fall in temperature as for an equivalent rise. It therefore predicts that a 6°C fall in global temperature would also reduce GGP by just 7.9% (see Figure 3). Unlike global warming, we do know what the world was like when the temperature was 6°C below 20th century levels: that was the average temperature of the planet during the last Ice Age (Tierney et al., 2020), which ended about 20,000 years ago. At the time, all of America north of New York, and of Europe north of Berlin, was beneath a kilometre of ice. The thought that a transition to such a climate in just over a century would cause global production to fall by less than 8% is laughable.Again, I found myself in the position of a forensic detective, trying to work out how on Earth could otherwise intelligent people come to believe that climate change would only affect industries that are directly exposed to the weather, and that the correlation between climate today and economic output today across the globe could be used to predict the impact of global warming on the economy? The only explanation that made sense is that these economists were mistaking the weather for the climate.

Wow!

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Suthaharan, P., Reed, E., Leptourgos, P., Kenney, J., Uddenberg, S., Mathys, C., Litman, L., Robinson, J., Moss, A., Taylor, J., Groman, S., & Corlett, P. R. (2020). Paranoia and Belief Updating During a Crisis. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mtces

-

-

reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk

-

As vaccines start rolling out, here’s what our research says about communication and coronavirus. (n.d.). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved 13 January 2021, from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/risj-review/vaccines-start-rolling-out-heres-what-our-research-says-about-communication-and

-

-

www.buzzfeednews.com www.buzzfeednews.com

-

The insurrection isn’t just being televised. It’s being orchestrated, promoted, and broadcast on the platforms of companies with a collective value in the trillions of dollars.

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

If human beings really were able to take the long view — to consider seriously the fate of civilization decades or centuries after our deaths — we would be forced to grapple with the transience of all we know and love in the great sweep of time. So we have trained ourselves, whether culturally or evolutionarily, to obsess over the present, worry about the medium term and cast the long term out of our minds, as we might spit out a poison.

+10

-

These theories share a common principle: that human beings, whether in global organizations, democracies, industries, political parties or as individuals, are incapable of sacrificing present convenience to forestall a penalty imposed on future generations. When I asked John Sununu about his part in this history — whether he considered himself personally responsible for killing the best chance at an effective global-warming treaty — his response echoed Meyer-Abich. “It couldn’t have happened,” he told me, “because, frankly, the leaders in the world at that time were at a stage where they were all looking how to seem like they were supporting the policy without having to make hard commitments that would cost their nations serious resources.” He added, “Frankly, that’s about where we are today.”

-

- Dec 2020

-

www.amazon.co.uk www.amazon.co.uk

-

It seems to also highlight how much our governments, banks and big corporations roles play into the state of our planet, how much we need them to change so that our individual choices can actually make a significant difference. Read more

Notice the subtle othering: it's not "us" who have been doing this but the "governments, banks and big corporations" ... But who are their shareholders, who are their citizens, staff, customers etc? Us ...

Note this is a comment on Attenborough's book. I do wonder what his recommendations are...

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Hu, C., Zhu, K., Huang, K., Yu, B., Jiang, W., Peng, K., & Wang, F. (2020, November 30). Using Natural Intervention to Promote Subjective Well-being of COVID-19 Essential Workers. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mc57s

-

- Nov 2020

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Zhang, Y., & Cook, C. (2020). A Rapid Scoping Review of Publications Examining Psychological Impacts of COVID-19 in China. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/2uadr

-

-

-

Business, A. T., CNN. (n.d.). The economy as we knew it might be over, Fed Chairman says. CNN. Retrieved 18 November 2020, from https://www.cnn.com/2020/11/12/economy/economy-after-covid-powell/index.html

-

- Oct 2020

-

www.thelocal.se www.thelocal.se

-

What you need to know about Sweden’s new local coronavirus recommendations. (2020, October 19). https://www.thelocal.se/20201019/what-you-need-to-know-about-swedens-new-local-coronavirus-recommendations

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

APPG on Coronavirus on Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved October 27, 2020, from https://twitter.com/AppgCoronavirus/status/1318471895914893313

-

-

www.independentsage.org www.independentsage.org

-

The Independent SAGE Report 18. Retrieved from https://www.independentsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Emergency-plan-Oct-2020-FINAL.pdf on 25/10/2020

-

-

www.thelancet.com www.thelancet.com

-

Health, T. L. P. (2020). COVID-19 in Spain: A predictable storm? The Lancet Public Health, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30239-5

-

-

www.idsociety.org www.idsociety.org

-

“Herd Immunity” is Not an Answer to a Pandemic. (n.d.). Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://www.idsociety.org/news--publications-new/articles/2020/herd-immunity-is-not-an-answer-to-a-pandemic/

-

-

www.coe.int www.coe.int

-

AI and control of Covid-19 coronavirus. (n.d.). Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://www.coe.int/en/web/artificial-intelligence/ai-and-control-of-covid-19-coronavirus

-

-

www.thelancet.com www.thelancet.com

-

Alter, S. M., Maki, D. G., LeBlang, S., Shih, R. D., & Hennekens, C. H. (2020). The menacing assaults on science, FDA, CDC, and health of the US public. EClinicalMedicine, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100581

-

-

www.scientificamerican.com www.scientificamerican.com

-

Jackson, A. S., Ingrid Joylyn Paredes,Tiara Ahmad,Christopher. (n.d.). Yes, Science Is Political. Scientific American. Retrieved October 13, 2020, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/yes-science-is-political/

-

-

blogs.bmj.com blogs.bmj.com

-

Abraar Karan: Politics and public health in America—taking a stand for what is right. (2020, October 9). The BMJ. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/10/09/abraar-karan-politics-and-public-health-in-america-taking-a-stand-for-what-is-right/

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

Yong, S. by E. (n.d.). America Is Trapped in a Pandemic Spiral. The Atlantic. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/09/pandemic-intuition-nightmare-spiral-winter/616204/

-

-

adactio.com adactio.com

-

Summary of Margot Bloomstein's talk "Designing for Trust in an uncertain world." (Recording of a similar talk on Vimeo)

-

Mass media and our most cynical memes say we live in a post-fact era. So who can we trust — and how do our users invest their trust?

Margot's starting point is what has been called the epistemic crisis.

-

-

covid-19.iza.org covid-19.iza.org

-

COVID-19 and the Labor Market. (n.d.). IZA – Institute of Labor Economics. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from https://covid-19.iza.org/publications/dp13760/

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Adam Kucharski on Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://twitter.com/AdamJKucharski/status/1313760847932596224

-

-

www.psychologs.com www.psychologs.com

-

Covid-19: Is Behavioural Science The Key To Handle The Pandemic? (n.d.). Retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://www.psychologs.com/article/covid-19-is-behavioral-science-the-key-to-handle-the-pandemic

-

-

www.propublica.org www.propublica.org

-

The places migrants left behind never fully recovered. Eighty years later, Dust Bowl towns still have slower economic growth and lower per capita income than the rest of the country. Dust Bowl survivors and their children are less likely to go to college and more likely to live in poverty. Climatic change made them poor, and it has kept them poor ever since.

Intergenerational social problems here; we should be able to learn from the past and not repeat our mistakes.

-

Part of the problem is that most policies look only 12 months into the future, ignoring long-term trends even as insurance availability influences development and drives people’s long-term decision-making.

Another place where markets are failing us. We need better regulation for this sort of behavior.

-

-

www.npr.org www.npr.org

-

Miya Yoshitani, executive director of the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, which focuses on environmental justice issues affecting working-class Asian and Pacific Islander immigrant and refugee communities.

-

There's a grassy vacant lot near her apartment where Franklin often takes a break from her job as a landscaping crew supervisor at Bon Secours Community Works, a nearby community organization owned by Bon Secours Health System. It's one of the few places in the neighborhood with a lot of shade — mainly from a large tree Franklin calls the mother shade. She helped come up with the idea to build a free splash park in the lot for residents to cool down in the heat. Now Bon Secours is taking on the project. "This was me taking my stand," Franklin says. "I didn't sit around and wait for everybody to say, 'Well, who's going to redo the park?' "

Reminiscent of the story in Judith Rodin's The Resilience Dividend about the Kambi Moto neighborhood in the Huruma slum of Nairobi. The area and some of the responsibility became a part of ownership of the space from the government. Meanwhile NPR's story here is doing some of the counting which parallels the Kambi Moto story.

-

-

psmag.com psmag.com

-

Consumer demand is one of four important variables that, when combined, can influence and shape farming practices, according to Festa. The other three are the culture of farming communities, governmental policies, and the economic system that drives farming.

-

Festa argues that this is why organic farming in the U.S. saw a 56 percent increase between 2011 and 2016.

A useful statistic but it needs more context. What is the percentage of organic farming to the overall total of farming?

Fortunately the linked article provides some additional data: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/10/organic-farming-is-on-the-rise-in-the-u-s/

-

"The fundamental problem with climate change is that it's a collective problem, but it rises out of lots of individual decisions. Society's challenge is to figure out how we can influence those decisions in a way that generates a more positive collective outcome," says Keith Wiebe, senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute.

-

Agriculture, forestry, and other types of land use account for 23 percent of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, according to the IPCC.

-

-

www.pewresearch.org www.pewresearch.org

-

Still, organic farming makes up a small share of U.S. farmland overall. There were 5 million certified organic acres of farmland in 2016, representing less than 1% of the 911 million acres of total farmland nationwide. Some states, however, had relatively large shares of organic farmland. Vermont’s 134,000 certified organic acres accounted for 11% of its total 1.25 million farm acres. California, Maine and New York followed in largest shares of organic acreage – in each, certified organic acres made up 4% of total farmland.

-

-

drive.google.com drive.google.com

-

climate theorists

I find it interesting to be reading about a completely different sort of climate theory in this book than the one commonly known in popular society.

-

-

apps.who.int apps.who.int

-

Pandemic fatigue – reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19. Policy framework for supporting pandemic prevention and management. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

-

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

Bingham, K. (2020). Plan now to speed vaccine supply for future pandemics. Nature, 586(7828), 171–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02798-0

-

-

socialsciences.nature.com socialsciences.nature.com

-

Bericht über die Studie zum Verhältnis von Klimabildung und Ideologie. Verweise zu den wichtigsten Forschungen in dieser Richtung

-

-

covid-19.iza.org covid-19.iza.org

-

IZA – Institute of Labor Economics. ‘COVID-19 and the Labor Market’. Accessed 6 October 2020. https://covid-19.iza.org/publications/dp13742/.

-

-

covid-19.iza.org covid-19.iza.org

-

IZA – Institute of Labor Economics. ‘COVID-19 and the Labor Market’. Accessed 6 October 2020. https://covid-19.iza.org/publications/dp13720/.

-

-

www.deutschlandfunk.de www.deutschlandfunk.de

-

Ausführliche Sendung über Desinformationstechniken vor allem im Umkreis der Trump-Kampagne, viele Hinweise auf weitere Ressourcen

-

- Sep 2020

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Learning lessons before launching an inquiry—IfG LIVE 2020 Labour Fringe Programme—YouTube. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCZl-naQ6UM

-

-

www.huffpost.com www.huffpost.com

-

HuffPost UK. ‘The Coronavirus Is Creating A Mental Health Crisis For Health Care Workers’, 21 September 2020. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/health-care-workers-covid-mental-health_n_5f625a6ac5b6c6317cfed815.

-

-

gerriteicker.de gerriteicker.de

-

die Werkzeuge verstanden und genutzt werden, die der Menschheit durch ihre gesamte Geschichte zur Verfügung standen

Ich will deine Analyse auf gar keinen Fall besserwisserisch kritisieren. Ich kann alle Aussagen unterschreiben, und ich habe Grund, an meinen eigenen Kategorien und an meiner politischen und sozialen Analysefähigkeit zu zweifeln. Meine Einwände—eher Vorschläge, weiter zu gehen—sind:

- Klammerst du nicht Machtfragen aus, die für die epistemic crisis, von der du ausgehst entscheidend sind? Hinter Trump, dem Brexit und der Propaganda für sie stehen Interessengruppen und Individuen, wie die Koch-Brüder und Rupert Murdoch.

- Sind Aufklärung, Wissen und Technologie einheitliche Phänomene, oder gehören sie nicht zu sehr unterschiedlichen konkreten Konstellationen? Kann man nicht z.B. daran zweifeln, dass die Entwicklung der sozialen Medien tatsächlich im Sinne der Aufklärung verlief? Sollte man nicht eher konkrete working anarchies, demokratische Formen der Kooperation wie in den Wissenschaften oder im offenen Netz verteidigen statt abstrakt für Rationalität und Aufklärung als solche einzutreten?

- Sind die ökologischen Krisen, die great acceleration und die globale Ungerechtigkeit nicht auch Ursachen für die epistemic crisis? Betreibt etwas Trump oder die Gruppe, deren Interessen er vertritt, nicht vielleicht deshalb eine wissenschaftsfeindliche Politik, weil wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse klar zeigen, dass diese Machtgruppen die Menschheit in eine Existenzgruppe führen?

Zusammengefasst ich würde Aufklärung und Wissenschaft als etwas Lokaleres und Bestimmteres verstehen, verbunden mit Interessen und politischen Strukturen, und ich sehe die epistemische Krise als Komponente von Machtkämpfen—Machtkämpfen zwischen den Eliten, aber auch zwischen Eliten und den Interessen anderer Gruppen. Ich will damit aber nicht umgekehrt eine Fragmentierung von Vernunft und Aufklärung betreiben, sondern nur ihre Sozialisierung durch Einbettung in kooperative Strukturen.

-

Netzpolitik, Digitalpolitik, Wissenspolitik können sich diesen fatalen Entwicklungen entgegenstellen. Die Politikfelder eröffnen zumindest einen argumentativen und institutionellen Rahmen, innerhalb dessen gedacht, gestritten und entschieden werden kann.

Du schreibst jetzt über drei miteinander verbundene Politikfelder. Aber stellt nicht die Entwicklung, von der du ausgehst, den Politikansatz in Frage, in dem sich solche Themenpolitiken betreiben lassen? Und zeigt die Aufteilung in Netz-, Digital- und Wissenspolitik nicht vielleicht auch, dass die Digitalisierung nicht das einheitliche Phänomen ist, als das sie uns erscheint?

-

Parallel wird das Internet immer weiter in kleinere Netze aufgespalten

Hier berührst du auch das Thema der Globalisierung, das man wahrscheinlich nicht von denen der epistemischen Krise und des Digitalen abtrennen kann. - Ist diese Verbindung der Themen nicht ein Indiz dafür, dass es immer zugleich um wirtschaftliche Interessen und um Macht geht? Hypothetisch formuliert: Haben wir es hier nicht mit Koalitionen von antiglobalistischen Eliten und Teilen der Bevölkerung zu tun, die sich durch die weitere Modernisierung bedroht fühlen?

-

Statt, dank dem jederzeit möglichen Zugriff auf relevante Informationen und Wissen, gut informiert nachhaltige Entscheidungen zu treffen, werden Fakten schlicht abgeleugnet, sogar gegen ein Virus demonstriert oder gleich 5G-Masten abgefackelt?

Du verstehst diese epistemische Krise als Gegensatz zwischen einem im weitesten Sinn aufkärerischem Herangehen an gesellschaftliche Probleme und einem irrationalistischen, faktenfeindlichen Vorgehen. Wenn ich es richtig sehe, dann argumentierst du im weiteren Verlauf des Textes dafür, mit noch mehr Aufklärung zu reagieren, und differenzierst innerhalb des aufklärerischen Ansatzes zwischen Netz-, Digital- und Wissenspolitik.

-

Ich würde das, was du hier diagnostizierst, als Epistemic Crisis bezeichnen. Ich nehme sie genauso wahr wie du, und ich bin auch darüber entsetzt. Das erste Warnsignal, das ich ernst genommen habe, war der Brexit, das zweite die Wahl von Trump. Beide habe ich vorher nicht erwartet, weil sie jenseits des Horizonts waren, in dem ich Entwicklungen erwartet habe. ich muss also auch an der Art und Weise zweifeln, in der ich politische Entwicklungen verstanden habe.—Später kam dann für mich der Aufstieg der Freiheitlichen hier in Österreich, bis hin zur Regierungsbeteiligung, und die rechtspopulistische Welle (wenn man es so nennen will) in Frankreich und Italien.

-

-

www.scientificamerican.com www.scientificamerican.com

-

Hotz, J. (n.d.). Can an Algorithm Help Solve Political Paralysis? Scientific American. Retrieved September 21, 2020, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-an-algorithm-help-solve-political-paralysis/

-

-

today.law.harvard.edu today.law.harvard.edu

-

Kunycky, A., September 16, & 2020. (n.d.). ‘Every drop in the ocean counts.’ Harvard Law Today. Retrieved September 21, 2020, from https://today.law.harvard.edu/every-drop-in-the-ocean-counts/

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Webinar series DAY 1 - Insights into COVID-19 modelling & evidence-based policy making. Retrieved from on 21/09/2020 from https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLNzrUckV9eSJAybOPMPxPulI0bciy8HXf

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Webinar series DAY 2 - Insights into COVID-19 modelling & evidence-based policy making. Retrieved on 21/09/2020 from https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLNzrUckV9eSJIF41YCUaUWHOg_CTxmc99

-

-

www.rsm.ac.uk www.rsm.ac.uk

-

Covid-19: Herd immunity in Sweden fails to materialise | The Royal Society of Medicine. (n.d.). Retrieved September 18, 2020, from https://www.rsm.ac.uk/media-releases/2020/covid-19-herd-immunity-in-sweden-fails-to-materialise/

-

-

www.medrxiv.org www.medrxiv.org

-

Gardner, J. M., Willem, L., Wijngaart, W. van der, Kamerlin, S. C. L., Brusselaers, N., & Kasson, P. (2020). Intervention strategies against COVID-19 and their estimated impact on Swedish healthcare capacity. MedRxiv, 2020.04.11.20062133. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.11.20062133

-

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

Lincoln, M. (2020). Study the role of hubris in nations’ COVID-19 response. Nature, 585(7825), 325–325. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02596-8

-

-

www.bloomberg.com www.bloomberg.com

-

It’s Hard to Keep a College Safe From Covid, Even With Mass Testing. (2020, September 11). Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-11/how-coronavirus-rampaged-through-university-of-illinois-college-campus

Tags

- is:news

- strategy

- safety measure

- crisis management

- USA

- reopening

- higher education

- closure

- case increase

- lang:en

- COVID-19

- testing

- university

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.propublica.org www.propublica.org

-

Keenan calls the practice of drawing arbitrary lending boundaries around areas of perceived environmental risk “bluelining,” and indeed many of the neighborhoods that banks are bluelining are the same as the ones that were hit by the racist redlining practice in days past. This summer, climate-data analysts at the First Street Foundation released maps showing that 70% more buildings in the United States were vulnerable to flood risk than previously thought; most of the underestimated risk was in low-income neighborhoods.

Bluelining--a neologism I've not seen before, but it's roughly what one would expect.

-

Jesse Keenan, an urban-planning and climate-change specialist then at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, who advises the federal Commodity Futures Trading Commission on market hazards from climate change. Keenan, who is now an associate professor of real estate at Tulane University’s School of Architecture, had been in the news last year for projecting where people might move to — suggesting that Duluth, Minnesota, for instance, should brace for a coming real estate boom as climate migrants move north.

Why can't we project additional places like this and begin investing in infrastructure and growth in those places?

-

That’s what happened in Florida. Hurricane Andrew reduced parts of cities to landfill and cost insurers nearly $16 billion in payouts. Many insurance companies, recognizing the likelihood that it would happen again, declined to renew policies and left the state. So the Florida Legislature created a state-run company to insure properties itself, preventing both an exodus and an economic collapse by essentially pretending that the climate vulnerabilities didn’t exist.

This is an interesting and telling example.

-

And federal agriculture aid withholds subsidies from farmers who switch to drought-resistant crops, while paying growers to replant the same ones that failed.

Here's a place were those who cry capitalism will save us should be shouting the loudest!

-

The federal National Flood Insurance Program has paid to rebuild houses that have flooded six times over in the same spot.

We definitely need to quit putting good money after bad.

-

Similar patterns are evident across the country. Census data shows us how Americans move: toward heat, toward coastlines, toward drought, regardless of evidence of increasing storms and flooding and other disasters.

And we wonder why there are climate deniers in the United States?

-

-

journals.sagepub.com journals.sagepub.com

-

Spellman, B. A. (2015). A Short (Personal) Future History of Revolution 2.0. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), 886–899. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615609918

-

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

Coronavirus cases are rising again in the UK. Here’s what should happen next | Devi Sridhar. (2020, September 8). The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/08/coronavirus-cases-rising-uk-second-wave

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Jason Furman on Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved September 7, 2020, from https://twitter.com/jasonfurman/status/1301871401226338305

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Lee, Hyeon-seung, Derek Dean, Tatiana Baxter, Taylor Griffith, and Sohee Park. ‘Deterioration of Mental Health despite Successful Control of the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea’. Preprint. PsyArXiv, 30 August 2020. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/s7qj8.

Tags

- social distancing

- general population

- COVID-19

- nationwide lockdown

- crisis

- loneliness

- depression

- anxiety

- behavioural science

- psychosis-risk

- South Korea

- females

- social factors

- lang:en

- physical health

- stress

- social network

- mental health

- is:preprint

- demographic

- public health

- psychological outcome

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.pmo.gov.sg www.pmo.gov.sg

-

katherine_chen. (2020, June 17). PMO | National Broadcast by PM Lee Hsien Loong on 7 June 2020 [Text]. Prime Minister’s Office Singapore; katherine_chen. http://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/National-Broadcast-PM-Lee-Hsien-Loong-COVID-19

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Van Bavel, J. J., & Myer, A. (2020). National identity predicts public health support during a global pandemic [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ydt95

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Sir Anthony Seldon on Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved September 2, 2020, from https://twitter.com/AnthonySeldon/status/1300355492783554561

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Hanna Rosin of The Atlantic argues that prosperity theology contributed to the housing bubble that caused the late-2000s financial crisis. She maintains that prosperity churches heavily emphasized home ownership based on reliance on divine financial intervention that led to unwise choices based on actual financial ability.[36]

This is a fascinating theory. I wonder how well it plays out for evidence?

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Rodriguez, C. G., Gadarian, S. K., Goodman, S. W., & Pepinsky, T. (2020). Morbid Polarization: Exposure to COVID-19 and Partisan Disagreement about Pandemic Response [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/wvyr7

-

- Aug 2020

-

-

Harford, Tim. ‘A Bluffer’s Guide to Surviving Covid-19 | Free to Read’, 28 August 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/176b9bbe-56cf-4428-a0cd-070db2d8e6ff.

-

-

www.npr.org www.npr.org

-

Day Care, Grandparent, Pod Or Nanny? How To Manage The Risks Of Pandemic Child Care. (n.d.). NPR.Org. Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/08/21/902613282/daycare-grandparent-pod-or-nanny-how-to-manage-the-risks-of-pandemic-child-care

-

-

www.washingtonpost.com www.washingtonpost.com

-

Yu, X. (n.d.). Opinion | I’m from Wuhan. I got covid-19—After traveling to Florida. Washington Post. Retrieved 17 July 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/07/15/im-wuhan-i-got-covid-19-after-traveling-florida/

-

-

www.thelancet.com www.thelancet.com

-

Heywood, A. E., & Macintyre, C. R. (2020). Elimination of COVID-19: What would it look like and is it possible? The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30633-2

-

-

osf.io osf.io

-

Enriquez, D., & Goldstein, A. (2020). Covid-19’s Socio-Economic Impact on Low-Income Benefit Recipients: Early Evidence from Tracking Surveys [Preprint]. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hpqd5

-

-

journals.plos.org journals.plos.org

-

Aiken, E. L., McGough, S. F., Majumder, M. S., Wachtel, G., Nguyen, A. T., Viboud, C., & Santillana, M. (2020). Real-time estimation of disease activity in emerging outbreaks using internet search information. PLOS Computational Biology, 16(8), e1008117. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008117

-

-

www.siliconrepublic.com www.siliconrepublic.com

-

Gorey, C. (2020, June 29). RCSI team to start trial for promising Covid-19 therapy for severe infections. Silicon Republic. https://www.siliconrepublic.com/innovation/rcsi-trial-covid-19-therapy-alpha-1-antitrypsin

-

-

onlinelibrary.wiley.com onlinelibrary.wiley.com

-

Frias‐Navarro, D., Pascual‐Llobell, J., Pascual‐Soler, M., Perezgonzalez, J., & Berrios‐Riquelme, J. (n.d.). Replication crisis or an opportunity to improve scientific production? European Journal of Education, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12417

-

-

www.bbc.co.uk www.bbc.co.uk

-

BBC Sounds. (2020, April 16. The Briefing Room—The psychological impact of the coronavirus pandemic. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000h7sp

-

-

royalsocietypublishing.org royalsocietypublishing.org

-

Stutt, R. O. J. H., Retkute, R., Bradley, M., Gilligan, C. A., & Colvin, J. (2020). A modelling framework to assess the likely effectiveness of facemasks in combination with ‘lock-down’ in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 476(2238), 20200376. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2020.0376

-

-

www.scientificamerican.com www.scientificamerican.com

-

Barber, C. (n.d.). ‘Instant Coffee’ COVID-19 Tests Could Be the Answer to Reopening the U.S. Scientific American. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/instant-coffee-covid-19-tests-could-be-the-answer-to-reopening-the-u-s/

-

-

csbs.research.illinois.edu csbs.research.illinois.edu

-

What We Know About College Students to Help Manage COVID-19 – Center for Social & Behavioral Science. (n.d.). Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://csbs.research.illinois.edu/2020/08/16/what-we-know-about-college-students-to-help-manage-covid-19/

-

-

osf.io osf.io

-

Nelson, N. C., Ichikawa, K., Chung, J., & Malik, M. (2020). Mapping the discursive dimensions of the reproducibility crisis: A mixed methods analysis [Preprint]. MetaArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/sbv3q

-

-

-

Althouse, B. M., Wallace, B., Case, B., Scarpino, S. V., Berdahl, A. M., White, E. R., & Hebert-Dufresne, L. (2020). The unintended consequences of inconsistent pandemic control policies. ArXiv:2008.09629 [Physics, q-Bio]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2008.09629

-

-

www.latimes.com www.latimes.com

-

C. L., & Print. (2020, August 14). Op-Ed: We rely on science. Why is it letting us down when we need it most? Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-08-14/replication-crisis-science-cancer-memory-rewriting

-

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Bordo, M. D., Levin, A. T., & Levy, M. D. (2020). Incorporating Scenario Analysis into the Federal Reserve’s Policy Strategy and Communications (Working Paper No. 27369; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27369

-

-

-

Peterson, David, and Aaron Panofsky. ‘Metascience as a Scientific Social Movement’. Preprint. SocArXiv, 4 August 2020. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/4dsqa.

-

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Aizenman, Joshua, Yothin Jinjarak, Donghyun Park, and Huanhuan Zheng. ‘Good-Bye Original Sin, Hello Risk On-Off, Financial Fragility, and Crises?’ National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, 23 April 2020. https://www.nber.org/papers/w27030.

-

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Correa, R., Du, W., & Liao, G. Y. (2020). U.S. Banks and Global Liquidity (Working Paper No. 27491; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27491

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Esther Choo, MD MPH on Twitter: “Question for Twitter. Why didn’t academia take the lead on Covid information? Why didn’t schools of med & public health across the US band together, put forth their experienced scientists in epidemiology, virology, emergency & critical care, pandemic and disaster response...” / Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved August 10, 2020, from https://twitter.com/choo_ek/status/1291789978716868608

-

-

www.medrxiv.org www.medrxiv.org

-

Aguas, R., Corder, R. M., King, J. G., Goncalves, G., Ferreira, M. U., & Gomes, M. G. M. (2020). Herd immunity thresholds for SARS-CoV-2 estimated from unfolding epidemics. MedRxiv, 2020.07.23.20160762. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.20160762

-

-

covid-19.iza.org covid-19.iza.org

-

Immigrant Key Workers: Their Contribution to Europe’s COVID-19 Response. COVID-19 and the Labor Market. (n.d.). IZA – Institute of Labor Economics. Retrieved August 7, 2020, from https://covid-19.iza.org/publications/dp13178/

-

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Falato, A., Goldstein, I., & Hortaçsu, A. (2020). Financial Fragility in the COVID-19 Crisis: The Case of Investment Funds in Corporate Bond Markets (Working Paper No. 27559; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27559

-

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hendren, N., Stepner, M., & Team, T. O. I. (2020). How Did COVID-19 and Stabilization Policies Affect Spending and Employment? A New Real-Time Economic Tracker Based on Private Sector Data (Working Paper No. 27431; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27431

-

-

covid-19.iza.org covid-19.iza.org

-

Reacting Quickly and Protecting Jobs: The Short-Term Impacts of the COVID-19 Lockdown on the Greek Labor Market. COVID-19 and the Labor Market. (n.d.). IZA – Institute of Labor Economics. Retrieved July 27, 2020, from https://covid-19.iza.org/publications/dp13516/

-

-

www.nber.org www.nber.org

-

Sims, E. R., & Wu, J. C. (2020). Wall Street vs. Main Street QE (Working Paper No. 27295; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27295

-

-

debunkingdenialism.com debunkingdenialism.com

-

Sweden Did Not Take Herd Immunity Approach Against Coronavirus Pandemic. (2020, July 29). Debunking Denialism. https://debunkingdenialism.com/2020/07/29/sweden-did-not-take-herd-immunity-approach-against-coronavirus-pandemic/

-

-

-

Akbarpour, M., Cook, C., Marzuoli, A., Mongey, S., Nagaraj, A., Saccarola, M., Tebaldi, P., Vasserman, S., & Yang, H. (2020). Socioeconomic Network Heterogeneity and Pandemic Policy Response (Working Paper No. 27374; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27374

-

- Jul 2020

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Journalism in Crisis (2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dr41ao6tKVw&feature=emb_title

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Eric Topol on Twitter: “It’s 100+ years later and we’re a lot smarter, more capable. Why aren’t we beating the crap out of #SARSCoV2? We will. Just a matter of time. https://t.co/eFGieP4cos” / Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://twitter.com/EricTopol/status/1287461741236875264

-